Kichak, Kichaka

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

Kichak, Kichaka

The Kichak is one of the wandering predatory tribes met with in various parts of Bengal, characterized by the peculiar physiognomy of the Indo-Chinese races. Their home is properly the Morang, or Nepal Tarai, but gangs of them have settled in the north-eastern districts of Bengal.

It is not admitted in Nepal that the Kichaks and Kirats,2 or Kirantis, are the same, an opinion held by Buchanan,3 but it is beyond a doubt that they are both scions of a pure Turanian stock, and that they live together in Dinajpur, a part of the ancient Matsyadesh, in Sikhim, and in Nepal.

The Kirantis, again, are identified by Col. Dalton4 with the Kharwars of Shahabad, a tribe of undoubted Turanian descent; while B. H. Hodgson5 includes the Kichaks among the broken sub-Himalayan tribes, which he designates Awalia, from their power of withstanding damp or malaria (Sanskrit Ola), along with the Kochh, Garo, Bodo, and Dhimal. They are, moreover, classified with the later Turanian immigrants from the north, and their language is pronounced to be of the complex or

1 Randa, in Bengali, means "childless." Randa, in Sanskrit, means barren.

2 Kirata, literally means one living outside the city, and was applied to different aboriginal tribes dwelling on the east of Bharata. Dr. Daniel Wright, writing from Katmandoo, in April, 1875, says, that in the Morang are two tribes, included under the generic name Kichak, called Kochya and Mechya, who have no claim to be regarded as Kirats. According to the Pandits the genuine Kirats ate the Yakhas and Khombos of the eastern, and south-eastern parts of Nepal.

3 "An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal," p. 7.

4 "Ethnology of Bengal," 128.

5 "Essays," part ii, 14.

pronomenalized type tending, like their physical attributes, towards assimilation with the Dravidian, or the Santal dialect.

The Kichak history is a strange and puzzling one. In the Mahabharata, Kichaka is the brother-in-law of Rajah Virata, ruler of the Matsya country, who was slain by Bhima, the second of the Pandava brothers, for insulting his sister Draupadi. The next tradition, preserved by Buchanan,1 is that the Kichaks were subjects of Bhimsena, who was either a Rajput ruling their country, or a Kichak himself. The inhabitants of Puraniya, early in the present century, had confused accounts of ancient invasions, and conquests of the Kichak tribe, and mentioned several old princes of Morang to whom worship was still paid, and whose usual priests, or "Pariyal," are said to have been descended from Kichak warriors. Furthermore, a legend survives that Prithu, Rajah of Kamrup, fearing that his purity would be denied by the sight of an abominable tribe of "raw-eaters," called Kichak, who were invading his kingdom, instead of leading his troops to battle, threw himself into a reservoir of water, and perished, leaving his capital and country to fall without a struggle into the hands of the barbarians. The causes which have reduced a powerful and aggressive people, as indicated by these tales, into the present abject condition of the Kichak race, are difficult to explain. In habits they resemble the vagrant tribes of Nats Badhaks, and Siyal-Khors, fragments of primitive Indian races, whose genealogy has still to be written; while in features, complexion, and physique they approximate to the Mags and Chakmas of the south-eastern frontier.

The settlement of a gang of Kichaks in the suburbs of Dacca has furnished a favourable opportunity of studying their peculiar customs and habits. In 1843, an extensive robbery was committed at Narayanganj, an important town near Dacca, and all attempts to trace the robbers failed until suspicion fell upon a band of Nats, as they were called, who were then passing through the district. The whole party was apprehended, and the robbery brought home to several individuals belonging to it. Further enquiries revealed the existence of numerous allied bands in various parts of Bengal, and of one in particular, engaged as coolies at an Indigo factory, who supplemented their wages by robbing the villages around. Government directed the punishment of the guilty, and the location of the remainder under surveillance at Dacca, where they obtained employment under the municipality. It is said that about thirty men, besides women and children, were thus provided for, who though in a position most uncongenial to their tastes, have always proved good and useful citizens. Thirty years' contact with alien races, and isolation from their brethren, have produced great changes in their characters and habits, yet the Dacca Kichaks still preserve many early associations and peculiarities.

According to them the Kichak tribe has eight subdivisions, or septs, in the following order of precedencce:�

Latia, Gangla, Suluki, Kaiya, Lathri, Dadar, Numiya, Chaya. Members of the first four families form the hereditary priesthood, who officiate at all religious ceremonies; but should one of their representatives not be at hand, the head of the family, or party, may perform the service. Each subdivision has a Sardar or Rai, who is elected (Khun-bandhna) by m[an]hood suffrage. It is a remarkable fact that no subdivision can enumerate more than eight Sardars. The chiefs of the Sulauki in order are Borak, Kabah, Dewa, Salawat, Moti Ram, Madari, and Babu Ram; of the Lathri, Hona, Kone, Babu Ram, Subha and Bahadar; of the Nuniya, Udasi, Kazania, Gora, Kutb, Ruri, Nafar, Dhun Singh, and Usman. The names of the chiefs, as well as those of the different septs are mainly Hindi, an indication that they were given in comparatively modern times, when the tribe broke up into two divisions, one inhabiting the plains, the other the sub-Himalayan Tarai.

A Panchait, as among Hindus, settles all disputes, and punishes the guilty, while in olden days it passed sentence of death on spies and informers.

Their religious belief is very simple. God as an abstract conception is an incomprehensible idea, but when thunder rolls overhead they say it is the voice of Gokhain (Gosain). Furthermore, they have a fetich in the oval, bright scarlet-coloured seeds of the "Rakta Chandana"1 (Adenanthera pavonina), but it is difficult to ascertain the exact meaning attached to them. It may be that the wondrous colour and rarity of the seeds have excited their astonishment, and suggested in some undefined way the action of a powerful and benevolent spirit, of whose power they are the visible symbol; but the mysterious respect with which they are treated, and the worship that is paid, presupposes the existence of a spirit embodied in their substance,

1 The seeds are in general use as weights by goldsmiths, and are often strung on a thread to form a necklace. The same Sanskrit name is given to the red Sandal wood tree (Pterocarpus Santalinus) of the Coromandel coast.

1 "Eastern India," vol. iii, 39, 406.

or acting and communicating its power through them. Whatever be the true explanation of the selection, each Kichak carries a few wrapped in his waist cloth, and, whenever a marauding expedition is starting, each man arranges the seeds on the ground before him, saturates them with sweet oil, makes obeisance, and prays for success in the coming journey. The spirit that watches over them is called "Akha," but they also believe in the existence of domestic or household gods, symbolized by small brass idols, called "Devi Durago," and corresponding to the Gramdevatas of the modern Bengali villages.

On critical occasions the chiefs sacrifice a goat to "Akha," but this is neither an usual nor obligatory act.

Kichaks bury their dead, placing in the hands of the corpse a few copper coins, and depositing in the grave, water, sweetmeats, rice, and spirits. Their ideas of a future state are confused and rudimentary, and when asked to give a reason for placing perishable articles in the grave, they either reply that their fathers did so, or that it is good for the deceased person to have them.

Kichaks eat the flesh of almost all animals, but never touch beef. They are very partial to the flesh of the Iguana (Goh-samp), jackal, pig, and civet cat (Viverra), but the flesh of snakes is abhorred. Intoxication is universal, and every domestic occurrence is commemorated by a feast, at which an unlimited quantity of coarse fiery spirits is consumed. Polygamy is practised, but three wives are considered enough for the greatest chief. Divorce is common and fashionable, and the marriage bond is easily unloosed, although it has been tied in the presence of the assembled tribe. Social prejudices are unknown, and they have no scruples in eating with Hindus, Muhammadans, or Christians. Omens derived from the appearance, cries, or movements of animals are, as with the Thugs, universally relied on as having a perceptible bearing on the issue of voluntary acts. If a jackal calls in front, or on the right hand, of a gang starting on an expedition, the departure is postponed, but if it howls in the rear, or on the left hand, the augury is favourable, and the start is at once made.1 This strange belief in the prescience of the jackal has gained for the Kichaks another appellation, that of Lohari Khanu.

In former days the tribe was armed with iron weapons, but as these led to identification, they have been laid aside, and bamboo spears and swords are made as required, and thrown away as soon as the work of the party is completed.

About thirty years ago1 the chief Sardars held Mustajiri, or farmed land, and it was alleged that the Sardars, along with the Mundle, village officials, and even the police participated in the plunder brought home by the gangs. Before an expedition started, the Panchait met and fixed its strength, the individuals who were to compose it, and the rates at which the booty was to be allotted. The Sardar got a double portion, while men, women and children shared equally. The widows and children of any man killed, or who died, either received a large donation or a pension, so long as the widow remained unmarried. Finally, goats were sacrificed, fidelity pledged, and, after dipping the fingers in the blood of the victims, the flesh was eaten, and spirits drunk.

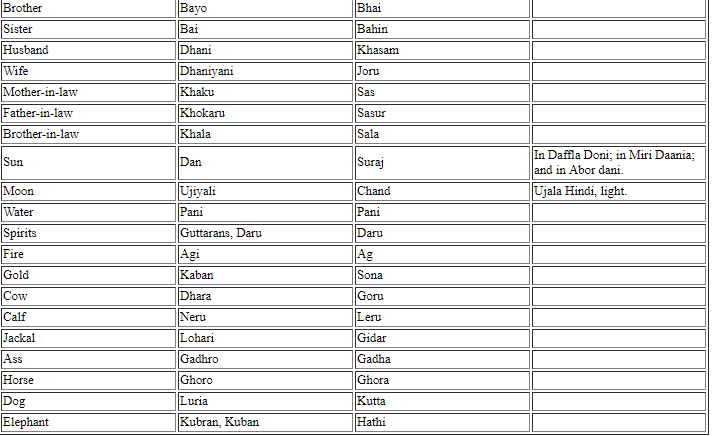

The Kichak language is mainly Hindustani, with words derived from hill tribes residing along the northern frontiers of Bengal. In the following vocabulary sixty per cent of the words are either pure, or broken, Hindustani, while a few of the remainder are traced to races living in proximity to the Kichaks.

1 "Asiatic Journal," 3rd series, vol. i, 466; iii, 192.

1 The manifestation of an omen is interpreted in a variety of ways by different tribes. Among the Thugs an omen on the right hand was portentous, on the left auspicious at the beginning, but the reverse at the end of an expedition; while a pair of jackals moving in either direction in front was ominous.