Delhi: Mehrauli town, archæological park, Andheriya Morh

Contents |

Delhi: Mehrauli town in 1902

This section was written between 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

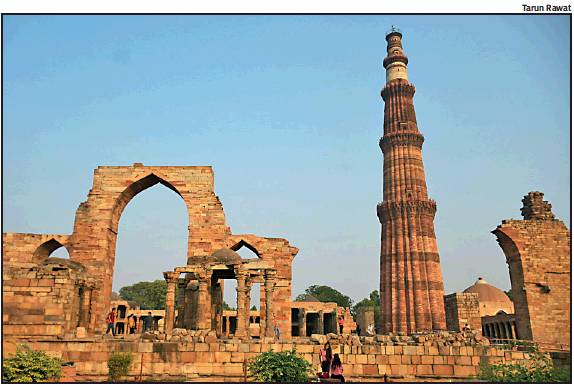

The roadside trees hide the

view of the Kutab Minar. Just half a mile from the outer line of defences the east wall of the

citadel is reached, and immediately beyond it the Kutab enclosure. The tomb of Adham Khan,

200 yards beyond this enclosure stands on the south wall of the citadel, and the road ascends

to this and then falls to the level of the Mahrauli bazar, built outside the southern line of the

defences.

It is another curious coincidence that the oldest Hindu citadel at Delhi should have been called the Lal Kot, and the latest Muhammadan fortress, the Lal Kila. Every one who can, should walk along the outside of the west wall of the Lal Kot from Adham Khan’s tomb to the picturesque grave of the martyr-warrior Baba Roz Beh in the ditch, and should return through the Fort past the tank of Anang Pal II. by the Ranjit Gate, or, better, by the north-west corner of the wall and the Fatah (Victory) Bastion, from which there is a fine view to the north.

It will be borne in mind that at the Kutab we are in the midst of the memorials of the Muhammadan conquest, not mere invasion, of India, and that these date from 1191 A.D., the year of that conquest, to 1315 A.D., when the Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji died. Like the Láts of Asoka in the Delhi of Firoz Shah, the iron pillar in the centre of the Kutab Mosque is a transferred memorial of an earlier age, probably the fifth or sixth century A.D., and the carved pillars in the corridor of the original mosque may be of any date between fifty and two hundred years before 1200 A.D.

The mosque and the buildings round it (of which the disposition will be understood from the annexed plan, taken by kind permission of Messrs Murray from Mr Fergusson’s “Eastern Architecture,” and completed with various details) are the work of three great kings, who, with the Emperors Balban and Firoz Shah exhaust the rulers of that class previous to the Moghal conquest of India; first, Kutab-ud-din-Aibak (1206 – 1211), who built the innermost court of the mosque, with its corridors and west end, in 1191, and added the screen of arches in front of the west end of the court six years later; secondly, Shams-ud-din Altamsh [Iltutmish] (1211- 1236), who completed the Kutab Minar commenced by his predecessor, added the outer arches of the screen north and south of these of Kutab-ud-din, and built a fresh courtyard, with a cloister of pillars specially prepared for it, extending along the south side as far east as the Kutab Minar, and on the east side still standing opposite the north end of the front of Kutab-ud-din’s Mosque, and whose tomb is situated outside the north - west corner of the mosque as enlarged by him; and thirdly, Ala-ud-din Khilji (1295-1315 A.D.) who built the beautiful Alai Darwazah almost under the Kutab Minar, continued the south corridor of Altamsh past this gate, very much further east, and carried it north, so as to include his unfinished minar outside the north-east corner of the mosque as enlarged by Altamsh, made a further extension of the screen of arches to the north, and joined these two extensions along the north side.

On the south side the enclosure terminates on the edge of a deep depression below the Alai Darwazah, so no extension of the arches was possible there. Ala-ud-din’s tomb stands in the south wall of the enclosure behind the mosque, as first enlarged, and corresponds with that of Altamsh.

Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque

The Mosque of Kutab-ud-din, known as the Kuwat [ Quwwat]-ul-Islam, or “Might of Islam,” is, roughly speaking, 150 feet to the front and back, and half as much again from side to side: the open courtyard in the centre of it is 108 feet by 142 feet.

The gates on the east and north sides are still complete, and bear inscriptions relating to the foundation. The gate on the south side has disappeared, together with much of the west end and the whole of the western colonnade of the south wall.

Though built entirely of Hindu, or rather Jain materials, every portion of the mosque was rebuilt by the conquerors: the opinions that the plinth of the court and the pillars behind the great screen of arches are in situ as erected by the Hindus, are equally erroneous. Originally the exterior of the walls was, no doubt, entirely covered by plaster, as the columns inside were, but this has all disappeared.

The view through the east gate is very pleasing, and the view down the vista of columns on either side of the central dome of the east corridor is extremely buautiful. This corridor is practically complete, but only about three-quarters of the north corridor are so, and very little of the south corridor and its plainer columns now remains.

The most beautiful columns are in the north side of the east arcade, and the carving of flower vases, with foliage falling from them, conventional leopards’ heads with garlands, ropes with tassels, bells on chains, and many floral designs, deserve to be carefully examined. On the fifth pillar to the north from the centre in the second row from the wall is a relief of a cow and a calf, and in the same line, fifth, on the edge of the courtyard, is, perhaps, the most beautiful of all the pillars.

Many half-effaced Jain figures,1 and not a few undamaged ones, which could be completely concealed by the plaster, will be noticed on the columns.

[1 Those who have visited the beautiful little Kora Mosque (Χώρα тŵv Ζώvтωv—it is known to the Turks as Kahriyah Jamisi) in Constantinople, in order to see the very interesting Byzantine mosaics, which are now no longer hidden by whitewash and plaster, will remember that the heads and faces of angel figures on the capitals of the columns in the narthex, and by the baptistery there, have been broken and disfigured in the same way as the heads in the cloister of the Kutab.]

The galleries in the corner of the arcade should be visited both for the sake of the beautiful ceilings of the domes and the carved scenes with elephants and horses on the beams across the corner of the side compartments of the roof; the numbering on the various stones of the pillars under the south gallery is interesting.

The carved scene on the stone above the second window from the front on the outer side of the north wall should also be noticed. It represents, in a mediæval way, the birth of Krishna, the child and its nurse being shown several times over in the same scene. The two scenes are divided by a half open door, and at the end of that towards the west are represented a cow and a calf, which produces a strong resemblance to the Sacred Manger scene.

The floor of the courtyard is slightly higher than that of the arcades, and drains are cut through the latter to the outside. The iron pillar stands in the centre of the court, as measured from north to south, rather more than half-way up the west half of it; besides the pillar there are several graves in the area, and it is tempting to believe that Kutab-ud-din-Aibak himself may have been buried here after his death from a polo accident at Lahore, though tradition says otherwise.

The great screen of arches which form the most striking feature of the mosque, like that at Ajmir, bears no proportion to the height of the arcades any more than the Kutab Minar does, but this is not really noticeable. It is not necessary to add anything to Mr Fergusson’s description of the screen and its beauties :—

“The glory of the mosque is not in these Hindu remains, but in the great range of arches on the western side, extending north and south for about 385 feet, and consisting of three greater and eight smaller arches; the central one 22 feet wide and 53 feet high; the larger side-arches 24 feet 4 inches, and about the same height as the central arch; the smaller arches, which are unfortunately much ruined, are about half these dimensions.

Behind this, at the distance of 32 feet, are the foundations of another wall; but only intended, apparently, to be carried as high as the roof of the Hindu pillars it encloses. It seems probable that the Hindu pillars between the two screens were the only part proposed to be roofed, since some of them are built into the back part of the great arches, and all above them is quite plain and smooth, without the least trace of any intention to construct a vault or roof of any sort. . . .” The arches, built by Hindu architects, are carried up in horizontal courses as far as possible, and are then closed by long slabs.

“The same architects,” Mr Fergusson continues, “were employed by their masters to ornament the faces of these arches; and this they did by copying and repeating the ornaments on the pillars and friezes on the opposite sides of the courts, covering the whole with a lacework of intricate and delicate carving, such as no other mosque, except that at Ajmir, ever received before or since, and which . . . is, without exception, the most exquisite specimen of its class known to exist anywhere.”

The details of the ornamentation deserve prolonged examination by the aid of fieldglasses. The bands of text in the Tughra character are particularly fine, and the graceful effect of them is much enhanced by the tendril pattern with flowers and bud, which is carried up through the lettering. A similar aid in a very different style of decoration is noticeable in the beautiful bands of texts of encaustic tiles upon a ground of sprays and leaves on the lovely Shahzindah tombs in Samarkand.

The difference in the decoration of the arches of Kutab-ud-din and Altamsh is considerable in detail, but this is not noticeable at a distance. The stone used in the former was of a much paler colour, and the ornamentation of the later arches does not seem to rise so spontaneously, or give so aspiring an effect to the facade, a difference which is no doubt accentuated by the panels of diaper work between them.

Of the pillars which carried the roof of the hall of the mosque in front of which the great screen was placed, two groups of twelve and ten alone remain. On one of the columns of the southern group is an inscription with the name of a Mutawali, or Guardian, which appears again beyond the first rounded shaft to the west of the door of the Kutab Minar, thus showing the two structures were of much the same date.

The additions made by the Sultan Altamsh to the original work of Kutab-ud-din, more than doubled the area enclosed by the mosque, and the extensions of Ala-ud-din would again have increased the dimensions to more than twofold, but it seems probable that, like the Alai Minar, these were never wholly completed, in spite of the high-flown admiration of them thus expressed by Amir Khusrau in his “Tarikh-i-Alai”:–

“He [the Emperor] determined upon adding to and completing the Masjid-i-Jama of Shamsuddin, by building beyond the three old gates and courts a fourth with lofty pillars . . . and upon the surface of the stones he engraved verses of the Koran in such a manner as could not be done even in wax, ascending so high that you would think the Koran was going up to heaven, and again descending in another line so low, you would think it was coming down from heaven.

He then resolved to make a pair to the lofty minar of the Jama Masjid, which minar was then the sole (unique) one of the time, and to raise it so high that it could not be exceeded. He first directed that the area of the square before the masjid should be increased, that there might be ample room for the followers of Islam. He ordered the circumference of the new minar to be made double that of the old one, and that it should be made higher in the same proportion, and he directed that a new casing and cupola should be added to the old one.”

The core of the piers of the arches in the further extension of the screen to the north designed by Ala-ud-din still stands, as do the ruins of the gates to the enlarged courtyard on this side; these gates would no doubt have been somewhat similar to the Alai Darwazah. In the middle of this extension to the north would have risen the Alai minaret, of which the stupendous base stands most probably just as the workmen left it on the death of its projector, nearly 600 years ago. It is fortunate, no doubt, that it was never finished, as it would have completely overshadowed and destroyed the effect of the original Kutab Minar, situated at the south-east angle of the original court of the mosque.

Writing of the mosque as a whole, Amir Khusrau says

“Masjid-i-o jármá’i feiz-i-Allah;

Zamzama-i-Khutba-i-o tába máh.”

(“The mosque of it is the depository of the grace of God ; The music of the prayer of it reaches to the sky [moon].”)

Ibn Batuta wrote of it: “Its mosque is very large, and in beauty and extent has no equal. Before the taking of Delhi it had been a Hindu temple. In its court there is a pillar which they say is composed of stones from seven quarries.”

The Hindus, it may be noted, still sometimes speak of the mosque as the Thakurdawara and Chausath Khambhe, or the Sixty-Pillared. The mosque was repaired by Firoz Shah Tughlak, as was the Kutab Minar— was the scene of a grim massacre by Tmiur’s soldiery,— and was immensely admired by that Sultan, who carried off workmen to construct a similar one in Samarkand which, however, was never built. A bloody slaughter had already taken place inside the mosque in the reign of Altamsh, when a body of Karmatian heretics, who had taken refuge there, were exterminated by volleys of stones from the roof of the arcades and mailed horsemen riding up the steps into the enclosure.

The Iron Pillar in the court of the mosque is one of the most interesting memorials of Hindu supremacy in all India, and dates probably from the sixth century of our era. The inscription upon which this conjecture is based consists of six lines of neat letters; the three couplets merely record the erection of the pillar to Vishnu, by one Chandra Raja. There are also brief inscriptions by the Tuar Anangpal II. and a Chauhan Raja, the former

commemorating a re-peopling of Delhi by the prince named in 1052 A.D. The pillar is 23 feet 8 inches high, and rests on a sort of gridiron arrangement under the platform from which it rises. It was long believed, on the authority of those who had made actual excavations, that it extended far below the surface of the ground, whereas the base is only 14 inches deep. The capital was no doubt once surmounted by a Garuda, the eagle vehicle of Vishnu, like the columns in front of the great temples of Jaggarnath at Puri.

The Hindu legend connected with the pillar is that it rested on the head of the great World Serpent, and that a Tuar prince having unadvisedly moved it to see if this was really the case, the curse fell upon him that his kingdom too should be removed.

Temple destruction, put in context

Manimugdha Sharma, December 11, 2020: The Times of India

From: Manimugdha Sharma, December 11, 2020: The Times of India

Plea on Qutub mosque: Historians slam taking history out of context

Manimugdha.Sharma@timesgroup.com

New Delhi:

Historian of Delhi Dr Swapna Liddle, who edited the English translation of the 19th century work, ‘Sair ul-Manazil’, expressed her dismay at this “never-ending, fruitless quest to right historical wrongs”. “Nobody denies the fact that temples were destroyed in a moment of war. But this was not because they were symbols of a rival faith but because they were symbols of power of the regime that was supplanted. That context is important,” Liddle said.

Liddle said the entire record needs to be looked at for anyone to have a proper understanding. “A grand Jain temple built by a minister of the Tomars, named Sahu Nattal, in 1132 was destroyed by the Ghurid army that conquered Delhi. That was possibly selectively chosen for its association with power. But other shrines nearby that enjoyed popular support, like the Dadabari Jain temple in Mehrauli and the Jogmaya Temple, were spared,” she pointed out.

Petitioners have claimed that 27 Hindu and Jain temples were destroyed and a mosque was erected in their place and named ‘Quwwat ul-Islam’ or ‘Might of Islam’, just to poke Hindus in the eye. This claim is based on the inscription put up at the mosque by Sultan Qutubuddin Aibak, which says that material from 27 temples was reused to construct the mosque. But historians once again advise caution.

“This name that carries a sense of bellicose hostility, however, was not the complex’s original one. Inscriptions on the mosque dating to the late 12th century call it simply a building (imarat) or mosque (masjid),” Prof Asher writes in ‘Delhi’s Qutb Complex: The Minar, Mosque and Mehrauli’.

Historian of the early Delhi Sultanate Minhaz us Siraj Juzjani describes Delhi in his Tabakat-i Nasiri as the Qubbat al-Islam. Since qubba means ‘refuge’ or ‘sanctuary’, historian Professor Sunil Kumar argues in his ‘The Emergence of the Delhi Sultanate’ that Juzjani’s use of the phrase referred to the role of Delhi as the sanctuary of Islam “at a time when the central Islamic lands were feeling the brunt of Mongol invasions”. “Qubba, however, also meant the centre, the axis, and in that sense, Qubbat al-Islam referred to the newly gained role of Delhi as the paramount power in north India, the centre of Islam,” Kumar writes.

At a later time, the term came to be used for the dargah of Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, argues Asher. This eventually got attached to the mosque as Quwwat ul-Islam. Both Mirza Sangin Beg’s 1820 work, Sair ul-Manazil, and Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s 1854 work, Asar us-Sanadid, refer to the mosque as Quwwat ul-Islam. But even in this, historian Professor David Lelyveld argues, the name didn’t have a militant sense.

“I agree with this view,” Liddle says. “It was just called the Jami masjid in its time.”

But what explains Hindu and Jain motifs in an Islamic building? Asher points out that the Ghaznavids and Ghurids had been employing Hindu artisans for a long time before their armies actually entered Delhi. So, there was a familiarity with Hindu imagery. Artefacts found in Ghazni point to that.

“You will find the lotus and the kalash at Muslim monuments. Look at Maulana Jamali’s tomb where above the mihrab, there is a kalash with Allah written on top of it. Take Gandhara art as an example. Today, we only see specimens of it in museums. But these Turkic people came from lands where Gandhara art was practised. Islam is a religion accepted by many different cultures. But architecture was cultural. They grew up in that culture, so they were familiar with it. Why can’t we understand that ?” Liddle said.

Mehrauli archæological park and Andheriya Morh

The Tomb of the Sultan Shams-ud-din Altamsh, behind the north-west corner of the mosque, is a very beautiful building of red sandstone, measuring forty-four feet square on the outside, and thirty feet square in the inside. The interior is profusely decorated with carving, only the lower portions of the wall in the two west angles, and to the right and left of the east door remaining uncarved.

These were covered with painting, a fragment of which—possibly a restored portion—may still be seen on the south wall; there are also traces of colour on the beautiful mihrab, or prayer niche, of the west wall. The grave itself is a handsome structure of unusual height and size, with a band of text round the plinth, which is also unusual. That the chamber was intended to be roofed is clear from the remains of the lowest course of a dome on the top of the south wall; but if it was built for her father by Sultan Raziya, as seems probable, it is quite possible that the dome was never completed.

Mr Fergusson writes of it:—

Though small, it is one of the richest examples of Hindu art applied to Muhammadan purposes that Old Delhi affords, and is extremely beautiful, though the builders still display a certain degree of ineptness in fitting the details to their new purposes. The effect at present is injured by the want of a roof, which, judging from appearance, was never completed, if ever commenced. In addition to the beauty of its details it is interesting as being the oldest tomb known to exist in India.

The Alai Darwazah is not only the most beautiful structure at the Kutab Minar, but is one of the most beautiful specimens of external polychromatic decoration not merely in India, but in the whole world, while the carving of the interior may challenge comparison with any work of the kind. Both exterior and interior merit detailed and leisurely examination. [1 Bishop Heber too recorded that the Kutab Minar was the finest tower he had ever seen.]

The effect of the graceful pointed arches in the three external sides of the gate, and in the corner recesses, is extremely pleasing, and the view from the exterior through the southern archway to the round-headed arch of the north side, and the courtyard beyond, is very striking. The decoration of the north arch is curious and unique.

The effect of the exterior suffers, from a distant point of view, from the absence of a parapet above the walls; this was unfortunately removed by Captain Smith, as it was greatly ruined. The gate was finished five years before the emperor died, and is specially mentioned by the chronicler of his reign. Of it Mr Fergusson writes :—

It is about a century more modern than the other buildings of the place, and displays the Pathan style at its period of greatest perfection, when the Hindu masons had learned to fit their exquisite style of decoration to the forms of their foreign masters. Its walls are decorated internally, with a diaper pattern of unrivalled excellence, and the mode in which the square is changed into an octagon is more simply elegant and appropriate than any other example I am acquainted with in India.

The pendentives accord perfectly with the pointed openings in the four other faces,1 and are in every respect appropriately constructive. True, there are defects. For instance, they are rather too plain for the elaborate diapering which covers the whole of the lower part of the building, both internally and externally; but ornament might easily have been added, and their plainness accords with the simplicity of the dome, which is indeed by no means worthy of the substructure. Not being pierced with windows, it seems as if the architect assumed that its plainness would not be detected in the gloom that in consequence prevails.

This building, though small—it is only fifty-six feet square externally, and with an internal apartment only thirty-four feet six inches in plan—marks the culminating point of the Pathan style in Delhi. Nothing so complete had been done before,2 nothing so ornate was attempted by them afterwards.

In the provinces wonderful buildings were erected between this period and the Moghal conquest, but in the capital their edifices 3 were more marked by solemn gloom and nakedness than by ornamentation or any of the higher graces of architectural art. Externally, it is a good deal damaged, but its effect is still equal to that of any building of its class in India.

On the east side of the Alai Gate is the sandstone and marble tomb of Imam Zamin, one Muhammad Ali, who died in 1539 A.D., and was probably connected with the Kuwat-ul- Islam Mosque. The decoration of this is decidedly effective; that on the dripstone is unusual. It makes an extremely pretty picture, as seen from the south side, in combination with the Alai Darwazah and the trees between the two.

The last building of the group directly connected with the Kutab Mosque and Minar is the B Tomb of Ala-ud-din. There is no reasonable doubt that this was in the centre of the three ruined rooms which form the south side of the enclosure behind the south end of the great screen of arches of the mosque. The chamber corresponds with the tomb of Altamsh, but is larger, being fifty feet by thirty-two feet.

The rooms at either side of this were also probably sepulchral chambers, while those in the wings to the front of it formed part of the college attached to the tomb. Behind the large rooms and part of the west wall is a long gallery which had its own entrance from the south; and in the south-east corner outside are the ruins of a mosque, from which a very fine view of the Kutab Minar and Alai Darwazah is obtained. It is fitting that the grave of this parricide should survive only as a lonely ruin, for the most part “unknown and unnoticed.” It was repaired by Firoz Shah, like so many other buildings, and as not a few of these were closely connected with the Kutab, the interesting record of his labours of love may be inserted here.

[1 As a matter of fact, the opening on the north side is rounded, and not pointed.]

[2 It was no doubt with reference to this and the decoration of the mosque screens and the Kutab Minar that Bishop Heber wrote: “These Pathans built lite giants and finished their work like jewellers,” though the words occur in immediate connection with the tomb of Adnam Khan.]

[3 This dictum of Mr Fergusson applies, no doubt, correctly to the buildings of the later severe Pathan styte, but hardly, for instance, to the tomb of Tughlak Shah (p. 289), or to those of Mubarik Shah and Sikandar Khan Lodi, or the gateway of the Khairpur Mosque (pp. 244 and 245).]

Among the gifts which God bestowed upon me, His humble servant, was a desire to erect public buildings. So I built many mosques and colleges and monasteries, that the learned and the elders, the devout and the holy, might worship God in these edifices, and aid the kind builder with their prayers.

The digging of canals, the planting of trees, and the endowing of buildings with lands are in accordance with the directions of the Law. The learned doctors of the Law of Islam have many troubles; of this there is no doubt. I settled allowances upon them in proportion to their necessary expenses, so that they might regularly receive the income. The details of this are fully set forth in the Wakf-Nama (Record of Charitable Assignments).

Again, by the guidance of God, I was led to repair and rebuild the edifices and structures of former kings and ancient nobles, which had fallen into decay from lapse of time; giving the restoration of these buildings the priority over my own building works. The Masjid-i-Jami of Old Delhi (i.e. the Kuwat-ut-Islam Mosque) which was built by Sultan Mu’izz-ud-din-Sam, had fallen into decay from old age, and needed repair and restoration. I so repaired it that it was quite renovated.

The western wall of the tomb of Sultan Mu’izz-ud-din-Sam,1 and the planks of the door, had become old and rotten. I restored this, and, in the place of the balcony, I furnished it with doors, arches, and ornaments of sandal-wood. [1 It is not easy to understand this reference to the tomb of Muizz-ud-din-Sam or Shahab-ud-din Ghori who was buried at Ghazni. Abul Fazl also refers to his grave in Old Delhi, but perhaps he merely followed Firoz Shah’s record in doing so.]

The Minara of Sultan Mu’izz-ud-din-Sam (i.e. the Kutab Minar) had been struck by lightning. I repaired it, and raised it higher than it was before. The Hauz-i-Shamsi, or tank of Altamsh had been deprived of water by some graceless men, who stopped up the channels of supply. I punished these incorrigible men severely, and re-opened the closed channels.

The Hauz-i’Alai, or tank of ’Ala-ud-din had no water in it, and was filled up. People carried on cultivation in it, and had dug wells, of which they sold the water. After a generation had passed I cleaned it out, so that this great tank might again be filled from year to year.

The Madrasa (college) of Sultan Shams-ud-din Altamsh had been destroyed. I rebuilt it, and furnished it with sandal-wood doors. The columns of the tomb, which had fallen down, I restored better than they had been before. When the tomb was built its court, 2 had not been made curved (? with arched arcades) but I now made it so. I enlarged the hewn-stone staircase of the dome, and I re-erected the fallen piers of the four towers. [2 This is not intelligible with reference to the existing tomb of this Emperor.

It might be held to be applicable to the mausoleum of Sultan Ghari which has columns in the grave chamber, corner towers to the enclosure, and steps up to the domed gate leading to this, and this mausoleum has all the appearance of having beer restored in the middle Pathan style of the severer type.] Tomb of Sultan Mu’izzud-ud-din, son of Sultan Shams-ud-din, which is situated in Malikpur. This had fallen into such ruin that the sepulchres were undistinguishable. I reerected the dome, the terrace, and the enclosure wall. Tomb of Sultan Rukn-ud-din, son of Shams-ud-din, in Malikpur. I repaired the enclosure wall, built a new dome, and erected a monastery (Khangah), (p. 285). Tomb of Sultan Jalal-ud-din (Khilji— it has disappeared.) This I repaired, and I supplied it with new doors.

Tomb of Sultan Ala-ud-din. I repaired this, and furnished it with sandal-wood doors. I repaired the wall of the abdarkhana, and the west wall of the mosque, which is within the college, and I also made good the tessellated pavement.

Tomb of Sultan Kutab-ud-din and the (other) sons of Sultan Ala-ud-din, viz., Khizr Khan, Shadi Khan, Farid Khan, Sultan Shahab-ud-din, Sikandar Khan, Muhammad Khan, Usman Khan, and his grandsons, and the sons of his grandsons. The tombs of these I repaired and renovated. (All these have disappeared.’)

I also repaired the doors of the dome, and the lattice-work of the tomb of Shekh-ul-Islam Nizam-ul-hak-wa-ud-din, which were made of sandal-wood. I hung up the golden chandeliers with chains of gold in the four recesses of the dome, and I built a meeting-room, for before this there was none.

Tomb of Malik Taj-ul-Mulk Káfur, the great wazir of Sultan Ala-ud-din. He was a most wise and intelligent minister, and acquired many countries, on which the horses of former sovereigns had never placed their hoofs, and he caused the Khutba of Sultan Ala-ud-din to be repeated there. He had 52,000 horsemen. His grave had been levelled with the ground, and his tomb laid low.

I caused his tomb to be entirely renewed, for he was a devoted and faithful subject.1 [1 It would seem certain from this that the tales of Muhammadan annalists to the effect that Malik Kafar poisoned his master Ala-ud-din, and set himself up as king and was murdered, cannot be true. It is incredible that Firoz Shah could have written thus of him if they were. The grave has disappeared again.] The Dar-ul-aman, or House of Refuge,—This is the bed and resting - place of great men (i.e. the Sultan Balban and his son, the Khan-i-Shahid (p. 278). I had new sandal-wood doors made for it, and over the tombs of these distinguished men I had curtains and hangings suspended.

The expense of repairing and renewing these tombs and colleges was provided from their ancient endowments. In those cases where no income had been settled on these foundations in former times for providing carpets, lights, and furniture for the use of travellers and pilgrims in the least of these places, I had villages assigned to them, the revenues of which would suffice for their expenditure in perpetuity.

Jahan-panah.—This foundation of the late Sultan Muhammad Shah, my kind patron, by whose bounty I was reared and educated, I restored.

All the fortifications which had been built by former sovereigns at Delhi I repaired. For the benefit of travellers and pilgrims resorting to the tombs of illustrious kings and celebrated saints, and for providing the things necessary in these holy places, I confirmed and gave effect to the grants of villages, lands, and other endowments which had been conferred upon them in olden times. In those cases where no endowment or provision had been settled, I made an endowment, so that these establishments might for ever be secure of an income, to afford comfort to travellers and wayfarers, to holy men and learned men. May they remember those ancient benefactors and me in their prayers.

I was enabled by God’s help to build a Dar-ush-shafa, or Hospital, for the benefit of every one of high or low degree, who was suddenly attacked by illness and overcome by suffering. Physicians attend there to ascertain the disease, to look after the cure, to regulate the diet, and to administer medicine. The cost of the medicines and the food is defrayed from my endowments. All sick persons, residents and travellers, gentle and simple, bond and free, resort thither; their maladies are treated, and, under God’s blessing, they are cured.

Under the guidance of the Almighty I arranged that the heirs of those persons who had been slain in the reign of my late lord and patron, Sultan Muhammad Shah, and those who had been deprived of a limb, nose, eye, hand, or foot, should be reconciled to the late Sultan and be appeased with giftst so that they executed deeds declaring their satisfaction, duly attested by witnesses. These deeds were put into a chest, which was placed in the Dar-ulaman (i.e. the tomb at Tughlakabad, not that of the Sultan Balban), at the head of the grave of the late Sultan, in the hope that God, in His great clemency, would show mercy to my late friend and patron, and make those persons feel reconciled to him.

It may be noted here that, like Timur, the Emperor Baber visited the principal buildings round Delhi after his victory at Panipat, whence he made three marches to Nizam-ud-din. “I circumambulated,” he writes, “the tomb of Khwaja Kutab-ud-din, and visited the tomb and palaces of Gheias-ud-din Balban,2 of Alaud-din Khilji anct his minaret (the Kutab Minar), the Shamsi Tank, the Royal Tank (Hauz Alai) and the tombs and gardens of Sultan Bahlol and Sultan Sikandar; after which I returned to camp and went on board a boat where we drunk arak (!)” The next day the Emperor marched to Tughlakabad, and so on to Agra. [2 It would seem probable that this was the tomb of Shams-ud-dim Altamsh, and that the Emperor was misinformed or forgot. It seems hardly possible that if Balban’s tomb was complete in 1526, it should now be the utter ruin that it is.]

A number of interesting buildings surround the enclosure of the Kutab Minar, but probably few visitors will have time to examine them. The Jamali Mosque, and for the sake of the memory of a great man, the ruined tomb of the Sultan Gheias-ud-din Balban near it, and the Dargah of the Kutab Sahib should, however, certainly be visited.

The first two are reached by the road running south from the east side of the enclosure past a converted tomb known as Metcalfe House. This stands on the wall of the Lal Kot, and was the resting-place of one Muhammad Kuli Khan, brother of Adham Khan, and therefore foster-brother of the Emperor Akbar and must once have been brilliantly decorated with painting.

The Jamali Mosque, which lies five hundred yards south of this, is a fine and pleasing structure of the date of 1528 A.D.: it forms an intermediate stage between the Moth-ki Masjid (p. 245) and that of Sher Shah in the Purana Kila and has been well restored by Government. The picturesque grave chamber of Jamali, Shekh Fazl-ullah, stands on the north side of the courtyard of the mosque.

Rising high up amid ruins, 200 yards east of the two, are the massive walls which once carried the tomb of the Sultan Balban, who died in 1287 A.D. (p. 296). This was a square building, like the tomb of Altamsh and the Alai Darwazah, but was larger than either of these

- on each side of it is a spacious room, which may have formed the Dar-ul-aman, or Haven of

Refuge, established by this king.

He was buried in that place—Ibn Batuta says he visited his grave in it—where his son Sher Khan, the Khan-i-Shahid, was interred only two years before him. This prince was slain at Lahore fighting against “Sámar, the bravest dog of all the dogs of Chengiz Khan,” and the father never recovered from the loss of the son. The Dargah of the Kutab Sahib is most conveniently approached from the west side, but can also be entered from the north.

The high road from the Kutab Minar enclosure leads to it past the Tomb of Adham Khan, which, owing to its being placed on the wall of the Lal Kot citadel, is so conspicuous a feature in all distant views of the Kutab. The tomb, though of so late a date as 1566 A.D., is built entirely in the severe middle Pathan style, and the materials of it were quite possibly taken bodiiy from some Pathan tomb; the domed interior is very fine, and many beautiful views of the Kutab Minar may be enjoyed from the arcade round the exterior, in which the stone over the grave of Adham Khan has been placed.

That of his mother, who is said to have died of grief forty days after the righteous execution of her son, has disappeared. Sympathy with either would be wholly wasted. The story of Adham Khan has been already told and no one who has visited the beautiful old fortress of Mandu and entered the charming pavilion of Rupmati, on the edge of the sheer side of the tableland which overlooks the broad Nerbuddah, will feel anything but satisfaction that such a fate as his was should have overtaken him.

Adham Khan had wrested Mandu from the last of the Gujerat kings, and having obtained possession of his beautiful mistress, sought to compel her to yield to his desires, upon which, Lucretia-like, she killed herself. When the Emperor Akbar heard of this he recalled and disgraced Adham Khan, though he was his half-brother as well as his foster-brother, and demanded the surrender of two ladies of the family of the defeated king, whom also Adham Khan had captured. They were accordingly sent to the royal court, and there they were poisoned by Maham Anagah, the mother of Adham Khan, to prevent their making any complaint to the emperor.

A hundred yards to the south-east of this tomb is a fine baoli, known as the Gandak Baoli, in which old Jain columns have been used. Divers jump into this tank also. Three hundred yards further east of it, and among the ruins of many graveyards, is a still finer baoli of the date of 1516 A.D., known as the Rajon-ki-Báin, with a picturesque tomb and mosque on the west side of it. The details here show again how considerable a reversion to the Hindu style took place in the Lodi period.

The Shrine of Khwaja Kutab-ud-din Bakhtiar Kaki, known also as Kutab-ul-Aktúb, once the most famous at Delhi, now occupies only the second place, a circumstance doubtless due to the fact that the Dargah of Nizam-ud-din-Aulia was more conveniently situated for resort from the various cities which succeeded and superseded the original Delhi.

This saint was born at Ush, not the once famous place in Sind, but a still older one in Farghana (Turkestan), and came to Delhi with the earliest Muhammadan conquerors — perhaps even before them—and died there in 1235 A.D., in the reign of the Sultan Altamsh. His title of Kaki is derived from the tradition chat during his fits of abstraction (chihal, or forty days—the traditional scene of the fasts of St John the Baptist, near Jericho, is still called Quarantina), he was fed by the saint known as the Khizr, with small cakes, termed kak.1 [1 Local pride in the saint converts this into a story that on one occasion these cakes were lowered from Heaven amid an assembly of holy men, at the Aulia Mosque (p. 284), but that only Kutab-ud-din was permitted to take them.] In Ferishta’s time these cakes were still cooked and given to tbe poor; now they are prepared and presented to wealthy visitors to the shrine in return for their offerings. They are small, thick, round cakes, made of flour, sugar, and sonf (anise seed).

Outside the Dargah, on the approach from the west, is a mansion and high-standing mosque belonging to the well-known physician Ahsanulla Khan, who was chief adviser of the last king of Delhi, Bahadur Shah, and whose evidence at the king’s trial is extremely interesting, Beyond it is a fine gateway leading to the building, known as the Mahal Sarai, which was occupied as a summer residence by several of the latest kings of Delhi, a circumstance which no doubt led to their being buried at the shrine of the Mahrauli saint. Passing through the outer gate of the western enclosure of the Dargah, of which a plan accompanies, we enter a courtyard with a mosque and the grave of Murad Bakht, a lady of Shah Alam II., on the left side, and the Moti Masjid, and the tombs of the last kings of Delhi on the right side. The mosque was built by Shah Alam Bahadur Shah, successor of Aurangzeb, in 1709, and is pretty but feeble.

At the corners of the wall facing it are two detached minarets, The three royal graves in the little court to the south side of the mosque lie within a simple marble enclosure—that on the east is the resting-place of Akbar Shah II. (died 1837 A.D.), the next to it is that of Shah Alam II. (died 1806), then beyond an empty space, intended for the grave of Bahadur Shah, buried at Rangoon, comes the tomb of Shah Alam Bahadur Shah, a plain stone with grass on it. The furthest grave to the west is that of Mirza Fakhru, heir apparent of the Bahadur Shah, whose murder led in part to the palace intrigues which added one more cause to the many others that led to the mutiny of 1857.

An inner gate now conducts to the courtyard on the north side of the shrine, with the grave of Mohtamid Khan, Annalist of Aurangzeb, and a mosque on the left; while on the right a paved way with marble walls and a marble gate at the end leads past the enclosure of the saint’s grave to the southeastern court. Visitors entering the grave enclosure by the marble gateway on the south side of it are expected to take off their shoes. As a matter of fact, all that is of interest in it can be seen through the handsome pierced marble screens of the east and south wall, erected by the Emperor Farukhsiyar. The grave is a plain earthen mound, covered by a cloth and surrounded by a low marble railing.

A canopy is suspended over it from four marble columns in the court. A number of other graves lie round it. “Many other servants of God,” writes Abul Fazl, “instructed in divine knowledge, in this spot repose in their last sleep.” The west wall of the enclosure is decorated by tiles of green and yellow in alternate rows. This work is indifferently ascribed to Shekh Farid-ud-din Shakarganj who came to Delhi upon the death of his master, and to Aurangzeb. Probably the former built the wall as a place for prayer, and the latter added the decoration.

Outside the south-cast corner of the enclosure is the mosque of the Khwaja Kutabuddin, much renovated and added to since his time. Under the shadow of it is the grave of Maulana Fakhruddin, who built the gate at the end of the marble way, and in front of it is the grave of a lady known as the Daiji, on the edge of the tank. (A tank seems to have been a special feature of the Chisti shrines. Visitors to Ajmir will remember the very deep one excavated in the rock under the face of the mountain at the Dargah of Muin-ud-din Chisti, and that of Nizam-ud-din Aulia has already been specially mentioned).

This is a fine structure, but unfortunately does not retain the water which comes into it. At the head of the tank is the grave of Zabita Khan, the Rohilla, in front of an assembly hall built by him. The second grave alongside of it is declared by the Khadims of the shrine to be that of Ghulam Kadir Khan.

This is not impossible—the tombstone is that of a woman, but there are various instances of such stones being used for the grave of a man—but is not very probable, as Ghulam Kadir was put to death by the gradual amputation of limb after limb, and his body remained exposed for some time before it was secretly removed, and it is likely therefore to have been buried both secretly and hurriedly. The superstitious chronicler of the day records that while the corpse hung from a tree head downwards, “a black dog with white round the eyes came and licked up the blood as it dropped. The spectators threw clods and stones at it, but it still kept there. On the third day the corpse disappeared, and the dog also vanished.”

From the head of the tank is obtained a very effective view of the Kutab Minar. In the north-west corner of this southern court is the graveyard of the Nawabs of Loharu, and outside the north court and gate is that of the Nawabs of Jhajjar, two ruling families created by Lord Lake after 1803, of which the latter disappeared after the events of 1857. Some distance beyond the inner gate on the north side is another outer gate with Hindu details, built in the time of Sher Shah, who, with Salim Shah, was a special patron of this shrine. The unfinished large Music Gallery or Naubat Khana, on this side also belongs to that period.

The lesser known tombs

Richi Verma, Hidden history emerges from these tombs, Jan 3, 2017: The Times of India

Dozens of unprotected monuments at Mehrauli Archaelogical Park in south Delhi are fading away .

Conservation exercises by the Delhi government have helped archaeologists to dig out newer facts about the Lodhi and Mughal dynasties to which these building belong. A case in point is the ongoing conservation project on two tombs and the ruins of a horse stable inside the park where conservationists have discovered that the actual height of the monuments was much more than what's visible now--there are hidden chambers.

However, unlike the ASI protected monuments like Rajon ki Baoli and Jamal Kamali, which have enough archival documents and photos, other non-ASI monuments don't have enough archival details. “These monuments have been documented through heritage listings but very little information is available on them, like their actual height and who the graves belong to,“ said an official.

An unknown tomb, another with a jharokha and a horse stable are adjacent to a nullah that runs through the park. “During the rains, a lot of malba used to collect at the foot of the two tombs, which just kept collecting over the years. Eventually , we realised while clearing the surrounding area that the actual height was much more,“ said an Intach Delhi chapter official.Intach has collaborated with the Delhi government's archaeology department to conserve these three buildings.

At least four feet more of the tombs have been found.“Once we started clearing the debris, we found hidden chambers and even a few graves for the first time. Work is still on at the two tombs and we might find more graves, chambers or inscriptions,“ the official said, adding, “In one tomb, we found a plinth we never knew existed.“

Many experts earlier disputed that the horse stable indeed housed horses as it was not big enough. Digging unearthed nearly six feet more of the structure. “This showed that the height of the stables was much more than previously thought. It remains to be seen what more new things are discovered during the conservation exercise,“ said another official.

Work has been on for three months, with another three months to go. Nineteen buildings have been identified for conservation as part of this collaboration.

2017: Encroachments, issues

Almost a thousand years of India's history lies inside the 100 acres that is the Mehrauli Archaeological Park. Almost as if claiming a niche in that story, modern Delhi is making inroads into the conservation area, in the process putting at risk not only the 127 heritage structures there, including the six protected by the Archaeological Survey of India, but also the historical character of the park.

The clearest signs of encroachment are the illegal buildings in the proximity of many of the monuments.It was this encroachment that made Intach file a petition in Delhi high court in 2015, in response to which the court directed Delhi Development Authority, the owner of the land, to take appropriate steps to demarcate the archaeological park and prevent encroachments.

But incursions have continued. Often, it is the unnamed and unidentified monuments that bear the brunt of neglect. “Recently, Intach took steps to preserve an unnamed tomb in the park, but before anyone could prevent it a madrasa had come up there,“ related a senior conservationist. “The people first erected a shed and in a matter of weeks had taken over a big tract of land for their complex.“

A cleric from the madrasa insisted to TOI that the school had existed there “for more than four years and we teach 27 students“.“It is a legal structure and we have all the permissions,“ the cleric claimed.

Convenor Swapna Liddle said out that Intach had been worried about the problems for a number of years now. Its 2015 PIL was aimed at ensuring not only proper maintenance and preservation of the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, but also the prevention of further decay and destruction of historical artefacts.And yet take the case of the late-Lodhi period horse stables. Just a month ago, even as Intach is renovating the structure, an il legal toilet came up along the monument's wall, next to a small mosque, which, according to its caretaker, “has been around since Mughal days“.

Along with encroachments, littering has become a big problem too. Part of the problem is because DDA has not made strenuous efforts to clarify the expanse of the historical area. “A committee was formed, as directed by the high court, with members from all stakeholder agencies to chart out a plan for the park and to make it better,“ said an Intach official.

In his response to queries by TOI, a senior DDA official claimed the “demarcation process has begun“.He said, “We have asked for tenders to build the boundary walls and have earmarked the 300-metre stretch on which the wall will come up, other than in the western area. The work will begin this month.“

While not as well known to tourists as the neighbouring Qutub Minar complex, there still is popular interest in the park. The need now is for the authorities to take an interest in keeping it alive.

Town of Mahrauli

The little town of Mahrauli is situated on the east side of the Hauz Shamsi, constructed by the Emperor Altamsh. This must once have been a very fine reservoir, but it seldom contains much water now.

The view of the tank with buildings and gardens round it is, however, very picturesque. Among those on the east side are a fine structure of red sandstone, known as the Jehaz, or Ship, consisting of a courtyard of much later date added to an earlier mosque, and the Aulia Masjid, a simple enclosure marked by a very fine bor tree, where, according to tradition, prayers of thanksgiving for the capture of Delhi were offered up in 1191 A.D. Near this, on the opposite side of the road, the water of an escape channel from the tank falls picturesquely down to the Jhirna Garden with some very fine trees, and passes on towards Tughlakabad.

Mahrauli is much resorted to by the people of Delhi after the summer rains have set in, and the Pankah Mela, or Fan Fair, held there, is one of the principal popular festivals of the countryside. Near the north-west angle of the bazar, where there is a tomb of a third brother of Adham Khan, a country road leads to the village of Malakpur, three miles west of Mahrauli and the tomb known as Sultan Ghari.

This is the resting-place of Nasr-uddin Mahmud Shah, known as Abul Fatah Muhammad, eldest son of Sultan Altamsh, who, like the sons of Sultan Balban and Firoz Shah Tughlak, died before his father in 1228 A.D., and well deserves a visit. It is situated in the centre of a stone enclosure raised high above the ground, which, with its sloping corner towers, seems to have been a forerunner of the mosques in the severe Pathan style, if indeed it was not restored in that style (see note The picturesque gateway is constructed in the same manner as the screen arches at the Kutab Mosque.

The marble tomb chamber itself is mainly underground, only the roof and the walls which support it appearing above the level of the platform, and is approached by a steep flight of narrow steps. From this peculiar arrangement the name of the mausoleum (Ghár = cave) is derived.

The roof is borne by stone beams arranged as in mosques made up from Jain materials. The inscription on the gate gives to the son the title of Malik-i-Maluk-ush-Sharak, Lord of the Eastern countries, as he died while Governor of Lakhnauti, the modern Dacca. At the south-cast angle of the enclosure on the outside were two fine domed canopies over the graves of Sultans Rukn-ud-din and Muiz-ud-din, also sons and short-lived successors of Altamsh; but one of these has fallen, and the other will fall unless it is speedily secured. In front of the mausoleum are various buildings of the severe middle Pathan style, Including a fine mosque.

Five miles due east of the Kutab stand the grand ruins of the Fortress and City of Tughlakabad and the noble tomb in which Tughlak Shah and his son and murderer lie buried.1 The road descends almost at once from the wall of Lal Kot, and in less than a mile passes through the long earthen mounds which mark the eastern defences of Kila Rai Pithora. [1 Every one who possibly can, should see these. There are few great ruins or buildings in the world which I have not seen, and I recommend a visit to these advisedly.—H. C. F.]

Hauz Rani

Near this point on the north side of the road are the ruins of an old bridge which led to the Budaon Gate of the city, frequently mentioned in the annals of the time, and half a mile away on the same side are the grove which marks the Hauz Rani, or Queen’s Tank, and the village of Khirki, the dark walls of whose mosque can be seen in the trees.

Civic issues

2017

Paras Singh, In Mehrauli, ruins & rubbish abound, April 15, 2017: The Times of India

Mehrauli once was the capital of the Delhi sultans. It was named after the Persian words `mehr' and `auliya', meaning `grace of the saint'. In the last five years, though, civic authorities have been anything but graceful towards this area.

An important place in terms of heritage, Mehrauli has several medieval ruins dating as early as the 11th century when the Tomars ruled Delhi.But the most famous heritage building here is the world heritage site of Qutub Minar. Naturally , it registers a heavy footfall of tourists, Indian and foreign alike. But encroachments and unauthorised constructions have eroded Mehrauli's charm. Delimitation has also massively changed the contours of this area. Mehrauli had four wards earlier; this time, though, it would send only three councillors to the south corporation from Lado Sarai, Mehrauli and Vasant Kunj as the Kishangarh ward has been merged with Mehrauli.

The sitting councillors rue that haphazardly done geographical redistribution of localities has made administration even more difficult. “Not only has the geographical area has increased, but now, even travelling within the ward will become difficult. Our ward has Saket at one end and Kusumpur on the other with a distance of 12 km. With limited funds, the new councillors will find it difficult to manage these areas“ said Anita Chaudhary the current corporator from Lado sarai.

Haphazard growth has turned the urbanised villages like Lado Sarai, Ber Sarai and Katwaria Sarai into rent havens.The four to five storied buildings and narrow lanes house a large number of tenants, most of them students and company workers, putting the existing civic infrastructure under tremendous pressure.Hari Singh (60) from Katwaria Sarai said, “Sewage has created an acute sanitation crisis.The lanes get frequently , leading to mosquito breeding. No wonder we had so many chikungunya cases last year.“

Chaudhary argued, “The sewerage system was installed 30 years ago when six to seven people lived in a house. But now the multi-storey buildings have 50-60 people.“

Begum Zakiya (35) of Mehrauli said street cleaning is in frequent and the tourist load adds to the garbage. Heritage baolis have become dumping yards.

Although not under the purview of the corporation, the area also suffers from water crisis. Underground water is unusable, and a parallel water economy and supply of drinking water from a bottling plant has cropped up. Kishangarh resident Ramesh Chandra (58) said people are forced to pay Rs 2,000 for water tankers.

Once dotted with sarais or inns, the area now has many farmhouses belonging to the rich. These house parties, weddings etc and result in a traffic nightmare.

Vasant Kunj and Saket have good infrastructure, but have a massing parking problem. The local councillor, though, says the corporation can't help as it doesn't own land.

Slum clusters in Kusumpur Pahadi and Motilal Nehru Camp have terrible drainage with the only big drain choked.Councillors say they can't spend on these areas as the ex isting rules bar them. Vasant Kunj's Congress councillor, Om Wati, said it was because of “step-motherly treatment by BJP“. She said, “Almost half of the area's safai karamcharis were removed. I have been able to create community centres, meeting halls, public toilets and herbal parks in Ber Sarai and Mehsudpur.“

Neelgo Masjid

2019: encroachments

Manimughda Sharma, Dec 6, 2019 Times of India

From: Manimughda Sharma, Dec 6, 2019 Times of India

From: Manimughda Sharma, Dec 6, 2019 Times of India

A Sultanate-era mosque in Mehrauli has become a cause of much anguish for the locals after a land-grabber occupied the structure and allegedly razed parts of the building. The building, which conservationists think came up in the Lodhi period, is less than 10 metres from the Lodhiera Jahaz Mahal, which is a centrally protected monument. And although it has no known name in the records, locals call it the Neelgo Masjid.

TOI visited the spot on Tuesday and found “bouncers” guarding the structure. They didn’t allow anyone to go near the place or click photographs. Entreaties with people who live in buildings adjacent to the spot to let us click photographs from their rooftops didn’t yield positive results either as nobody wanted to earn the wrath of the “land mafia”.

Eventually, our photographer had to climb atop Jahaz Mahal to manoeuvre for a shot. And the violation was apparent. Huge, blue-coloured tin sheets have been installed as barricade around the site so that nobody can enter or even see what is going on inside. The lone opening there has been blocked with a truck. Since the building falls in the prohibited zone (100-metre radius), any construction or demolition there is illegal.

Incidentally, it was being conserved by Delhi government’s archaeology department until an NGT ban on constructions kicked in two months ago. The mosque was then occupied and barricaded on November 26, locals said. Qari Muhammad Hassan, who claims to be the imam of the mosque, said goons arrived there and pushed him out of the mosque. “Ye kuch dinon se koshish kar rahe thhe ki masjid shahid kar di jaye (they had been trying for sometime to raze the mosque),” Hassan alleged.

Others said there was an ownership dispute over the plot of land where the mosque stands. “The land is owned by DDA, but there has been a dispute over its ownership for a while. The Supreme Court ordered to maintain status quo there sometime ago. We included the monument in the list for conservation and had been working there when the NGT ban on constructions kicked in. And now, this has happened. How can anyone put up those tin barricades with a court-ordered status quo in place and the building falling in the prohibited zone of ASI? We have written letters to all authorities concerned, including the police. Action is awaited,” said Vikas Maloo, head of the department of archaeology, Delhi government.

Maloo also rejected the claim made by a few locals that namaz was offered in the mosque until 2009. “I am not aware of any such thing. It was a barren structure when we picked it up for conservation,” he said. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), while refusing to confirm if it has lodged an FIR, said it has explored all legal means. “ASI Delhi circle is handling this. The circle officers have been tasked with preparing a detailed ground report on this,” said an ASI official.

Parvez Alam Khan, president of Okhla Block Congress Committee, said the entire plot measures about an acre. “People were happy when the state archaeology department conserved the adjacent Jharna (a Mughal pleasure garden built in 1700). The mosque was the next in their list for conservation. In fact, they had started the work when their work was obstructed. You could still see the material brought for the work lying abandoned inside,” he said.

An Intach official agreed with some of the points made by Parvez Alam. “We were chased around by people when we worked there. So, we can understand when you say that you were obstructed. The idea was to develop the entire area from the Jharna to Jahaz Mahal as an integrated heritage complex. Tourists could start with the Jharna, then visit the mosque, and step out of it to enter the Jahaz Mahal and go all the way to Hauz-i-Shamsi. The Delhi government liked the plan and they included the mosque in the list. As we began work, the NGT ban came into force in October and we had to stop,” the official said.

Parvez Muhammad, a retired engineer, showed video clips purportedly showing workers razing portions of the mosque. “I am amazed this can happen under the nose of so many different agencies,” he said.

Another local said on the condition of anonymity that the land-grabber intends to build residential flats and a commercial complex on the plot. However, TOI could not independently verify those claims.

But the Intach official stressed that the Delhi government needs to act aggressively. “If there is a land dispute, fix it. If you have to compensate people, do it. But get the building back and conserve it. It’s a Sultanate period building. You cannot let it go waste,” he said, adding that a Japanese delegation had documented this building as part of an official visit in the 1950s.

Delhi Waqf Board claims ownership of the mosque. Its chairman Amanatullah Khan confirmed to TOI that the mosque has been illegally occupied. “We have now obtained a stay order from court,” Khan said. He said he would provide a copy of the stay order with this correspondent but hadn’t done so till the time of filing of this report. “It is the police’s fault,” Khan alleged.