Delhi: Najafgarh

Contents |

Crime

2016

The Hindu, January 25, 2016

Shiv Sunny

Gangsters are legends in this village

Elders of the notorious Mitraon village in Najafgarh rue the loss of a generation to violence.

If anyone ever suggests ‘Fauzi’ or ‘Balraj’ during the naming ceremony of a child in this village, they draw scornful and warning stares. But these are the very names many children demand to be rechristened with when they breach their teens.

Welcome to Mitraon village in Najafgarh area in South West Delhi whose younger generation idolises gangsters like Fauzi and Balraj — they are nothing less than “legends” for the teenagers here.

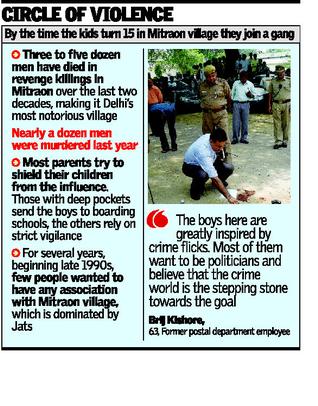

As per various estimates, three to five dozen men have died in revenge killings in Mitraon over the last two decades, making it arguably Delhi’s most notorious village. Since the start of last year, when four villagers were found charred in a car, around a dozen men have already been murdered.

It all began over a few acres of land in the 1990s. Today, this village has produced some of the most notorious gangsters like Manjeet Mahal, Naveen Khati and Ravinder Bholu.

“Today, the rivalries are no more just over property or money. It is now over a false sense of honour,” says Dependra Pathak, Joint Commissioner of Police (South-Western Range).

The younger lot in this village are inspired by Indian films that show orphans rising from railway tracks to rule over the underworld. They want to imitate gangsters who arrive at the village in suave SUVs with bodyguards flanking them.

Most parents do all they can to shield their children from the influence. Those with deep pockets send the boys away to boarding schools outside Delhi at the first opportunity.

The less fortunate ones rely on strict vigilance. They allow their children to interact with very few friends and track their movements closely.

“There are times when I have paid surprise visits to his school and even secretly followed him by another vehicle to know which places he visits and whom he interacts with,” says Sandeep Gehlot, father to a 16-year-old boy.

For several years Mr. Gehlot kept the TV remote with him. “I allowed my son to watch only children’s shows like Chhota Bheem and Motu-Patlu. He was never allowed to watch gangster films,” says Mr Gehlot, a farmer.

Sandeep is not alone when it comes to monitoring what children watch on TV. “The boys here are greatly inspired by crime flicks. Most of them want to be politicians at a later stage in life and believe that the crime world is the stepping stone towards the goal,” says Brij Kishore, a 63-year-old ex-employee with the postal department.

By the time the children turn 15, they are associated with one of the several small gangs from the village. Once the gang leader is arrested or killed, they see an opportunity to break away and form their own gang.

Even after severe crackdown on the gangs in the past, there are 15-20 small and big gangs operating from the village. A murder here is followed by another and the revenge cycle goes on.

All this takes its toll on the youth, particularly girls, when they reach marriageable age. For several years, beginning late 1990s, few people wanted to have any association with Mitraon village, which is dominated by Jats.

“Many members of our younger generation were unable to find brides or grooms because of fears of early widowhood or getting into legal troubles. The only thing residents of other villages discussed about Mitraon were the gang-wars. It became embarrassing for us to visit another village,” says Om Krishan, a local.

Despite no dip in the crime scene, the marriage situation has improved claim villagers. Yet, it took a retired government teacher of the village two years before he could find a groom for his daughter who was by then “way past her marriageable age”.

“My daughter is a government school teacher and under normal conditions she would have found enough suitors,” says the teacher, insisting that he faced this hurdle despite no one from his family being ever associated with any gang.

The older generation claims to have done their bit to end the rivalries between residents of the around 12,000-strong village. Village elders say they attend weddings at each others’ homes even as their sons and grandsons are warring against one another. But this has had little impact as the young criminal elements show scant regards for their elders. “Even at this age I am scared to smoke in front of my father. But the younger members do not care to even hide their guns when they come home,” says the school teacher.

Amid all this, police have been holding regular meetings with the village heads to keep the youngsters in check, but the ground reality is that they know that a round-the-clock deployment of a good number of police personnel in and around this village is the only way to prevent violence here.

Heritage, havelis

As in 2021

Mohammad Ibrar, February 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Mohammad Ibrar, February 13, 2021: The Times of India

Just past Delhi Gate, you come to a haveli with a stone doorway adorned with intricate floral patterns. Inside, a teak doorway leads to a large courtyard where a nearly centuryold charpoy and an heirloom brass pot catch the attention. The traditional house could pass off for any well-preserved haveli of old Delhi. Gopi Singhal, the owner, is a cloth merchant and has spent many years conserving this ancestral haveli in Najafgarh in southwest Delhi.

Yes, Delhi Gate and havelis recall the lingering old-world charm of old Delhi. But Najafgarh, unknown to most people, is also a hub of havelis. Unfortunately, the town which bears the name of Mughal official Mirza Najaf Khan, is burdened now with burgeoning modernity and slowly losing its heritage character. Perhaps the most striking example of this time-eroded legacy is Delhi Gate. The words on the top of the structure now call it the Vad Kishan Lal Duar. The old gateway is so completely revamped that it looks like a contemporary construction. Sudheer, who runs a book store opposite the gate, recalled its renovation by a local politician two decades ago. “Some people call it Delhi Gate, but most of us know it by its new name,” he shrugged.

The gate, which has a plaque to commemorate the martyrs of World War I, is covered with tiles now. Suraj Kumar, senior conservator at Intach’s Delhi Chapter, rued that far removed from public consciousness, there was nobody to prevent the gateway’s shabby treatment. “Remnants of its old self are visible in the quartzite stone base and the Mughal-favoured Lakhori bricks interior, discernible at the spots where the tiles have fallen,” Kumar pointed out.

Past the gate and the statue of Jawaharlal Nehru lie several havelis. Many of these, such as the old haveli adjacent to an Arya Samaj Mandir, have just the Lakhori brick exterior surviving, the thin, flat red bricks proving their Mughal provenance. This is where Singhal’s haveli stands. “My home is 150 years old and is still stronger than most new houses,” said the 49-year-old cloth merchant, who claimed that his grandfather was often called up for jury duty in British courts prior to independence. Singhal remembers how people mocked him when he decided to conserve the old haveli. “They advised me to spend my money on a modern house instead,” he said. However, he realises that he might not have followed heritage norms during the renovation. “If we had got government support, we would have adopted scientific modes of conservation,” he admitted.

Najafgarh’s havelis now lie hidden behind shops and hoardings, some of them modified beyond recognition. Ashok Saini, owner of Sri Deshraj Jagdish Prasad Sweet Shop at the Old Anaj Mandi, claims that the road had havelis on either side. Few have survived. “The change began over 30 years ago,” said Saini, whose family has run the confectionary shop since 1880. “People left the rustic Najafgarh and settled in the city. No one bothered about their ancestral properties. In any case, people weren’t aware of the importance of preserving heritage houses. Neither did the government support them.”

Nearby, masons worked busily at a nameless haveli that Girish Jain, a Najafgarh businessman, bought in January. “I wanted to shift to a bigger place, so I bought this haveli. I have no idea how old the structure is,” said Jain. His wife, Sarika, informed that the haveli had three floors and a large terrace. “We are getting the place repaired. We are not touching the gate of the haveli because it is so very pretty,” she said. At Mitraon village too, a few kilometres from Delhi Gate, there is consternation among those who understand habitat traditions. Shekhar Gehlot, a village resident and an archaeology graduate, said many structures had already been lost to changes. The outer walls of the Daya Ram domed chattri were tiled five years ago, shuddered Gehlot. “The family fortunately did not make changes to the inner wall, which has beautiful paintwork,” he said.

Chaudhary Dharam Pal Singh, 80, said the chattri belonged to his ancestors. “We preserved it,” he said, not realising that their attempts to maintain the old structure had only marred its architecture. The octogenarian added that the family also owned the Jeet Singh haveli, “which must be over 200 years old”. After shifting to a new house, the antiquated haveli with its imposing central courtyard and handsome sandstone brackets lies in a shambles.

Singh’s son, Ajeet, added, “While some zaildars still retain their havelis, most are vacant and dying by the day. If the government helps us protect them, we will definitely cooperate in the exercise,” he said.

Ajay Kumar, project director of Intach Delhi chapter, felt that with proper conservation, villages like Najafgarh could turn into tourist spots. “Delhi needs lungs for its citizens and heritage localities like Najafgarh should be developed along these lines,” he said.

Lake

Status in 2019

Shilpy Arora, April 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shilpy Arora, April 6, 2019: The Times of India

NGT seeks report on declaration of Najafgarh as wetland from Delhi and Haryana governments

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has sought an action-taken reports from Delhi and Haryana governments over the declaration of wetlands in Najafgarh.

The directions were given after the Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH) filed an execution application in the green tribunal, alleging the Haryana government has rolled out a proposal to build a bund (check dam) near Najafgarh lake to reclaim lands belonging to farmers, and is therefore backtracking from its stand to declare it a wetland.

“We filed an execution application as the state government has not done anything to notify the area around Najafgarh lake as a wetland. The proposed bund goes against the wetland notification. There is a need to understand that destruction of the wetland will have a major impact on Delhi-NCR’s groundwater level, apart from destroying the ecology,” said Manu Bhatnagar of INTACH.

In 2016, the state government had submitted a brief document (a copy is with TOI) in NGT and the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF&CC), stating that 120.80 hectare in Kherki Majra Dhankot near Najafgarh lake is a wetland and will be duly notified as such by the state government.

Environmentalists fear construction of a bund will contain the water and destroy the wetland, which serves as a habitat for several bird species and acts as a major groundwater recharge zone for Delhi and Gurgaon. “The Haryana government is in a very tricky situation now, having itself committed in court and submitted in writing that it will notify Najafgarh as a wetland. Any proposal to build a bund now will destroy the wetland. However, the government can’t backtrack from its stand any more, as it has submitted in writing that Najafgarh is a wetland,” said Pankaj Gupta of NGO Delhi Bird Foundation.

In January, TOI reported that to woo voters in eight villages, the state government had proposed that villagers should sell their land to the government so that it can build a bund to protect their agricultural fields from flooding.

Farmers in the neighbouring villages claim that over 5,500 acre in eight villages — Dharampur, Momdheri, Daultabad, Kherki Majra, Dhankot, Chandu, Budhera and Makrola — remain flooded for most of the year, preventing them from cultivating the land.

As per an estimate, the 7km-long Najafgarh Jheel, located at the Delhi-Haryana border, has a potential to provide about 100 million litres of potable water a day to south-west Delhi and Gurgaon. The Najafgarh lake and drain are also the only outlets for floodwaters from Gurgaon. The lake and marshes have also been an important habitat for many plant species and hosts over 280 bird species, including greater flamingos, sarus cranes and greater white pelicans.