Milk, dairy products: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Adulteration

2011

The Times of India, March 17, 2016

68% of milk adulterated, new kit to test in 40 seconds

With over 68% of the milk in India found adulterated in a 2011 Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) study , the government is working towards providing an accurate, portable test kit for the important staple. Science and technology minister Harsh Vardhan told the Lok Sabha that a new scanner had been developed which can detect adulteration in milk in 40 seconds, and pinpoint the adult rant.

Earlier, for every type of adulteration, a separate chemical test was required.Now a single scanner can do the job, he added. The scanner is priced at about Rs 10,000, and each test would cost a mere 5 to 10 paisa.

Most common adulterants found in milk are detergent, caustic soda, glucose, white paint and refined oil, a practice considered “very hazardous“ and which can cause serious ailments. Vardhan said in the near future, even GPS-based technology could be used to track the exact location in the supply chain where the milk was tampered with.

National Milk Safety and Quality Survey, 2018: 50% samples failed

Sushmi Dey , 50% of samples in milk test fail quality norms, November 14, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sushmi Dey , 50% of samples in milk test fail quality norms, November 14, 2018: The Times of India

Nearly half the milk samples tested by the food safety regulator, which includes raw milk and processed milk, have been found to be non-compliant in terms of the required standards. Of this, around 10% samples were found to be unsafe raising concerns over the need for better regulation and testing of milk consumed in the country.

Tests found 39% of total samples to be non-compliant but safe. But the regulator expressed particular concern about processed milk where 46.8% samples did not meet standards set by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), of which a significant 17.3% share was found to be unsafe.

On the contrary, only 4.9% of raw milk samples were found having safety issues. The rest 45.4% of raw milk was found to be non-compliant with regulatory standards but safe for public health, according to the findings of the National Milk Safety and Quality Survey, 2018.

“We are surprised and particularly concerned that processed milk which is mostly from the organised sector is non-compliant and have a higher percentage of safety issues as compared to raw milk samples. We have the details of these processed milk samples, including their brands and locations. We are doing a detailed investigation and will soon take action to resolve this,” FSSAI chief executive Pawan Agarwal said.

Agarwal maintained milk in India is “largely safe” though there are quality issues, which are being looked at by the regulator. The unsafe contaminants are coming mainly from “poor farm practices”, he said.

Findings of the survey show main contaminants causing safety concerns are related to presence of antibiotics, soil fertilisers like ammonium sulphate and toxins like Aflatoxin M1- found on agricultural crops such as maize, cottonseed and tree nuts — above tolerance level.

Milk cheats should get life term: SC

The Times of India, Aug 06 2016

AmitAnand Choudhary

Expressing concern over the alarming level of milk adulteration in the country , the Supreme Court on Friday favoured stringent punishment of life imprisonment for the offence which, at present, is punishable by only up to six months in jail or fine. A bench of Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justices R Banumathi and U U Lalit said there was an urgent need to tackle the menace of growing sale of adulterated and synthetic milk. It said milk adulteration could adversely affect the growth of future generations as it was the staple diet of children and infants.

Asking the Centre and states to consider amending the present lenient law, the bench said Uttar Pradesh, Bengal and Odisha had already amended the law making adulteration punishable by up to life imprisonment and there was not hing wrong in following their footsteps for a stringent law.

“It will be in order, if the Centre considers making suitable amendments in the pe nal provisions on a par with the provisions contained in the state amendments to the IPC. It is also desirable that the Centre revisits the Food Safety and Standards Act to revise the punishment for adulteration making it more deterrent in cases where the adulterant can have an adverse impact on health,“ it said.

The SC directed the government to spread awareness about the hazardous impact of milk adulteration and methods for detection of common adulterants in food. It directed the Centre and states to evolve a complaint mechanism for checking corruption and other unethical practices.

“Adulteration of milk and its products is a concern and stringent measures need to be taken to combat it,“ the bench said and referred to a 2011 re port of Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) which said that over 68% of milk sold in the market was found to be adulterated.

The report said cases of milk adulteration were rampant, with all samples in Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bengal, Mizoram, Jharkhand and Daman & Diu found to have been adulterated.

The court passed the order on a bunch of petitions filed by people from different states seeking its direction to governments to provide for stringent punishment for milk adulteration. Advocate Anurag Tomar, appearing for the petitioners, contended that milk contaminated with synthetic material was being sold in various states, posing serious threat to the life and health of consumers.

Consumption, Production

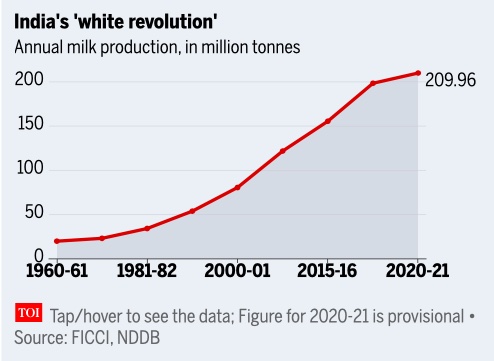

1960-2021

Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury & Rajesh Sharma, April 28, 2022: The Times of India

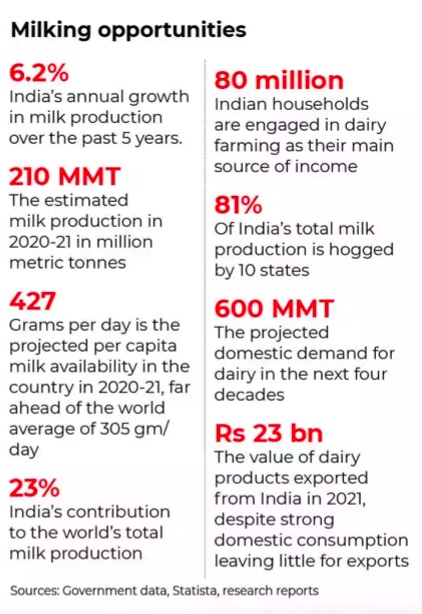

Operation Flood — the success story that made India go from seeing acute milk shortages in the 1960s to becoming the world’s largest producer of milk. That’s a title India has held on to for two decades now, and the total output continues to zoom up.

Milk production in the country increased by nearly 64% in the past decade and the provisional figures for 2021-22 are within a kissing distance of 210 million tonnes. That’s an uptick of 5.8% year-on-year at a time when the global milk output only grew by 2%. So when PM Narendra Modi gloats that “India produces milk worth Rs 8.5 lakh crore annually”, higher than the turnover for wheat and rice, he has hard data backing him up.

Unfortunately, hidden behind these stellar numbers is a story of chronic inefficiencies and wasted opportunities. Simply put, despite boasting the world’s largest cow and buffalo population — numbering over 302 million in the last livestock census of 2019 — India does not know how to milk the full potential of its milch herd. To date, none of the major Indian dairy companies feature on the list of the world’s top 15 major dairy giants, and only one — Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) that markets dairy products under the Amul brand — makes it to a top-20 list.

According to the Integrated Sample Survey, while the average productivity of cattle jumped up 27.95% between 2013-14 and 2019-20 — the highest increase in productivity in the world — the average yield per animal in India is 1.5 times lower than the global average. In 2019-20, the average annual productivity of Indian cattle stood at 1,777 kg per animal as against the world average of 2,699 kg per animal.

The difference is even more stark when India’s yield is measured against the other leading milk-producing nations. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), between 2017 and 2019, the average yield per in-milk animal in the US was eight times higher than that in India.

Even New Zealand, with a much smaller cattle population, managed a three times higher average yield per animal and is the world’s largest milk exporter.

So what ails the dairy industry?

High dependence on unorganised sector

In the developed countries, about 90% surplus milk is handled through the organised sector. But India is different. About 54% of milk produced is marketable surplus and remaining 46% is retained in villages for local consumption.

"Out of the marketable surplus available with farmers only 36% is handled by organised sectors evenly shared by cooperative and private sector,” says a 2020 report by India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), a trust established by the department of commerce.

However, it is the organised sector that has regularly posted faster growth in terms of milk output while the unorganised sector is marred by lack of access to technology, unhygienic practices and unsteady market linkages.

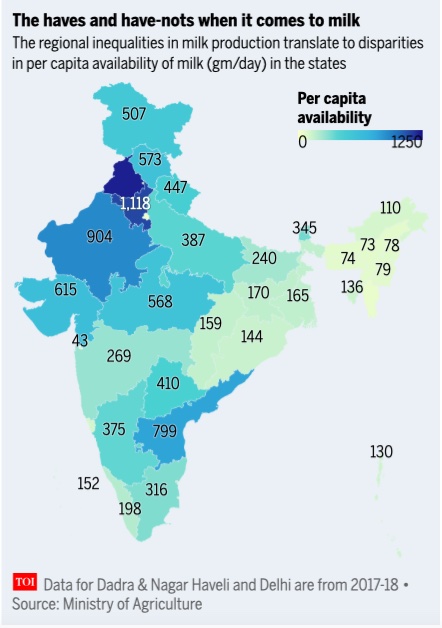

Skewed state-wise milk production

The five top milk-producing states in the country account for over half of the total national milk output. With a 16% share in India's total production, Uttar Pradesh continues to be the largest milk-producing state, followed by Rajasthan (12.8%), Madhya Pradesh (8.62%), Gujarat (7.7%) and Andhra Pradesh (7.6%). The top-10 milk-producing states account for a whopping 81.5% of the country’s output.

And the number of milch animals in a state has no bearing on its milk production. According to government data, Assam boasted a larger adult female bovine population in 2019 — numbering 3.95 million — than Haryana (around 3 million). Yet the latter is the eighth-largest milk producer in the country, while Assam ranks among the 10 worst-performing states.

These regional disparities in milk production — stemming from factors ranging from the availability of quality feed and fodder to the genetic potential of the bovine population and scope for breed improvement — need to be addressed if India is to up the ante for the dairy industry.

The skewed milk-production map of the country underscores the need for adequate distribution channels between states. But in the absence of adequate infrastructure, including cold-storage facilities, wastages dog the dairy industry. According to research conducted by Assocham, an industry pressure group, about 3% of the milk produced gets wasted annually.

Small herds, higher costs

The dairy sector in India is also disadvantaged by small herd sizes. With 95% of players in the business having herd sizes of just one to five animals, these milk producers remain mired at subsistence levels. They are unable to capitalise on economies of scale that come in with the larger dairy farms.

The small-scale ownership pattern is linked to challenges in providing specialised or intensive management to improve milk yields, unless they become a part of a dairy cooperative. Moreover, volatility in milk demand and prices discourages farmers from growing their herd size as they don’t want to take on the additional risks.

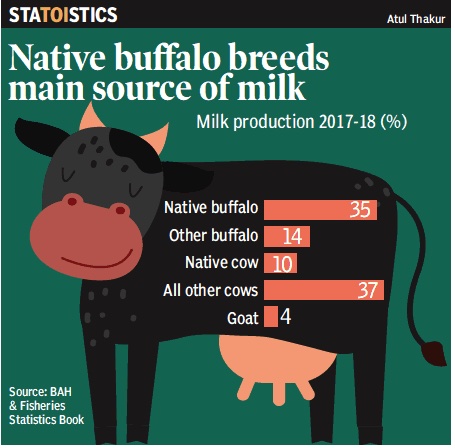

Milk yield and cost of production also depend on the type of bovine owned — 49% of India’s milk production comes from water buffaloes while crossbred cows have become increasingly popular because of their high average-yield rates.

A 2016 research paper established that the average per litre cost of milk production for crossbred cows stood at Rs 20.80. On the other hand, the average price for buffalo milk worked out to Rs 32.43.

However, the overall net return per litre of milk from crossbred cows was found to be Rs 5.20 while that for buffaloes was much lower at Rs 3.67. In both cases, the farmers with small-herd sizes benefited the least.

Feed and fodder shortages

Livestock producers meet their fodder needs through a combination of crop residues, grazing lands — be it fallow and harvested agricultural lands or forests — and cultivated forage crops. But while grazing lands are gradually disappearing due to encroachments for agricultural and non-agricultural uses, the availability of fodder and feed are seeing serious shortages.

The department of animal husbandry in a 2019 advisory to states had acknowledged that “the area under fodder cultivation is limited to about 4% of the cropping area, and it has remained static for the last four decades”, while the bovine population is multiplying. Industry body Ficci estimated the deficit of dry fodder, concentrates and green fodder — any type of feed that is made from green crops like legumes, cereal crops or grass and tree-based crops — at 10%, 33% and 35%, respectively, in 2020. Stakeholders and experts fear that by 2025 this gap will widen further.

“Limited fodder production area restricts compound cattle feed use to 8-10 MMT [million metric tonnes], while the actual total dairy feed requirement is 80 MMT,” estimates United States Department of Agriculture. By 2050, India’s demand for forage is anticipated to grow by 24% and without access to good-quality green forage the growth in the dairy sector will become unsustainable.

Consumption gaining steam

India today is not only the biggest milk producer, but it has also become the largest consumer of milk and this is one of the key reasons for India’s low exports of dairy and associated products.

Based on estimates of population growth and increase in urbanisation for the next four decades, it is anticipated that India will need around 600 million tonnes of milk per year to fulfil domestic demand. This means that India’s milk production needs to grow at around 3.2% CAGR for the next 40 years.

That can’t happen if the dairy sector does not address all the above inefficiencies. And if the domestic herds can’t deliver, the country may have to make a U-turn and start importing milk and dairy products. That, ironically, is something dairy cooperatives and stakeholders have long fought against.

2010-18

January 28, 2019: The Times of India

From: January 28, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Milk production on India, 2010-18

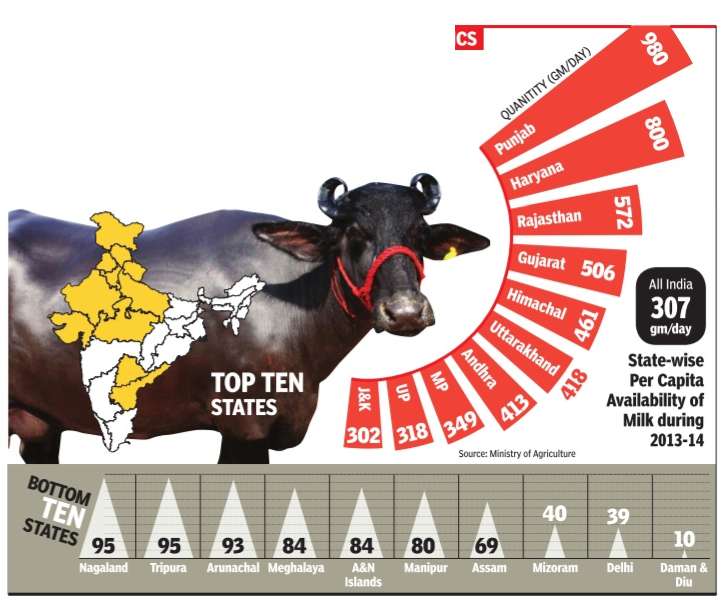

2013-2014

NOT QUITE A FLOOD

The Times of India Mar 06 2015

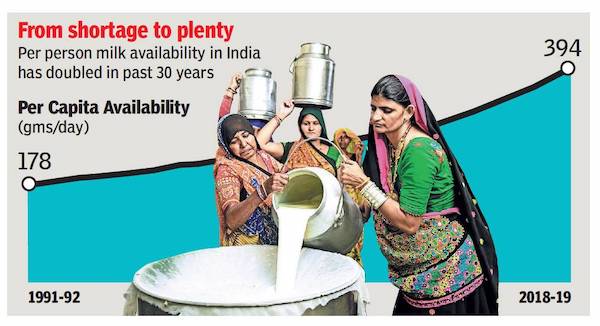

In India, 70% of cattle are reared by small and marginal farmers. Official data shows that the average productivity of milch cattle in India was 1,385 kg per year, much lower than the world average of 2,319 kg per year. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization categorizes consumption of more than 411 gm of milk per day as high, 82-411 gmper day as medium and less than 82 gm as low. In 2013-14, the per capita availability of milk in seven Indian states was more than FAO's high consumption mark while 5 states and UTs were in the low consumption category.

2015 and 1970-2015 respectively

March 28, 2018: The Times of India

Milk production, 1970-2015

Milk Consumption in India’s top 10 states (The years are not clear but presumably the grey bars could refer to 1980 and the blue bars to 2015)

From: March 28, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

India, China, Pakistan and the world

Milk production, 1970-2015

Milk Consumption in India’s top 10 states (The years are not clear but presumably the grey bars could refer to 1980 and the blue bars to 2015)

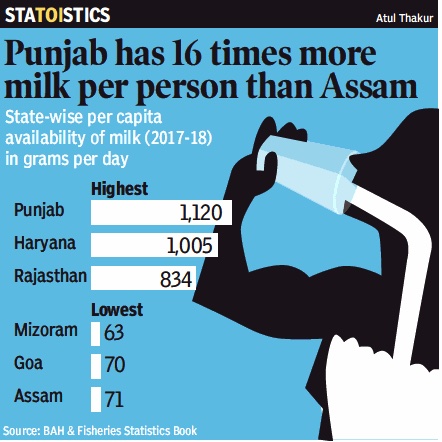

2017-18, state-wise consumption

From: March 10, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

State-wise per capita availability of milk (2017-18) in grams per day

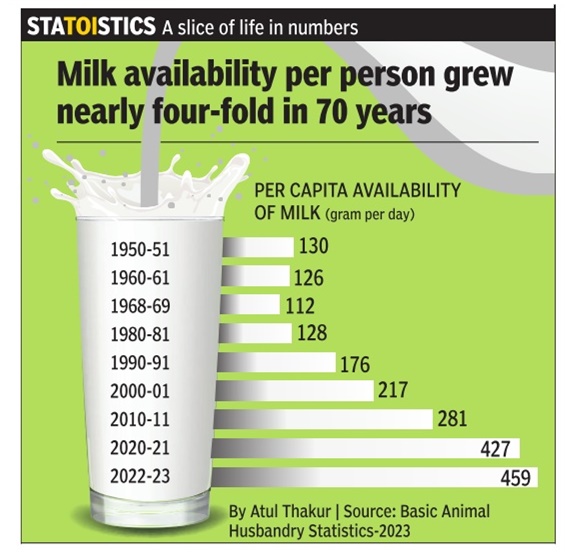

1950-2023

From: June 29, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Per capita limitability of milk in India, 1950-2023

2021

Himanshu Kaushik & Prashant Rupera, May 26, 2023: The Times of India

AHMEDABAD/VADODARA: Gujarat has earned the title of the milk capital of the country for the strides it has made in the organized dairy sector, but neighbouring Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh have outpaced Gujarat in terms of the value of milk output over the past decade.

A report compiled by the Union ministry of statistics and programme implementation (MoSPI) which compares the value of milk output of all states over the past decade (2011-12 to 2020-21) says that while the value of milk output in Gujarat rose by 54.8% in the last decade, Rajasthan registered an increase of 129.6% and MP a 120.6% rise.

The report states that Gujarat maintained its fourth position in the country in terms of milk output value. According to the report, Rajasthan ranks first, followed by UP, Maharashtra, Gujarat and MP. The report has used constant prices to compare milk output value.

Gujarat never enjoyed the status of being India's largest milk producing state, but when it comes to the share of the organized dairy sector and that of dairy co-operatives, Gujarat enjoys the biggest share in the country.

"Gujarat has always been one of the top five milk producing states in the country and enjoys the largest share as far as the organized co-operative sector is concerned. The value of milk output in the decade between 2011 and 2021 is proportional to the growth in the quantity of the milk produced," said Jayen Mehta, managing director of the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), which markets the country's largest milk brand, Amul.

A proportional increase is observed in milk production and milk output value in all the top five milk producing states of the country.

GCMMF and 18 district milk unions of Gujarat, who are member unions of the federation, currently procure about 275 lakh kilograms of milk per day (LKPD), the highest amount procured by any state-level federation in the country. Interestingly, milk production in Gujarat has grown by 70% between 2011 and 2021. From 268.96 LKPD in 2011, the state was producing 458.14 LKPD in 2021, a 70 % increase in milk production.

In Rajasthan, milk production was 370.19 LKPD in 2011, and rose to 911.36 LKPD in 2021, a 146 % growth in milk production and unsurprisingly the value of its milk output grew by 129.61%. Similarly, in MP, milk production stood at 223.26 LKPD in 2011 and rose to 520.66 LKPD in 2021, a 133% increase in production.

In Maharashtra, milk production was 232.03 LKPD in 2011 and rose to 391.9 LKPD in 2021, a 69% increase. Uttar Pradesh, which enjoys the status of India's largest milk producer, saw milk production increase by 46% from 2011 to 2021. Against 617.97 LKPD produced in 2011, UP produced 904.25 LKPD in 2021.

‘Control’ of Milk Products

1960s-‘70s

Abhilash Gaur, Oct 31, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Oct 31, 2021: The Times of India

In the 1970s, Uttar Pradesh had a law that gave a police officer the power to “enter and search any place or premises”. It wasn’t about curbing gun-running, or bootlegging, or prostitution. The ‘UP Milk and Milk Products Control Order’ was all about preventing the diversion of milk to other states, and for other uses, such as the production of paneer and mithai in the summer months.

Nor was UP alone in this. In August 1965, West Bengal had banned the manufacture of dairy sweets in Kolkata through the West Bengal Channa Sweets Control Order. Punjab’s milk products control order had come into force in June 1966. The Centre had issued ‘Delhi, Meerut and Bulandshahr Milk and Milk Products Control Order’ in 1969. And in Delhi, wedding hosts weren’t allowed to serve sweets made of “khoya, chhana, rabri and khurchan to more than 25 persons at a time at social functions,” following an order passed in 1965.

All of these orders were meant to fight the severe shortage of milk in the summer months when fodder and water for milch animals were scarce. Even otherwise, India was a milkstarved country in the first few decades after Independence. During 1952-55, hardly half a cup of milk (126g) was available per person, per day. In some states, the average daily availability was just 30-50 grams per person. A large part of the country’s milk requirement was fulfilled with imported – often donated – milk powder. On March 29, 1967, this discussion occurred in the Rajya Sabha: Niren Ghosh, MP from West Bengal: “There is dearth of milk powder supply in West Bengal. As a result, the entire milk supply scheme is going to collapse next month, and the children and the mothers are not going to get milk.”

S Chandrasekhar, minister of health and family planning: “I know, sir…all the available supplies are being directed to Bihar because of the drought situation…even in Bihar, since the supplies are limited, they are being directed for the use of vulnerable groups of population like nursing mothers and infants and young children.”

So, the policymakers of that era had a reason to ban the diversion of milk for all “non-essential” uses, including mithai. “Government are aware that manufacturers of milk sweets will be adversely affected. But milk sweets are a luxury product,” minister of state for agriculture Annasaheb Shinde said in May 1969.

Happily, Operation Flood was successful, and at the start of the 1990s you find minister of state for agriculture K C Lenka telling Lok Sabha: “now the ban is on conversion of milk into milk powder and condensed milk only.” Three more decades have passed, and few remember those summers of milk shortage. Now, if a cop knocks at your door, you know he won’t say, “Got milk?”.

Dairy farming: The state-wise position

Maharashtra, 2018

Across Maharashtra’s once prosperous milk belt, many dairy farmers face this stinging reality: the milk they sell is cheaper than water.

Some get Rs 23 per litre of cow’s milk, mainly in the milk hub of Kolhapur. But most earn just Rs 17-19. By comparison, bottled water sells at Rs 20 a litre. Once the milk reaches consumers in cities, the price doubles to Rs 40-44. But farmers do not get a share of the mark-up.

As the milk economy curdles, the sight of milk dumped on roads has become emblematic of farmer protests. A year ago they got up to Rs 27 per litre of cow’s milk, but prices plunged by Rs 4-10 eight months ago as a result of a surplus and a crash in international skimmed milk powder prices.

With several dairies announcing cuts in procurement rates by Rs 2 from Thursday and some choosing not to buy cow’s milk at all, the crisis is mounting.

Babasaheb Mane from Sangli’s Mahuli village was once a proud dairy farmer. He made Rs 30,000 a month from his four cows last year. Today, he and his wife work as farm labourers to keep their home running.

Mane sells 40 litres of milk daily for Rs 17 per litre.

Since Nov, Maha has milk surplus of 22L ltr per day

I make Rs 720 a day but spend Rs1,000 on the cows. I used to make a profit of Rs 15,000 per month, but now I make a loss of Rs 9,000,” he says. Farmers are trapped between the fall in procurement rates and sharp increase in costs of inputs, including fodder, oil-cakes and lactation pellets for cattle over the last year.

Maharashtra’s formal sector collects 115 lakh litres of milk daily. In June 2017, after the historic farmer strike, the state hiked the procurement price from Rs 24 to Rs 27 per litre. However, prices plummeted in just a few months. Since November, the state has had a surplus of 22 lakh litres per day. At the same time, international skimmed milk powder prices fell 30-40%. Unable to sell their milk powder stock, dairies faced losses and cut the price offered to farmers. Maharashtra currently has stocks of 29,000 tonnes of skimmed milk powder.

The bulk of the state’s dairy sector is private. Only 1% of the state’s milk is bought by the government and 39% by cooperative dairies mainly controlled by the Congress and NCP. As much as 60% is bought by private dairies.

The state admits it cannot control prices in a de-controlled sector dominated by private players. “When the Milk Control Order was in force till mid-2000, the state controlled licences to dairies. But now milk is an open commodity,” said state dairy development commissioner Rajeev Jadhav.

The government has tried to enforce the procurement price of Rs 27 by issuing directives to cooperative dairies. “But the cooperative dairies went to court and in most cases, the high court issued a stay,” said Jadhav. Cooperative dairies accuse the BJP government of trying to crush a sector controlled by the opposition.

Dairies are demanding an export incentive for skimmed milk powder and subsidies to milk farmers, like that offered by Karnataka. CM Devendra Fadnavis has asked the Centre to declare a minimum support price for milk and 10% export incentive on skimmed milk powder.

Those leading the milk agitation say dairies are also exploiting farmers to make a difficult situation worse. “If the entire dairy industry is impacted by skimmed milk powder stocks, how are other states offering higher procurement rates? And why are dairies in Kolhapur able to offer higher rates than other parts of the state?” asks Ajit Navale of the Kisan Sabha. By now, even the bigger dairy farmers are exiting the trade.

In June 2017, after the historic farmer strike, the state hiked the procurement price of milk from Rs 24 to Rs 27 per litre. However, prices plummeted in just a few months

Dairy products: exports

2020, till Dec

Rohan Dua, December 20, 2020: The Times of India

India exports Rs 550 crore dairy items during Covid-19, Ghee tops list

NEW DELHI: During the Covid-19 pandemic, with all its constraints, India has managed to export dairy products worth Rs 554 crore to more than 110 countries so far.

A report by the Agricultural & Processed Food Exports Development Authority (APEDA), the apex body for trade promotion, prepared last week found that the UAE remains the biggest market for Indian dairy products. This year, so far, orders worth Rs 154 crore were placed by the UAE alone.

The US came next (Rs 110 crore), followed by Bhutan (Rs 78 crore), Singapore (Rs 53 crore), Saudi Arabia (Rs 39 crore) and Australia (Rs 37 crore).

Last financial year, India had exported dairy products worth Rs 1,341 crore, significantly lower than the Rs 2,423 crore the year before that.

So, while this year’s figures have been less than half so far, the pandemic effect and the fact that there still are four months to go have been seen as positive indicators.

Milk production from Uttar Pradesh (30 MT), Rajasthan (23 MT), Andhra Pradesh (15 MT) and Gujarat (14 MT) have largely contributed to these exports.

Over four years, India’s dairy exports have overall touched Rs 5,500 crore trade.

The top export in that period has been ghee (Rs 1,521 crore).

The UAE has imported ghee worth Rs 74 crore this year so far.

“One of the reasons ghee is so popular is the presence of the Indian expat community in the Middle East,” Union minister of state for animal husbandry and dairy Sanjeev Balyan told TOI.

Butter has also been a big export over the past four years (Rs 1,486 crore), followed by farm cheese (Rs 435 crore) and milk cream (Rs 230 crore). There’s also been a small market for buttermilk (Rs 20 crore). Whole milk carton export has been worth just Rs 0.5 lakh.

“As far as the low export and trade of packed milk food supplements and powdered milk is concerned, India has a lot of catching up to do. Other countries already have big international players which make cheaper products for the retail market,” Balyan said.

The report was submitted by APEDA to the animal husbandry department last week.

Sources of milk, animal-wise

2017-18

From: March 3, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Sources of milk, animal-wise, 2017-18

2022-23

From: June 21, 2024: The Times of India

See graphic:

Species – wise share in milk production in 2022-23

Varieties

A2 indigenous cows popular/ 2017

Namita Devidayal, Desi doodh is new health fad, April 23, 2017: The Times of India

The best reason to save the desi cow has not hing to do with bovine politics. It is milk. Desi doodh, or A2 milk from indigenous cows, is becoming the latest health fad, with small dairies and big brands like Amul entering the market.

Much of the cow milk available in the market is A1, from crossbred or foreign cows.Though research is not conclusive, some studies have shown that A1 can trigger inflammation in the body, potentially leading to ailments like diabetes and heart disease. A2, on the other hand, has found favour with the health-conscious and the lactose-intolerant who say it is easy to digest.

In fact, it's already got takers abroad. A Sydney-based company , a2 Milk Company , has found an international following in New Zealand and China and is expanding to the United States. Back home, Amul has responded to the new interest in A2. It recently launched a premium desi cow milk product in Ahmedabad and plans to add the Surat market next. However, Amul manag ing director R S Sodhi admits that the market is niche. “When you want to sell it at a premium price, the market is very small. But gradually , awareness is growing.“

A small but growing band of dairy farmers is also catering to this new market. V Shivakumar, a former Wall Street programmer, realized the difficulties of sourcing A2 milk because of a lactose-intolerant newborn. He went on to form the Coimbatore-based Kongu Goshala to preserve Tamil Nadu's Kangeyam and Tiruchengodu breeds. He also runs a mobile app Kongu Maddu, where people can place orders for A2 milk. Gurgaonbased Back2basics breeds Gir cows for A2 milk which it supplies to households in Delhi, Noida and Gurgaon.

When retired market researcher Titoo Ahluwalia first started keeping cows at his farm in Nandgaon, a coastal village near Mumbai, he was more interested in generating dung for his organic vegetables and ensuring his children grew up around “these gentle, giving animals“. When he read up on desi cows, he realised the benefits of the milk. “Regrettably, many desi varieties of cow are already close to extinction,“ says Ahluwalia.

While most dairy owners deny any problems related to consumption of A1 milk, they do admit that local cows are much more in tune with India's climate conditions, and therefore remain healthier.“Desi cows are heat-tolerant and tick-tolerant, and they have good immune systems, so we hope to have more of our European cows cross-breed with them,“ says Aniket Thorat of Bhagyalaxmi Farms in Pune which prides itself on keeping its Holstein-Freisian cows in a controlled space of wellness -that includes playing Indian and western classical music to them and following organic processes.

Foreign and crossbred cows, such as Holsteins, give far higher volumes of milk compared with, say , the desi Gir cow -the biggest reason for their overwhelming popularity among dairy farmers.Desi cows are bred largely by religious communities and ashrams, where the animal is revered and productivity is not the prime motivation. According to one farmer, there are just about 15,000-18,000 Gir cows left in the country .Brazil, which imported them from India in the late sixties, has a far higher population.

The National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Karnal, has been trying to motivate farmers to shift to A2 breeds, with some success, says Monica Sodhi, a scientist at the institute.“Here, in Karnal, farmers sell A1 milk at Rs 40-45litre, but A2 gets them a higher rate of Rs 65-70litre. Right now, farmers and dairies from all over India have sent us close to 1,000 semen samples to test (genetically) whether they are A2 or A1.“

In 2012, Dr Sodhi published a paper in the Indian Journal of Endocrinology which says that incidence of type-1 diabetes and cardio-vascular diseases is low in populations with high consumption of the A2 variant of milk. “It's closest to mother's milk and is easily digested by humans. However, there's no conclusive study available yet on A1 milk and if it's harmful for health. But what we have seen is that a byproduct created during breakdown of A1 milk in our digestive tract can lead to health problems.“ A combination of health, spiritual leanings, and that eternal quest for the good old days has motivated some individuals to create awareness about the desi cow and to lobby with various agencies to increase its population before it is too late. “Life has reached a point where we really have to rethink what we feed our children every day ,“ says Mumbaibased Rekha Khanna who is working with several gaushalas across the country to promote desi cow products.

Cancer survivor Amit Vaidya, 38, says he returned to India from the US after doctors there told him that he didn't have long to live. Left with no other option, he underwent `cow therapy' and swears by A2 milk and its byproducts, ghee and yoghurt. “For me, though, I have to go one step beyond just having A2 milk; I need to know what the cows are eating -if they are grass-fed, living an organic life. Their milk will also then add nourishment to our bodies. To put it simply , you have to know where and from whom your milk is coming!“ (Additional reporting by Shobita Dhar)

See also

Milk, dairy products: India