Delhi: Najafgarh

Contents |

A constituency profile

As in 2020

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, In far west, a seat no one has bagged twice in a row, February 7, 2020: The Times of India

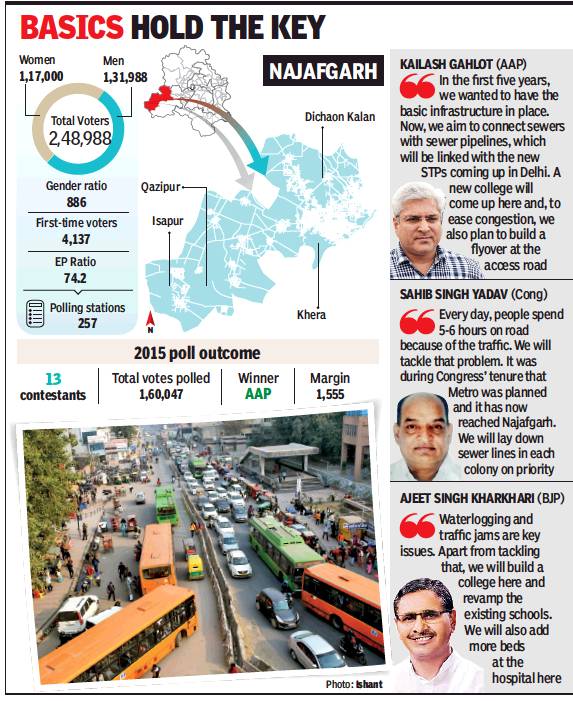

Waterlogged Streets, Traffic Snarls On Top Of Voters’ Minds

In Najafgarh, waterlogged streets and seemingly endless traffic snarls are key issues and, as such, the battle for this seat in the far west corner of the city will be fought around these. Sitting AAP MLA Kailash Gahlot, who holds the important portfolios of transport and environment in the incumbent government, was run close by Indian National Lok Dal’s Bharat Singh in 2015. This time around, though, the fight is likely to come from the two mainstream parties, BJP and Congress.

BJP’s Ajeet Singh Kharkari said Gahlot was now a VIP and not an “aam aadmi”.

The constituency, which has a mix of rural and urban population, has interestingly never re-elected a candidate.

The constituency, which has a large population base of Jats, stretches from Dichaon Kalan and Jharoda Kalan to Dhansa border with locations like Prem Nagar, Sainik Enclave, Samaspur Khalsa, Vinoba Enclave, Rajeev Vihar, Jai Vihar and Jaffarpur Kalan all included. Sunil Singh, a resident of Jaffarpur Kalan, said the area had seen tremendous improvement in the last five years, but traffic woes remained despite the huge relief coming in the form of Delhi Metro.

Crime

2016

The Hindu, January 25, 2016

Shiv Sunny

Gangsters are legends in this village

Elders of the notorious Mitraon village in Najafgarh rue the loss of a generation to violence.

If anyone ever suggests ‘Fauzi’ or ‘Balraj’ during the naming ceremony of a child in this village, they draw scornful and warning stares. But these are the very names many children demand to be rechristened with when they breach their teens.

Welcome to Mitraon village in Najafgarh area in South West Delhi whose younger generation idolises gangsters like Fauzi and Balraj — they are nothing less than “legends” for the teenagers here.

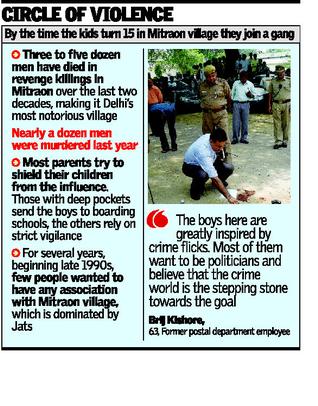

As per various estimates, three to five dozen men have died in revenge killings in Mitraon over the last two decades, making it arguably Delhi’s most notorious village. Since the start of last year, when four villagers were found charred in a car, around a dozen men have already been murdered.

It all began over a few acres of land in the 1990s. Today, this village has produced some of the most notorious gangsters like Manjeet Mahal, Naveen Khati and Ravinder Bholu.

“Today, the rivalries are no more just over property or money. It is now over a false sense of honour,” says Dependra Pathak, Joint Commissioner of Police (South-Western Range).

The younger lot in this village are inspired by Indian films that show orphans rising from railway tracks to rule over the underworld. They want to imitate gangsters who arrive at the village in suave SUVs with bodyguards flanking them.

Most parents do all they can to shield their children from the influence. Those with deep pockets send the boys away to boarding schools outside Delhi at the first opportunity.

The less fortunate ones rely on strict vigilance. They allow their children to interact with very few friends and track their movements closely.

“There are times when I have paid surprise visits to his school and even secretly followed him by another vehicle to know which places he visits and whom he interacts with,” says Sandeep Gehlot, father to a 16-year-old boy.

For several years Mr. Gehlot kept the TV remote with him. “I allowed my son to watch only children’s shows like Chhota Bheem and Motu-Patlu. He was never allowed to watch gangster films,” says Mr Gehlot, a farmer.

Sandeep is not alone when it comes to monitoring what children watch on TV. “The boys here are greatly inspired by crime flicks. Most of them want to be politicians at a later stage in life and believe that the crime world is the stepping stone towards the goal,” says Brij Kishore, a 63-year-old ex-employee with the postal department.

By the time the children turn 15, they are associated with one of the several small gangs from the village. Once the gang leader is arrested or killed, they see an opportunity to break away and form their own gang.

Even after severe crackdown on the gangs in the past, there are 15-20 small and big gangs operating from the village. A murder here is followed by another and the revenge cycle goes on.

All this takes its toll on the youth, particularly girls, when they reach marriageable age. For several years, beginning late 1990s, few people wanted to have any association with Mitraon village, which is dominated by Jats.

“Many members of our younger generation were unable to find brides or grooms because of fears of early widowhood or getting into legal troubles. The only thing residents of other villages discussed about Mitraon were the gang-wars. It became embarrassing for us to visit another village,” says Om Krishan, a local.

Despite no dip in the crime scene, the marriage situation has improved claim villagers. Yet, it took a retired government teacher of the village two years before he could find a groom for his daughter who was by then “way past her marriageable age”.

“My daughter is a government school teacher and under normal conditions she would have found enough suitors,” says the teacher, insisting that he faced this hurdle despite no one from his family being ever associated with any gang.

The older generation claims to have done their bit to end the rivalries between residents of the around 12,000-strong village. Village elders say they attend weddings at each others’ homes even as their sons and grandsons are warring against one another. But this has had little impact as the young criminal elements show scant regards for their elders. “Even at this age I am scared to smoke in front of my father. But the younger members do not care to even hide their guns when they come home,” says the school teacher.

Amid all this, police have been holding regular meetings with the village heads to keep the youngsters in check, but the ground reality is that they know that a round-the-clock deployment of a good number of police personnel in and around this village is the only way to prevent violence here.

Heritage, havelis

As in 2021

Mohammad Ibrar, February 13, 2021: The Times of India

From: Mohammad Ibrar, February 13, 2021: The Times of India

Just past Delhi Gate, you come to a haveli with a stone doorway adorned with intricate floral patterns. Inside, a teak doorway leads to a large courtyard where a nearly centuryold charpoy and an heirloom brass pot catch the attention. The traditional house could pass off for any well-preserved haveli of old Delhi. Gopi Singhal, the owner, is a cloth merchant and has spent many years conserving this ancestral haveli in Najafgarh in southwest Delhi.

Yes, Delhi Gate and havelis recall the lingering old-world charm of old Delhi. But Najafgarh, unknown to most people, is also a hub of havelis. Unfortunately, the town which bears the name of Mughal official Mirza Najaf Khan, is burdened now with burgeoning modernity and slowly losing its heritage character. Perhaps the most striking example of this time-eroded legacy is Delhi Gate. The words on the top of the structure now call it the Vad Kishan Lal Duar. The old gateway is so completely revamped that it looks like a contemporary construction. Sudheer, who runs a book store opposite the gate, recalled its renovation by a local politician two decades ago. “Some people call it Delhi Gate, but most of us know it by its new name,” he shrugged.

The gate, which has a plaque to commemorate the martyrs of World War I, is covered with tiles now. Suraj Kumar, senior conservator at Intach’s Delhi Chapter, rued that far removed from public consciousness, there was nobody to prevent the gateway’s shabby treatment. “Remnants of its old self are visible in the quartzite stone base and the Mughal-favoured Lakhori bricks interior, discernible at the spots where the tiles have fallen,” Kumar pointed out.

Past the gate and the statue of Jawaharlal Nehru lie several havelis. Many of these, such as the old haveli adjacent to an Arya Samaj Mandir, have just the Lakhori brick exterior surviving, the thin, flat red bricks proving their Mughal provenance. This is where Singhal’s haveli stands. “My home is 150 years old and is still stronger than most new houses,” said the 49-year-old cloth merchant, who claimed that his grandfather was often called up for jury duty in British courts prior to independence. Singhal remembers how people mocked him when he decided to conserve the old haveli. “They advised me to spend my money on a modern house instead,” he said. However, he realises that he might not have followed heritage norms during the renovation. “If we had got government support, we would have adopted scientific modes of conservation,” he admitted.

Najafgarh’s havelis now lie hidden behind shops and hoardings, some of them modified beyond recognition. Ashok Saini, owner of Sri Deshraj Jagdish Prasad Sweet Shop at the Old Anaj Mandi, claims that the road had havelis on either side. Few have survived. “The change began over 30 years ago,” said Saini, whose family has run the confectionary shop since 1880. “People left the rustic Najafgarh and settled in the city. No one bothered about their ancestral properties. In any case, people weren’t aware of the importance of preserving heritage houses. Neither did the government support them.”

Nearby, masons worked busily at a nameless haveli that Girish Jain, a Najafgarh businessman, bought in January. “I wanted to shift to a bigger place, so I bought this haveli. I have no idea how old the structure is,” said Jain. His wife, Sarika, informed that the haveli had three floors and a large terrace. “We are getting the place repaired. We are not touching the gate of the haveli because it is so very pretty,” she said. At Mitraon village too, a few kilometres from Delhi Gate, there is consternation among those who understand habitat traditions. Shekhar Gehlot, a village resident and an archaeology graduate, said many structures had already been lost to changes. The outer walls of the Daya Ram domed chattri were tiled five years ago, shuddered Gehlot. “The family fortunately did not make changes to the inner wall, which has beautiful paintwork,” he said.

Chaudhary Dharam Pal Singh, 80, said the chattri belonged to his ancestors. “We preserved it,” he said, not realising that their attempts to maintain the old structure had only marred its architecture. The octogenarian added that the family also owned the Jeet Singh haveli, “which must be over 200 years old”. After shifting to a new house, the antiquated haveli with its imposing central courtyard and handsome sandstone brackets lies in a shambles.

Singh’s son, Ajeet, added, “While some zaildars still retain their havelis, most are vacant and dying by the day. If the government helps us protect them, we will definitely cooperate in the exercise,” he said.

Ajay Kumar, project director of Intach Delhi chapter, felt that with proper conservation, villages like Najafgarh could turn into tourist spots. “Delhi needs lungs for its citizens and heritage localities like Najafgarh should be developed along these lines,” he said.

Lake

Status in 2019

Shilpy Arora, April 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Shilpy Arora, April 6, 2019: The Times of India

NGT seeks report on declaration of Najafgarh as wetland from Delhi and Haryana governments

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has sought an action-taken reports from Delhi and Haryana governments over the declaration of wetlands in Najafgarh.

The directions were given after the Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH) filed an execution application in the green tribunal, alleging the Haryana government has rolled out a proposal to build a bund (check dam) near Najafgarh lake to reclaim lands belonging to farmers, and is therefore backtracking from its stand to declare it a wetland.

“We filed an execution application as the state government has not done anything to notify the area around Najafgarh lake as a wetland. The proposed bund goes against the wetland notification. There is a need to understand that destruction of the wetland will have a major impact on Delhi-NCR’s groundwater level, apart from destroying the ecology,” said Manu Bhatnagar of INTACH.

In 2016, the state government had submitted a brief document (a copy is with TOI) in NGT and the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEF&CC), stating that 120.80 hectare in Kherki Majra Dhankot near Najafgarh lake is a wetland and will be duly notified as such by the state government.

Environmentalists fear construction of a bund will contain the water and destroy the wetland, which serves as a habitat for several bird species and acts as a major groundwater recharge zone for Delhi and Gurgaon. “The Haryana government is in a very tricky situation now, having itself committed in court and submitted in writing that it will notify Najafgarh as a wetland. Any proposal to build a bund now will destroy the wetland. However, the government can’t backtrack from its stand any more, as it has submitted in writing that Najafgarh is a wetland,” said Pankaj Gupta of NGO Delhi Bird Foundation.

In January, TOI reported that to woo voters in eight villages, the state government had proposed that villagers should sell their land to the government so that it can build a bund to protect their agricultural fields from flooding.

Farmers in the neighbouring villages claim that over 5,500 acre in eight villages — Dharampur, Momdheri, Daultabad, Kherki Majra, Dhankot, Chandu, Budhera and Makrola — remain flooded for most of the year, preventing them from cultivating the land.

As per an estimate, the 7km-long Najafgarh Jheel, located at the Delhi-Haryana border, has a potential to provide about 100 million litres of potable water a day to south-west Delhi and Gurgaon. The Najafgarh lake and drain are also the only outlets for floodwaters from Gurgaon. The lake and marshes have also been an important habitat for many plant species and hosts over 280 bird species, including greater flamingos, sarus cranes and greater white pelicans.

As in 2020

Shilpy Arora, Land or wetland? Haryana at a crossroads, February 16, 2020: The Times of India

From: Shilpy Arora, Land or wetland? Haryana at a crossroads, February 16, 2020: The Times of India

A large portion of the Najafgarh wetland, which squats across the Delhi-Gurugram border, could dry up if a check dam is built there as the Haryana government finds itself at the intersection of local land owners’ demands and concerns about a major environmental loss.

Gokul (name changed) is 67 and has spent all his life in Dhankot village, large parts of which remain submerged in water from the drain most months. Standing on the muddy bank, he looks across the vast expanse of still, dark water where, till a few days back, ‘Baguley’ or water birds were dancing around the cackling migratory birds, disturbing the perfect reflection of the blue sky and its milky clouds. “Years back, the waterbody used to make the soil so fertile that villagers grew watermelons here. Now, toxic sewage that flows into this nullah (drain) has polluted our agricultural land and we cannot cultivate anything. I would like a bund to come up in the area so that the land dries up,” he said, looking away.

Gokul echoes hundreds of farmers from eight villages spread over 5,600 acres of Gurugram district — Dharampur, Mohammad Heri, Daulatabad, Kherki Majra, Chandu, Budhera, Makrola, and his home, Dhankot — which remain flooded most of the year, rendering a good percentage of their land uncultivable. From right before the state elections last October, their demand to build a check dam on the drain found a prominent place in poll promises.

Last month, the newly elected government instructed its departments to carry out a feasibility survey for the construction of an embankment that will restrict water from flowing out of the Najafgarh drain, eventually drying up and destroying the eponymous wetland (or lake, as some call it) that squats across the Delhi-Gurugram border. The wetland hosts over 280 bird species, apart from being vital to the aquifer network of the National Capital Region (surveys have pointed out that the waterbody has the potential to provide about 100 million litres of potable water a day to southwest Delhi and Gurugram).

Move that dashed revival hopes

Environmentalists see this move as the government going back on its words because after years of denying its existence, in 2016, the Haryana government submitted a brief to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) expressing its intention to notify 1,200 acres in Najafgarh as officially ‘wetland’, a label that would protect the eco-sensitive marshes from construction activities. This was a giant leap from its earlier claim that only a ‘low-lying area’ exists in Najafgarh.

Manu Bhatnagar from Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH), who had filed a petition with NGT last year against the proposed embankment, said, “The government is absolutely backtracking on its stand. That is why we filed an execution application in April 2019 as the state government has not done anything yet to notify Najafgarh lake as a wetland. The proposed bund is contrary to notification of the wetland. There is a need to understand that the destruction of the wetland will have a major impact on the groundwater level in Delhi-NCR, apart from destroying the entire ecology.”

Although the land owners have a strong argument, several factors have led environmental experts to doubt their intentions. Firstly, the land these villagers own was originally part of the common pool, pieces of which they received through the process of consolidation. In the 1970s, Haryana government gave every villager private ownership of a piece of land from the common pool, all of which was previously owned by the Panchayat.

Secondly, as green activist Vaishali Rana Chandra has pointed out, the area only allows for seasonal agricultural activity. Despite that, the demand for a bund has raised concern that the ultimate objective is not to farm but sell. “As always, politicians are enticing the farmers since the land costs have shot up in the area,” she said.

A picture of confusion

The concerns, said Bhatnagar, are not unfounded as the Gurugram Masterplan 2031 contains proposals of developing several residential sectors in the Najafgarh basin that has recorded high flood levels many times in the last 100 years. The landowners, however, have consistently denied the very existence of any waterbody in the area. “There was no lake here some decades back. For the last 15-20 years, sewage has flowed into the Najafgarh area and it is impossible to carry out any kind of agriculture. Our lands have become wastelands. If the government notifies it as a wetland, the authorities should compensate us,” said a land owner Ramesh Vashisht of Sector 15 who has land in Budhera village.

Newly elected MLA from Badshapur Rakesh Daultabad, an Independent who has extended support to the BJP-JJP coalition government in the state, has approached the state human rights commission on behalf of the farmers. “About 35 years ago, a canal was made here. However, as the city expanded, waste started being dumped in the area. Due to continuous overflow of the drain, our agricultural fields are always submerged in filthy sewage,” he said.

However, every government record and map, including that of the Delhi Development Authority, state gazetteers, flood-control department of Delhi, NCR regional plans, the Union environment ministry (MoEFCC) and Isro wetland documents, mentions that the wetland dates back to 1807, and in 1865, the government dug a 51-km channel from the eastern end of the lake to the Yamuna, which came to be known as the Najafgarh drain. “After the floods of 1964, the Najafgarh drain was widened to accommodate the flood discharge. Delhi built an embankment on its side of the lake to prevent flooding of its areas,” said Bhatnagar.

Also, an INTACH study shows the Najafgarh basin is part of the centuries-old Sahibi Nadi, a dying ephemeral river that would flow through Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi before draining into the Yamuna.

Saving wetland saves lives

Historically, the Najafgarh basin, which is the winter home to about 2,000 flamingos and some endangered birds like the pink-headed ducks and the Siberian crane, has played a crucial role in helping drain flash floods. An estimated 7,000 cusec water flows from the city into Najafgarh drain during monsoon.

Due to this huge volume of runoff, the Najafgarh basin is extremely significant for groundwater recharge of the region. Of the several figures that show the extent of water scarcity in Gurugram, perhaps the most striking is its groundwater development stress index (groundwater abstraction as a percentage of groundwater recharge annually) which is at 209%. Hence, the district has been categorised as ‘over-exploited’ or ‘dark’ by the Central Ground Water Board. There is also a steady decline in the city’s water table at an average rate of 1.5 to 2 metre every year. Even though the authorities provide canal water through Yamuna, more than 50% of the city’s rising water demand is met from groundwater sources.

Instead of killing the wetland by building embankments and dams, green activists have proposed a slew of measures, including treating wastewater before releasing it into the lake, to revive and protect it. Bhatnagar said the wetland should be declared an area of permanent waterspread and farmers can be compensated to save the lake for groundwater recharge.

“The farmers may be compensated for use of land for water submergence as proposed by Haryana government in ‘Functional Plan For Water Recharge in the NCR’ and the money can be recovered from several revenue stream, including groundwater supply. Also, scattered gram sabha land in Delhi side can be consolidated along the embankment, and exchanged with private lands in the depression area,” he said.

Status as in 2021

Priyangi Agarwal, Oct 11, 2021: The Times of India

A report submitted by Wetland Authority of Delhi (WAD) to National Green Tribunal (NGT) says the water quality of Najafgarh lake does not meet the prescribed parameters with respect to pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) that will support propagation of wildlife and fish.

As the lake falls in both Delhi and Haryana, NGT has directed both governments to ascertain the water quality status.

The WAD report said the analysis of water quality done by Delhi Pollution Control Committee found pH at 5.06 and DO at 3.5 mg/l. The standard DO for a wetland is 4mg/l or more, while pH should be 6.5-8.5. However, the water quality met the desired criteria upstream where pH and DO were 7.44 and 7.5mg/l, respectively.

The lake receives a continuous input of sewage from Gurgaon and surrounding villages of Delhi. WAD told NGT that it was awaiting a green signal from MoEF for executing its environment management plan (EMP) for preventing entry of untreated sewage, removal of encroachment and conservation of the waterbody.

“According to Wetland Conservation and Management Rules, 2017, in case of trans-boundary wetlands, the central government shall coordinate with the state governments and Union Territory administrations. Delhi government asked MoEF in August this year to clarify if it could go ahead with the execution of EMP or wait for Haryana’s plan,” said the report. Though Delhi had submitted its EMP in December 2020, Haryana submitted its plan in September this year. The tribunal was also informed that an expert committee was examining Delhi’s EMP to identify actions that could be carried out independently.

In EMPs of both Delhi and Haryana governments, most recommendations for immediate, medium (within 2-3 years) and long term (3-5 years) were almost the same.

The common suggestions for immediate plans were notifications under wetland rules, boundary demarcation using geotagged pillars, constitution of Najafgarh Wetland Committee, constituting wetland mitras, commissioning hydrological assessment and species inventory and developing a comprehensive stakeholderendorsed management plan.

The medium-term plans included providing alternate road connectivity to settlements at two ends of Najafgarh lake, thus reducing vehicular traffic, especially during peak migration season of birds, conducting carbon and greenhouses flux assessments to determine the role of Najafgarh lake in climate change, installing signage at entry and exit and at key vantage points to communicate the value of the lake and dos and don’ts for people while being in the wetland. The common long-term measures included implementing ecological restoration measures.

Rawta

2023

Kushagra Dixit, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Kushagra Dixit, August 6, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi : While thousands of city residents suffered due to the floods this year, a few villages in Delhi and adjoining Haryana regularly get deluged with sewage and water from the Sahibi river or Najafgarh drain. With their fields submerged in water and paths connecting their fields destroyed, several people are even renting out their inundated holdings to migrant residents for fish breeding. The villagers believe that heavy silting of the Najafgarh drain and sewage released from Haryana are the cause of their woes.

Villages in South-West district, including Rawta which was recently adopted by the lieutenant governor and has a small population of 5,000, have remained inundated for years cutting off the residents from their main source of earning — agriculture.

Rajesh Kumar, a farmer in Rawta with five acres, said he managed to plant rice in a tenth of his landholding, but even that small bit was submerged a few weeks ago when the water level in Najafgarh drain soared.

Pointing at his field, he said, “Water has affected the agricultural roots of this centuries-old village. My field emerges from the water only for a few weeks in a year, but I still plough it to ensure it remains fertile after all the sediment deposited on it. I have been doing this for more than a decade now.” Kumar said there were more unfortunate farmers whose lands were now permanently under not only water but also stinking sewage.

The farmer alleged that both the central and state governments had “failed the villages” and that the MLA and MP they had approached had appeared “uninterested” in their problem. The villagers were not happy with the way the authorities have dealt with the Sahibi river, or Drain No. 8, as they call it, which runs parallel to the village’s 1,000 acres of agricultural land. “The things were not like this always,” claimed farmer Dharmendra Singh. “A part of the embankment of Sahibi river broke down and the water turned our farms into a pond. Besides, the drain carrying wastewater from Haryana also flows into the same pond, worsening the already bad situation.”

Ramesh Phalaswal said that LG VK Saxena has inspired some hope by adopting the village. “If the Sahibi river is dredged properly, the flooding could be prevented,” said Pha laswal. “There is some work under way to clean the channel now, but it will take at least three years to complete.” Meanwhile, migrants who rent the submerged fields for fish farming too claimed to be facing losses now. “I breed fish in a five-acre patch for which I paid Rs 1.5 annually till last year. This year the rent has slid to Rs 50,000 because the water level has risen and the fish are swimming beyond the rented area,” said Ram Babu Saini, who came to Delhi from Motihari in Bihar.

According to Paras Tyagi, co-founder of NGO CYCLE which works on village issu es, said that till date the farmers haven’t been officially compensated for the colossal loss to their farmland for more than 15 years now. “It is a matter of concern that while the moment the Yamuna overflowed into the city it became big news, the submerged farmlands of Rawta village are ignored by everyone,” said Tyagi. “Even the LG, who adopted the village, has no time for local communities. We wrote to him and to the wetland authority but our research and analysis were ignored and we were told that money was needed instead to rejuvenate the waterbodies. The experts consulted by Delhi government to protect the Najafgarh lake too gave no attention to the village and the affected farmers.”

When asked about this, irrigation department officials briefly said that they were working on desilting the Najafgarh drain and Sahibi river and assured that this would resolve the farmers’ problems.