Delhi: Lutyens

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The philosophy behind the architecture and town planning

The vision of the British government

Adrija Roychowdhury, December 12, 2022: The Indian Express

On December 12, 1911 at the grand coronation durbar held in Delhi, King George V announced the shifting of the British capital in India from Calcutta. Delhi, the city of the great Sultanate kings and Mughals was to serve as the new capital of British India. The decision raised important questions. How was the new seat of the imperial government to be conceived in stone? What was the architecture of British Delhi to look like? What would be the most ideal site for its location? How would land be acquired? How should the multiple administrative buildings be aligned? Weeks and months of debate would go into deciding the precise look and feel of New Delhi. Yet at the durbar of 1911, the King made it very clear: “It is my desire that the planning and designing of the public buildings to be erected will be considered with the greatest deliberation and care, so that the new creation maybe in every way be worthy of this ancient and worthy city.”

The transfer of the British capital came at a crucial moment of colonial history in India. The decision was taken in the backdrop of Viceroy Lord Curzon’s disastrous decision to partition Bengal in 1905 and the massive political unrest that followed. “A move undertaken in large parts to enable the government to escape the uncomfortable political atmosphere of Calcutta, marked by continued and often violent demonstrations of nationalist sentiment since Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal,” writes historian Thomas R. Metcalf in his book, ‘An imperial vision: Indian architecture and Britain’s Raj’.

Thereafter, the move to Delhi was to symbolise a new alliance with Indians for whom the city had historical associations. “It was an altogether different kind of empire that was being envisaged, which saw a greater devolution of power to the provinces, and by implication a system that was more responsive to local Indian needs,” writes historian Swapna Liddle in her book, ‘Connaught place and the making of New Delhi.’ She underlines the symbolic importance of Delhi in this regard: “If an overarching imperial structure was to be the future of the British Raj, no better capital could be found that Delhi – the seat of the great erstwhile empires of India. Since the early thirteenth century it had functioned, with a few interregnums, as a capital of important powers – the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal empire.”

A consequence of an image makeover of an empire more suited to Indian needs was that the latter’s art and architectural achievements needed to be given space in the new capital. The strongest proponent of an Indian inspired architecture was the then viceroy, Lord Hardinge. “The architecture of the new capital, he insisted, must be imbued with the spirit of the East such as will appeal to orientals and well as to Europeans,” writes Metcalf. Hardinge believed that this was of political importance as he wrote to Curzon that Indians must not be made to feel that they have no say in the design of the new capital but only be asked to pay for it.

The capital debate

Hardinge’s view was just one side of the debate. He was of course joined by prominent British statesmen and architectural experts who believed that the transfer of the capital to the Mughal heartland provided an opportunity to emulate the great imperial predecessors, especially Akbar who built Fatehpur Sikri and Shah Jahan who created Shahjahanabad. EB Havell, the retired principal of the Calcutta School of Art, for instance, wrote in The Times campaigning for an Indic Delhi. “With the move to Delhi, the capital will leave the commercial atmosphere of Calcutta, with its shoddy imitations of European architecture, and find itself in the heart of Hindustan,” he wrote adding that the British government needed to call into service the skills of Hindu temple builders and adapt Mughal designs effectively.

Meanwhile, in February 1913, a group of prominent artists, scholars, and members of both houses of the Parliament in Britain wrote a petition to the India Office asking for the employment of Indian craftsmen in the building of the new capital. In so doing, they wrote, the British government would “tie the natives of India more closely to the mother country.”

Metcalf in his book writes that the enthusiasm for an Indic Delhi was deemed all the more necessary given the nationalist political climate and the fear of what it might hold for British rule in the country. A sense of urgency marked their pleas as they called for a capital city that spoke to Indians in familiar architectural language and provided employment of their traditional crafts.

The strongest opposition to the use of traditional Indian architecture though came in from the architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker. Lutyens, most often credited to being the face that built New Delhi, was in fact most disdainful towards Indian architectural traditions. Soon after he arrived in Indian in March 1912, he wrote to his wife, “I do not believe there is any real Indian architecture or any great tradition. There are just spurts by various mushroom dynasties with as much intellect as there is in any other art nouveau.”

Lutyens was a firm believer in the European classical forms of architecture, “He was dismissive of Hardinge’s ideological concerns, saying, ‘I do want old England to stand up and plant her great traditions and good taste where she goes and not pander to sentiment and all this Moghul-Hindu stuff’,” notes Liddle.

Lutyens’ staunch stance against Indian artistic skills though, was balanced by the other architect in the town planning committee, Herbert Baker who was most well known for his work in South Africa as the creator of the Pretoria Union buildings. Baker was closer to Hardinge in his belief that the architecture of Delhi needed to speak of its imperial ideologies. However, unlike Lutyens he was of the opinion that the objective would be achieved by an intermingling of Eastern and Western styles. But he did agree with Lutyens on the superiority of European classicism, upon which he said that Indian traditions had to be grafted.

The third architect, Swinton Jacob was appointed as an architectural advisor. Jacob had a long career in India and had mastered the Indo-Saracenic style as he designed prominent buildings like the St.Stephens College in Kashmiri gate and the Canning and Medical colleges in Lucknow. “Hardinge hoped that Jacob would ensure that Indian features were used in New Delhi’s architecture,” writes Liddle. But Jacob frequently came into conflict with Lutyens over his emphasis on the use of Indian elements like Chhajja (a projecting stone cornice, placed below a parapet to provide shade from the sun) and chhattris (cupolas supported on pillars). Finally, Jacob resigned in August 1913, but not before putting in a suggestion that the only way to incorporate the spirit of India in British Delhi was through the involvement of Indian master builders.

However, that was not to be. “It was finally decided that though there was a need to incorporate an Indian flavour into the architectural style of the new capital, one did not really need expert advice from Indians,” notes Liddle. A press release from the government in 1914 noted that the architects would not build in any particular style but would be structurally adapted for the use which it required. At the same time, Indian elements would serve as decoration. “The peculiar genius of the Indian workman lies in ornament and decoration,” noted the release.

The Indian elements in European Delhi

As a means to find inspiration from ancient and medieval Indian architecture, Hardinge induced Lutyens and Baker to visit most of the ancient and medieval sites of northern and central India like Mandu, Lahore, Lucknow, Kanpur and Indore. Three characteristic Indian features that seemed to Baker to be appropriate for the imperial capital was the chhatri, chhajja and jaali (pierced stone lattice screen). Along with these, Hardinge himself pressed for the inclusion of the four centred pointed Mughal arch. He wrote Lutyens, “In the East the pointed arch is a symbol, and has a meaning which all Indians understand, while a round arch means nothing at all.”

Finally, the Viceroy’s house which is today the Rashtrapati Bhawan projected an architecture which expressed the ideals of the British empire, while assimilating Indian elements at a subordinate level. “The massive dome and gigantic colonnades, their authority derived from the traditions of European classicism, marked out clearly Britain’s sovereignty over the Indian subcontinent,” writes Metcalf. The Indian features were evident in the use of the overhanging chhajja, the clustered chhattris and the railing around the dome derived from the Sanchi stupa. “Further Indic elements were almost playfully introduced, among them a cobra fountain and a colonnade of trabeated arches in the kitchen entrance,” adds Metcalf. Equally interesting to note is the enthusiastic placement of carved elephants across the complex.

There is also the conjecture of famous Indian temples and monuments serving as inspiration for the buildings being designed by the British. “Lutyens and Baker were sent off this tour to look at examples of Indian architecture. They also might have seen photographs collected by the Archeological Survey of India. So even though there is no proof of them emulating Indian monuments, it is not inconceivable that they might have done so,” says Liddle over the phone. “For instance, the fact that the Sanchi stupa was the model for the Rashtrapati Bhavan is quite obvious,” she says.

Similarly, one is often struck by the similarity in structure and design of the Parliament House and the Chausath Yogini Temple at Mitawli village in Morena district near Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh. “Again we have no proof that they went to Mitawli or that they saw this temple, but at the same time it is not inconceivable that it might have served as an inspiration,” says Liddle.

Interestingly, the Parliament house was not originally part of the capital complex plan. It was built in response to the Government of India Act of 1919 which was meant to increase participation of Indians in the government. A bicameral legislature was created and this meant that the administration had to find space for legislative chambers for two houses. “The Parliament House was one building which was meant for Indians right from the beginning,” says Liddle. “But by then the debate over style was already over and the same philosophy that guided the creation of the other parts of the capital complex is followed here,” she adds.

Despite the grandeur of the project, scholars of modern Indian history have often interpreted the building of New Delhi as the beginning of the end of British rule. “Lutyens’ use of Indic features too, while innovative, reflected the loss of imperial self-confidence,” notes Metcalf. Despite the many ways in which the British government wanted to reinvent itself in the building of a new capital, the outset of World War II, the rising expenses that followed and of course a raging nationalist spirit in India, all led the way towards the end of the empire. As Metcalf most fittingly notes, “The Viceroy’s House did not point the way towards a new architecture that might define a new relationship between India and Britain….it led inevitably, nowhere.”

Lutyens' vision

The Times of India, Aug 29 2015

Lutyens planned Delhi with a garden city in mind

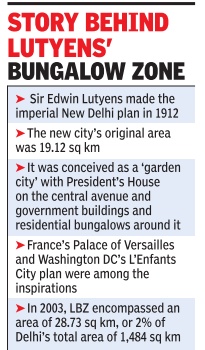

When Sir Edwin Lutyens sat down at his drawing board to design Imperial New Delhi just over 100 years ago, he was inspired by the ideas of the Garden City Movement started by another English architect, Ebenezer Howard, in the late-1800s. The movement, an urban planning concept, saw a city as a group of planned, self-contained communities surrounded by green belts “containing proportionate areas of residence, industry and agriculture“. So Lutyens' Delhi, also known as the “Eighth City of Delhi“, stood out from the start with wide tree-lined avenues, large plots and spacious bungalows set in them. The President's House was set on a central avenue surrounded by government buildings and residential bungalows.

Lutyens unveiled his plan in 1912 and the new city , occupying 19.12 sq km, was built over 20 years. Located to the south of Shahjahanabad, it quickly became the seat of the rich and influential.

“The city was laid out in a grand manner and is an excellent example of a fine blend of classical and modern town planning. It lay on an east-west axis, starting at Rashtrapati Bhavan atop Raisina Hill and terminating at the India Gate `C' hexagon, said an official.

Even Delhi's hot and dry summers were factored into the design.“Rashtrapati Bhavan, North Block and South Block, large bungalow plots and other government buildings knit together carefully by a web of wide shady avenues lend to the city a grand order, symmetry and unique aesthetic character, says a description of Lutyens' Bungalow Zone (LBZ).

Besides the Garden City Movement, France's Palace of Versailles and Washington DC's L'Enfants City plan also provided Lutyens with inspiration. The hundreds of bungalows were designed by well-known British architects like WH Nicholls, CG Blomfield, Walter Sykes George and Arthur Gordon Shoosmith.

Experts say LBZ is unique and the only `new town' in the world inspired by the (much-modified) Garden City Movement. But the urban development ministry says LBZ should not be compared to Howard's `garden city' because it was envisaged as a suburb to a central city, while LBZ is the heart of New Delhi.

Swachh Survekshan

2017, NDMC 7th cleanest

Alok K N Mishra, New Delhi cleanest in north: Swachh survey, May 05 2017: The Times of India

The New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) area was declared the cleanest in the north, based on solid waste management, access to sanitation and other parameters of cleanliness, under the zone-wise Swachh Survekshan 2017.

NDMC finished seventh among 434 cities in the national ranking, slipping three notches from the fourth position it had bagged among 73 cities in 2016 and eight points above the 15th position it got in 2014.

NDMC is responsible for civic amenities in the 42.7 sq km area covering Lutyens' Delhi, besides Connaught Place and residential areas like Moti Bagh, INA Colony , Jor Bagh, Kidwai Nagar and others.NDMC secured 1707.96 out of 2,000 on various parameters in the survey conducted by the urban development ministry . The NDMC area has be come 100% open defeca tion free -the practice was earlier seen in slums located in Moti Bagh and some other places.

NDMC scored 819.95, 426.88 and 461.13 under municipal documentation, direct observation and citizen engagement, respectively . The council is elated, but chairman Naresh Kumar is gunning for the first position in Swachh Survekshan 2018 for which he has asked the officials to step up efforts.

NDMC has also devised a strategy to achieve top position. An official said the strategy for 2017-18 will be to segregate 100% waste at source from June 5. “We have decided to make five colonies zero-waste colonies.“ NDMC has already constructed 330 public toilets, 63 public toilets are under construction which will be completed by September . “We have become the first open urination free city,“ said an official.

To check waste generation in the form of plastic bottles, NDMC is installing water ATMs at public places. To improve its public toilets, NDMC will install machines for public feedback at public utilities to improve the level of maintenance and citizens' perception.

A door-to-door waste collection system covers the entire area of NDMC and over 75% of all notified commercial areas are swept twice a day using mechanised sweepers.

NDMC spokesperson M S Shehrawat told TOI: “The urban development ministry has observed that a slide in ranking does not mean that we had compromised in extending quality civic services to citizens and did not maintain the upkeep of cleanliness at par with the previous year.“

For awareness campaign and behaviour change, one of the key parameters, NDMC got 33 out of 50. NDMC claimed that it has undertaken an extensive campaign to create awareness about the segregation of waste at source. “Members of RWAs, volunteers of NGOs and students are going household to household to sensitise people about the importance of health and hygiene,“ said an official.

On solid waste management, NDMC scored well for 80% of its wards being covered by door-to-door waste collection, informal waste-pickers being deployed in more than 50% wards, for an operational waste processing plant. NDMC has less than 10% vacancy in solid waste management; more than 90% staff in waste management, sanitation service have undergone different training courses, among other infrastructure.

The evaluators reached the conclusion on the basis of data provided by the council besides data collection through independent observation and assessment and collection of direct citizen feedback.