The Meitei: Religion

This article is an extract from THE MEITHEIS T. C. HODSON Late Assistant Political Agent In Manipur And Superintendent Of The State Fellow Of The Royal Anthropological Institute With An Introduction By SIR CHARLES J. LYALL K.C.S.I., C.I.E., LL.D., M.A. Published under the orders of the Government of Gastern Bengal and Assam Illustrated LONDON David Nutt 57, 59, Long Acre 1908 Indpaedia is an archive. It neither agrees nor disagrees |

Contents |

Nature Of Popular Beliefs

Would that it were possible to imitate or transcend the easy brevity of Father Sangermano, who declares that the people of Cassay worship the basil and other plants after the manner of the ancient Egyptians.* Here we have the stately fabric of Hinduism with its elastic ease of accommodation, we have the fresh, healthy, indigenous system of animism, and as a result of the commingling of these forces at this point a medley of religious beliefs in which every phase of human imagination finds its place.

Hinduism is of comparatively recent origin, though the records of the Brahmin families in Manipur claim in some oases that the founder of the family settled in the valley at so remote a date as the middle of the fifteenth century. To the royal will of Pamheiba, the monarch in whose reign the fortunes of the State reached their zenith, Hinduism owes its present position as the official religion of the State. At first the decrees of the king received but little obedience, and the opposition to the change centred mainly round the numerous members of the royal family who were supported, not un- naturally, by the nmihas, the priests of the older religion. Eeligious dissent was treated with the same ruthless severity as was meted out to political opponents, and wholesale banish- ments and execution drove the people into acceptance of the tenets of Hinduism. As a matter of fact the long reign of Chandra Kirti Singh witnessed the consolidation of Hinduism which had lost much of its hold on the people during the sad times of the Burmese occupation. Gambhir Singh once ordered a Brahmin who had failed to take due and proper charge of a pet goose which had been entrusted to his care, to eat the bird which had died from neglect,* but in his son's time such an order was impossible.

The old order of things has not passed away by any means, and the maiba, the doctor and priest of the animistic system, still finds a livelihood despite the competition on the one hanti of the Bralmiin, and the Hospital Assistant on the other.

It is possible to discover at least four definite orders of spiritual beings who have crystallized out from the amorphous mass of animistic Deities. There are the Lam Lai, gods of the country-side who shade off into Nature Gods controlling the rain, the primal necessity of an agricultural community ; the umang Lai or Deities of the Forest Jungle; the Imug Lai the Household Deities, Lords of the lives, the births and the deaths of individuals, and there are Tribal Arieestors, the ritual of whose worship is a strange compound of magic and Nature- worship. Beyond these Divine Beings, who posaetts in some sort a majesty of orderly decent behaviour, there are spirits of the mountain passes, spirits of the lakes and rivers, vampires.f and all the horrid legion of witchcraft. Quot homines, tot daemones, with a surplusage of familiars who serve those fortunate few who are recognized as initiate into the mysteries.

It is not sound to regard these beliefs as "survivals'* despite the official superstratum of Hinduism which exists in Manipur, solely in its exoteric form, without any of the subtle metaphysical doctrines which have been elaborated by the masters of esoteric Hinduism. The adherence of the people to the Yaishnavite doctrines which originated in Bengal, is maintained by the constant intercourse with the leaders of that community at Nadia. It is difficult to estimate the precise effect of Hinduism on the civilization of the people, for to the outward observer they seem to have adopted only the festivals, the outward ritual, the caste marks, and the exclusiveness of Hinduism, while all unmindful of its spirit and inward essentials. Colonel McCulloch remarked nearly fifty years ago that, " In fact their observances are only for

Hing-cha-bi (hing = living, cha = to eat, bi = honorific or respectful suffix), that which eats living persons. appearance' sake, not the promptings of the heart,"* and his criticism seems as true now as when it was written. It is, perhaps, too early to predict the influence of British rule upon the religious ideas of the people. The Penal Code is in some aspects a code of morality resting in native view on superior force rather than on divine authority or intrinsic virtue. The inevitable rise in morality which ensues from security of life and property, from increasing wealth, and from a greater range of needs, is slowly becoming evident in Manipur, and must sooner or later exert an influence on the religious life of the country. The maibas frequently adapt their methods to the altered circumstances in which they now find themselves, and realize that the combination of croton oil and a charm is more efficacious than the charm alone. It is too much to expect them to give up the charm all at once.t

In Manipur where Hinduism is a mark of respectability, it is never safe to rely on what men tell of their religion ; the only test is to ascertain what they do, and by this test we are justified in holding them to be still animists.

It is curious to note the complete absence of any traces of Buddhism in Manipur, although it is reasonably certain that in historic times there has been a steady flow of intercourse with Buddhistic Burma. The Shans under Samlongpha who invaded Manipur in the beginning of the fifteenth century seem to have left no trace of their occupation of the State upon the religious belief of the people, for the records distinctly show that up to the formal introduction of Hinduism in the reign of Pamheiba the people buried their dead, ate meat, drank ardent spirits, and behaved just like the hill people of the present day. There is not a sign of contact with the lofty moral doctrines of Buddhism.

The Chronicles enable us to know the names, and in some cases also the functions, of a few of the popular Deities. Thus Panthoibi, to whose service Brahmins were appointed by Pam- heiba (Gharib Nawaz), is said to be the wife of Khaba, probably the divine ancestor of the Khaba tribe, and to be the Deity of birth and death. She is certainly connected with the worship

Cf. Sir A. Lyall, Asiatic Studies, vol. i. p. 113, Lord Avebury, Origin of Civilization. of the sun. The worship of Sena Mehi by a prince was regarded as a sure preliminary to an attempt by the worshipper on the throne, and was reserved for the Raja alone. The Deity Lairema is associated with oneiromancy, and is also the name given to private Deities. Of her magical nature there can be no doubt, for the Chronicles state that on the 17th Langhon (September), 1853, " There was a great fuss about lirema Hooidompokpi A sepoy reported to the Maharajah, that since Khuraijam established his God, Hooidompokpi, a considerable number of men died. The number of widowers and widows increased. The Maharajah ordered Losang Ningthou and Nongthonba to cause inquiry into this. It was turned out that there were two Liremas." Of the Deity named Noongshaba we know that he is associated with a stone, and is probably, as his name would show (nong = stone, and shaha = maker, lit. maker of stones), the Deity of Creation of the rocks and stones. We do not know the reason why he, or Yumthai Lai, the Deity whom, on linguistic grounds, we may believe to be the establisher of houses, or the Deity Taibong Khombi, She who makes the earth to swell, should have been allowed to be served by Brahmins, while Pamheiba disestablished such Deities as Taibongkhaiba, He who divides the earth, or the clan Gods, or such Goddesses as Waihaiba. We know that Seua-mehi and Laima-ren are connected, and the name of the latter seems to mean " The Great Princess." * We may conjecture that the female Deity Laishing-choubi was the wife of Laiching, the Deity whose abode is on the hill of that name. Of others, such as Wangpurel, Pu- thiba, Pukshore, Yumnam Lairema, Sarangthem Lamabi, Laisangthem Lamabi, we know little beyond the mere names. Some of them may be purely local, and their worship con- fined to the members of one family, or of one house, but even if nomina only, they are also numina, and rank above the vast crowd of hingchahis or vampires (king = alive, cha = to eat, that which eats live men), lais hdlois, or demons, in which the people believe and, fear being the basis of their ritual, which they try to propitiate. Colonel McCulloch states that there

- Laima = princess, and ren or len = great, a word not now found in

Meithei but common in Thado, and also found in turen = great water or river, from ttii * water, and khul-len = big or parent village, from khtU = village. were three hundred such deities, and that they "are still propitiated by appropriate sacrifices of things abhorrent to real Hindoos*

Competent ethnologists declare that the conception of divine beings as " Gods " connotes, firstly, the relationship of members of a family, subject to one head, who may be Lord of all, or attenuated as merely primus intm' pares ; secondly, their repre- sentation in human form; thirdly, the association of moral snefit with their worship; fourthly, their presentation as lealized human beings; and, fifthly, their occupation of a "definite place in a definite cosmogonic system. Practically all lese characteristics are lacking in Manipiu'. Indeed, it seems be clear that deities like Panthoibi, Yumthai Lai, Laimaren, "and Sena-mehi, are merely names of class spirits, for every householder is virtually the priest of these Deities, just as in ancient Rome every household had its Vesta. There are images of deities hewn from stone, but the more powerful Deities, if we except Govindji, the God of the Eoyal family, are represented by rough stones, which Manipuris regai^l not exactly as the image of the Deity, but as his abode.

The Worship of Ancestors

If the definition of ancestor-worship is strictly narrowed, we have in Manipur, among the Meithei only, the form of ancestor worship which is practised by all Hindus, but if it be enlarged, as in the circumstances it ought to be, we find several curious phenomena to which attention should be given.

The worship of the clans which, seven in number, compose the Meithei nation or confederacy, clearly consists in the adoration and propitiation of the eponymous ancestors of the clan. The name of the tribal Deities is given as Luang pokpa, or ancestor of the Luangs, Khuman pokpa, ancestor of the lOiumans, apparent exceptions to this being the tribal Deities of the Ningthaja and Angom clans, which are called Kongpok Ningthou, or the King of the East,J alias Pakhangba, whom we know from other sources to be the reputed ancestor of the clan in question (the Ningthaja), and Purairomba. The aliases of the other tribal Deities are Poiraiton, for the Luangs ; Kham- dingou, for the Khabananbas, Thangaren, for the khumans and Ngangningsing, for the Moirangs ; and Nungaoyumthangba, for the Chengleis.

The Hindu friends of the people have discovered for them a respectable genealogy by which they are descended from the Guru, the sage who is Lord of the Universe (taibangpanbagi mapu), but the accounts differ. In the version collected by me from the lips of a Manipuri, who had been a sellungba, or court officer, the Angdms spring from the brain of the sage, the Luangs from between his eyes, the Ehabananbas from his eye, the Moirangs from his nostril, the Chenglei from his nose, the Kumul from his liver, and the Ningthaja from his spleen. The account prepared for me by a very respectable Bengali clerk, states that the Ningthaja were bom from his left eye, the Angom from his right eye, the Chenglei from his right ear, the Khabananba from his left ear, the Luang from his right nostril, the Kumul from his left nostril, and the Moirang from his teeth. It is a delicate matter to assign a preference to one version rather than the other, but the symmetry of the second version is apt to excite the suspicion that the orthodoxy of the reporter may have misled him.

In the case of the ancestor of the Ningthaja clan, Pakhangba, we have the curious superstition that he still sometimes appears to men, but in the form of a snake, which reminds one of the Zulu belief that their ancestors assume the shapes of harmless brown snakes. Another instance which may help to explain the Pakhangba worship is afforded by the classical instance of the Romans, who held that the " genius " of every man resided in a serpent. Cicero (De Divinatione, i. 18, 36), tells how the death of the serpent, which was the genius of the Father of the Gracchi, presaged, and was soon followed by, the death of Tiberius. Eecent investigations prove that the genius was the " external soul " so familiar in the folk tales of primitive peoples. Here the snake is the external soul of the Raja, the piba of the Ningthaja clan, and the head of the Meitheis.* Speaking

- See also Miss Jane Harrison, Prolegamena to Greek Religion, pp.

327-332. Jevons of the religion of the people, Colonel Mcculloch* says that " The Raja's peculiar god is a species of snake called Pakung-ba, from which the Royal family claims descent. When it appears it is coaxed on to a cushion by the priestess in attendance, who then performs certain ceremonies to please it. This snake appears, they say, sometimes of great size, and when he does so it is indicative of his being displeased with something. But as long as he remains of diminutive form it is a sign that he is in good humour."

Whether connected immediately, or only remotely, with these associations of ancestor worship, I cannot say, but it is at least noteworthy that in the hymn which is adckessed to the Raja by the man who is taking the sins of the country upon himself for the comming year, the Raja is addressed as " Great Grod Pakhangba." This may, of course, be merely an honorific phrase in harmony with the extravagant language used to the Raja, who on all occasions is addressed as if he were indeed a Deity incarnate.

In contrasting the Meithei belief in Pakhangba with the Khasi faith in U Thlen, a clear account of which is given by Major Gurdon,t the author of the monograph on the Khasis and General Editor of this series, several points of interest issue to notice at once. Pakhangba is an ancestral spirit worshipped by women, while among the matriarchal Khasis, where women are priests, U Thlen is not regarded apparently as an ancestor. Both are associated with the fortune of the family, but while U Thlen may move from one family to another, Pakhangba is associated only with the Raja directly, but indirectly with the whole State. Both vary in size, and it is noteworthy that the occasions when they assume their largest and most monstrous form, practically signify much the same thing, viz. portents of evil and misfortune. I have no evidence of human sacrifices to Pakhangba.

In regard to the means adopted to get rid of the thleriy we may compare the transfer of sin by passing on the royal clothing with the sacri- fice of property, money and ornaments which khasis make when endeavouring to free themselves of the snake.

By the side of the road from Cachar not more than a mile from Bishenpar, are two small black stones which are reputed to be Laiphams, or places in which abides a Lai,' a being whose exact equivalency is difficult of determination* At

Hiyangthang, about six miles distance from Imphal, is a temple of considerable fame, for here abides the Hindu Groddess Durga, who is known to have avenged an insult to her shrine by causing the death of the sacrilegious. In this temple is a rough black stone which naturally I was not allowed to see close at hand, but which, so fiEur as I could distinguish it, was entirely unwrought. This was the laipham of the dread Goddess.

One of the last civil cases that came to my notice was a dispute about an ammonite of immense sanctity. In the course of the evidence it was proved that it had been looted from the Cachar Sajas at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and passed into the possession of Grambhir Singh, upon whose death it came into the hands of his widow, mother of Chandra Kirti Singh, who took it with her, when, after the attempted assassination of Nur Singh, she fled to Sylhet.

The stone was quite small, and its curious markings showed to all but the densest eyes that it was a thing of high sanctity. It brought good fortune to its possessor, and in the disturbances of 1891 was seized by Angao Sena, brother of the Baja» who was sent to the Andamans, and who gave it to a Brahmin who sold it to a Bengali, when it was rediscovered and claimed by the heirs of Sur Chandra, who alleged that as it had always been kept in the bari of the Royal Family, it was distinct from the regalia, and by the representatives of the present Baja, who asserted that it was impartible property attached to the office of Raja, while the Bengali claimed it for value had and received.

I forget the finding of the learned Court on the case. In pre- Hindu times, as mentioned in the Chronicles, the worship of stones — perhaps as laipham — was regularly practised, and the luck of the State was symbolized by the great Nongaha or animals of the Sun which, built of masonry to resemble stone, guarded the Kangla. In the Chronicles we read that stones were looted from defeated Naga villages and brought down to Imphal. Now, at Maikel or Mekrimi, is a stone which, jealously guarded by the khullakpa, has great virtue in giving strength to warriors, and upon which no woman may look. I have heard it said in Manipur that it is worse by far to he reputed to be rich than to he rich, and the possession of so coveted an object as a war stone without doubt encouraged aggression and attack.

Lois worship Sena Mehi, and Laimaren the Imung Lai, and offer up pigs, dogs, ducks and fowls to them. The Sun God is worsliipped by the people of Fayeng Loi in Sajibu (April), when they offer up a white fowl and a white pigeon* At Andro Loi, offerings are made to both Sun and Moon, the latter being worshipped every month on an auspicious day in the last quarter of the moon. They offer up each year a pig in honour of the Umang Lai or Deities, who control the prosperity of the crops, as Hain and weather Gods. Pan am Ningthou and Purairomba are their Umang Lai, while Khabru is the Umang Lai of Fayeng, and of Sengmai, where they told me he was the Lam Lai or God of the country side.

They also worship the Clan God, whose namea coincide with those of the Clan Gods of certain Meithei clans. Fayeng Lois assert that their ancestors were Meng-khong-ba and Hameng-mitpa.*

Religious Rites And Ceremonies

Colonel Mcculloch states tliat "The Dussera, or as it is called in Munnipore Kwaktalba, is the principal festival in- troduced with Hinduism. At it the tributaries lay presents before the Raja and renew their engagements of submission. Honorary dresses, plumes of feathers, and other baubles which are highly prized, are distributed to persons who, during the past year, may have distinguished themselves, or to others who, at some former period, had done so, but whose merit had passed unrewarded." Kivdktalba seems to mean the chasing of the crow (from kwak = a crow, and tanha = to chase or pursue). The Holi attracts a gay crowd of women to the capital who are seldom slow to take due advantage of the licence permitted to them, but from the coincidence of so many animistic or other festivals with those of Hinduism, a phenomenon which admits of an easy explanation, it is perhaps wiser to say that attention is paid to all and each of the various festivals which

• Meng-khong-ba = cat-voiced and Hameng-mitpa = goat-eyed. are observed by the devout among Hindus of the Vaishnavite order.

The great and general religious festival of the Laiharaoba, or the rejoicing of the Gods {Lai ss Deity, and haradba = to be merry or to make merry), is thus described by Colonel McCuUoch,* "Particular families have particular gods, and these at stated periods they worship, or literally ' make happy.' This worship consists in a number of married women and un- married girls, led by priestesses, accompanied by a party of men and boys all in dresses of a former time, dancing and singing, and performing various evolutions in the holy presence. The women carry in their hands fruits, etc., part of which is pre- sented to the deity, and part scrambled for by the girls. In some instances the god is represented by an image, but often there is no such representation, and a place is merely prepared in which he is supposed to be during the worship. The presence of the god, however, in either way, impresses the worshippers with no awe; on the contrary, it appears to be a cause of fiin and jollity."

The next great festival to which attention is now to be drawn, is the Chirouba, a name which my informant, a Hindu of high caste from Bengal, stated to be connected with charak puja, a derivation with which it is impossible to agree. The festival is closely connected with the choice of a chdhitaba or name-giver for the coming year, and takes place at the end of the Manipuri month, Lamda, which corresponds with the middle of April, The Deity in whose particular honour the festival is held, is Senamehi, the administrator, as my friend and informant says, of the Universe. It is regarded as an auspicious day, and on it no work is done except that they clean their houses out very carefully. They wear new clothes and break all their old chaphtis or earthenware cooking pots and eat alone without any guests. It is a day of powerful influence on the coming year, and on it takes place the selection of the choMtdbba^ the man who gives his name to the year, who bears all the sins of the people for the year, and whose luck, good or ill; influences the luck of the whole country. The derivation of the word chahitaba is obscure. Kum, the word for a year in so many Tibeto-Burman dialects, is not unknown in Meithei, but chain is peculiar to it. Some say that it is connected with the word diahi or chai = a stick, and tdba, means to count, to count by flticks, the practice of the Manipuris being to calculate by means of a heap of sticks.* Others derive it from chahi = a year, and taba = to fall, because the fall of one year implies the com- mencement of a new year* According to another opinion, didhi bears the meaning of a year and taba is connected with the root takpa = to show or indicate, to point out — thus making the phrase to mean the person who indicates or names the yeax-

All reckonigs of time are made by chahitabas as well as by the Hindu system, and there are still men in the State who can repeat all the chdkitabas from the institution of the custom by Kiamba, in about 1485, who appointed Hiang Loi Namoi Chaoba to be the first chahitaba.

The maibas nominate the man and compare his horoscope with those of the Raja and the State generally, and if they satisfactorily correspond, as is natural they should, the candi- date together with the outgoing chdhitdha appears before the Eaja and the assembled multitudes when, after worshipping his spiritual director, the Guru and Ms own God (probably his tribal deity), the retiring cIidhitdM then addresses the in- coming officer in the following terms : " My friend, I bore and took away all evil spirife and sins from the Raja and his people during the last year. Do thou likewise from to-morrow until the next Chirouba," Then the incoming chaJiitdba thus addresses the Raja: *'0 son of heaven, Ruler of the Kings, great and ancient Lord, Incarnation of God, the great Lord Pakhangba, Master of the bright Sun, Lord of the Plain and Despot of the Hills, whose kingdom is from the hills on the east to the mountains on the west, the old year perishes, the new cometh. New is the sun of the new year, and bright as the new sun shalt thou be, and mild withal as the moon. may thy beauty and thy strength grow with the growth of the new year. From to-day will I bear on my head all thy sins, diseases, misfortunes, shame, mischief, all that is aimed in battle against thee, all that threatens thee, all that is bad and hurtful for thee and

- omens are also taken by means of sticks thrown loosely on the

Ground. thy kingdom." The Raja then gives the new chahitaba a number of gifts, including a basket of salt.* The chahitaba is exempt from Iallup, and receives many rivileges from the State. The chahitaba offers brass plates accompanied by sacred offerings of fruit and flowers to the Baja, to the maiba and attendants of the Deity Pakhangba, to the maiba Unsang or College of the Maibas, (exorcists' office as the term is translated by my Hindu friend) to the College of the Astrologers, to the Maharani, to the Overseer of the Boyal stores, and last, not least, to the Hindu Deity Govindji, the Family God of the Royal family.

It is interesting to note that certain classes of persons are ineligible for this important office, such as Bajkumars, possibly because they are neyer out of the line of succession and there- fore undesirable, Panggans or Manipuri Musalmans, Nagas who find consolation in an ampler dietary, and Thangjams and Konsams, blacksmiths and brassworkers. I can give no reason for the ineligibility of the two last classes, except that it is possible that they occupy or once occupied so low a position in society that they were excluded.

The appointment of a chahitaba rests on the desire to find a scapegoat to bear the sins of the community or of the individual Raja, the idea which is clerly. the motive of the scapegoat ceremony which takes place at the foot of the holy hill Khabru on the grassy plain, to which the significant name Kaithen- manbi, the meeting place of the ghosts, has been given (Kaithen = market or gathering place, mdnM, from manba = to resemble, to appear). Thither annually the Raja went in solemn procession to sacrifice a white goat, male without blemish, to the God Khabru whose abode it was, and to leave there fish and an offering of new cloths. But there come times when such ordinary devices as these fail of their purpose, and

'Chi=rouba may thus mean salt-taking. Chi is the word for salt in many of the cognate Tibeto-Burman dialects, and rouba = laoba, to take. There are many words which are obsolete or unused in Manipuri, or only used in a special sense, or in combinations, which are in common use in the other Tibeto-Burman dialects. The best examples are : tui water, which in Meithei is found in titren, but is used by Nagas and Kokis ; lengha = to go, to move, which, in common use in that sense in Kuki, is only used of the Raja in Meithei. it is necessary to have recourse to special sin-takers. Generally some criminal is found to take upon himself the guilt of the Raja and Rani who, clad in fine robes, ascend a staging erected in the bazar beneath which crouches the sin-taker * The Raja and Rani then bathe in the screened tent on the stage, and the water they use in their ablutions, drops over the man below, to whom they give their robes and sins. Clad in new raiment, the Raja and his consort mix among their people until evening of that day, when they retire into a seclusion which may last for a week, and during which they are said to be namungba, sacred or tabu.

Sometimes the transference of sins has been satisfactorily accomplished by the simple device of presenting the Royal cloth to a " Sin-taker."

More than one ethnologist of note has pointed out that among communities which are animistic and which subsist by agriculture, rain-worship assumes peculiar importance, and to this statement the state of things in Manipur is no exception. There are Hindu ceremonies, performed by Brahmins, such as the milking of 108 milch cows before the temple of Govindji, or the presence of the images of Radha Krishna at the river bank, when the people cry aloud for rain and the priests mutter mantras. But the great characteristic of the rites of the pre- Hindu system is the management of these rites by the maiba, the piba, or in more important cases by the Raja, who is, in fact, regarded not only as a living Deity, but as the head of the old State religion and the secular head of the whole people, including the Ningthaja or Royal clan. The hill which rises to the east of Imphal, and which is called Nongmaiching,t is the scene of a rain-compelling ceremony. On the upper slopes there is a stone which bears a fanciful resemblance to an umbrella, and the Raja used to climb thither in state to take water from a deep spring below and pour it over this stone, obviously a case of imitative magic. It was said that to erect an iron umbrella on the hill was an almost sure method of getting rain, when occasion needed. And there are many other

- Cf. The old Ahom custom, which was similar. It was called the

Rikkhran. rites and ceremonies all of which are destined to provide the thirsty land with the rain, without which all are about to die, and at all of which the Raja should be present. Some- times his great racing-boat was dragged through the mud and slime of the empty moat with the Baja and his semi-sacred father-in-law, the Ang6m Ningthou, seated together in the stem.

The Kangla, the place where the most mysterious rites per- taining to the coronation of the Raja were performed, was the scene of a ceremony of which I have never been able to get a proper or intelligible account. Suffice to say that whatever happened there, it was sufficient to give rise to the story that human sacrifices had been made in the dire extremity of the country, for in older times, as I was told, the blood of some captive would have brought the rain. The sacrifice of ponies for this purpose may be due to the operation of what has been called the law of substitution. But the activity of the people does not confine itself to merely witnessing these official ex- hibitions. The men, headed on the worst occasions of prolonged drought by the Raja, strip themselves of all their clothes and stand in the broad ways of Imphal cursing one another to the fullest extent of an expressive language.

The women at night gather in a field outside the town, strip themselves and throw their dhdn pounders into a neighbouring pool in the river and make their way home by byways. Of course there is the legend of a Peeping Tom, for whose outrage on the royal decency the country went rainless for a whole year. To some maiba the wicked act was revealed in a dream, and then justice was done and the country saved.

The Kumul Ningthou worships the Tribal Deity Okparen on behalf of the clan whenever rain is needed. He has to abstain from meat of any kind and from all sexual intercourse before this puja. To purify him water,is poured over his head by a virgin from a new jar which is promptly broken. He does not worship Sena Mehi or Laimaren.

Dr. Brown * states that " in the event of Munniporie Hindoo losing his caste from any reasons, . . . the individual has to take up liis abode in a Naga village, eating with the inhabitants. ... Its object seems to be to start the ofifender afresh from the lowest class." This is denied by many "but has all the natural appearance of a purificatory rite. Does this throw any real light on the " affinities " of the Meitheis ? *

Sacrifices

Each clan has its tribal Deity, and certain flowers, fruits, etc., are set aside for each Deity. Thus the Ningthaja clan oflfer the lotus, the lime, the mahasir fish, the mongba — a small rat, I believe. Their special day is Monday (Ningthoukaba), and their special month is Inga.

Priesthood

Side by side with the Brahmin, there exist the priests and priestesses of the animistic faith who are called maibas and maibis, a word which also connotes, nowadays, the practice of the healing art because, as the language of the people clearly tells, a man is said to be ill (a-na-ha) when he is possessed by a nat^ The heads of the clans are priests, and assume charge of the ritual of the tribal worship, while the Raja, the head of the Ningthaja clan and the head of the whole confederacy, is the high priest of the country.

The Chronicles of the State contain frequent and early mention of the maibas, while we have it on the authority of Colonel Mcculloch that the maibis " owe their institution to a princess who flourished hundreds of years ago, but whether they have preserved all their original characteristics I cannot certainly affirm. At present any woman who pretends to have had a ' call ' from the deity or demon, may become a priestess. That she has had such call is evidenced by incoherent language and tremblings, as if possessed by the demon. After passing her novitiate she becomes one of the body and practises with the rest on the credulity of the people. They put some rice or

In Tibetan, nat or nsd is to be ill." The root nat is lengthened in Meithei by the suppression of the final consonant. some of the coin of the country into a basket, and turning it about with incantations, they pretend to divine from it. They dress in white/'* Elsewhere he remarks that the priestess looks after Pakhangba the snake.f

The maiba is for the most part a medical practitioner with a good deal of empiric knowledge, which he supplements with brazen ingenuity, but he is also the rain doctor to whom men turn for help after the failure of all other methods. He is employed in all cases where purely magical ceremonies are performed, a sure sign of his true position.

The pibas or heads of the clans are now dignified officers holding in the case of the pibas of the Angom, Eumul and Luang clans, the title of Ningthou or king. They officiate at the annual ceremonies, which seem to be in honour of the eponymous tribal ancestor, or which are connected with the crops, and special precautions have to be taken against any impurity on their part. But pre-eminent above them all is the Meithei Ningthou, who is not only the head or piha of the Ningthaja clan, but the chief of his people as well. His appearances in a priestly capacity are infrequent, and limited to some great calamity, such as prolonged drought, when he will intercede with the powers that be, on behalf of his people. It is needless to say that the sacred person of the Saja is protected by many tabus. Some pertain to his royal office, while others are as distinctly intended to guard his priestly sanctity from pollution. He may in times of special distress avert the wrath of heaven by transferring his sins and those of the principal Rani to some wretched criminal, who thereby obtains a partial remission of his sentence and as a reward receives the discarded robes of the royal pair. In this connection it may be mentioned that the chahitdba, the man who gives his name to the year, and who for the space of one year takes upon himself the sins of the whole people, enjoys for the term of his office a sanctity which is indistinguishable from that of the priest. Full details of the method and rites of appointing the chahitaba are given above.

Nature Worship

Ira, the Sky God, has his counterpart in the Meithei m, where the Deity Sorarel possesses all the attributes ally assigned to Indra, with whom he is now identified e ingenious Hindus. The lofty hills which surround the |r are named after the Deities whose abode they are held Khabru, on the north-west, looks down on the plain of lenmanbi, the meeting-place of the spirits, and thither ally, in olden times, the Raja used to go in state to tiate the Deity. When the thunder bursts on the summit e mountain, men say the God fires his cannon ; when they 1 winter the snow fall on the topmost peak, the God is ding his cloth. There are Thangjing, Marjing, Laiching, the sacred hill, Nongmaiching, which seems to be derived Nong = sun or rain, niai = face or in front of, and ching = and to mean the hill that fronts the rain or sun. Does deity give the name to the hill, not the hill the name to deity ?

om the ballad of Numit kappa we know that they believed once upon a time there were two Sun Gods riding on white is, and now the moon is the faint pale image of the one was wounded. Beneath the earth lives the earthquake ^ who shakes the earth, and to whom they pray nga chaJc, ire us our fish and rice," whenever he shakes the earth, lere are many rain piijas, but there does not seem to be one rain Deity. In some cases the prayers of the wor- pers are addressed to the tribal ancestor, and the puja )rmed entirely by the piba or head of the tribe. If we ) not a thunder Deity, we have at least the legend of a oder Deity enshrined in the language of the people. In thei the word for lightning is nong'thdng-kup-pa, which is ved from nong = rain, thdng = dao, kup = to flash, and has efore the meaning of the flash of the dao of the Eain God. f among the Thados we find the legend of the Eain Deity a hty hunter coming home aweary from the chase and thirsty. )th was he when he found that his wife had no zu ready for , and he brandished his dao at her, roaring hoarse threats of punishment for her neglect of her wifely duties, and then in his haste to quench his mighty thirst, he spilt the drink. It is curious to observe the lacuna ; the Thados have the tale but not the word, while the Meitheis have the word but not the tale.

Ceremonies Attending Birth

The Meitheis follow the ordinary rules of modem Vaish- navites in the matter of birth ceremonies, but have, in addition, a small puja in honour of the Imung Lai or the Household God, which is performed by the head of the household. This latter ceremony is, of course, non-Hindu.

Naming

Both Colonel Mcculloch and Dr. Brown give explanations of the system of naming employed by the Meitheis, and concur in regarding the names as in many cases derived either from &e profession or some personal peculiarity of the founder of the family. Colonel McCulloch f says that " Individuals are spoken of and known by their surnames ; the laiming, or if I may use the expression, the Christian name, being seldom known to or used by any but the nearest relatives. All but the Boyal family have surnames. The Christian name is written last. The.intro- duction of surnames took place in the reign of Chalamba. about two hundred years ago, and of the laiminff since the profession of Hindooism. The surnames are evidently derived from some peculiarity in the individuals who first bore them. The oldest family of Brahmins in the country is called Hungoibum. Eungoi means a frog, and that such a name should be given to a person who bathed so much more frequently than Munniporees had been accustomed to see, seems very natural. The same is the case with almost every family ; all the surnames indicatiog either the profession or some peculiarity of its original holder."

Dr. Brown treats the matter in a different manner, and says

- Wan aghin is the Thado for thunder, and means the noise of the sky

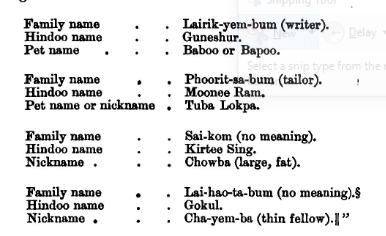

from wan = sky and ghin = noise ; while me aying is their expression for lightning, from me = fire and aying = darkness. that *' The names of the Munnipories are given on rather a com- plicated system, which may now be explained. In the first place, all the inhabitants have what is called a yoom-nak,* or family name, corresponding with our surnames ; some of these names are evidently derived from the ancestor's employment, as Lairik- yeni-bum, corresponding with our English name, ' Clerk or Scrivener 't; Phoorit'Sd'hum, tailor Thangjaba, smith, etc., etc. Next is the Hindoo name given by the astrologers, accord- ing to Hindoo custom, and, lastly, a nickname, or pet name, given to them when children, and by which they are known all their lives frequently. Sometimes the family name is alone used, occasionally the Hindoo, and very often the nickname ; it is thus no easy matter some times to identify a Munniporie by name. I give a few examples of complete names, with their meanings when known.

It thus appears that there is a name which is not permitted to be common property, that there is generally a nickname, or pet name, which is known to and used by the world at large, and that the family, or yumndk name, is derived from either the occupation or some peculiarity of the original founder of the

- yum = house, and nak is connected with the word nai = to belong

to, nuk also means near.

Thang = dao, chdn = to manufacture, lairik = book, yem, from ymig = to look at. The man who looks at books.

Phurit = coat, and sa = to make. Probably means giver of the flower known as the Lai-hao.

family — that is to say, the yumnak name is in origin descriptive in much the same way as the nickname or supplementary name now is.

Furthermore, it should be mentioned that it is customary for the Raja to assume a formal name on or after his accession by which he is described in all official documents. Thus, the Maharaja Chandra Kirti Singh was also known as Nowchingleng Nongdren Khomba after the year 1870, though he actually suc- ceeded to the throne many years before that date. Thus the Raja, to whose reforming zeal the country owes the introduction of Hinduism, is variously known as Gharib Nawaz, Pamheiba, or Moianba. Doubtless the explanation of some, at least, of the Royal names is that they commemorate some incident or exploit which occurred during the reign, such as that of Khagenba, whose name may possibly mean " Conqueror of the Chinese " (from Khagi = Chinese, and yanba = to slaughter, or defeat).

Toga Virilis

The assumption of the sacred thread by a Meithei is regarded as proper when a lad has reached man's estate, but it is often delayed, and may be postponed without serious inconvenience. There is a curious custom which requires the eldest son of the Raja, when twelve years of age,- to go into the jungles alone as a sign that he possesses the necessary strength and courage,, and cut twelve bundles of fire- wood with a silver-hilted dao, which, tradition says, was presented to Khagenba by the TTing of Pong, that mysterious kingdom whose exact geographical posi- tion has vexed the minds of so many inquirers,* who either foigot, or were never acquainted with, the peculiar laxity of the Meitheis in regard to the geography of unknown countries. The people of Pong were the Shans beyond their ken who visited them, and it is quite legitimate to conclude that the kingdom of Pong meant the powers who at the time were in supreme authority in the Shan States with which the Meitheis had dealings.

- Gazetteer of Upper Burma

Marriage

The following excellent note by Mr. H. A. Colquhoun, I.C.S., gives all that can be desired in the way of an account of the marriage rites in vogue among the Meitheis : — ** The usual marriage ceremony is that known as Prajapati or Brahma. After the parents have settled the preliminaries, the announce- ment of the forthcoming marriage or Yathang tJCaha takes place. This is followed by offerings of sweetmeats or hdjapot on three separate occasions from the bridegroom to the bride's family. The actual ceremony is held at the bride's house ; a large party assembles, and a Kirtan is held, the bride sitting in front of the bridegroom. Mantras are recited, and the ancestry of the pairs up to the great-grand-parents is repeated. The sapta pradakhsin follows: the bride walking ceremonially seven times around the groom and casting flowers upon him ; garlands (leipareng) are placed on both, and the company pros- trate themselves before them. They are then seated side by side, and their innaphi, or ehadars, are fastened together. The Hari Kirtan, and the prostration are again repeated. The bride then enters the cooking-room followed by the groom. The pair sit on the same mat, and place pan (panna Kutap), and subsequently sweetmeats (kangsuU) in each other's mouths. Offerings of pan are made to them by friends and relatives. The party then marches to the bridegroom's house, the bride being carried in a litter at the head of the party. A large and substantial wooden bed is a prominent feature of the procession.* On the sixth day following there is a feast at the house of the bride's family, and the ceremony is then complete.

"Other forms of marriage are also practised, the Sampati Eajbibaha, Eakshasa and Gandharva, the latter being, of course, constituted by simple cohabitation."

Colonel McCulloch states that "Although to become man and wife it is not necessary that the marriage ceremony should be performed, still it is usually performed, but as often after as before cohabitation." t It should be noted that the penalty on irregular marriages is the loss of the right to obtain offices about

- Cf, Robertson Smith, Marriage and Khiship

the Royal person and the inquiries which were necessitated by the census of 1901, caused some genuine alarm from the rumours sedulously spread that, as in the days of that stem old despot Chandra Kirti Singh, severe punishments awaited those who had taken advantage of the laxity of the British adminis- tration in these matters to contract connubial alliances without the usual sanction of the Brahmin. The fact is that most Manipuris regard cohabitation and public acknowledgment as sufficient, provided that due regard has been paid to the rules restricting marriage to members of the Meithei tribes and forbidding the intermarriage of persons of the same clan, scUei,

Among the Lois gifts are exchanged and a feast prepared which culminates in the sacrifice to the Imung Lai, to the Lam Lai, and to the Umang Lai.

At Sengmai, where the manufacture of ardent spirits is the chief industry, presents of zu were offered to the girl's parents when the marriage was under discussion. If these gifts were peremptorily refused nothing further happened, but if the first invitation was accepted, the matter came into the range of practical politics and omens were taken to ascertain whether or not the marriage was favourably regarded by divine authority. Eventually the day was fixed, and the bride-price handed over, and the feast made ready.

Death, And Disposal Of The Dead

All the rites and ceremonies consequent on the death of a Mei- thei are in the hands of the Brahmins, and there is therefore no feature to which attention should be specially drawn. Sepulture is only allowed in the case of children dying under the age of two years, and the burial takes place by preference on the bank of some river. I agree with Mr. Colquhoun in regarding the use of a box-like structure on the funeral pyres as a trace of the former method of sepulture for adults. It is well known that up to the advent of Hinduism, the dead were buried, and the Chronicles mention the enactment by Khagenba of a rule that the dead were to be buried outside the enclosures of the houses. Gharib Nawaz ordered the Manipuris to exhume the bodies of their ancestors, which they formerly used to bury inside their com- pounds. At a later date in his reign, in the year 1724, Gharib Nawaz exhumed the bones of his ancestors and cremated them on the banks of the Engthe Eiver, and from that time ordered his subjects to bum their dead. The system of cremation in vogue among the Meitheis is very thorough, as Mr. Colquhoun remarks, and the frontal bone is preserved and thrown in the Ganges at a later date, as opportunity arises.

The corpse is never carried over the threshold of the main door, sometimes a hole is cut in a wall or the tiny side entrance used.*

Festivities, Domestic And Tribal

Mention has been made of the various Hindu festivals such as the Dussera, and of the festival which is tribal in reality, known as the Laiharaoha. It is doubtful whether the waritabas or parties given by wealthy folk, at which iseisakpas, or wander- ing minstrels, recite the stories of the wanderings of Ching- thangkhomba, or of the unhappy loves of Khamba and Thoibi, or the adventures of Numit kappa, are of a religious nature ; but so closely are the threads of religion interwoven in the web of life of the people, that strange as it may seem to those who are accustomed to a religious system which provides for one day of the week only, it is probably just to mention these gatherings in this place. Recited in a dialect which is un- intelligible to the listeners, despite the nasality of the tone in which they are recited, and despite the jangling accompaniment of the pena, these balleids possess something of real beauty. The audience knows not the exact import of the words they hear, but it knows the sad, the mirthful passages as they occur, and greets them with tears or with appropriate laughter. Meitheis or Moirangs, they listen with avidity to the trials of Khamba and Thoibi, the ballad which cannot fail to remind one of the stories of the Trials of Hercules, and which is held true by all, for to this day are not the clothes worn by these worthies still preserved in the temple at Moirang ?

- See Jevona, Introduction to Plutarch's Romane Questions

Genna

The detrition of the ancient customs which, begun by the introduction of Hinduism, has moved on with increasing rapidity since the country became the prey of the Burmese forces under Aloung Pra and his successors, prevents us from estimating the real extent to which the genua customs used to prevail among the Manipuris. If to-day they have not the thing itself, they have at least the memory of it in the word namungba, which covers precisely the same range of ideas as the word genim. There are even survivals of practices which among Nagas we call genna, and these I will now proceed to discuss.

It will be seen that among Naga tribes the head of the clan is divided from the common herd by gennas of food and speech. Thus it is namungha for any Manipuri to address the Eaja except in a peculiar vocabulary.* We may compare this with the prohibition against the use of certain profane words by priests and kings. Again they say that food cooked in a pot which has been used before, as ndmungba to the Eaja. Indeed, of every prohibition which rests on vague indefinable sanctions, they use the term ndmungba.

Each clan in Manipur regards some object as ndmungba to it, and believes that if by inadvertence some member of the clan touches one of these objects he will die a mysterious death, or suffer from some incurable, incomprehensible disease, pine away and die. The object which is tabu to the Ningthaja clan is a reed, that to the Moirangs the buffalo, in the case of the Kumuls it is a fish. Again, if a man falls from a tree, the elders of his clan may gather round that tree and solemnly declare it, even all others of its kind, to be ndmungba to their tribesmen. Yet another instance of the working of ideas which in other parts of the world have elaborated the system of tabu, the trees which crown, the tumulus in Imphal, beneath which, according to common, tradition, repose the bones of the Moirangs who fell in the last great battle with the Meitheis, are ndmungba to the men o£ Moirang to this day, and between them no Moirang may go, fox>

♦ See J. G. Frazer : Golden Bovgh if one were so bold as to venture through, ruin would overwhelm his fellow clansmen.

It is remarkable that to this day the Moirangs whom I have described as still clinging to then* independence and separate- ness, preserve something like a system of gemm, participated in by the whole clan, and, like the Naga gennas, held periodically and connected with the times and seasons of cultivation.

Beyond these few cases it is now impossible to describe the genna system as it once existed ; btit I hope I have said enough to show that to this present day the fundamental ideas which underlie all genna rituals, are alive and active in Manipur.

To the curious in such matters the relationship of the three roots, mang = dream, mung [namungha = na = la = lai = Deity + mung] and mang = to be polluted or to be destroyed, may be commended for further investigation. We know that the legnds of the country declare that the Gods appeared in dreams * and gave orders as to all sorts of affairs, thus legis- lating through the mouth of the dreamers. Mdng-ha (to be polluted) has a religious significance, for it applies to cases of ceremonial pollution. If we admitted, and it is temptingly easy to do so, that ndmungba is derived from La = God and mung (? = mang or ? = mdng), we should have an interesting instance of philology assisting our theory gratuitously. We have high authority for connecting the Meithei word ising with the Tibetan chhu, so that perhaps these humble guesses at philo- logical truth are not of the order which neglects the consonants and is rude to the vowels. In fact, the connection between divine appearances in dreams, sacred prohibitions, tabu and pollution, is of the closest.

- Cf, Note on Moirain Chronicle.

See also

The Meitei Language and Grammar

The Meitei: Religion

The Meitei: Traditional economy