|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {| class="wikitable" | + | {| Class="wikitable" |

| | |- | | |- |

| | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> |

| − | This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/>You can help by converting these articles into an encyclopaedia-style entry,<br />deleting portions of the kind nor mally not used in encyclopaedia entries.<br/>Please also fill in missing details; put categories, headings and sub-headings;<br/>and combine this with other articles on exactly the same subject.<br/> | + | This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> |

| − |

| + | </div> |

| − | Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly <br/> on their online archival encyclopædia only after its formal launch.

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div>

| + | |

| | |} | | |} |

| | | | |

| − | [[Category: India|G]]

| |

| − | [[Category: Biography|G]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | =Philosophy, views=

| |

| − | == Champaran Satyagraha ==

| |

| − | [http://www.dailyexcelsior.com/584202-2/ Dr Sudhanshu Tripathi , Remembering Mahatma Gandhi through Champaran Satyagraha "Daily Excelsior" 30/1/2018]

| |

| | | | |

| − | Indeed, Champaran Satyagrahas marked the emergence of Mahatma from M. K. Gandhi wherefrom began a new era in India’s freedom struggle.During those days when popular protests were repressed by brute force unleashed by the British Government, the strategy of peace and non-violent persuasion in Champaran proved to be highly useful as it discouraged the English rulers from resorting to barbarity against the agitators.

| |

| | | | |

| − | With Mahatma Gandhi’s approaching martyr day very close to observe, everyone is reminded of his immense contribution towards selfless service of humanity suffering the agony and trauma of utter ignorance, poverty and wretchedness and also violence, injustice or inequality of all kinds all over the world.And that moved Gandhi’s inner core which motivated his pious self to jump into fulfilling his lifelong mission for alleviation and uplift of these millions as he could feel the inner voice of their hearts. While he was working in South Africa towards this end but his deep passion for service of own motherland brought him back to India where he began with this utter desire to serve the hapless millions.And the farmer’s agitation in Champaran against various forms of prevailing injustice provided him the required opportunity to practice his noble ideas into action wherein he proved to be very successful. In fact, the Champaran peasant movement was a part of the wider struggle prefixed for independence. When Gandhiji returned from South Africa, he wanted to experiment with his first-ever non-cooperation satyagraha,as alimited endeavour, by providing leadership to the infant peasant agitations at Champaran in Bihar and later atKheda in Gujarat. Although these struggles were taken up as reformist movements yet the underlying rationale was to mobilise the peasants towards their genuine demands meant for their survival.Indeed,Champaran Satyagraha was based on insistence on ‘truth and non-violence’,along-with persuasive strategy. It was organized as a peaceful movement in total contradiction with the violent peasant uprisings in the past. Fortunately the movement received massive support from some of the prominent leaders of the country like Rajendra Prasad, Brijkishore Prasad and Muzhar-ul-Haq who constituted the progressive intelligentsia of the then India. This provided strength and a constructive direction to the movement. Can’t it become again a role model in today’s world fraught with never-ending macabre violence and global terrorism?

| |

| | | | |

| − | In the early 19th century, European planters had set up indigo farms and factories at Champaran, in North Bihar. Thereafter, they forced the local cultivators to enter into the tinkathia system, which stipulated that out of 20 khatas which make an acre, they had to dedicate 3 khata sexclusively for indigo plantation. Though the peasants (bhumihars) of Champaran and other adjoining areas of Bihar were growing the Indigo under the tinkathia system, they had to lease this part in return to the advance at the beginning of each farming season and adding further to their woes, they were compelled to sell their crops at a throw away price which was fixed on the area cultivated by them rather than the crop produced. When the demand for indigo in the international market began to fall with the arrival of German synthetic dyes, the European planters passed the burden of losses over these cultivators, besides raising rents and extracting other illegal dues from them lest they close producing indigo. As Indigo plantation had been destroying the fertility of their soil they had nothing but to protest against such unjust farming. Consequently, the planters used illegal and inhuman methods of indigo cultivation upon the poor peasants while forcefully subjecting them to an extremely inadequate remuneration. Further these planters demanded heavy price from the peasants in lieu of relieving them from the lease contracts. Thus, as a whole, they were being bitterly cheated by the planters and the overall situation had become very horrible as well as pathetic which compelled a noted writer and documentary-maker D.G. Tendulkar to write: ‘The tale of woes of Indian ryots, forced to plant indigo by the British planters, forms one of the blackest in the annals of colonial exploitation. Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.’

| |

| | | | |

| − | Against this backdrop, an enlightened peasant in Champaran, Raj Kumar Shukla who was also suffering this highhandedness, managed to persuade Gandhiji to survey the area to standup for the cause of the exploited peasants. Hence Gandhiji and his supporters visited extensively through villages,while listening to their grievances, and recording their horror tales of repression. Thus Gandhiji could understand the inhuman misery and brutal savagery which these peasants had been suffering from in the Champaran.Hence their miseries were discussed thread-bar at the annual conference of the Bihar Provincial Congress Committee on 10th April, 1914,which concluded that the Champaran peasants were really suffering their worst. And that again motivated the Provincial Congress Committee in 1915 to recommend for constitution of an inquiry committee to assess the woes of the Champaran peasantry. As the issue had drawn countrywide attention by then, the Indian National Congress, in its Lucknow session in 1916, also discussed the Champaran case to decide for immediate remedial measures for them.

| + | =A contribution of Mahatma Gandhi= |

| | + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=100-years-on-Gandhis-Champaran-methods-remain-relevant-15042017011033 Avijit Ghosh, 100 years on, Gandhi's Champaran methods remain relevant , April 15, 2017: The Times of India] |

| | | | |

| − | Hence, Gandhiji chose to represent the peasants’ cause and initiated the Champaran peasant movement which was launched in 1917-18. Its objective was to create awakening among the peasants against the prevailing exploitation of the European planters. On 14th May, 1917 Gandhiji wrote a letter to the District Magistrate of Champaran, W.B. Heycock, wherein he showed his deep concerns about the sufferings of peasants at the hands of landlords and also the Government of the day. The peasants opposed not only the planters but also zamindars,as they were equally brute and oppressive for the peasants though Gandhiji wanted to normalize their mutual relations. Meanwhile, a Champaran Agrarian Committee had already been constituted by the Government, with Gandhiji as one of its members. As pressure mounted against such exploitation and the recorded statements of about 8,000 peasantstestified the inhuman exploitation and barbarity, the Government had to accept Gandhiji’s suggestion of abolishing the tinkathia system. The European planters had to sign an agreement granting more compensation and control over farming to these poor farmers and cancellation of revenue hikes and collection until the famine ended. Furthermore, the planters were asked to refund 25 percent of the amount they had illegally collected from the peasants as enhancement of dues.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Thus the Champaran Satyagraha became a grand success and turned to be a powerful tool of civil resistance in the ensuing India’s freedom struggle. The psychological impact of this Satyagraha was outstanding as it aroused firm belief in truth and non-violence among the suffering peasants of Champaran and also among the countrymen as well. Indeed, the satyagrah aproved to be a great morale booster to not only Gandhiji -which made him a global symbol forever – and the Champaran peasantry but became an icon of peaceful and non-violent struggle for the whole nation and also the whole world. In fact, this icon is the only option even today for survival of innocent humanity bearing the brunt of ever-recurring gruesome violence and various forms of terror, besides innumerable temporalpains and physical difficulties in every nook and corner of the world.

| + | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's struggle to bring succour to distressed peasants forced to cultivate indigo in Bihar's Champaran district happened exactly 100 years ago, but social scientists and researchers feel his methods remain relevant, even desirable, in today's fractured times. |

| | | | |

| − | (The author is Political Science, U.P. Rajarshi Tandon Open University)

| + | The Champaran struggle is a very good example of a restrained moral struggle combined with social responsibility, says Salil Mishra, who teaches history at Dr B R Ambedkar University . |

| | + | “It shows how to mobilize opinion and support for a cause without resorting to moral hysteria,“ he says. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Racism against the Africans?==

| + | Sandeep Bhardwaj of Centre for Policy Research points out that there were no marches or strikes in Champaran. “Instead of defeating the opposition, Gandhi sought to win it over through the art of political persuasion. In contrast, the tendency in today's politics is often to burn down the house to light a candle achieve a political victory by any means necessary , even if it comes at the cost of larger communal harmony ,“ says Bhardwaj, who blogs at revisitingindia.com That's why , says social scientist Ashis Nandy , Gandhi's methods remain relevant. “There is an ethical component in his actions which has tremendous power and validity ,“ he says. |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Ghanaians-want-univ-statue-of-racist-Gandhi-pulled-20092016017001 Indrani Bagchi, Ghanaians want univ statue of `racist' Gandhi pulled down, Sep 20 2016 : The Times of India]

| + | |

| | | | |

| | + | Indigo was an important crop for European planters in India. The conditions under which the peasants worked were oppressive. In his book, Gandhi in Champa ran, D G Tendulkar quotes a former magistrate of Faridpur, Mr E De-Latour of the Bengal Civil Service saying, “Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.“ |

| | | | |

| − | Anger Against Mahatma's Use Of Slur For Africans In Writings

| + | Dinabandhu Mitra's play , Nil Darpan (1860), highlights the anguish of the peasant tenants (ryots). |

| | | | |

| − | Three months after President Pranab Mukherjee gifted a statue of Mahatma Gandhi to the University of Ghana, a group of professors and students have started a petition to bring it down.

| + | “The story of Champaran begins in the early 19th century,“ writes Mridula Mukherjee in `India's struggle for Independence', “when European planters had involved the cultivators in agree ments that forced them to cultivate indigo on 320th of their holdings (known as the tinkathia system).“ |

| | | | |

| − | The opposition centres around their belief that Gandhi was “inherently racist“ for his depiction of native black Africans as “kaffir“ (considered a racial slur in Africa) in his early writings, when he was fighting for the rights of Indians in South Africa. | + | The peasants had to pay enhanced rents over a period (sarahbeshi) or simply get out of the system paying a lump sum (tawan). |

| | | | |

| − | According to reports, some members of the university , led by a former director of the Institute of African Studies, Professor Akosua Adomako Ampofo, have started a campaign to get the institution to pull down the statue, which was unveiled during a visit by President Pranab Mukheriee in June. natures, which comes as an embarrassment to the Indian government.

| + | Gandhi arrived by train at Motihari in Bihar's Champaran district on April 15, 1917. He had come to the region following the request of Raj Kumar Shukla, a local cultivator. The next day, he was asked to leave.He refused, was taken into custody and summoned to court on April 18. |

| | | | |

| − | The campaign carries the slogan `Gandhi Must Fall' and `Gandhi For Come Down' (pidgin for Gandhi Must Come Down), inspired by the “Rhodes Must Fall“ campaign against a statue of Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University .

| + | When Gandhi pleaded guilty, the colonial government was nonplussed. Unwilling to make him a martyr, authorities decided to withdraw the case and let him continue to gather statements of cultivators. On April 21, the case was withdrawn. |

| | | | |

| − | The statue was installed at the recreational quadrangle of the university's Legon campus in Accra.

| + | “Armed with evidence collected from 8,000 peasants, he had little difficulty in convincing the Commission that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and that the peasants should be compensated for the illegal enhancement of their dues,“ writes Mukherjee. |

| | | | |

| − | Apart from a campus agitation, a petition to the university authorities on change.org has already attracted 872 signatures in a bit of a quandary . The site was chosen by the Ghana foreign office when the President went for a visit in June. While there are some voices preaching moderation, the ministry of external affairs is also waiting to see whether the campaign gathers steam.

| + | Misra points out that Champaran was the first systematic effort to introduce the peasant question into the nationalist politics. |

| | | | |

| − | '''The offensive passages ''' | + | “Till then the two had proceeded apart from each other.Nationalist politics was almost `peasant neutral' and peasant protests were local and spontaneous. Gandhi, who was an outsider to Champaran, introduced satyagraha and organised politics in the rural areas. He thus combined the rural with the national,“ he says. |

| | | | |

| − | One of Gandhi's writings that have been cited in the petition reads thus: “A general belief seems to prevail in the Colony that the Indians are little better, if at all, than savages or the Natives of Africa. Even the children are taught to believe in that manner, with the result that the Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.“ (Dec 19, 1894) A second, more damaging (Sept. 26, 1896) one reads: “Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.“ (The petitioners have sourced the quotes from Gandhi and South African Blacks http:www.gandhiserve.orgecwmgcwmg.htm ) Putting an international spin to their petition, they listed a number of colleges and universities around the world seeking to remove the overt symbols of racism.

| + | “It was also at Champaran that Gandhi applied his techniques of satyagraha (perfected in South Africa) in India for the first time.Champaran should be seen as the first political laboratory in India where Gandhi made his experiments in satyagraha and then replicated them in other places (polite but firm defiance of the authority , basing struggles not simply on emotions and grievances but concrete enquiry and fact-finding, among others),“ he says. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Religion==

| + | And as Mahatma Gandhi himself wrote in his autobiography , “The Champaran struggle was a proof of the fact that disinterested service of the people in any sphere ultimately helps the country politically .“ |

| − | === Organised religion vs. ethical/ moral practices===

| + | |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=the-speaking-tree-Recalling-Gandhijis-Perspective-On-Religion-02102017016056 Ashok Vohra, Recalling Gandhiji's Perspective On Religion, October 2, 2017: The Times of India]

| + | |

| | | | |

| − |

| + | ==Fighting To Keep Gandhi’s Memories Alive== |

| − | MK Gandhi was aware of the difficulties in defining the term `religion'. He took pains to explain it in a number of his writings over several years. He was aware that the term religion can be, and is, used in two senses to refer to organised religion and to refer to ethical or moral practices that have their root in a specific ontology and metaphysics.

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL/2019/09/25&entity=Ar00400&sk=95D3B430&mode=text Anam Ajmal , Sep 25, 2019: ''The Times of India''] |

| | | | |

| − | He uses the term in both these senses. In `Hind Swaraj' he says, “Religion is dear to me ... Here i am not thinking of the Hindu ... or the Zoroastrian religion, but of that religion which underlies all religions.“ That Gandhi does not use the term religion to connote such individual religions or faiths is clear when he says, “By religion, I do not mean formal religion, or customary religion, but that religion which underlies all religions, which brings us face to face with our Maker.“

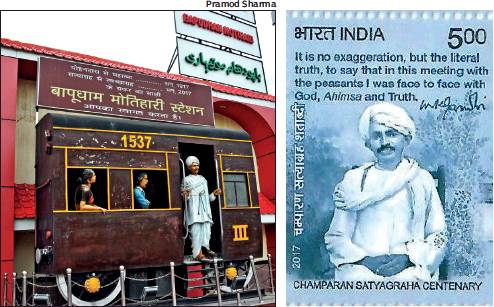

| + | [[File: A display about Gandhi at the Bapudham Motihari Station (left) in Champaran. A commemorative stamp (right) released in 2017 to mark 100 years since the Champaran Satyagraha.jpg|A display about Gandhi at the Bapudham Motihari Station (left) in Champaran. A commemorative stamp (right) released in 2017 to mark 100 years since the Champaran Satyagraha <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL/2019/09/25&entity=Ar00400&sk=95D3B430&mode=text Anam Ajmal , Sep 25, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] |

| | | | |

| − | Elaborating on his use of the term `religion' further, he says, “Religion does not mean sectarianism. It means a belief in ordered moral government of the universe.“ According to him, religion is that “which transcends“ the limits of any particular religion. It does not supersede individual religions like Hinduism, Islam, Christianity ... but “harmonises them and gives them reality“.

| + | How Champaran’s Indigo Kicked Off Gandhi’s Freedom Struggle |

| | | | |

| − | This kind of religion is one “which changes one's very nature, which binds one nature, which binds one indissolubly to the truth within, and which ever purifies. It is a permanent element in human nature which counts no cost too great in order to find full expression and which leaves the soul utterly restless until it has found itself, known its Maker and appreciated the true correspondence between the Maker and itself.“

| + | Bapu’s Karmabhoomi Fights To Keep His Memories Alive |

| | | | |

| − | Gandhi in `Hindu Dharma' explains this: “All of us with one voice call God differently as Parmatma, Ishwara, Shiva, Vishnu, Rama, Allah, Khuda, Dada Hormuzada, Jehova, God, and an infinite variety of names. He is the One and yet many; He is smallest, smaller than an atom, and bigger than the Himalayas. He is contained even in a drop of the ocean, and yet not even the seven seas can encompass Him.“

| + | Once a proud mansion, Belwa Kothi now wears the sadness of a ruin. The roof has surrendered to time, and the plaster is peeling. Close at hand lies a crumbling factory overrun by wild grass, forsaken like a stale idea. |

| | | | |

| − | That Gandhi does not regard religion or being religious or following of a religious order or creed as something external, some kind of a `job' or `profession' is abundantly clear when he asserts, “I do not conceive religion as one of the many activities of mankind.“ The main reason for this is that “the same activity may be governed by the spirit, either of religion or of irreligion.“

| + | But for this sleepy village in Bihar’s East Champaran district, these two buildings are reminders of its tryst with history. In the early 20th century, the factory was managed by a British officer AC Ammon and extracted neel (indigo), which farmers of the region were forced to cultivate on 15% of their land. |

| | | | |

| − | Gandhi regards being religious as something inherent to humankind. The term religion, as used by him pervades all our activities. Therefore, he concludes, “For me every , tiniest activity is governed by what i consider to be my religion.“ He explicitly admits this fact when he says, “This is the maxim of life which i have accepted, namely , that no work done by any man, no matter how great he is, will really prosper unless he has a religious backing.“

| + | The oppressive system, known as tinkathia, was widely despised. Raj Kumar Shukla, a local farmer, drew Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s attention towards the exploitative system. Gandhi arrived in Bihar in April 1917, and Champaran became his first karmabhoomi in India. A worried Bettiah BDO wrote that Gandhi was “daily transfiguring the imaginations of masses of ignorant men with visions of an early millennium.” During those days of struggle, Gandhi had stayed for a night in Belwa. |

| | | | |

| − | Gandhi's notion of religion is `metaphysical or the ideal'. In this context, there can be no conflict between religions because it assumes that there is just one universal religion or that there is just one religion underlying all religions. Then, the word religion would be always used in singular and never in the plural. | + | While in Champaran, Gandhi shuffled between the district’s two main towns, Motihari and Bettiah. He travelled across the hinterland, recording statements of 8,000 cultivators. He convinced the Commission of Inquiry set up by the government that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and ensured that the planters refunded 25% of the amount they had taken illegally from farmers. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Satyagraha and The Three Monkeys==

| + | That was then. Now, Belwa lives on memories, and rues unfulfilled promises. Shukla’s grandson, Mani Bhushan Roy, who still lives in his grandfather’s ancestral village, is skeptical about what has been achieved post-Independence. “We have electric poles, but no electricity. And we have roads that flood during monsoons,” he says. He keeps Shukla’s red hard-bound pocket diary in a black polythene bag and opens it sometimes to remind government officials of the role his grandfather played in the freedom struggle. |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=the-speaking-tree-Gandhijis-Satyagraha-And-The-Three-02102015024048 ''The Times of India''], Oct 02 2015

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | K M Gupta

| + | To celebrate 100 years of that landmark moment in the national movement, busts of Gandhi and Kasturba were installed in Belwa by Bihar’s minister of rural development Shrawan Kumar in 2018. Just a few months later, Gandhi’s statue was beheaded by anonymous miscreants. “We have written to the administration several times after that, but no action has been taken to restore it,” a Belwa resident says. |

| | | | |

| − | ''' One way of fighting evil is not to shut it out from our senses '''

| + | Many places associated with the Champaran struggle are also gone. At the house of Gorakh Prasad in Motihari, Gandhi stayed and compiled farmers’ testimonies. The house, which served as Gandhi’s base, was razed to construct a new house. |

| | | | |

| − | Granted, there is so much evil in the world corruption, nepotism, terrorism, for instance. But it is beyond us to change what is widespread. We have seen even well-intentioned people entering politics to cleanse it and then getting sucked into its vortex. It is a misconception that the world was good in the past, and it has worsened only now. The world was always the same and will be always so, perhaps.

| + | The residence of another freedom fighter, Ram Babu Kedia, who hosted Gandhi on various occasions, has been converted into a school though the students remain unaware of its history. “We have heard our grandfathers say that Gandhiji stayed in this building. But these are private properties now, and the owners can use them as they see fit. These buildings could have been preserved only by the government, but no attention has been paid to them,” a teacher at Shikshayatan School said. |

| | | | |

| − | So, do we accept evil, surrender to it?

| + | Yet, some are fighting to keep Gandhi’s spirit alive. For the past 20 years in Motihari, celebrations of the Mahatma’s life start a week before his birth anniversary. Tarkeshwar Prasad, who owns a general store, organises a “puja” on October 2. The whole town participates in the event, which starts with a prabhat pheri at 7am. Participants circle the town market first and then come to the pandal, where Gandhi’s statue is installed. “Gandhiji is like God for us. He did not just fight for independence; his fight was for the entire world because it showed everyone the importance of truth and non-violence,” says Prasad. Adds history enthusiast Bhairab Lal Das, who works as the project officer at Bihar Legislative Council, “The first chapter of the freedom movement started in Champaran. We need to restore places visited by Gandhiji to create public awareness and evoke a sense of pride.” Das has translated Shukla’s diary, which was written in Kaithi script, into Hindi. |

| | + | The homes where the leader visited might still be repaired but Gandhians lament that the Mahatma’s ideals are lost. Says Braj Kishore Singh, the 87-year-old secretary of the Gandhi museum in Motihari, “Today Gandhi survives, but only in museums and parks, on currency notes and in songs. His message of truth is no longer followed.” |

| | | | |

| − | Certainly not. There is a passive way of fighting evil and making the world a little more beautiful. In Japan, Kobe College's department of psychology conducted an experiment: they divided students into two groups. The first group was required to do nothing but carry on as usual. The second group was asked to just observe the good deeds done by people around them helping an elderly person to get into or out of public transport, feeding birds and animals, nursing a hurt bird or animal, and indulging in other acts of compassion and kindness. Small things; not great sacrifices or exceptionally kind deeds. After some time, it was found that the happiness levels of the second group registered a marked jump. The conclu sion was: even just observing the kind deeds of others increases one's happiness level.

| + | ==Champaran and the making of the Mahatma== |

| | | | |

| − | In science, the term `observer effect' refers to the effect an observer has on the observed by his act of observation.For example, to check the pressure in an automobile tyre, a little air needs to be released.This affects the pressure in the tyre. That is the observer effect.The result of the Japanese study is the reverse of the observ study is the reverse of the observer effect. The observed influences the observer's mind.

| + | Just two years after he returned from South Africa... |

| | | | |

| − | So we can raise our happiness level free of cost. There are small streams, though not great rivers, of the milk of human kindness flowing all around us.Just by observing them, our happiness levels rise. Money and materials can create conditions conducive for happiness, but cannot exactly conduct it.

| + | Gandhi visited Champaran in April 1917 after learning of how cultivators there were being forced by British colonialists to grow indigo against their will under unfair terms |

| | | | |

| − | This influence of observing good deeds can, and does, go beyond just a rise in one's happiness level.

| + | His opening shot was to hold a survey |

| | | | |

| − | As we observe good deeds of others, not only does our happiness level rise, we start aping the good deeds of others unconsciously . We begin to radiate the goodness we experience. The observed becomes the observer.

| + | Gandhi collected testimonies and statements of thousands of farmers on the atrocities and abuses inflicted on them by the British landlords |

| | + | And he armed people with knowledge, awareness of rights |

| | | | |

| − | When we are good at heart, in thought, word and deed, we start lactating the milk of human kindness. We start from observing the goodness of others and aping it and end up being aped by others. This cycle of goodness boosts the happiness level of society as a whole. The more the absorption and radiation, the less would be the evil around us.This is one silent but viable way of fighting evil, and it is not difficult.

| + | During his stay in Champaran, Gandhi helped open three basic schools as he felt the people needed to be literate and learn about their rights. He also organised training in farming and other skills to promote self-reliance |

| | | | |

| − | When he started his non-violent movement in South Africa, Gandhiji first named it passive resistance. Then he felt the term to be tame and likely to be misunderstood and so he switched to the term satyagraha. The silent absorption and radiation of goodness discussed above is close to Gandhiji's idea of passive resistance.

| + | In six months, Gandhi had made his point |

| | | | |

| − | Observing the goodness around us and absorbing it as a habit requires shutting our senses to the evil around us as far as possible. That is where Gandhiji's Three Apes come in: see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. In Japan, the three mystic apes are called Mizaru, Kikazaru and Iwazaru.

| + | Faced with the testimonies from Gandhi, an official Champaran inquiry committee was set up of which Gandhi himself was made a member. The committee submitted its report in October 1917 with recommendations that favoured the peasants. Finally, coercive indigo cultivation ended with the passage of a law in March 1918 |

| − | ==Sex: Kusoom Vadgama on Gandhi ji and sex==

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | ''' `Gandhi was obsessed with sex ¬while preaching celibacy to others' '''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=QA-Gandhi-was-obsessed-with-sexwhile-preaching-celibacy-16082014012025 The Times of India ] Aug 16 2014

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A controversy has erupted in Britain over the proposed second statue of Gandhiji in London, this one in Parliament Square. ''' Kusoom Vadgama, ''' the doughty historian (born: 1932) and former `Gandhi worshipper', told Bachi Karkaria at age 82 why she is leading the fight brigade against the statue.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '' On Gandhi's `debasement of women' by his experiments with sexual self-control. ''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Kusoom Vadgama: Men in position of power take advantage of their status. They have no qualms about abusing minors or women. All his life Gandhi was obsessed with sex ¬while preaching celibacy to others. No one challenged him. He was the nation's `untouchable' hero, his iconic status eclipsed all his wrong doings. The protest against yet another statue of his in London, just two miles from the one in Tavistock Square, is a perfect opportunity to speak the truth about this other people's Mahatma.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi never made a secret of sleeping naked with his greatgrand daughter and the wife of his great-grand son. It may have been his way of testing his control over his sexual drive, but these women were used as guinea pigs. If he had used other adult women, it would have been nothing more than interesting gossip. But Gandhi chose a teenage blood relation and a great-grand-daughter-in-law for his sexual whims. I have no fear or hesitation in telling the truth about him. Ironically , it was he who instilled in me the mantra of `satyameva jayate'.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi's darker side was ignored but never forgotten.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''But Gandhiji did give a great deal of space to women in the freedom struggle. For them it was a personal liberation. ''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Kusoom Vadgama: Gandhi mobilised the women of India. One of the reasons for his success was that his political rallies were called prayer meetings. Women attended in thousands not only to listen to him but also to have the `darshan' of the saintly man.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''Earlier, Kusoom Vadgama too `worshipped Gandhi'. ''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He was Kusoom Vadgama’s God in Nairobi,Kenya, where both her parents were deeply involved in India's free dom movement.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In school, Kusoom Vadgama stud ied the glory and great ness of the British Empire, but spent all her time outside in protest marches and dawn processions, ordering the British out of India. she even shouted `Jai Hind' to the English school teacher, and thought she would be expelled.

| |

| − | == Spirituality: How it shaped Mahatma Gandhi==

| |

| − | [http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/books/How-spirituality-shaped-Mahatma-Gandhi/articleshow/29545360.cms? IANS] | Jan 29, 2014

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Title: ''' Gandhi: A Spiritual Biography '''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Author: Arvind Sharma

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Publisher: Hachette India

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Pages: 252

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Price: Rs.550

| |

| − |

| |

| − | This work captures the spiritual side of a man who played probably the most important role in helping India to become a free nation. The weapons he used were unique: truth and non-violence. This, author Arvind Sharma says, was part of his innate spirituality.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | For Gandhi, morality and religion were synonymous. He made it amply clear that what he wanted to achieve was self-realization, "to see God face to face, to attain Moksha". His earliest influences came from Hindu lore. His parents were devout worshippers of the god Vishnu. It was part of this influence that Gandhi learnt to repeat the name of Rama - a Vishnu 'avatar'- to get rid of his fear of ghosts and spirits!

| |

| − |

| |

| − | But Gandhi was no Hindu fanatic. He respected all religions equally. The New Testament made a definite impression on him. Theosophy made a deeper impact. He battled for Muslims. He was a true religious pluralist. But "if he did not find Christianity perfect, neither did he find Hinduism to be so". It was his faith in spirituality that clearly gave him the courage to act the way he did on so many occasions, even when it looked as if he was treading a lonely path.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi would say that the thread of life was in the hands of God. But unlike most Hindus he did not believe in idols. At the same time he worshipped the Bhagavad Gita - calling it his "mother" in later life. Even Nathuram Godse saw Gandhi as a saint - but a saint gone wrong and deserving to die.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The book has one gaping hole. There is surprisingly no reference to Paramhansa Yogananda, an iconic Indian saint whose "Autobiography of a Yogi" (published in 1946) is still considered a spiritual classic. Yogananda moved to the US in 1920 and for three decades preached Kriya Yoga and meditation to tens of thousands. On a short trip to India, he spent time with Gandhi at Wardha and taught the Mahatma and his aides Kriya Yoga. It was probably the only yoga Gandhi learnt. A self-realized guru, Yogananda called Gandhi a saint. I am surprised how Sharma overlooked this important spiritual chapter in Gandhi's life in an otherwise informed book.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Friends, international=

| |

| − | ==Hermann Kallenbach and Gandhi==

| |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=TOI-INTERVIEW-Kallenbach-was-Gandhis-wailing-wall-Researcher-30092015025043 ''The Times of India''], Sep 30 2015

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Kounteya Sinha

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''' ''Kallenbach was Gandhi's `wailing wall': Researcher'' '''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Priceless documents discovered in Israel have revealed, for the first time ever, the role a Jewish architect played in creating the phenomenon that was Mahatma Gandhi. When Lithuania unveils the statue of Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach in Rusne on October 2, researcher Shimon Lev of Jerusalem's Hebrew University, who has extensively studied the archive, will reveal to the world the story of the deep friendship between India's father of the nation and his “soulmate“. Excerpts from Lev's exclusive interview to TOI:

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''How did you get your hand on the Gandhi Kallenbach documents?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Some years ago, I wrote a series of articles about a hiking trail across Israel. During my hike, in a cemetery near the Sea of the Galilee, I went to see the neglected grave of Kallenbach.I published a few lines about him, which resulted in an invitation from his niece, Mrs Isa Sarid, to “have a look“ at Kallenbach's archive. The archive was located in a tiny room in a small apartment up on Carmel Mountain in Haifa. On the shelves were numerous files carrying the name of Gandhi. One of the less known chapters of Gandhi's early biography was waiting for a researcher to pick up the challenge. Finding an archive like this might be the fantasy of any historian.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''You call Gandhi and Kallenbach soulmates. Were they truly?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Their friendship was characterized by mutual efforts towards personal, moral and spiritual development, and a deep commitment to the Indian struggle. On a personal level, Kallenbach provided Gandhi with sound emotional support. He was Gandhi's confidant, with whom Gandhi could share even the most personal matters, such as troubles with his wife and children. Gandhi's letters to Kallenbach and documents in the archive reveal their relationship to be an extremely complex and highly unconventional one, with elements of political partnership and surprisingly strong personal ties for two such dissimilar men.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Any interesting anecdotes fom their lives that show their proximity to each other?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Kallenbach was Gandhi's “wailing wall“. When Harilal, Gandhi's eldest son, ran away to Delgoa Bay on his way to India in an effort to get the formal education his father denied him, it was Kallenbach who was sent to bring him back.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''What was the unique historical significance in their encounter?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | I think that one of most important contributions of Kallenbach is the establishment of Tolstoy Farm in 1910.It is impossible to over-emphasize the influence of the experiment on the formulation of Gandhi's spiritual and social ideologies. But what made their story even more unique was the “second round“, which took place in 1937, when Hitler was already in power. Kallenbach was asked by future Israeli PM Moshe Sharet to brief Gandhi on Zionism, hoping to get his support for a Jewish homeland. That is when Gandhi came out with the disturbing proclamation, The Jews, in 1938, in which he called the Jews to begin civil resistance and be ready to die as a result. Gandhi used Kallenbach as an example of the tension between his nonviolence doctrine and what was going on in Europe.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | “I happen to have a Jewish friend...He has an intellectual belief in non-vi olence. But he says he cannot pray for Hitler. I do not quarrel with him over his anger...“

| |

| − |

| |

| − | So the chronicles of their relationship traverse the dramatic events of the first half of the 20th century.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''What was unique about this relationship and why isn't their relationship so widely known?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Kallenbach was Gandhi's most intimate European supporter. He was the one who Gandhi could mostly trust.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | There may be a number of reasons for the general disregard of Kallenbach's contribution. Their forced separation due to Kallenbach's confinement in a British internment camp during World War I is partly to blame.Had Kallenbach gone to India, it is probable that he would have become the administrative manager of Gandhi's Indian ashrams. Moreover, the scarcity of first-hand sources regarding their relationship makes the study of his influence difficult.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''Who inspired whom in the relationship and how?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Obviously, Gandhi was the one who inspired everyone else around him, including Kallenbach. He was the spiritual authority no doubt about this. Kallenbach's Jewish family regarded him as one trapped by “Gandhi's spell“.

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''How will this statue help in telling their stories?'''

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Well, definitely it will make their fascinating story more known. I claim that it is impossible to understand Gandhi without understanding his relationships with those close to him.Between 1906 and 1909, Gandhi underwent an extremely significant transformation, the result of which was that his doctrine became fully solidified. His partner in these crucial years was Herman Kallenbach.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | == Nelson Mandela on the Mahatma==

| |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=the-speaking-tree-Divinely-Inspired-Extraordinary-Leader-30012017018046 Nelson Mandela, Divinely Inspired Extraordinary Leader, Jan 30 2017: The Times of India]

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Mahatma Gandhi was no ordinary leader. There are those who believe he was divinely inspired, and it is difficult not to believe with them. He dared to exhort non-violence in a time when the violence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had exploded on us; he exhorted morality when science, technology and the capitalist order had made it redundant; he replaced self-interest with group interest without minimising the importance of self. In fact, the interdependence of the social and personal is at the heart of his philosophy . He seeks the simultaneous and interactive development of the moral person and society .

| |

| − |

| |

| − | His philosophy of Satyagraha is both a personal and social struggle to realise the Truth, which he identifies as God, the Absolute Morality . He seeks this Truth, not in isolation, self-centredly , but with the people.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He sacerises his revolution, balancing the religious and the secular.He resuscitated the culture of the colonised; he revived Indian handicrafts and made these into an economic weapon against the coloniser in his call for swadeshi the use of one's own and the boycott of the oppressor's products, which deprive the people of their skills and their capital.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi's insistence on self-sufficiency is a basic economic principle that, if followed today , could contribute significantly to alleviating Third World poverty and stimulating development.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi predated Frantz Fanon and the black-consciousness movements in South Africa and the US by more than a half century and inspired the resurgence of the indigenous intellect, spirit and industry .

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi rejects the Adam t Smith notion of human nature as motivated by self-interest and brute needs and returns us to our spiritual dimension with its impulses for nonviolence, justice and equality .

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He exposes the fallacy of the claim that everyone can be rich and successful provided they work hard. He points to the millions who work themselves to the bone and still remain hungry .

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He seeks an economic order, alternative to the capitalist and communist, and finds this in Sarvodaya based on Ahimsa non-violence.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He rejects Darwin's survival of the fittest, Adam Smith's laissez-faire and Karl Marx's thesis of a natural antagonism between capital and labour, and focusses on the inter dependence between the two.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He believes in the human capacity to change and wages Satyagraha against the oppressor, not to destroy him but to transform him, that he cease his oppression and join the oppressed in the pursuit of Truth.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | We in South Africa brought about our new democracy relatively peacefully on the foundations of such thinking, regardless of whether we were directly influenced by Gandhi or not.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi is not against science and technology , but he places priority on the right to work and opposes mechanisation to the extent that it usurps this right ... He seeks to keep the individual in control of his tools, to maintain an interdependent love relation between the two, as a cricketer with his bat or Krishna with his flute. Above all, he seeks to ... restore morality to the productive process.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | At a time when Freud was liberating sex, Gandhi was reining it in; when Marx was pitting worker against capitalist, Gandhi was reconciling them; when the dominant European thought had dropped God and soul out of the social reckoning, he was centralising society in God and soul; at a time when the colonised had ceased to think and control, he dared to think and control; and when the ideologies of the colonised had virtually disappeared, he revived them and empowered them with a potency that liberated and redeemed.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Ideological differences=

| |

| − | ==Dr Ambedkar, Vir Savarkar==

| |

| − | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL/2019/09/28&entity=Ar01000&sk=4B374A3B&mode=text Vaibhav Purandare, Sep 28, 2019: ''The Times of India'']

| |

| − |

| |

| − | For one so wedded to peace, Mahatma Gandhi’s constant companion in life was the tempest. Often it blew all too ferociously, inviting for him charges of preaching from the pulpit, sidetracking the freedom movement in favour of obscure moral questions, pandering to the Hindu majority or Muslim minority, talking down to Dalits and talking up the virtues of non-violence to the point of discrediting India’s armed revolutionaries.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | His protracted battles with the British and with Jinnah are well known. So is the exasperation his proteges like Nehru, Patel and Bose sometimes felt over his approach. Unfairly for both Gandhi and his opponents, though, Indian textbooks, for long after Independence, barely informed new generations about his differences and debates with two of his staunchest and most unsparing Indian critics: BR Ambedkar and VD Savarkar.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Savarkar appeared on the scene before Ambedkar, when Gandhi was in South Africa. As the young leader of a group of patriotic Indians in London, he met Gandhi first in 1909 when the latter visited the British capital, and together, they heaped praise on each other at a public meeting. Both then affirmed their faith in Hindu-Muslim unity, but they had fundamental differences: Savarkar embraced revolutionary methods in the struggle for liberation, and Gandhi abhorred violence. On his way back to South Africa, Gandhi wrote on the ship his tract ‘Hind Swaraj’, in which he voiced his disapproval of armed revolution. Savarkar’s reply: “We aren’t fond of violence, but if constitutional methods are denied to us, how else do we fight for our rights?”

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Soon, Savarkar was dispatched to Kaala Paani. By the time he was back in a jail on the mainland in 1921 and later placed in conditional confinement in 1924, everything had changed. Gandhi had taken over the Swaraj movement and got the masses to adopt his mantra of non-violence. Worse for Savarkar — now a man transformed after experiences with Pathan jail staffers in the Andamans — Gandhi had openly backed the “pan-Islamic” Khilafat agitation. This was not Khilafat but an “aafat (trouble)”, Savarkar said, and termed the non-cooperation movement and its sudden withdrawal as “eccentric and defeatist politics”.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | They discussed their differences in 1927 during Gandhi’s visit to Savarkar’s Ratnagiri home and agreed to go separate ways. Savarkar then wrote a series of essays assailing the Mahatma for his “hollow” Ahimsa absolutism, his “fetish” for goat’s milk, his “needless meddling in politics (in the 1930s) after declaring he’d focus on the charkha,” his opposition to railways and modern medicine, and his invocation of “Ram Rajya” and “cow protection”. Though by now author of the tract Hindutva, Savarkar was no believer in “gau mata”; his Hindutva was political. Gandhi had previously made an appeal for Savarkar’s release from Kaala Paani; asked in the mid-1930s to issue another plea for end of his conditional confinement, he refused, saying “my way of moving in such matters is different”.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Ambedkar, who earned his spurs at Columbia University, shared with Savarkar a dislike for Gandhian projections of a religious morality. Both also felt Gandhi was wrong in defending the caste system. Ambedkar saw the word ‘Harijan’, coined by Gandhi for the Depressed Classes, as patronising and left his first meeting with the Mahatma in 1931 in a huff after Gandhi opposed the Raj’s plan for separate electorates for the ‘outcastes’. Ambedkar was firm on political safeguards, while Gandhi considered the “political separation of Untouchables” from Hindus “suicidal”. Months later, at the Second Round Table Conference, Ambedkar accused Gandhi of “treachery” against the Depressed Classes, said he had “created a scene” during debate, and dubbed him “petty-minded”. Gandhi’s “fast unto death” amid this row, and the 1932 Poona Pact between the two caused a permanent breach — Dalits got more seats but no separate electorates.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The paths of Ambedkar and Savarkar too diverged drastically, with the former declaring he was “born a Hindu but wouldn’t die as one”, and Savarkar in 1937 assuming leadership of Hindu Mahasabha. Both, however, struggled to create an alternative pole in Indian politics even as they intensified attacks on Gandhi. Ambedkar called Gandhi’s politics — like Savarkar once had — “hollow”, “noisy”, “the most dishonest … in the history of Indian polity”, and Savarkar criticised him for his “Quit-India-but-keep-your-arms-here plea” to the British and for giving parity to Jinnah in negotiations.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Savarkar and his followers ultimately blamed Gandhi for “presiding over Partition”. When the Constitution took shape, Ambedkar, for his part, was relieved India hadn’t adopted a Gandhian Constitution with the village (in Ambedkar’s words “a den of casteism and superstition”) as a central unit, but one in the European-American tradition. Still, Ambedkar struggled politically against Congress until his death in 1956, and Savarkar’s arrest in the Gandhi assassination case ruined his political career in spite of his acquittal.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | To Gandhi’s credit, he had sought to engage with both critics while still on talking terms with them, telling them he’d visit their place for discussions if it were inconvenient for them to come over. With Savarkar, there was at least some initial warmth; with Ambedkar, there was none.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[Category:Biography|G

| |

| − | MAHATMA GANDHI]]

| |

| − | [[Category:India|G

| |

| − | MAHATMA GANDHI]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Welfare=

| |

| − | ==1924: Raising funds for Kerala==

| |

| − | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/when-mahatma-gandhi-mobilised-rs-6000-for-flood-relief-in-kerala/articleshow/65549938.cms When Mahatma Gandhi mobilised Rs 6,000 for flood relief in Kerala, August 26, 2018: ''The Times of India'']

| |

| − |

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Nearly a century ago when floods ravaged Kerala, Mahatma Gandhi had termed the misery of the people as "unimaginable" and stepped in to mobilize over Rs 6,000 to help them, records show.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | If the present rain fury has claimed over 290 lives and displaced over 10 lakh people + , the massive floods that crippled the state in July 1924 are believed to have claimed a large number of lives and caused widespread destruction.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Mahatma Gandhi, through a series of articles in his publications 'Young India' and 'Navajivan', had urged people of the country to generously contribute for the relief of the flood-hit' Malabar' (Kerala).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Following his appeal, people from various walks of life including women and children had donated even their gold jewels and meagre savings to help the flood-affected people.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Many had skipped a meal daily or given up milk to find money to contribute to relief fund mobilized by Gandhi, according to the journals penned by him.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The "Father of the Nation" had mentioned in one of his articles in 'Navajivan' about a girl who had stolen three paise to contribute to the relief fund.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "Malabar's misery is unimaginable," Mahatma had said in the article titled "Relief Work in Malabar."

| |

| − |

| |

| − | He said he had to "confess" that the response to his appeal had been "more prompt" than he expected.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "It has been proved not once but many times that, by God's grace, compassion does exist in the hearts of the people."

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Many funds had been launched for collecting relief amounts and people could contribute whichever one they choose.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "I would only urge that pay, they must," Mahatma Gandhi had said.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The massive flood that lasted for around three weeks in July 1924 had crippled and submerged various parts of the then Kerala including hilly Munnar, Trichur (Thrissur now), Kozhikode, Ernakulam, Aluva, Muvattupuzha, Kumarakom, Chengannur and Thiruvananthapuram.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | It was commonly referred to as the "Great flood of 99" as it had happened in the 'Kolla varsham' (Malayalam calendar) 1099.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | As per records, Kerala, which was administratively fragmented into three princely states (Travancore, Cochin and Malabar) during the time, had received excessive rains.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Just as now, all rivers were in spate and Periyar had flooded following the opening of the sluice gates of the Mullaperiyar Dam.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Freedom fighter, K Ayyappan Pillai has vivid memories about the "Maha pralayam", the great flood of '99.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "I was a school student when the heavy rains and floods submerged various places causing massive devastation. Normal life was crippled in the unabated rain," the 104-year old Ayyappan Pillai told PTI here.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "Roads had turned into rivers... overflowing water bodies... paddy fields inundated ... people even sought refuge on hill tops in many parts," he said.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi, who came to know about the deluge from the state's Congress leaders, had sent them a telegram on July 30, 1924 asking them to assist the relief measures of the government and also work in their own way to help the affected people.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In another telegram, the Mahatma said he was collecting money and clothes and his only thought was about people who had no food, clothes and shelter.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In an article in 'Navajivan' dated August 17, 1924, he said, "A sister has donated her four bracelets and a chain of pure gold. Another sister has given her heavy necklace. A child has parted with his gold trinket and a sister with her silver anklets."

| |

| − |

| |

| − | "One person has given two toe-rings. An Antyaja girl has offered voluntarily the ornaments worn on her feet. A young man has handed over his gold cufflinks. Rs 6994-13 anna-3 paise have been collected in cash up to date," Gandhiji said.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In the wake of the present floods, the state-based multi-lingual history website - dutchinkerala.com has carried Mahatma Gandhi's 1924 appeal to contribute to Kerala's relief fund to persuade people across the world to donate to the chief minister's distress relief fund.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Meanwhile, donations pouring into the Kerala chief minister's Distress Relief Fund (CMDRF) have crossed Rs 500 crore.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | From school children to corporate giants, all are contributing to the relief fund to help rebuild the flood-hit state, whose loss has been estimated to be over Rs 20,000 crore.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Gandhi in Delhi=

| |

| − | ==Harijan Sewak Sangh museum==

| |

| − | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016

| |

| − | [[File: Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi 1.jpg| Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi; Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File: Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi 2.jpg| Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi; Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File: Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi 3.jpg| Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi; Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File: Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi 4.jpg| Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi; Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File: Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi 5.jpg| Harijan Sewak Sangh museum, Delhi; Picture courtesy: [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Chapters-from-Gandhis-life-in-Delhi-fading-fast-17052016006013 ''The Times of India''], May 17 2016|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Richi Verma

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A treasure trove of memorabilia from the times the Father of the Nation frequented the campus with his wife, Kasturba, lies in utter neglect

| |

| − |

| |

| − | In a decaying hall in north Delhi's Kingsway Camp, the only surviving docu ment of the Poona Pact, a 1932 agreement between Mahatma Gandhi and Dr BR Ambedkar on legislatives seats for Dalits, lies under lock and key . It is among the rarest of rare items of Indian history . Yet it is not on display and lies locked away in a decrepit cupboard. That's best perhaps, because many other historic documents, mounted behind a smudged glass case, are almost falling to pieces.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | A look around the airy , redcarpeted hall at the Harijan Sewak Sangh would give archivists a shiver. There are no indications that historical artefacts in that room have even the basic protection given by humidity controllers or acidfree mounting for the precious photographs. In fact, the white paint on the walls are peeling to show a bluish undercoat, there are ugly seepage stains on the ceiling and ageing doors and windows allow the elements -heat, wind, rain, cold -to enter.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | And yet in this unique museum, rarely visited by anyone, there is a treasure trove of Gandhi memorabilia, including a steel plate and bowl that the Father of the Nation used during his frequent visits to the campus in the company of his wife, Kasturba. The three children of Gandhi's son Devdas were born in this ashram. The Harijan Sewak Sangh still has a boastful number of rare photographs, including one showing Gandhi nursing a leprosy-afflicted elder, as well as letters written by Gandhi, but all are in decrepit condition, brittle and falling to pieces.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | When TOI visited the place, it found this repository a vic tim of official apathy with a handful of people trying to keep a legacy alive against the greatest odds. A dusty glass case displays letters written by Gandhi, the handwriting faded, the paper yellowed, but his signature still intact. “We have the original Poona Pact signed by Babasaheb Ambedkar and Ma hatma Gandhi signed on September 24, 1932 in Yerwada Central Jail,“ said an official.But this document, probably the only one in existence, and some personal objects owned by Gandhi and his wife are locked in a cupboard and seldom accessed by scholars.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The 21-acre ashram, museum and library are managed by the Harijan Sewak Sangh, an independent non-profit organisation. It was formed in the wake of Gandhi's fast at Yerwada Jail that resulted in the Poona Pact. “Gandhiji opposed the segregation of what was then called the Depressed classes of the Hindu community into a separate electoral group. He saw in it a sinister device of the British government to create a split in the Hindu community in furtherance of its policy of `divide and rule','' reads a backgrounder at the ashram.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Officials said that after Gandhi's death, all his personal belongings were sent to the Nehru Memorial Museum, but most were returned to the Harijan Sewak Trust. The organisation's officials told TOI that they had neither the funds nor the resources to maintain the museum. “It would be our pride and joy if people came to see our Gandhi collection, but lack of funds limits our ability to maintain the museum,“ said Hira Paul Gangnegi, secretary of the trust.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Taking government help was contemplated some time ago, but the organisation's management felt the body would lose its independence.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | “We plan to approach the state tourism department in a few months because we want visitors to come to the ashram. Among other things, we have a Kasturba memorial exhibition as well as the foundation stone of a deityless temple that Gandhiji laid.'' Gandhi's value may not have as much importance in today's economy oriented politics. But there is a past that India has to conserve. Yet that is exactly what is on the endangered list at Harijan Sewak Trust.Gandhi's value may not have as much importance in today's economy oriented politics. But there is a past that India has to conserve. Yet that is exactly what is on the endangered list at Harijan Sewak Trust.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Gandhi in Malaysia=

| |

| − | ==The Mahatma Gandhi Kalasalai in Sungai Siput==

| |

| − | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F02&entity=Ar03103&sk=B61E4A2B&mode=text Aradhana Takhtani, This school in Malaysia reveres Mahatma every day, October 2, 2018: ''The Times of India'']

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[File: The Mahatma Gandhi Kalasalai was built by Indian immigrants in the 1950s when Malaysia was still under colonial rule.jpg|The Mahatma Gandhi Kalasalai was built by Indian immigrants in the 1950s when Malaysia was still under colonial rule <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F02&entity=Ar03103&sk=B61E4A2B&mode=text Aradhana Takhtani, This school in Malaysia reveres Mahatma every day, October 2, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Nothing in the nearly 3-hour drive through a vast expanse of lush fields and hills, from Kuala Lumpur to Sungai Siput, a small subdistrict of the royal town of Kuala Kangsar, prepares one for this. A simple but imposing Mahatma Gandhi statue ensconced in the reception cum prayer hall of a school has been greeting visitors since 1954.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The Mahatma Gandhi Kalasalai, as the Tamil school is called, is an edifying tribute to India’s Father of the Nation, in the Malayan Peninsula, by the founding father of Malaysian Independence, late V T Sambanthan.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The school reveals a rich history of the close ties between India and the British ruled Malaya in the 1950s; Mahatma Gandhi Kalasalai was inaugurated by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, who was at the time the first woman president of the UN General Assembly.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | “Three European plantation managers were shot dead by the communists in 1948, in Sungai Siput, and the town had become a hotbed of communist guerillas. Emergency was declared, and the then high commissioner of Malaya, Gerald Templer, was against this visit for safety reasons. However, Sambanthan convinced him that Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was the best leader to inaugurate a Gandhi school,” Sambanthan’s wife Uma recalls.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The decision to build a school and name it after Mahatma Gandhi was taken in 1951 but there was no state fund available. The school was shaped up, brick by brick, with passion and dedication of the town’s Indian community.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | While immigrants A Veeraswamy and A M S Suppiah Pillay, who had left the shores of India in the latter part of the 19th century, cleared their coconut plantation estate to donate 2 acres of land for the school, it was left to Veeraswamy’s son Sambanthan and Pillay’s son Periaswamy to plunge into the task of arranging funds. They donated $25,000 each for building classrooms, and engaged the famous Danish architect B M Iversen. Responding to the call of educating and liberating the poor plantation workers’ children, the labourers too responded with a total donation of $7000.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | The then British district officer of Kuala Kangsar, M J Mackenzie Smith, called it the result of private enterprise and personal sacrifice of the Indians. Today, the school is home to around 600 students, with every first minutes of the morning spent in remembering Gandhi, the great educationist.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | =Vignettes=

| |

| − | ==The goldsmith and the dacoits==

| |

| − | [[File: Bapu Katha- The goldsmith and the dacoits.jpg|Bapu Katha: The goldsmith and the dacoits <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL/2019/09/28&entity=Ar01000&sk=4B374A3B&mode=text Vaibhav Purandare, Sep 28, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | '''See graphic''':

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''Bapu Katha: The goldsmith and the dacoits''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==His preference to dictate==

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ''' One day, 56 letters '''

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Gandhi preferred writing to dictating. One day, I actually counted 56 letters that he had written in his own hand. Each one of these he re-read from the date line to the final detail of the address before handing them for dispatch. At the end of it he was so exhausted that pressing his throbbing temples between his two hands he lay himself down on the hard floor just where he was sitting

| |

| − |

| |

| − | (From Pyarelal Nayyar’s ‘Gandhi As I Saw Him’)

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[Category:Biography|GMAHATMA GANDHI

| |

| − | MAHATMA GANDHI]]

| |

| − | [[Category:India|GMAHATMA GANDHI

| |

| − | MAHATMA GANDHI]]

| |

| | | | |

| | =See also= | | =See also= |

| − | [[Mahatma Gandhi]] | + | [[Mahatma Gandhi]] |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[Mahatma Gandhi: ideology]]

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[Mahatma Gandhi: In South Africa ]]

| + | |

| − | | + | |

| − | [[Mahatma Gandhi: Assassination of]]

| + | |

| | | | |

| − | [[Mridula Gandhi]] | + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|C CHAMPARAN |

| | + | CHAMPARAN]] |

| | + | [[Category:History|C CHAMPARAN |

| | + | CHAMPARAN]] |

| | + | [[Category:India|C CHAMPARAN |

| | + | CHAMPARAN]] |

| | + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|CHAMPARAN |

| | + | CHAMPARAN]] |

| | + | [[Category:Places|C CHAMPARAN |

| | + | CHAMPARAN]] |

The Champaran struggle is a very good example of a restrained moral struggle combined with social responsibility, says Salil Mishra, who teaches history at Dr B R Ambedkar University .

“It shows how to mobilize opinion and support for a cause without resorting to moral hysteria,“ he says.

Sandeep Bhardwaj of Centre for Policy Research points out that there were no marches or strikes in Champaran. “Instead of defeating the opposition, Gandhi sought to win it over through the art of political persuasion. In contrast, the tendency in today's politics is often to burn down the house to light a candle achieve a political victory by any means necessary , even if it comes at the cost of larger communal harmony ,“ says Bhardwaj, who blogs at revisitingindia.com That's why , says social scientist Ashis Nandy , Gandhi's methods remain relevant. “There is an ethical component in his actions which has tremendous power and validity ,“ he says.

Indigo was an important crop for European planters in India. The conditions under which the peasants worked were oppressive. In his book, Gandhi in Champa ran, D G Tendulkar quotes a former magistrate of Faridpur, Mr E De-Latour of the Bengal Civil Service saying, “Not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood.“

Dinabandhu Mitra's play , Nil Darpan (1860), highlights the anguish of the peasant tenants (ryots).

“The story of Champaran begins in the early 19th century,“ writes Mridula Mukherjee in `India's struggle for Independence', “when European planters had involved the cultivators in agree ments that forced them to cultivate indigo on 320th of their holdings (known as the tinkathia system).“

The peasants had to pay enhanced rents over a period (sarahbeshi) or simply get out of the system paying a lump sum (tawan).

Gandhi arrived by train at Motihari in Bihar's Champaran district on April 15, 1917. He had come to the region following the request of Raj Kumar Shukla, a local cultivator. The next day, he was asked to leave.He refused, was taken into custody and summoned to court on April 18.

When Gandhi pleaded guilty, the colonial government was nonplussed. Unwilling to make him a martyr, authorities decided to withdraw the case and let him continue to gather statements of cultivators. On April 21, the case was withdrawn.

“Armed with evidence collected from 8,000 peasants, he had little difficulty in convincing the Commission that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and that the peasants should be compensated for the illegal enhancement of their dues,“ writes Mukherjee.

Misra points out that Champaran was the first systematic effort to introduce the peasant question into the nationalist politics.

“Till then the two had proceeded apart from each other.Nationalist politics was almost `peasant neutral' and peasant protests were local and spontaneous. Gandhi, who was an outsider to Champaran, introduced satyagraha and organised politics in the rural areas. He thus combined the rural with the national,“ he says.

“It was also at Champaran that Gandhi applied his techniques of satyagraha (perfected in South Africa) in India for the first time.Champaran should be seen as the first political laboratory in India where Gandhi made his experiments in satyagraha and then replicated them in other places (polite but firm defiance of the authority , basing struggles not simply on emotions and grievances but concrete enquiry and fact-finding, among others),“ he says.

And as Mahatma Gandhi himself wrote in his autobiography , “The Champaran struggle was a proof of the fact that disinterested service of the people in any sphere ultimately helps the country politically .“

Once a proud mansion, Belwa Kothi now wears the sadness of a ruin. The roof has surrendered to time, and the plaster is peeling. Close at hand lies a crumbling factory overrun by wild grass, forsaken like a stale idea.

But for this sleepy village in Bihar’s East Champaran district, these two buildings are reminders of its tryst with history. In the early 20th century, the factory was managed by a British officer AC Ammon and extracted neel (indigo), which farmers of the region were forced to cultivate on 15% of their land.

The oppressive system, known as tinkathia, was widely despised. Raj Kumar Shukla, a local farmer, drew Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s attention towards the exploitative system. Gandhi arrived in Bihar in April 1917, and Champaran became his first karmabhoomi in India. A worried Bettiah BDO wrote that Gandhi was “daily transfiguring the imaginations of masses of ignorant men with visions of an early millennium.” During those days of struggle, Gandhi had stayed for a night in Belwa.

While in Champaran, Gandhi shuffled between the district’s two main towns, Motihari and Bettiah. He travelled across the hinterland, recording statements of 8,000 cultivators. He convinced the Commission of Inquiry set up by the government that the tinkathia system needed to be abolished and ensured that the planters refunded 25% of the amount they had taken illegally from farmers.

That was then. Now, Belwa lives on memories, and rues unfulfilled promises. Shukla’s grandson, Mani Bhushan Roy, who still lives in his grandfather’s ancestral village, is skeptical about what has been achieved post-Independence. “We have electric poles, but no electricity. And we have roads that flood during monsoons,” he says. He keeps Shukla’s red hard-bound pocket diary in a black polythene bag and opens it sometimes to remind government officials of the role his grandfather played in the freedom struggle.

To celebrate 100 years of that landmark moment in the national movement, busts of Gandhi and Kasturba were installed in Belwa by Bihar’s minister of rural development Shrawan Kumar in 2018. Just a few months later, Gandhi’s statue was beheaded by anonymous miscreants. “We have written to the administration several times after that, but no action has been taken to restore it,” a Belwa resident says.

Many places associated with the Champaran struggle are also gone. At the house of Gorakh Prasad in Motihari, Gandhi stayed and compiled farmers’ testimonies. The house, which served as Gandhi’s base, was razed to construct a new house.

The residence of another freedom fighter, Ram Babu Kedia, who hosted Gandhi on various occasions, has been converted into a school though the students remain unaware of its history. “We have heard our grandfathers say that Gandhiji stayed in this building. But these are private properties now, and the owners can use them as they see fit. These buildings could have been preserved only by the government, but no attention has been paid to them,” a teacher at Shikshayatan School said.