Telephone interception (‘tapping’): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

1982-2021; British era

July 21, 2021: The Times of India

- In the 80s, President Giani Zail Singh feared many rooms in Rashtrapati Bhavan were bugged

- Ramakrishna Hegde’s government collapsed in Karnataka in 1988 following allegations of phone-tapping

- In 2006, Samajwadi Party leader Amar Singh alleged his phones were being tapped by the Delhi police

From intimidating looking men in spy movies climbing poles carrying telecom wires to listen into conversations, to sly software being loaded onto your phone without your knowledge, phone tapping has come a long way. While an Israeli software Pegasus has today become synonymous with bugged phones, phone tapping really is as old as the telecom history itself. Governments of all hues – both in Delhi and in state capitals — have snooped on their rivals and cops have, for decades, circumvented established norms to “keep track” of people of interest. Here’s a peek into the history of bugging in India:

How old is the history of phone tapping in India?

Phones were being tapped in India even before the Independence as is obvious from the laws that made it possible. ‘Lawful interception and monitoring’ is carried out in India by law enforcement agencies with the approval of the Competent Authority as per Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 read with Rule 419-A of the Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951 in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of the country, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence.

Can these agencies bug any phone they want?

No. All interceptions must be authorised by the Union secretary, home. In the states, the competent authority to clear tapping requests is the state home secretary. However, everybody knows that a lot of phone tapping happens under the radar. In every police force, there are officers with wherewithal to tap communications. Sachin Vaze, currently under arrest for staging a bomb threat to industrialist Mukesh Ambani, for instance, was one such officer with Mumbai police.

Section 69 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 empowers the Central government or a state government to intercept, monitor or decrypt any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource in the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of the country.

Politics, of course, is the hot ground of phone tapping July 2020 – Rajasthan political crisis: Congress leader Sachin Pilot and 18 Congress legislators rebelled against chief minister Ashok Gehlot. One of the accusations they levelled against Gehlot was that he had authorised tapping of their phones. The charges gained currency when audio clips of a telephonic conversation, allegedly between Union minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat and two Congress legislators, was shared by Gehlot’s officer on special duty (OSD) Lokesh Sharma. The audio clips were later handed over to the Rajasthan police’s Special Operations Group (SOG) to investigate charges that Shekhawat and some legislators were trying to topple an elected government. SOG eventually closed the case after a truce between Gehlot and Pilot mediated by the Congress central leadership.

August 2019 – Kumaraswamy sniffs a plot to pull him down: The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) probed illegal tapping of Karnataka politicians’ phones between August 1, 2018 and August 19, 2019. The report is still awaited. It was alleged the then chief minister H D Kumaraswamy ordered tapping of phones to keep track of several rebel MLAs. Kumaraswamy eventually lost power.

November 2019 – Chhattisgarh government restrained: The Supreme Court restrained the Chhattisgarh government from intercepting telephones of top police officer Mukesh Gupta and his family and granted him protection from arrest in the cases lodged against him. Mukesh Gupta was accused of unlawful phone tapping and violating the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act during the investigation of the civil supplies scam unearthed in 2015.

February 2013 – Arun Jaitley’s phone tapped: Delhi police constable Arvind Dabas was arrested on February 14 for allegedly trying to access Jaitley's call details. According to the police, Dabas used the official email ID of an Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) to send a request to a mobile service provider for the call detail records of the senior BJP leader. The police filed around a thousand pages of documents along with the charge sheet and named 36 persons as prosecution witnesses in the case.

February 2012 – AK Antony’s office bugged: A Military Intelligence (MI) officer found a monitoring device in the office of the then defence minister A K Antony. A high-level probe was initiated to look into the matter. The matter had come to light soon after the long-drawn battle between the Army and the Defence Ministry over the issue of General V K Singh's age.

June 2011 – Pranab Mukherjee’s office bugged: Pranab Mukherjee, then heading the finance ministry, wrote a letter to the prime minister asking him to conduct a secret inquiry into the bugging of his office. According to newspaper reports, Mukherjee suspected that one of his cabinet colleagues was responsible for the snooping.

September 2012 – Yashwant Sinha alleges phone tapping: Senior BJP leader alleged that his phone conversations were being illegally intercepted by the government after he accused Congress leaders of being involved in the Aircel-Maxis scam.

July 2011 – Lokayukta N Santosh Hegde’s phone tapped: Karnataka Congress sought the resignation of chief minister B S Yediyurappa over an alleged telephone tapping of Lokayukta N Santosh Hegde.

2010 – Congress accused of spying on allies: It was alleged that the ruling party used the latest phone-tapping technology to monitor and tape phone conversations of important leaders within the ruling alliance and some opposition leaders. According to an Outlook magazine report, among those whose phones were tapped were:

Sharad Pawar, NCP - Tapped in April 2010 while talking to IPL chief Lalit Modi

Prakash Karat, CPM -Tapped in July 2008 to understand opposition leaders’ strategy on the Indo-US nuclear deal

Nitish Kumar, JD-U - Tapped in October 2007 when he was using Bihar resident commissioner’s phone in Delhi

Digvijay Singh, Congress - Tapped in February 2007 while discussing with a Congress leader from Punjab candidates for the 2007 CWC elections.

November, 2009 – Mamata Banerjee’s phone tapped: Mukul Roy alleged that Banerjee's land phone and her mobile were being tapped and her house at Kalighat was under surveillance.

2006 – Amar Singh phone tapping case: Samajwadi Party general secretary Amar Singh claimed his phones were being tapped by the Delhi Police at the insistence of top Congress leaders.

August 1988 – In Karnataka, a phone-tapping accusation took a serious turn in 1988 as it led to the fall of then chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde’s government. A faction of the Janata Party led by Ramakrishna Hegde had merged with Jan Morcha of V P Singh to form the Janata Dal. Deve Gowda had remained with the Janata Party along with Ajit Singh. It was a conversation between Gowda and Singh that was tapped.

1982-1987 – President Giani Zail Singh fears bugging: Zail Singh suspected that several rooms in Rashtrapati Bhavan were bugged, presumably under the instructions of then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. And that is not all…

April 2010: Parliament was disrupted repeatedly as opposition leaders alleged that their phones were being tapped. In the Rajya Sabha, opposition BJP demanded setting up of a Joint Parliamentary Committee. Senior leader M Venkaiah Naidu demanded that the prime minister should make a statement.

An RTI application in December, 2018 revealed that 9,000 phones were tapped and 500 emails intercepted under the UPA government every month.

===Ten agencies authorised to intercept communication===

The competent authority in the Central government has authorised following ten agencies for this purpose:

1. Intelligence Bureau

2. Narcotics Control Bureau

3. Enforcement Directorate

4. Central Board of Direct Taxes

5. Directorate of Revenue Intelligence

6. Central Bureau of Investigation

7. National Investigation Agency

8. Cabinet Secretariat (RAW)

9. Directorate of Signal Intelligence (For service areas of Jammu & Kashmir, North East and Assam only)

10. Commissioner of Police, Delhi

2006-19

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Nov 4, 2019: The Times of India

From time immemorial, spying and snooping have been powerful tools. Even in democracies, those in power have used it, selectively and also brazenly, to pulverise competitors within their own party and against opponents by making public discomfiting details of secretly recorded private acts or conversations.

In January 2006, then powerful politician Amar Singh had moved the Supreme Court crying foul that his telephones were being snooped upon by government agencies. The SC had barred the media from publishing any leaks from the so-called telephone intercepts. In 2011, the SC dismissed the petition saying Singh had not come to the court with clean hands as he had suppressed several vital facts.

No one felt threatened by the then government’s action to snoop on a politician’s telephone. Probably, most privacy activists and politicians privately rejoiced at Singh’s telephones being intercepted and awaited possible titillating leaks from intercepting agencies.

In August 2008, the Congress-led UPA government authorised the tax department to intercept corporate lobbyist Nira Radia’s telephones for a period of 120 days, which was extended by another 120 days in May 2009. Portions of the Radia tapes were leaked to the media. These gave a glimpse of the lobbyist’s reach in politics, industry, high society, legal field and journalism. Leak of the tapes coincided with disclosures of the 2G spectrum scam and this strengthened the perception of ‘crony capitalism’ and fixing of government decisions.

Stung by revelation of his conversations with Radia, then Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata moved the SC blaming intercepting agencies for leaking the Radia tapes and sought a ban on publication of the contents, pleading that it violated his right to privacy. But an NGO, ‘Centre for Public Interest Litigation’, joined issue with Tata and sought a direction that all conversations in the Radia tapes be made public except those which were purely personal in nature.

The SC is yet to render a judgment on Tata’s petition, which has been pending since May 2010. When the court eventually decides this petition, it will confront a clash between right to privacy, which a nine-judge bench in K S Puttaswamy case ruled to be a fundamental right and part of right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution, and the right to information guaranteed under Article 19 as well as the RTI Act. The Radia tapes showed how journalists, who pontificate on everything, could be pliant when in the company of powerful politicians, socialites and lobbyists. A top national TV anchor was heard on the tapes attempting to play a political diva’s role in distribution of portfolios in the Manmohan Singh cabinet after UPA was re-elected in 2009. Another seasoned journalist was heard rather uncomfortably pleading with Radia to introduce his colleague, a woman journalist, into the lobbyist’s elite social circle that would help better her already fascinating curriculum vitae.

But the question remains – why did the intercepting agency not destroy Radia’s private conversations with numerous other illustrious personalities who had nothing to do with any dubious transaction or deal? If the agencies did not, then it was surely their duty to keep them in safe custody. Now, copies of all the 5,851 telephone intercepts of Radia, with their transcripts, are safely stored in the SC registry. Will it be made public some day when the court decides Tata’s petition?

After the Radia tape controversy, the government in 2012 put in place the ‘Lawful Interception and Monitoring’ (LIM) mechanism. In 2013, the same government proposed creation of a National Cyber Coordination Centre (NCCC), mandated to “collect, integrate and scan (internet) traffic data from different gateway routers of major internet service providers at a centralised location for analysis”.

All top government spy and technical agencies were made part of the proposed NCCC, which will give law enforcing agencies direct access to all internet accounts, be it your emails, blogs or social networking data. No rights activist perceived it as a threat to right to privacy.

On January 25 this year, the SC entertained a PIL by ‘People’s Union for Civil Liberties’ seeking judicial overview of the existing surveillance mechanism to ensure protection of citizens’ right to privacy. Citing data collected through RTI Act, the petitioner said, “In 2013 (during UPA regime), up to 9,000 orders for interception of phone calls were issued and in addition, about 500 orders were issued every month for interception of emails.”

It requested the SC to quash Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, Section 69 of the IT Act and Information Technology (Procedure for Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, passed under Section 69 of the IT Act.

Now, the WhatsApp revelation about spyware Pegasus snooping on politicians, rights activists, lawyers and journalists has brought us back to the Radia tape days. It is an enigma why the NDA government, which has sought a response from WhatsApp, has not come out with a categorical statement that it never used or authorised the use of this spyware by any of its agencies.

Will CPIL or PUCL file a PIL in the SC seeking details from WhatsApp for making public the conversations and text messages which were snooped upon by the spyware, as they did in Radia controversy?

The extent of the problem

2013: 9,000 phones, 500 emails intercepted each month

December 22, 2018: The Times of India

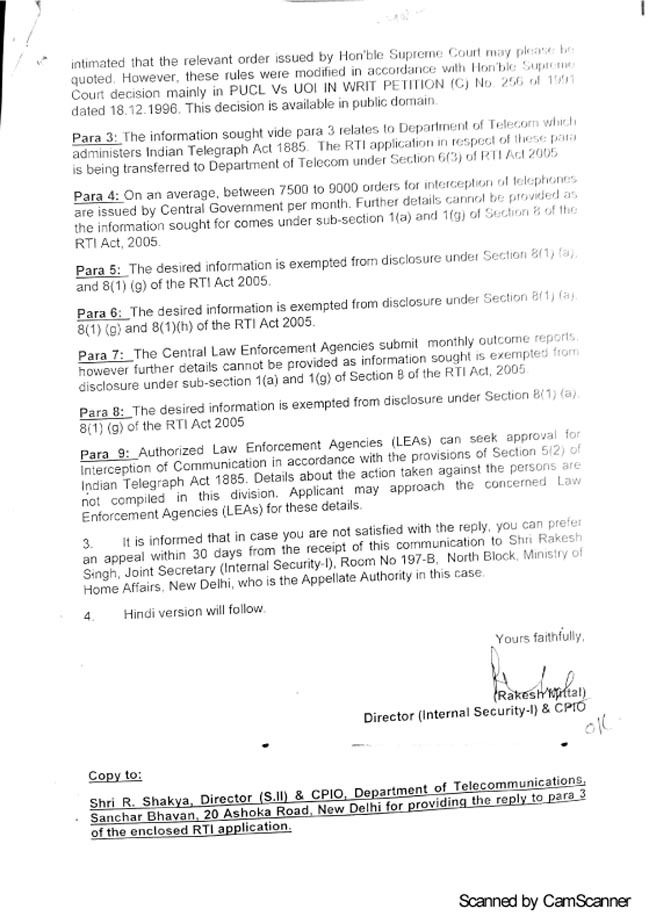

From: December 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: December 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: December 22, 2018: The Times of India

Amid controversy over the Modi government giving "snooping powers" to investigative agencies, a 2013 RTI reply reveals that around 7,500-9,000 phones and 300-500 email accounts were intercepted every month under the then UPA government.

The information was revealed by the ministry of home affairs in response to an RTI query filed by Prosenjit Mondal.

"On an average, between 7,500 to 9,000 orders for interception of telephones and 300 to 500 orders for interception of emails are issued by Central Government per month," the reply dated August 6, 2013 states.

The reply also discloses the list of ten central and state agencies that are authorised for lawful interception, which include Intelligence Bureau (IB), Narcotics Control Bureau, Enforcement Directorate (ED), Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI), Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), National Investigation Agency (NIA), Cabinet Secretariat (RAW) and the Commissioner of Police, Delhi.

Earlier today, the government reiterated that the notification on surveillance is a reiteration of the order that was amended by the UPA government in 2008, when A Raja was the minister of communication and information technology and Shivraj Patil was the home minister.

The clarification also added that the rules under Section 69 of IT Act [Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules] were framed in 2009, during the tenure of Raja and then home minister P Chidambaram.

It was in 2011 when the home ministry under Chidambaram issued the standard operating procedure (SOP) for interception, handling, use, copying, storage and destruction of messages, telephonic intercepts, emails under section 5(2) of Telegraph Act and Section 69 of IT Act, the statement adds.

Opposition parties on Friday had launched a scathing attack against the government for its move to authorise 10 Central agencies to intercept any information on computers, describing it as "unconstitutional and an assault on fundamental rights" and demanded its immediate withdrawal.

Defending the order, the government said the authorisation was given under 2009 rules and that the opposition was playing with the national security by "making a mountain where even a molehill doesn't exist".

2020: 7,000-8,000 permissions for interception given every month

Abhinav Garg, Sep 1, 2021: The Times of India

The Centre routinely grants 7,000-8,000 permissions for interception and monitoring of citizens every month, an NGO alleged before the Delhi HC.

Questioning the rigour behind the grant of such permission, the organisation, citing an RTI reply, told the HC that the committee that reviews such permission sits only once every two months.

While it sought the HC’s immediate intervention to verify under what due diligence is such permission being granted every month, a bench comprising Chief Justice D N Patel and Justice Jyoti Singh didn’t go into the specifics but asked the Centre to file a detailed response on the law and process being followed in such cases. “Time to file a detailed affidavit is granted to the Union of India. Point out in detail the law and procedure followed for monitoring and interception of phones,” the bench said, while posting the matter for the end of this month.

It is hearing petitions alleging “generalised surveillance” of citizens by the authorities and seeks a permanent independent oversight body, judicial or parliamentary, for the issuing and reviewing of lawful interception and monitoring orders/warrants under the enabling provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, and the Information Technology Act, 2000.

The petitions allege that citizens’ right to privacy is being “endangered” by surveillance programmes such as the Centralised Monitoring System (CMS), Network Traffic Analysis (Netra) and National Intelligence Grid (Natgrid).

The plea by the Centre for Public Interest Litigation and the Software Freedom Law Centre contends that these surveillance systems allow central and state law enforcement agencies to intercept and monitor all telecommunications in bulk, which is an infringement on an individual’s fundamental right to privacy.

Appearing for the NGOs, advocate Prashant Bhushan urged the court to intervene, pointing out that the government has admitted it places 7,000-8,000 interception requests every month with the committee, and that these are cleared. However, solicitor general Tushar Mehta asserted that all monitoring activities were being carried out as per law, and with requisite permissions, and opposed such “bald statements”. “This is not a public interest issue. Whatever we find to be significant (in the petition), we will reply. Other things we will ignore,” he told the court, seeking time to file the document.

In an earlier reply, the Centre said no blanket permission was granted to any agency for the interception or monitoring or decryption of any message or information under the three surveillance programmes — CMS, Netra and Natgrid.

The two societies have contended that under the existing legal framework there is an “insufficient oversight mechanism” to authorise and review interception and monitoring orders issued by state agencies. The petition has claimed that Netra is “essentially a massive dragnet surveillance system designed specifically to monitor the nation’s Internet networks, including voice-over-internet traffic passing through software programmes such as ‘Skype’ or ‘Google Talk’, besides write-ups in tweets, status updates, emails, instant messaging transcripts, Internet calls, blogs and forums.”

State-wise

Karnataka

Manu Aiyappa, July 23, 2021: The Times of India

Over the past two decades, all political camps and governments in Karnataka have been accused of phone tapping. This has prompted various allegations, rebuttals, inquiries and even high-profile resignations.

In most cases, it has been difficult to verify the contents or cast of characters in the alleged clips without a public admission. But political fireworks are guaranteed.

In the latest episode, Kateel, the state BJP president, has denied that the voice in the recording is his and has written to CM Yediyurappa, seeking a probe in the matter. However, this has not stopped speculations that a new CM is on the way in the state.

First line of defence

All controversies have two standard features. One, netas and parties concerned term the clip as fake, dismissing claims of wrongdoing. Two, any inquiry in such cases is often forgotten until a new leak surfaces.

Common themes

The themes include party infighting or churn, alleged horse-trading, abuse of power, improper conduct, claims of corruption and off-colour comments.

Here’s a list of some of the allegations involving those in high places in Karnataka politics.

The 1983 Moily tapes

This was the first major audiotape row in the state. It was alleged that Congress (I) member M Veerappa Moily could be heard on tape offering money to a legislator to ditch the Janata Party government headed by Ramakrishna Hegde.

The legislator was offered a bribe of Rs 2 lakh to defect to the Congress (I). Later, a commission of inquiry gave a clean chit to Moily.

HD Deve Gowda's phone tapping in 1988

In Karnataka, a phone-tapping accusation took a serious turn in 1988 as it led to the fall of the then chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde’s government. A faction of the Janata Party led by Ramakrishna Hegde had merged with Jan Morcha of VP Singh to form the Janata Dal. Deve Gowda had remained with the Janata Party along with Ajit Singh. It was a conversation between Gowda and Singh that was tapped.

When the issue was raised in Parliament, the then minister of communication Bir Bahadur Singh announced that nearly 50 phone numbers had been tapped in Karnataka and placed evidences, including orders signed to tap phones of Ramakrishna Hegde’s rivals in the party and outside.

Paid-seat claims in 2014

HD Kumaraswamy became embroiled in a row after an audio clip surfaced. It was alleged that the recording featured a conversation on money to be paid to JD (S) MLAs by an aspirant to the legislative council. Kumaraswamy rejected the charges.

Kumaraswamy, Yediyurappa pre-budget clash in 2019

Hours before presenting the state budget in 2019, HD Kumaraswamy released audio clips of alleged conversations involving the then state BJP state president BS Yediyurappa and a JD (S) MLA. The conversation allegedly took place between Yediyurappa and Sharan Gouda, son of Gurmitkal JD (S) MLA Naganagouda Kandakura. The MLA was being offered a ministerial berth and cash for switching sides. Yediyurappa strongly refuted the claims.

Kumaraswamy, Siddaramaiah phone hacked?

According to news reports, phone numbers of the then Karnataka deputy chief minister G Parameshwara and the personal secretaries of chief minister HD Kumaraswamy and former chief minister Siddaramaiah were hacked by Israeli spyware Pegasus in 2019.

Other controversies in Karnataka

Video that cost cabinet berth in 2016

Congress member HY Meti resigned as the excise minister after a video of his alleged relationship with a woman emerged online. A year later, the CID cleared him in the case, saying the video was doctored

Sex CD case in 2021

Earlier this year, an alleged video and a sex-for-job complaint forced Ramesh Jarkiholi to resign as the water resources minister. He has denied the claims and an SIT is looking into the matter. The high court is hearing petitions related to the case

Courts’ rulings

HC: ‘Tapping permissible only in emergency or for public safety’

Swati Deshpande, Oct 23, 2019: The Times of India

The Bombay high court quashed three orders passed by the Union home ministry to intercept phone calls of a businessman being probed by the CBI in a bribery case, saying it violates the right to privacy as held by the Supreme Court.

It directed the destruction of illegally intercepted conversations and, again quoting a Supreme Court order, said tapping can be allowed only in a public emergency or in the interest of public safety. A bench of Justices Ranjit More and N J Jamadar held that permitting illegal interception “would lead to manifest arbitrariness and would promote scant regard to the procedure and fundamental rights of citizens, and law laid down by the apex court”.

The HC order came in response to a petition by south Mumbai businessman Vinit Kumar against the three interception orders passed by the Union home ministry in October 2009, December and February 2010. The CBI had registered a case against him for giving a bribe of Rs 10 lakh to a bank official for credit-related favour. Making it clear that it was not going into the merits of the CBI allegations, the HC said: “The intercepted recordings stand eschewed from the consideration of trial court.”

The court found that the government took a varying stand, and said it “deprecated” such a stand, especially towards a fundamental right, and held that it drew an “adverse inference”.

‘Flouting of SC phone-tap rulings amounts to breeding contempt’

The Bombay high court further observed that if SC judgments and laws against such intercepts are permitted to be flouted, it may amount to “breeding contempt for law, that too, in matters involving infraction of the fundamental right of privacy under Article 21”.

The clause says no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty, except according to procedure established by law. Kumar’s plea was that the ministry’s sanction contravened the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, and urged that the recordings be destroyed as directed by the SC in the landmark People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) versus Union of India judgment of 1997. He also relied on a 2017 nine-judge Constitution bench judgment in the KS Puttaswamy case that speaks about fundamental freedom.

Quoting the PUCL case, Justice More said: “The expression Public Safety... means the state or condition of freedom from danger or risk for the people at large. When either of the two conditions is not in existence, it was impermissible to take resort to telephone tapping.”

SC directs Chhattisgarh: Stop phone tap of IPS officer, children

Oct 26, 2019: The Times of India

With allegations of phone-tapping of a senior police officer and his family by the Chhattisgarh government coming to its notice, the Supreme Court restrained the state from conducting such surveillance and sought an explanation.

Mahesh Gupta, who was DG of the state ACB and EOW in the previous BJP government, alleged that he is being “hounded” by the government in a 2001 suicide case in which he got a clean chit twice. But the state had gone ahead and reopened the case.

Senior advocate Mahesh Jethmalani, appearing for Gupta, told a bench of Justices Arun Mishra and S Ravindra Bhat that the state was tapping phones of the IPS officer’s two daughters, driver and a lawyer friend.

IPS officer trying to ride 2 horses at same time, SC told

He pleaded the court to stay the probe against the senior officer.

Senior advocate Mukul Rohatgi, appearing for the state, told the bench that the IPS officer filed a similar petition in the HC and the plea is pending there. “This is complete abuse of process of law. The HC has asked him to co-operate in the probe and he is trying to ride two horses at the same time by filing petition in HC and SC,” Rohatgi said.

Agreeing with his submission, the bench said it wouldn’t pass any order and it can allow Gupta to approach the HC but asked why his phones were being tapped. Rohatgi assured the court that tapping of Gupta’s phones would be stopped immediately if it was being done. He said he would respond why the tapping was done after instructions from the government. The hearing was posted for November 4.

Interestingly, the Bombay high court on Tuesday quashed three orders passed by the home ministry to intercept phone calls of a businessman being probed by the CBI in a bribery case, saying this violates the right to privacy as held by the SC. It directed destruction of illegally intercepted conversations and said tapping can be allowed only in a public emergency or in the interest of public safety.

Interception norms

As in 1999, 2007, 2014

The Times of India, Jun 18 2016

Interception norms amended thrice

A few years after the advent of mobile telephony in India, the Centre in 1999 amended the Indian Telegraph Rules to regulate and streamline interception of telephone calls and messages.

With service providers multiplying in different telecom zones, the Centre again amended the rules in March 2007.

After conversations of former lobbyist Niira Radia with politicians, bureaucrats, businessmen and journalists were leaked into the public domain and the Su preme Court expressed concern while dealing with a petition by Ratan Tata complaining of violation of right to privacy , the Centre amended the rules yet again in January 2014 to make the norms more stringent. The basic guidelines remained the same -order for interception could be issued by the home secretary in the Centre and states. In an emergency , such orders could be issued by a home ministry authorised joint secre tary-level officer.

In situations where such orders could not be obtained, the investigating officer could order interception provided this order was approved within 15 days. The 1999 amendment said an order of interception would remain valid for 90 days and was extendable up to 180 days. All interception orders were to be reviewed by a committee headed by the cabinet secretary (at the Centre) or chief secretary (at state level) within 60 days of commencement of interception to prevent misuse of power.

The 2007 amendment limi ted the period of interception to 60 days, extendable up to 180 days. For the first time, it talked about service providers designating two nodal officers who would be responsible for implementation of orders for interception of calls and messages. It reduced the period for approval for interception in emergency situations to seven days from 15 days provided in the 1999 amendment.

The 2014 amendment reduced the various approval periods, recognising that issues relating to interception had to be dealt with expeditiously to prevent misuse.

The laws, as in 2022

Deeptiman Tiwary, April 23, 2022: The Indian Express

How are phones tapped in India?

In the era of fixed-line phones, mechanical exchanges would link circuits together to route the audio signal from the call. When exchanges went digital, tapping was done through a computer. Today, when most conversations happen through mobile phones, authorities make a request to the service provider, which is bound by law to record the conversations on the given number and provide these in real time through a connected computer.

Who can tap phones?

In the states, police have the powers to tap phones. At the Centre, 10 agencies are authorised to do so: Intelligence Bureau, CBI, Enforcement Directorate, Narcotics Control Bureau, Central Board of Direct Taxes, Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, National Investigation Agency, R&AW, Directorate of Signal Intelligence, and the Delhi Police Commissioner. Tapping by any other agency would be considered illegal.

What laws govern this?

Phone tapping in India is governed by the The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.

Section 5(2) says that “on the occurrence of any public emergency, or in the interest of the public safety”, phone tapping can be done by the Centre or states if they are satisfied it is necessary in the interest of “public safety”, “sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence”.

There is an exception for the press: “press messages intended to be published in India of correspondents accredited to the Central Government or a State Government shall not be intercepted or detained, unless their transmission has been prohibited under this sub-section”. The competent authority must record reasons for tapping in writing.

Who authorises phone tapping?

Rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph (Amendment) Rules, 2007, says phone tapping orders “shall not be issued except by an order made by the Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of Home Affairs in the case of Government of India and by the Secretary to the State Government in-charge of the Home Department in the case of a State Government”. The order has to conveyed to the service provider in writing; only then can the tapping begin.

What happens in an emergency?

In unavoidable circumstances, such an order may be issued by an officer, not below the rank of a Joint Secretary to the Government of India, who has been authorised by the Union Home Secretary, or the State Home Secretary.

In remote areas or for operational reasons, if it is not feasible to get prior directions, a call can be intercepted with the prior approval of the head or the second senior-most officer of the authorised law enforcement agency at the central level, and by authorised officers, not below the rank of Inspector General of Police, at the state level.

The order has to be communicated within three days to the competent authority, who has to approve or disapprove it within seven working days. “If the confirmation from the competent authority is not received within the stipulated seven days, such interception shall cease,” the rule says.

For example, during the 26/11 attacks in Mumbai, the authorities had no time to follow the complete procedure, and so a mail was sent to the service provider by the Intelligence Bureau, and phones of terrorists were put under surveillance. “The proper procedure was followed later. Many times, in grave situations such as terror attacks, service providers are approached with even verbal requests, which they honour in the interest of the nation’s security,” an intelligence official said.

What are the checks against misuse?

The law is clear that interception must be ordered only if there is no other way of getting the information.

“While issuing directions under sub-rule (1) the officer shall consider possibility of acquiring the necessary information by other means and the directions under sub-rule (1) shall be issued only when it is not possible to acquire the information by any other reasonable means,” Rule 419A says.

The directions for interception remain in force, unless revoked earlier, for a period not exceeding 60 days. They may be renewed, but not beyond a total of 180 days.

Any order issued by the competent authority has to contain reasons, and a copy is to be forwarded to a review committee within seven working days. At the Centre, the committee is headed by the Cabinet Secretary with the Law and Telecom Secretaries as members. In states, it is headed by the Chief Secretary with the Law and Home Secretaries as members.

The committee is expected to meet at least once in two months to review all interception requests. “When the Review Committee is of the opinion that the directions are not in accordance with the provisions referred to above it may set aside the directions and orders for destruction of the copies of the intercepted message or class of messages,” the law says.

Under the rules, records pertaining to such directions shall be destroyed every six months unless these are, or are likely to be, required for functional requirements. Service providers too are required to destroy records pertaining to directions for interception within two months of discontinuance of the interception.

Is the process transparent?

There are multiple provisions aimed at keeping the process transparent.

Directions for interception are to specify the name and designation of the officer or the authority to whom the intercepted call is to be disclosed, and also specify that the use of intercepted call shall be subject to provisions of Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act.

The directions have to be conveyed to designated officers of the service providers in writing by an officer not below the rank of SP or Additional SP or equivalent. The officer is expected to maintain records with details of the intercepted call, the person whose message has been intercepted, the authority to whom the intercepted calls have been disclosed, date of destruction of copies etc.

The designated nodal officers of the service providers are supposed to issue acknowledgment letters to the security/law enforcement agency within two hours on receipt of an intimation. They are to forward every 15 days a list of interception authorisations received to the nodal officers of the security and law enforcement agencies for confirmation of authenticity.

“The service providers shall put in place adequate and effective internal checks to ensure that unauthorised interception of messages does not take place and extreme secrecy is maintained…,” the rule says.

It makes the service providers responsible for actions of their employees. In case of unauthorised interception, the service provider may be fined or even lose its licence.

The legal position

As in 2019

Nov 20, 2019: The Times of India

To Parl question, govt doesn’t spell out if it used Pegasus

Reiterates 10 Agencies Have Power To Snoop

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

New Delhi:

The Union home ministry on Tuesday declined a direct reply to DMK MP and former telecom minister Dayanidhi Maran’s query in Lok Sabha placed it on record that the government’s power to intercept phones and computer resources could only be exercised as per provisions of law, rules and SOPs. It also emphasised such powers were subject to proper safeguards and a review mechanism.

Citing Section 69 of the IT Act, 2000, minister of state for home G Kishan Reddy said the government was empowered to lawfully intercept, monitor or decrypt information stored or transmitted in any computer resource, in the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of India.

Minister of state for home G Kishan Reddy said government was empowered to lawfully intercept, monitor or decrypt information stored or transmitted in any computer resource, in the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states or public order. Similar, Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, empowered lawful interception of messages on occurrence of public emergency or in the interest of public safety.

“This power of interception is to be exercised as per provisions of law, rules and standard operating procedures. Each such case is approved by the Union home secretary in case of the central government, and by home secretary of the state concerned in case of a state government,” Reddy said, adding that 10 agencies had been authorised to carry out such interception.

The 10 agencies are Intelligence Bureau, Narcotics Control Bureau, Enforcement Directorate, CBDT, DRI, CBI, NIA, RAW, Directorate of Signal Intelligence (for service areas of J&K, northeast and Assam only), and commissioner of police, Delhi.

“Any interception or monitoring or decryption of any information from any computer resource can be done only by these authorised agencies as per due process of law, and subject to safeguards as provided in the rules and SOP,” Reddy said in a written reply to Maran’s query.

The Pegasus issue

Activists for SCs. STs and Israeli spyware

Abhijay Jha, Nov 1, 2019: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: Early October, human rights lawyer Shalini Gera was contacted by John Scott-Railton from Citizen Lab, Toronto University. “He told me that I was at digital risk and encouraged me to check up on his background,” said Gera, part of the legal team defending activist Sudha Bhardwaj, an accused in the Elgar Parishad case which allegedly led to the Bhima Koregaon violence.

Gera was told that Citizen Lab had a list of phone numbers which the research unit believed was targeted by the cutting-edge spyware Pegasus from February to May this year. “My number figured in that list,” she said. Pegasus has been developed by the Israeli firm, NSO Group.

The lawyer was asked if she had received any suspicious missed call on WhatsApp.

“In the timeframe he described, I had received several suspicious video calls from an international number in Sweden. I had not picked them up because I did not know anybody in Sweden. John told me it was not necessary for me to pick up the call for the phone to be infected. But the fact that they kept calling again and again shows that it perhaps didn’t work. At the end of May, I lost my phone. And there’s no way of checking whether it was infected or not. Had it been infected, John said, all the contents of my phone would have been accessible to those on the other side. It made me feel very vulnerable,” she said.

Gera is one of the 17 Indians whose phones were possibly infected by the frightening spyware, which had also been used to spy on the slain Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. All of them came to know of the possible breach from a call, a text message or an email from Citizen Lab, which had been approached by WhatsApp for help.

Most of these targets were either activists or human rights lawyers. Quite a few are defending those accused in the Elgar Parishad case. Others are tribal rights activists working in Chhattisgarh. Some are fighting cases against Dalit atrocities. A couple are journalists.

As per a 2016 price list, NSO Group charges its customers $650,000 (Rs 4.6 crore at current exchange rate) to hack 10 devices, in addition to an installation fee of $500,000 (Rs 3.5 crore), American business magazine Fast Company reported last year.

Nagpur lawyer Nihalsing Rathod, who represents several accused in Elgar Parishad case, told TOI that he had filed a complaint with WhatsApp in March but got a reply only earlier this month. “The first doubt came in March this year and I immediately alerted WhatsApp that my data is being breached due to some malware. They failed to respond at that time but Citizen Lab confirmed my doubts,” said Rathod who also represents Delhi University professor G N Saibaba, alleged to have Maoist links.

On being asked why he could be in the list, Saroj Giri said, “Everything I do is there in the public domain, we need to question the government. The government is acting very innocent right now but I am sure this has taken place at the highest level.” An assistant DU professor of political science, Giri is also part of the committee for the defense of Saibaba, who is now in a Maharashtra jail.

Gera, also secretary of People’s Union for Civil Liberties' Chhattisgarh unit, says that John had told her that the software costs millions of dollars. “It’s not something anyone can use. Only governments can afford to have this kind of software,” she said.

Chhattisgarh-based rights activists Bela Bhatia and Degree Prasad Chouhan — who were also objects of snooping — have described the attempt as a “severe intrusion of privacy.” Bhatia has been raising incidents of human rights violations in Maoist-affected Bastar. Chhattisgarh PUCL’s president Degree Prasad Chauhan feels government agencies could be involved in this surveillance that “breached his privacy by accessing his social media messages and updates”.

Former BBC journalist Shubhranshu Choudhary, who has been working as a peace activist in strife-torn Bastar, said he strengthened his cyber security after being informed by Citizen Lab about a month ago. “I have no idea why I am being targeted. Perhaps we are being watched closely because we are working as peace activists and trying to settle people who are displaced from Bastar,” he said.

Siddhant Sibal, defence and diplomatic correspondent, WION television channel, said he was asked to change the passwords of all his social media accounts.

Pegasus attacked 121 in India, breached 20

Rajeev Deshpande, Nov 23, 2019: The Times of India

The use of Pegasus ‘snoopware’ was successful on 20 of the 121 WhatsApp users in India whose mobile phones were targeted by the remote surveillance software made by Israelbased cyber tech firm, NSO, the Facebook-owned messaging platform has told the government.

WhatsApp, in a response to a request for technical information, said that it was unable to conclusively determine what data, if any, was accessed on the devices of the targeted users.

The intrusion was intended to mine stored information and data and communications on mobiles.

In its latest communication to the government on November 18, the messaging platform said the attack on users was of a high order of complexity and sophistication. “(Due to) WhatsApp’s limited visibility into certain aspects of the attack, WhatsApp’s investigations into the attack are ongoing,” the company said.

‘Most of Pegasus’s 1,400 victims across the world were activists’

In information also shared with a parliamentary committee, the government noted that WhatsApp said, “121 users is where the attempts were made while 20 users is where the attempt seems to have been successful”. The users were warned on October 29 about the attacks.

In September, WhatsApp told the government it was reviewing information even as the full extent of the attack may never be known. It had hinted that data of 20 users might have been compromised, but confirmed this definitively in its November 18 communication.

However, in a communication in May, WhatsApp had not seen the Pegasus software as a potent threat. WhatsApp had then told the government, “We believe that a select number of individuals were targeted — this is not a security incident that would have affected a large number of users”.

With reports saying activists with an anti-government bent and some journalists were targeted, WhatsApp has indicated that most of Pegasus’s intended victims globally (about 1,400) were also largely activists. The platform said it offered support to “members of civil society globally targeted by the attack”.

It did so in coordination with Canada-based Citizen Lab which contacted users who had received a “special WhatsApp message”. In May, WhatsApp told India’s cyber security agency CERT-In that it had identified and promptly fixed a vulnerability that would help attackers execute a code on mobiles.

The platform was also asked about a media report on May 15 that a cheap software might enable users to overcome WhatsApp controls. The firm said action had been taken to remove “WhatsApp clones”.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2016: changes

Tough regime to check phone tapping

The Times of India June

Tapping phone conversations are no longer an easy task with the government putting in place a tough regime to check against possible misuse of powers. Telecom company executives said that only a handful of agencies are authorised to tap conversations and even that has to be authorised by the home secretary. Given the possibility of facing strict punitive action, telecom companies said, the nodal officer in each company ensures that there is no unauthorised access and even the conversation that is recorded is available only to the agency concerned. “There is a log that is maintained and anyone who logs into the server can be tracked. The information is not available internally and only the phone number is available,“ said an executive.

2016: Revised norms

The Times of India, August 4, 2016

Norms on phone tapping revised

The government told Rajya Sabha that guidelines have been revised to curb illegal phone snooping and to tighten the process of obtaining telephone call data records (CDRs) of MPs and other citizens. Acoording to the revised guidelines, head of the police organisation's permission is required for obtaining CDRs of MPs.

2018: changes

Data interception order sparks row, govt cites 2009 UPA rules

Bharti Jain, December 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: Bharti Jain, December 22, 2018: The Times of India

10 Agencies Can Snoop On Phones And Computers

The Centre’s notification designating 10 intelligence, tax and law enforcement agencies to intercept and decrypt information in

computers kicked off a political storm on Friday with the opposition accusing the government of snooping and the latter clarifying that the rules actually tightened loopholes in the law.

The opposition alleged that the agencies had been armed with powers to monitor any computer.

The government soon launched a counter-offensive, arguing that the notification was derived from rules framed under the UPA in 2009 and, contrary to charges, the Centre had made the interception regime more precise and less vulnerable to abuse by specifying the agencies which could do so.

‘Must cite reason to decrypt messages’

It also said every case of interception would continue to require permission from the home secretary and review by a panel headed by the cabinet secretary. It added that while seeking permission, the agency concerned would have to specify one of the five grounds on which they could decrypt messages on electronic devices.

The five grounds are — “in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of the country; defence of India; security of the state; friendly relations with foreign states; public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence relating to above”.

Apart from the heated politics, before the home ministry order notified on Thursday, every request for interception of information on a computer — emails, chat messages and even drafts on smartphones, tablets and laptops — had to be handled and authorised by the home secretary or state-level competent authority.

Now, the order will allow only the designated agencies — IB, Narcotics Control Bureau, ED, CBDT, DRI, CBI, Cabinet Secretariat (RAW), NIA, Directorate of Signal Intelligence and Delhi Police commissioner — to carry out interception, monitoring and decryption of any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in a computer resource under the Information Technology Act, 2000.

It is only in emergent situations that a designated agency can approach a service provider and seek access, but it will need to notify the home secretary in three days. In case there is no post-facto approval in seven days, the interception will have to stop. Each interception request relating to computers will require prior approval of the home secretary/state government. By passing the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, the UPA government said only authorised agencies should carry out surveillance but did not notify these agencies.

A total surveillance system?

Cybersecurity Experts, Lawyers Red Flag ‘Power To Snoop’

Cyber security experts, lawyers and activists have raised serious concerns over the Union ministry of home affairs (MHA) order that gives 10 investigating agencies the power to “snoop” into citizens’ digital space.

Executive director of Internet Freedom Foundation Apar Gupta said the recent order will lead to “a complete surveillance system” without any options for safeguards as it is impossible to exist without leaving a digital footprint nowadays.

“The constitutional standing for privacy has become stronger after the Supreme Court’s Aadhaar judgment in 2017. Section 69 was framed nearly a decade ago, so it did not conform to the same standards of privacy. The government cannot use it as grounds to cannot go snooping around without judicial sanctions,” said Gupta.

Prasanth Sugathan, legal director of Software Freedom Law Center, an NGO that supports digital rights across the globe, also called the order an attempt at “digital tapping”, but highlighted that it is only a part of the problem. “Our concern should not be limited to just these 10 agencies. Section 69 should be struck down completely because it lacks judicial oversight. It works at the executive level alone,” he said, adding the “entire surveillance system supported by the state is a problem.” On Twitter, too, several lawyers criticised the order as unconstitutional and a violation of individual freedom. “This is a gross violation of SC judgments, including Shreya Singhal. This is void for vagueness since the expression ‘any information’ could cover anything from our Facebook profiles to WhatsApp messages, to Twitter, it is being challenged as surveillance,” tweeted SC lawyer Indira Jaising. Shreya Singhal v. Union of India is a 2015 Supreme Court judgment on online speech and intermediary liability.

Delhi Police: Special Cell project

Techtonic shift in phone tapping?, Feb 8, 2017: The Times of India

Secret Project, In Final Stages, Will Help Special Cell Overhear 120 Calls Simultaneously

In a major revamp of the way it eavesdrops on phone chatter, the Special Cell of Delhi Police, which primarily deals terror cases, is enhancing its call interception system. Officers have confirmed that the highly secretive project is being executed on a priority and the force is in the final stages of the process to procure advanced law enforcement monitoring facilities (LEMF).

The new LEMF will allow the cops to overhear 120 calls simultaneously , sources said.What is being set up is not just a central monitoring system, but an entire network of aro und 100 computers and highspeed servers, equipped with powerful 128GB DDR4 RAMs.These are expected to run up bill running into crores of rupees, officers privy to the plans confirmed.

The New Delhi range of the Special Cell will get a major portion of the acquisitions with 36 computers and servers. The south-western and northern ranges, which focus on organised crimes, will get 20 each, while the southern range will bag 15. A set-up of five computers and the central server will be installed at Police Headquarters and will be overseen by the DCP (Special Cell).

However, though a central monitoring system is expected to check any misuse of the facility, it is unclear if the Union ministry of home affairs has given the project a goahead. Last year, it had objected to the increasing demands for interception approval made by Delhi Police and sought a detailed actiontaken report on the hundreds of numbers that it had approved in a six-month period.

Under the phone-call intercept protocol, the Delhi Police commissioner, DGPs of states, and eight other agencies -Intelligence Bureau, Research & Analysis Wing, Narcotics Control Bureau, Central Bureau of Investigation, National Investi gation Agency , military intelligence of the defence ministry and the Central Board of Direct Taxes are authorised to intercept calls with the prior approval of the home ministry .

The Special Cell is the nodal agency in Delhi for call interceptions. It can give extensions upon approval to police stations. On average, the union home ministry okays around 5,000 requests made by these agencies.

In 2014, the government notified a fresh set of procedures for legal interception of calls under Section 5 (2) of the Indian telegraph Act. However, rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph Rules allows for lawful interception of phones without prior approval under unavoidable circumstances. However, such interceptions have to be approved within seven days.

Lawful interception of calls aids enforcement agencies in obtaining network communications in a clandestine manner. The intercepted data, called handover interfaces, is categorised in three levels, with the one codenamed HI3 being the most critical, an officer explained, because it contains the content of the intercepted communication and can be used by law enforcement agencies as leads or evidence against a suspect.