USA- India relations: agriculture

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The 1950s and 1960s

Harish Damodaran, June 13, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Harish Damodaran, June 13, 2023: The Indian Express

The Soviet Union’s role in independent India’s early industrialization through supply of capital equipment and technology is well-known. The Bhilai and Bokaro steel plants, Barauni and Koyali refineries, Bharat Heavy Electricals, Heavy Engineering Corporation, Mining & Allied Machinery Corporation, Neyveli Thermal Power Station, Indian Drugs & Pharmaceuticals, and oil prospecting and drilling at Ankleshwar were all products of collaboration with the Soviet Bloc.

Not as widely known is the part that the United States, and the likes of Rockefeller and Ford Foundation, played in India’s agricultural development during the 1950s and 1960s. A brief history of this involvement – through the establishment of agricultural universities and the Green Revolution – is useful in the context of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s upcoming visit to the US for strengthening the “global strategic partnership” between the two countries.

The first Agricultural University

In 1950, Major H.S. Sandhu, who led the reclamation of Uttar Pradesh’s Tarai region, and the state’s Chief Secretary A.N. Jha visited the US and saw the so-called land-grant universities there. These institutions, set up on public land, engaged in agricultural education as well as research and extension activity. This was unlike the agricultural and veterinary colleges in India that merely taught and produced graduates. Research and extension (training farmers in adopting scientific cultivation practices) was largely left to the state agricultural departments. On their return, the two officials recommended to the Chief Minister Govind Ballabh Pant that a US land-grant model agricultural university – which integrated teaching, research and extension – be established in the densely-forested Tarai area near the Himalayan foothills, being reclaimed and converted for farming. Such a university would provide an environment more conducive for learning, purposeful and problem-solving research, and knowledge dissemination to farmers.

While Pant accepted the idea, the formal proposal to the Centre, for starting an agricultural university at Rudrapur in the Tarai, was submitted only around September 1956. It was based on a ‘Blueprint for a Rural University in India’ prepared by H.W. Hannah, Associate Dean of the University of Illinois. The state government made available 14,255 acres of land and, in December 1958, passed the UP Agricultural University Act. The UP Agricultural University (later renamed as G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology) was inaugurated by the Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on November 17, 1960.

Relationships with US land-grant universities

Hannah’s blueprint was published by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and circulated to interested state governments. It led to as many as eight agricultural universities coming up within eight years, mostly at the initiative of the chief ministers themselves. Punjab, for instance, had Partap Singh Kairon. He, like Pant, was responsive to the needs of farmers: They, and also those of the Tarai, were predominantly refugees from West Punjab’s canal colonies who knew the benefits the Lyallpur Agricultural College had brought to the lands, now in Pakistan.

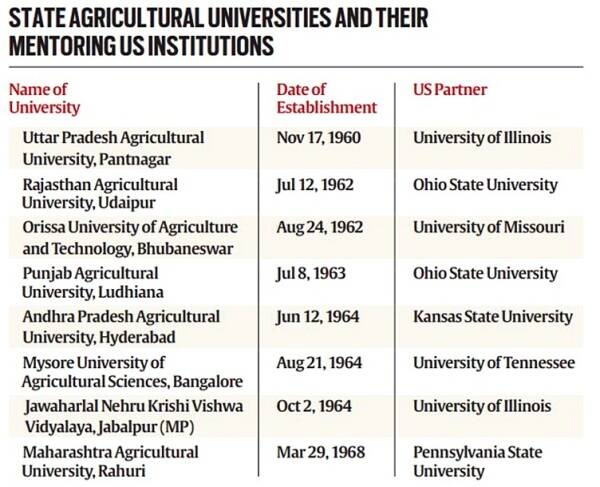

All the eight universities received the US Agency for International Development’s assistance for training of faculty and provision of equipment and books. Each was further linked to a US land-grant institution (table), whose specialists were involved in curriculum design and putting in place research and extension systems in the new universities. Many even stayed in the university campuses for extended periods.

The universities were to have their own research farms, regional stations and sub-stations, and seed production facilities (G.B. Pant University, from 1969, also began marketing its seeds under the ‘Pantnagar’ brand). The importance the US accorded to the whole project can be gauged from its ambassadors John K. Galbraith and Chester Bowles gracing the opening of the Orissa and Mysore agricultural universities respectively.

The Green Revolution’s seeds

Traditional wheat and rice varieties were tall and slender. They grew vertically on application of fertilizers and water, while “lodging” (bending over or even falling) when their ear-heads were heavy with well-filled grains. The Green Revolution entailed breeding semi-dwarf varieties with strong stems that didn’t lodge. These could “tolerate” high fertilizer application. The more the inputs (nutrients and water), the more the output (grain) produced.

In 1949, an American biologist S.C. Salmon stationed in Japan – under US occupation after World War II – identified a wheat variety developed at an experimental station there. Called ‘Norin-10’, its plants grew to only 2-2.5 feet, as against the 4.5-5 feet height of traditional tall varieties. Salmon took Norin-10’s seeds and gave them to Orville Vogel, a wheat breeder at the Washington State University, Pullman.

Vogel crossed Norin-10 with locally-grown US winter wheats. From those crosses, one variety giving 25% higher grain yields was selected in 1956 and released as ‘Gaines’. Vogel also shared the seeds of Norin-10 and his original crosses with Norman Borlaug, working with the Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico. Borlaug, in turn, crossed these with the spring wheats grown in Mexico. By 1960-61, many varieties incorporating the Norin-10 dwarfing genes in a spring wheat background were released.

How those seeds came to India

Around 1957-58, M.S. Swaminathan, then a barely 33-year-old scientist at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in New Delhi, saw a paper on the Norin-10 genes by Vogel in the American Agronomy Journal. He wrote to Vogel for the seeds of ‘Gaines’. Vogel responded, but noted that ‘Gaines’, being a winter wheat, wouldn’t flower in Indian conditions. He directed him to Borlaug, whose spring wheats containing the dwarfing genes were better suited for the country.

Swaminathan got in touch with Borlaug, who came to India only in March 1963, following a request placed to the Rockefeller Foundation. He sent the seeds of four Mexican wheat varieties bred by him, which were first sown in the trial fields of IARI and the new agricultural universities at Pantnagar and Ludhiana. By 1966-67, farmers were planting these in large scale and India, from being an importer, turned self-sufficient in wheat. Much of its wheat imports earlier, ironically, came from the US under its Public Law 480 food aid programme!

Why did the US help India?

Borlaug’s International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center or CIMMYT at Mexico was primarily funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The latter, along with the Ford Foundation, also supported the International Rice Research Institute at Philippines. Both institutions contributed significantly in trebling and quadrupling grain yields, even as India, by the seventies and early-eighties, had built a robust indigenous crop breeding programme – thanks to investments in the ICAR and state agricultural universities system.

What made the US so much interested in India’s agricultural development the way the Soviet Union promoted its industrialization? Even the idea of an MSP – “a guaranteed minimum price announced in advance of the planting season” and “a market within bullock-cart distance that will pay…when the cultivator has to sell” – was first pushed by a Ford Foundation team’s report of 1959.

The answer probably lies in the Cold War geopolitics and great-power rivalry of those times. It resulted in competition to do-good, extending to “fighting world hunger” and sharing of knowledge and plant genetic material that were viewed as “global public goods”. India, contrary to popular perception, wasn’t aligned to either bloc at least till the sixties. The strategy of “non-alignment” paid off then, just as “multi-alignment” is today.