E-commerce, M-commerce: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

“India Today”

Laws, rules

E-commerce intermediaries not liable for vendors’ actions: HC

Vasanth Kumar, January 10, 2021: The Times of India

In what could be a shot in the arm for ecommerce platforms, the Karnataka high court has said that an intermediary governed by Information Technology Act, or its directors/ officers, would not be liable for any action or inaction on the part of a vendor/seller, who makes use of its website or marketplace facility.

The HC made this observation on January 7 while quashing a complaint as well as proceedings against Snapdeal Private Limited and two of its directors. The court said it cannot be expected that the provider or enabler of the online marketplace is aware of all the products sold on its website.

“It is only required that such provider or enabler put in place a robust system to inform all sellers on its platform of their responsibilities and obligations under applicable laws to discharge its role and obligation as an intermediary. If the same is violated by the sellers of goods or service, they can be proceeded with, but not the intermediary,” Justice Suraj Govindaraj stated.

The complaint against Snapdeal, filed by the Mysuru drugs inspector before the CJM court in June 2020, was related to selling Suhagra-100 tablets (sildenafil citrate tablets 100 mg) between October 13, 2014 and December 16, 2014. M/s Adept Biocare, a Haryanabased company, had on November 20, 2014 sold 100 tablets to one Manjunath through the seller account created by it on Snapdeal. Snapdeal challenged the court’s summons in the HC, where Govindaraj, pointing to the inordinate delay of six years in filing of the complaint, said “neither Snapdeal or its directors can be prosecuted for the offence”.

E-tailers must pay sellers in 2 days: RBI

Digbijay Mishra, E-tailers must settle seller payments in 2 days: RBI, October 9, 2017: The Times of India E-commerce players have been mandated to clear payments of merchants within two days of intimation regarding the completion of transaction, the RBI has said in response to a query sent by an online seller. The central bank's response, reviewed by TOI, makes it clear that completion of transaction means the act of making the payment. Every e-commerce company has its own agreement with sellers about intimation regarding the completion of a transaction. Although typically , it is referred to as date of dispatch. At present, however, the majority of e-commerce companies take a week to 15 days to settle payments of sellers. Flipkart, for instance, has a 7-12 day cycle for various categories of sellers, including gold and silver retailers.

Sellers on multiple e-com merce platforms say leading etailers are not settling payments for prepaid orders according to the RBI regulations and they usually take about a week on an average. When contacted, an Amazon spokesperson said the company was compliant with the regulations. A Flipkart spokesperson declined to comment.

E-tailers charge a payment collection fee from sellers for both online payments and cash on delivery orders.

History/ evolution on online shopping

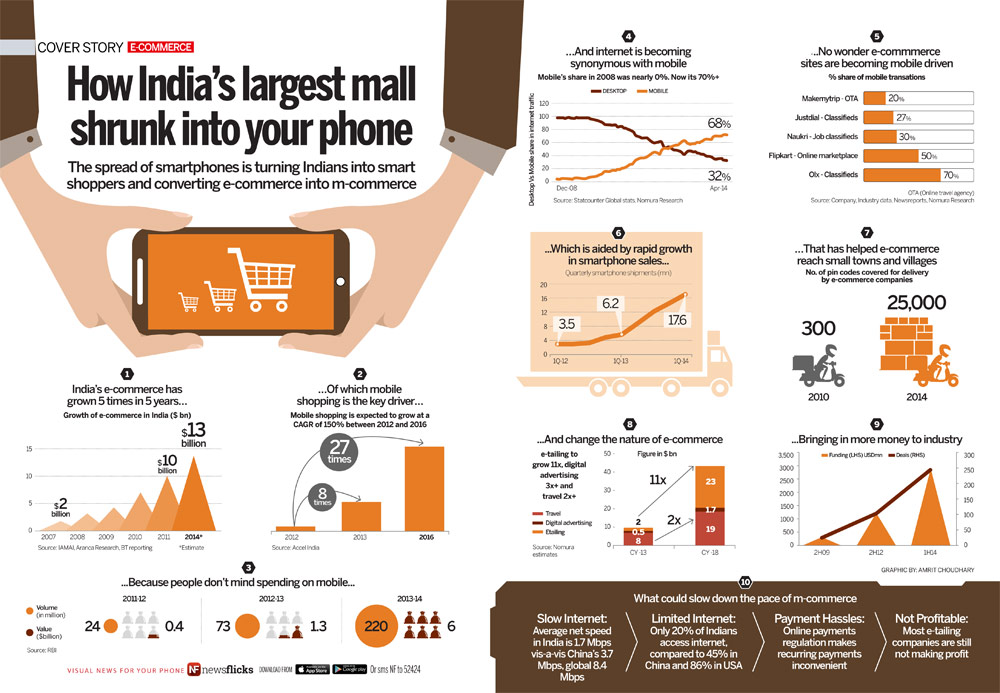

The spread of smartphones changes shopping

The spread of smartphones is turning Indians into smart shoppers and converting e-commerce into m-commerce.

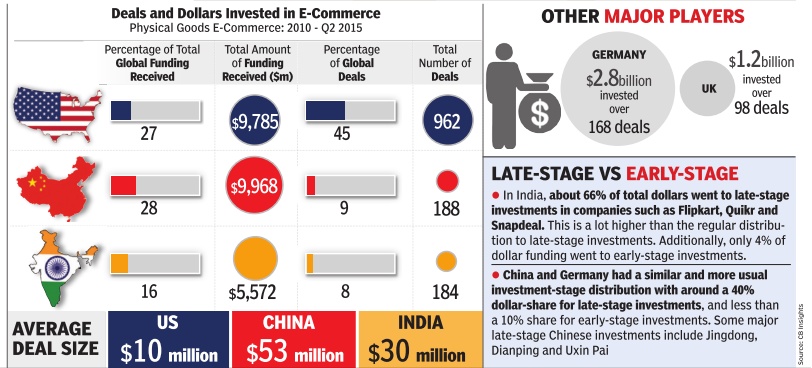

Deals in E-commerce, US, China and India, 2012-15

See graphic:

Deals in E-commerce, US, China and India, 2012-15

2013-17: India, the fastest growing e-comm market

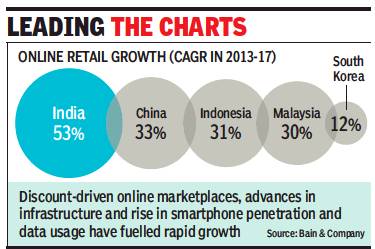

India is fastest growing e-comm mkt: Report, November 29, 2018: The Times of India

From: India is fastest growing e-comm mkt: Report, November 29, 2018: The Times of India

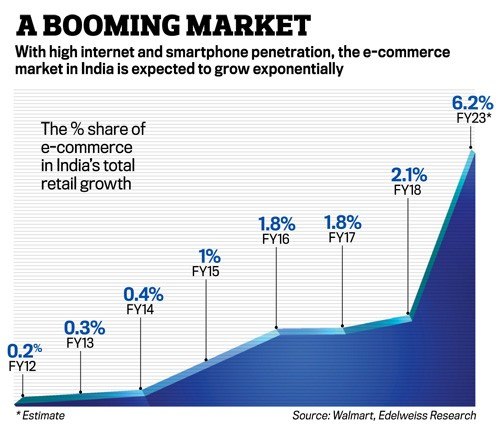

India has the fastest growing online retail market among top global economies. The country’s online retail market witnessed a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 53% for the period 2013 to 2017, according to a latest report by consultancy firm Bain & Company.

The rapid growth, albeit over a small base, has been driven by aggressive discount-driven e-commerce marketplaces, advances in delivery infrastructure and increased smartphone penetration and data usage.

These conditions are giving rise to large retail ecosystems. “What we’re seeing is the emergence of scale open retail ecosystem platforms across the Asia Pacific region that offer retailers a compelling alternative to building and scaling their own capabilities,” said Melanie Sanders, partner at Bain & Company.

Retail ecosystems comprise communities of consumers, retailers and partners that rapidly reshape the retail landscape. They deliver a very sticky consumer proposition by combining services like e-commerce, chat, streaming, gaming or payments in a single platform or app, which shoppers are adopting globally, the report said.

While Alibaba and Tencent lead the best-known Asian ecosystems, India too is witnessing the emergence of retail eco-systems, led by Reliance, Flipkart/Walmart,Amazon/Future Group and Alibaba.

India’s total e-commerce retail sales in 2017 were pegged at around $20 billion and studies have indicated that another $50 billion of online e-commerce could be unlocked by adding new users and luring back internet users that do not currently shop online due to various reasons.

Despite the rapid growth, online retail penetration in India is low at 5% compared with markets such as China (20%) and the US (12%). India was ranked eighth in terms of online retail penetration among 11 countries.

Consumer electronics segment in India has the highest online penetration (17%, which is e-commerce sales as percentage of total retail sales) followed by apparel and footwear (9%) and beauty and personal care (1%). Food & grocery, with overall retail sales of around $530 billion in 2017, has one of the lowest online penetrations at 0.1%.

2014-16: change in three major trends

Samidha Sharma, How India's e-shopping has changed, Oct 09 2016 : The Times of India

THREE TRENDS THAT SHOW HOW - INDIA'S E-SHOPPING HAS CHANGED

This festival season is seeing the rise of a new breed of e-shopper who's as cool about shopping for a smart TV as for dal and detergent

Two years ago in 2014 when Flipkart, the country's largest web retailer kicked off its first flagship Big Billion Day sale, things didn't quite go as per plan. The e-tailer wasn't able to handle the unprecedented traffic and its founders were left apologising to disgruntled shoppers for the snafus. A lot has changed since then, not only for Flipkart and for all e-commerce players, but also in the way India shops online.

Beyond the intense fight for capturing market share emblematic of the e-commerce sector, which reaches fever pitch this time of the year, what's starting to emerge is a breed of seasoned shoppers who is as comfortable shopping for an expensive smart TV as ordering their dal-detergent online.

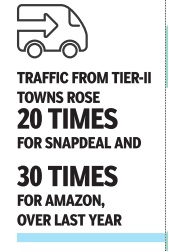

Small-Town India Becomes Big Online

If we were to believe data from companies, online retail's march into smaller Indian cities seemed to have finally made progress this year after many attempts to amp up business from these towns. What'll be interesting to watch is if these numbers sustain. Amit Agarwal, country head of Amazon India, says among the 15 million units it sold during its `Great Indian Festival', orders came from 90% of India's pin codes. The number of new customers increased five-fold over last Diwali with 70% of new shoppers coming from tier II and tier III towns, he adds. Overall, 65% of Amazon's orders come from towns categorized as tier II (population of one million) and below. Rival Flipkart says sales from tier II and below cities went up to 42% from 34% in the past one year.

Even as e-tailers tout their strides beyond the big cities, estimates say the number of online buyers remained at around 68 million in 2016 and majority of them came from metros. “It's true that a big chunk of new customers are from tier II and tier III but their ticket sizes and frequency of purchases will take some time to increase as most of them are only shopping because of discounts,“ says Satish Meena, forecast analyst at Forrester Research.

A good part of the sales during the festive season typically comes from incremental wallet share of existing buyers. The market expansion due to new shoppers is still limited, he says.

But not for want of trying. To boost the e-tailing market which has stuttered in the past year, having remained at $10 billion in size after galloping at 400% growth the previous year, companies brought in attractive EMI and exchange schemes on electronics and white goods. Membership programmes like Amazon Prime were aimed at locking in customers on to online platforms.

Flipkart's co-founder & CEO Binny Bansal says the average order size is up 20% despite discounts compared to regular days. The e-tailer says it also brought in 1.5 million new customers this year versus one million that came on board last year even as cash-on-delivery (COD) orders came down from 70% to 60% of all Big Billion Day transactions.The decline in COD shows that more Indians now trust online platforms to deliver the goods.

Size And Price No Bar For Buyers

Mobile phones still account for a huge chunk of sales but there's been a palpable focus on high-ticket categories like white goods and large appliances. Devita Saraf, CEO of Vu Television, a brand which sells more than 60% of its products online at an average price point of Rs 25,000, says there's an emergence of a new kind of customer who is online-first in their shopping behaviour. She says her brand was among the top sellers on Flipkart during the five-day sale.

Amazon was seen pushing daily consumables heavily, a first during the sale season which is defined by deals on mobiles and electronics. During the five-day sale consumers were looking for deals on everyday use products like detergents, diapers, grocery and household products indicating that they did not forget their everyday purchases while shopping for other deals, the company says.

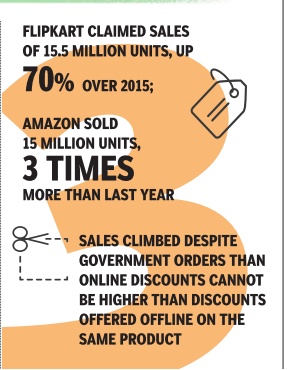

Less Discounting, More Sales?

Post March this year, most e-tailers reduced promotional campaigns after the Indian government introduced new policy guidelines which outlawed online marketplaces from offering discounts directly. While companies did eventually find ways to get around the re gulation, this year's sales haven't offered the kind of deep discounting as previous years. But despite that, volumes are up. Consumers are getting used to buying online more with over 20-25% of users now making a purchase once in two months, says Sahil Barua, co-founder and CEO of e-commerce logistics startup Delhivery .

Radhika Aggarwal, co-founder and CBO, ShopClues, sees this as a sign of the Indian ecommerce market maturing. “E-commerce was built on discounts to change consumer behaviour as there were no other hooks at the time.But now people wait for the sales because of the kind of selection of products they find online,“ she says. What happens post the sale-month spike will be decisive in understanding if the overall market has grown spawning new buyers or the growth was just seasonal.

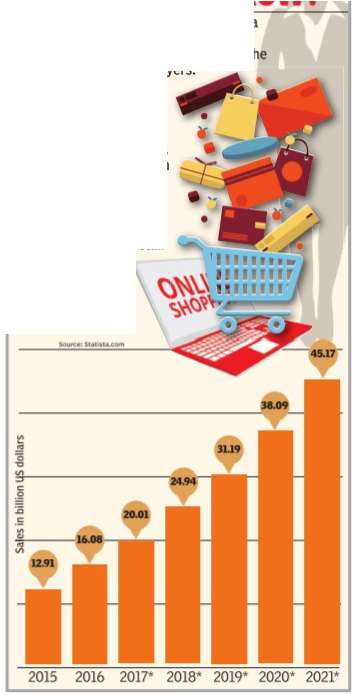

2017-2022

See graphic.

Background/ profile of online shoppers

70% of new customers from tier II & III towns/ 2016

70% of new customers from tier II & III towns, says Amazon, Oct 03 2016 : The Times of India

After a year of tepid online retail sales, etailers like Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal witnessed a wave of consumers flocking to their platforms as the much-publicised annual festive season sale kicked off over the weekend.

Interestingly, a significant chunk of the new online shoppers is reported to have come from smaller towns in states like Sikkim, Tripura and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. These towns are a potentially huge market that online retailers are eyeing to expand the overall ecommerce pie, which has largely failed to grow over the past year. For the Seattle-based Amazon, traffic from tier II and tier III towns increased 17 times compared with last year indicative of how discounting has aided the entry of a new se of buyers. The top six-eight citi es typically contribute 90% of sales for all the consumer inter net players, leaving a yawning gap between these markets and the still largely untapped smal ler towns.

Manish Tiwary , VP , catego ry management at Amazon In dia, said, “We have seen a five fold growth in new customer ac quisition and 70% of them ca me from tier II & III towns.“

While Flipkart and Snapdea are still to detail the growth in number of shoppers from smal ler towns, Shopclues claimed to have notched up double of the business from last year with a significant rise in traffic co ming from users in tier II cities.

A Google trends report sha red by Shopclues, which posi tions itself as targeting markets outside of metros, said these cus tomers searched for “online shopping“ in the run up to the annual sale event. “Every consu mer is a deal seeker and during such events it is likely that users from smaller towns will come to these sites. A lot of it is channe led by rising smartphone penet ration,“ said Arvind K Singhal ,chairman at Technopak, retai advisory firm.

The country's largest e-tai ler Flipkart, which began its an nual Big Billion Days sale on Sunday , claimed to have sold half a million units within the first hour of the event. Amazon, which started its sale on Satur day, said it registered a billion hits on the first day, clocking 1.5 million units in the first 12 ho urs. Delhi-based Snapdeal claimed it was getting 180 orders per second in the first half and it ended up with 11 lakh buyers purchasing on its platform in the first 16 hours, registering a sixfold growth in sales volume.

“We have seen a three-time growth on day one compared with last year. The trend is that we are outpacing Saturday's sale on Sunday which is unusual because traditionally sales are lower on day two of most sale events,“ Tiwary said, adding that smartphones have been the biggest grosser for Amazon. Television sales, usually most popular during the festive season, grew 25 times on the back of exclusive partnerships with the likes of Sanyo.

For Flipkart, which is locked in a battle with Amazon for the leadership position, the number of large LED TVs sold in six hours was higher than the total number of TVs sold during The Big Billion Days last year . The Flipkart-owned Myntra saw its revenues increasing three times in the first hour compared with last year . “What makes it special is that the number of units sold in the first six hours of sale surpassed the total units sold in a day during the first day of Big Billion Days in 2015,“ said Kalyan Krishnamurthy , head, category design organisation, Flipkart. Both Flipkart and Amazon are investing aggressively to garner as much market share during the annual sale event on the back of discounts and the promise of faster services and better user experience.

Business practices

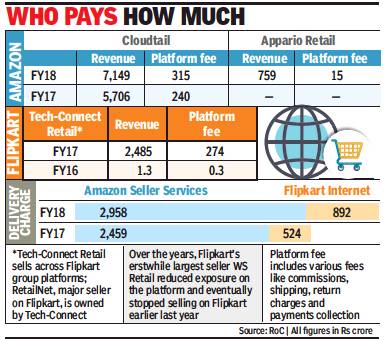

Large sellers pay much less as platform fee

From: Digbijay Mishra, Biggies pay lower online platform fee than small cos, January 7, 2019: The Times of India

‘E-Commerce Players Favour Alpha Sellers’

Large online sellers who have affiliations or investments from e-tailers like Amazon and Flipkart are paying only about 5-11% of their revenue as marketplace fee, while regular third-party sellers typically pay at least 15% as platform fee.

The latest balance sheets of major online sellers like Cloudtail, Appario Retail, and Tech-Connect Retail show the amount they pay as platform fee to online marketplaces. Cloudtail paid Rs 315 crore as platform fee to Amazon on a revenue of Rs 7,149 crore in FY2018. That’s 4.4%. It’s about 11% for Tech-Connect Retail, which owns one of the largest sellers on Flipkart, RetailNet. These entities drive large volumes of sale for companies like Amazon and Flipkart.

Small third-party sellers have frequently alleged that e-commerce players favour these alpha sellers on their platforms. This is among the reasons that persuaded the government recently to issue a circular stating that sellers that have direct or indirect investment from the e-commerce platforms cannot sell on these platforms.

Industry sources also say that these platforms are subsidising the logistics spends of the big sellers. They point to the rising spends on delivery—or ‘logistics service charge’—for these platforms in the last two financial years. The annual reports of the entities that run Flipkart and Amazon’s marketplaces show these spends are increasing, but do not give specific details on them.

When contacted on these figures, Amazon India did not respond to the queries. Flipkart said: “We have several tiers that sellers are classified into on the basis of several metrics such as business volume, number of returns, customer experience and satisfaction, etc. Commissions, fees, value added services like logistics etc, are priced based on the tier a seller is in. We provide them with the tools and support to help them grow and to climb the tiers.”

Previously, online seller associations like AIOVA have raised these issues with government and authorities such as the Competition Commission of India (CCI). Both Flipkart and Amazon have maintained they do not treat third party sellers in a biased manner.

The new FDI rules are an attempt to comfort small traders. The timing of the policy change is being linked to the general elections later in the year. E-tailers are trying to come up with new structures that will allow them to continue with their operations with the least possible impact on revenue.

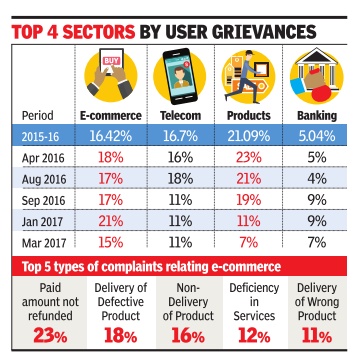

Complaints against e-commerce companies

2014-Dec 16, an increase of more than 300%

E-comm plaints up by 300% in 3 yrs, Feb 3, 2017: The Times of India

The number of complaints against e-commerce companies has increased by more than 300% during the past three years, the government told the Lok Sabha. This points to the need for a robust mechanism to deal with such complaints in view of the government's thrust for digitisation and more and more people shopping online.

Quoting the number of complaints received by the National Consumer Helpline (NCH), minister of state for consumer affairs C R Chaudhary submitted that the provi sions of the Consumer Protection Act cover all goods and services, including e-commerce. The NCH data show while had received only 418 compla it had received only 418 complaints relating to e-commerce in 2014-15, the number increased to 1,386 in 2016-17 (till December end). NCH has received complaints against some popular entities, including Paytm, Snapdeal, Amazon, Flipkart, eBay , Myantra and Jabong.

“A consumer can file a complaint relating to e-commerce transactions in the appropriate consumer forum established under the Act,“ Chaudhary said. He also said that before approaching a consumer forum, complainants can use alternative dispute resolution mechanism through the NCH and Online Consumer Mediation Centre in the National Law School, Bengaluru.

Complaints against e-commerce companies/ 2017

list 15% Of All Plaints Against Shopping Sites

As more Indians flock to the the internet to shop for their daily needs, complaints are building up about e-commerce companies.

The National Consumer Helpline (NCH), a joint initiative of the consumer affairs department and Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), receives about 3.5 lakh grievances annually.

This is only a fraction of the complaints registered by consumers, as there are other avenues for dispute redressal, including the consumer approaching the companies directly. But NCH said complaints relating to e-commerce overtook all other sectors since September.

“Due to increased penetration of internet and more companies pushing for online sale of their products, the number of complaints has also increased,“ said Prof Suresh Misra of IIPA. “We have tied up with 35 e-commerce companies for faster resolution of complaints and it's doing well,“ he added.

E-commerce received the highest number of com plaints this year, of the total complaints received by NCH.

Most complaints against e-commerce companies were related to “paid amount not refunded“, according to data provided by NCH. Makemytrip, the country's largest online travel agent, agreed.

“Issues like customer requesting for full refund for airline tickets due to a personal emergency takes a while as it requires us to go to our partners for special waivers,“ said a Makemytrip spokesperson.

Most companies attributed the rising number of consumer calls to requests for cancellation and not complaints.

The rising number of consumer grievances has not gone unnoticed by the government. In June 2016, PM Modi had flagged concerns over the large number of consumer complaints relating to e-commerce including booking of tickets and hotel reservations. He had asked officials for a review of the nature of issues and had asked the consumer affairs ministry to list the number of complaints against each company .

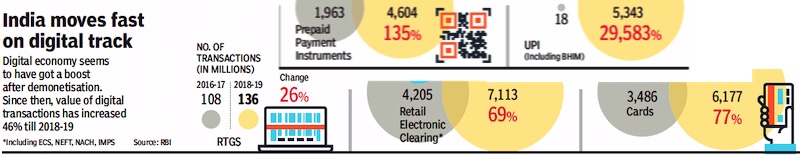

Digital transactions

2016-19

From: July 17, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic, ‘Digital transactions in India, 2016-19 ’

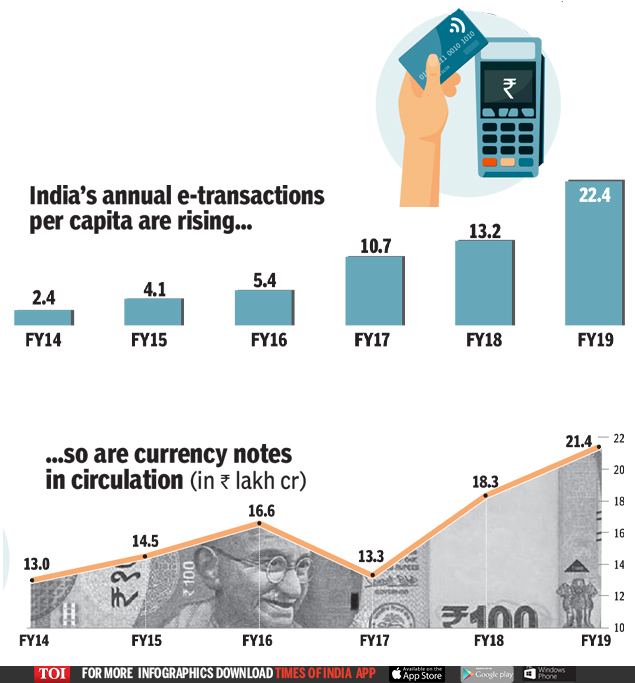

2014-19: E- transactions vs. currency in circulation

August 20, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 20, 2019: The Times of India

In India, digital payments have climbed five times since FY15 to 22.4 transactions per person in FY19. However, coverage remains a problem. For instance, the user base of account-to-account funds transfer platform Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is only 100 million, or less than 8% of the population. And cash still rules: As a proportion of GDP, cash has been rising in the past 2 years, hitting a 3-year high of 11.3% in FY19.

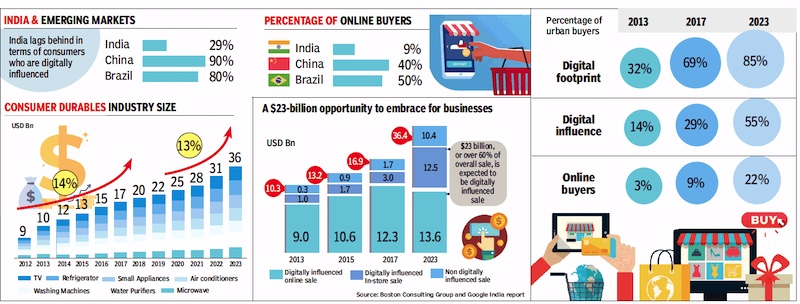

2012-23

From: August 5, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Digital penetration in India, 2012-23 (projected)

Digital wallets, digital payments, Mobile banking, UPI: India

See Digital wallets, digital payments, Mobile banking, UPI: India

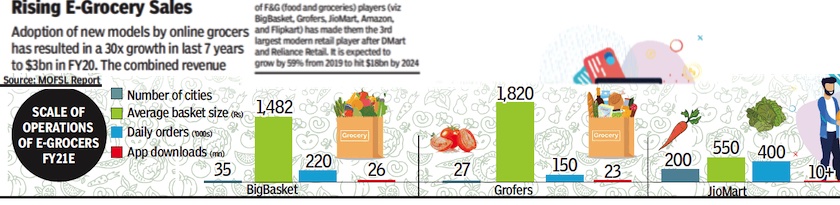

E-grocery

2021

From: June 11, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Scale of operations of E-grocers FY 21E

Food ordered online

2015: Kolkata, Delhi top Zomato survey

The Times of India Jan 02 2016

Rachel Chitra

The bhadralok of West Bengal, known for their discerning palate and robust appetite, lead the country with the biggest online food orders, at an average order size of Rs 690, a survey by Zomato shows.

Delhi comes second -at Rs 640 -but pulls off the high est single-value order at Rs 21,500. The food portal did not name the customer, though.

The other cities down the list are Hyderabad (Rs 625), Bengaluru (Rs 540) and Chennai (Rs 500); Mumbai (Rs 490) and Pune (Rs 450) draw up the end. Chicken biryani, burgers, butter chicken, pizza and hakka noodles are customers' most preferred orders.

Overall, north Indian fares on top in the 14-city suvey conducted from May to December 2015, but Chinese, Italian, south Indian and `healthy food' are also popular.

The data shows 86% of customers order from their mobile phones; 53% use Android devices, 29% on iOS handsets and 4% via mobile web gadgets. Only 14% use desktops to order food.

Despite most online payment sites like Paytm and Citrus Pay offering discounts, it is surprising that up to 70% of customers prefer to pay cash on delivery, the data shows. The Indian fondness for a good bargain notwithstanding, big discounts of more than 30% on online food orders actually fail to attract loyal customers, a recent report by food portal Zomato shows. Measuring a six-week retention rate, it found that 43% of repeat customers used discounts of 10% to 15%; 38% used discounts of 20-25% but only 14% made use of steep discounts of 30% or more.

Also, up to 70% of customers preferred to pay cash on delivery despite discounts offered by online payment sites. “It comes from the Indian psyche,“ Travelkhana.com former operations director Siddharth Misra says.“We have an ingrained suspicion of advancing money. So even with the best discounts online you'd still have a long way to go before you can con vince people to pay money ahead of delivery .“

Card payments have nonetheless recorded a growth of 12% to 16 % from September through December, Zomato's data shows.

The fallacy of big discounts is a lesson that not just Zomato learned; TinyOwl and Foodpanda, also clued in, have scaled back their operations. Earlier this week, Food Panda laid off 15% of its workforce and stopped blanket discounts across brands a few months ago.“Deep discounts don't work in the long run because they affect sustainability,“ Misra says.

Thirukumaran Nagarajan, co-founder of online grocery retailer Ninjcart, which boasts 1.18 lakh customers, says his company has stopped offering discounts and now focuses on improving backend operations. “Even though we've stopped offer ing discounts, we are still growing sizeably and receive between 1,200 and 2,000 orders a day ,“ he says.

Suvadip Guin, a software engineer in Bangalore, says Foodpanda and TinyOwl offered discounts of more than 50%. “Add my Patym 10% discount and say a food coupon from Ammi's biriyani or Pizzahut and I can purchase something worth Rs 1,250 for as little as Rs 400,“ he says.

Government e- marketplace (GeM)

2016-18

Digbijay Mishra, December 10, 2018: The Times of India

From: Digbijay Mishra, December 10, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Government e- marketplace (GeM), as in 2018, Dec

GeM was started in 2016 as a platform for online procurement of common goods and services for different central and state government departments, organisations and public sector companies.

Government policies

The changes of 2019

Asit Ranjan Mishra, January 16, 2019:: Livemint

From: Asit Ranjan Mishra, January 16, 2019:: Livemint

The new rules for FDI in e-commerce, to be implemented from 1 February, could throw a spanner in India's thriving online retail sector

In a speech at the All India Traders Convention on 27 February 2014 ahead of the general election, Bharatiya Janata Party’s prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi surprised everybody by not playing to the gallery.

“I don’t know whether I will gain politically or not by saying this," Modi told an audience full of traders, his party’s core vote bank. “Whether you like it or not, we need not be afraid of the global challenges in the business world. We should convert this to opportunity. We should not think that ‘if online trade comes, we will be finished’. You should demand (of) the government how to increase your capability to meet this new global challenge rather than telling the government, ‘shut down online trade’. How will you stop it? We have to accept the modern science and technology. We should not plan to flee, but to fight," Modi said.

Four years later, after extensively liberalizing retail trade, except allowing foreign direct investment (FDI) in multi-brand retail—which was a 2014 manifesto pledge—Modi is showing signs of nervousness. Poll reverses in recent state assembly elections and a resurgent opposition seem to have forced Modi to cosy up to his original voter base, the traders.

On 26 December, a day after Christmas, while festive sales peaked, the department of industrial policy and promotion (DIPP)—the nodal agency for formulating FDI policy—surprised everybody with fresh regulations that could throw a spanner in India’s thriving e-commerce marketplaces. The Modi government allowed 100% FDI under the e-commerce marketplace model but prohibited FDI in inventory based e-commerce. In the first, e-commerce companies act as platforms for vendors to sell their products and in the second, they can sell their own products.

The changes, which will take effect on 1 February, are five-fold: First, marketplace entities cannot buy more than 25% from a single vendor; second, marketplaces will not directly or indirectly give discounts on products; thirdly, entities in which there is equity participation by the marketplace entity cannot sell their products on the platform run by the marketplace; fourthly, e-commerce marketplace entity will not mandate any seller to sell any product exclusively on its platform only; and fifthly, marketplaces will have to submit a compliance report to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) by 30 September every year.

While the first and second criteria were mandated even earlier, the DIPP always looked the other way when they were violated. The latest changes in the policy are widely believed to be a political move ahead of the general election due in April-May to assuage the trading community which has been hit by demonetization and the implementation of the goods and services tax.

Traders were also miffed with the Modi government’s e-commerce policy, as online trading platforms were harming their businesses by providing deep discounts.

India’s $18-billion e-commerce industry initially thrived in a policy vacuum, aggressively funded by venture capital firms. To legitimize the existing businesses of e-commerce companies operating in India, the government in March 2016 through press note 3 (of 2016 series) allowed 100% FDI in online retail of goods and services under the so-called ‘marketplace model’ through the automatic route and notified new regulations. DIPP through its 26 December notification has now added new stringent regulations to the ones existing in press note 3 of 2016.

While the fresh regulations could spoil plans for greater synergy between Flipkart and its new owner Walmart which operates in the cash-and-carry retail space where 100% FDI is permitted like in e-commerce marketplace entities, it also bars Amazon from selling products from subsidiaries like Cloudtail and Appario where it has significant investments. Cloudtail is a joint venture between Amazon and N.R. Narayana Murthy’s Catamaran Ventures.

The move to ban exclusive deals for products also hurts top online retailers such as Flipkart and Amazon. Flipkart, for instance, has exclusive partnerships with top smartphone brands such as Xiaomi and Oppo. Smartphones make up over 50% of e-commerce sales in India.

A DIPP official speaking under condition of anonymity insisted that press note 3 of 2016 only issues a clarification. “We have not formulated any new policy. We have not even gone to the cabinet for a new policy," he said. The department is formulating an e-commerce policy, a draft version of which is expected to be released soon, after a similar draft policy by the commerce department was rejected by e-commerce players.

When asked about the motive behind the clarifications, the DIPP official said: “Marketplace should be a pure marketplace. We hope these steps will ensure establishing a pure marketplace and influencing price will be more difficult," he added.

An official of an e-commerce company speaking under condition of anonymity said the new regulations are draconian and a bigger retrospective move than even the Vodafone tax issue. “It will not only impact e-commerce sector but also FDI inflow in other sectors because regulations can change overnight. The ecosystem is seeking more time for implementation. Under the current political scenario, we don’t expect a review of the regulations immediately. We will have to wait till the election season is over," the official added.

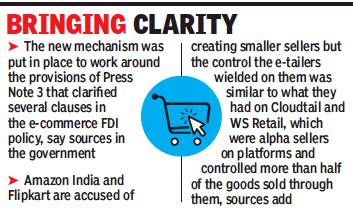

Govt: e-tail majors violated regulations, influenced prices

From: John Sarkar, Govt accuses e-tail giants of violating FDI regulations, February 6, 2019: The Times of India

Says Amazon, Flipkart Influenced Prices, Cos Deny Charges

The government has defended its decision to rework the rules for the marketplace model, accusing the country’s top e-tailers Flipkart and Amazon of operating “hybrid” versions, which were anchored by inventory-based operations through a network of controlled sellers.

This is the first time since the new rules were announced on December 26 that there is clarity on how the e-tailers, who were lobbying at all levels in the government, were “circumventing” the previous rules. Earlier, the government had said it was acting on complaints submitted by several stakeholders.

“Flipkart and Amazon were influencing prices of goods on their platforms through various means, including direct price discounts, covering marketing expenses (marketing campaigns, EMIs, exchange offers) and extending concessional logistics services (packaging, courier, returns), e-wallet cashbacks,” a source told TOI. “Both Flipkart and Amazon involved various intermediaries and group entities in the chain to divide these discounts and spread losses, which impact the domestic retail sector.”

For instance, Amazon Wholesale India would buy branded goods in bulk from manufacturers and allegedly sold to sellers such as Cloudtail, Rocket Kommerce and Green Mobiles at a discount, with the losses shown on its books. Amazon Seller Services is accused of paying for marketing, zero-cost EMIs and some of the other expenses. It would also handle the logisticsrelated activities, with a discount built in. Amazon Pay was also offering cashbacks, which were seen as discounts.

Similarly, Flipkart India allegedly bought goods in bulk, sold it to sellers linked to it such as RetailNet, SuperComNet and OmniTech Retail, Truenet Commerce and India Flash Mart at a discount. Then, Ekart Logistics undertook packaging and shipments, with PhonePe offering cashbacks.

While sources said the operations violated Press Note 3 of 2016, Amazon and Flipkart denied any irregularities. “These comments are completely baseless and untrue. We have received no such communication from the government. We have always been and continue to be compliant with all local laws and regulations,” an Amazon India spokesperson said.

A Flipkart Group spokesperson refused to comment. “The impact on Flipkart seems to be less in the short term but there will be long-term ramifications on its business model due to the tweaks in the policy,” said a company executive.

Several sellers had complained about the practices adopted by e-tailers, which prompted the government to step in, sources said.

Grocery

Physical Stores Offer More Grocery Than E-Tailers: Sachs, 2012

Digbijay Mishra, When offline deals beat online ones, October 4, 2017: The Times of India

Physical Stores Offer More Grocery Discounts Than E-Tailers: Study

Goldman Sachs is slaying the perception that online players like Amazon and BigBasket have outsmarted brickand-mortar retailers with better pricing in daily consumables and groceries. In a recent research report, Goldman Sachs analysts noted that Amazon and BigBasket sold personal care products at 1030% premium compared to traditional supermarkets like D-Mart. The report though predicts online ordering would account for 22% of the modern Indian grocery retailing in five years, up from 3%.

While modern retail is still a small part of overall retail market in India, e-commerce in specific is at a nascent stage. In a bear market, e-commerce could see the highest growth in modern Indian grocery market compared to traditional brick-and-mortar retailers. Traditionally, the grocery play has been a low margin business that requires continuous investments to build a strong supply chain.

“We believe there is an ad ditional cost of about 3-5% of sales for home delivery as compared with pickups from a delivery centre or purchasing from a store. We believe consumers that value convenience over incremental cost will use the home delivery option, while price-sensitive consumers will prefer to pick up the order.Amazon and BigBasket also have the option of express delivery for an additional charge.In our base case, we assume a rapid acceleration in the adoption of online ordering,“ the report noted, while covering Avenue Supermarket, the parent of D-Mart, which offers 10-15% cheaper pricing compared to online grocers.

While D-Mart has presence in132 locations across the country, both BigBasket and Amazon have been ramping up their operations. Amazon, with no worry for capital, has been pushing its grocery business with two products -Pantry and Amazon Now . Pantry , which is for monthly grocery bulk sales, is present in 34 cities and Amazon Now is present in four cities with a promise of a two-hour delivery. BigBasket is delivering across 21 cities with 40,000 orders per day . According to the report, BigBasket accounts for 85% of online grocery market. Kishore Biyani, CEO of Future Group that owns Big Bazaar, said a reason for higher online prices was the mounting pressure on e-commerce players to make profits.“We also have a wide range of products cheaper than many online players. More importantly , they have realised they can't scale grocery business online like other segments and that's why they have gone slow on discounting,“ Biyani added. Murali Krishnan, who recently quit as CEO of Nilgiris, added that traditional retailers have an advantage in logistics compared to the online rivals and that margins are typically about 3-4%. “For brands, the shelf presence created by brick-and-mortar retailers offers more brand awareness than being online -which makes for better negotiations. Online players have figured fashion, electronics as categories but grocery has not seen that yet with the likes of Amazon and others.However, BigBasket has been an exception,“ he added. BigBasket co-founder and CEO Hari Menon told TOI that D-Mart had an advantage of owning the real estate of their stores, which helps their margins.“Their direct sourcing from various FMCG companies and the movement of stock keeping units (SKUs) has helped them further. Not only online grocers but other traditional retailers, too, keep a wider range of SKUs than D-Mart,“ Menon said. An email sent to an Amazon spokesperson did not elicit any response.

About 18-24 months ago, most online grocers were trying to scale up their businesses through the market place model but that did not work out with some forced to shrink their operations. BigBasket is increasingly sourcing from FMCG brands and using its own warehouses.Other companies like Grofers too are trying to do the same. Amazon, too, has partnered with BigBazaar, Spar, and HyperCity for Amazon Now, which promises a two-hour delivery .According to sources, the cart rate (number of products actually sent to consumer compared to original order) for Amazon Now has been about 70-80% since it does not have direct control over the inventory .

India vis-à-vis other countries

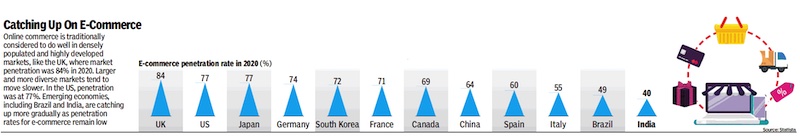

2020

From: February 27, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

E-commerce penetration in India and the world, 2020

Indigenous e-commerce peaks in Dec 15; Amazon closes in

The Times of India, Jun 27 2016

Samidha Sharma

Indian e-commerce cart hits a plateau

Behind numerous headlines of a cash crunch hit ting major Indian ecommerce companies, and commerce companies, and their valuations being questioned, is a revelation not too many people are talking about. Indian e-commerce was emblematic of frenetic growth until very recently , but the last six to eight months have seen the industry come to a grinding halt, making it an inflection point for all the players involved. TOI accessed and analysed data for top e-tailers, which revealed that the online retail market stagnated between May 2015 and 2016 in terms of the value of goods sold. While in May 2015, the e-commerce biggies clocked a gross merchandise value, or GMV , run rate of $9 billion, that number has only inched up to about $10 billion at the end of May this year, translating into an 11% annual growth. In December 2015, the total GMV run rate had reached $10.5 billion on the back of the festive season, which typically sees a rush of discounting from all e-tailers.

GMV is overall sales on an online marketplace, excluding discounts and returns which are an integral part of the e-commerce market.

The data gleaned from primary research and vetted by multiple stakeholders in the industry indicated that Flipkart, the country's largest online retail player, has seen its GMV run rate stall at about $4 billion for almost a year, while an aggressive Amazon has gone from clocking $1 billion to $2.7 billion in gross sales. However, Amazon's operations in India only began three years ago and it's been gaining ground on a smaller base.What's worth noting is that Flipkart notched up a 400% growth the year before, when it's GMV zoomed from $1 billion to $4 billion, post which the numbers have gone flat.Gurgaon-based Snapdeal, on the other hand, has seen an almost 50% knock-down in sales numbers after similar highs it touched exactly a year ago. The company said as of June, its GMV run rate was more than $2.5 billion.

An email sent to Flipkart's spokesperson did not elicit a response till the time of going to press. In an earlier interaction with TOI, Amit Agarwal, Amazon's India head, had said the online retailer hadn't witnessed any signs of a slowdown and, instead, had grown shipments impressively at 150% in the first quarter of the calendar year.

E-commerce companies earn anywhere between 5% and 15% in commission from sellers, which makes up their revenue. GMV had been the key metric for all e-tai lers in India to show rapid growth and ratchet up their valuations in multi-billiondollar fund-raises over the past two years. But with sales staying flat or declining, most e-commerce players are now starting to focus on returning customers, which their founders keep stressing in media interactions.GMV run rate varied from month to month and is pretty jagged, depending on promotions and discounts that are available at the time. But the data collated by TOI points to a palpable slowdown for the first time after a heady period of growth.

Reduced Discounting Slowing Growth?

Post March 2016, most etailers have reduced promotional campaigns after the Indian government introdu ced new policy guidelines for online marketplaces. The fresh rules prohibit online retailers from offering discounts directly . Cash burn for Amazon, for instance, had risen up to almost $80-90 million per month in the early part of the year -more than double of Flipkart's -but has since stabilized, people privy to the matter said.Amazon's Agarwal, when asked about it recently, did not give details on the mounting cash burn involved in weaning away Indian consumers from rivals.

An investor who has been tracking e-commerce says if the market has momentarily stopped growing, it's because online players have reduced investments into market development. A slug of risk capital came into India's online commerce industry , with Flipkart leading the pack. Founded in 2007 as an online bookstore, the Bengaluru-based poster boy of India's thriving startup ecosystem scooped up $3.2 billion, a majority of the funding coming over the past two years, while Snapdeal collected $1.3 billion. The Jeff Bezos-led Amazon, too, has been pumping billions into India, the latest being a $3-billion investment announcement -taking its overall commitment for the country to $5 billion in three years of launching here.

Has Online Consumer Base Capped Out?

India's online shopping market, according to rough esti mates, is 60-70 million, and is expected to go up to 100 million in the next few years. A notable spike happened in the past three years, but the divide between tier I and tier II cities is still very wide. The top 6-8 cities contribute 90% of sales for all the consumer internet players, including app-based cab aggregators like Ola and Uber.

In an earlier interaction with TOI, Binny Bansal, cofounder & CEO, Flipkart, said the e-commerce major was keenly looking at ways to tap into its existing base of users. “There are 50-60 million consumers buying online today . Given the large base, it makes sense to ensure you are selling more to the same customers as that opportunity is big enough compared to three years back,“ he had said. Snapdeal's co-founder & CEO Kunal Bahl, too, has reiterated his focus on the e-tailer's high-value consumers, suggesting GMV was not the metric his company was chasing anymore. “Our GMV run rate continues to be healthy and above $2.5 billion.We are significantly focused on delivering the best experience, growing our net revenue which has increased three times in the last 12 months,“ a Snapdeal spokesperson said in an emailed response to TOI. GMV was described by many as a vanity metric during the past few years when e-commerce registered exponential growth.

“The moment of reckoning is coming or may have come already for Indian ecommerce companies. The ease with which these companies have been able to raise money from VCs may have made them all sloppy , and the test then will be which ones can now work on the `building-a-business' channel. As for whether the fault lies with Indian consumers for not jumping fast enough onto the online wagon, it is a chicken-and-the-egg problem that we have to deal with,“ says Aswath Damodaran, professor of finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University .

What all of this will mean for online retailers is that from here on, raising new capital at present valuations will be a very tough proposition. Flipkart has been conserving cash and has substantially brought down its burn rate to wade through this phase of slow growth.Besides Amazon, there's Alibaba stitching up plans for a direct entry into e-commerce, making it a contest between the two global powerhouses and the Indian incumbents. The next one year will be extremely significant for the local online retailers as they go back to the basics and try to make their businesses self-sustaining while moving towards a tough path to profitability.

Homemakers earn $9bn through social media

Digbijay Mishra, Homemakers clock $9bn biz through social media, June 1, 2017: The Times of India

Puja Singh used to run an in dependent apparel store for 10 years but had to shut shop as she moved from Hyderabad to Bokaro. She never went back to opening another physical store; instead, she opted to sell her wares using WhatsApp and Facebook, as a re-seller.

Many Indian women like Singh are using social media to ride the e-comm wave and reach customers. A report by consulting firm Zinnnov shared exclusively with TOI says 2 million homemakers are clocking business worth $8-9 billion in gross sales by reselling lifestyle and clothing products using the two social media platforms. While e-commerce ma jors like Flipkart and Amazon hog the limelight with their transaction volumes, these homemakers, using basic internet tools, are projected to touch anywhere between $48-60 billion in gross sales by 2022, the Zinnov report pointed out.Online re-sellers typically use WhatsApp and FB to market their products after sourcing them from suppliers who typically keep a bigger stock of products.

The re-sellers then make 15-20% of the order value as commission for selling these products.

Singh says she sells anywhere between 70-80 units of clothing every month and has managed to get buyers from outside her state leveraging the reach of WhatsApp.“As many as 70% of my products are sold locally but I am getting order requests from other Indian cities. Based on the initial success, I plan to sell other categories as well,“ she says.

Just like Singh in Bokaro, Nidhi Jain in Jaipur started her own retail business as a supplier using these social media channels. “I used to take small orders from other suppliers to resell but that has changed with my growing network resulting in higher sales. WhatsApp is mostly used for payments and logistics, but the expansion of consumer base and product discovery is largely through Facebook,“ Jain says. Meesho, a Y Combinator startup, which offers tools to such women to help them start their businesses through WhatsApp and Facebook, says it's banking on the mammoth opportunity this segment presents here in India.“We are not looking for revenues from this set of sellers.The fact that such a market has been created already with two million active re-sellers shows the potential of the opportunity ,“ says Vidit Aatrey, founder and chief executive of Meesho. The total market for women re-sellers is expected grow at 40-50% annually for the next five years. This means it would be over 5% of India's total retail market, he avers.

What's aiding the growth of these re-sellers is the increased usage and access of smartphones in tier-1 cities, which make up 50-60% of the market, while tier-2 and tier-3 cities contribute the rest.Most of these sellers currently use net-banking options and digital wallets for facilitating payments as they compete with bigger online commerce players -which have a gamut of payments options for consumers. Looking at the growing base of re-sellers WhatsApp has been exploring options to start its own payments platform in India.

“I have always been in Jaipur and used to work in an education institute. Though the job wasn't bad, I would prefer to do be my own boss. My business is growing which is why I'm planning to scale it up steadily ,“ Jain says.

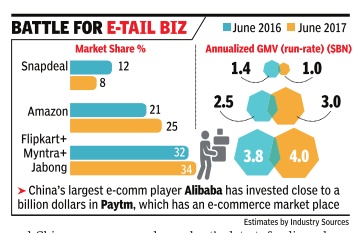

See graphic:

The market-shares of the three main e commerce players in India in 2016, 2017

The market, size of

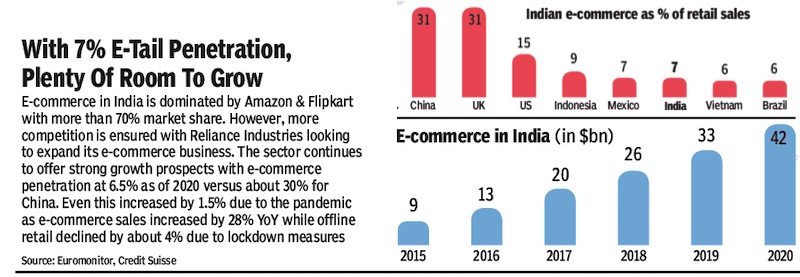

2015-2020

From: April 5, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

The size of the Indian E-commerce market, 2015-2020

National Payments Corporation of India

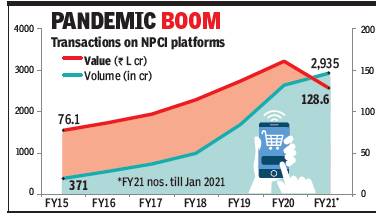

2015-21

From: February 19, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Transactions on NPCI platforms, 2015-21

Trends, shopping habits

2019

Avik Das, Dec, 20, 2019 Times of India

From: Avik Das, Dec, 20, 2019 Times of India

Indian men are more avid shoppers of clothing online than women, according to market research firm Nielsen’s maiden report on shoppers’ behaviour while making e-purchases. Women seem to have a higher proclivity to try out new clothes before buying. The study finds that men contribute 58% to the total online clothing sales, compared to just 36% by women.

This is a trend across the top eight metros and the tier I cities, which contributed 29% and 71% of the value respectively. Kids’ clothing, which has been growing at a scorching pace over the last few years, accounted for just 5% of the apparel sales.

Clothing sales are being driven by India’s young population and the ease in accessing brands. The proliferation of e-commerce in smaller towns and more malls have ensured that digitally connected shoppers are now aware of the latest fashion trends. This has led many fashion brands to offer certain apparel styles online only.

“Every second person on the channel is a new shopper, and it is imperative for brand managers and marketers to get actionable insights into online shoppers,” Nielsen Global Connect president (south Asia) Prasun Basu said.

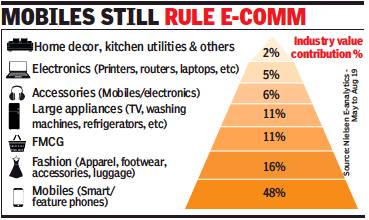

Beyond clothing, footwear and fashion accessories contribute the most to the fashion segment, accounting for 23% and 17% share respectively of the category. Fashion, however, is a distant second in the purchase pyramid chain in the ecommerce universe, where mobile phones rule with a 48% share (see graphic).

The report also shows that maximum online sales (23%) happen between 8 pm and 11pm — when people are back from work, which reinforces the consumer’s quest for convenience with anytime, anywhere access to the e-shopping cart. Nielsen’s data is based on the recent festive sales period, between September and October, and includes 190,000 internet users spread across 52 cities.

The festive season, which saw combined sales of Rs 31,000 crore by Amazon and Flipkart, also showed that consumers prefer to make big-ticket purchases such as mobiles, television and electronic items during that time. This trend is not as pronounced for smaller value items such as clothes and FMCG products.

Online shoppers anticipate and hold back their spending for the sale periods. More than 84% of sales came from this period of ‘Big Day’ sales.

What Indians buy online

Aparna Desikan, June 5, 2019: The Times of India

From: Aparna Desikan, June 6, 2019: The Times of India

E-tailing market is moving away slowly from just selling mobile phones and electronics to grocery and fashion products.

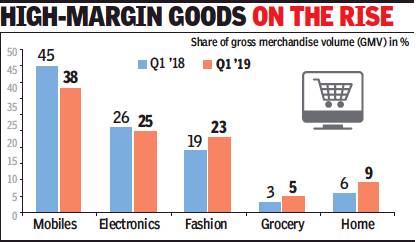

A study by management consulting firm RedSeer said that the share of mobiles and electronics has dropped to 38% in the January-March quarter of 2019 from 45% in the same time last year. It has been steadily dropping since then. During April-June last year it fell to 44%, and to 40% in the following quarter and to 39% in October-December last year.

“Indian e-tailing ecosystem always had a high share of mobile devices category, with the figure often exceeding 50% of all gross merchandise volume (GMV) in certain quarters. The mobile category share started dropping below 40% since 2018 and likely to stay at 35% for 2019 as a whole,” said RedSeer Consulting director Ujjwal Chaudhry.

Mobiles and electronics still take the largest share of the pie, followed by fashion — which hovered around 21-23%. Industry players feel that the change bodes well for the whole ecosystem — for horizontals; it indicates a clear pathway to profitability, with a GMV composed of higher margin non-mobile categories. For verticals, this growing comfort with non-electronics helps them to increase their total consumer base and attract buyers by offering a better experience. RedSeer’s Chaudhry adds that while for customers it means convenience and better options, for e-tailers it margins move on from just sub 10% (with mobiles and electronics) to 30-40% with smaller articles.