Kohat District, 1908

Contents |

Kohat District, 1908

Central District of the North-West Frontier Province, lying between 32 degree 48' and 33 degree 45' N. and 70 degree 30' and 72 degree 1' E; with an area of 2,973 square miles. The District has the shape of an irregular rhomboid, with one arm stretching north-east towards the Khwarra-Zira forest in Peshawar District. It is bounded on the north by Peshawar District, and by the hills inhabited by the Jowaki and Pass Afrldis ; on the north-west by Orakzai Tirah ; on the south- west by Kabul Khel territory (Wazlristan) ; on the south-east by Bannu and the Mianwali District of the Punjab ; and on the east by the Indus. Its greatest length is 104 miles, and its greatest width 50 miles.

Physical aspects

The District consists of a succession of ranges of broken hills, whose general trend is east and west, and between which lie open valleys, seldom more than 4 or 5 miles in width. These ranges are of no great height, though several peaks asDects attain an altitude of 4,700 or 4,900 feet. As the District is generally elevated, Hangu to the northward being 2,800 feet and Kohat, its head-quarters, 1,700 feet above sea-level, the ranges rise to only inconsiderable heights above the plain. The general slope is to the east, towards the Indus, but on the south-west the fall is towards the west into the Kurram river. The principal streams are the Kohat and Teri Tois (' streams '), both tributaries of the Indus, and the Shkalai which flows into the Kurram. The Kohat Toi rises in the Mamozai hills. It has but a small perennial flow, which disappears before it reaches the town of Kohat, but the stream reappears some miles lower down and thence flows continuously to the Indus. The Teri Toi has little or no perennial flow, and the Shkalai is also small, though perennial. The most fertile part is the Hangu tahsil, which comprises the valley of Lower and Upper Mlranzai. The rest of the District consists of ranges of hills much broken into spurs, ravines, and valleys, which are sometimes cultivated, but more often bare and sandy.

The rocks of the District belong chiefly to the Tertiary system, and consist of a series of Upper and Middle Tertiary sandstones with inliers of Nummulitic limestone. The limestones occur chiefly in the north, while sandstone is more prominent to the south. Below the Num- mulitic beds is found the most important mineral of the District, namely, salt. It occurs, with bands of gypsum and red clay, below the eocene rocks at various localities, but is found in greatest quantity at Bahadur Khel, where rock-salt is seen for a distance of about 8 miles and the thickness exposed exceeds 1,000 feet. The salt is very pure, and differs remarkably in colour from that of the Salt Range, being usually grey, while that of the latter area is red or pink. There is no definite evidence as to its age, which is usually regarded as Lower Tertiary ; but the underlying rocks are not exposed, and it has been classed with the overlying eocene on account of the apparent absence of any unconformity '.

The vegetation is composed chiefly of scrub jungle, with a secondary element of trees and shrubs. The more common plants are : Flacourtia sapida, F. sepiaria, several species of Grewia, Zizyphus mtmmitlaria, Acacia Jacquemontii, A. leucophoca, Alhagi camelorum, Crotalaria Burhia, Prosopis spicigera, several species of Tamarix, Nerium odorum, Rhazya stricta, Calotropis procera, Pei'iploca aphylla, Tecoma imdulata, Lycium europaeum, Withania coagulans, IV. somnifera, Na?inorlwps Ritchieana, Fagotu'a, Tribulus, Peganum Harmala, Calligomtm poly- gonoides, Polygonum aviculare, P. plebejum, Rumex vesicarius, Chrozo- phora plicafa, and species of Aristida, Anthistiria, Cenchrus, and Pennisetitm.

Game of all kinds is scarce : leopards are occasionally shot in the hills, and twenty years ago were quite common. There are practically no deer. Bears occasionally come down from the Samana range to Miranzai when the corn is ripe. Chikor and partridges abound in Miranzai and the Teri tahsl/, and fish are abundant in the Kurram and the Indus.

The District as a whole lies high ; and the hot season, though oppres- sive, is short, and the spring and autumn months are pleasant. The winter is very cold, and a cutting west wind, known as the ' Hangu breeze,' blows down the Miranzai valley to Kohat for weeks together. Owing to the great extremes of heat and cold pneumonia is common, but malarial fever is the chief cause of mortality.

The monsoon rains do not usually penetrate as far as Kohat, and the rainfall is very capricious. The annual fall at Kohat averages 18 inches, while the greatest fall since 1882 was 48 inches at Fort Lockhart on the Samana in 1900-T, and the least 5 inches at Kohat in 1891-2. The distribution of the rain is equally uncertain, villages within the distance of a few miles suffering, some from drought and some from floods, at the same time.

History

The first historical mention of the District occurs in the memoirs of the emperor Babar. The District was then, as now, divided between the Bangash and Khattak branches of the Pathan race, the Bangash occupying the Miranzai valley, with the western portion of Kohat proper, while the Khattaks held the remainder of the eastern territory up to the bank of the Indus. Accord- ing to tradition the Bangash were driven from Gardez in the Ghilzai country, and settled in the Kurram valley about the fourteenth century. Thence they spread eastward, over the Miranzai and Kohat region, fighting for the ground inch by inch with the Orakzai, whom they

1 Wynne, ' Trans-Indus Salt Region in the Kohat District,' Memoirs, Geological Survey oj India, vol. xi, part ii. cooped up at last in the frontier hills. The Khattaks are said to have left their native home in the Sulaiman mountains about the thirteenth century and settled in Bannu. Owing to a quarrel with the ancestors of the Bannuchis, they migrated northward two hundred years later and occupied their present domains.

Babar made a raid through the District in 1505, being attracted by a false hope of plunder, and sacked Kohat and Hangu. The Mughal emperors were unable to maintain more than a nominal control over the tract. One of the Khattak chiefs, Malik Akor, agreed with Akbar to protect the country south of the Kabul river from depredations, and received in return a grant of territory with the right of levying tolls at the Akora ferry. He was thus enabled to assume the chieftainship of his tribe, and to hand down his authority to his descendants, who ruled at Akora, among them being the warrior poet Khushhal Khan.

Kohat became part of the Durrani empire in 1747, but authority was exercised only through the Bangash and Khattak chiefs. Early in the nineteenth century, Kohat and Hangu formed a governorship under Sardar Samad Khan, one of the Barakzai brotherhood, whose leader, Dost Muhammad, usurped the throne of Afghanistan. The sons of Sardar Samad Khan were driven out about 1828 by the Peshawar Sardars, the principal of whom was Sultan Muhammad Khan. In the Teri tahsil, shortly after the establishment of the power of Ahmad Shah Durrani, it became the custom for a junior member of the Akora family to rule as sub-chief at Teri. This office gradually became hereditary, and sub-chiefs ruled the western Khattaks in complete independence of Akora. The history of affairs becomes very confused : the Akora chiefs were constantly interfering in Teri affairs ; there were generally two or more rival claimants ; the chiefship was constantly changing hands, and assassinations and rebellion were matters of every- day occurrence.

The Sikhs, on occupying the country, found themselves unable to levy revenue from the mountaineers. Ranjlt Singh placed Sultan Muhammad Khan in a position of importance at Peshawar, and made him a grant of Kohat, Hangu, and Teri. One Rasul Khan became chief of Teri, and on his death in 1843 was succeeded by his adopted son, Khwaja Muhammad Khan. Meanwhile, Sultan Muhammad Khan continued to govern the rest of the District through his sons, though the country was generally in a disturbed state, and the upper Miranzai villages were practically independent. When the Sikh troops took up arms at Peshawar on the outbreak of the second Sikh War, George Lawrence, the British officer there, took refuge at Kohat ; but Sultan Muhammad Khan played him false, and delivered him over as a prisoner to the Sikhs. At the close of the campaign, Sultan Muham- mad Khan and his adherents retired to Kabul, and the District with the rest of the Punjab was annexed to the British dominions. Khwaja Muhammad Khan had taken the British side and continued to manage the tahsil, which was made a perpetual jaglr. In 1872 Khwaja Mu- hammad obtained the title of Nawab and was made a K.C.S.I. He died in 1889 and was succeeded by his son, Khan Bahadur Abdul Ghafur Khan.

At annexation the western boundary was left undefined ; but in August, 185 1, Upper Miranzai was formally annexed by proclamation, and an expedition was immediately dispatched up the valley to establish our rule. There was no fighting, beyond a little skirmishing with the Wazirs near Biland Khel. The lawless Miranzai tribes, however, had no desire to be under either British or Afghan rule. They were most insubordinate, paid no revenue and obeyed no orders, while incursions from across the frontier continued to disturb the peace of the new District. At last, in 1855, a force of 4,000 men marched into the valley, enforced the revenue settlement, and punished a recusant vil- lage at the foot of the Zaimukht hills. The people of Miranzai quickly reconciled themselves to British rule; and during the Mutiny of 1857 no disturbance of any sort took place in the valley, or in any other part of the District. In March, 1858, it was finally decided that the Kurram river was to form the western boundary of the District, thus excluding the Biland Khel on the opposite bank.

The construction of the road from Kohat to Peshawar was under- taken immediately after annexation, and at once brought the British into conflict with the border tribes, while the construction of the road to Bannu by Bahadur Khel was also the occasion of outbreaks in which the salt mines were seized by the insurgents.

Population

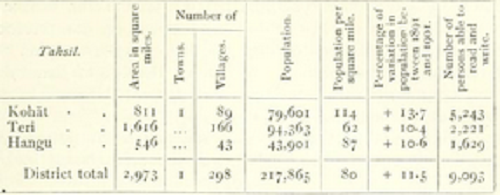

Kohat District contains one town and 298 villages. The population at the last three enumerations was: (1881) 174,762, (1891) 195,148, and (1901) 217,86 5. it increased by 11-5 per cent, during the last decade, the increase being greatest in the Kohat tahsil and least in Teri. The increase, though partly due to the presence of coolies, &c, employed in making the Khushalgarh- Kohat Railway, was mainly the result of increased tranquillity on the border. The District is divided into three tahsil, the chief statistics of which, in [901, are shown in the table on the next page.

The head-quarters of these are at the places from which each is named. The only town is Kohat, the administrative head-quarters of the District. The District also contains the military outposts of Thal and Fort Lock hart. The density of the population is low, and the population is too small in some villages to cultivate all the land. Mu- hammadans number 199,722, or more than 91 per cent, of the total; Hindus, 14,480 ; and Sikhs, 3,344. The language commonly spoken is Pashtu ; the Awans and Hindus talk Hindkl, a dialect of Punjabi, among themselves, but know Pashtu as well.

The most numerous tribe in the District are the Pathans, who num- ber 134,000, or 61 per cent, of the total population. They are divided into two main branches : the Bangash, who occupy the Miranzai valley with the western portion of the Kohat tahsil; and the Khattaks, who hold the eastern part of Kohat and the Teri tahsil up to the Indus. The Khattaks are inferior as cultivators but make better soldiers than the Bangash. Next in importance to the Pathans come the Awans (22,000), who live along the banks of the Indus and are probably im- migrants from Rawalpindi District. Saiyids number 8,000. Of the commercial and money-lending classes, the Aroras (8,000) are the most important, the Khattris numbering only 3,000, and Parachas (carriers and pedlars) 2,000. The Shaikhs, who mostly live by trade, number 3,000. Of the artisan classes, the Tarkhans (carpenters, 4,000), Lohars (blacksmiths, 4,000), and Mochls (shoemakers and leather-workers), Kumhars (potters), and Julahas (weavers), each returning 2,000, are the most important ; and of the menials, only the Nais (barbers, 3,000) and Chuhras or Kutanas (sweepers, 2,000) appear in any numerical strength. In 1901 the District contained 145 native Christians, but no mission has been established. Agriculture supports 68 per cent, of the population.

Agriculture

In the low-lying tracts along the bottom of the main valleys the soil is generally a good loam, fertile and easily worked. The silt brought down by the mountain torrents is poor and thin, but the land is as a rule well manured. In the western portion of the Hangu tahsil there are stretches of a rich dark loam, which yields good autumn crops in years of seasonable summer rains. But the predominant soil in the Dis- trict is clay, varying from a soft and easily ploughed soil to a hard one, which is useless without a great deal of water. The clay is often brick-red in colour, and this, too, is found both soft and hard. The soft red clay is an excellent soil, holding water well, and needing no manure if cropped only once a year. Towards the Indus the level land, which alone can be cultivated, has a thin sandy soil covered in many places almost entirely with stones ; these help to keep the soil cool, and without them crops could not live on the thin surface soil. Agricultural conditions, however, depend chiefly on the presence or absence of water. The spring crop, which in 1903-4 occupied 58 per cent, of the area harvested, is sown from October to January ; the autumn crop mainly in June, July, and August, though cotton and great millet are often sown in May.

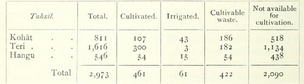

The following table shows the main statistics of cultivation accord- ing to the revenue returns for 1903-4, the areas being in square miles : —

The chief food-crops are wheat, covering 173 square miles, or 44 per cent, of the cultivated area, and bajra, 102 square miles, or 26 per cent. Smaller areas are occupied by gram (30), maize (24), barley, pulses, and jowar. Very little rice or cotton is produced.

The cultivated area has apparently decreased by 3 per cent, since the previous settlement, as the lighThess of the revenue demand afforded no inducement for keeping the poorer soils under the plough, and no improvements have been made in agricultural methods. There is, however, room for expansion of cultivation, especially in Miranzai. Ad- vances for the repair of embankments and watercourses are in some demand, and Rs. 36,100 was lent during the five years ending 1903-4 under the Land Improvement Loans Act. During the same period Rs. 31,500 was advanced under the Agriculturists' Loans Act for the purchase of seed and bullocks.

The cattle bred locally are of poor quality, and animals are largely imported from the Punjab. Camels are bred in large numbers. Both the fat-tailed and ordinary breeds of sheep are found, and large flocks ot goats are kept. The local breed of horses is fair. Two puny and two donkey stallions are maintained by the municipality and the District board.

Out of the total cultivated area of 461 square miles, only 61 square miles, or 1 2 per cent., were irrigated in 1903-4. Of this area, 3-4 square miles were supplied by wells and 53-8 square miles by streams and tanks, in addition to which 4 square miles are subject to inundation from the Indus. There were 413 masonry wells worked by bullocks with Persian wheels, and 175 unbricked wells and water-lifts. The most effective irrigation is from perennial streams ; but agriculture, especially in Mlranzai, is much benefited by the building of tanks and embankments to hold up rain-water.

The District contains 74 square miles of unclassed forest and Gov- ernment waste under the management of the Deputy-Commissioner. Parts of the hill tracts are covered with dwarf-palm (mazri). The District as a whole is not well wooded, though where water is obtain- able roadside avenues have been planted, in which the mulberry, Per- sian lilac {bakain), willow, and shisham are preponderant. Elsewhere the palosi {Acacia modes/a) and other species of acacia, and the wild olive, are the commonest trees. The summit of the Samana has been almost denuded of trees, but in sheltered places ilex, walnut, and Scotch fir are found.

The salt-producing areas, from which salt has been excavated from time immemorial, occupy a tract about 50 miles long with a nearly uniform width of 20 miles. The Kohat Salt Quarries at present worked are at Jatta, Malgln, Kharak, and Bahadur Khel, of which the last presents perhaps the greatest amount of exposed rock-salt to be seen in the world. The average sales of salt for the three years ending 1903-4 exceeded 15,307 tons. The District contains three petroleum springs, which would yield perhaps half a gallon a day if the oil was gathered daily, but it is only occasionally taken. Sulphur is found in the hills to the south of the Kohat Toi, and limestone and sandstone all over the District, but they are not regularly quarried.

Trade and communications

The District possesses very few handicrafts and no manufactures. Kohat used to be celebrated for its rifles, in which a high degree of excellence was attained, considering the rude nature of the appliances; but the industry not being en- couraged has now departed to the independent villages of the Kohat pass, where it flourishes. Coarse cotton cloth is made throughout the District, but not in sufficient quantities to supply even the local demand. Turbans of excellent texture and colour are woven of both silk and cotton at Kohat and the adjoining villages, and coloured felt mats are made ; woollen camel-bags and leathern sandals are also produced. The dwarf-palm is used to a very large extent for the manufacture of sandals, ropes, mats, matting, and baskets.

A large and increasing trade with Tlrah and Kabul passes through the District by the Khushalgarh-Kohat-Thal Railway, but the imports and exports apart from this through traffic are not large. Salt, agricul- tural produce, and articles made of the dwarf-palm, which grows plentifully throughout the District, are the principal exports; and piece-goods and iron are the principal imports. Kohat, Thai, and Naryab are the chief trade centres.

The District is traversed by the 2 feet 6 inches gauge railway from Khushalgarh to Thai, opened in 1903. The line at once came into universal use for the conveyance of passengers and goods, and has proved an unexpected commercial success. It is being converted to the broad gauge, which will be opened on the completion of the bridge over the Indus at Khushalgarh. Mails and passengers are conveyed by tonga from Peshawar to Kohat over the Kohat pass and on to Bannu. There are 179 miles of Imperial metalled roads, and 509 miles of unmetalled roads. Of the latter, 131 miles are Imperial, and 378 belong to the District board. Besides the Peshawar-Kohat-Bannu road, the most important routes are those from Khushalgarh through Kohat to the Knrram at Thai and from Khushalgarh to Attock. There is little traffic on the Indus, which has a very swift current in this District ; it is crossed by a bridge of boats at Khushalgarh, now being replaced by a bridge which both road and rail will cross.

Famine

The District was classed by the Irrigation Commission as one of those secure from famine. The crops that matured in the famine year of 1 899-1 900 amounted to as much as 77 per cent, of the normal out-turn.

Administration

The District is divided for administrative purposes into three tahsil, each under a tahsildar and ?iaib-tahsildar. The Deputy-Commissioner has political control over the trans-border tribes in adjoining territory : namely, the Jowaki and Pass Afrldis, the Sepaiah Afrldis (Sipahs), the Orakzai Zaimukhts, the Biland Khel and Kabul Khel Wazlrs. Under him are two Assistant Com- missioners, one of whom is in charge of the Thai subdivision and exercises political control, supervised by the Deputy-Commissioner, over the tribes whose territories lie west of Fort Lockhart on the Samana range. Two Extra-Assistant Commissioners, one of whom is in charge of the District treasury, complete the District staff. One member of the staff is sometimes invested with the powers of an Additional District Magistrate.

The Deputy-Commissioner as District Magistrate is responsible for criminal justice, and in his capacity of District Judge has charge of the civil judicial work. He is supervised by the Divisional Judge of the Derajat Civil Division, and has under him a Subordinate Judge, whose appellate powers relieve him of most of the civil work, a Munsif at head-quarters, and an honorary civil judge at Teri. Crime is still very frequent and serious offences preponderate; but the advance in law and order during late years, especially since the Miranzai expedition of 1891, has been considerable.

The early history of Kohat, fiscal as well as political, is vague and uncertain. Under the Mughals and Afghans leases were granted in favour of the Khans, but few records remain to show even the nominal revenue. In 1700 the emperor Aurangzeb leased Upper and Lower Miranzai to the Khan of Hangu for Rs. 12,000. In 1810 the Kohat tahsil was leased for Rs. 33,000. In 1836 Ranjit Singh assigned the revenue of the whole of the present District to Sultan Muhammad Khan, Barakzai, in return for service. This revenue was estimated at 1 ½ lakhs.

After annexation four summary settlements were made of the Kohat and Hangu tahsil, which reduced the demand from one lakh to Rs. 75,000. In 1874 a regular settlement of the Kohat and Hangu tahsil was begun, excluding three tappas which were settled summarily. The rates fixed per acre varied from Rs. 6-8 on the best irrigated land to 3 annas on the worst ' dry ' land ; and the total assessment was Rs. 1,08,000 gross, an increase of 18 per cent, on the previous demand. So large a sum was granted in frontier remissions and other assign- ments that the net result to Government was a loss of Rs. 5,000 in land revenue realizations. The object of the settlement, however, was not so much to increase the Government demand as to give the people a fair record-of-rights. The increasing peace and security along this part of the border, culminating in the complete tranquillity which has characterized it since 1898, has worked an agricultural revolution in Upper Miranzai.

The Teri tahsil, which forms half the District, has a distinct fiscal history. The Khan of Teri has always paid a quit rent, which was Rs. 40,000 under the Barakzai rulers, and was fixed at Rs. 31,000 on annexation. Since then it has been gradually lowered to Rs. 20,000, at which it now stands. During the Afghan War the Khan's loyalty to the British exceeded that of his people, who resented the forced labour then imposed upon them by the Khan. Consequently at the close of the war a veiled rebellion broke out in Teri. It was therefore decided that the tract should be settled, and a settlement was carried out in 1891-4, the chief object being to place on a satisfactory footing the relations between the Khan and the revenue-payers.

In 1900 the first regular settlement of Upper Miranzai and the revision of settlement in the rest of the District was begun. This was completed in 1905 and resulted in a net increase of Rs. 59,000 in the revenue demand, which amounted to Rs. 1,28,000. The rates of the new settlement per acre are : 'dry' land, maximum Rs. 1-12, minimum 3 annas; and 'wet' land, maximum Rs. 7-12, minimum R. 1.

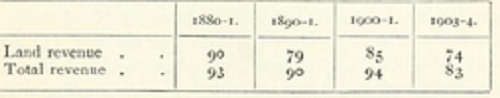

The total collections of revenue and of land revenue alone have been as follows, in thousands of rupees : —

The District contains only one municipality, Kohat Town. Outside this town, local affairs are managed by a District board, whose income is mainly derived from cesses. In 1903-4 the income amounted to Rs. 14,100, and the expenditure to Rs. 16,300, education forming the largest individual charge.

The regular police force consists of 527 of all ranks, of whom 44 are municipal police. The village watchmen number 265. There are 12 police stations, 16 road-posts, and 4 out-posts. The border military police, who are amalgamated with the local militia (the Samana Rifles), are under a commandant, assisted by a British adjutant and quarter- master, all of whom are officers of the regular police force. The control of the commandant is exercised subject to the orders of the Deputy-Commissioner. The force, which numbers 1,023 of all ranks, garrisons 23 posts for maintaining watch and ward on the border. The District jail at head-quarters can accommodate nearly 300 prisoners.

Only 4-2 per cent, of the population (7-2 males and 0-3 females) could read and write in 1901. The proportion is markedly higher amongst Sikhs (39-1 per cent.), and Hindus (29-5), than among the agricultural Muhammadans (i-6 per cent.). Owing to the difficulties of communication and the poverty of the District board, education con- tinues to be very backward, and the percentage of literacy compares unfavourably with that of the Province generally. The number of pupils under instruction was 375 in 1880-1, 536 in 1890-1, 908 in 1 900-1, and 1,260 in 1903-4. In the last year there were 2 secondary and 28 primary (public) schools, and 55 elementary (private) schools, the number of girls being 90 in the public and 230 in the private schools. The total expenditure was Rs. 16,000, of which fees brought in Rs. 2,400, the District fund contributed Rs. 5,000, the municipality Rs. 6,800, and Imperial revenues Rs. 2,600.

Besides the civil hospital at Kohat, and a branch in the town for females, the District possesses two dispensaries, at Hangu and Teri. The hospitals and dispensaries contain 57 beds. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 53,499, including 1,106 in-patients, and 2,100 operations were performed. The income was Rs. 10,800, Government contributing Rs. 3,800 and municipal and District funds Rs. 7,000.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 951, repre- senting 44 per 1,000 of the population. The Vaccination Act has been in force in Kohat since 1903.

{District Gazetteer, 1879 (under revision).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.