Kolaba District, 1908

(Created page with "=Kolaba District, 1908= District in the Southern Division of the Bombay Presidency, lying between 17 degree 51' and 19 degree 8' N. and 72 degree 51' and 73 degree 45' E., ...") |

(→Physical aspects) |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

of the Bor pass stretches north-west in the flat tops of Matheran and | of the Bor pass stretches north-west in the flat tops of Matheran and | ||

Prabal. Running north and south through the centre of the Panvel | Prabal. Running north and south through the centre of the Panvel | ||

| − | + | is the broken spur which ends southwards in Karnala or Funnel | |

hill. Farther west is the lower line of the Parshik hills, and in the | hill. Farther west is the lower line of the Parshik hills, and in the | ||

south the long ridges that centre in the precipitous fortified peak of | south the long ridges that centre in the precipitous fortified peak of | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

inland subdivisions is much heavier than on the coast, amounting to | inland subdivisions is much heavier than on the coast, amounting to | ||

130 inches. The annual fall at the District head-quarters averages | 130 inches. The annual fall at the District head-quarters averages | ||

| − | 88 inches. | + | 88 inches. |

| + | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Latest revision as of 09:20, 6 March 2015

Contents |

[edit] Kolaba District, 1908

District in the Southern Division of the Bombay Presidency, lying between 17 degree 51' and 19 degree 8' N. and 72 degree 51' and 73 degree 45' E., with an area of 2,131 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Bombay harbour and the Kalyan and Murbad talukas of Thana District ; on the east by the Western Ghats, the Bhor State, and the Districts of Poona and Satara ; on the south and south-west by Ratnagiri ; and on the west by the Janjlra State and the Arabian Sea.

[edit] Physical aspects

Kolaba District is a rugged belt of country from 15 to 30 miles broad, stretching south from Thana and Bombay harbour to the foot of the Mahabaleshwar hills, 75 miles south-east. Situated between the Western Ghats and the sea, asnects the District contains spurs of considerable regularity and height, running westwards at right angles to the main range, as well as isolated peaks or lofty detached ridges. A series of minor ranges also run north and south between the main range and the sea. The great wall of the Western Ghats forms the chief natural feature. Of other ranges, the chief is the line of hills that from near the foot of the Bor pass stretches north-west in the flat tops of Matheran and Prabal. Running north and south through the centre of the Panvel is the broken spur which ends southwards in Karnala or Funnel hill. Farther west is the lower line of the Parshik hills, and in the south the long ridges that centre in the precipitous fortified peak of Manikgarh (1,800 feet). South of Bombay harbour a well-marked rugged belt rising in bare rocky slopes runs south and south-east, with the two leading peaks of Kankeshwar (1,000 feet) in the extreme north and Sagargarh (1,164 f eet ) about 6 miles farther south. The most famous peak in the District is Raigarh, on a spur of the Western Ghats, where Sivajl built his capital.

The sea frontage of the District throughout the greater part of its length is fringed by a belt of coco-nut and areca-nut palms. Behind this belt is situated a stretch of flat country devoted to rice cultivation. In many places, along the banks of the salt-water creeks, there are extensive tracts of salt marsh-land, some of them reclaimed, some still subject to tidal inundation, and others set apart for the manufacture of salt. A few small rivers, rising in the hills to the east of the District, pass through it to the sea. The chief of these are the Ulhas, Patalganga, Amba, Kundalika, Mandad, and Savitrl. Tidal inlets, of which the principal are the Ulva or Panvel, the Patalganga or Apta, the Amba or Nagothana, the Kundalika, Roha or Chaul, the Mandad, and the Savitri or Bankot creek in the south, run inland for 25 or 30 miles, forming highways for a brisk trade in rice, salt, firewood, and dried fish. These inlets have of late years silted up to a considerable extent, and it seems possible that their value as highways may in future decline on this account. The creek of the Pen river is navigable to Antora, 2 miles from Pen, by boats of 7 tons during ordinary tides, and by boats of 35 tons during spring-tides. Near the coast especially, the District is well supplied with reservoirs. Some of these are hand- somely built of cut stone, but of no great size, and only a few hold water throughout the year.

The rock formation is trap. In the plains it is found in tabular masses a few feet below the soil and sometimes standing out from the surface. In the hills it is tabular and is also found in irregular masses and shapeless boulders, varying from a few inches to several feet in diameter. In many places the surface of the trap has a rusty hue showing the presence of iron. Kolaba has three hot springs, at Unheri near Nagothana and at Son and Kondivti in Mahad.

The forest areas of Kolaba contain a variety of trees, of which the commonest are teak, mango, ain (Terminalia tomentosa), jdmba (Xylia do7abrifomnis), and kinjal ( Terminalia paniculatd). The leaves of the apta (Bauhinia racemosa), which is too small to yield timber, are used in the manufacture of native cigarettes ; cart-wheels are made from the timber of the khair {Acacia Catechu) ; and the fruit of the tamarind (chinch) is largely utilized as medicine and spice. The gorak chinch or baobab (Adansonia digitata), though growing to an enormous size, is not utilized. Fuel is provided chiefly by the mangrove and tivar (Sonneratia acida), which grow in the salt marshes, and by such creepers and shrubs as the phalsi (Greivia asiaiica), kusar (Jasminum latifolium), kaneri (Nerium odorum), and garudvel (Entada scandens). Other creepers are the rantur (Atylosia lawii), matisul (leonotis nepefifolia), and sdpsan {Aristolochia indica), which are used medici- nally, and the shikakai (Acacia concinna), which bears a nut of cleansing properties.

For a hilly and wooded District, Kolaba is poorly stocked with game. Tigers and leopards are occasionally found, especially in the Sagargarh range, and bears on the Western Ghats. Hyenas and jackals abound. Bison, sdmbar, and chital have been shot, but are very rare. Of game-birds, the chief is the snipe. Duck are neither common nor of many kinds. The other game-birds are partridge, quail, plover, lapwing, curlew, peafowl, grey jungle-fowl, red spur-fowl, and the common rock and green pigeons. Snakes are numerous but of no great variety, and the cobra, though common, does not cause any large number of deaths. In the coast villages, the fishermen cure large quantities of fish for export to Bombay by the inland creeks. The sea fisheries, especially of the Allbng villages, are of considerable impor- tance, affording a livelihood to 6,800 fishermen in the District ; but the latter are gradually spoiling their own prospects by the use of nets so constructed that small fry, as well as half-grown fish, are exterminated before they attain a marketable size. The chief species caught, mostly by means of stake-nets, are pomphlet, bamelo or bombil, and hahva.

There are four distinct climatic periods — the rains from June to October ; the damp hot season in October and November on the cessation of the rains ; the cold season from December to March ; and the dry hot season from March to June. In the region about Allbag there is always a sea-breeze. Mahad is almost entirely cut off from the sea-breeze, and is subject to much greater changes of temperature than most of the District. In the hot months the heat is very oppressive in Karjat, except on the hill-tops. The temperature varies from 65 in January to 92 in May, with an average of 8o°. The rainy season is considered the healthy period of the year. The rainfall in the inland subdivisions is much heavier than on the coast, amounting to 130 inches. The annual fall at the District head-quarters averages 88 inches.

[edit] History

Hindu, Muhammadan, Maratha, and British rulers have, as through- out most of the Peninsula, in turn administered the District of Kolaba. But it is the rise, daring, and extinction of the pirate power of the Maratha Angna that vests the history of this part of the Konkan with a peculiar interest. The early rulers were most probably local chiefs. Shortly after the beginning of the Christian era, the Andhra dynasty, whose capital was Kolhapur, were the overlords of Kolaba. About this time (a. d. 135 to 150), the Greek geographer Ptolemy describes the region of Kolaba under the name of Symulla or Timulla, probably the Chaul of later days. In Ptolemy's time the Satavahanas or Andhras were ruling in the Kon- kan as well as in the Deccan ; and for many years the ports on the Kolaba seaboard were the emporia of a large traffic, not only inland, over the Western Ghats across the Peninsula, but by way of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf to Egypt, Arabia, and Abyssinia. In the sixth century Kolaba, with all the Northern Konkan, came under the sway of the Chalukyas, whose general, Chana-danda, sweeping the Mauryas or local rulers before him ' like a great wave,' captured the Maurya citadel Purl, ' the goddess of the fortunes of the western ocean.' In the thirteenth century, by which time the rule of the Chalukyas had passed away, the District was held by the Deogiri Yadavas.

Immediately prior to the appearance of the Muhammadans, tradition assigns to Kolaba a dynasty of Kanarese kings, probably the rulers of Vijayanagar. Nothing, however, is known about them. The Bahmanis, who ruled from 1347 to 1489, reduced the whole Konkan to obedience, and held Chaul as well as other posts in Kolaba District. The Bahmani dynasty was followed by kings from Gujarat. A period of Portuguese ascendancy established at Chaul (i 507-1 660) preceded the rise of the Angrias, and was partly contemporaneous with the conquest of all the rest of the District by the Mughals and Marathas. The Mughals, who acquired the sovereignty in 1600, were in 1632 ousted by Shahjl Bhonsla, a servant of the Bijapur kings and father of Sivajl, who founded the Maratha power. Sivajl built two small forts near Ghosale and Raigarh ; repaired the strongholds of Suvarndrug and Vijayadrug, which stand on the coast-line below Bombay; and in 1674 caused himself to be enthroned at Raigarh. Nine years after SivajT's death in 1680, the seizure of Raigarh restored control of the country to the Mughals. The period of the Angrias, who terrorized the coast while the Muhammadans were powerful inland, lasted for 150 years — from 1690 to 1840, when Kanhoji II died in infancy and the country was taken over by the British. Kanhoji, the first of the Angrias, was in 1698 the admiral of the Maratha fleet, having his head-quarters at Kolaba, an island-fort close to AlTbag and within 20 miles of the present city of Bombay. From here he had long harassed shipping on the coast from Malabar to Bombay; in 17 13 he threw off his allegiance on Raja. Shahu, and having defeated and captured the Peshwa, set up an independent rule in ten forts and sixteen minor posts along the Konkan coasts. Having conquered the Sldls of Janjlra, his rivals in buccaneering, Kanhoji, with a considerable fleet of vessels, ranging from 150 to 200 tons burden, swept the seas from his fort of Vijayadrug. In 17 17 his first piracies against English trade occurred. In retaliation the English assaulted Vijayadrug, but the assault was beaten off. On two occasions within the next four years, Kanhoji withstood the combined attacks of the English and Portuguese. On his death in 1731 the Angria chief- ship was weakened by division between Kanhojf s two sons, of whom Sambhojl Angria was the more enterprising and able. Sambhojl was succeeded in 1748 by Tulajl ; and from that date until the fall of Vijayadrug before the allied forces of the Peshwa and the British at Bombay, both British and Dutch commerce suffered severely from the Angria pirates.

In 1756 the fort of Vijayadrug was captured by Admiral Watson and Colonel (afterwards Lord) Clive, who commanded the land forces. Fifteen hundred prisoners were taken, eight English and three Dutch captains were rescued from the underground dungeons in the neigh- bourhood of the fortress, and treasure to the value of \2\ lakhs was divided among the captors. Vijayadrug was handed over to the Peshwa, under whom Manaji and RaghujI, the descendants of an illegitimate branch of the first Angrias, held Kolaba fort as feudatories of Poona. On the downfall of the Peshwa's rule in 1818, the allegiance of the Angrias was transferred to the British. In 1840 the death of Kanhoji II, the last representative of the original Angrias, afforded an opportunity to the Bombay Government to annex the forts of Suvarn- drug, Vijayadrug, and Kolaba. The District has since enjoyed un- broken peace.

Kolaba District., with the exception of the of Allbag, formed part of the dominions of the Peshwa, annexed by the British in 18 18, on the overthrow of Baji Rao. Allbag lapsed in 1840. Kolaba island has still an evil reputation with mariners as the scene of many wrecks. Full nautical details regarding it are given in Taylor's Sailing Directions. Many houses in the town are built from the driftwood of vessels which have gone ashore. Ships are sometimes supposed to be intentionally wrecked here ; the coast near Allbag presents fair facilities for the escape of the crews. The most interesting remains in the District are the Buddhist caves at Pal, Kol, Kuda, Kondane, and Ambivli, and the Brahmanical caves at Elephanta. There are numerous churches and forts built by the Portuguese. The former strongholds of the Marathas and the Angrias are imposing rock-built structures, the chief being Raigarh, where Sivajl was crowned ; Kolaba fort, the stronghold of Angria in the eighteenth century ; Birvadi and Lingana, built by Sivajl to secure his share of Kolaba against his neighbours ; Khanderi, and Underi.

[edit] Population

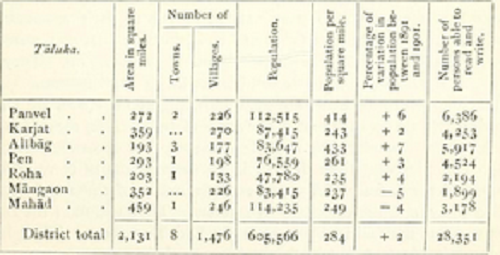

The population of the District was returned at 524,269 in 1872 and 564,892 in 1881. It rose to 594,872 in 1891, and to 605,566 in 1 90 1. The following table shows the dis- tribution of population by tdhikas according to the Census of 1901 : —

The Allbag and Panvel s being naturally well placed and close to Bombay, the density of population is higher than in the rest of the District. The chief towns are Uran, Panvel, Pen, and Alibag. Classified according to religion, Hindus form 94 per cent, and Musal- mans 5 per cent, of the total. The language of the District is Marathi, which is spoken by more than 99 per cent, of the population.

Among Hindus, the most important classes are the Brahmans (24,000), chiefly Konkanasths (14,000), who own large gardens and palm groves along the coast. In the south they are the landlords or khots of many villages, holding the position of middlemen between Government and the actual cultivators. As in Thana, they and Prabhus (6,000) form an influential element in the population. The Vanls (8,000) are traders. Agris (113,000) are tillers of salt land and makers of salt. Marathas and Kunbis (210,000) are rice cultivators. Kolis (25,000) are principally fishermen and sailors. Bhandaris (6,000) are toddy-drawers, and Malls (14,000) are gardeners.

The hill tribes include the Thakurs and Kathkaris ; and the unset- tled tribes, the Vaddars and the Vanjaras. The Thakurs (18,000) are small squat men, with hard irregular features, in some degree redeemed by an honest kindly expression. They speak MarathI, are harmless and hard-working, the women doing as much work as the men. When not employed on land cultivation, they find stray jobs or gather fire- wood for sale. The Kathkaris (30,000) are cultivators, labourers, and firewood sellers, and were originally, as the name implies, cutch (kath) boilers. Their women, tall and slim, singularly dirty and unkempt, are hard workers, and help the men by hawking head-loads of firewood. Kathkaris, as a rule, are much darker and slimmer than the other forest tribes ; they rank among the lowest of the low, their very touch being thought to defile. They eat every sort of flesh, except the cow and the monkey. They are poor, and much given to drinking. In 1902 they were granted large areas of forest for dalhi cultivation, with the object of inducing them to follow more sober habits ; but the object has not been wholly successful, owing to their ignorance of agriculture. The Vaddars (400) are rude, intemperate, and unsettled in their habits, gathering wherever building is going on. They are quarry-men, and make grindstones, handmills, and rolling-pins.

The Bani-Israil, or Indian Jews, numbering about 2,000, are chiefly found in the seaboard tracts. They are of two classes, the white and black ; the white, according to their own story, are descended from the original immigrants, while the black are descendants of converts or of women of the country. A considerable number of them enlist in the native army, and are esteemed as soldiers. They maintain the rite of circumcision, and faithfully accept the Old Testament. Their home language is MarathI, but in the synagogues their scriptures are read in Hebrew. The Jews monopolize the work of oil-pressing to so great an extent that they are generally known as oilmen or telis. The late Dr. Wilson was of opinion that the Bani-Israil are descended from the lost tribes, founding his belief upon the fact that they possessed none of the Jewish names which date from after the Captivity, and none of the Jewish scriptures or writings after that date. Some of the Musalmans are the descendants of converted Hindus ; others trace their origin to foreign invaders ; and a few are said to represent the early Arab traders and settlers. The last named form no distinct community, but consist of a few families that have not intermarried with Musalmans of the country. The percentage of the population supported by agriculture is 72. The industrial class numbers 71,000 in all. Of the 1,202 native Christians in 1901, more than 500 were Roman Catholics and 270 were Congregationalists. The former are found chiefly in the Karanja island of the Uran petha. As early as 1535 there were three churches in the island. The United Free Church Mission of Scotland and an American Mission have establishments in the District. The former maintains a high school, three primary schools for the depressed classes, and two girls' schools.

[edit] Agriculture

There are four descriptions of soil. The alluvial tract is composed of various disintegrated rocks of the overlying trap formation, with a larger or smaller proportion of calcareous sub- . stance. This is by far the richest variety, and occupies the greater portion of the District. The slopes of the hills and plateaux are covered with soil formed by the disintegra- tion of laterite and trap. Though fitted for the cultivation of some crops, such as nagli, van', and san-hemp, this soil, owing to its shallowness, soon becomes exhausted, and has to be left fallow for a few years. Clayey mould, resting upon trap, is called kharapat or ' salt land.' Soil containing marine deposits, a large portion of sand, and other matter in concretion, lies immediately upon the sea-coast, and is favourable for garden crops. Rice is grown on saline as well as on sweet land. Between December and May the plot of ground chosen for a nursery is covered with cow-dung and brushwood ; this is overlaid with thick grass, and earth is spread over the surface ; the whole is then set on fire on the leeward side, generally towards morning, after the heavy dew has collected. In June, after the land has been sprinkled by a few showers, the nursery is sown before being ploughed. The plants shoot up after a few heavy falls of rain. In the beginning of July the seedlings are planted out, and between October and November the reaping commences. On saline land no plough is used, and the soil is not manured. In the beginning of June, when the ground has become thoroughly saturated, the seed is either sown in the mud, or, where the land is low and subject to the overflow of rain-water, the seed is wetted and placed in a heap until it sprouts and is then thrown on to the surface of the water. No transplanting takes place, but the crop is thinned when necessary. Should a field by any accident be flooded by salt water for three years in succession, the crops deteriorate.

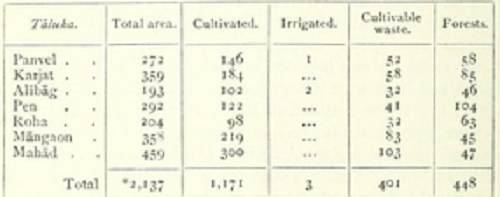

The District is chiefly ryotwari. Khots and izdfatdars own 733 and 17 square miles respectively, while inam lands cover about 7 square miles. The chief statistics of cultivation in 1903-4 are shown below, in square miles : —

- Statistics are not available for 72 square miles of this area. These figures are

based on the latest information. Rice, the chief staple of the District, holds the first place with 391 square miles or 33 per cent, of the total cultivated area. The two main kinds are red and white rice. Red rice is inferior, and is grown only in the salt low-lying lands near creeks. The poorer kinds of grain called nagli (90 square miles), vari (69), harik (27), which form the chief food-supply of the people, are also grown in considerable quan- tities, especially on the flat tops and terraced sides of the hills. Veil occupied 14 square miles and udld 9 square miles. The latter is grown chiefly in Mahad, Mangaon, Karjat, and Roha. Of other pulses, tur and mug are grown in Mahad, Mangaon, and Roha, and gram in Mangaon, Panvel, and Karjat. Sesamum, occupying 6 square miles, is raised mostly in Mangaon and Mahad. Niger-seed occupied 3 square miles. Cotton is now rarely grown, but was cultivated with consider- able success during the great development of the production of Indian cotton at the close of the eighteenth century. San-hemp is grown in Mangaon. The betel-vine and the areca-nut palm are grown in many gardens. The special garden produce is pineapple, which is cultivated in large quantities in Chaul and Revadanda.

The most interesting feature in the agriculture of Kolaba District, especially in Alibag and in Pen, is the large area of salt marsh and mangrove swamps reclaimed for the growth of rice. These tracts, situated along the banks of tidal creeks, are locally known as kharapat or ' saline land.' Most of the shilotris or embankments, which save the land from tidal flooding, are said to have been built between 1755 and 1780 under the Angrias by men of position and capital, who undertook, on the grant of special terms, to make the embankments and to keep them in repair. In several cases the agreements were never fulfilled ; and as the matter escaped notice, the foreshore, which should rightly have lapsed to Government, still remains in possession of the original grantees. For many years these reclamations were divided into rice- fields and salt-pans. The salt-pans were gradually closed between 1858 and 1872 ; and about two-thirds of the area formerly devoted to salt- making has now been brought under tillage. Each reclamation has two banks, an outer and an inner. In the outer bank are sluice-gates which are kept closed from October to June, but, as soon as the rains set in, are opened to allow the rain-water to escape. Two years after the embankment is completed, rice is sown in the reclaimed land, in order that the decayed straw may offer a resting-place and supply nourishment to grass seeds. Five years generally elapse before any crop is raised. More than 14,000 acres have been reclaimed in this way. The reclamation of saline land is encouraged by no revenue being levied for the first ten years, and full revenue only after thirty years. Under the Land Improvement and Agriculturists' Loans Acts advances have been made to cultivators amounting, during the decade ending 1903-4, to 2 lakhs, of which Rs. 61,000 was advanced in 1896-7 and Rs. 33,000 and Rs. 37,000 in 1895-6 and 1 899-1900 respectively.

Except the Gujarat bullocks kept by a few traders and large landowners, almost all the cattle of the District are of local breed. The Kolaba buffaloes are smaller, blacker, and smoother-skinned than those of Gujarat. Sheep are usually imported from the Deccan. Goats are kept by some Musalmans and lower-class Hindus, chiefly for milk. Ponies are brought from the Deccan by Dhangars and Vanjaras. Of the total area of cultivated land, only 3 square miles or 0-5 per cent, were irrigated in 1903-4. The sources are wells and tanks, irrigating respectively 1,300 and 15 acres, and other sources 478 acres. The only part of Kolaba where there is much irrigation is along the west coast of Allbag in a belt known as the Ashtagar or 'eight plantations.' This tract includes the lands of eight villages covering 14 square miles, all of them with large areas of closely planted coco-nut gardens and orchards, irrigated from wells. There are numerous river dams. The wells, whose brackish water is especially suited to the growth of coco-nut palms, are fitted with Persian wheels or rahats.

[edit] Forests

Kolaba is fairly rich in forest, the teak and black-wood tracts being especially valuable. The Kolaba teak has been pronounced by com- petent judges the best grown in the Konkan, and in- ferior only to that of Malabar. Considerable damage has been done to the forests in past years by indiscriminate lopping ; but the villagers are now commencing to realize the need of measures of conservancy. The value of the forests is increased by their proximity to Bombay, for they may be said to He around the mouth of the harbour. The curved knees are particularly adapted for the building of small vessels. The timber trade of the District has two main branches — an inland trade in wood for building purposes, and a coast trade in firewood and crooks for ship-building. The total area of forest in 1903-4 was about 458 ] square miles, of which 449 square miles were reserved,' chiefly in Pen and Nagothana. The revenue in the same year was Rs. 83,750.

Except patches of mangrove along the river banks, the forests of Kolaba are all on the slopes and tops of hills. In the northern s Karjat has valuable Reserves in both the Western Ghats and the Matheran-Tavli range. Panvel also has a considerable forest area, but much of it, except the teak-coppiced slopes of Manikgarh, is of little value. Each of the central s — Pen, Alibag, and Roha — has large rich forests, while the less thickly wooded southern s of Mangaon and Mahad have few Reserves. Teak is the most widely spread and the most valuable tree. Next come the mango, sisu, black-wood ; dhaura [Anogcissus latlfolia), once plentiful but now rather scarce ; and the three principal evergreen hill-forest trees — ain, a valuable and common tree for house-building and tool-making, jamba, and kitijal (Terminalia paniculata). The apta (Bauhinia racemosa), though of almost no use as timber, supplies leaves for country cigarettes or bidis. Nut-yielders include the avla {Phyllanthus Emblica), the tamarind, and the hirda {Terminalia Ckebula) ; and liquor-yielders the mahua, the coco-nut, the palmyra, and the wild thick-stemmed palm. Minor forest produce consists of fruits, gums, and grass.

The only mineral known to occur in Kolaba is iron, of which traces are found in laterite in different parts of the District. Aluminium occurs in the form of transcite in the hills around Matheran. Good building stone is everywhere abundant ; sand is plentiful in the rivers ; and lime, both nodular and from shells, is burnt in small quantities.

[edit] Trade and communications

Salt is extensively made by evaporation, and its production furnishes profitable employment in the fair season, when the cultivators are not engaged in agriculture. It is produced in large quan- ties in the Pen and Panvel s, but the Pen trade is falling off. The District contains 155 salt- works, which produce nearly 2 ½ million maunds of salt yearly. The weav- ing of silk, a relic of Portuguese times, is practised at Chaul ; but the manufacture has declined since 1668, about which time a migration of weavers took place and the first street was built in Bombay to receive them. The extraction of oil from sesamum, the coco-nut, and the ground-nut, and the preparation of coco-nut fibre, also support many families. The manufacture of cart-wheels at Panvel is a large industry. 1 This figure is taken from the Forest Administration Report for 1903-4. The preparation of spirits, a business entirely in the hands of Parsls, is restricted to Uran, where there are numerous large distilleries.

The principal trade centres of the District are Pen, Panvel, Karjat, Nagothana, Revadanda, Roha, Goregaon, and Mahad. The chief articles of export are rice, salt, firewood, grass, timber, vegetables, fruits, and dried fish. The supply of vegetables of various sorts to Bombay from the Allbag and Panvel s has increased on a remarkably large scale, and also the provision of fuel from the Allbag, Pen, and Roha s. Grass is sent to Bombay in large quantities from the Panvel and Pen s. The imports consist of Malabar teak, brass pots from Poona and Nasik, dates, grain, piece-goods, oil, butter, garlic, potatoes, turmeric, sugar, and molasses. The District appears on the whole to be well supplied with means of transporting and exporting produce, a great portion being within easy reach of water-carriage. There are five seaports in the District. During the ten years ending 1902-3 the total value of sea-borne trade averaged nearly 177 lakhs, being imports about 31 lakhs and exports about 146 lakhs. In 1903-4 the imports were valued at 32 lakhs and the exports at 121 lakhs ; total value, 153 lakhs. Minor markets and fairs are held periodically at thirty places in the District. Banias from Marwar and Gujarat are the chief shopkeepers and money-lenders.

The District is served by the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which passes through the Karjat and the Khalapur petha. In addition to a steamer ferry between Bombay, Dharamtar, and Ulva, there is direct steamer communication for passengers and freight between Bombay and the coast ports during the fair season. There are three main roads over the Bor, the Fitzgerald, and the Varandha ghats, which connect the District with the interior and are available for traffic all the year round. The total length of metalled roads is 87 miles, and of unmetalled roads 160 miles. The Public Works department maintains 78 miles of the former and 85 miles of the latter. Avenues of trees are planted along 37 miles.

The largest bridge is one of 56 spans at Mangaon across the Nizam- pur-Kal. At Nagothana there is a masonry bridge, built in 1580 at a cost of 3 lakhs to facilitate the march of the Ahmadnagar king's troops into Chaul.

[edit] Famine

The oldest scarcity of which local memory remains was the famine of 1803. The distress caused by want of rain and failure of crops was in- creased by the influx of starving people from the Deccan. Many children are said to have been sold for food. The price of rice rose to about a seer for a rupee. To relieve distress, entire remissions of revenue, during periods varying from eight months to two years, were granted. In 181 7-8 there was a great scarcity of food, approaching to a famine. In 1848, in the old Sankshi division, part of the rice crop on saline land was damaged by unusually high spring- tides. Remissions were granted to the amount of Rs. 37,750. In 1852 heavy rain damaged grain and other produce stacked in the fields. In 1854 an exceedingly good harvest was the outcome of a most favour- able rainfall ; but on November 1 a terrible hurricane completely destroyed every sort of field produce, whether standing or stacked, felling also coco-nut and areca-nut plantations. Remissions to the amount of more than Rs. 12,000 were granted. In 187 1 there was a serious drought, particularly in the southern half of the District. In 1875-6 and in 1876-7 floods did much damage to the same tract. In 1878-9 the cold-season crops were damaged by locusts.

[edit] Administration

The District is divided into seven tahikas, Alibag, Pen, Panvel, Karjat, Roha, Mangaon, and Mahad, usually in charge of one member of the Indian Civil Service and a Deputy- Collector recruited in India. The Khalapur, Uran or Karanja, and Nagothana pethas are included in the Karjat, Panvel, and Pen tahikas. The Collector is ex-officio Political Agent for the JanjTra State.

The District is under the sessions division of Thana, and the District Judge of Thana disposes of civil appeals from Kolaba. During the monsoon the District Magistrate is invested with the powers of a Sessions Judge. There are five Subordinate Judges. The District Judge of Thana acts as a court of appeal from the Subordinate Judges, who decide all original suits, except those in which Government is a party and applications under special Acts. There are twenty-five officers to administer criminal justice. The commonest form of crime is petty theft; but cases of homicide, hurt, and rioting occasionally occur and are usually ascribable in the first instance to drink, to which a large majority of the population are addicted. In years of scarcity dacoities are sometimes committed by immigrants from the Deccan ; but as a rule this form of crime is unknown.

The District was first included in Ratnagiri and then in Thana. In 1853 it was made a sub-collectorate and in 1869 a separate District. After annexation in 1818, the practice of paying revenue in grain was for some time continued j and during the period of depressions in prices, 1823-34, the District fared better than Thana, where money payments were taken. From 1834 to 1854 the country improved, population increased, and reductions were made in the Government demand. Between 1854 and 1866 survey rates were introduced, and as this occurred in some parts before the rapid rise of prices in that period, the cultivators became extremely prosperous. Other parts were settled under the influence of high prices, and for a time their condition was depressed, but on the whole cultivation and revenue have both advanced. The revision survey settlement was carried out in the whole of the District between 1889 and 1904. The revision found an increase in the cultivated area of 0-3 per cent, and enhanced the total revenue from 11 to 13 lakhs. The average assessment per acre of 'dry' land is 5 annas, of rice land Rs. 4-1 1, of garden land Rs. 9-8.

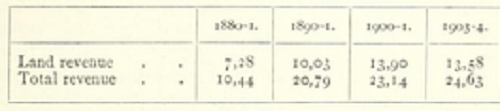

Collections on account of land revenue and revenue from all sources have been, in thousands of rupees : —

A peculiarity of Kolaba District is the khoti tenure, which exists in 445 villages. The khot was originally a mere farmer of the revenue from year to year, but this right to act as middleman became hereditary, although there was no proprietary right. Under the settlement, the khot, as peasant proprietor, pays the survey rates, while the actual cultivators pay rent to the khot, not exceeding an excess of 50 per cent, above the Government demand, which constitutes the profit of the khot. Most of the present khots are representatives of the original farmers, but in some cases they have sold or mortgaged their rights.

The District has seven municipalities : namely, Alibag, Pen, Roha Ashtami, Mahad, Panvel, Uran, and Matheran. Outside their limits, local affairs are managed by the District board and seven boards. The total receipts in 1903-4 were 1-33 lakhs and the expendi- ture 1-44 lakhs. The principal source of income is the land cess. Over Rs. 52,000 was devoted to the construction and maintenance of roads and buildings.

The police force is under the control of the District Superintendent, assisted by one inspector. There are twelve police stations, with a total of 555 police, including 8 chief constables, 103 head constables, and 444 constables. There are nine subsidiary jails and one lock-up in the District, with accommodation for 230 prisoners. The daily aver- age number of prisoners in 1904 was 24, of whom 2 were females. Kolaba stands thirteenth among the 24 Districts of the Presidency in regard to the literacy of its population, of whom 4-7 per cent. (9 males and 0-3 females) could read and write in 1901. In 1881 the number of schools was 76, with 4,520 pupils. The pupils increased to 9,481 (exclusive of 1,117 m 68 private schools) in 1 891, and further to 11,130 (including 1,256 in 85 private schools) in 1901. In 1903-4 there were 242 schools attended by 9,277 pupils, including 1,021 girls. Of the 193 institutions classed as public, one is a high school, 188 are primary, and 4 middle schools ; 139 are managed by the District board, 24 by municipalities, and 30 are aided. The total expenditure on education

in 1903-4 was Rs. 87,000, of which Rs. 16,000 was derived from fees.

Of the total, 83 per cent, was devoted to primary schools.

The District contains 2 hospitals and 6 dispensaries, with accommo- dation for 52 persons. In these institutions 62,000 cases, including 178 in-patients, were treated in 1904, and 902 operations were per- formed. The expenditure was Rs. 18,500, of which nearly Rs. 9,300 was met from Local and municipal funds. The number of persons successfully vaccinated in 1903-4 was 14,573, representing a proportion of 24 per 1,000 of population, which is slightly below the average of the Presidency.

[Sir J. M. Campbell, Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, vol. vi (1883) ; Major J. Francis, Settlement Report of the Kolaba District (1863).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.