1947: The Last Years of the British in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

The Last Years of the British Empire in India

1947: Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India

REVIEWS: Mountbatten’s ‘last chukka’

Reviewed by Bahzad Alam Khan

Dawn February 25, 2007

There is compelling historical evidence that Lord Mountbatten was not the most suitable candidate for the vice-regal responsibilities with which he was entrusted by the war-weary British Empire in its twilight years. But even the flintiest of historians did not give him the kind of harsh indictment that Lord Mountbatten — remorseful many years after the blood-drenched dismemberment of the subcontinent — himself delivered on his performance as the last viceroy of British India. His rueful soul-searching found expression at a dinner meeting with a BBC journalist shortly after the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war. The journalist’s reminiscences appeared in a British newspaper in 2004. He wrote: “Mountbatten was not to be consoled. To this day his judgment on how he had performed in India rings in my ears and in my memory. As one who dislikes the tasteless use in writing of …‘vulgar slang’… I shall permit myself an exception this time because it is the only honest way of reporting accurately what the last viceroy of India thought about the way he had done his job: ‘I f****d it up.’”

Little wonder, then, that Stanley Wolpert’s icy assessment differs very little from Lord Mountbatten’s candid appraisal of his dismal performance. The only difference is that Wolpert’s use of language in his book on the last years of the British Empire in undivided India is a little less colourful. Titled Shameful Flight — an expression employed by Sir Winston Churchill to describe the graceless manner in which the British government fled the subcontinent in 1947 — the book draws heavily on the 12 volumes that contain an extraordinarily detailed account of constitutional relations between Britain and India. Quotes culled painstakingly by Wolpert from the ‘The Transfer of Power, 1942-7’ documents have enabled him to reconstruct, with the utmost precision, the diametrically opposed and often irreconcilable viewpoints that the three principal stakeholders — the British, the Hindus and the Muslims — clung on to with great tenacity during endless roundtable conferences and tortuous negotiations.

But the sins of uncompromising political leaders were visited upon their luckless followers. As a tidal surge of refugees flowed across the erratically demarcated borders in 1947, over 200,000 fleeing migrants lost their lives. According to Wolpert, a more realistic total is at least one million. Therefore, his book is, of necessity, a heartbreaking account of missed opportunities — opportunities that stealthily tiptoed past political leaders engrossed in constitutional hair-splitting and open-ended talks. Wolpert seems to insist, rightly, that both Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohammad Ali Jinnah — he has written widely acclaimed biographies of the two — must share equal blame for the wholesale bloodshed that attended partition. They may have had solid political reasons to practise what was regarded by others, especially the British government, as confrontational politics, but their inability to at least temporarily sink their differences cost hundreds of thousands of people their lives. ________________________________________ Governor Jenkins had told him, in unequivocal terms, that the partition of Punjab was “unthinkable” and “impracticable”. ________________________________________

It can be argued with the benefit of hindsight that the Muslim League should have tried to make the 1945 Simla conference a success. Furthermore, if Mr Jinnah had not allowed former Viceroy Lord Wavell’s “fond dream of forging a viable solution to India’s communal division and political deadlock” to be rudely shattered, he would not have had to subsequently deal with a viceroy widely believed to be completely under the sway of Pandit Nehru.

And this brings us — at least according to Wolpert — to the final villain of the gory partition epic: Lord Louis Mountbatten. Wolpert describes the period between December 1946 and June 1947 as “Lord Mountbatten’s last chukka”. While it is evident that Wolpert has little admiration for Mountbatten — “His ego demanded constant adulation and unquestioning support from a team of acolytes” — the expert historian is not amused by Mountbatten’s comparison of his turbulent tenure during the British government’s last year in India to a “hard-fought polo game”. Mountbatten told the King: “The last Chukka in India — 12 goals down.”

Mountbatten may have brought the skills of a determined sportsman to bear on the partition process, but he displayed little compassion for the hundreds of thousands of people whose lives were needlessly imperilled by his selfish policy of making “fast work of his India job” so that he could rush back to his promising naval career. “Though the cabinet gave him [Mountbatten] 18 months to complete it, he never had any intention of taking so long to finish off his last chukka,” writes Wolpert, sarcastically.

Not that Mountbatten was in any doubt about the horrific consequences of his ill-conceived policy. Governor Jenkins had told him, in unequivocal terms, that the partition of Punjab was “unthinkable” and “impracticable”. Indeed, Mountbatten moved with such haste that at a June 1947 press conference he confessed that he had approved a Punjab partition plan of the Congrss without even looking at a map. Mountbatten’s ignorance was matched by that of Barrister Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who was chosen to chair the boundary commission. Wolpert points out that Radcliffe, who had never before come to India, flew out “to undertake in a month work that should have taken at least a year to do properly”. Radcliffe never returned to India and feared that both the Hindus and Muslims would try to kill him.

Wolpert’s slim volume on the final and tumultuous days of undivided India shows that the dismemberment of the subcontinent did not have to be attended by so much bloodshed. While his is a sad book, it makes a gripping read. ________________________________________

Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India

By Stanley Wolpert

Oxford University Press. Plot # 38, Sector 15, Korangi Industrial Area,

Karachi Tel: 111-693-673

ouppak@theoffice.net

www.oup.com.pk

238pp. Rs495

June

1st week of June

June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 11, 2022: The Times of India

The final 75 days leading up to India’s freedom were a frantic rush. At the beginning of June 1947, it was not even clear whether India would be partitioned. The contours of the new nation had not yet been drawn. Several other massively consequential questions were also hanging in a nervous balance.

Through the pages of the Times of India , we see how the dash to decouple a wounded empire from its biggest territory, India, decided the fate of almost half a billion people within a few weeks. In this first instalment of the series, we look at the events between June 1 and 10; later, we shall look at the weekly events leading up to August 15.

But before that, a bit of context.

Mountbatten arrives in India

New Year’s Day, 1947 was pivotal for two men who greatly influenced India's independence.

In London, Louis Mountbatten was summoned by the British prime minister and ordered to go to India as the new viceroy. Mountbatten, the 47-year-old great-grandson of Queen Victoria, had tried to wriggle out of the job. He reckoned it would be tougher than his previous posting as commander of the Allied Forces in Southeast Asia during World War II. He appealed to his cousin, King George VI, but to no avail. The hand of the man who would decide so much in the final few weeks of the British Raj was forced.

On January 1, 1947, Mahatma Gandhi embarked on a different kind of journey. The 77-year-old started a seven-week, 116-km walk across Noakhali, a densely packed Muslim-majority district south of Dhaka where communal clashes had erupted in reaction to what had happened elsewhere. Gandhi took it as a test for his principle of ahimsa , or non-violence. But the hostility he witnessed convinced him that dividing the country would lead to uncontrollable bloodshed.

At about the same time in February that Gandhi ended his walk, British prime minister Clement Attlee presented a note in parliament that was prepared mostly by Mountbatten. It proposed that Britain would leave India before June 30, 1948, no matter what. It set a deadline to what the Manchester Guardian called “the greatest disengagement in history”.

But a quarter year later, some of the most consequential terms of the disengagement were yet to be decided. Gandhi stuck to his opposition to partition, Mohammad Ali Jinnah continued to insist on it, and a handful of Congress leaders grudgingly accepted it.

The parties and the people were yet to be let in on the details. The interim government – that had been created from the Constituent Assembly in September 1946 with Nehru as prime minister – was yet to work on the plan.

What would be the shapes of the new nations? What about the territories claimed by the more than 550 kings and princes? How would the resources be divided? And which day would power be finally handed over?

June 1 – 10: Leaders negotiate in huddles, make the call Plan for partition announced: Mountbatten rushes back from

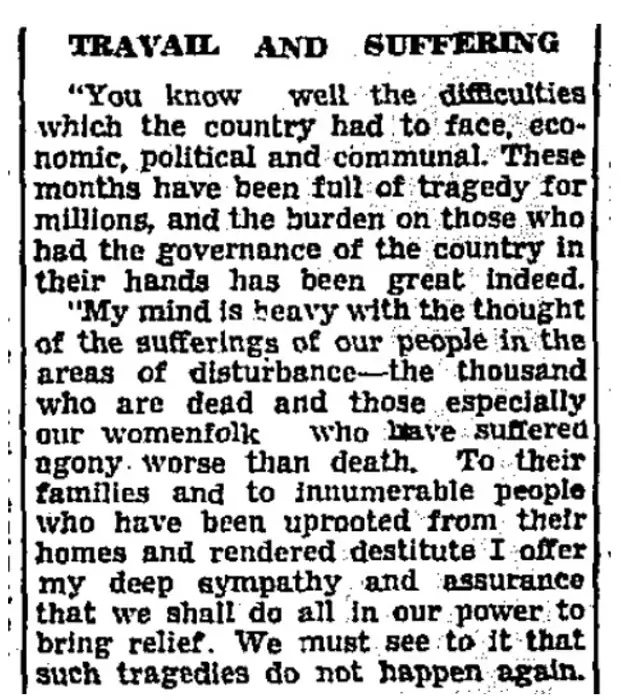

London after briefing British leaders about his initial negotiations with leaders. Back in Delhi by the beginning of June, he begins another series of hectic parleys with leaders of various parties and communities. People around the country grow restive about knowing the nation’s fate. Finally, on June 3, the basic plan for partition is announced simultaneously in Delhi and London. Nehru tells the nation: "It is with no joy in my heart that I commend these proposals to you, though I have no doubt that this is the right course. The proposal to allow certain parts to secede, if they so will, is painful for any of us to contemplate."

Sardar Baldev Singh, No 3 in the interim cabinet after Nehru and Patel, calls the plan "the best under the circumstances". The next day, at a press conference in front of 200 reporters, Mountbatten says he expects the legislative process for the handover to take place by August 15. He stays standing throughout the two-hour session and placates Indian ears with headline-worthy words: “The British will leave whenever they are told – and not asked – to leave.”

Princely states undecided on joining the Indian union: Some of India’s richest princes are yet to make up their minds about joining the union of states, while others agree on joining. This leads to an apprehension that they may leave India in a fragmented state. Some royal houses say they would prefer dominion status under the British, which Mountbatten denies, saying the Indian state would be paramount.

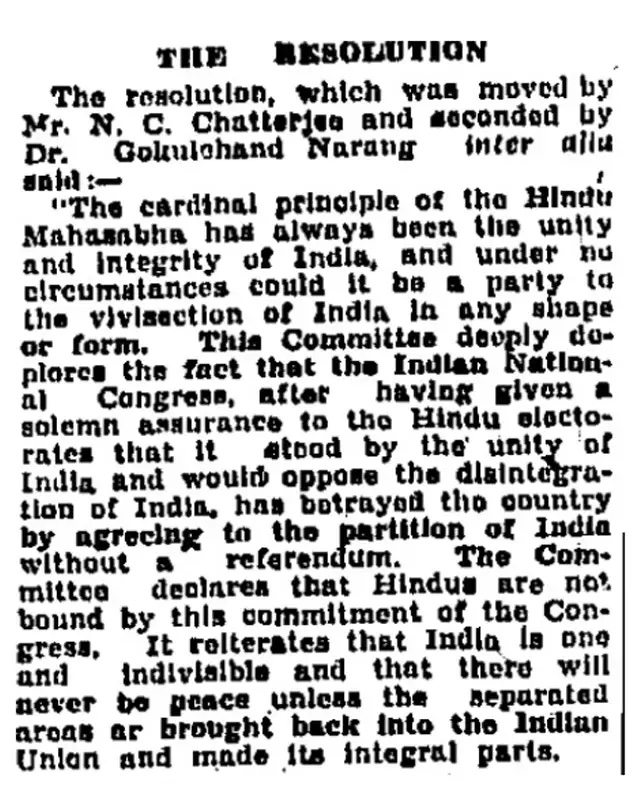

Hindu Mahasabha opposes partition: The All India Hindu Mahasabha doesn’t have a strong voice at the negotiations because of its dismal performance in the 1946 provincial elections. But on June 8, leader Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee passes a resolution opposing the partition in principle and asking for more territories in Bengal and Punjab to be given to India than initially discussed. The resolution also calls on Bengali Hindus and Sikhs to arm themselves in anticipation of the coming bloodshed.

Meanwhile in the rest of India

Increased pay for workers, textile prices to rise: An industrial court increases the basic pay of the unskilled among the 2,20,000 textile workers of Bombay to Rs 30, a third higher than earlier, based on changes in the Cost of Living Index from the pre-war era. The Kamgar Union, which had asked for Rs 33, is unhappy. The increased pay, along with promises of bonus and assured holidays would cost the city’s textile industry Rs 45 lakh a year. So a front-page story warns that the price of cloth would rise.

How India lived: Advertisements in TOI

Lux, the leading soap brand of Lever Brothers (now Unilever), pioneered celebrity endorsements in India. In 1947, they featured Ratnamala, who had starred in the 1945 biopic, Vikramaditya (1945), opposite Prithviraj Kapoor.

The government promoted National Savings Certificates heavily in the months before and after Independence to gather cash for a funds-starved treasury. The interest rate offered in 1947 was just over 4%.

Empire of India Life Assurance Company, a private insurer, celebrated its golden jubilee in India's year of independence. The company would go under administration in another 5 years as police complaints would be filed against some of its directors.

The last seven days: 9-15 August

1947: Transfer of power

Dawn August 12, 2007

EXCERPT: Transfer of power: August 1947

The date for the transfer of power came around all too quickly. We had only been in India for a little less than five months and the India that we had known for that short period was about to change for ever. Of course everyone was far too busy then to reflect upon the true significance of events as they unfolded. It was a time of excitement and raw nerves and my diary pages for those August days overflowed as I tried to capture all the momentous details. My father’s ADC, Sayed Ahsan, was a Muslim and therefore went to work for Jinnah. It was at this time, when he and the Muslim sentries and police started to leave, that I really began to understand what partition would mean for the communities.

Saturday 9th August

Immediately after breakfast there was a review of the garrison company, and the Viceregal and CC sentries and police, who are all Muslims, and so are leaving for Pakistan and will have to be replaced.

Sunday 10th August

Played with the mongoose who is very tame now and quite intoxicating and always runs about in my rooms when I am there. It is developing into rather a menace, as it chews up everything.

Monday 11th August

It was a terrible day at the clinic, very overcrowded and everyone hot and damp and extremely cross.

The Netherlands Ambassador came to present his credentials and there was a lunch party for them all afterwards.

Eric [Miéville] was there and seemed much more cheerful although still far from well.

Tuesday 12th August

I had a Hindustani lesson, but it is very difficult now that I have done all the actual grammar but still do not know enough words to be able to make conversation. We do the lessons without books, and as there is nothing else one is terribly tempted to lapse into English. As all the servants speak such good English it is therefore not a case of being able to learn through absolute necessity, and the more one practices the less time there is at the clinic.

Wednesday 13th August

We all flew to Karachi for the preliminary transfer of power ceremonies. It seemed so strange to be greeted at the airport by Sayed Ahsan [my father’s former chief ADC] The Jinnahs were in very good form and they certainly have the most lovely modern Government House. However everything was of course rather chaotic and poor Sayed was obviously having to run the whole show. When we first arrived, the town, predominantly Hindu in itself, was flying mainly Congress flags but the Pakistan Star and Crescent were eventually substituted! There was a big dinner party and reception and it seemed so queer meeting the Scotts and Yakub and various other members of our staff whom we knew well but who of course have left us.

Thursday 14th August

We went to the Ceremony at the Constituent Assembly and Mummy and Daddy drove back in state with the Jinnahs, in open cars. I drove with Begum Liaquat and there were quite thick crowds and cries of ‘Quaid-i-Azam Zinderbad’ and ‘Mountbatten Zinderbad’. Immediately afterwards we flew back to Delhi in order to be in time for the ‘Midnight Mysteries’! Tomorrow being in itself an inauspicious day we have to have part of the ceremonies at midnight. Therefore Panditji and Rajendra Prasad came after the meeting of the Assembly to ask Daddy to accept the governor-generalship.

We toasted the King-Emperor for the last time and drank the Viceroy out and the Governor-General in. By midday we said goodbye, Miss Jinnah embracing Mummy and Mr Jinnah still emotional, declaring his eternal gratitude and friendship.

The 14th August was the actual day of independence. Jinnah’s personality was cold and remote but it had a magnetic quality and the sense of leadership was almost overpowering. He made only the most superficial attempt to disguise himself as a constitutional Governor-General and one of his first acts after putting his name forward was to apply for the authority to hold immediate dictatorial powers unknown to any constitutional Governor-General representing the King. Here indeed was Pakistan’s King-Emperor, Archbishop of Canterbury, Speaker and Prime Minister concentrated into one formidable Quaid (Jinnah had very effectively quashed my father’s hopes of becoming Governor-General of Pakistan — in an attempt to retain a balanced position towards both countries — back in July.) The proceedings were over within an hour and then we drove away in state, arriving back at Government House.

Jinnah was an icy man, but on this occasion he showed emotion. He leant over to my father, put his hand on his knee and said with evident feeling, ‘Your Excellency, I’m so glad to get you back safely.’ There had supposedly been a bomb that was to be thrown during the processional drive. My father thought, ‘What do you mean? I got you back safely.’

We then flew back to Delhi. Before the Constituent Assembly met, my father was sitting at his desk waiting for Nehru and Rajendra Prasad to come to invite him formally to be Governor-General. There was an hour or two where nothing happened.

My father suddenly became aware that, as Viceroy of India, he had had enormous power, but in about an hour’s time, as a constitutional Governor-General, he would have very little indeed. It seemed a terrible waste to let this power slip away without making some use of it. Then he remembered that his dear friend the Nawab of Palampur had long entreated him to make his wife, the Begum, a ‘Highness’. The Colonial Office had always refused because she was Australian and they said it was inapplicable — even though she was enormously popular in the state and continued to do wonderful work there. So my father thought, ‘Ah, with the last power remaining to me I shall draw up an instrument and make the Begum of Palampur a Highness.’ And he did so with great satisfaction.

After the meeting of the Assembly, we toasted the King-Emperor for the last time and drank the Viceroy out and the Governor-General in. When they came with the invitation to my father, Nehru also presented him with an imposing envelope that he said contained the list of the names of the new government. After they left my father opened the envelope and found a blank piece of paper — in the rush of events someone had stuffed in the wrong piece of paper.

Friday 15th August

Independence Day. Swearing ceremony in the Durbar Hall. Daddy sworn-in as the first Governor-General of India by the new Chief Justice, Dr Kania, before himself swearing-in the members of the Cabinet Daddy has been created an Earl, so Mummy is a Countess and I have the courtesy title ‘Lady’ before my Christian name. Lovely!

The entry in my diary for the 15th August runs to four pages (not surprisingly) and the last two are written in tiny hand on the blank pages at the end of the book as it was so important that I got everything down for this most important of days.

Mummy wore a long gold lamé dress and a little wreath of gold leaves on her head. With the golden thrones and golden carpets and the red velvet canopies over the thrones spot-lit it was very sumptuous. The trumpeters in scarlet and gold had heralded a splendid entrance. At the end of the ceremony the great bronze doors were thrown open and ‘God Save the King’ was followed by the new Indian national anthem, ‘Jana Gana Mana’ — and the new Indian flag, which Panditji had described to us, was flying. Then Mummy and Daddy, escorted by the Bodyguard, drove in the state carriage down to the Constituent Assembly. I was already sitting with the staff but when the carriage arrived the Council House was entirely surrounded by a quarter of a million frenzied people chanting ‘Jai Hind’. With the laughing, cheering crowd already engulfing the carriage, it looked as though it would be impossible for Mummy and Daddy to make their entrance. Panditji and other government leaders had to be summoned to help calm the crowd and to make a passage for them. Daddy read out the King’s message to the new Dominion of India. And then he gave an address that resulted in prolonged cheers because, as one Indian said, ‘His gift for friendship has triumphed over everything.’ Then the President of the Assembly, Rajendra Prasad, read out messages from other countries, and gave an address in which he said, ‘Let us gratefully acknowledge that while our achievement is in no small measure due to our own suffering and sacrifices, it is also the result of world forces and events, and last though not least it is the consummation and fulfilment of the historic tradition and democratic ideas of the British race.’ He followed with tributes to Mummy and Daddy. After the ceremony they could not get out of the doors for some time as the crowds were still so thick. They clapped and shouted themselves hoarse with cries of ‘Pandit Mountbatten ki jai,’ ‘Lady Mountbatten’, ‘Jai Hind’ and all the popular cries for the leaders. Driving along, some even recognised me and shouted ‘Mountbatten Miss Sahib’ or even ‘Miss Pamela’ and when they did not know who one was they cheered one for being ‘Angrezi’.

In the afternoon we went to a fete for 5,000 children. It was terribly hot and, of course, very, very noisy but the children and their young parents were wildly enthusiastic. I enjoyed handing out sweets but did not enjoy the sight of a fakir apparently biting the head off a snake.

We had to rush back from Old Delhi in order to change for the Flag Salutation Parade in Prince’s Park. The programme had been arranged weeks beforehand, grandstands had been built and military parades organised, but no one had anticipated the enthusiasm of the crowds. My parents were to drive in state and I went ahead with Captain Ronnie Brockman — who had been Personal Secretary to the Viceroy and would now be Private Secretary to the Governor-General — his wife and Muriel Watson, my mother’s Personal Assistant, and Elizabeth Ward, my mother’s Personal Secretary. The Parade, however, was non-existent. The grandstands were buried under a sea of people and the only sign of the parade was a row of bright pugarees (turbans) somewhere in the centre, the men still standing at attention because the crowd was so closely packed that there was not room for them to stand at ease. There was no ceremony at all, but it was the day of the people of India and far more impressive than any pageantry could have been. We fought our way on foot from the cars to what would have been the stands had they not been buried under five hundred thousand people. There was no room to put a foot down. There was no possible space between people. In fact, it was raining babies! ‘Lots of women had brought their babies with them and they were being crushed, so they threw them up in the air in despair and you just sort of caught a baby as it came down. And some people had come with bicycles. There was no question of putting the bicycles down: they were being passed round and round overhead.

Panditji came to rescue me and led me to the tiny platform that surrounded the flagstaff. He grabbed me by the hand, but I said ‘I cannot come. Where do I put my feet? I cannot walk on people.’ He said, ‘Of course you can walk on people. Nobody will mind.’ Of course, nobody minded him walking on them but I had high-heeled shoes which would hurt a lot. So he said, ‘Well, take those shoes off, then nobody will mind.’ And he walked over human bodies the whole way, and the extraordinary thing is that nobody did mind. So I took my high-heeled shoes off, and he and I literally walked over the laughing, cheering people seated on the ground. In this way we reached the platform where I joined tiny Maniben Patel, Vallabhai’s daughter. Panditji made her and me stand with our backs against the flagstaff as he was afraid we might be knocked over in all the excitement. The state carriage finally inched its way into sight together with its own crowd and we and the whole platform were buried under a mass of shouting, pushing, sweating people, but incredibly good tempered and friendly.

The carriage could not get near, neither could the bodyguard escorting it. Daddy had to remain standing up in the carriage and salute the flag at a distance of 25 yards. Panditji had travelled back over people to try to make a passage for the carriage. Having failed, he then could not get back, so Daddy hauled him into the carriage where he sat on the hood. And they ended up having to drag four women, a child and a press photographer into the carriage as they were in danger of being crushed under its wheels. It finally left with most of the crowd running along beside it, Mummy and Daddy standing up waving and people hanging onto the carriage cheering and shaking them by the hand and throwing flowers and flags into it. The final tally was the Prime Minister riding on the hood and ten refugees crammed inside with Mummy and Daddy. When the bits of us that remained arrived back at what is now Government House I was bruised from top to bottom. But one never minded a bit. Everybody was so thrilled and excited that nothing could have mattered. We immediately went out to see the firework displays and illuminations. Afterwards there was a big Independence Day dinner party for over one hundred, followed by a reception for 2,500, each one of whom was presented to Mummy and Daddy. Quite tiring! All the state rooms and drawing rooms were open and the party overflowed into the Mughal Gardens which were floodand festooned with fairy lights, and blissfully cool. ________________________________________

Excerpted with permission from

India Remembered

By Pamela Mountbatten

Roli Books Pvt. Ltd

M-75, G.K. II Market, New Delhi-110 048

Tel: 91- 11-29212271, 29212782, 29210886

Fax: 91-11-29217185

roli@vsnl.com

www.rolibooks.com

240pp. Indian Rs1495 ________________________________________

Lady Pamela Mountbatten accompanied her parents to India, and spent the next 15 months recording the birth of two nations alongside her own transition to adulthood

See also

1947: The Last Years of the British in India