Delhi/ New Delhi: A history, Dec. 1911- Aug. 1947

The Telegraph, India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

1911- 12: India’s capital shifts from Calcutta to Delhi

Tom Wright on the historical background

Tom Wright| Why Delhi? The Move From Calcutta | Nov 11, 2011| The Wall Street Journal blog

[In 1911], Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India, laid out in a letter why Britain should move the capital of its empire to Delhi from Calcutta.

In a letter to the Earl of Crewe, Secretary of State for India, sent from Shimla to London on Aug. 25, 1911, Hardinge pointed out that it has “long been recognized to be a serious anomaly” that the British governed India from Calcutta, located on the eastern extremity of its Indian possessions.

Photo: Prem Singh

The Telegraph, India

He then turned to more pressing reasons to move away from Calcutta, which for 150 years had served as Britain’s capital in India. For one, the Indian Councils Act of 1909, legislation passed by Britain’s parliament known as the Morley-Minto reforms, had allowed Indians for the first time to stand for legislative council positions.

For years the British had ruled by fiat from Calcutta, the commercial hub of India which the East India Company, in the eighteenth century, had developed from a small fishing village. Now, Hardinge argued that the rising importance of elected legislative bodies meant that Britain needed to find a more centrally located capital.

But Hardinge’s subsequent point to Crewe explains why the British were in such a rush to get out of Calcutta. The viceroy alluded to burgeoning opposition to British rule in Calcutta that was making it less than a hospitable home.

Britain had faced a rising tide of calls to extend a measure of self-rule to India since the late nineteenth century. That movement became most violent in Calcutta, the commercial and literary center of the country. In 1905, the British had cleaved Bengal, a massive and powerful province centered on Calcutta, in to two portions in an attempt to weaken this opposition to their rule.

The decision only inflamed nationalist sentiment, leading to a call for a boycott of British goods and, eventually, bombings and political assassinations in Calcutta.

According to Rudrangshu Mukherjee in the book, New Delhi, Making of a Capital, the idea of moving to Delhi was first mooted in June 1911 by Sir John Jenkins, a senior member of the government of India, as part of a plan to assuage these nationalist forces. The other part of the Jenkins’s proposal was to reunite Bengal, with redrawn boundaries.

The plan won approval from senior British officials and King George V, who only six months later during his visit to India, the first by a British monarch, announced the reunification of Bengal and the immediate move of the capital to Delhi.

The announcement, which King George made at an Imperial “durbar” – a gathering of Indian princes – in Delhi was a closely guarded secret. It was acclaimed by those in Delhi but met with hostility from many other quarters, especially in Calcutta.

For one, Delhi, an ancient city which had been the capital of Mughal India, was not yet set-up to accommodate the British, critics said. It would take twenty years for the architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker to complete “New Delhi,” a zone of grand avenues, stately buildings and whitewashed bungalows on the southern extremities of what now is known today as “Old Delhi,” the original Mughal city.

Lord Curzon, a former viceroy who had taken the decision to partition Bengal, was among the loudest naysayers. In a speech to the House of Lords, Curzon singled out why the government was rushing. “They desire to escape the somewhat heated atmosphere of Bengal,” he told the assembled grandees.

Hardinge had championed Delhi for its geographical position in the center of northern India and its links with the Mughal empire and Hindu “sacred legends.”

Curzon retorted that Delhi, in his view, was far from other important centers of British India, including Madras and Rangoon. And he pointed out the Mughals, long resident in Agra, had only made Delhi the capital “in the expiring years of their regime.”

British traders, largely located in Calcutta, a trading and jute processing center, also were furious over the secrecy. “The commercial classes view with apprehension the removal of the Government from all contact with mercantile and manufacturing interests,” a correspondent for The Times newspaper said in a report on Dec. 28, 1911. Curzon echoed this, claiming the government would live “shut off…from the rest of India.”

Mr. Mukherjee, the author and historian of Delhi, said in an email that Curzon, while viceroy, had seen Delhi as a place to “confer honors and baubles” to India’s princes. In 1903 he had organized an extravagant durbar in Delhi.

But Curzon, and other imperialists, also had tried to build up an “independent imperial heritage and tradition of the British Empire,” Mr. Mukherjee said. That was why Curzon had ordered the building of an imposing memorial to the late Queen Victoria in Calcutta, a city which the British had created.

In the end, the Victoria Memorial was only inaugurated in 1921, a full decade after Calcutta had ceased to be the capital of British India. The British bureaucrats, meanwhile, were living cramped in temporary quarters in Delhi’s Civil Lines district, waiting for the completion of the new administrative capital – but far away from the troubles in Bengal.

World War I had imposed severe cost restrictions on – and a new round of British opposition to – the construction of New Delhi. By this point, though, it was too late to change course. The new city was formally inaugurated in 1931. Within sixteen years British rule in India came to an end and India’s political class moved in to what is still today a bureaucratic city, aloof from much of India.

As for Calcutta, it remained an important trading and industrial center after 1911. But then in 1947, following the Partition of British India, which turned over parts of Bengal to the new country of Pakistan, the city began a precipitous decline. Cut off from its supplies of raw materials like jute, which were located in what was now Pakistan, Calcutta’s processing industries suffered. The city, in short order, became synonymous with poverty.

You can follow Mr. Wright on Twitter @TomWrightAsia. Follow India Real Time on Twitter @indiarealtime.

Additional details

February 13, 2022: The Times of India

From: February 13, 2022: The Times of India

From: February 13, 2022: The Times of India

To be sure, Delhi has a long history – it has been around for centuries (some say it dates back to 3000 BCE) – but it has been the capital of India for less than 100 years. So, what led to Delhi being chosen as the power centre of undivided India? Here’s some history.

Shifting from Calcutta to Delhi

The British ruled India out of Calcutta, a city they had occupied in various forms since the late 1600s. Calcutta worked for the British as long as they were in India as the East India Company, which needed a coastal city with a port as a trading hub. But once the British Crown took India over, ruling India from an eastern corner did not make sense.

Which is why, over 100 years ago, the then Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, sent a letter to the Earl of Crewe, secretary of state for India, saying that the empire should move its capital to the more central Delhi. Hardinge argued that the rising importance of elected legislative bodies required Britain to find a more centrally located capital.

Hardinge’s argument made sense to the British, and on December 12, 1911, the foundation of the new capital was laid in the presence of King George V at the grand New Delhi durbar. Other reasons for the move

Nationalistic sentiments had been growing in the late 19th century in Calcutta, which then was the literary and commercial centre of the country. The British adopted the infamous ‘divide and rule’ policy, and on October 16, 1905, sliced the state into two — Muslim eastern areas and Hindu western areas. This division inflamed nationalist sentiments and led to a call for the boycott of foreign goods, bombings and political assassinations. The pushback was strong enough for the British to reunite Bengal. But Calcutta was no longer the friendly city it once was, so the British realised they would be better off elsewhere. They believed Delhi would be more hospitable as well as more convenient.

Why Delhi?

For one, Delhi was more central to the empire than Calcutta. For another, Delhi had a history of being a capital city. It was the capital for the Mughals, who called it Shahajanabad (what is now Old Delhi). Between 3000 BCE and the 17th century, Delhi was supposed to be the site for a total of seven different cities. But what worked for the Mughals, and others before them, was simply too small for the sprawling British bureaucracy.

Once King George V approved the idea and laid the foundation for the new capital, British architects Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Herbert Baker were given charge of redesigning the new capital.

Long delays, and a world war

The foundation of New Delhi was laid in 1911, but the actual inauguration of the city as the capital took place only in February 1931. Of course building a city is not something that can take place overnight, but 20 years seems a long time. So why was there such a delay?

World War I, which began three years after the foundation of New Delhi was laid, imposed stringent funding constraints and this affected the construction of the capital of British India. Construction started after the war, and 'New Delhi' could only be completed and inaugurated in 1931.

Barun De on the consequences of the shift

Barun De | Capital shift | 2011| The Telegraph, India

The capital of British India was transferred from Calcutta to Delhi on December 12, [1911] a hundred years ago. Barun De on its far-reaching consequences

A hundred years ago three events took place which portended considerable change in the cultural life of Calcutta’s population, plebeian as well as patrician. The first was something whose reverberation was still loud when I used to go to the football fields on the Calcutta Maidan 60 years ago — the defeat of the British Army’s crack East Yorks regiment in the IFA shield by Mohun Bagan’s north Calcutta boys led by the Bhaduri brothers and others. This led to the culmination of patriotic fervour at the humbling of the gora herrenvolk by their Bengali subaltern havildars.

But the second and third events led to opposite sentiments. The Partition of Bengal was indeed rescinded, but the shine was taken off what might have been a famous victory for Bengali patriotism, since Bihar and Orissa and Assam were prised away from the old presidency, and only a truncated Bengali-speaking province, minus Manbhum (Purulia only after 1956) but with the Darjeeling hills subdivisions with their hill population who were not Bengalis and had earlier been in the Bhagalpur division, was set up as a residual province for the next 36 years.

And, to add insult to injury, the refractory Bengalis who had opposed the presidency’s partition with logic, songs and also bombs, were taught a stern lesson by the new King Emperor and his Consort’s visit to Delhi, the seat of his father’s durbar in 1877. The capital of British India, of its vast clerical population and of the seats of imperial power from Esplanade to Council House Street and all around Government House was summarily shifted to a city ruined several times in the last two centuries, from its sack by Persians and Afghans in 1739 and 1761, its desecration by Rohillas and Marathas in the rest of the 18th century, and the systematic destruction of the entire old city around the Red Fort by British avengers of the 1857 revolt.

The transfer of capital was a trauma in Bengali consciousness for the next generation, and was only catharsised, or perhaps just occluded, when the entire Ganga Padma Brahmaputra delta was cut away from the new province with Dhaka as its capital. This bare statement hides much of the reasons for what used to be called one generation ago the failure of nerve among the Bengali bhadralok. This was essentially a gentlemanly capitalist class used to living off the rents of ancestral land and property "without having touched the plough for seven generations" and averse to modern ideas about the dignity of labour, ideas which were becoming common among the professional classes in the Punjab, Maharashtra, and south west India. The spurt of small-scale consumer industry which had been initiated by swadeshi enterprise following the US and Japanese models, petered out when the sons of entrepreneurs expended their corpus in aesthetics, wine and the Calcutta Racecourse.

The agrarian labour, in a commercialised land system, dependent on paddy, jute and tea plantations, were immiserised by the failure of the managing agency system of Clive Street or Chowringhee to compete creatively with the industrial management that was already flourishing in Bombay, and had begun to grow in New Delhi and elsewhere.

The ethnic tensions and industrial strife connected with Marwari takeover of Scots and English business houses, and with the new forms of gutting the capital and denying labour the profits of the sickening industries in the conurbation from Metiabruz to Sahaganj has sometimes been interpreted as a direct consequence of imperial vengeful policy in 1911.

Yet there is an aspect of this policy which may perhaps have been turned to better effect had the bhadralok also been less contemptuous of some of their country people. Hindu Muslim rivalries for jobs, prestige and social position in the countryside had not been a major issue in the second half of the 19th century. The policies of Andrew Fraser and Bampfylde Fuller turned Curzon’s fiat into actual divide and rule. It has recently been argued that if the policy had been scotched after 1912 by Hindu as well as Muslim elements in the subordinate part of the ruling class in British Indian Bengal much of the ethno-religious tension, much of the parting of the ways between Sanskritised Bengali, and heavily Arabo-Persianised purba banglabhasha, much of the misunderstanding between Hindu landlords and predominantly Muslim and Scheduled Caste peasantry in the Dhaka-Rajshahi and Chittagong divisions, might have been scotched.

Had that happened, the Muslim League might not have gained the footing that World War II-time rulers of Delhi enabled it to foster in the lower Gangetic delta. After all the Pakistan demand originated in what a recent Pakistani politician has called geo-cultural as well as geo-political ‘Indusland.’ The movement for it gained ground only after the Bengal Congress not only of Subhas Chandra Bose but also Maulana Azad or the ‘Big Five’ turned their faces against coalition and understanding with AK Fazlul Huq and with the radical secularist elements of the Krishak Proja Party. The imperialist dismissal of Huq, the Bengal Famine, and British failure to rehabilitate either agriculture or industry after the war exacerbated the recent political tensions, led to the Killings in Calcutta and Noakhali in 1946, and to messianic fervour. A demand now grew among the Muslim masses for the mid-20th century version of ‘paribartan chai.’

But then 1911 was not just a tale of two cities, whether Calcutta v. Delhi or Dhaka v. Calcutta. The century that we are coming out of into the 21st,saw endemic violence, the ghosts of which cannot be laid to rest by taking sides. The Bengal that was divided at least three times through the century, has been divided only in politics and in recent constructions of religion. But it has a heart that beat together in 1971. Those feelings, I feel, still exist, and there are various possibilities by which the old geographical entity that was once a presidency and is today eastern south Asia can find ways and means for acting together.

The writer is Tagore National Fellow in Cultural Research, Victoria Memorial Hall, Calcutta

Shifting pain

Subhro Niyogi & Jaideep Mazumdar | TNN, The Times of India | Dec 11, 2011 | Shifting pain

Only a handful of people knew of the proposal to transfer the capital of the British empire in India from Calcutta to Delhi. The discussions and plans were kept top secret, as was the estimated cost of shifting bag and baggage - 4 million sterling. The speed and secrecy with which such a monumental decision was taken, stumped everyone.

Astonishing as it may seem a century later, the formal request to transfer British India's capital from Calcutta to Delhi was made just three and a half months before it was announced by King George V on December 12, 1911. The announcement at the Delhi Durbar came just 41 days after the British government formally agreed to the proposal.

In early 1911, an eight-member committee was constituted by the Governor General, Lord Hardinge of Penhurst, to look into the viability of Calcutta continuing as the capital of the British empire in India. The panel, which had only one Indian member in Saiyid Ali Imam, submitted its report on August 25, 1911, arguing strongly for shifting the capital to Delhi.

It set out a number of reasons in favour of the shift, but the crux was that Calcutta was the seat of a provincial government and the Government of India cannot have its seat in the same city. The prominence that Calcutta Presidency enjoyed as the seat of both Government of India and provincial government was a cause of envy to the other two Presidencies of Madras and Bombay.

Calcutta, the committee argued, is "ill-adapted" to be the capital of the "Indian Empire", which extended from Burma in the far East to Afghanistan in the west. It made particular mention of the partition of Bengal that had generated ill-feeling among Bengali Hindus.

"Public opinion in Calcutta is by no means always the same as... elsewhere in India," the panel said, adding that Delhi had "splendid communications", a good climate for seven months and being closer to Shimla (the summer capital) would result in substantial savings. The British were tired of Calcutta's heat and humidity. Besides, Delhi is closer to the commercial centres of Bombay and Karachi "whose interests are sometimes opposed to those of Calcutta", the panel noted.

It listed out several political advantages as well - Delhi's connection with Hindu legends, especially the Mahabharata war, and that "Mahomedans" would be happy to see the "ancient capital of the Moguls restored to its proud position as the seat of an Empire". Despite minor reservations, the Secretary of State for India agreed to the transfer of capital and said: "The ancient walls of Delhi enshrine an imperial tradition comparable with that of Constantinople or with that of Rome itself."

The committee also said that the "Hindi-speaking people of Behar", and the people of Orissa and Chhota Nagpur have "nothing in common with Bengalis" and had been "unequally yoked with the Bengalis". Therefore, all these three regions should have separate Lieutenant Governors.

The Secretary of State said that Calcutta would always be a "Bengali city in the fullest sense" and hence unsuitable to be the capital of British India. "History teaches is that it is sometimes necessary to ignore local sentiment or to override racial prejudice in the interest of sound administration or in order to establish an ethical or political principle," he noted.

The panel was aware that the only serious opposition would come from the European commercial community of Calcutta. Bengali Hindus would also not be happy, it said, but noted that "their opposition would raise no echo in the rest of India" and this community "could be placated by upgrading the Lieutenant Governorship of the province to that of a full Governorship".

Another key reason was the "undesirable" possibility of the Governor General of India and the Governor of Bengal residing in the same city and "liable to be brought in various ways into regrettable antagonism or rivalry".

The Secretary of State felt that if the transfer is to be approved, "it is imperative to avoid delay". "I cannot recall in history... a series of administrative changes of so wide a scope, culminating in the transfer of the main seat of government carried out with so little detriment to any class of the community, while satisfying the historical sense of millions, aiding the general work of government and removing the deeply felt grievance of many," he noted.

Stating this, he gave his general sanction and agreed that the transfer of the capital would be a worthy subject for the announcement by King-Emperor in person at the Delhi Durbar.

And that was that. King Gorge V put the seal on the proposal by announcing the capital shift on December 12, 2011. And the entire country heard it in stunned silence.

New research has however revealed unknown facts about the transfer. Debasish Basu, a doctor by profession and a passionate researcher on Kolkata, does not believe such a huge decision could have been settled in exchange of just one dispatch between the Governor General in India and the Secretary of State for India in London. He is certain there were several closed-door meetings for quite some time to draw up the strategy for the capital shift before it was announced.

"I believe it started in 1906, after the partition of Bengal, and took time to evolve. People didn't get to know about it because it was kept a closely-guarded secret lest a tip-off derails the proposal," said Basu, pointing to how something as innocuous as setting up the Fever Hospital at the Medical College had led to intense discussion and debate that were recorded in voluminous documents.

Basu pointed out that the Europeans, with huge trade interests in Calcutta, would have raised objections. "Furthermore, the bureaucracy was mostly Bengali. Such a policy-making decision that would go against the Bengalis would have run into trouble. It is the same as the Teesta water accord that the Manmohan Singh government at Centre kept secret from Mamata, fearing it would be scuttled. Finally, that is what happened. There were many Bengalis like Sir Prabhash Chandra Mitra who were members in the Governor General Council. They would have opposed the move till it was scuttled. Hence, secrecy was important," he reasoned.

The decision to get the King to announce the shifting of Capital was an extremely shrewd one as it instantly became a binding order. "Europeans would not speak against the King's word. Bengalis were yet to become rebellious enough to challenge a King's proclamation either. The British knew that once King George V announced it, citizens would realize and accept that a decision had already been taken," said Basu.

1931: New Delhi is inaugurated, becomes national capital

HIGHLIGHTS

The British government believed that ruling India from Delhi was easier and more convenient than from Calcutta.

Four million British pounds was the cost of shifting the entire administration from Calcutta to Delhi.

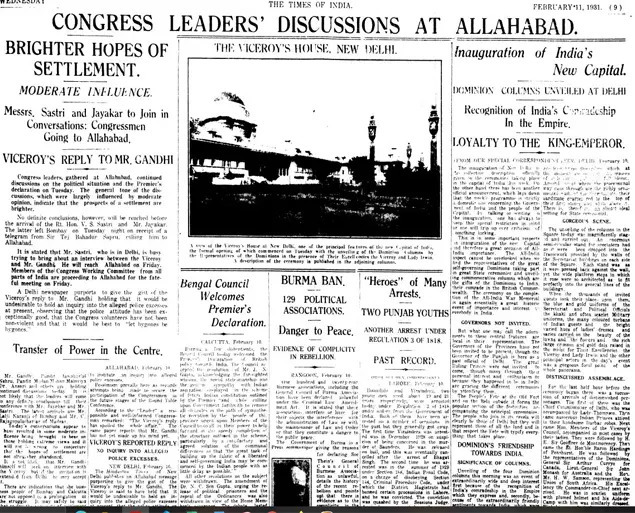

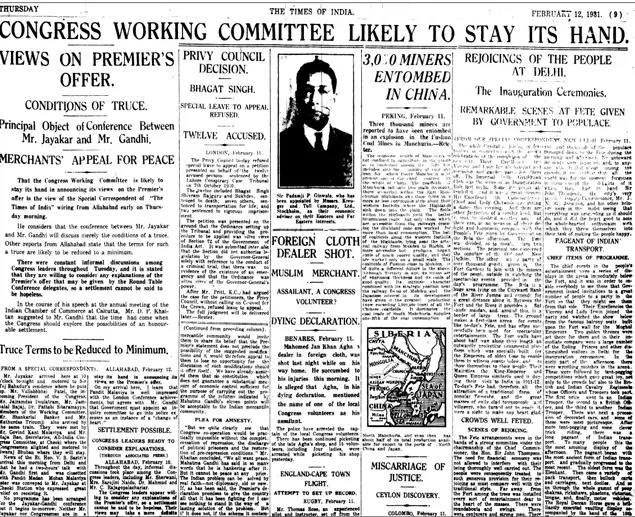

NEW DELHI: It was on February 13 , 1931 that New Delhi became the power capital of undivided India, ending a wait of 20 years.

The foundation of the new capital was laid On December 12, 1911 by King George V during New Delhi durbar (a pompous royal ceremony).

However, it was 20 years later that King George V, during his visit to India, announced that New Delhi will replace Kolkata (then Calcutta) as national capital.

And finally, on February 13, 1931 Lord Irwin inaugurated the new capital - New Delhi.

But why!

Some 100 years ago, then Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, said in a letter why the Great Britain should move its empire capital from Calcutta to Delhi.

The letter was sent from Shimla to London on August 25, 1911 and addressed to the Earl of Crewe, Secretary of State for India. Hardinge highlighted the anomaly that the British governed India from Calcutta, an eastern extremity of its Indian properties. Hardinge argued that the rising importance of elected legislative bodies required Britain to find a more centrally located capital.

Partition of Bengal

Calcutta was the literary and the commercial centre of the country. But on October 16, 1905, the British sliced the state into two - Muslim eastern areas and Hindu western areas. The partition, aimed at taking control of the state, under 'divide and rule' policy inflamed nationalist sentiments and lead to a call to boycott all foreign goods. Eventually, bombings and political assassinations took place in Calcutta.

Since Calcutta had now become less than a hospitable place for them, the British were in a rush to leave the city.

Hardinge's plan was approved by the first British monarch, King George V who announced the reunification of Bengal and decided to immediately move the Capital.

20 years!

Shahajanabad (old Delhi) no doubt had been the capital during the Mughal era but it wasn't equipped enough to accommodate the British. As such British architects, Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Herbert Baker took the charge of redesigning the new capital.

The new capital was carved out from undivided Punjab province and was named 'New Delhi' in 1927.

Initially, everyone was hoping that the new capital would be ready within four years. But unavoidable events like World War I delayed the process to over 20 years. The war, which imposed stringent funding constraints, affected the construction of the capital of British India.

As they say, swift as an arrow, the British set up a temporary seat of government in Civil Lines. And in 1912, constructed a secretariat building to house government offices while the North and South Blocks were constructed on Raisina Hill in New Delhi.

However, for Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker it took another 20 years to complete 'New Delhi' before it could be inaugurated as the capital of undivided India in 1931.

Some more reasons

- One of the reasons for declaring it the capital was that Delhi was the financial and political centre of many empires that had earlier ruled India.

- Another main reason for the capital shift was the location of Delhi. Calcutta was situated in the eastern coastal part of the country, while Delhi was located in the northern part.

- The British government also believed that ruling India from Delhi was easier and more convenient than from Calcutta.

- The announcement was followed by the foundation stone for Coronation Park, Kingsway Camp, which was also the Viceroy's residence.

- Four million British pounds was the cost of shifting the entire administration from Calcutta to Delhi.

- It has been well known that between 3000 BC and the 17th century AD, Delhi was supposed to be the site for a total of seven different cities.

- There were a total of 14 walled gates that protected the city in the beginning. Five of them, including Ajmeri Gate, Lahori Gate, Kashmiri Gate, Delhi Gate, and Turkman Gate are still standing.

Connaught Place was designed as a part of Lutyens Delhi, and is one landmark that defines the capital even after all these decades. This picture was taken when the then Premier of the Soviet Union, Nikolai Bulganin visited India in 1955.

This was Chandni Chowk before all the illegal encroachments made the place an eye sore.

Today, our President travels in snazzy cars. But nothing can beat the classiness of a cavalcade of horse drawn carriages. Here's our first President Dr. Rajendra Prasad in 1950.

See also

Delhi: the Battle of Delhi, 1803

Delhi/ New Delhi: A history, Dec. 1911- Aug. 1947