Delhi: History (730- 1911)

Contents |

Delhi: History (730-1877) by H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I

This section was written between 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

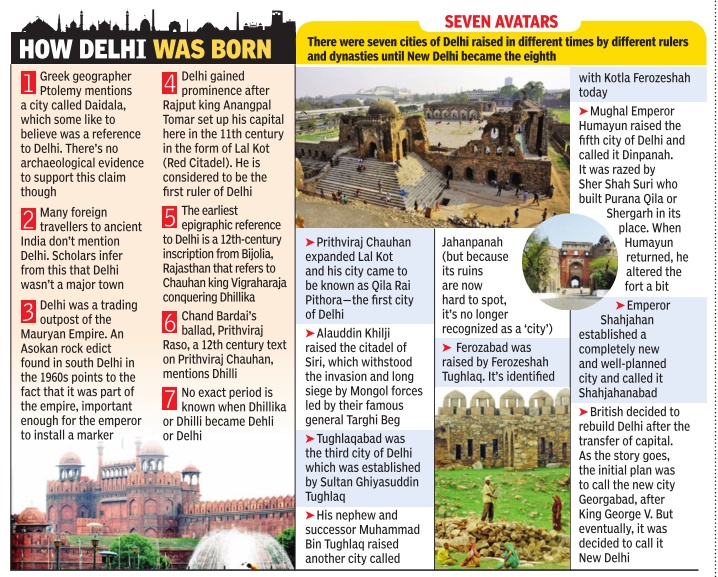

ASI archaeologist BR Mani says, “The Killi-Dhilli Katha mentioned by a number of authorities becomes very relevant.” He was referring to a section of the 12th century epic poem ‘Prithviraj Raso,’ a tale of how Delhi got its name. He added, “The truth is Anangapala II established the city and wanted to uproot the iron pillar, which was supposed to be the nail of the earth. Scholars warned him against that. It was colloquially called Killi, and then came to be known as Dhili. That, later, became Dhillika or Dhillikapuri.” (TOI)

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE KINGS OF DELHI, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO

THEIR CONNECTION WITH THAT PLACE, TO WHICH IS ADDED AN

HISTORICAL TABLE OF THE MOGHAL RULE.

THE early history of Delhi is fairly summarised in the words of the popular distich :—

“Pahle Dilli Tuwar, piche Chauhan,

Aur pichle Moghal Pathan.” (“First the Tuwar held Delhi, then the Chauhan, and then the Pathan and Moghal.”) Of the Tuwars or Tunwars, only the Kings Anangpal the First and Second are specially connected with Delhi. The city is believed to have been originally colonised from Kanauj in the sixth century of our era, to which the Iron Pillar belongs, and was refounded by the former king in 730 A.D., and repeopled by the latter in 1052

To Anangpal I., and to a son of his, are ascribed the Arrangpur band and Suraj Kund (p. 292), and to his later successor, the Anang Tal, in the Lal Kot. A hundred years after the second refounding by the Tunwars, a king of that line was defeated by the Chauhans, and the last prince of this dynasty, the Prithvi Raja, known popularly as Rai Pithora, built or fortified the city now called by his name, and probably about 1180 A.D. constructed the Lal Kot as a defence against the Muhammadan mvaders from the north, who had recently reappeared in India under the famous Muhammadbin- Sam, known as Shahab-ud-din Ghori.

This Pathan chief had met with a severe defeat in 1191 A.D. at the hands of the Prithvi Raja on the banks of the Ghaggar, near Thanesar, then a very important city, which Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni had already captured 180 years previously; but returning two years later he crushed the Chauhan prince near the same place, the Indian chief falling in the battle, or perhaps being put to death after it.

Following up this victory, his general, Kutab-ud-din Aibak,1 captured Delhi, and later Ajmir and Kanauj. Soon afterwards Shahab-ud-din, who up to this date had been associated with a brother, became sole ruler of Ghor and Ghazni, and assumed the title of Abul Muzaffar Muiz-ud-din-Samt but was still generally known as Muhammadbin- Sam, by which designation he is mentioned in the Inscriptions on the Kutab Minar.[ 1 Aibak probably means Moon Lord, the latter syllable representing Beg.]

During the next years the Muhammadan conquest of India was extended as far as Gwalior, Kalinjar, and Benares; and in 1196 Kutab-ud-din visited his master in Ghazni, and on his return erected the great screen of arches in the Kuwat-ul-Islam Mosque. A revolt of the Ghakkars, due to the Sultan’s disastrous defeat in Kharizm and their invasion of the Lahore country, 2 called both master and lieutenant to that place, and on his way back from there to Ghazni, the king was slain in a night attack on his camp.[ 2 At the time that the Muhammadan Pathans were engaged in wresting India from the Hindus, Richard Coeur de Lion was engaged in trying to wrest the Holy Land from the Muhammadan Saracens.]

Thereupon Kutab-ud-din Aibak declared himself Ruler of India, and thus in 1206 A.D. founded the Muizzi Dynasty, so-called from the title of the king, known generally as the Slave Kings, three of the principal rulers among them having originally been Turki slaves. Four years later, during which period Muhammadan arms were extended to Bengal, the first emperor of India died from injuries caused by the pommel of his saddle upon a fall with his horse while playing polo at Lahore, and after a year’s interval was succeeded by Altamsh (1211-1236), who took the titles of Shams-ud-dun-ya-wa-ud-din Abul Muzaffar Altamsh.

This prince consolidated the Muhammadan power in India, and was acknowledged as an independent king by the Khalif of Bagdad, whereupon he called himself Násir-i-Amir-ul-Mumenín, or Ally of the Prince of the Faithful. Among his conquests special mention is made of that of Bhilsa, and of the famous Buddhist tope there.

He enlarged the great Kuwat-ul-lslam Mosque, completed the Kutab Minar, and built the tomb of his son, known as Sultan Ghári Altamsh was succeeded by his son Muizz-ud-din, who was shortly afterwards murdered by his brother Rukn-ud-din.

When the latter sought to seize his sister, the Princess Raziyah, whom her father had declared more fit to rule after him than any of his sons, she, according to Ibn Batuta, assumed the coloured dress of a suppliant prescribed by her father, and addressed the people from the palace terrace, upon which the troops deserted her brother, and brought him captive to her from the mosque, and she ordered him to be executed, saying, “The slayer must be slain.” For three years she maintained her position, but she was then defeated by the rebellious Turki Governor of Lahore, who compelled her to marry him, and was shortly afterwards murdered in her flight after a second defeat in a battle, by which her husband sought to replace her on the throne.

Her grave has been described at The chronicler of the time describes the Sultan Raziyah as follows

“She was wise, just, and generous, a benefactor of her kingdom, and dispenser of justice, the protector of her subjects, and a leader of her armies. She was endowed with all the qualities befitting a king, but she was not born of the right sex, and so, in the estimation of men, all these virtues were worthless. May God have mercy on her.”

Another brother, Nasir-ud-din, finally succeeded her, and reigned under the auspices of his minister and brother-in-law, Balban, for twenty years, during which the Moghals repeatedly invaded India. Chenghiz Khan had penetrated as far as the Indus in the reign of Altamsh, and the ambassador of Huluku Khan, who destroyed the Caliphate of Baghdad, and was perhaps the fiercest of all the scourges of God in Asia, was received in Delhi in 1259 A.D.

Nasir-ud-din was succeeded by his minister, the last of the great slave kings, who took the titles of Sultan Abul-Muzaffar - Gheias – ud – din - Balban, and reigned from 1265 to 1287. His original name was Ulugh Khan, and he was one of a leading band of the Shamsi slaves of Altamsh, known as the Forty.

His court was the refuge of many princes and learned men flying before the Moghal invaders, and it was his son, the Khan-i-Shahid who invited the Persian poet, Sádi, to India. Of him the chronicler of his time wrote:— “The dignity and authority of the Government were restored, and his stringent rules and resolute determination caused all men, high and low, throughout his dominions, to submit to his authority. He was inflexible in the administration of justice, showing no favour to his brethren, or children, or associates, or servants.”

He was succeeded by his grandson, Kaikubad, whose father, Bughra Khan, was practically king of Bengal, and the historians record a touching and dramatic meeting of the son with his father who refused to seek the Imperial dignity. Unhappily, Kaikubad gave himself up to evil courses, and after two years was murdered, whereupon the nobles elected an old and experienced General, Jelal-ud-din Khilji, as emperor, and the first Pathan dynasty in India succeeded to the line of Turks in 1290.

The latter were naturally opposed to his elevation, and he did not obtain possession of Old Delhi for some, time, during which he resided at Kilokhri, about two miles south of the Mausoleum of Humayun. The poet, Amir Khusrau, was one of his close friends, and the keeper of the Kuran.

His nephew and son-in-law, Ala-ud-din, while Governor of Karrah (then and long afterwards an important place, which was finally superseded by Allahahabad), penetrated further south Muhammadan arms had ever reached hitherto, and captured Deogir, now Daulatabad, then one of the greatest cities in the north of the Deccan. On his return to Karrah, mischief was made between him and the king, and in order to remove this, the latter proceeded to the governorship of his nephew.

The treachery and murder which were thereupon enacted are thus narrated :— “When he (Ala-ud-din) met the Sultan, he fell at his feet. The Sultan took his hand, and, treating him as a son, kissed his eyes and cheeks and stroked his beard, and said : ‘I have brought thee up from infancy.

Why art thou afraid of me ?’ At that moment the stony-hearted traitor gave the fatal signal, and Muhammad Salim of Samana—an evil man of an evil family—struck at the Sultan with a sword, but the blow fell short and wounded his own hand. He again struck and wounded the Sultan, who ran towards the river crying, ‘Ah thou villain, Ala-ud-din! What hast thou done ?’ Ikhtiyar-ud-din, who had run after the betrayed monarch, threw him down, and cut off his head, and bore it dripping with blood to Ala-ud-din. . . . The hell-hound, Salim, who struck the first blow, was, a year or two afterwards, eaten up by leprosy.

Ikhtiyar-ud-din, who cut off his head, very soon went mad, and in his dying ravings cried that Sultan Jelal-ud-din stood over him with a drawn sword, ready to cut off his head.” Parracide as he was, Ala-lid-din, who took the title of Sikandar Sani — the second Alexander —was a strong ruler,1 a great fighter, and, as has been seen a notable builder. [1 Among other acts of this prince was one which had a farreaching effect—the imposition of the religious polltax, or Jaziyah, upon all non-Muhammadans. This was removed by Akbar in the ninth year of his reign (1565 A.D.), but was re-enacted by Aurangzeb in 1680. It was finally repealed, at the request of Raja Jai Singh, by the Emperor Muhammad Shah.]

He conquered Guzerat, Chitor, and Malwa, while his general, Malik Kafur, invaded Telingana a second time, captured Warangal, and penetrated as far south as the Karnatic coast, and he defeated the Moghals in several pitched battles outside Delhi.

On the occasion of their invasion in 1299, under Kutlugh Khan, he fortified his camp at Siri, and this place afterwards became New Delhi, and was joined to Old Delhi by the defences of Jahanpanah The repulse of the Moghals on this occasion was due mainly to the extraordinary gallantry of a general of the king’s, named Zafar Khan, and according to the chroniclers, the Moghals for many years afterwards would say to their horses when they refused to drink: “Why are you afraid—do you see Zafar Khan?” Pyramids of the skulls of the slain Moghals used to be erected before the gates of the city.

Ala-ud-din died in 1315 of dropsy— “his days did not help him”—and it is recorded that his body was brought out of the Red Palace and buried in a tomb in front of the Jama Masjid Shortly afterwards Malik Kafur was murdered by unruly mercenaries, and when during the next four years repeated murders had practically extinguished the Khilji family, Ghias-ud-din Tughlak, Governor of the Punjab, and the bulwark of India, against the Moghals, moved on to Delhi, and, after gaining an easy victory was elected emperor, the nobles declaring, “All who are present here know no one besides thee who is worthy of royalty and fit to rule.”

This election re-introduced a Ruling House of mixed Turki blood. The Sultan devoted his energies principally to the construction of the city and citadel of Tughlakabad, possibly because he considered the widely extended position of the three cities of Delhi was not capable of defence against the Moghals, and on returning from an expedition to Bengal, in 1324, was murdered by his son, Juna Khan, subsequently Muhammad Shah, who contrived that a pavilion in which he was entertaining his father at Aghwanpur near Tilpat should fall upon him.

The story of his quarrel with Shekh Nizam-ud-dm Aulia has been narrated above Muhammad Shah Tughlak, who bore the title of Sultan Abul Mujahid Abul Fatah, is remembered chiefly for his attempts to regulate prices, and introduce a debased currency,2 for his cruelties, and for the insane persistence with which he sought to transfer the capital of India from Delhi to Deogir, which would inevitably have resulted in the Moghals assuming possession of the whole of the north of the continent.[ 2 It is on record that piles of his coinage tokens lay for many years among the ruins of Tughlakabad, and possibly excavation might yet lead to the discovery of some of them.]

The desolation produced in Old Delhi, a city “which for 170 or 180 years had grown in prosperity, and rivalled Baghdad and Cairo,” is thus described : “The city and its serais and suburbs and villagest spread over four or five kos, were all destroyed. So complete was the desolation that not a cat or a dog was left among the ruins.” A fearful famine completed the misery of the capital and many of the provinces, and the people and governors rose in rebellion on all sides.

While engaged in putting down one of these in Sind, and seeking to capture Thatta, the Sultan died in 1351, and his cousin, Firoz Shah, was forcibly placed on the throne, and proceeded with the army to Delhi, where he ruled till 1388, as Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlak.

The public works of his reign, and his joys and sorrows, have been already noticed He was, further, a great constructor of canals, gardens, and bands—the first canals in India were made by him for his palaces, and they still partially survive in the Western Jumna and Eastern Jumna canals—and he was a mighty hunter; he waged many campaigns, and lost his army and nearly lost his own life twice in the deserts between Sind and Guzerat.

Besides his own name, he had the name of nine of his predecessors, Muiz-ud-din-bin-Sam, Altamsh, Nasir-ud-din, Balban, Jelal-ud-din Khilji, Alaud- din, Kutab-ud-din, Gheias-ud-din Tughlak Shah, and Muhammad Shah, recited in the public prayers. Towards the end of his life he was apparently deposed by his son, Nasir-uddin, but he recovered his position before his death. “Since the days of Nasir-ud-din, son of Shams-ud-din Altamsh,” writes the author of the Tarikh-i-Mubarik Shah, “there has been no king in Delhi so just and merciful, so kind and religious, or such a builder.”

The same chronicle tells us that when the Sultan went out in state, “the slaves accompanied him in distinct corps; first the archers fully armed; next the swordsmen, thousands upon thousands, then the fighting men riding upon male buffaloes, and the slaves from Hazarah, mounted on Arab or Turki horses, bearing standards and axes,” a warlike state of things denoting very different conditions from those of the reign of Aurangzeb, noticed by Bernier

He was succeeded first by a grandson, the son of Fatah Khan who was killed soon afterwards, and ultimately, after much fighting, which extended to the very streets of Firozabad, by the son who had deposed him, and who shortly left the throne to a minor child, Mahmud Shah Tughlak. This was the Sultan who suffered utter defeat at the hands of Sultan Timur in 1398 For the time he fled to Mandu, Khizr Khan, Governor of the Punjab, being placed in power by Timur, as Shah Alam was by Ahmad Shah, nearly four centuries later; but he afterwards returned and ruled nominally till 1414, when Syad Khizr Khan, who had several times failed to drive him out, succeeded him, and founded the Syad dynasty.

This lasted till 1450, and was succeeded by the second pure Pathan dynasty, the Lodis, whose first chief reunited the Punjab to Delhi, and from whose last scion, Ibrahim Lodi,1 the Moghal Baber, won the empire of India at the battle of Panipat, on 21st April 1526.[ 1 When the dead body of this prince was brought before Baber, he raised the head and said: “Honour to your bravery.”] Nothing in the record of these two dynasties calls for mention in connection with Delhi, beyond the buildings which they erected, and which have been noticed in their place

The last Lodi princes resided at Agra, and here Baber, whose visit to Nlzam-ud-din and the Kutab has been noted and, for the most part, his son Humayun, dwelt. Sher Shah was too much engaged in fighting throughout his brief reign to reside long in his new city of Delhi His son and successor built the Salimgarh but his second son, Adil Shah, on whose behalf Hemu contested the empire with Bairam Khan at Panipat, removed again to Agra,

The previous battle of Sirhind was won against a revolted brother, Sikandar Shahh whom Bairam Khan and Akbar were endeavouring to intercept when the Emperor Humayun met with his death at Delhi.

The inception of the Purana Kila by this king, his death at that place, and his mausoleum to the south of it, are the principal events of Moghal rule connected with Delhi previous to the reign of Shahjahan. The interrex Sher Shah, and his successors in the third Pathan dynasty on the throne of India, were naturally attracted to Delhi in preference to Agra but the seat of power had been moved again to the southern capital when

Humayun returned in I556A.D., and Agra and Fatahpur Sikri were the capitals of Akbar (1556-1605), as Agra and Lahore were of Jahangir (1605-1627).

The principal events of the reigns of the five great Moghal emperors and their successors will be found in the tables at the end of this chapter, taken from the “Imperial Gazetteer of India,” edited by Sir W. W. Hunter. Modern Delhi, or Shahjahanabad, was founded in 1638 by the Emperor Shahjahan (1627- 1658), the palace being first built, then the walls of the city, and then the Jama Masjid; the materials needed were largely taken from the half-deserted cities of Firozabad and the Delhi of Sher Shah. Many of the works were no doubt still in progress when the emperor fell ill and was carried off to Agra by his eldest son, Dara Shekoh, and was there deposed by his youngest son, Aurangzeb, in 1658.

Bernier tells a pathetic story of how, in his captivity, the ex-emperor longed to see the last of his building creations once more, but indignantly refused to view them merely from a war vessel on the river, as stipulated by his successor.

A native chronicle, translated by Dr Hoey, C.S., states that the father forgave his son when on his deathbed, at the instance of two holy men who lived with him during his latter days. It may be recorded here to the credit of human nature that the Kazi of Delhi refused to recognise Aurangzeb as emperor, so long as his father should live, and was, in consequence, deposed from his post.

The title of Delhi Shahjahanabad, to be called an Imperial City, has been briefly noticed on The Emperor Aurangzeb resided at Delhi in the early years of his reign, and it was his court which was visited there by Bernier and Tavernier.

Much about the same time, viz. in the Annus Mirabilis of 1666, it was visited by one who was destined to be the real destroyer of the Moghal power, the great Mahratta Sivaji. One of the most mournful sights perhaps, which the Chandni Chauk ever saw, was, first, the parade of the living Prince Dara Shekoh after his capture, and the subsequent parade of his lifeless body after his murder. Upon the death of Aurangzeb at Ahmadnagar in 1707, and of his eldest son at Delhi, in 1712, the capital once more became the centre of Moghal interests, and was soon the scene of the dying throes of the empire, which really ceased to exist by the middle of the century

In their lifetimes the emperors after Aurangzeb were the creatures of some powerful minister— first Zulfikar Khan, the captor of Sivaji Fort of Rajgarh, then the Syad 1 brothers, then Ghazi-uddin, the elder, and so on, down to the time of the Mahrattas; and no one of them after that emperor, who was buried 2 by his own request in a simple grave at the Rozah near Daulatabad, attained, on his death, the honour of a mausoleum, while the resting-place, or the exact spot of the resting-place, of several, is not even known. [1 These belonged to the famous Barah family in the Muzaffarnagar district, which, from the time of Akbar, was noted for its bravery, and in the van of battle, a post which it always held, had done many notable deeds of valour.][ 2 The pathetic despairing letters which the Emperor wrote to his sons from his dying bed are well known. The chronicler records that “still in the dread hour of death the force of habit prevailed and the fingers of the dying King continued mechanically to tell the beads of the rosary they held.”]

Of those who reigned from 1712 to 1761 Jahandar Shah, Farukhsiyar and Alagmir II. came to violent deaths, while Ahmad Shah and Shah Alam II. were blinded, the former being also deposed.3 One only, Muhammad Shah (1718- 1748), the last to sit upon the Peacock Throne, reached his grave in peace (if an end can be called peaceful, which is ascribed to a broken heart caused by the loss of his minister, Kamar-uddin Khan, who had been killed at Sirhind, while he and Prince Ahmad were repelling the first invasion of Ahmad Shah Durani and his Pathans), and of him it is recorded that his coffin consisted of an old clock-case, found in the palace, and his pall of a tattered cloth obtained from the Zenanah.[ 3 This takes no notice of two young princes, Rafi-ud-daulah and Rafi-ud-darjat, both of whom died in 1717 A.D. The Emperor Farukhsiyar, it will be remembered, granted the first special firman to the East India Company in 1715, in gratitude for his cure by Surgeon Hamilton, who lies buried in the churchyard of the Old Cathedral at Calcutta. It was in his reign that the Sikh leader Banda was executed in Delhi, a deed which the Sikhs considered was finally avenged in September 1857.]

The massacre which took place at Delhi, upon the invasion of Nadir 4 Shah [4 In the hall at the back of the Chihal Situn Palace at Isfahan, is also a picture of the victory of Nadir 1 Shah over Muhammad Shah on 17th February 1739. As a work of art, it is unfortunately the worst of the whole series, but it probably gives a fairly correct representation of the costume and arms of the time.[ 1 Nadir Shah should be of some special interest to Englishmen, in that, like one of the Shogun Mayors of the Palace in Japan, he appointed a countryman of theirs to be his Fleet master, with a less successful result than in the case of his Eastern compeer.] The Delhi king advances placidly from the left, seated on a pad upon a white elephant without any driver; he wears a low crown, and has a closely clipped beard. On either side of the royal elephant are other dark ones, some with sword blades attached to their trunks, and others seizing Persians with their trunks. In the foreground march Indian matchlock men with shouldered arms, clad in saffron dresses. Behind the Delhi forces, and firing straight into them is the Moghal artillery.

On the right sick Nadir Shah, represented with a full dark beard, advances on a very sorry roan horse, clad in green over red, and with bracelets on his wrists and a mace in his right hand; on his head he wears a high curiously shaped cap, with indented sides and top, and most of his Kizilbash horsemen wear the same. In the foreground by him, and in the centre of the picture, are a number of slain men and some riderless horses, and among these stands an old white-headed man, intended perhaps for Saadat Ali Khan Nawab Wazir of Oudh, and Prime Minister of the Delhi King, who is believed to have betrayed his master. The picture fails hopelessly to give any real idea of the turmoil of battle, and it was probably well for the artist that it was not painted for Nadir Shah and seen by him. The Jeonits who saw Nadir Shah in Delhi, described him as “upwards of six feet high, and stout in proportion. He was burnt brown from campaigning and exposure to all weathers. . . . His glance was keen and piercing, his voice rough and rude, but which he could soften at pleasure. It was a face of power, on which was stamped courage and resolution, but his slightly projecting under lip gave an air of sinister fierceness and even cruelty to this great Captain.” When Nadir Shah and Muhammad Shah entered Delhi together, they were similarly mounted on a horse and on an elephant.

The Persian forces remained in Delhi from the beginning of March till early in June](1739 A.D.), has been described at page 51. No more heartrending picture of agony than the slaughters by the Persian king and Ahmad Shah (1756 A.D.), and the treatment of Shah Alam and his sons and ladies by the brutal Rohilla, Ghulam Kadir Khan, is presented by the most lurid pictures of history; and it is really a matter for wonderment that the Moghal empire survived at all, rather than that it survived for only so long as it did.

The causes of the decline and fall were many—decay of the original stock (which is what Timur’s Amirs wisely objected to when he proposed to make a permanent conquest of India), failure of the influx of fresh Muham.nadan military blood, after Kabul and Kandahar were lost to the Empire— internecine fratricidal wars upon each succession (it was always Takht or Takhta, the Throne or the Bier, with every son of the Emperor), which emptied the treasury and taught the great nobles and the Hindu chiefs how to use their power—the awful carnages of Nadir Shah and Ahmad Shah, the never-ending blood - sucking of Jat, Mahratta and Rohilla—the greed and treachery of ministers and royal eunuchs; and it is no matter for surprise that seventy years of these should have reduced the emperor of Delhi to the condition in which Lord Lake rescued Shah Alam II. in 1803.

It has already been narrated that when Nawab Safdar Jang, in the time of Ahmad Shah called in the Jats to his aid, his rival, Ghazi-ud-din, the younger, son of the elder Wazir of that name, summoned the Mahrattas to his side; the latter proved successful with the help of his allies, who had first appeared at Delhi thirty years previously in support of the Syad king-makers, and deposed and blinded the king. This brought Ahmad Shah Durani, now in possession of the West Punjab, again on the scene in 1756, and resulted in the sack of Delhi by the Pathans, but the Wazir managed to make terms with him, and remained in office with his support.

Four years later, upon the murder of Alamgir II., the Durani chief once more appeared at Delhi, and Ghazi-ud-din fled to the Jats, with whom he was present at Panipat previous to the battle. (It is a circumstance deserving note that this once powerful minister remained in hiding for some twenty years, and was then discovered at Surat, and enabled to proceed to Mecca by the assistance of the British East India Company.)

On this occasion Ahmad Shah remained near Delhi for a considerable time, and having finally crushed the Mahrattas at Panipat,1 in a battle fought on 7th January 1761, placed Ali Gauhar, the eldest son of the late king, and a refugee from Ghazi-ud-din, on the throne as Shah Alam II., under the Wazir-ship of Shuja-ud-daulah, Nawab of Oudh. The Jats re-appeared at Delhi as soon as the Pathans withdrew, and Suraj Mal was killed at Shahdera in 1764, and the Mahrattas, re-gathering power, presented themselves once more only a year after Shah Alam returned to Delhi in 1771. [1 Well might Panipat say with Ariminum : “Quoties Romam Fortuna lacessit, Hac iter est bellis.”]

Scindiah, himself, visited the capital in 1784; and, three years later, while the Mahratta prince was too deeply engaged in wars in Rajputanah to interfere immediately, the climax of the Moghal agony was reached on the capture of Delhi by Ghulam Kadlr Khan and his Rohillas, after they had been once compelled by the Begam Samru to withdraw. There is no more pathetic incident in the long history of the misery of this time than the reply of Shah Alam, when asked by the fiend who had blinded him whether he could still see: “I see only the Holy Koran between you and me.”

Three months afterwards the Rohillas were expelled by the Mahrattas, and not much later their leader met with his merited end For sixteen years the Imperial Court remained entirely subject to the Mahrattas, whose power and influence in North India was at last broken by the Battle of Delhi, on 11th September 1803 as their power in South India was broken at the Battle of Assaye twelve days later.

Shah Alam survived till 1806, and was then succeeded by his son Akbar II., who in his turn was followed in 1837—the year of the accession of Queen Victoria, first Empress of, and second Empress in, India—by the last King of Delhi, Bahadur Shah. The British Government had sought by all means in its power to secure a peaceful evening of life to the Imperial Dynasty which preceded it. But this was not to be, and its disappearance from the scene, fifty years later, was marked by one of the most blood-red sunsets ever painted on the canvas of history.

Historical tables of the Moghal Dynasty of India, adapted from the “Imperial Gazetteer of India,” prepared under the direction of Sir W. W. Hunter :

A.H. A.D. ZAHAR-UD-DIN MUHAMMAD BABAR BADSHAH HAZRAT GETI SITANI, 1526-30 : 932 1526 Defeat and death fof Ibráhim Lodí at Pánipat, and victorious entry of Bábar into Delhi and Agra.

” ” Capture of Jaunpur by Humáyun, son of Bábar.

” ” Surrender of Biána, Gwalior, and Múltán to his troops. 933 1527 Defeats Ráná Sanga at Fatehpur Síkri and assumes the title of Gházi.

” ” Occupation of Lucknow by Bábar’s army.

935 1529 Behar subdued.

” ” Final defeat of the troops of the Afghán coalition by Bábar’s army; treaty with Nasrat Sháh of Bengal 937 1530 Bábar’s death of Agra.

NASIR-UD-DIN MUHAMMAD HUMAYUN BADSHAH HAZRAT JAHANBANI, 1830-1556: A.D.

1530 . Accession to the throne. Capture of Lahore and occupation of the Punjab by his rival brother Kámrán. Final defeat of the Lodís under Mahmúd Lodí, and acquisition of Jaunpur by Humáyún.

1532 Humáyún’s campaigns in Málwá and Guzerat.

1539 Humáyún defeated by Sher Sháh, the Afghan ruler of Bengal, at Chapar Ghát, near Baxár, Retreats to Agra.

1540 Humáyún finally defeated by Sher Shah near Kanauj, and escapes to Persia as an exile. Sher Shah ascends the Delhi throne.

1556 Humáyún’s return to India, and defeat of the Afgháns at Pánipat by Bairám Khán and his young son Akbar. Remounts the throne, but dies in a few months, and is succeeded by Akbar.

JELAL-UD-DIN MUHAMMAD ABUL MUZAFFAR AKBAR SHAH, 1556-1605:

1542 Born at Umarkot in Sind.

1555-56 Succeeds his father after a few months in 1556, under the regency of Bairám Khán.

1560 Akbar assumes the direct management of the kingdom. Revolt of Rairám, who is defeated and pardoned.

1566 Invasion of the Punjab by Akbar’s rival brother Hákim Askari, who is defeated.

1561-68 Akbar subjugates the Rájput kingdoms to the Moghal Empire.

1572-73 Akbar’s campaign in Guzerat, and its re-annexation to the Empire.

1576 Akbar’s reconquest of Bengal, its final annexation to the Moghal Empire.

1581-93 Insurrection in Guzerat. The Province finally subjugated in 1593 to the Moghal Empire.

1586 Akbar’s conquest of Kashmír; its final revolt quelled in 1592.

1592 Akbar’s conquest and annexation of Sind to the Moghal Empire.

1594 His subjugation of Kandahár, and consolidation of the Moghal Empire over all India north of the Vindhyás as far as Kábul and Kandahár.

1595 Unsuccessful expedition of Akbar’s army to the Deccan against Ahmadnagar under his son Prince Murád.

1599 Second expedition against Ahmadnagar by Akbar in person. Captures the town, but fails to establish Moghal rule.

1601 Annexation of Khándesh, and return of Akbar to Northern India. 1605 His death at Agra.

NURUDDIN JAHANGIR BADSHAH, 1605-27 :

1605 Accession of Jahángír.

1606 Flight, rebellion, and imprisonment of his eldest son, Prince Khusrú.

1610 Malik Ambar recovers Ahmadnagar from the Moghals, and reasserts independence of the Deccan dynasty, with its new capital at Anrangábád.

1611 Jahángír’s marriage with Núr Jahán.

1612 Jahángir again defeated by Malik Ambar in an attempt to recover Ahmadnagar. First settlement of the English at Surat.

1613-14 Defeat of the Udáipur Rájá by Jahángír’s son Prince Sháh Jahán. Unsuccessful revolt in Kábul against Jahángír.

1615 Embassy of Sir T. Roe to the Court of Jahángír.

1616-17 Temporary reconquest of Ahmadnagar by Jahángír’s son Sháh Jahán.

1621 Renewed disturbances in the Deccan, ending in treaty by Sháh Jahán. Capture of Kandahár from Jahángír’s troops by the Persians.

1623-25 Rebellion against Jahángír by his son Sháh Jahán, who, after defeating the Governor of Bengal at Rájmahál, seized that Province and Behar, but was himself overthrown by Mahábat Khán, his father’s general, and sought refuge in the Deccan, where he unites with his old opponent Malik Ambar.

1626 The successful general Mahábat Khán seizes the person of the Emperor Jahángír. Intrigues of the Empress Nur Jahán.

1627 Jahángír recovers his liberty, and sends Mahábat Khán against Prince Sháh Jahán in the Deccan. Mahábat joins the rebel prince against the Emperor Jahángír.

1627 Death of Jahángír.

ABUL MUZAFFAR, MUHAMMAD SHAHAB-UD-DIN, SHAH JAHÁN, BADSHAH, SAHIB-I-KIRAIN SANI, 1628-58:

1627 Imprisonment of Núr Jahán on the death of Jahángír, by Asaf Khán on behalf of Sháh Jahán.

1628 Sháh Jahán returns from the Deccan and ascends the throne (January). He murders his brother and kinsmen.

1628-30 Afghán uprisings against Sháh Jahán in Northern India and in the Deccan.

1629-35 Sháh Jahán’s wars in the Deccan with Ahmadnagar, and Bijápur; unsuccessful siege of Bijápur.

1634 Sháji Bhonsiá, grandfather of Sivají, the founder of the Mahrattá power, attempts to restore the independent King of Ahmadnagar, but fails, and in 1636 makes peace with the Emperor Sháh Jahán.

1636 Bijápur and Golconda agree to pay tribute to Sháh Jahán. Final submission of Ahmadnagar to the Moghal Empire.

1637 Reconquest of Kandahár by Sháh Jahán from the Persians.

1640 English settle at Madras.

1645b Invasion and temporary conquest of Balkh by Sháh Jahán. Balkh was abandoned by Sháh Jahán’s army two years later.

1647-53 Kandahár again taken by the Persians, and three unsuccessful attempts were made by the Emperor’s sons Aurangzeb and Dárá Shekoh to recapture it Kandahár finally lost to the Moghal Empire, 1653.

1655-56 Renewal of the war in the Deccan under Prince Aurangzeb. His attack on Haidarábád, and temporary submission of the Golconda king to the Moghal Empire.

1656 Renewed campaign of Sháh Jahán’s armies against Bijápur.

1657-58 Dispute as to the succession between the Emperor’s sons. Aurangzeb defeats Dárá Shekoh; imprisons Murád, his other brother; deposes his father by confining him in his palace, and openly assumes the government. Sháh Jahán dies, practically a State prisoner, in the fort of Agra, in 1666.

ABUL MUZAFFAR AURANGZEB, BAHADUR ALAMGIK, 1658-1707:

1658 Deposition of Sháh Jahán, and usurpation of Aurangzeb. 1659 Aurangzeb defeats his brothers Shujá and Dárá Shekoh. Dárá Shekoh, in his flight being betrayed by a chief with whom he sought refuge, is put to death by order of Aurangzeb.

1660 Continued struggle of Aurangzeb with his brother Shujá, who ultimately fled to Arakan, and there perished miserably.

1661 Aurangzeb executes his youngest brother, Murád, in prison.

1662 Unsuccessful invasion of Assam by Aurangzeb’s general Mir Jumlá.

Disturbances in the Deccan. War between Bijapur and the Mahrattás under Sivají. After various changes of fortune, Sivají, the founder of the Mahrattá power, retains a considerable territory.

1662-65 English settle at Bombay. Sivají in rebellion against the Moghal Empire. In 1664, he assumed the title of Rájá, and asserted his independence; but in 1665, on a large army being sent against him, he made submission, and proceeded to Delhi, where he was placed under restraint, but soon afterwards escaped.

1666 Death of the deposed Emperor, Sháh Jahán. War in the Deccan, and defeat of the Moghals by the King of Bijápur.

1667 Sivají makes peace on favourable terms with Aurangzeb, and obtains an extension of territory. Sivají levies tribute from Bijápur and Golconda.

1670 Sivají ravages Khándesh and the Deccan, and there levies for the first time chauth, or a contribution of one-fourth of the revenue.

1672 Defeat of the Moghals by Sivají.

1677 Aurangzeb revives the jaziah or poll-tax on non-Muhammadans.

1679 Aurangzeb at war with the Rájputs. Rebellion of Prince Akbar, Aurangzeb’s youngest son, who joins the Rájputs, but whose army deserts him. Prince Akbar is forced to fly to the Mahrattás.

1672-80 Mahrattá progress in the Deccan. Sivají crowns himself an independent sovereign at Ráigarh in 1674. His wars with Bijápur and the Moghals. Sivají dies in 1680, and is succeeded by his son, Sambahjí.

1681 Aurangzeb has to continue the war with the Rájputs.

1683 Aurangzeb invades the Deccan in person, at the head of his Grand Army.

1686-88 Aurangzeb conquers Bijápur and Golconda, and annexes them to the Empire (1688).

1689 Aurangzeb captures Sambahjí, and barbarously puts him to death.

1692 Guerilla war with the Mahrattás under independent leaders.

1698 Aurangzeb captures Jinjí from the Mahrattás.

1698 English purchase Calcutta.

1699-1701 The Mahrattá war. Capture of Sátára and Mahrattá forts by the Moghals under Aurangzeb. Apparent ruin of Mahrattás.

1702-05 Successes of the Mahrattás.

1706 Aurangzeb retreats to Ahmadnagar, and 1707 Dies there (February).

THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE MOGHAL EMPIRE,

From death of Aurangzeb to that of Muhammad Bahádur Sháh. 1707-1862 1707 Succession contest between Muázzim and Alam, two sons of Aurangzeb; victory of the former, and his accession under the title of Bahadur Sháh, Revolt of Prince Kambatsh; his defeat and death.

1710 Expedition against the Sikhs.

1712 Death of Bahádur Sháh, and accession of his eldest son Jahándar Sháh, after a struggle for the succession; an incapable monarch. Revolt of his nephew, Farukhsiyar; defeat of the Imperial Army, and execution of the Emperor.

1713 Accession of Farukhsiyar, under the auspices and control of Husáin Alí, Governor of Behar, and Abdullá, Governor of Allahabád.

1716 Invasion by the Síkhs; their defeat, and cruel persecution.

1719 Deposition and murder of Faruthsiyar by the Sayad chiefs Husáin Ali and Abdullá. They nominate in succession three boy Emperors, the first two of whom died within a few months after their accession. The third, Muhammad Sháh, commenced his reign in September 1719. 1720 Murder of Husáin Alí, and overthrow of the Sayad “kingmakers.”

1720-48 The Governor of the Deccan, or Nizám-ul-mulk, establishes his independence, and severs the Haidarábád Provinces from the Moghal Empire.

1732-43 The Governor of Oudh, who was also Wazír of the Empire, becomes practically independent of Delhi.

1735-51 General decline of the Empire; revolts within, and invasion of Nádír Sháh from Persia (1739).

The Mahrattás obtain Málwí (1743), followed by the cession of Southern Orissa and tribute from Bengal (1751). First invasion of India by Ahmad Sháh Durání, who had obtained the throne of Kandahár (1747); his defeat in Sirhind (1748).

1748 Death of Muhammad Sháh.

1748-50 Accession of Ahmad Sháh, his son; disturbances by the Rohillá Afgháns in Oudh, and defeat of the Imperial troops.

1751 The Rohillá insurrection crushed with the aid of the Mahrattás.

1751 Second invasion of India by Ahmad Sháh Durání, and cession of the Punjab to him. Siege of Arcot.

1754 Deposition of the Emperor, and accession of Alamgír II.

1756 Third invasion of India by Ahmad Sháh Durání, and sack of Delhi. 1757 Battle of Plassy.

1759 Fourth invasion of India, by Ahmad Sháh Durání, and murder of the Emperor Alamgír II. by his wazir, Gházi-ud-din. The Mahrattá conquests in Northern India. Their organization for the conquest of Hindustan, and their capture of Delhi.

1761-1805 The third battle of Pánipat, between the Afghans under Ahmad Sháh and the Mahrattás; the defeat of the latter. From this time the Moghal Empire ceased to exist, except in name. The nominal Emperor on the death of Alamgír II. was Sháh Alam II., an exile who granted the Diwani of Bengal to the East India Company in 1765, and resided till 1771 in Allahábád, a pensioner of the British. In the latter year, he threw in his fortunes with the Mahrattás, who restored him to a fragment of his hereditary dominions.

The Emperor was blinded and imprisoned by Rohilla rebels. He was afterwards rescued by the Mahrattás, but was virtually a prisoner in their hands till 1803, when the Mahrattá power was overthrown by Lord Lake, Sháh Alam died in 1806, and was succeeded by his son.

1806-1837 Akbar II., who succeeded, only to the nominal dignity, and lived till 1837; when he was followed by

1837-1862 Muhammad Bahádur Sháh, the seventeenth Moghal Emperor, and last of the race of Timúr. For his complicity in the Mutiny of 1857, he was deposed and banished for life to Rangoon, where he died, a British State prisoner, in 1862.

LATER EVENTS.

1859 Assumption of the direct Government of India by the Crown.

1876 Visit of His Imperial Majesty King Edward VII., as Prince of Wales, to Delhi.

1877 1st January. Proclamation of the Imperial títle at Delhi.

1803-1857

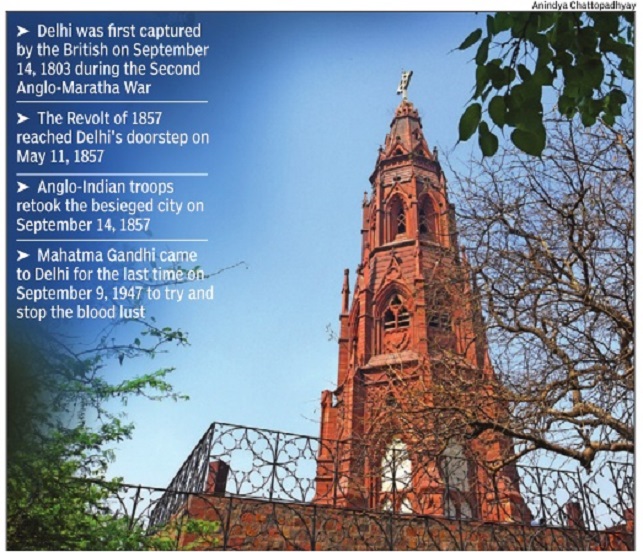

Not very far from where our TOI office in Delhi stands today [on Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg] raged the fierce Battle of Delhi on September 11, 1803.

Maratha general Daulat Rao Scindia, as the Mughal subedar of Agra and Ajmer, held sway over most parts of northern India. He was also, in an Oliver Cromwellish way , the lord protector of Del hi and Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II.

Scindia's formidable Fauj-iHind or Army of Hindustan clashed swords with a smaller Anglo-Indian army led by General Lord Ge rard Lake, Commander-inchief of India. The Marathas were beaten, and on September 14, 1803, John Company's forces took Delhi.

Exactly 54 years later, on September 14, 1857, another Anglo-Indian army emerged victorious in the Siege of Delhi and retook the Mughal capital amid bloody fighting.History had repeated itself.But for Delhi, the Revolt of 1857, which had begun in Meerut on May 10, and had landed at its doorstep on May 11, had effectively ended. And with it ended the Mughals and the East India Company .Delhi changed forever.

Almost all the Muslims and those Hindus who sided with the rebels were banished from the Mughal capital even as the British bestowed favours on traders and merchants who supplied the British forces while they were stationed on the Ridge.

“The refined and courtly culture of Delhi was eroded with the vanishing of the court and a significant chunk of its original population. Delhi that rose out of the ashes of the Revolt was markedly different,“ says Rana Safvi, who has recently translated an Urdu eyewitness account of the Revolt called Dastan-eGadar by Zahir Dehlvi into English.

After Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India at the Durbar of 1877, those banished from Delhi were allowed to return. Not many came back, though. One of the families that had left Delhi in 1857 was the Nehru family . Gangadhar Nehru was the Mughal kotwal of Delhi when the Revolt broke out.And though they either retai ned their ancestral haveli or got it back in 1877, they chose to settle down in Allahabad.

Ninety years after the Revolt, as India became independent amid Partition in 1947, Delhi suffered again, this time irreversibly . Bloo dy communal riots gripped the capital even as a two-way exodus of people began. Watching over Delhi in this critical hour was Jawaharlal Nehru as the first Prime Minister of free India. The great grandson of the last kot wal of Delhi urged his mentor to come to the capital.

And Mahatma Gandhi acceded to this request. In September 1947, Gandhi took up residence in the frenzied city for one last time. As history tells us, he would lay down his life in his fight to restore peace and communal amity .India paid a heavy price for peace, yet Gandhi's ahimsa triumphed over hate.

But back in 1857, it was hate that won: first when the rebel sepoys captured Delhi, and then again when the English won it back and unleashed their “retributive justice“.

As this storm raged over Delhi, the sort of `garam hawa' that Ismat Chughtai would write about in reference to the Partition, the Mughal emperor became a virtual prisoner, for life as later events would tell us. Indeed, Bahadur Shah Zafar was a tragic victim of circumstances. So powerless was he that he couldn't even prevent the massacre of 52 European civilians he had sheltered in the fort.

Yet Indians almost forgot 1857. But the British didn't: it lived on in their collective consciousness. Arvind Sharma writes in his latest book The Ruler's Edge: “It's said that there were three things that every schoolboy in England knew about India: the Black Hole, Plassey and the Mutiny .“

Delhi in the 1840s

Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, What Delhi lost in 170 years since 1847, August 26, 2018: The Times of India

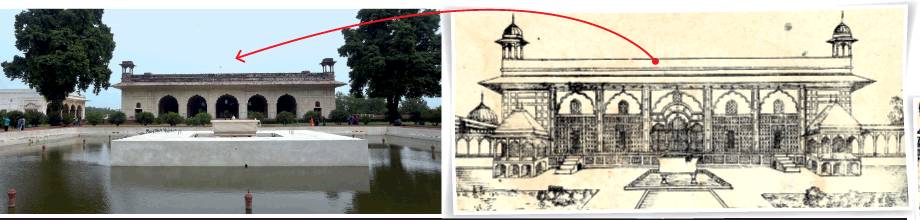

Rare Lithographs Of 1840s Show How Delhi’s Iconic Monuments Looked Like A Decade Before The Mughal Empire Ended And How They Were Lost Or Eroded With Time

In the 1840s, a young archaeologist suspended himself from a balcony of the Qutub Minar in a basket held by ropes. He put his life and limb in peril just to copy the inscriptions on the uppermost parts of the minaret. That energetic youngster eventually became known as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, founder of Aligarh Muslim University. And the work he did then became part of a monumental tome named Asar-us-Sanadid that came out in 1847, with a revised edition in 1854.

Written in Persianised Urdu, it was an account of the most prominent monuments of Delhi, including the Red Fort where the Mughal emperor still held court. What was also unique: it contained 130 lithographs prepared by Faiz Ali Khan and Mirza Shahrukh Beg. Yet for over 170 years, this resource remained unavailable to people who couldn’t read Urdu.

All that has changed now with historian Rana Safvi translating it into English and editing it.

The Delhi that Sir Syed had documented was ravaged by the Revolt of 1857. But the stunning lithographs based on his own sketches got TOI curious to find out how some of these monuments exist (or not) on the ground today. We tried to capture them from the same angles that Sir Syed had captured them in his sketches. It was some contrast.

Rana Safvi was with us in this journey of exploration. We started with the Red Fort, which is today only about 20% of what it originally was, the rest having fallen victim to British retribution. Sir Syed was already lamenting that the palaces have lost their old glory; today, the lament has become a heart-breaking cry of loss.

“I was shocked to see the contrast! The British destroyed so many buildings inside the fort, including the Moti Mahal that was knocked down just because the British felt it blocked the breeze from the Yamuna from flowing towards the barracks. Such was the callousness with which Delhi was destroyed,” Safvi told us.

The Naqqar Khana had arcades that were smashed clean; the Diwani-Aam had arcades too that were knocked down and its courtyard turned into an English-style lawn; the Imtiaz Mahal, an ornate palace gilded with gold, is a wreck today.

At the Purana Qila, the Sher Mandal stands tall from the time of Sher Shah Suri. When Sir Syed sketched it, it was surrounded by hutmentsthe village of Indarpat existed here, which was later evicted when the British were making New Delhi. Today, amid a properly landscaped terrain, the Sher Mandal stands in peace, free of clutter.

The Khooni Darwaza was another contrast. When Sir Syed documented it, it was known as Kabuli Darwaza. To the right of it when seen from Delhi Gate were a Mughal jail and another building called Mehdiyan. Today, even the Khooni Darwaza is hidden amid thick foliage while Maulana Azad Medical College stands where Mehdiyan once stood. Heritage was forced to make way for modern growth.

Sir Syed wouldn’t have recognised today’s Delhi.

1857

Monuments associated with the events of 1857

Manimugdha Sharma, A WALK THROUGH THE RUINS OF 1857, May 11, 2017: The Times of India

May 11, 1857. Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar was fishing in the Yamuna in the morning when he was told about some disturbance breaking out in the city . He rushed back into the fort.

Sowars of the 3rd Bengal Native Cavalry , after mutinying at Meerut the previous day , had reached Delhi after riding overnight. The Revolt of 1857 was at Delhi's doorstep. And the octogenarian head of the house of Timur, given to poetry and not soldiering, was thrust into the command of an epic struggle that was not just political but also cultural: one that would change Delhi and India forever.

On May 5, TOI approached India's foremost military historian, Squadron Leader Rana T S Chhina (Retd) of USI-CAFHR, to walk us through the landmarks of the Revolt in Delhi: the ruins, the battlefields, the memorials. The trigger for it was obvious: it's the 160th anniversary of the Revolt, which people variously refer to as the Indian Mutiny , Sepoy Mutiny , and First War of Indian Independence, depending on which side of the ideological or cultural spectrum they are located.

We, along with a delegation from the British High Commission, assembled outside DU vice-chancellor's residence, facing the road to Flagstaff Tower. It was a hot May morning, like the one that troubled Jim Corbett when he hunted down the Mohan man-eater. But we endured it as we were hunting for history.

In 1857, the rebel troops started killing Christians, both white and brown, once they were in the city. Europeans who managed to escape flocked towards Flagstaff Tower--our first stop.

One just has to peek inside to imagine how in this rat hole of sorts, scores of people-many of them women and children--huddled together in the searing heat, waiting for help to arrive from Meerut.

We turned left from the Flagstaff Tower into Bonta Park. A little ahead, we arrived at a 19th-century guard house, one of the two that still exist and which would have had an Indian picket when the Revolt began--Delhi was garrisoned by the 38th, 54th and 74th Bengal Native Infantry regiments.

By early June, however, the British reinforcements came and a counterattack began.Flagstaff Tower had a rebel battery by then, which rained down fire and hell on the ap proaching Anglo-Indian troops. “Despite the bitter animosity that existed then between the British and the rebels, the British officers were appreciative of the gunnery of the rebels.Indian guns were serviced very well, and the English noted that an Indian gunner would rather die defending his gun than give it up,“ Chhina said.

Some English officers also heaped praise on the rebels for orderly retreat under fire and took pride in training the men well.

The Tower was taken and it became the left flank of the British position on the Ridge; the centre of the position became the Mosque Picket, our next halt. It's actually the Chauburja Masjid or the four-domed mosque built by Sultan Ferozeshah Tughlaq in the 14th century . Chhina showed us how it appeared to European photographer Felice Beato in 1858 while we tried to capture the mosque from the same angle as Beato did. Only one dome exists now--a sorry testament to the conservation story of modern India. Next we went to a palace of Ferozeshah Tughlaq, which is now called Pir Ghaib but may have been the Kushk-iJahanuma or Kushk-iShikar, a hunting lodge of the Delhi sultan. Even Tamerlane may have visited it. In 1857, this was the scene of bitter fighting between rebel troops and British-led troops. The baoli right next to it is a wonder in itself with flights of stairs on all sides. English troops back in 1857 reported seeing a step well with several leafy trees near Hindu Rao's house. Only the stumps of some of those trees remain today.

Hindu Rao's house was the next halt. In June 1857, it was held by the Sirmoor battalion of the Gurkhas supported by other units. On September 14, the British stormed Delhi with their full might. The Siege of Delhi ended amid mind-numbing carnage. “Passions were excited on both sides. And it was Delhi that suffered.“ Chhina said.

As one contemporary observer noted, Delhi became a “ghost city“ with abandoned homes and bloated corpses lying all over.

Our final stop was the Mutiny Memorial on the Ridge, now called Ajitgarh or Fatehgarh. Today , it's a nationalised memorial to both Indians and the English killed during the Siege of Delhi.

“Something must be done to make these places more familiar to tourists. And these must be preserved,“ said Lieutenant Colonel Simon de Labilliere, the military adviser at the high commission.

See also

Delhi: History (730- 1911)

Delhi: the Battle of Delhi, 1803