Kurnool District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Kurnool District

(vernacular Kandenavohi). — One of the four Ceded Districts in the Madras Presidency, lying between 14° 54' and 16° 18' N. and 77° 21' and 79° 34' E., with an area of 7,578 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Tungabhadra and Kistna rivers (which separate it from the Nizam's Dominions) ; on the north- east by Guntur District ; on the east by Nellore ; on the south by Cuddapah and Anantapur ; and on the west by Bellary.

Physical aspects

Two long ranges of hills, the Nali.amalais on the east and the Erramalas on the west, divide the District north and south into three well-defined sections : namely, the country east of Nallamalais, that between this range and the

Erramalas, and that west of the Erramalas. The easternmost of these sections, which includes the taluks of Cumbum and Markapur, is about 600 feet above sea-level and very hilly. Through- out the greater part of its length a range of hills known as the Velikondas (a part of the Eastern Ghats) divides it from Nellore.

Between this range and the Nallamalais to the west, several low parallel ridges cut up the country into valleys, and through these the hill streams draining the eastern slopes of the Nallamalais have forced their way. Some of the gorges thus hollowed out have been dammed, and tanks made in them for purposes of irrigation. The tank at CuMBUM, formed by an embankment across the Gundlakamma river, is the most magnificent instance of this enterprise. Two passes, the Mantralamma, or Dornal, and the Nandikanama, lead across the Nallamalais into the central section of the District, and the Southern Mahratta Railway is carried through the latter. This central section, the Nandyal valley, is for the most part a flat open valley, between 700 and 800 feet above sea-level and covered with black cotton soil.

It is crossed from east to west by the great watershed between the Kistna and Penner river systems ; and it is drained to the south by the Kunderu, a tributary of the latter river, and to the north by the Bavanasi and other minor streams which fall into the former. From the east, the Nallamalais run down to meet it, while on the west the Erramalas rise up gradually into a series of flat-topped plateaux. In the dry season the valley presents a most arid appearance, but the Nallamalais on the east of it are always green. It includes the taluks of Nandikotkur, Nandyal, Sirvel, and Koilkuntla, and the Native State of Banganapalle. The Kurnool-Cuddapah irrigation canal passes down the centre and commands a large area.

Passing westwards over the Erramalas, which from the west present a clear and well-defined scarp gradually diminishing in height from south to north, the western section of the District, consisting of the two taluks of Pattikonda and Ramalla- kota, is reached. This section forms the north-eastern extremity of the Mysore plateau and is drained towards the north by the Hindri, a tributary of the Tungabhadra. The southern portion (except where it opens out into the Bellary black cotton soil plain) is much broken by rocky hills and long ridges of granitoid gneiss, and is covered with thin, poor, gravell)' land. Northwards and westwards the country opens out, until near Kurnool it becomes an almost unbroken plain of black cotton soil.

The chief rivers of Kurnool are the Tungabhadra and Kistna already mentioned, while several smaller streams drain the three sections referred to above. The chief of those in the eastern section are the Gundlakamma and its tributaries, the Ralla Vagu, Tigaleru, Kandleru, and Duvvaleru, all rising in the Nallamalais. The Gundlakamma has its source near Gundlabrahmeswaram and enters the plains through the gorge of Curabum, where it is held up by a dam 57 feet in height to form the Cumbum tank, about 15 square miles in extent.

The river carries away the surplus escape of the tank, receives several tributaries, and runs in a north-easterly direction, lorming the north- eastern boundary of the District. The Sagileru, also rising in the Nallamalais, flows south and drains the country towards the Penner in Cuddapah District. The chief rivers in the central section of the District are the Kunderu and Bavanasi. The former rises in the Erramalas, and after receiving its most important tributary, the Galeru or Kali, which rises in the Nallamalais, flows southwards to join the Penner in Cuddapah District. The Bavanasi, which rises in the Nalla- malais, drains into the Kistna the country lying to the north of the watershed between that river and the Penner. The only river of importance in the western section is the Hindri, which rises in the Pattikonda taluk and falls into the Tungabhadra at Kurnool town. Its chief tributaries are the Dhone Vagu and Hukri. The portion of this western section which lies to the north of the railway line drains into the Hindri.

Geologically, Kurnool is situated in the centre of a basin occupied by the two great azoic formations known as the Cuddapah and Kurnool systems. The geological characteristics of each of the three natural divisions of the District are distinct. The eastern section belongs to the Cuddapah system, the prevailing rocks of which are slates over quartzites. The central portion belongs to the Kurnool system, the chief rocks of which are limestones and quartzites. The former make very good building material. The portion of the western section adjoining the Erramalas belongs to the Cuddapah system, while that part of it which lies in the extreme w-est of the District is occupied by crystalline or Archaean formations consisting of granitic rocks of no peculiar interest.

The Nallamalai forests, which are about 2,000 square miles in extent, are the finest in this part of the Presidency and contain a large variety of trees. The chief of these are referred to below under Forests. Elsewhere the flora of Kurnool is that of the drier zones of the Presidency. Fibre-producing plants and .trees are common, among them being roselle, some of the Bauhinias, Buteafrondosa, and Calotropis gigafitea. In the villages, mangoes, tamarinds, and iluppais grow freely in plantations and groves, and date-palms {Phoenix sylvestris), which produce the alcoholic liquor of the District, flourish in the damper hollows. Coco-nut palms, however, are not grown extensively, the soil being unsuited to them, and palmyras are only to be seen in a few villages.

The hill country contains all the game usual to such localities. Tigers and bears are found on the Nallamalais, while wolves are met with all over the District, though not in large numbers. Crocodiles infest the Tungabhadra and Kistna, and in some places lie in pools near the bathing ghdis where human victims are easy to obtain. l^Iahseer of unusual size are occasionally taken in these rivers. The game-birds include sand-grouse and jungle-fowl.

The climate of Kurnool cannot be said to be healthy. The temperature in the shade goes up to 112° in the months of April and May and falls to 67° in November, the mean averaging about 82°. The period from February to May is hot, particularly so in April and May. In June the south-west monsoon begins, and it lasts till September. The north-east monsoon brings some rain in October. Malarial fever is \ery prevalent almost everywhere, and especially so in the villages bordering on the Nallamalais. Cluinea-worm and enlarged spleen, from which man\- of the inhabitants suffer, are due to the impurity of the water-supply.

The rainfall is light and irregular, and the whole of the District is included within the famine zone of the Presidency. The central or Nandyal valley section has, as a whole, the least scanty fall in the District; but on the other hand parts of it, such as Owk, have the lightest. The average annual rainfall there is under i8 inches; for the whole District it is 26 inches. Except in the eastern section, where both the monsoons contribute equally, more than three-fourths of the annual supply is received during the south-west monsoon (June to September), which is consequently most important to the welfare of the country. This current, however, is exceedingly capricious and uncertain, and Kurnool is liable to frequent scarcity. Natural calamities other than famine have happily been rare. In 1851, however, unusually heavy floods in the Tungabhadra destroyed the crops in several villages, and washed away some buildings in the lower part of Kurnool town.

History

Up to the conquest and occupation of the District by the Vijaya- nagar kings, nothing definite is known of its history ; but it seems probable that it was successively in the hands of the Chalukyas, the Cholas, and the Ganpatis of Warangal. About the sixteenth century, Krishna Raya, the greatest of the A^ijaya- nagar dynasty, annexed the whole of it. On the break-up of his line after the disastrous defeat at Talikota in 1565 by the united Deccan Muhammadans, the District was overrun by one of the victors, the Kutb Shahi Sultan of Golconda. It was also the scene of later Musalman invasions. In 1687 Aurangzeb subdued the country south of the Kistna, and Ghiyas-ud-din, one of his generals, took Kurnool.

Shortly afterwards the District was conferred as ^jdgir on Daud Khan, a Pathan general who had rendered important military service to the Mughals. Himayat Khan succeeded in 1733. During his rule, in 1 741, the Marathas invaded the District, and their ravages are even now described in popular ballads. Himayat Khan played an important part in the Carnatic \\'ars of the eighteenth century, proving treacherous alternately to the English and to the French. Kurnool was besieged and carried by assault in March, 1751, by Salabat Jang and the French general Bussy. In 1752 ISIunavvar Khan became Nawab.

In 1755 Haidar All, who subsequently usurped the Mysore throne, marched against Kurnool, and levied tribute. In the redistribution of territory that followed the final defeat and death of Tipu, Haidar's son and successor, in 1799, the District fell" to the share of the Nizam. He ceded it in iSoo to the British, in payment for a subsidiary force to be stationed in his territories ; but the Nawab of Kurnool was left in possession of his jcigir, subject to a tribute of a lakh of rupees. The Pindaris plundered the country in 1816 during the time of Munavvar Khan. The latter was succeeded in 1823 by his brother Ghulam Rasul Khan, the last of the Nawabs. In 1838 this man was found to be engaged in treasonable preparations on an extensive scale, and in the next year he was sent to Trichinopoly, where he was subsequently murdered by his own servant.

His territories, with the minor jdglrs enjoyed by his nobles and relatives, were annexed, and the members of his family were liberally pensioned. Since then the peace of the District has been but once disturbed, by a descendant of a dispossessed poligdr in 1846. He was, however, captured and publicly hanged. From 1839 to 1858, the territory taken from the Nawab (consisting of the four tdliiks of Ramallakota, Nandikotkur, Nandyal, and Sirvel) was administered by a British Commissioner and Agent. In 1858 three taluks of Cuddapah (Koilkuntla, Cumbum, and Markapur) and the Pattikonda tCxluk of Bellary were added to Kurnool proper, and the whole was formed into the present Collectorate.

Kurnool possesses few remains of archaeological interest. The Srisailam plateau on the Nallamalais contains the ruins of old forts, houses, and towns, showing that it was inhabited by prosperous com- munities in olden days. Almost every town in the District has a ruined fort and every village its own keep. Dolmens or cromlechs are found in some villages of Markapur and Cumbum. The most important Hindu temples are those at Srisailam and Ahobilam on the Nalla- malais.

Population

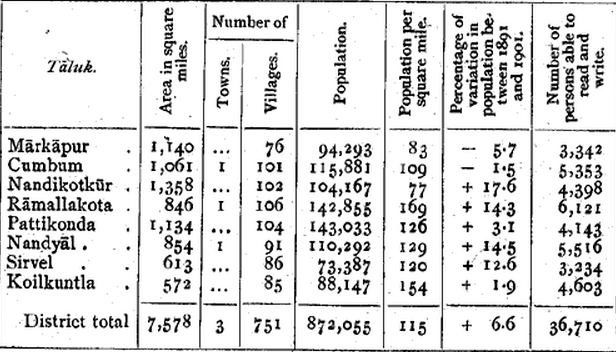

The number of towns and villages in the District is 3 and 751 respectively. It is divided into eight taluks, of which statistics according to the Census of 1901 are given below : —

Except in the cases of Ramallakota, Sirvel, and Cumbum (the head- quarters of which, are respectively Kurnool, Allagadda, and Giddalur), the head-quarters of the taluks are at the places from which each is named. The density of the population in Markapur and Nandikotkur is less than loo per square mile, and the District as a whole is more sparsely populated than any other in the Presidency. The population in 1871 was 914,432 ; in 1881, 678,551 ; in 1891, 817,81 1 ; and in 1901, 872,055. The great decHne in 1881 was due to the famine of 1876-8, and the population has not even yet regained the numbers then lost. During the decade ending 1901, the District again suffered from adverse seasons, especially in the Cumbum and Markapur taluks, and the population of both these areas declined ; but on the whole the advance was little below the normal.

The three towns are the two municipalities of Kurnool (population, 25,376), the head-quarters, and Naxdval (15,137), and the Union of Cumbum (6,502). The total urban population is less than in any District except the Nilgiris, and as many as 95 per cent, of the people live in villages. Classified according to religion, Hindus number 728,782; Muhammadans, 107,626, or 12 per cent, of the total, a higher proportion than in any other Madras District except Malabar ; and Christians, 30,043, or 4 per cent. The last have nearly trebled during the past twenty years, and they increased by 50 per cent, in the decade ending 1901. About three-fourths of them are Baptists and another fifth Anglicans. The same unexplained defi- ciency of females occurs in Kurnool as in the other Deccan Districts.

The District contains a smaller proportion of Eurasians than any other, and a smaller percentage of Europeans than any other except Cuddapah. Apart from the wandering tribe of the Kuravans, the gipsy Lambadis, and 23,000 Kanarese-speaking Kurubas (shepherds), the Hindus are nearly all Telugus, the most numerous caste being the Kapu cultivators, 121,000 strong. Next to them come the Boyas, numbering 86,000. They are the great shikari caste of the Deccan, and are fine fearless fellows. Nowadays many of them have taken to agriculture ; and two well-marked divisions, the Myasa (forest) Boyas and the Uru (village) Boyas, have arisen, of whom the latter are the more advanced in their ideas. The caste is interesting as being one of the few in which survivals of totemism have been found. Perhaps, however, the most curious of the Kurnool castes are the forest people called the Chenchus, who mainly live on the Nallamalais in small clusters of little round huts. Of the Musalmans, the majority, as usual, are Shaikhs, but Dudekulas (a mixed race which follows many Hindu customs) and Saiyids are also numerous. The occupations of the people present no points of particular interest. As many as 74 per cent, subsist by callings connected with agriculture or pasture ; and the only directions in which their means of livelihood show notable varia- tions from the normal are in the considerable percentage of weavers, and the small proportion of those who live by the professions.

The American Baptist Mission has stations at Kurnool, Cumbum, and Markapur. The London Mission, formerly at Xandyal, has now resigned that field to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. The Roman Catholic missions are in a less flourishing condition than farther south. Their chief station is Polur, near Nandyal.

Agriculture

The soils of the District are either red or black. In the eastern section the prevailing variety of land is red, of a poor, thin, gravelly description, though patches of black cotton soil and red clay are found here and there in the valleys of the Tigaleru, Gundlakamma, and Sagileru. These red earths, being generally formed from disintegrated particles of the gneiss, mica, quartz, and altered sandstone of which the hills are composed, are generally speaking inferior, lying over rock which is only a few inches below the surface. The poverty of the soil is, however, in some degree com- pen.sated by the facilities which exist for the digging of wells on the river banks ; almost all the well-irrigation in the District is confined to this section. The central or Xandyal valley section consists almost entirely of black cotton soil. The southern part of the western section is covered with a thin, poor, gravelly earth, but northv>'ards and west- wards stiff black cotton soil replaces the gravels. Roughly speaking, a fourth of it consists of red earth and the remaining three-fourths of black cotton soil. The District is essentially one producing ' dry crops,' and the sowing season is spread over the period from July to November. The great part of the early sowings up to August takes place on the light soils, and those which follow, between September and November, are on the heavier land. By the middle of November sowing is practically over.

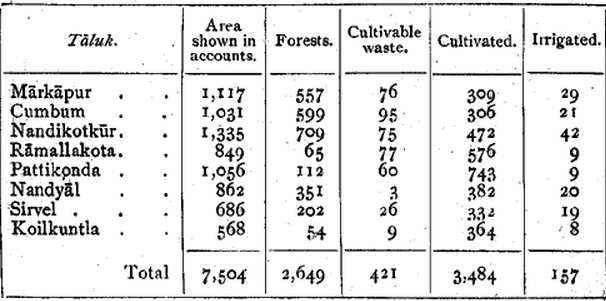

The District is almost entirely ryohvdri, there being no zamlnddris in it. The area of the 'whole indm' villages is 204 .square miles. Statistics for 1903-4 of the area for which particulars are on record are given below, in square miles :—

Forests occupy 34 per cent, of the total area, and the cultivable waste is only about 5 per cent. The staple food-grains are cholam {Sorghum vulgare) and korra {Setaria ifalica), the area under them being 884 and 598 square miles respectively, or 27 and 19 per cent, of the total area cropped in 1903-4. The former is the most important crop of the four central and two western taluks, while korra, rdgi {Eleusine coracana), and caiiiliu {Pennisetum typhoideum) are the chief staples of the two taluks of the eastern section. Nearly 90 per cent, of the area under rdgi and 50 per cent, of that under cambu is in these two taluks.

Generally speaking, korra and cambu are raised on the poorer red soils, while cholam is the chief crop of the black cotton soils. Horse-gram is also extensively grown, especially in Pattikonda, Cumbum, and Marka- pur. The area under rice is comparatively small, being only 128 square miles. Next to cholam and korra, cotton is the crop most extensively cultivated, covering 430 square miles. Almost the whole of it is raised in the five black-soil taluks west of the Nallamalais. The area under oilseeds is also comparatively extensive, being 2 1 7 square miles ; nearly two-thirds of this lie in the two taluks of Ramallakota and Pattikonda.

The extension of the area of holdings during the last thirty years has amounted to 7 per cent. ; and considering the terrible mortality during the great famine of 1876-8 and the fact that the population is still 4 per cent, below what it was in 187 1, this rate of increase may be regarded as fliir. ' Wet ' holdings, however, have remained almost stationary in area, notwithstanding the facilities afforded by the KuRNOOL-CuDDAPAH Canal. There are still large areas of arable land in all the taluks except Nandyal, Sirvel, and Koilkuntla. ^'ery little improvement is perceptible in the quality of the crops grown, and the ryots cling to their primitive methods of cultivation. The Mauritius sugar-cane, which is said to have been introduced in 1843, has however ousted the indigenous variety, except in Cumbum. Unless during famine or scarcity, the Kurnool ryots have not been anxious to avail themselves of the benefits of the Loans Acts. The total amount advanced during the sixteen years ending 1904 was a little over 7 lakhs ; but the greater part of this appears to have been spent on the improvement of land, such as the removal of deep-rooted grass, the building of stone boundary walls, &c., and very little in the digging of wells. Most of the few wells which have been made are in the Marka- pur subdivision.

Kurnool cannot be said to be rich in horned cattle. Two-thirds of the animals used, especially those intended for the ploughing of the heavy black cotton soils, are imported from Nellore, Guntur, and Kistna. The cattle bred in the District itself are smaller, but more hardy, than the coast bullocks. They are good trotters, but unfit for tilling heavy land. The eastern section of the District is comparatively richer than the rest in cattle and sheep, on account of the never-faihng pasture on the Nallamalais. In the central section considerable herds of breeding cattle are maintained in the villages bordering upon the Nallamalais and Erramalas, where there is abundant pasturage ; but in the central part of the valley few animals are kept besides the plough bullocks, most of which are imported animals of the Nellore breed. In the western tdliiks also the stock for the cotton-soil land is provided from Nellore. A considerable number of buffaloes are bred for export. There are three varieties of sheep — the black, the brown, and the white. The last variety is confined to Cumbum and Markapur. The species in the western taluks are black and brown. The black sheep yield a short wool, which is shorn twice a year and made into rough blankets. The brown sheep are covered with hair instead of wool and are valued only for their flesh. Goats are bred mainly for their manure. There is no local breed of ponies.

The District is essentially an unirrigated area. Of the total ryotwdri and indm area cultivated in 1903-4, only 157 square miles, or \\ per cent., were irrigated. Of this portion, 74 square miles were watered from tanks, 32 square miles from Government canals and channels, and 31 square miles from wells. More than one-third of the area supplied by tanks is in the two taluks of Markapur and Cumbum, where the country is best adapted for the formation of reservoirs.

The biggest tanks in the District are those at Cumbum, irrigating g,ooo acres of first and second crop, at Nandyal, and at Owk and Timmanayanipet in the Koilkuntla taluk. In former days ryots were encouraged to form tanks at their own cost, in return for the grant of lands free of rent or the assignment of a portion of the land revenue for their main- tenance and repairs. These were called dasabafidam sources. The greater part of the area irrigated by them (more than 85 per cent.) lies in the single Taluk of Markapur.

The Kurnool-Cuddapah Canal irri- gates 25,000 acres in the five Taluks through which it passes, and more than a third of this area lies in Nandikotkur. In some of the villages bordering upon the Nallamalais and Erramalas, the hot springs which lie at the foot of these ranges are the chief sources of irrigation. The most important of these, all of which are perennial, are at Mahanandi, Kalwa, Dhone, and Brahmagundam. Of the total area irrigated from wells, two-thirds is in the single Taluk of Markapur. The number of these sources is 10,868. In the Pattikonda Taluk there are many doraV2i wells, or baling-places made on the banks of rivers and streams. The lands served by them were classed as 'wet' at the settlement. The numerous jungle streams in the District are not used directly for irrigation, except where the configuration of the country has facilitated the formation of tanks. There are, however, numerous doravu wells on their banks — especially along the Gondlakamma, Hindri, and Bavanasi. The lands supplied by those on the banks of the Gund- lakamma are exempted from water rate on account of the high cost of constructing the wells, but those irrigated from the others are charged with an additional assessment, and valuable garden crops are raised. Leathern buckets drawn up with a rope and pulley by cattle working down an inclined plane are universally used for lifting the water.

Forests

From both their extent and nature, the forests of Kurnool are important. Their total area in 1903-4 was 2,649 square miles, the Nallamalais alone comprising one vast expanse of 2,000 square miles, rsext m miportance are the forests on the Erramalas, and last the Velikonda forests. On account of the extensive area to be managed, the District has recently been divided into the two forest charges of East and West Kurnool. The greater part of the growth on the Nallamalais is still untouched.

This area affords ample pasturage at all times of the year, and to it are driven the cattle of the Districts of Nellore and Guntur during the summer. It is the chief .source of the fuel supplied to the Southern Mahratta Railway. The more valuable timber trees are teak, red- sanders, 7iaUaviaddi {Terminalia tome/ifosa), egi (Pterocarpus MarsK- pii/m), jittegi (black-wood), and yepi {Hardivickia hinata). Sandal-wood is found near Srisailam, but it is not as strongly scented as the wood of the Coimbatore and Mysore forests. Bamboos are also plentiful. The Velikonda forests contain the same species as the Nallamalais, but they do not grow to as great a size. The Erramala forests are of minor importance and contain no valuable timber. These hills are gene- rally bare of growth on their flat tops ; but the slopes are clothed with stunted trees and shrubs which, however, are only fit for fire- wood.

The minerals of the District are hardly worked at all, but some Madras firms have taken out prospecting licences. Iron ore is plentiful on both the Erramalas and Nallamalais. That found on the Gani hill is said to be the best. Iron was smelted in a hill called Inapartikonda near veldurti (Ramallakota taluk) till a few years ago, but the industry has now been abandoned. The chief smelting centre at present is Rudravaram, a village at the foot of the Nallamalais in the Sirvel taluk. The ore worked here is generally a massive, shaly, iron sandstone. The iron produced is largely used for ploughs and other agricultural implements. Copper mines were formerly worked in Gani. Lead is found near Gazulapalle at the foot of the Nallamalais in the Nandyal taluk. Diamond mines were formerly worked on a large scale in Banganapalle, Munimadugu, and Ramallakota.

Trade and Communication

The only important industries in the District are cotton-weaving and the manufacture of cotton carpets. The cotton-weaving is of the ordinary kind, only coarse cloths being made. Cotton carpets of a superior description are made at Kurnool and Cumbum. The manu- facture of lacquered wares and paintings on leather is on in Nandyal and Nosam (Koilkuntla tdlnk). Thick woollen blankets are woven in some villages of the Nandikotkur taluk.

There are four cotton-presses, two at Nandyal owned by Europeans, and two at Kurnool by natives. All four are worked by steam. They clean or press the local cotton for export to Bombay and Madras. In 1904 the two Nandyal presses employed on an average 119 hands. The presses at Kurnool are smaller concerns, the average number of hands employed being less than 25. The grow- ing of rubber-producing plants has recently been started in Kurnool under European supervision. A tannery has also been working there for the last four years.

Commercially, the District is of small importance. The chief exports are cotton, turmeric, tobacco, ghi, gum, honey, melons, oil- seeds, onions, indigo, timber, woollen blankets, cotton cloths, and cotton carpets ; while European piece-goods, salt, areca-nuts, coco-nuts, sugar, jaggery (coarse sugar), brass and copper utensils, cattle, and various condiments required for Indian households are the chief imports. There is usually no export of grain, but in 1900 a large quantity was sent to Bombay, where the distress was acute and prices correspondingly high. Trade is chiefly with the neighbouring Districts and Hyderabad. Salt, however, is imported from Bombay, and cotton is exported to that city and Madras. Gh'i, melons, cotton carpets, and timber are sent to Hyderabad by the trunk road connecting the two places. Sugar and jaggery are obtained from North Arcot, and piece- goods and utensils from Bellary and Madras.

Kurnool, Nandyal, and Cumbum are the centres of trade for the western, central, and eastern divisions of the District respectively. Nandyal is, however, outstripping Kurnool in commercial importance, as it is on the railway, while Kurnool is 33 miles from the nearest station. The Komatis are the chief merchants, but latterly many Musalmans have taken to trade. Two large European firms have agencies at Kurnool and Nandyal for their cotton business. Most of the internal trade is effected through the agency of weekly markets. Thirteen of these are under the management of the local boards, and the fees levied in them in 1903-4 yielded Rs. 1,850. The most important are at Nandyal, Gudur, Pattikonda, and Koilkuntla.

The Southern Mahratta Railway (metre gauge) enters the District about 2 miles to the west of Maddikera in the Pattikonda taluk, and runs across from west to east, till it reaches Cumbum, where it turns northwards along the eastern border. It places all parts of the District within 30 miles of a railway, which taps at its eastern extremities the rich grain-growing deltas of the Godavari and the Kistna, and is thus a valuable defence in time of famine. The line was opened for trafific to Nandyal in 1887, and thence to Cumbum and Tadepalle in 1889-90. The Madras Railway (broad gauge) also touches the District in a corner of the Pattikonda taluk.

The total length of metalled roads is 547 miles, and of unmetalled roads 171 miles, all of which are maintained from Local funds. There are avenues of trees along 606 miles. The western section is fairly well provided with communications, trunk roads branching from Kurnool to Bellary, Gooty, Cuddapah, and Hyderabad. The Nandikotkur and Nandyal tdbiks are also provided with good roads, the facilities thus afforded being supplemented by the irrigation canal which runs through the middle of them and is navigable throughout its course. The remaining four taluks are deficient in communications. There are two ghat roads over the Erramalas — the Tammarazupalle pass and the Rampur pass. Neither of the roads across the Nallamalais — namely, the Mantralamma pass and the Nandikanama pass (the latter of which was formerly the highway between the coast and the interior) — is now much used, and they are becoming impassable.

Famine

The whole District lies within the famine zone, and has suffered nine times from want of rain since the beginning of the last century : namely, in the years 1804, 1820, 1824, 1833, 1853-4, 1866, 1876-8, 1891-2, and 1896-7. In 1873-4, also, parts of it suffered, and in 1884 there was widespread distress. The season was again bad in 1900 in some portions. No statistics are available of the relief given previous to 1866. The average number of persons relieved in that year was 1,741, while the maximum number relieved in any one month was 2,727 in October.

In 1876 both monsoons failed and prices rose enormously. The average number of persons relieved daily during the twenty-two months from December, 1876, to September, 1878, was 140,025, of whom 32,596 were relieved gratuitously and the remainder employed on works. The maximum number relieved in any one month was 299,804, or as much as 31 per cent, of the total popula- tion. The mortality caused by starvation and the diseases incidental thereto will never be known accurately, but the Census of 1881 showed that the population had decreased since 187 1 by 26 per cent. No other District in the Presidency exhibited so terrible a decline. During the famine of 1 891-2, in which the Taluk of Cumbum suffered worst, the average daily number of persons relieved was 14,107. The last serious famine was that of 1896-7. The average number relieved daily was 52,736, exclusive of 12,788 persons on gratuitous relief. The maximum number of persons on relief works in any one month was 170,289 in July, 1897. In this famine the expenditure in Kurnool District alone was 21 lakhs.

Administration

For administrative purposes Kurnool is divided into four subdivisions, one of which is in charge of a member of the Indian Civil Service, while the others are under Deputy-Collectors recruited ' in India. The subdivisions are Nandyal (the Civilian's charge), comprising the tdhiks of Nandyal, Sirvel, and Koilkuntla ; Markapur, comprising the Markapur and Cumbum taluks ; Kurnool, comprising Ramallakota and Pattikonda; and the head-quarters sub- division, which consists of the single taluk of Nandikotkur. A tahsil- ddr is stationed at the head-quarters of each Taluk, and a stationary sub-magistrate in three of them : namely, Nandyal, Ramallakota, and Pattikonda. In addition to the usual District staff there are two District Forest officers, and a special Deputy-Collector in charge of the irrigation from the Kurnool-Cuddapah Canal.

There are three regular District Munsifs' courts — at Kurnool, Nandyal, and Markapur. Appeals from these, as well as from the District Munsif of Gooty in Anantapur, lie to the District Judge of Kurnool. The Court of Sessions tries the sessions cases which arise within the District and in the Gooty and Tadpatri taluks outside it, and hears appeals from the convictions passed by the first-class magistrates. Dacoities, robberies, housebreakings, and thefts fluctuate in numbers, as elsewhere, with the state of the season, but propor- tionately to the population are more than usually common. The District has indeed the reputation of being one of the most criminal in the Presidency. Murders are especially frequent, being usually due to private personal motives or disputes about land. These land dis- putes often lead to serious riots, and the Koilkuntla taluk is notorious for such disturbances. The Donga (thief) Oddes are the most criminal class. Their profession may be said to be thieving and robbing, and they are very brutal in their treatment of their victims.

As already stated, the District consists historically of two portions : namely, Kurnool proper, consisting of the Ramallakota, Nandikotkur, Nandyal, and Sirvel taluks ; and the four transferred taluks of Cumbum, Markapur, Koilkuntla, and Pattikonda. The revenue history of these two tracts is distinct. The history of the transferred taluks is identical with that of the Districts from which they were transferred. Little definite is known of the methods of assessment under pre-British rulers in them. The villages were rented out to poligdrs, who paid a peshkash, or tribute, and sometimes rendered military service. This tract came into the possession of the British in 1800, when Major (afterwards Sir Thomas) Munro, the first administrator of the Ceded Districts, introduced a rough field survey and settled the lands on a (\\xdi?,\-ryot'wdri system.

But his rates were fixed with reference to the high assessment levied under the Musalman governments, and were excessive. Sir Thomas eventually himself recommended a reduction of 2-^ per cent, in the assessments on 'dry' and 'wet' lands and an additional 8 per cent, on garden lands, but his recommendations were not accepted. After his departure to England in 1807, the villages were rented out on a triennial lease, and again on a decennial lease from 1 8 10. Many of the lessees fell heavily into arrears and the renting system was discontinued in 182 1. Later, Munro, who had returned as Governor of Madras, was able to carry out his old recom- mendations. The ryottvdri system was reintroduced, with the reductions in the rates which he had proposed. Since then no sweeping changes have occurred, except the exemption from extra assessment of land irrigated from wells and tanks constructed at private expense, the assimilation of 'garden' rates to 'dry' rates, and the abolition of the tax on special products. After the formation of the District as it now stands in 1858, a survey and settlement on modern lines were made: and the new rates were introduced in Pattikonda in 1872, in Koilkuntla in 1874, and in Cumbum and Markapur in 1877.

In the case of Kurnool proper, very little is known of the former revenue history. The giidikaiiii, the only old record of importance, contains in detail the boundaries of each village and the extent and descriptions of all the lands in it, but no figures of assessment. During the Hindu period, the village lease system appears to have been the ordinary mode of settlement, the headman distributing the land with reference to the means of the ryots, and the fields being roughly classed with reference to the nature of their soil. The same system was continued under Muhammadan rule, but the manner of assessment was arbitrary and the methods of collection iniquitous. The demand was increased or lowered at the caprice of the Nawab.

A curious instance of arbitrary increase is on record. .A sum of Rs. 5,000 was added to the demand on the village of Nannur because a horse belonging to the Nawab died there. The result of these exac- tions was that the inhabitants fled and land was left waste. After the assumption of the territory by the British in 1839, a rcfj/z^/^rr/ settlement was introduced in 1840. This was followed in 1841 by a rough field survey which took two years to complete; and in 1843 the Commis- sioner, Mr. Bayley, prepared an elaborate scheme of field-assessment. His successor urged a reversion to the renting system, but the Board negatived the proposal.

The ryotwdri system was continued, and the only general change in the assessment was the abolition of the tax on special products. The great rise in prices which had taken place since the assumption of the territory compensated in some measure for the heaviness and inequalities of the assessment, though temporary remissions were granted year after year. All these inequalities were eventually removed by a survey and settlement on modern principles.

In 1858 a new survey was begun, and the settlement was introduced in 1865 and completed in 1868. The survey found an excess in the cultivated area of 3^ per cent, over that shown in the revenue accounts of the whole District, but the enhancement of revenue, consequent upon the settlement, was proportionately less. The average assessment on 'dry' land is now Rs. 1-4-1 1 per acre (maximum Rs. 5, minimum 4 annas), and on 'wet' land Rs. 5-14 (maximum Rs. 10, minimum Rs. 2-8).

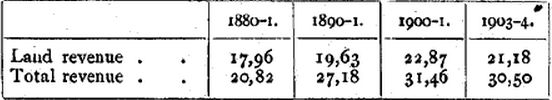

The revenue from land and the total revenue in recent years are given below, in thousands of rupees : —

Outside the two municipalities of Kurnool and Nandyal, local affairs

are managed by the District board and the four taluk boards of Ram-

allakota, Nandikotkur, Nandyal, and Markapur, the areas under which

correspond with those of the four administrative subdivisions. The

total expenditure of these boards in 1903-4 was 2 lakhs, nearly half

of which was laid out on roads and a third on medical services and

institutions. The chief source of their income is, as usual, the land cess.

A portion of the cess is reserved for future expenditure on railways. In

addition, the affairs of sixteen of the smaller towns are managed by

patichdyats established under Madras Act V of 1884.

The head of the police in the District is the Superintendent, who has an Assistant at Nandyal. There are 81 police stations; and in 1904 the force numbered 932 head constables and constables, working under 19 inspectors, besides 806 rural police. There are 12 subsidiary jails which can collectively accommodate 808 prisoners.

As in the other Deccan Districts, education is very backward in Kurnool. It stands nineteenth among the twenty-two Districts of the Presidency in the literacy of its population, of whom only 4-2 per cent.

(7-9 males and 0-4 females) are able to read and write. Markapur and Pattikonda are the least literate, and Nandyal is the most advanced, among the taluks. The total number of pupils under instruction in 1880-1 was 5,437; in 1890-1, 10,275; in 1900-1, 16,122; and in 1903-4, 18,290. On March 31, 1904, 656 institutions were classed as public, of which 5 were managed by the Educational department, 97 by local boards, and 6 by municipalities, while 292 were aided by public funds and 256 were unaided but conformed to the rules of the department. Of these, 647 were primary, 7 were secondary, and 2 train- ing schools.

There were, in addition, 116 private schools, with 1,681 pupils. Two of these, with a strength of 97, were classed as advanced. More than 96 per cent, of the pupils under instruction were only in primary classes, and only 15 out of the 2,438 girls at school had proceeded beyond that stage. Of the male population of school-going age, 21 per cent, were in the primary stage, and of the female popu- lation of the same age 4 per cent., which is rather a high proportion for the Deccan. Among Musalmans, the corresponding percentages were 38 and 5. The Kurnool Muhammadans are the most illiterate in the Presidency. There were 228 schools for Panchamas, or de- pressed castes, giving instruction to 900 pupils. A few schools have also been opened for the Chenchus on the Nallamalai hills. There are two high schools, one at Kurnool town and the other at Nandyal. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 92,500, of which Rs. 25,000 was derived from fees. Of the total, 78 per cent, was devoted to primary schools.

The District possesses 3 hospitals and 12 dispensaries, which contain accommodation for 60 in-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 118,000, of whom 830 were in-patients, and 1,900 opera- tions were performed. The expenditure amounted to Rs. 25,400, the greater part of which was met from Local and municipal funds.

Vaccination has of late been receiving considerable attention, and in 1903-4 the number of persons successfully treated by the Local fund and municipal vaccinators together was 33 per 1,000, compared with a Presidency average of 30. Vaccination is compulsory in the two municipalities, but in none of the sixteen Unions.

[For further particulars of the District, see the Kurnool District Manual, by Gopalkristnamah Chetty (1886).]