China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Photo by Ghulam Rasool/ Dawn

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

How the plan was made

KHURRAM HUSAIN | Exclusive: CPEC master plan revealed | 15 May 2017 | Dawn

Details from original documents laying out the CPEC long term plan are publicly disclosed for the first time.

Photo: by REUTERS/Faisal Mahmood, published with Dawn’s scoop about the CPEC (reproduced here). The photo was used abviously to echo the average Pakistani’s fears.

The LTP was begun in November 2013 (see detailed timeline in previous tab), when the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of the Government of China asked the China Development Bank (CDB) to compile a detailed roadmap to guide the engagement with Pakistan that had begun in May of that same year. For the next two years, till December 2015, the CDB worked with teams from the NDRC, as well the ministries of Transport, National Energy Administration and China Tourism Planning Institute to develop a detailed plan to be implemented over the next 15 years, till the year 2030, that will open the doors for Chinese enterprises – private and public – to enter every area of Pakistan’s economy.

Chinese expert teams made multiple visits to Pakistan and Xinjiang during this period, drawing up a detailed picture of the situation in every area, prioritizing those that will come first, and identifying “hidden dangers”, bottlenecks and risks that should be anticipated along the way.

The report was first transmitted to the Government of Pakistan in June 2015, where it gathered dust for a few months. Under prodding from the Chinese government, a team from Pakistan met their counterparts in Beijing on November 12th, 2015 and gave their feedback. A “special bilateral meeting” was held on Dec 2nd, and the plan finalized on Dec 29th. It was then agreed by both sides that final signatures of the highest authorities, in Pakistan’s case the Prime Minister, would be obtained by March 31st. That deadline was missed, and the signatures are expected to be placed now that the PM is in Beijing.

In the meantime, a small formality asserted itself. For the plan to be finalized, the assent of the provincial governments was required. For that purpose, a second draft was prepared that could be shared with the provincial authorities. That draft is 31 pages long and significantly watered down with all details removed, containing only broad brushstroke descriptions of the “areas of cooperation” that both countries have identified.

The original plan drawn up by the CDB is 231 pages long, and is an astonishingly detailed roadmap of the pitfalls and opportunities that Chinese enterprises can expect as they venture into every area of the economy and society. It contains specifics of what is going to be built by the Chinese over the next decade and a half, and its detailed description of Pakistan’s economy and its attendant risks shows clearly that the Chinese are fully aware of what they are getting involved in.

CPEC Long term plan: Details from original documents

KHURRAM HUSAIN| Exclusive: CPEC master plan revealed | 15 May 2017| Dawn

Details from original documents laying out the CPEC long term plan are publicly disclosed for the first time.

Plan eyes agriculture

Large surveillance system for cities

Visa-free entry for Chinese nationals

The floodgates are about to open. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif arrived in Beijing over the weekend [May 2017] to participate in the One Belt, One Road summit, and the top item on his agenda is to finalise the Long Term Plan (LTP) for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. [See next tab for details on how the plan was made].

Dawn has acquired exclusive access to the original document, and for the first time its details are being publicly disclosed here. The plan lays out in detail what Chinese intentions and priorities are in Pakistan for the next decade and a half, details that have not been discussed in public thus far.

Two versions of the Long Term Plan are with the government. The full version is the one that was drawn up by the China Development Bank and the National Development Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. It is 231 pages long.

Two versions of the Long Term Plan are with the government. The full version is the one that was drawn up by the China Development Bank and the National Development Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. It is 231 pages long.

The shortened version is dated February 2017. It contains only broad brushstroke descriptions of the various “areas of cooperation” and none of the details. It was drawn up for circulation to the provincial governments to obtain their assent. It is 30 pages long. The only provincial government that received the full version of the plan is the Punjab government.

The shortened version is dated February 2017. It contains only broad brushstroke descriptions of the various “areas of cooperation” and none of the details. It was drawn up for circulation to the provincial governments to obtain their assent. It is 30 pages long. The only provincial government that received the full version of the plan is the Punjab government.

For instance, thousands of acres of agricultural land will be leased out to Chinese enterprises to set up “demonstration projects” in areas ranging from seed varieties to irrigation technology. A full system of monitoring and surveillance will be built in cities from Peshawar to Karachi, with 24 hour video recordings on roads and busy marketplaces for law and order. A national fibreoptic backbone will be built for the country not only for internet traffic, but also terrestrial distribution of broadcast TV, which will cooperate with Chinese media in the “dissemination of Chinese culture”.

Dawn writes: The plan states at the outset that the corridor “spans Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and whole Pakistan in spatial range”. Its main aim is to connect South Xinjiang with Pakistan. It is divided into a “core area” and what they call the “radiation zones”, those territories that will feel the knock on effects of the work being done in the core area. The core area includes “Kashgar, Tumshuq, Atushi and Akto of Kizilsu Kirghiz of Xinjiang” from China, and “most of Islamabad’s Capital territory, Punjab, and Sindh, and some areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, and Balochistan” from Pakistan. It has “one belt, three passages, and two axes and five functional zones”, where the belt is “the strip area formed by important arterial traffic in China and Pakistan".

The plan envisages a deep and broad-based penetration of most sectors of Pakistan’s economy as well as its society by Chinese enterprises and culture. Its scope has no precedent in Pakistan’s history in terms of how far it opens up the domestic economy to participation by foreign enterprises. In some areas the plan seeks to build on a market presence already established by Chinese enterprises, eg Haier in household appliances, ChinaMobile and Huawei in telecommunications and China Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC) in mining and minerals.

In other cases, such as textiles and garments, cement and building materials, fertiliser and agricultural technologies (among others) it calls for building the infrastructure and a supporting policy environment to facilitate fresh entry. A key element in this is the creation of industrial parks, or special economic zones, which “must meet specified conditions, including availability of water…perfect infrastructure, sufficient supply of energy and the capacity of self service power”, according to the plan.

But the main thrust of the plan actually lies in agriculture, contrary to the image of CPEC as a massive industrial and transport undertaking, involving power plants and highways. The plan acquires its greatest specificity, and lays out the largest number of projects and plans for their facilitation, in agriculture.

The plan states at the outset that the corridor “spans Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and whole Pakistan in spatial range”. It’s main aim is to connect South Xinjiang with Pakistan. It is divided into a “core area” and what they call the “radiation zones”, those territories that will feel the knock on effects of the work being done in the core area. The core area includes “Kashgar, Tumshuq, Atushi and Akto of Kizilsu Kirghiz of Xinjiang” from China, and “most of Islamabad’s Capital territory, Punjab, and Sindh, and some areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, and Balochistan” from Pakistan. It has “one belt, three passages, and two axes and five functional zones”, where the belt is “the strip area formed by important arterial traffic in China and Pakistan".

The plan states at the outset that the corridor “spans Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and whole Pakistan in spatial range”. It’s main aim is to connect South Xinjiang with Pakistan. It is divided into a “core area” and what they call the “radiation zones”, those territories that will feel the knock on effects of the work being done in the core area. The core area includes “Kashgar, Tumshuq, Atushi and Akto of Kizilsu Kirghiz of Xinjiang” from China, and “most of Islamabad’s Capital territory, Punjab, and Sindh, and some areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, and Balochistan” from Pakistan. It has “one belt, three passages, and two axes and five functional zones”, where the belt is “the strip area formed by important arterial traffic in China and Pakistan".

Agriculture

For agriculture, the plan outlines an engagement that runs from one end of the supply chain all the way to the other. From provision of seeds and other inputs, like fertiliser, credit and pesticides, Chinese enterprises will also operate their own farms, processing facilities for fruits and vegetables and grain. Logistics companies will operate a large storage and transportation system for agrarian produce.

It identifies opportunities for entry by Chinese enterprises in the myriad dysfunctions that afflict Pakistan’s agriculture sector. For instance, “due to lack of cold-chain logistics and processing facilities, 50% of agricultural products go bad during harvesting and transport”, it notes.

A full system of monitoring and surveillance will be built in cities from Peshawar to Karachi, with 24 hour video recordings on roads and busy marketplaces for law and order.

Enterprises entering agriculture will be offered extraordinary levels of assistance from the Chinese government. They are encouraged to “[m]ake the most of the free capital and loans” from various ministries of the Chinese government as well as the China Development Bank. The plan also offers to maintain a mechanism that will “help Chinese agricultural enterprises to contact the senior representatives of the Government of Pakistan and China”.

The government of China will “actively strive to utilize the national special funds as the discount interest for the loans of agricultural foreign investment”. In the longer term the financial risk will be spread out, through “new types of financing such as consortium loans, joint private equity and joint debt issuance, raise funds via multiple channels and decentralise financing risks”.

The plan proposes to harness the work of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps to bring mechanization as well as scientific technique in livestock breeding, development of hybrid varieties and precision irrigation to Pakistan. It sees its main opportunity as helping the Kashgar Prefecture, a territory within the larger Xinjiang Autonomous Zone, which suffers from a poverty incidence of 50 per cent, and large distances that make it difficult to connect to larger markets in order to promote development. The prefecture’s total output in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery amounted to just over $5 billion in 2012, and its population was less than 4 million in 2010, hardly a market with windfall gains for Pakistan.

However, for the Chinese, this is the main driving force behind investing in Pakistan’s agriculture, in addition to the many profitable opportunities that can open up for their enterprises from operating in the local market. The plan makes some reference to export of agriculture goods from the ports, but the bulk of its emphasis is focused on the opportunities for the Kashgar Prefecture and Xinjiang Production Corps, coupled with the opportunities for profitable engagement in the domestic market.

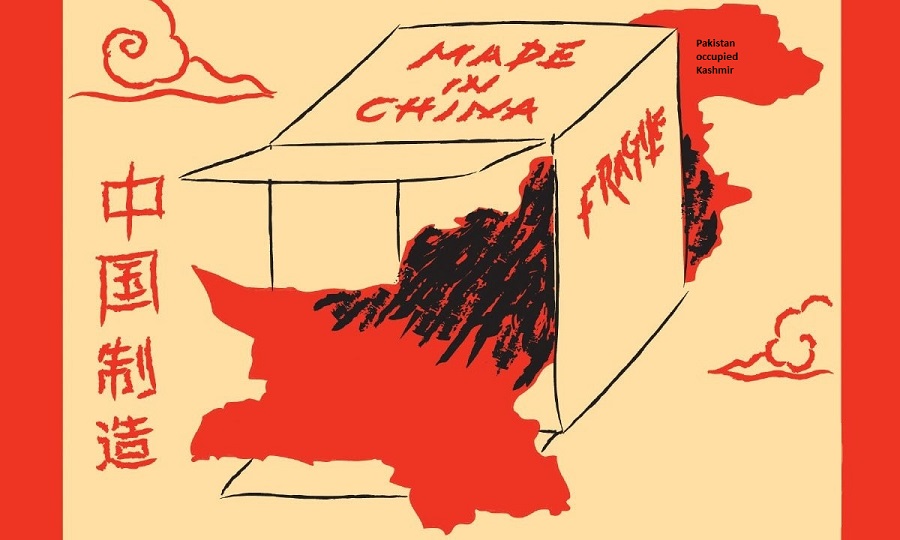

It echoes the average Pakistani’s view of what will happen to Pakistan’s sovereignty after the CPEC

The plan discusses those engagements in considerable detail. Ten key areas for engagement are identified along with seventeen specific projects. They include the construction of one NPK fertilizer plant as a starting point “with an annual output of 800,000 tons”. Enterprises will be inducted to lease farm implements, like tractors, “efficient plant protection machinery, efficient energy saving pump equipment, precision fertilization drip irrigation equipment” and planting and harvesting machinery.

The plan shows great interest in the textiles industry in particular, but the interest is focused largely on yarn and coarse cloth.

Meat processing plants in Sukkur are planned with annual output of 200,000 tons per year, and two demonstration plants processing 200,000 tons of milk per year. In crops, demonstration projects of more than 6,500 acres will be set up for high yield seeds and irrigation, mostly in Punjab. In transport and storage, the plan aims to build “a nationwide logistics network, and enlarge the warehousing and distribution network between major cities of Pakistan” with a focus on grains, vegetables and fruits. Storage bases will be built first in Islamabad and Gwadar in the first phase, then Karachi, Lahore and another in Gwadar in the second phase, and between 2026-2030, Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar will each see another storage base.

Asadabad, Islamabad, Lahore and Gwadar will see a vegetable processing plant, with annual output of 20,000 tons, fruit juice and jam plant of 10,000 tons and grain processing of 1 million tons. A cotton processing plant is also planned initially, with output of 100,000 tons per year.

“We will impart advanced planting and breeding techniques to peasant households or farmers by means of land acquisition by the government, renting to China-invested enterprises and building planting and breeding bases” it says about the plan to source superior seeds.

In each field, Chinese enterprises will play the lead role. “China-invested enterprises will establish factories to produce fertilizers, pesticides, vaccines and feedstuffs” it says about the production of agricultural materials.

“China-invested enterprises will, in the form of joint ventures, shareholding or acquisition, cooperate with local enterprises of Pakistan to build a three-level warehousing system (purchase & storage warehouse, transit warehouse and port warehouse)” it says about warehousing.

One of the most intriguing chapters in the plan speaks of a long belt of coastal enjoyment industry that includes yacht wharfs, cruise homeports, nightlife, city parks, public squares, theaters, golf courses and spas, hot spring hotels and water sports.

Then it talks about trade. “We will actively embark on cultivating surrounding countries in order to improve import and export potential of Pakistani agricultural products and accelerate the trade of agricultural products. In the early stages, we will gradually create a favorable industry image and reputation for Pakistan by relying on domestic demand.”

In places the plan appears to be addressing investors in China. It says Chinese enterprises should seek “coordinated cooperation with Pakistani enterprises” and “maintain orderly competition and mutual coordination.” It advises them to make an effort “seeking for powerful strategic partners for bundling interest in Pakistan.”

As security measures, enterprises will be advised “to respect the religions and customs of the local people, treat people as equals and live in harmony”. They will also be advised to “increase local employment and contribute to local society by means of subcontracting and consortiums.” In the final sentence of the chapter on agriculture, the plan says the government of China will “[s]trengthen the safety cooperation with key countries, regions and international organizations, jointly prevent and crack down on terrorist acts that endanger the safety of Chinese overseas enterprises and their staff.”

Industry

For industry, the plan trifurcates the country into three zones: western and northwestern, central and southern. Each zone is marked to receive specific industries in designated industrial parks, of which only a few are actually mentioned. The western and northwestern zone, covering most of Balochistan and KP province, is marked for mineral extraction, with potential in chrome ore, “gold reserves hold a considerable potential, but are still at the exploration stage”, and diamonds. One big mineral product that the plan discusses is marble. Already, China is Pakistan’s largest buyer of processed marble, at almost 80,000 tons per year. The plan looks to set up 12 marble and granite processing sites in locations ranging from Gilgit and Kohistan in the north, to Khuzdar in the south.

The central zone is marked for textiles, household appliances and cement. Four separate locations are pointed out for future cement clusters: Daudkhel, Khushab, Esakhel and Mianwali. The case of cement is interesting, because the plan notes that Pakistan is surplus in cement capacity, then goes on to say that “in the future, there is a larger space of cooperation for China to invest in the cement process transformation”.

“There is a plan to build a pilot safe city in Peshawar, which faces a fairly severe security situation in northwestern Pakistan”.

For the southern zone, the plan recommends that “Pakistan develop petrochemical, iron and steel, harbor industry, engineering machinery, trade processing and auto and auto parts (assembly)” due to the proximity of Karachi and its ports. This is the only part in the report where the auto industry is mentioned in any substantive way, which is a little surprising because the industry is one of the fastest growing in the country. The silence could be due to lack of interest on the part of the Chinese to acquire stakes, or to diplomatic prudence since the sector is, at the moment, entirely dominated by Japanese companies (Toyota, Honda and Suzuki).

Gwadar, also in the southern zone, “is positioned as the direct hinterland connecting Balochistan and Afghanistan.” As a CPEC entreport, the plan recommends that it be built into “a base of heavy and chemical industries, such as iron and steel/petrochemical”. It notes that “some Chinese enterprises have started investment and construction in Gwadar” taking advantage of its “superior geographical position and cheap shipping costs to import crude oil from the Middle East, iron ore and coking coal resources from South Africa and New Zealand” for onward supply to the local market “as well as South Asia and Middle East after processing at port.”

The plan shows great interest in the textiles industry in particular, but the interest is focused largely on yarn and coarse cloth. The reason, as the plan lays out, is that in Xinjiang the textile industry has already attained higher levels of productivity. Therefore, “China can make the most of the Pakistani market in cheap raw materials to develop the textiles & garments industry and help soak up surplus labor forces in Kashgar”. The ensuing strategy is described cryptically as the principle of “introducing foreign capital and establishing domestic connections as a crossover of West and East".

Preferential policies will be necessary to attract enterprises to come to the newly built industrial parks envisioned under the plan. The areas where such preferences need to be extended are listed in the plan as “land, tax, logistics and services” as well as land price, “enterprise income tax, tariff reduction and exemption and sales tax rate.”

Fibreoptics and surveillance

One of the oldest priorities for the Chinese government since talks on CPEC began is fibreoptic connectivity between China and Pakistan. An MoU for such a link was signed in July 2013, at a time when CPEC appeared to be little more than a road link between Kashgar and Gwadar. But the plan reveals that the link goes far beyond a simple fibreoptic set up.

China has various reasons for wanting a terrestrial fibreoptic link with Pakistan, including its own limited number of submarine landing stations and international gateway exchanges which can serve as a bottleneck to future growth of internet traffic. This is especially true for the western provinces. “Moreover, China’s telecom services to Africa need to be transferred in Europe, so there is certain hidden danger of the overall security” says the plan. Pakistan has four submarine cables to handle its internet traffic, but only one landing station, which raises security risks as well.

So the plan envisages a terrestrial cable across the Khunjerab pass to Islamabad, and a submarine landing station in Gwadar, linked to Sukkur. From there, the backbone will link the two in Islamabad, as well as all major cities in Pakistan.

The expanded bandwidth that will open up will enable terrestrial broadcast of digital HD television, called Digital Television Terrestrial Multimedia Broadcasting (DTMB). This is envisioned as more than just a technological contribution. It is a “cultural transmission carrier. The future cooperation between Chinese and Pakistani media will be beneficial to disseminating Chinese culture in Pakistan, further enhancing mutual understanding between the two peoples and the traditional friendship between the two countries.” The plan says nothing about how the system will be used to control the content of broadcast media, nor does it say anything more about “the future cooperation between Chinese and Pakistani media”.

Judging from their conversations with the government, it appears that the Pakistanis are pushing the Chinese to begin work on the Gwadar International Airport, whereas the Chinese are pushing for early completion of the Eastbay Expressway.

It also seeks to create an electronic monitoring and control system for the border in Khunjerab, as well as run a “safe cities” project. The safe city project will deploy explosive detectors and scanners to “cover major roads, case-prone areas and crowded places…in urban areas to conduct real-time monitoring and 24 hour video recording.” Signals gathered from the surveillance system will be transmitted to a command centre, but the plan says nothing about who will staff the command centre, what sort of signs they will look for, and who will provide the response.

“There is a plan to build a pilot safe city in Peshawar, which faces a fairly severe security situation in northwestern Pakistan” the plan says, following which the program will be extended to major cities such as Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi, hinting that the feeds will be shared eventually, and perhaps even recorded.

Tourism and recreation

One of the most intriguing chapters in the plan is the one that talks about the development of a “coastal tourism” industry. It speaks of a long belt of coastal enjoyment industry that includes yacht wharfs, cruise homeports, nightlife, city parks, public squares, theaters, golf courses and spas, hot spring hotels and water sports. The belt will run from Keti Bunder to Jiwani, the last habitation before the Iranian border. Then, somewhat disappointingly, it adds that “more work needs to be done” before this vision can be realized.

The plans are laid out in surprising detail. For instance, Gwadar will feature international cruise clubs that “provide marine tourists private rooms that would feel as though they were ‘living in the ocean’”. And just as the feeling sinks in, it goes on to say that “[f]or the development of coastal vacation products, Islamic culture, historical culture, folk culture and marine culture shall all be integrated.” Apparently more work needs to be done here too.

For Ormara, the plan recommends building “unique recreational activities” that would also encourage “the natural, exciting, participatory, sultry, and tempting characteristics” to come through. For Keti Bunder it recommends wildlife sanctuaries, an aquarium and a botanical garden. For Sonmiani, on the eastern edge of Karachi, “projects like a coastal beach, extended greenway, coastal villa, car camp, SPA, beach playground and a seafood street can be developed.”

It is an expansive vision that the plan lays out, and towards the end, it asks for the following: “Make the visa-free tourism possible with China to provide more convenient policy support for Chinese tourists to Pakistan.” There is no mention of a reciprocal arrangement for Pakistani nationals visiting China.

Finance and risk

In any plan, the question of financial resources is always crucial. The long term plan drawn up by the China Development Bank is at its sharpest when discussing Pakistan’s financial sector, government debt market, depth of commercial banking and the overall health of the financial system. It is at its most unsentimental when drawing up the risks faced by long term investments in Pakistan’s economy.

The chief risk the plan identifies is politics and security. “There are various factors affecting Pakistani politics, such as competing parties, religion, tribes, terrorists, and Western intervention” the authors write. “The security situation is the worst in recent years”. The next big risk, surprisingly, is inflation, which the plan says has averaged 11.6 per cent over the past 6 years. “A high inflation rate means a rise of project-related costs and a decline in profits.”

Efforts will be made, says the plan, to furnish “free and low interest loans to Pakistan” once the costs of the corridor begin to come in. But this is no free ride, it emphasizes. “Pakistan’s federal and involved local governments should also bear part of the responsibility for financing through issuing sovereign guarantee bonds, meanwhile protecting and improving the proportion and scale of the government funds invested in corridor construction in the financial budget.”

It asks for financial guarantees “to provide credit enhancement support for the financing of major infrastructure projects, enhance the financing capacity, and protect the interests of creditors.” Relying on the assessments of the IMF, World Bank and the ADB, it notes that Pakistan’s economy cannot absorb FDI much above $2 billion per year without giving rise to stresses in its economy. “It is recommended that China’s maximum annual direct investment in Pakistan should be around US$1 billion.” Likewise, it concludes that Pakistan’s ceiling for preferential loans should be $1 billion, and for non preferential loans no more than $1.5 billion per year.

It advises its own enterprises to take precautions to protect their own investments. “International business cooperation with Pakistan should be conducted mainly with the government as a support, the banks as intermediary agents and enterprises as the mainstay.” Nor is the growing engagement some sort of brotherly involvement. “The cooperation with Pakistan in the monetary and financial areas aims to serve China’s diplomatic strategy.”

The other big risk the plan refers to is exchange rate risk, after noting the severe weakness in Pakistan’s ability to earn foreign exchange. To mitigate this, the plan proposes tripling the size of the swap mechanism between the RMB and the Pakistani rupee to 30 billion Yuan, diversifying power purchase payments beyond the dollar into RMB and rupee basket, tapping the Hong Kong market for RMB bonds, and diversifying enterprise loans from a wide array of sources. The growing role of the RMB in Pakistan’s economy is a clearly stated objective of the measures proposed.

Conclusion

It is not clear how much of the plan will be earnestly followed up and how much is there simply to evince interest from the Pakistani side. In the areas of interest contained in the plan, it appears access to the full supply chain of the agrarian economy is a top priority for the Chinese. After that the capacity of the textile spinning sector to serve the raw material needs of Xinjiang, and the garment and value added sector to absorb Chinese technology is another priority.

Next is the growing domestic market, particularly in cement and household appliances, which receive detailed treatment in the plan. And lastly, through greater financial integration, the plan seeks to advance the internationalization of the RMB, as well as diversify the risks faced by Chinese enterprises entering Pakistan.

In some areas the plan seeks to build on a market presence already established by Chinese enterprises, eg Haier in household appliances, ChinaMobile and Huawei in telecommunications and China Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC) in mining and minerals.

Gwadar receives passing mention as an economic prospect, mainly for its capacity to serve as a port of exit for minerals from Balochistan and Afghanistan, and as an entreport for wider trade in the greater Indian Ocean zone from South Africa to New Zealand. There is no mention of China’s external trade being routed through Gwadar. Judging from their conversations with the government, it appears that the Pakistanis are pushing the Chinese to begin work on the Gwadar International Airport, whereas the Chinese are pushing for early completion of the Eastbay Expressway.

But the entry of Chinese firms will not be limited to the CPEC framework alone, as the recent acquisition of the Pakistan Stock Exchange, and the impending acquisition of K Electric demonstrate. In fact, CPEC is only the opening of the door. What comes through once that door has been opened is difficult to forecast.

How the CPEC will impact Pakistan

Boon for the economy, bane for the locals

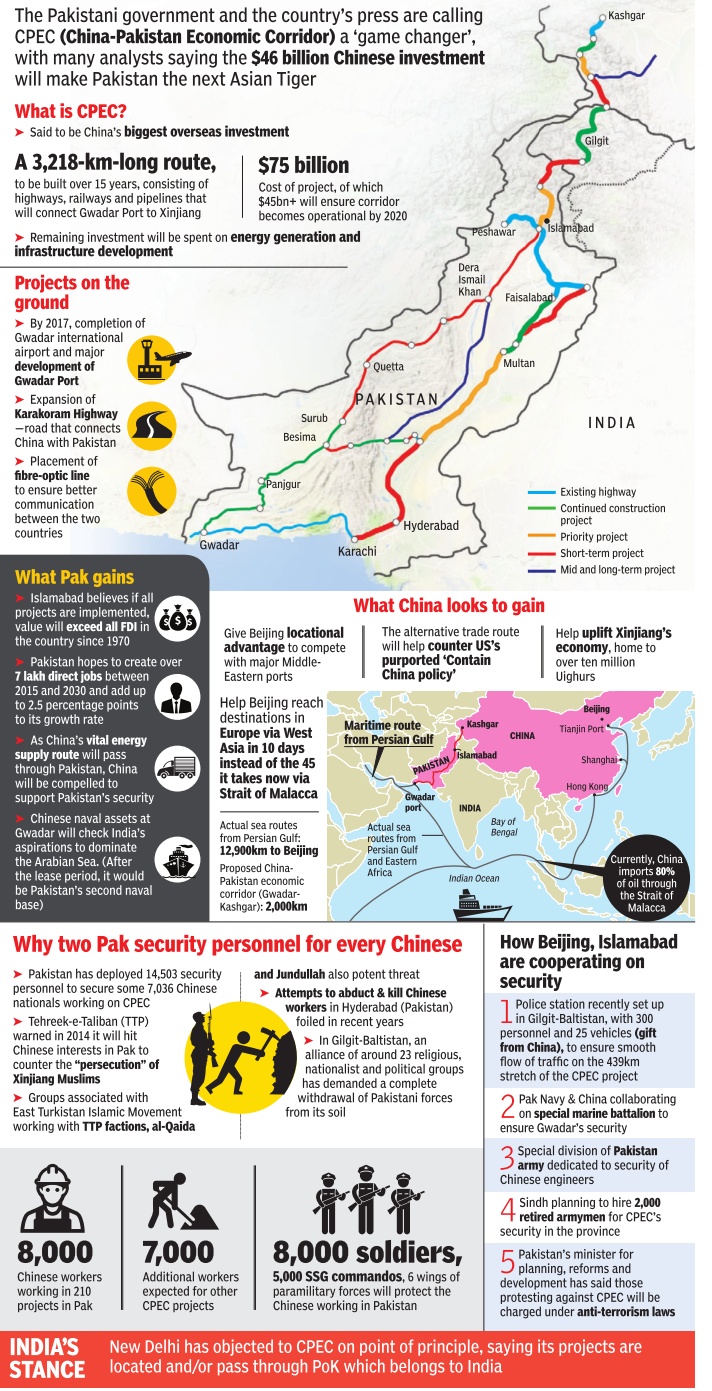

Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region is frequently in the news these days, but not necessarily for its mouth-watering cherries and dried apricots. The much touted US $46 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) will pass through this beautiful province in the north to reach Chinese-operated Gwadar port in the country's south. While there is hope it will transform the economy and help bridge Pakistan’s power shortfall, CPEC has also triggered concerns that the local people might be left out of the gains.

To be built over the next several years, the 3,218 kilometre route will connect Kashgar in China’s western Xinjiang region to the port of Gwadar. Currently, nearly 80 per cent of China’s oil is transported by ship from the Strait of Malacca to Shanghai, a distance of more than 16,000 km, with the journey taking between two to three months. But once Gwadar begins operating, the distance would be reduced to less than 5,000 km.

If all goes well and on schedule, of the 21 agreements on energy– including gas, coal and solar energy– 14 will be able to provide up to 10,400 megawatts (MW) of energy by March 2018, to make up for the 2015 energy shortfall of 4,500MW. According to China Daily, these projects should provide up to 16,400MW of energy altogether.

Businessmen like Milad-us-Salman, a resident of Gilgit-Baltistan who exports fresh fruits like cherries, apricots and apples, is hoping that CPEC will be a game-changer for the region. So far, the carefully packaged truckloads of fruit traverse the rundown Karakoram highway to reach the national capital Islamabad, from where they are flown to Qatar, Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

Last year, his company, Karakoram Natural Resources Pvt. Ltd., sold fruit worth Rs20 million (US $190,000). “We sold 30 tonnes of cherries and 100 tonnes of apples,” Salman said.

Hopes and doubts

With the CPEC passing through Gilgit-Baltistan, Salman hopes the route will open business opportunities for the region's traders.

Diverting fruit to China will be more profitable, for one, will be more profitable. “We can double our sales and profits if we can sell to China where cherries are very popular," he said.

Currently, he ships his produce to Dubai through air-cargo. "It would be faster and cheaper if we could send it by road to China via Xinjiang as we can get a one-year border pass to travel within that border," Salman explained.

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Gilgit-Baltistan produces over 100,000 metric tonnes of fresh apricots annually. While there are no official surveys, Zulfiqar Momin, who heads Farm House Pvt Ltd., which exports fresh and dried fruits to the Middle East, estimates that Gilgit-Baltistan produces up to 4,000 tonnes of cherries and up to 20,000 tonnes of apples.

“All fruits grown in Gilgit-Baltistan are organic with no pesticides used,” Momin said.

The CPEC, some believe, will also boost tourism in the 73,000 square km region. The region is considered to be a mountaineer’s paradise, since it is home to five of the ‘eight-thousanders’ (peaks above 8,000 metres), as well as more than 50 mountains over 7,000 metres. It is also home to the world’s second highest peak K2 and the Nanga Parbat.

But development consultant Izhar Hunzai, who also belongs to the area, has no such expectations. The CPEC, he feels, is nothing more than a “black hole” as far as the people of the region are concerned.

“The government has not engaged with us; we do not know exactly how much or what Gilgit-Baltistan’s role will be in CPEC or how we will benefit from it,” he said.

While both Pakistan and China will benefit through this region, he feels his people will be left “selling eggs”.

“I fear when the region opens up, it will give short shrift to the locals," he added.

Land of opportunities

But it does not necessarily have to be this way. According to Hunzai, the region has infinite water resources to tap.

“By building hydro power projects, Pakistan can sell clean energy to China and even use it for itself, the development consultant said. "If Bhutan can sell to India, why can’t we sell to China?” Hunzai poted out that the Chinese already taking the country’s national grid to its border province.

It made little sense to him that the Pakistan government wanted to buy 1,000MW of hydropower from Tajikistan under the Central Asia South Asia (CASA-1000) project and construct an expensive 750km transmission line when the resource was right there in the country’s own backyard.

However, the government is almost ready to revive the Diamer-Bhasha dam, a gravity dam on the Indus river in Gilgit-Baltistan, in the second phase of CPEC. Once completed, it is estimated to generate 4,500MW of electricity, besides serving as a huge water reservoir for the country.

Hunzai also lamented the government’s decision of buying discarded coal powered plants from China and using imported coal to run it. Doing some quick calculations on the back-of-the-envelope, he asked, “Why produce 22 cents per unit electricity from imported fuel and sell it to the people at a subsidised rate of 15 cents? Why not make electricity from hydropower which would cost just 0.02 cents?”

According to the ADB, Gilgit-Baltistan has the potential to produce nearly 50,000MW of energy. Just Bunji Dam, a run-of-the-river project that the ADB has invested in, has the capacity to generate up to 7,100MW electricity when completed.

The government is not wilfully neglecting the region, countered long-time hydropower advocate Tahir Dhindsa of the Islamabad-based Sustainable Development Policy Institute. Instead, he feels the problem is more about the profits that middlemen make. It is all about the “kickbacks and commissions” that one can earn quickly from “cheap and carbon-spewing coal power plants”, compared to almost none from hydropower projects that can take up to 10 years or more.

“The future is renewables as has been reiterated in Paris at the COP21 and Pakistan should seriously be thinking about its future course of action,” he said.

Demographic shift

There is also the fear that the CPEC may lead to widespread displacement of the locals. “Of the 73,000 square kilometres, cultivable land is just 1pc," Hunzai explained. "If that is also swallowed by rich investors from outside, we will become a minority and economically subservient once there will be no farmland or orchards left to earn our livelihood from."

He is not the only one. Given the secrecy and confusion surrounding the project, its design and its budgetary allocation, three of Pakistan’s four provinces recently held a well attended All Parties Conference (APC) and vented their anger at the central government for its opaqueness regarding the share of investments for each of the provinces.

“CPEC is not the problem. It has just highlighted the imbalance in provinces with the largest one, Punjab, being seen as favoured specially as far as investments on road infrastructure are concerned and fuelling bitterness among the rest of the three provinces,” rued Vaqar Zakaria, an energy expert heading Hagler Bailley.

Trying to address the concerns of the provinces soon after the APC, federal minister for planning, Ahsan Iqbal, who heads the Planning Commission of Pakistan, said in a television interview that this was not a time for scoring political points by making the project controversial. CPEC, he said, was not a project to benefit a party or a government as was being portrayed by politicians and the media but to the entire country.

Of the US $46bn, between $35bn to $38bn were earmarked for the energy sector– of this, $11.6bnwill be invested in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, $11.5bn in Sindh, $7.1bn in Balochistan and $6.9bn in Punjab.

Beijing has urged Islamabad to resolve the internal differences on the CPEC to create favourable working conditions for the project to roll out smoothly.

—This piece was first published on The Third Pole and was reproduced by Dawn with permission.

The economics of CPEC

ISHRAT HUSAIN | The economics of CPEC | JAN 03, 2017 | Dawn

The writer is a public policy fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Centre, Washington, D.C.

IN a country where negativity and cynicism reign supreme, critics and detractors of all kinds are revered, and emotional outbursts and fabricated stories dominate the air waves and social media, it is difficult to present a dispassionate analysis of national issues.

Since China announced the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), more time and energy has been spent in finding faults, poking holes and raising doubts based on speculation and conjecture. Had this investment been announced in another developing country, the national reaction would be: how do we plan to ensure maximisation of benefits to the economy? What are the weaknesses and deficiencies in the existing set-up we need to overcome? But this type of thinking is not in our DNA. We are either in a mood for celebration and self-congratulations or outright condemnation and depiction of exaggerated pitfalls.

There are three types of reservations against CPEC. First, those who believe that this whole endeavour is designed to benefit Punjab to the neglect of the three smaller provinces. Fanning parochial and ethnic prejudices, doubts are created about the narrow impact of these projects. Second, that the country would be saddled with costly external loans and outflows forcing Pakistan to go for another bailout. Frightening numbers such as totals of $110 billion are floating around. Third, some Baloch youth believe that they would become a minority in their own province. Mistrust and not perceived economic gains underlies such anxiety.

The government has not helped matters as it has not placed all the data and information about capital structure, detailed sources of financing, project sponsors etc pertaining to CPEC, in the public domain.

There are three types of reservations against CPEC. How can we address them?

This article, to allay some of the reservations, proposes that the Planning Commission and PIDE use the well-established framework of cost-benefit analysis to evaluate and monitor the net benefits of CPEC projects. Benefits can be of three kinds: (a) direct, measured by incremental contribution to gross value added in energy and infrastructure. Assuming energy elasticity of greater than one, a two per cent growth in energy production and usage would increase GDP by more than 2pc from the current level (b) indirect, measured by the multiplier effect of activities resulting from the direct demand of goods and services and (c) induced effects or externalities: eg bringing in roads and electricity may make some economic activities feasible and reduce outmigration of skilled labour from those areas. Costs can be of four types: (a) direct costs associated with investment in electricity generation , transmission and distribution or construction of roads; (b) indirect costs: large scale investment projects create scarcity premiums and domestic prices of some goods and services are bid up. These premiums get reduced when competition sets in; (c) unavoidable incremental costs: in the absence of the required amount of domestic supplies of quality and specifications, imports have to make up the shortfall; and (d) avoidable incremental costs: proper planning, coordination and active management can substitute high-cost inputs by low-cost inputs keeping quality intact.

Net benefits are thus estimated as the difference between the discounted flow of aggregated benefits and the discounted flow of all types of costs over the given time horizon. This calculation is not straightforward and is beset with many conceptual, empirical and measurement difficulties. The most problematic area is the aggregation of easily quantifiable direct benefits or costs with estimated indirect and induced benefits and costs. The latter are sensitive to the assumptions on which they are based. Economists, by setting up monitoring experiments, discover new data that helps in fine-tuning and refining the original estimates. The outcomes therefore depend upon minimisation of avoidable costs and expansion of induced benefits thus enlarging the quantum of net benefits.

The avoidable costs phenomenon can be illustrated with the help of two examples. If the Chinese managers, skilled and technical staff continue to be deployed throughout the duration of the project, the unit cost of labour after taking into account the expatriate wage premium, security, housing and mobility expenses would be relatively much higher compared to a situation where preponderantly Pakistanis were employed. If the government makes advance plans for these positions to be transferred to Pakistanis over a staggered period through training, on the job apprenticeship, attachments and under study assignments supervised by Chinese trainers, cost savings would be substantial and net benefits much larger. This requires coordination, target setting, monitoring and outsourcing to vocational and technical training institutes, private providers and the provincial governments.

Similarly, it is guesstimated that at least 100,000 additional trucks would be needed to transport construction materials, movement of export-import trade and increased volume of goods. If investment in the sub sector is not carried out well ahead of the CPEC projects’ peak load demand, the prices of trucking would escalate, putting Pakistani exports at a competitive disadvantage. The cost matrix of CPEC projects would also move upwards thus increasing the indirect costs. However, if Pakistani truck manufacturers are provided ballpark figures they can invest in expansion of existing capacity in tandem with the suppliers of parts and components. Indirect benefits would increase through creation of new jobs in the industry and efficiency gains from the economies of scale.

On the benefit side, it must be ensured that the most dynamic and enduring benefits from CPEC accrue to the people living in the deprived districts of Balochistan and southern KP. The opening up and integration of these districts with the unified national market of goods and services would make their fisheries, mining, livestock, horticulture and other activities economically feasible, creating incomes and jobs and helping lift them out of poverty. Roads and electricity are precursors for broad-based development as they minimise post harvest losses, waste and spoilage of perishable agriculture commodities, reduce the cost of delivery to market towns, and confer purchasing power in the hands of farmers who then use it to buy consumer goods, generating a second round of economic activities in these districts

By playing a more active role in maximising the benefits to the people of deprived districts and containing avoidable costs, the government would be able to allay a lot of misapprehensions and doubts.

Published in Dawn, January 3rd, 2017

Deloitte on how CPEC will boost Pakistan’s economy

Deloitte | How will CPEC boost Pakistan economy?

Background

According to Pakistan Economic Survey 2014-15, the volume of trade between Pakistan and China has increased to $16 billion. China’s exports to Pakistan increased by ten percent during the five years from 2009-10 to 2014-15. As a result, China’s share in Pakistan’s total exports has gradually picked up from four percent in 2009-10 to nine percent during the fiscal year 2014-15.The most recent milestone achieved in this bilateral relationship is the signing of Memorandum of Understanding on the construction of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

CPEC is a 3,218 kilometer long route, to be built over next several years, consisting of highways, railways and pipelines. The actual estimated cost of the project is expected to be US$75 billion, out of which US$45 billion plus will ensure that the corridor becomes operational by 2020. The remaining investment will be spent on energy generation and infrastructure development.

The much advertised US$45 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor will pass through the beautiful GilgitBaltistan province in the north which will connect Kashgar in China’s western province Xinjiang to rest of the world through Chinese-operated Gwadar port in the country's south. This mega project is expected to take the bilateral relationship between Pakistan and China to new heights, it’s a beginning of a journey which hopes to transform the economy and help bridge Pakistan’s power shortfall.

The CPEC project has been divided into phases, the first phase being the completion of Gwadar International Airport and major developments of Gwadar Port. This phase is expected to be completed by the year 2017.

The project also includes the expansion of Karakoram Highway- the road that connects China with Pakistan and placement of fiber-optic line ensuring better communication between the two countries. It is estimated that if all the planned projects are implemented, the value of those projects would exceed all foreign direct investment in Pakistan since 1970 and would be equivalent to 17% of Pakistan's 2015 gross domestic product. It is further estimated the CPEC project will create some 700,000 direct jobs during the period 2015–2030 and add up to 2.5 percentage points to the country's growth rate.1

Benefits

The CPEC will open doors to immense economic opportunities not only to Pakistan but will physically connect China to its markets in Asia, Europe and beyond. Almost 80% of the China’s oil is currently transported from Strait of Malacca to Shanghai, (distance is almost 16,000 km and takes 2-3 months), with Gwadar becoming operational, the distance would reduce to less than 5,000 km. If all goes well and on schedule, of the 21 agreements on energy– including gas, coal and solar energy– 14 will be able to provide up to 10,400 megawatts (MW) of energy by March 2018. According to China Daily, these projects would provide up to 16,400 MW of energy altogether.

As part of infrastructure projects worth approximately $11 billion, and 1,100 kilometer long motorway will be constructed between the cities of Karachi and Lahore,2 while the Karakoram Highway between Rawalpindi and the Chinese border will be completely reconstructed and overhauled. The Karachi–Peshawar main railway line will also be upgraded to allow for train travel at up to 160 kilometers per hour by December 2019.3

Pakistan's railway network will also be extended to eventually connect to China's Southern Xinjiang Railway in Kashgar.4 A network of pipelines to transport liquefied natural gas and oil will also be laid as part of the project, including a $2.5 billion pipeline between Gwadar and Nawabshah to transport gas from Iran.5

Oil from the Middle East could be offloaded at Gwadar and transported to China through the corridor, cutting the current 12,000 km journey to 2,395 km. It will act as a bridge for the new Maritime Silk Route that envisages linking 3 billion people in Asia, Africa and Europe, part of a trans-Eurasian project. When fully operational, Gwadar will promote the economic development of Pakistan and become a gateway for Central Asian countries, including Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, linking Sri Lanka, Iran and Xinjiang to undertake marine transport.6

Over $33 billion worth of energy infrastructure will be constructed by private consortia to help alleviate Pakistan's chronic energy shortages,7 which regularly amount to over 4,500MW,8 and have shed an estimated 2-2.5% off Pakistan's annual GDP.9With approximately $33 billion expected to be invested in energy sector projects, power generation assumes an important role in the CPEC project. Over 10,400MW of energy generating capacity is to be developed between 2018 and 2020 as part of the corridor's fast-tracked "Early Harvest" projects.10

1 Pakistan Times

2 Karachi to Lahore Motorway Project Approved". Dawn. The Dawn Media Group. 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014

3 Railway track project planned from Karachi to Peshawar". Pakistan Tribune. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2016 and nation.com.pk/national/22-Jun-2015/cpec-may-get-extra-billion-dollars "CPEC may get extra billion dollars"] Pakistan: The Nation. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

4 Zhen, summer (11 November 2015). "Chinese firm takes control of Gwadar Port free-trade zone in Pakistan". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

5 Shah, Saeed (9 April 2015). "China to Build Pipeline From Iran to Pakistan". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 December 2015

6 The Jakarta Post

7 Malik, Ahmad Rashid (7 December 2015). "A miracle on the Indus River". The Diplomat. Retrieved 11 December 2015

8 Electricity shortfall increases to 4,500 MW". Dunya News. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015

9 Kugelman, Michael (9 July 2015). "Pakistan's Other National Struggle: Its Energy Crisis". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 December 2015

10 Parliamentary body on CPEC expresses concern over coal import". Daily Time. 19 November 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015. The region of Baltistan is known for its fresh fruit exports, like cherries, apricot and apples, CPEC will be a game changer by opening business opportunities for the region's traders. This will provide local traders with an advantage and help them double their sales by tremendous saving in cost of transportation. Presently, fruits are being exported through air-cargo via Dubai it would be faster and cheaper if the same could be sent by road to China via Xinjiang.

Tourism which currently makes up an insubstantial part of our earnings is believed to be elevated by opening of this economic corridor. The CPEC, some believe, will also boost tourism in the 73,000 square km region. The region is considered to be a mountaineer’s paradise, since it is home to five of the ‘eight-thousands’ (peaks above 8,000 meters), as well as more than 50 mountains over 7,000 meters. It is also home to the world’s second highest peak K2 and the Nanga Parbat.11

K2, Pakistan. K2 is the second-highest mountain on Earth, after Mount Everest. It is located on the border between Baltistan, in the Gilgit–Baltistan region of Pakistan, and the Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang, China.

Conflicts between motives

The project surrounded by all optimism yet cannot be totally perceived without apprehensions. Government of Pakistan (GoP) claims to revive Diamer-Bhasha dam on Indus River in Gilgit –Baltistan, in the second phase of CPEC, resulting in the production of 4500MW of electricity in addition to serving as a huge water reservoir for the country, which being authenticated by Asian Development Bank (ADB), Gilgit-Baltistan has the potential to produce nearly 50,000MW of energy. Just Bunji Dam, a run-of-the-river project that the ADB has invested in, has the capacity to generate up to 7,100MW electricity when completed. The question being raised in the mind of the commoners are when by building hydro projects Pakistan can safely import energy and will have enough to use it for its development also why construct an expensive 750km transmission line?

There is also the fear that the CPEC may lead to widespread displacement of the locals. “Of the 73,000 square kilometers, cultivable land is just 1pc. If that is also swallowed by rich investors from outside, we will become anminority and economically subservient once there will be no farmland or orchards left to earn our livelihood from," Hunzai –a local businessman expressed concern while talking to Giligit Times.

11 Gilgit Tims

Not only by the local businessmen but serious concerns have been raised by various sectors and many political parties on the opaqueness regarding the project. “CPEC is not the problem. It has just highlighted the imbalance in provinces with the largest one, Punjab, being seen as favored specially as far as investments on road infrastructure are concerned and fueling bitterness among the rest of the three provinces,” repented Vaqar Zakaria, energy sector expert and managing director of environmental consultancy firm Hagler Bailley Pakistan.

Justifying the parity it is clarified by GoP that of the US $46bn, between $35bn to $38bn were earmarked for the energy sector– of this, $11.6bnwill be invested in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, $11.5bn in Sindh, $7.1bn in Baluchistan and $6.9bn in Punjab.12Repeated assurances of the Federal Government as to the parity of the project and that no province or region of the country would be discriminated in CPEC, doubts still remain as to its fair allocation.

The Final Route

After evaluating various possible routes, The All Party Conference held in May 28, 2015 unanimously decided to adopt a modified Western Route for CPEC that would pass through:

Gwadar-Turbat-Hoshab-Panjgur-Besima-Kalat-Quetta-Qila Saifullah-Zhob-Dera Ismail Khan-Mianwali-AttockHasanabdal-and onwards

This route is considered better than other routes in terms of opportunity cost of land and dislocation compensation costs.

12 Gilgit

For many Pakistanis, the CPEC is a one-way street

Reuters |For Pakistanis, China 'friendship' road runs one way The Times of India, Aug 2, 2017

HIGHLIGHTS

For many Pakistani businessmen, the China-Pakistan Friendship Highway is just a one-way street.

"There is no benefit for Pakistan. It's all about expanding China's growth," said a businessman.

While both countries say the project is mutually beneficial, data shows a different story.

TASHKURGAN (Tashkurgan is the headquarter of the Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County, Xinjiang, China.): The China-Pakistan Friendship Highway+ runs over 1,300 kilometres (800 miles) from the far western Chinese city of Kashgar through the world's highest mountain pass and across the border.

For China, the two-lane thoroughfare symbolises a blossoming partnership, nourished with tens of billions of dollars of infrastructure investment.

But for many Pakistani businessmen living and working on the Chinese side of the border, the road is a one way street.

"China says our friendship is as high as the Himalayas and as deep as the sea, but it has no heart," said Pakistani businessman Murad Shah, as he tended his shop in Tashkurgan, 120 kilometres from the mountain pass where trucks line up to cross+ between China's vast Xinjiang region and Pakistan.

"There is no benefit for Pakistan. It's all about expanding China's growth," Shah said, as he straightened a display of precious stones.

The remote town of around 9,000 is at the geographic heart of Beijing's plans to build a major trade artery — the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — connecting Kashgar to the Arabian Sea port of Gwadar.

The project is a crown jewel of China's One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative+ , a massive global infrastructure programme to revive the ancient Silk Road and connect Chinese companies to new markets around the world.

In 2013, Beijing and Islamabad signed agreements worth $46 billion to build transport and energy infrastructure along the corridor, and China has upgraded the treacherous mountain road better known as the Karakoram Highway.

While both countries say the project is mutually beneficial, data shows a different story.

Pakistan's exports to China fell by almost eight percent in the second half of 2016, while imports jumped by almost 29 percent.

In May, Pakistan accused China of flooding its market with cut rate steel and threatened to respond with high tariffs.

"There are all of these hopes and dreams about Pakistan exports," said Jonathan Hillman, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

"But if you're connecting with China, what are you going to be exporting?"

One answer is Nigerian "male enhancement" supplements: expired medications which Pakistani merchants in the oasis city of Hotan recently peddled to bearded Muslims walking home from Friday prayers.

The products were typical of the kinds of small consumer goods brought by Pakistani traders into Xinjiang: medicine, toiletries, semi-precious stones, rugs and handicrafts.

Pakistani businessmen in Xinjiang see few benefits from CPEC, complaining of intrusive security and capricious customs arrangements.

"If you bring anything from China, no problem," said Muhammad, a trader in the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar, who declined to give his full name.

But he said tariffs on imported Pakistani goods are "not declared. Today it's five percent, tomorrow maybe 20. Sometimes, they just say this is not allowed".

Three years ago, Shah was charged between eight and 15 yuan per kilo to bring lapis lazuli, a blue stone. The duty has since soared to 50 yuan per kilo, he said.

Customs officials said the "elements influencing prices were too many" for them to offer a "definite and detailed list" of costs.

While large-scale importers can absorb the tariffs, independent Pakistani traders have benefited little from CPEC, said Hasan Karrar, political economy professor at the Lahore University of Management Sciences.

Alessandro Ripa, an expert on Chinese infrastructure projects at Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, said the highway "is not very relevant to overall trade" because "the sea route is just cheaper and faster".

The project is better understood as a tool for China to promote its geopolitical interests and help struggling state-owned companies export excess production, he said.

Traders also face overbearing security in China.

Over the last year, Beijing has flooded Xinjiang, which has a large Muslim population, with tens of thousands of security personnel and imposed draconian rules to eliminate "extremism".

Businessmen complain they are not allowed to worship at local mosques, while shops can be closed for up to a year for importing merchandise with Arabic script.

In June, on the 300 kilometre trip between Kashgar and Tashkurgan, drivers were stopped at six police checkpoints, while their passengers had to walk through metal detectors and show identification cards. Signs warn that officials can check mobile phones for "illegal" religious content.

Police officers interrupted an interview in Tashkurgan to demand a shopkeeper hand over his smartphone and computer for inspection, an event he said occurs several times a week.

Shah said that when he first arrived in the town, the intrusive security made him nervous: "But now I'm used to it. I almost feel like I'm one of the police."

As he spoke, an alarm sounded. He grabbed a crude spear, body armour and a black helmet off his counter and rushed into the street, where police had assembled over a dozen people for impromptu counter-terrorism drills.

The exercises are held up to four times a day. Stores are closed for several days if they do not participate.

'China exporting debt through Silk Road projects'

HIGHLIGHTS

IMF chief Christine Lagarde has warned China about saddling other countries with a "problematic increase in debt" through its $1 trillion Belt and Road initiative The project has already hit roadblocks in a number of countries including Pakistan and Sri Lanka

International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief Christine Lagarde warned China on Thursday about saddling other countries with a "problematic increase in debt" through its ambitious global trade infrastructure project.

Lagarde made the comments at a Beijing forum on Chinese President Xi Jinping's signature Belt and Road initiative, a $1 trillion road, rail and construction project spanning dozens of countries -- from Asia to Africa and Europe.

But many of the colossal projects are being built by state-owned Chinese companies and financed by loans from China, leaving states billions of dollars in debt to Beijing.

"These ventures can also lead to a problematic increase in debt, potentially limiting other spending as debt service rises, and creating balance of payment challenges," Lagarde told the crowd of Chinese and foreign officials.

"In countries where public debt is already high, careful management of financing terms is critical," she said.

ROADBLOCKS FOR 'SILK ROUTE' IN PAKISTAN AND OTHER COUNTRIES

China's plan for a modern Silk Road of railways, ports and other facilities linking Asia with Europe hit a $14 billion pothole in Pakistan when plans for the Diamer-Bhasha Dam were thrown into turmoil in November last year, when the chairman of Pakistan's water authority said Beijing wanted an ownership stake in the hydropower project. He rejected that as against Pakistani interests.

From Pakistan to Tanzania to Hungary, projects under President Xi Jinping's signature "Belt and Road Initiative" are being canceled, renegotiated or delayed due to disputes about costs or complaints host countries get too little out of projects built by Chinese companies and financed by loans from Beijing that must be repaid.

In some areas, Beijing is suffering a political backlash due to fears of domination by Asia's biggest economy.

"Pakistan is one of the countries that is in China's hip pocket, and for Pakistan to stand up and say, 'I'm not going to do this with you,' shows it's not as 'win-win' as China says it is," said Robert Koepp, an analyst in Hong Kong for the Economist Corporate Network, a research firm.

Some countries like Sri Lanka have already ended up deeply in debt and been left with little choice but to turn over crucial assets to Beijing as way to restructure the loans.

In Sri Lanka's case, the island nation handed over a long term lease on the strategically located and bustling Hambantota Port to pay down debt.

On Thursday, Lagarde advocated greater transparency and cooperation to get all stakeholders on the same page to avoid such problems.

"It's not a free lunch, it's something where everybody chips in, it's not just honey for bees," she said, warning that the large scale spending projects also come with corruption temptations for officials.

"Projects can always present the risk of potentially failed projects and the misuse of funds. In some corners, it's even called corruption," Lagarde told the officials, many of whom preside over Belt and Road projects.

The speech may ruffle feathers in Beijing where leaders have heaped praise on the project and been loathe to acknowledge any risks or pitfalls in the initiative, which is often described as a revival of the ancient Silk Road trade routes.

Speaking before Lagarde, China's central bank chief Yi Gang said Chinese banks had "achieved great successes" providing low cost financing to Belt and Road countries.

Yi said the banks do not rely on government subsidies but at the same time are "not purely commercial lending".

Xi struck back at criticism of his key initiative on Wednesday at the Boao Forum for Asia, a Davos-like meeting of international leaders held on the southern island of Hainan.

The Belt and Road "is neither the Marshall Plan after World War II nor an intrigue of China. It is, if anything, a plan in the sunshine," Xi said, according to the Xinhua state news agency.

A transit, economic or development corridor: A Spanish- Pakistani study

ARI 53/2016 -

This paper is jointly published with Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad

Theme

What are the prospective implications of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) on Pakistani development and regional stability?

Summary

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor provides an excellent opportunity for improving the economic and security situation in Pakistan and its neighbouring countries. However, such an outcome cannot be taken for granted. This paper analyses the steps that should be taken to favour this scenario and warns about the consequences that a poorly-managed implementation of the CPEC might have, such as aggravating divisions within Pakistan and heightening tensions between Islamabad and other regional players.

Analysis1

Since its announcement in July 2013, probably no policy initiative is receiving more attention in Pakistan than the CPEC. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has reiterated on several occasions that CPEC could be a game changer for Pakistan and the entire region.2 Along the same lines, Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Minister, has described the CPEC as the ‘flagship project’ of the One Belt, One Road initiative,3 Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy project.4 Moreover, there is a widespread consensus among the Pakistani military, political parties and society at large on the enormous potential of the CPEC for spurring economic growth in the country.

Indeed, the US$46 billion package of projects contained in the CPEC offers an exceptional opportunity to Pakistan for tackling some of the main barriers hindering its economic development: energy bottlenecks, poor connectivity and limited attraction for foreign investors. According to the Agreement on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Energy Project Cooperation between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, signed on 8 November 2014, 61% of the CPEC investment will be allocated to energy projects aiming to improve energy-system capacity and the transmission and distribution network. Thus, Pakistan may be able to terminate with what a Wilson Centre report labelled ‘Pakistan’s Interminable Energy Crisis’,5 which according to their estimates has cost its economy 2% to 2.5% of GDP annually. Only in the early harvest phases (2017-18), CPEC projects are expected to add 10,400MW to the Pakistani energy system.

Up to 36% of CPEC funding will be devoted to infrastructure, transport and communication. It is evident that a greater connectivity will create new opportunities for development in Pakistan, since, according to the Planning Commission, the poor performance of transport sector costs the Pakistani economy 4% to 6% of GDP every year.6 The improvement in communications will be important both for a greater integration of the domestic market and for facilitating Pakistani exports. In addition, the CPEC will help to improve the confidence of international investors in Pakistan, whose image of the country is not always in line with current situations and tends to be more negative than merited by actual conditions. In the words of the former Economic Minister of the Pakistani Mission to the EU, Safdar Sohail, ‘Pakistan has turned a page in terms of terrorism and regional integration and the Chinese investment is a way of sending that message’.

Obstacles

The massive prospective benefits that the CPEC can bring to Pakistan are contingent to its actual implementation, which faces serious obstacles. One of the most obvious is the security situation, despite the improvements experienced on that front during the past two years. The most well-known pro-independence Baloch leaders have denounced the negative impact they believe CPEC will have in Balochistan and some have even warned China ‘to stay away from Gwadar’.7 Beijing’s concerns on this issue made the Pakistani authorities announce, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Islamabad in April 2015, the creation of a 12,000-strong force devoted to protecting Chinese interests and nationals in Pakistan.8 This new Special Security Division is funded by Pakistan, although certain well-informed sources have suggested that China will provide some equipment. Moreover, Rs45 billion is expected to be spent in fiscal year 2016 on raising the security unit and on Operation Zarb-e-Azb.9 This is a key issue, since Beijing has become more sensitive over the past years to attacks against Chinese nationals on foreign soil.

The CPEC’s security is also closely interlinked with regional geopolitics, particularly with India’s stance on the initiative and on the stabilisation of Afghanistan. In India many voices have raised concerns about the CPEC, and even the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, criticised the project as ‘unacceptable’ during his visit to Beijing in June 2015.10 Indian reservations are mainly related to certain CPEC transport projects crossing Gilgit-Baltistan, part of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, and the implications of China’s easier access to the Indian Ocean and how they might affect India’s security and strategic context.11 Various quarters in Pakistan believe that these misgivings have even led to cooperation between Indian security agencies and Pakistani militants, especially following the arrest in Balochistan in March 2016 of an alleged officer of the Research and Analysis Wing.12

This is not to deny that the CPEC can offer incentives for India to improve its relations with Pakistan, since the corridor could facilitate Indian access to Central Asia.13 In other words, the CPEC is not only threatened by security conditions within and without Pakistan, but can also contribute to improving them. The potential contribution of the CPEC to regional stability is more evident at present with regard to Afghanistan. Peace in Afghanistan is a key factor for the success of the CPEC and the reduction of international support for the East Turkestan Independent Movement militants. These are the main reasons of Chinese decision to participate in a joint effort with the governments of the US, Pakistan and Afghanistan to revive the Afghan peace process.14 This direct Chinese involvement in seeking a political settlement to the war in Afghanistan contrasts with Beijing’s avowed policy of non-interference before launching the One Belt, One Road initiative.

Another difficulty is the lack of experience in mutual economic cooperation, since Pakistani-Chinese relations have been traditionally limited to political and military factors. This scant economic interaction is illustrated by trade and investment figures. The value of bilateral trade was below US$1 billion until 2001 and China ranked among the three main foreign investors in Pakistan during only one fiscal year (2006/07) in the previous decade.15 Therefore, it can be argued that the CPEC incorporates an economic pillar to this long and consolidated bilateral relationship and both sides are now learning how to co-operate in this field.

Scenarios

The CPEC consists of three layers including early harvest, medium term and long term projects. First two stages are in working position, whereas the long-term project will end till 2030. At the moment it is at an early phase, and its projects are expected to be completed in 2017 and 2018. This is the first of the four phases that make up the CPEC, the other three being the short-term (2020), medium-term (2025) and long-term (2030) phases. At the outset it would be difficult to assess CPEC’s impact on Pakistan, however this should be borne in mind that this is the most pertinent question with far reaching consequences.

It could be argued that even if the China-Pakistan corridor has been officially described as an economic corridor, its final nature is still far from being determined and will depend to a large extent on decisions made in Beijing and Islamabad. Three different scenarios can be envisioned: (1) a transit corridor; (2) an economic corridor; and (3) a development corridor. The China-Pakistan corridor influence on the socio-economic development of Pakistan will be determined by the kind of corridor it will become. Since Pakistan is a diverse country and the CPEC will have several different alignments (see Map 1) running through different areas, it is quite possible that its influence will vary from one area to another.

Transit corridor

A transit corridor connecting China’s western province of Xinjiang with the Indian Ocean port of Gwadar in south Balochistan was first proposed in 2006 by the then President General Pervez Musharraf.16 The corridor’s completion would serve Beijing’s interests in many ways. On the economic front, the cost of western and central China’s international trade with Central Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa will be reduced. For instance, China would save around US$2 billion every year if it were to use the CPEC to import 50% of its current volume of oil supplies.17 In addition, better connectivity and easier sea access will favour the development of Xinjiang, which the Chinese authorities considers as paramount for reducing terrorism in the region. Moreover, the transit corridor has significant geostrategic value, making China less vulnerable to US rebalancing towards Asia and an eventual blockade of the Malacca Strait. It will also facilitate the projection of China’s influence in the Indian Ocean and in Eurasia.18 Therefore, both the maritime and the land silk roads are expected to converge in the port of Gwadar.

If the CPEC is finally merely a transit corridor, its potential for fostering socioeconomic development in Pakistan will be severely limited. Even if China is offering financing through the CPEC to Pakistan in a volume and under conditions unmatched by other creditors, these are loans, not grants, and therefore Pakistan will be expected to repay them.19 The total value of China’s loans has not been disclosed, but should be quite significant, since the US$11 billion granted for infrastructure purposes will be added as a substantial share of the US$35 billion investment announced for the power sector. For instance, US$820 million of the US$2 billion committed for the Thar coal project are provided by a syndicate of Chinese banks, including the China Development Bank, the Construction Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.20

The massive transport facilities that are being – and shall be – created, extended and renovated within the framework of the CPEC will demand a notable disbursement in security and maintenance once they are completed. Security will be particularly problematic in the western alignment, as will maintenance under the severe weather and geographical conditions of the Pakistani side of the Karakorum Highway and of Balochistan. This may aggravate by its expected heavy use by lorries.

The growing Pakistani exports, the development of roadside services and transit fees could offset these financial obligations. Traditional exports such as textiles, agro-food, sporting-goods and mining are likely to benefit from the improvements in connectivity. However, more detailed sectoral analyses are needed, since some areas of the Pakistani economy, mainly the manufacturing industry, could suffer due to higher Chinese competition brought on by the CPEC. It also demands more exhaustive studies to be conducted in order to gain enough information to embark precisely on the cost-benefit analysis that should inform CPEC-related decisions: for instance, the feasibility of transit fees for Chinese oil shipments and trade traffic and the eventual volume of income they could generate.

Economic corridor

Unlike transit corridors, economic corridors are explicitly designed to stimulate economic development. In order to overcome its energy crisis, Pakistan needs to articulate an industry and trade boosting programme to gain from the CPEC in terms of additional business opportunities, apart from temporary jobs. The fact that the lion’s share of CPEC-related investment will be allocated to projects in the energy sector, to help Pakistan overcome its chronic energy crisis, is a solid indication that the China-Pakistan corridor honours its official designation as an economic corridor. Most of the energy projects are being financed under a build-own-operate model. In this scenario, Chinese investors are entering the Pakistani energy market as independent power providers with special protection guarantees. Chinese independent power-providers are assured an 18% return on their investment, whereas the rest are getting a 17% return for their equity; and some complain that this would distort the level playing field. This, like the establishment of exclusive Chinese special economic or industrial zones should be managed with extreme caution in order to avoid potential sinophobic feelings that might hinder the implementation of the CPEC. In any case, if the energy projects are implemented and the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority is able to set prices that are acceptable to investors and consumers, the spillover effect on the Pakistani economy will be colossal.