Mrinal Sen

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Early life

By Neil Genzlinger, January 3, 2019: The Yew York Times

From: Priyanka Dasgupta, December 31, 2018: The Times of India

From: By Neil Genzlinger, January 3, 2019: The Yew York Times

Mrinal (MREE-naal) Sen was born on May 14, 1923, in Faridpur, in what is now in Bangladesh, to Dinesh and Sarajubala (Tuli) Sen. He grew up in Faridpur and went to Calcutta to attend Scottish Church College.

He studied physics there but never finished his degree. Instead he became active in political movements and the Indian People’s Theater Association, a cultural affiliate of India’s Communist Party.

He found work as an audio technician at a studio in the city.

“My work only involved soldering capacitors and condensers,” he said in an interview in the early 1970s with Gary Crowdus, later the founder of Cineaste magazine, whose website published the interview last year. “I didn’t like that job at all, so I left. But I thought it would be a good idea to educate myself in the techniques of sound recording, so I started to read about it.”

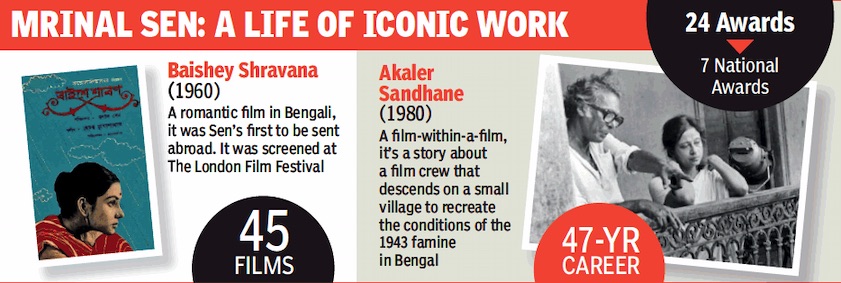

Mr. Sen began making films in the mid-1950s, exploring societal divisions and other themes in movies like “Baishey Shravana” (“The Wedding Day,” 1960), about a dumpy middle-aged man who marries a teenager, and “Akash Kusum” (“In the Clouds,” 1965), about a lower-middle-class man who inflates his credentials to try to win over a young woman.

In 1969 he earned wide acclaim with “Bhuvan Shome,” whose title character, a rigid railroad official, takes a life-altering hunting trip. The movie, named best feature at India’s National Film Awards, established Mr. Sen as a major director and is considered a foundational film of what is sometimes called India’s new wave cinema, whose realism and small-scale storytelling contrasted with the grandiose fantasies, singing and dancing of Bollywood.

In the 1970s Mr. Sen’s films showed his Marxist leanings and his fascination with the teeming city then known as Calcutta, now Kolkata. The 1980s brought several of his movies recognition at Cannes and other international film festivals.

One day in 1943, while doing research in a library, he pulled out a book on film aesthetics, and thus began his interest in films and filmmaking.

He began writing about film, and in 1956 he made his first movie, “Raat Bhore” (“The Dawn”) — “It was very bad, a disaster,” he told Mr. Crowdus. Then came “Neel Akasher Neechey” (“Under the Blue Sky”) in 1959, followed by “The Wedding Day.”

Mr. Sen was often grouped with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak as foundational directors from the Bengal region who presented alternatives to Bollywood.

His 1970s films included three that became known as the Calcutta Trilogy (“Interview,” “Calcutta ’71” and “Padatik”), all exploring class struggle in that city. But by the end of the decade, his filmmaking had turned more reflective.

“Ek Din Pratidin” (“And Quiet Rolls the Dawn,” also known as “One Day Like Another”), which in 1980 became the first of Mr. Sen’s movies to play at Cannes, was about a woman who fails to return home from work one night, and the effects of the uncertainty on her family and others.

“I was pointing a finger at the enemy around us,” Mr. Sen said in a 2000 interview posted on Rediff .com, an Indian news site. “But from ‘Ek Din Pratidin,’ I began a journey of soul-searching. The process of fighting the enemy within began from there.”

In 1983 Mr. Sen won a jury prize at Cannes for “Kharij,” or “The Case Is Closed,” about the death of a servant boy in a middle-class household. The movie played at Film Forum in New York the next year.

“Mr. Sen avoids the material’s potential for easy irony, instead developing the story in a realistic and understated way,” Janet Maslin wrote in her review in The New York Times, adding that he “makes the death part of a complex social and economic structure that is not so easily addressed or changed.”

His later movies included “Genesis” (1986), about a weaver and a farmer who are living in relative isolation until a young woman enters their world and disrupts their lives. It was another quiet story with the larger meaning and issues only implied.

“Mr. Sen, who wrote the screenplay, keeps his characters down to earth,” Walter Goodman wrote in reviewing it in The Times. “They stand for human beings through the ages, unable to master either their own emotions or life’s circumstances. Now and then there is a frightening roar overhead, the sound of the world, that sends them cowering.”

His last movie, “Aamar Bhuvan” (“My Land”), was released in 2002.

Kunal Sen said he thought his father had special regard for his later works.

“He reached international fame during a phase when he made overly political films,” he said. “However, his later films were more introspective, and I think in general he was more proud of this later phase.”

Mr. Sen married Gita Shome, a theater and film actress, in 1953. She appeared in several of his movies under the name Gita Sen. She died in 2017. Mr. Sen’s son is his only immediate survivor.

In 1989 Mr. Sen made “Ek Din Achanak,” which, like “Ek Din Pratidin,” was about someone who doesn’t come home. He made reference to it in the Rediff interview when discussing his own career.

“I wish I could start from scratch,” he said. “I have done good, bad and indifferent films. I wish I could erase it all and start afresh like the professor in ‘Ek Din Achanak’ who walked out on his family on a rainy day and never came back. One of the characters in the film says, ‘The saddest thing with life is that you live only one life.’ ”

Achievements

Priyanka Dasgupta, December 31, 2018: The Times of India

Sen was the director of pathbreaking films such as ‘Padatik’ (The Guerrilla Fighter), ‘Akash Kusum’ (Up in the Clouds), ‘Calcutta 71’ and ‘Bhuvan Shome’, is survived by Chicago-based son Kunal and daughter-in-law Nisha.

Tributes poured in from luminaries as the film fraternity mourned the passing of an auteur of New Wave cinema who brought jump cuts, extremely fluid camera style and jerky editing techniques to Bengali and Indian films.

“Padatik summed up his attitude to life and work,” said film scholar Sanjay Mukhopadhyay. Sen, interestingly, would often call himself a “film-maker by accident”.

In death, Sen will remain ‘the Last of the Mohicans’

Born on May 14, 1923, Sen had shifted to Kolkata from Faridpur as a 16-year-old. Though he loved movies, financial compulsions forced him to take up a job of a medical representative till one day he gave it up when he had an epiphany in a Jhansi hotel room after having stripped naked in front of a mirror.

“I had called myself a b****** and made faces at myself for making a career out of selling medicines instead of having the courage to realise my dream of becoming a filmmaker. Then I sat and wept bitterly in front of the mirror. Despite being the blue-eyed boy of my bosses, I put in my papers two days later,” he had said in an interview to TOI.

His first film, ‘Raat-Bhor’ (1955), had Uttam Kumar in the cast. The film was a disaster and much later, Sen would wittily confess that with this film, he had a created a unique distinction for himself by having directed the biggest flop in Uttam Kumar’s career. Though he was completely down and out after this film’s release, singer Hemanta Mukhopadhyay spotted him in a footpath in Mumbai and agreed to produce his next titled ‘Neel Akasher Nichey’ (1958). But it was with ‘Baishey Shraban’ (1960) that Sen first got international exposure at the Venice and London film festivals.

‘Bhuvon Shome’ (1969) — with voiceover by Amitabh Bachchan — was both Sen and Utpal Dutt’s debut in Hindi cinema. Though national and international recognition followed, not everyone was impressed with the film. “One among them was Satyajit Ray. Earlier, after the making of ‘Akash Kusum’, Ray and Sen had engaged in a two-month-long war of words in the media. However, that didn’t create a dent in their relationship. Mrinal-da would always hold Ray in high esteem,” said film scholar Sanjay Mukhopadhyay.

From 1970 to 1975, Sen continued to churn out one film every year. If ‘Interview’ (1970) about a young job-seeker got Ranjit Mullick the Best Actor Award at Karlovy Vary, it had flattering follow-ups in ‘Kolkata 71’ (1972) and ‘Padatik’ (1973). His Left-wing orientation and continuous interest in making films that were overtly political shaped his cinematic voice in ‘Chorus’, ‘Ek Din Pratidin’ (1979), ‘Akaler Sadhane’ (1980), ‘Kharij’ (1982), ‘Khandhar’ (1983), ‘Genesis’ (1986), ‘Ek Din Achanak’ (1989), ‘Mahaprithivi’ (1991), ‘Antareen’ (1993) and finally, ‘Aamar Bhuvan’ (2002). By then, he was already in the process of shifting the gaze from looking at the enemy outside to the enemy within his own middle-class society. Awards from Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Moscow and Karlovy Vary saw a steady increase as did the offers to be an international festival jury alongside Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Gregory Peck.

What made him stand out was an uncompromising attitude. Director Buddhadeb Dasgupta said, “He never surrendered himself to any system — something so less seen among creative people today. I’ve seen how happily he lived in poverty during his struggle. That’s because he loved cinema.” Shreela Mazumdar, who made her debut in Sen’s movies , described Sen as a “bohemian cinemawallah”.

“He created a new language of cinema. . “He was the first in Indian cinema to use an unconventional narrative pattern. Some have even criticised him for borrowing western techniques, but I’d say Mrinal-da always kept his eyes and ears open,” said Dhritiman Chaterji. Describing him as a filmmaker who made socio-politically relevant cinema, director Goutam Ghose said Sen was always “looking for change”. “I wasn’t too impressed when I had first watched ‘Chorus’. It was only later that I understood that the film was way ahead of its time.”

After having made 27 films and five documentaries in Bengali, Oriya, Hindi and Telugu and having received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, Sen still took both praise and criticism in his stride. As he heard out his detractors, many of whom even questioned how the establishment funded his films even though they served as its critique, he believed they would never be indifferent to his cinema. At the end, he always wished to make each of them all over again. In life, he never wanted to talk about retirement since he was “always being born”. In death, he will remain the Last of the Mohicans.

Mrinal Sen, who along with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak formed the very disparate troika of film directors who brought global critical acclaim to Indian and Bengali films, passed away at his Bhowanipore home in 2018.

His cinema

From: December 31, 2018: The Times of India

From: December 31, 2018: The Times of India

See graphics:

Mrinal Sen’s cinema- Part I

Mrinal Sen’s cinema- Part II

Sharmistha Gooptu on Sen’s cinema

December 31, 2018: The Times of India

THE LONE RANGER OF NEW CINEMA, HARBINGER OF HARSHER REALITIES

Mrinal Sen ruptured the fabric of Bengali cinema. With ‘Interview’ (1970) and ‘Calcutta 71’ (1971), Bengali films acquired a form and language not seen before — it was political cinema which aimed not to entertain

I had met Mrinal Sen at an informal gathering in Chicago 2003, when I was a PhD student at the University of Chicago.

Then writing my dissertation, I had asked him if he would care to read one of the chapters, which focused on the first talkie era of the 1930s and early ’40s, and discussed cinema as a nationalist project.

He promptly agreed, and reverted the very next day. “I’ve read your chapter,” he said. “Why nationalism in cinema? Why impute that kind of a framework to cinema? Films are a language…for change.” While I did not fully agree with him, I understood where he was coming from. He was simply expressing what he truly believed in. That was Sen for me — single-minded, completely direct, committed and an activist in his own right.

Bengali cinema had many milestones before Sen. It was known for its literary qualities deriving from the genre of Sarat Chandra since the 1930s, iconic men and women like Pramathesh Barua, Uttam Kumar, Suchitra Sen or Kanan Devi, and Ray the master auteur, but had stayed largely a mirror of the bh adra , literature-loving, domesticated middle-class Bengali society.

Sen ruptured that fabric of Bengali cinema. With his films ‘Interview’ (1970) and ‘Calcutta 71’ (1971), Bengali films acquired a form and language not seen before — it was a political cinema which aimed not to entertain, but to show up social disparities and herald change.

Ritwik Ghatak had made his Partition trilogy in the ’60s, but Ghatak’s films arose from a personal angst and had pain, sadness and love, myths and music woven in with his politics. Sen was more forthright in his agendas, was not sentimental about hardship and used his cinema as a tool for marking political and social change.

Sen heralded the ‘New Cinema’ movement of the 1970s with his ‘Bhuvan Shome’ (1969). He worked with the most celebrated actors of this period — Smita Patil in ‘Akaler Shandhaney’ (1980), for which he won the Silver Bear at Berlin Film Festival, and Om Puri, Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah. His films contributed immensely in producing a national and international viewership for non-mainstream Indian cinema.

Sen belonged to the post-independence generation of Bengali filmmakers who worked at a time of increasing political and social flux, and he believed that cinema needed to be a part of that changing society. Sen’s films addressed the issues of unemployment and youth unrest.

‘Interview’ showed a day in the city of Calcutta — and one in the life of his lead character Ranju, a young man who has an interview letter from a reputable city firm and on that basis imagines a well-paid job, a newly decorated flat and a future with his modern girlfriend. The drama focuses on a suit which Ranju must wear to the interview to make the best impression. In the end, he appears for the interview not in the suit, but dressed in Bengali clothes, which puts paid to his chances of getting the job. It makes Ranju so angry that he finally cannot bear the sight of a suit-wearing mannequin in a fancy shop window, picks up a stone and shatters the glass. It was a representation of the Bengali youth who had turned back on the one-time colonial capital’s bureaucratic culture, and who became a political presence in Bengal during the turbulent years of the ’60s and ’70s.

It has been much less obvious that Sen was also a feminist, whose films had strong women protagonists, and who spoke in terms of women’s issues and women’s equality. In ‘Ek Din Pratidin’, Sen showed how a family dependent on the income of their office-going eldest daughter is thrown into a crisis when she fails to come home at the usual time one evening. It threw up the uncomfortable question of women’s control over their own income, and most importantly, the family’s claim to control the sexuality of an economically independent young woman.

Sen’s significant contribution to Bengali cinema remains that he was among the very first to create a body of films that dispensed with the romanticism and the ‘feel-good’ aesthetics of Bengali cinema, to give expression to harsher realities commensurate with contemporary history. His films did not have every Bengali swooning like over Uttam and Suchitra, but his contribution was equally paradigmatic. He showed the degeneration of the ‘middle-class’ bhadralok and the very basic instincts at play when it became a matter of human preservation.

In ‘Calcutta 71’, one of the three narratives had a mother — a widowed bhadramahila — almost egging on her teenaged daughter’s dalliances with young men because it brought in a few rupees. In Sen, Bengali films became fully faced with lived realities.

When Sen used Amitabh Bachchan’s voice

Shastri Ramachandaran, Amitabh was 'Bachcha' for Mrinal Sen, December 31, 2018: The Times of India

His serious and forbidding demeanour masked a raconteur. Iconic filmmaker Mrinal Sen could regale you with a good story when he chose to. Here's one about Amitabh Bachchan, when he was desperately seeking a break in films.

It happened in 1969, when the Big B was a "bachcha", as Mrinal-da said.

After shooting Bhuvan Shome in Bhavnagar (Gujarat), Sen was in Bombay editing the film. One day he went to the home of his friend KA Abbas the scriptwriter, who was working on Saath Hindustani. Abbas was surrounded by a group of people waiting to be cast in his film.

Sen told him that he was looking for a good voice, preferably a new voice, to be the narrator for his film.

A tall boy stepped out from among the assembled, saying "Ami Bangla jaaney" (I know Bengali). Sen told "the boy" his Bengali was bad but his voice good; good enough for a Hindi narration. Abbas let the boy take on the job.

Work done, Sen told the boy said he could not pay him much. The boy said he didn't do it for money. Sen, though, insisted and paid him. The boy asked if his name would appear in the titles. Sen nodded "Yes".

"In the title, put only Amitabh. Don't write Bachchan", the boy pleaded.

In the credits of Sen's Bhuvan Shome, the voice-over artiste's name "Amitabh" is the last one -- perhaps, the only film in which Bachchan's name figures at the end and not even in full. Seeing the film in the 1970s, I didn't notice this detail. Nor did I register the narrator's baritone voice - heard for less than five minutes at the film's beginning and end - that was to become famous.

On the last occasion I met Sen, in 2002 during a retrospective of his films in Delhi, he told me this story and asked me to pay attention to the voice.

Bhuvan Shome won many laurels, including the National Award in 1970. When the director and his voice-over artiste went to a film journalists' association function in Calcutta, seeing Amitabh, a reporter asked Sen, "Is he your next hero?" Sen liked the idea, "But I have to find a role that fits him". Amitabh himself was keen on acting in a film of Sen, who wanted to cast him in Interview. The problem was that Sen wanted an ordinary-looking person. "And Amitabh, even then, was a striking personality".

Sen assured me that "the boy" remembers all this. Some years ago Amitabh corrected a critic that the first voice-over he did was not in 1983 for Satyajit Ray's Shatranj ke Khiladi but for Bhuvan Shome. But, recalls Sen, "Amitabh says I paid him Rs 500. It was only 300. He does not remember".