Delhi: Nizam-ud-din basti and shrine

(→Rahim’s (Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s) tomb) |

(→Jamaat Khana Masjid) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 78: | Line 59: | ||

In 2011, Ahmed Nizami agreed to demolish the facade of his residence and shift it five feet inwards, providing the space to needed to restore the arcade. “The baoli and the water in it is very sacred to us and it is our duty to do whatever we can to protect it. Our house was originally located on the boundary wall of the baoli, a construction that took place in the 1950s when the baoli wasn't protected. AKTC was already doing work here, and we agreed to changes in the location of our house as it would protect the baoli. For the last few years, my family has been living elsewhere as construction work is still ongoing. It is inconvenient, but it's worth it to help the baoli,“Nizami said. | In 2011, Ahmed Nizami agreed to demolish the facade of his residence and shift it five feet inwards, providing the space to needed to restore the arcade. “The baoli and the water in it is very sacred to us and it is our duty to do whatever we can to protect it. Our house was originally located on the boundary wall of the baoli, a construction that took place in the 1950s when the baoli wasn't protected. AKTC was already doing work here, and we agreed to changes in the location of our house as it would protect the baoli. For the last few years, my family has been living elsewhere as construction work is still ongoing. It is inconvenient, but it's worth it to help the baoli,“Nizami said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Atgah12.jpg|Atgah Khan's Tomb-. Photo courtesy: Aga Khan Trust. This is a monument in the Nizamuddin area of south-east Delhi. |frame|500px]] | ||

“Over the last two years, in a very complex process, the AKTC team has demolished the 1950s structure to rebuild it with a setback and reconstructed the arcade on its 14th-century foundations. Nizami has also contributed to the costs of the reconstruction of his house now built in keeping with the historic character of the Nizamuddin area,“ said Neetipal, AKTC project architect. | “Over the last two years, in a very complex process, the AKTC team has demolished the 1950s structure to rebuild it with a setback and reconstructed the arcade on its 14th-century foundations. Nizami has also contributed to the costs of the reconstruction of his house now built in keeping with the historic character of the Nizamuddin area,“ said Neetipal, AKTC project architect. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 66: | ||

Conservation work is also being simultaneously undertaken on ChinikaBurj and Goga Bai Tomb, both 16th-century buildings located around the baoli that were in a severely dilapidated condition. One structure, Lal Chaubura at the southwest corner of the baoli, remains encroached and in danger of collapse. | Conservation work is also being simultaneously undertaken on ChinikaBurj and Goga Bai Tomb, both 16th-century buildings located around the baoli that were in a severely dilapidated condition. One structure, Lal Chaubura at the southwest corner of the baoli, remains encroached and in danger of collapse. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:History|NDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | |

| − | [[ | + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] |

| + | [[Category:India|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

=Delhi: Nizam-ud-din, village and shrine in 1902= | =Delhi: Nizam-ud-din, village and shrine in 1902= | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Extracted from: | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Delhi: Past And Present ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bengal Civil Service, Retired; | ||

| + | |||

| + | Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government, | ||

| + | |||

| + | And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division | ||

| + | |||

| + | John Murray, London. I9o2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' NOTE: ''' While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Crossing the canal near the ''' Sabz Posh tomb, ''' the village and shrine of Nizam-ud-din are | Crossing the canal near the ''' Sabz Posh tomb, ''' the village and shrine of Nizam-ud-din are | ||

| Line 451: | Line 461: | ||

Swapna Liddle, convenor of Intach Delhi Chapter, expressed outrage at the thought of people taking financial advantage of the dargah’s Sufi music sessions. She said that Intach accepted payments for taking people on curated walks through the historical quarter, but did not charge them for entry into the mausoleum or for attending the sama. | Swapna Liddle, convenor of Intach Delhi Chapter, expressed outrage at the thought of people taking financial advantage of the dargah’s Sufi music sessions. She said that Intach accepted payments for taking people on curated walks through the historical quarter, but did not charge them for entry into the mausoleum or for attending the sama. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Civic issues= | ||

| + | ==2019- March 20== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/nizamuddin-an-area-in-legal-strife-for-long/articleshow/74939017.cms Abhinav Garg, Nizamuddin: An area in legal strife for long, April 2, 2020: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | NEW DELHI: From being unable to clear parking mess, shut illegal guesthouses, or stop unauthorised construction near protected monuments, the Nizamuddin area has long been in the focus of courts hearing public interest matters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the past few years, the Supreme Court and Delhi high court have castigated Delhi Police and the South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) for major violations in the zone that has world famous monuments like Humayun’s Tomb and the Nizamuddin dargah and tourist attractions such as Sunder Nursery. | ||

| + | While most people are shocked that a Covid-19 hotspot emerged in the capital, local activists, lawyers and those familiar with the area see it as something that fits a pattern of violations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A stone’s throw from the local police station, the roundabout is situated on one of the most crucial arterial road linking central Delhi to east and south districts and sees traffic flow from all directions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2018, the Supreme Court had to point out how encroachers had a field day right under police’s nose as illegally parked autos, bikes and cars blocked even the Nizamuddin police station’s entrance. “At least clear your own backyard,” the SC judges told the police commissioner giving this example while underlining that just outside the building, junked vehicles had become breeding grounds for mosquitos, and were fuelling congestion on Mathura Road and beyond. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Last year, the area was again in focus when SDCM tried to pull wool over the eyes of the Chief Justice of Delhi high court in a PIL filed by the Jamia Arabia Nizamia Welfare Educational Society. Claiming it had taken strict action in removing encroachments and easing traffic congestion, the corporation had shown an empty plastic bottle, ice box, soft drinks trolley, plastic stool and a broken chair as “evidence” of how seriously it took the court’s orders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A furious then Chief Justice Rajendra Menon directed the SDMC commissioner and the DCP traffic to appear with an explanation. Soon a proper drive was carried out to end traffic congestion on Mathura Road, near Humayun’s Tomb, Neela Gumbad and Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah. They demolished 42 temporary sheds, sealed two illegal kiosks and removed a number of vending carts, iron benches, tables, iron grilles and boards, refrigerators and other articles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Last year, the local police informed the court that the lieutenant governor had formed a special task force on decongestion and parking in the area. It also claimed to have cracked down on unauthorised guesthouses near the dargah and booked hundreds of vehicle owners for illegal parking. Police had even conceded that they had found 69 illegal guesthouses in the area. | ||

| + | |||

=Do Siriya Gumbad= | =Do Siriya Gumbad= | ||

| Line 491: | Line 521: | ||

In December 2015, Delhi Development Authority (DDA) cleared 200 square yards on the approach to Do SiriyaGumbad of encroachments. | In December 2015, Delhi Development Authority (DDA) cleared 200 square yards on the approach to Do SiriyaGumbad of encroachments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Khan-i-Jahan Tilangani mausoleum = | ||

| + | ==The 2019 restoration== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F06%2F03&entity=Ar00402&sk=2535C724&mode=text Richi Verma, June 3, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: A 14TH-CENTURY PRIME MINISTER RESTS HERE- The Tomb of Khan-i-Jahan Tilangani was crumbling due to encroachment and neglect. It is being substantially conserved by AKTC.jpg|A 14TH-CENTURY PRIME MINISTER RESTS HERE- The Tomb of Khan-i-Jahan Tilangani was crumbling due to encroachment and neglect. It is being substantially conserved by AKTC <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2019%2F06%2F03&entity=Ar00402&sk=2535C724&mode=text Richi Verma, June 3, 2019: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Encroached Tughlaq-era tomb gets new lease of life | ||

| + | |||

| + | New Delhi: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The earliest octagonal tomb in India is a forgotten monument in the heart of Delhi. But 700 years after it was made, it is getting a new lease of life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 14th-century mausoleum of Khan-i-Jahan Tilangani is a little known building almost lost in the dense Nizamuddin Basti. Barely accessible and heavily encroached, the government forsake this monument for decades. It became so decrepit that loose stone blocks started falling off the dome and injuring the people illegally living inside it. They urged Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) to step in. And thus began the first-ever effort to conserve this monument. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Historians say this tomb is among the earliest structures in the Nizamuddin area and ideally should be protected by Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Instead, it is only under the umbrella protection of the local municipal body under a notified heritage list. “In terms of significance, Tilangani’s tomb is a unique monument and the earliest octagonal tomb in the country. All the other octagonal tombs like those in Lodhi Garden came much after it. It’s surprising that it was never notified as protected national heritage,” said an expert. | ||

| + | Tilangani was a Kakatiya prince from Telangana who became the prime minister of Sultan Feroz Shah Tughlaq. He built several mosques in the Delhi region and beyond. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And yet his tomb has shared the sorry fate of many other heritage buildings. Nearly two dozen families live inside the monument today. Access to it is almost impossible as lanes leading to the monument are barely one feet wide. “Until two years ago, tall trees could be seen growing atop the principal dome. When stone blocks started falling from the dome and injured some residents, some of the families residing within the structure requested AKTC to undertake urgent conservation,” said an official. | ||

| + | |||

| + | DDA’s Delhi Urban Heritage Foundation also promised to support the conservation effort. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once the conservation work started, unknown details of the 14th-century gem started to emerge. “On clearance of the roof, the AKTC team discovered that the dome was originally made of sandstone and much of the damaged stone elements were resting on the roof, amid other debris,” said an AKTC official. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He added, “The central chamber was provided to AKTC to conserve and over five feet of earth had to be removed to reveal the original flooring of this 700 year old structure. This was followed by over a year of painstakingly filling in the cracks, replacing missing masonry, underpinning the walls and finally restoring the lime plaster layer of the interior chamber. Conservation has been especially hard as the monument is hemmed in by modern structures, some built atop the structure.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Locals said that due to government apathy, several people started living inside the monument. Over the decades, they made indiscriminate additions to it. Once the interior is conserved, the team will work on the dome. The extent of the damage to it isn’t known yet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|NDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

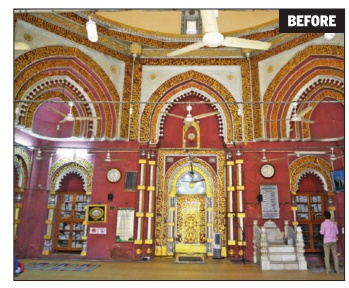

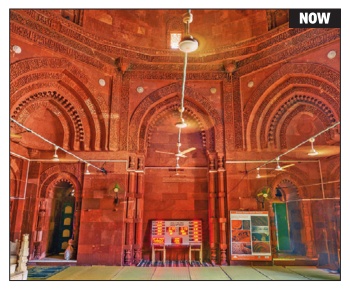

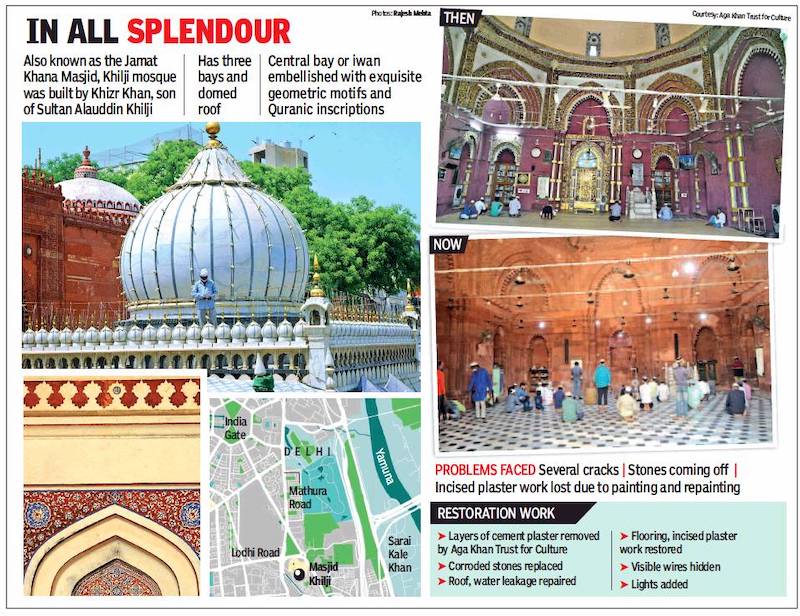

=Jamaat Khana Masjid= | =Jamaat Khana Masjid= | ||

| Line 516: | Line 580: | ||

According to the architects, portions of the wall were painted with leadbased paints that had set off the deterioration process in the sandstone blocks and in order to ensure long term preservation the paint layers were removed manually using soft sandpaper only . | According to the architects, portions of the wall were painted with leadbased paints that had set off the deterioration process in the sandstone blocks and in order to ensure long term preservation the paint layers were removed manually using soft sandpaper only . | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==As in 2021== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2021%2F04%2F13&entity=Ar00701&sk=7F41FE87&mode=text Mohammad Ibrar, April 13, 2021: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: The Jamat Khana Masjid, as in 2021.jpg|The Jamat Khana Masjid, as in 2021 <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2021%2F04%2F13&entity=Ar00701&sk=7F41FE87&mode=text Mohammad Ibrar, April 13, 2021: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Over 700 years old, the Jamat Khana Masjid in the Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah complex didn’t show its provenance, hidden as its history was under layers of enamel paints. Five years of effort put in by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) with the support of the local community, the mosque is almost back to its former glory. Calling it the first ever conservation of a living and unprotected mosque used by around two million people every year, AKTC removed years of paint, repaired leakages and revealed the intricate incised plasterwork of the 14th century building. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Najmi Nizami, whose family has been leading the prayers at the mosque for centuries, approached AKTC for its preservation around five years ago. “I used to visit Humayun’s Tomb with my wife and was impressed with the restoration work done there. The Nizamuddin Baoli was also conserved by AKTC in a scientific manner. Because of these examples, the Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah Committee thought Aga Khan Trust for Culture would be the best organisation to conserve this unprotected masjid, also called the Khilji Mosque,” revealed Nizami. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dargah committee is happy that the restoration is almost complete. Farid Ahmed Nizami, president of the committee, said work had progressed slowly because they had to make sure the mosque did not stop functioning. “Both AKTC workers and we had decided that devotees who visited the mosque or the people who came for the langar would be hampered by the restoration work,” said Farid Nizami. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Neetipal Brar, conservation architect at AKTC, added, “This work was an example of flexible conservation because the mosque was in use and we could not work during the month of Ramzan or during Eid and even on Thursdays and Fridays of the week.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | This was reiterated by AKTC CEO Ratish Nanda, who claimed the restoration was an example of joint work in which “the local community and the dargah committee assisted us”. Nanda explained that Jamaat Khana was among the earliest buildings in the Humayun's Tomb-Nizamuddin locality. Over four million pilgrims who come annually to the Nizamuddin Dargah also visit this mosque. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Brar, conservation architect at Aga Khan Trust for Culture, disclosed, “Over the years, the mosque had deteriorated, the stones were crumbling and the roofs were leaking. But instead of fixing this, the earlier protection workers used cement or painted over the corroded portions.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The restoration has seen the removal of lead paint that had begun affecting the red sandstone structure. The effort was also to reveal the original stone structure with its Quranic inscriptions and stone carvings. Of the three bays, the zenana (women’s section of the mosque) has seen the restoration of the ornamentation and the incised plaster work wherever there was evidence of its existence. Nanda also said that the domes or the gumbad had been repaired, while some stone parapets needed to be replaced. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Altamash Nizami, Dargah Committee member, assured that with the historic structure now restored, “we will make sure that there is no further damage to the structure and we maintain the integrity of the stone structure”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|NDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

=Kushaki Lal or Lal Mahal= | =Kushaki Lal or Lal Mahal= | ||

| Line 604: | Line 697: | ||

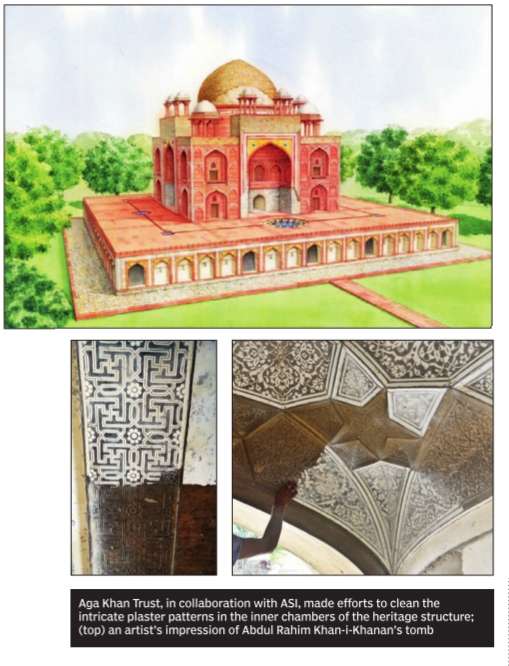

Historians say Abdul Rahim was a general and a poet during Akbar's time, who not just wrote dohas but also translated the Ramayana into Persian and was close to Tulsidas.These aspects of Rahim's life would be presented at a festival next year. | Historians say Abdul Rahim was a general and a poet during Akbar's time, who not just wrote dohas but also translated the Ramayana into Persian and was close to Tulsidas.These aspects of Rahim's life would be presented at a festival next year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2018: restoration of dome== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F07%2F03&entity=Ar00616&sk=FE53B230&mode=text Richi Verma, Mughal tomb gets dome marble back, July 3, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb.jpg|Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan’s tomb <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F07%2F03&entity=Ar00618&sk=8046B02D&mode=text July 3, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '' Khan-I-Khanan’s Tomb To Get ‘Original Finish’ '' | ||

| + | |||

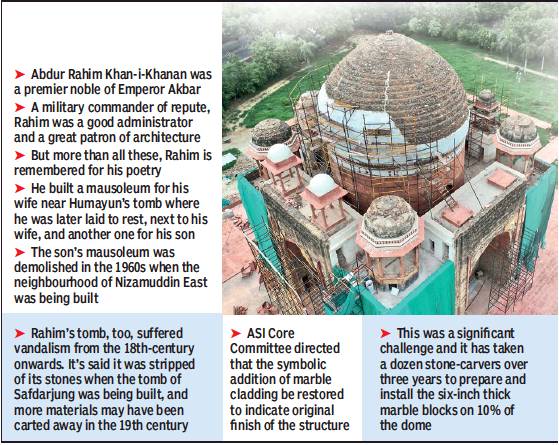

| + | The Khan-i-Khanan’s Tomb at Nizamuddin is the final resting place of Akbar’s premier noble, Abdur Rahim Khan. In its heyday, it was a magnificent building resembling the majesty and grace of the nearby Humayun’s Tomb. But while the tomb of Humayun has retained much of its original character, Rahim’s tomb has been a victim of vandalism for nearly three centuries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The tomb was stripped of its materials and all the marble cladding on the dome when the Safdarjung’s Tomb was built in the 18th century and even later. Now, Aga Khan Trust for Culture along with Archaeological Survey of India has been restoring the dome marble to indicate the original finish of the monument. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The tomb is located in the upscale Nizamuddin area. Experts said the gradual carting away of stones from the building compromised its structural stability. In 2014, AKTC with the support of InterGlobe Foundation began conserving the crumbling mausoleum. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Major structural repairs took over a year to complete. Under layers of soot and paint, intricate incised plaster decorations were discovered and have been carefully revealed by scraping off 20th-century paint layers. The ASI Core Committee directed a symbolic addition of marble cladding. “This was a significant challenge and it has taken a dozen stone-carvers over three years to prepare and install the six-inch thick marble blocks on 10% of the dome. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The stone carvers have used hand tools and manually lifted the heavy stone blocks,” said N C Thapliyal, AKTC project engineer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ASI has allowed only 10% of the marble cladding as the heritage body is against restoration in principle. The marble cladding is limited to the southern side of the structure and is thus mostly visible only from the Barapullah flyover and barely visible from the ground level. “However, this is enough to ensure structural stability, and though there is a demand for cladding the entire dome, there are other conservation priorities at the tomb at this time. More marble cladding of the dome will have to be deferred for a few years,” said Rajpal Singh, AKTC chief engineer. Conservationists added that the cladding on the edges of the dome enhances the structural stability of the dome by putting a vertical thrust on the dome and not allowing it to crack at the edges or even collapsing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | AKTC has also invited over 60 independent experts to peerreview the conservation works. Many of the peer reviews emphasised the need to not limit the cladding to only a portion. “Replacement of the lowest bands of marble on the dome will likewise assist in the appreciation of the tomb’s importance, though I feel that it would be better to replace all the missing marble, or at least restore the outline in plaster in a way that the marble could be replaced in future. The dome’s rubble core was not designed to be seen and does not provide proper protection from the weather,” said Benjamin Tindall, trustee, National Trust for Scotland. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dr R C Agrawal, former joint director general, ASI, said, “It is essential that marble cladding be done again to at least 50% to retain the historic character of the monument.” | ||

| + | |||

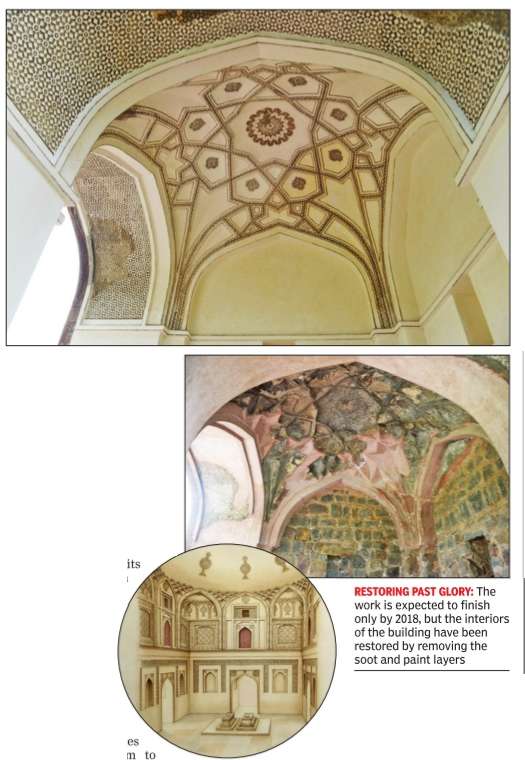

| + | ==The 2020 restoration== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2020%2F12%2F17&entity=Ar01004&sk=83722BB1&mode=text Manimugdha Sharma, December 17, 2020: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: The restored tomb of Rahim.jpg| The restored tomb of Rahim <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2020%2F12%2F17&entity=Ar01004&sk=83722BB1&mode=text Manimugdha Sharma, December 17, 2020: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

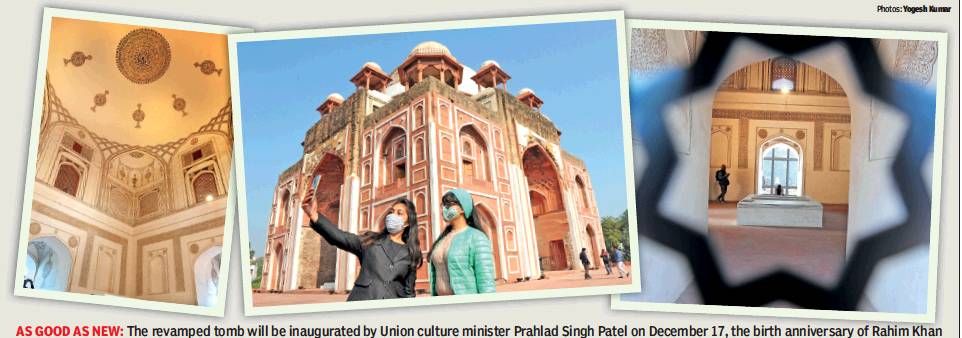

| + | Modernity has often been harsh on India’s architectural heritage. But there is one example in the heart of the capital where modern intervention has tried to reverse the damage wrought by centuries of neglect — Khan-i Khanan’s Tomb at Nizamuddin. The restoration that began in 2014 was completed on Wednesday. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The monument now has well-manicured chaharbagh gardens, re-laid stone pathways and illuminated arches. Inside the main mausoleum, the cenotaphs have been recast in white marble. The original graves in the tehkhana (vault) have also been restored. “The ceiling was scraped clean of the cement plaster and the original Mughal patterns restored,” revealed Ratish Nanda, CEO, Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which undertook the restoration in association with InterGlobe Foundation and Archaeological Survey of India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It took 1,75,000 craft days of work to restore this grandeur,” said Nanda. “We had to restore dignity to this monument for Rahim. He deserves his mausoleum to exist for posterity.” Mirza Abdur Rahim Khan was the stepson of Emperor Akbar and his premier noble bearing the title of Khan-i-Khanan (lord of the lords). The only son of Bairam Khan, Akbar’s ataliq or mentor, Rahim led Mughal armies to victory in Deccan, Gujarat and Sindh. But more than his military skills, he is known for the flourish of his pen. The brilliant poet and translator wrote with elan in Persian, Sanskrit and Hindavi, and his dohas are as popular as those of Kabir, Tulsidas and Surdas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rahim was appointed the ataliq of Prince Salim (future Jahangir) by Akbar. In 1598, during Akbar’s reign, Rahim began constructing a grand mausoleum for his wife, Mah Bano Begum. But when Jahangir ascended to the throne, Rahim saw ups and downs. Rahim’s two sons had hedged their bets on the losing Prince Khusrau in the succession struggle and so paid with their lives, with their father also suffering loss of prestige in court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rahim faced more humiliation after supporting the unsuccessful rebellion of Prince Khurram, the future Shah Jahan, against his father. His lofty title was taken away by Jahangir, though it was restored during his final days. “Eventually he died and there now remains neither respect nor humiliation,” commented Sir Syed Ahmad Khan on Rahim’s life in his 1840 work, Asar us-Sanadid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On his death in 1627, Rahim was entombed in the mausoleum built for his wife. As the Mughal Empire waned, its grand buildings were vandalised and cannibalised. Stones and other material from Rahim’s tomb too were extracted to build other buildings, most notably Safdarjung’s Tomb. When Sir Syed saw Rahim’s tomb, he wrote, “Today the mausoleum lies in ruin, with cows and buffaloes stationed on its premises. It resembles a skeleton of lime mortar and brick; cow dung is spread all over the place and the odour makes it very difficult to venture inside.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The marble cladding for the dome invited flak, but Nanda said without that “it was vulnerable to the elements.” Priyanka Singh, InterGlobe Foundation head, added, “There was some pushback, yes, but for a project of this scale, it was expected. We conducted 60 peer reviews of the conservation plan, getting endorsements from names like Ebba Koch and William Dalrymple.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The revamped tomb will be inaugurated by Union culture minister Prahlad Singh Patel on December 17, the birth anniversary of Rahim. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Details=== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/delhis-monument-of-love-has-been-restored/articleshow/79817477.cms Manimugdha S Sharma, December 20, 2020: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Modernity has often been harsh on India’s architectural heritage. But there is one example in the heart of the capital where modern intervention has tried to reverse the damage wrought by centuries of neglect — Khan-i Khanan’s Tomb at Nizamuddin. The restoration that began in 2014 was completed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The monument now has well-manicured chaharbagh gardens, re-laid stone pathways and illuminated arches. Inside the main mausoleum, the cenotaphs have been recast in white marble. The original graves in the tehkhana (vault) have also been restored. “The ceiling was scraped clean of the cement plaster and the original Mughal patterns restored,” revealed Ratish Nanda, CEO, Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which undertook the restoration in association with InterGlobe Foundation and Archaeological Survey of India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The monument has been revamped with well-manicured chaharbagh gardens, re-laid stone pathways and illuminated arches | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It took 1,75,000 craft days of work to restore this grandeur,” said Nanda. “We had to restore dignity to this monument for Rahim. He deserves his mausoleum to exist for posterity.” Mirza Abdur Rahim Khan was the stepson of Emperor Akbar and his premier noble bearing the title of Khan-i-Khanan (lord of the lords). The only son of Bairam Khan, Akbar’s ataliq or mentor, Rahim led Mughal armies to victory in Deccan, Gujarat and Sindh. But more than his military skills, he is known for the flourish of his pen. The brilliant poet and translator wrote with elan in Persian, Sanskrit and Hindavi, and his dohas are as popular as those of Kabir, Tulsidas and Surdas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rahim was appointed the ataliq of Prince Salim (future Jahangir) by Akbar. In 1598, during Akbar’s reign, Rahim began constructing a grand mausoleum for his wife, Mah Bano Begum. But when Jahangir ascended to the throne, Rahim saw ups and downs. Rahim’s two sons had hedged their bets on the losing Prince Khusrau in the succession struggle and so paid with their lives, with their father also suffering loss of prestige in court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1598, during Akbar’s reign, Rahim began constructing a grand mausoleum for his wife, Mah Bano Begum. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rahim faced more humiliation after supporting the unsuccessful rebellion of Prince Khurram, the future Shah Jahan, against his father. His lofty title was taken away by Jahangir, though it was restored during his final days. “Eventually he died and there now remains neither respect nor humiliation,” commented Sir Syed Ahmad Khan on Rahim’s life in his 1840 work, Asar us-Sanadid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On his death in 1627, Rahim was entombed in the mausoleum built for his wife. As the Mughal Empire waned, its grand buildings were vandalised and cannibalised. Stones and other material from Rahim’s tomb too were extracted to build other buildings, most notably Safdarjung’s Tomb. When Sir Syed saw Rahim’s tomb, he wrote, “Today the mausoleum lies in ruin, with cows and buffaloes stationed on its premises. It resembles a skeleton of lime mortar and brick; cow dung is spread all over the place and the odour makes it very difficult to venture inside.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ceiling of the tomb was scraped clean of the cement plaster and the original Mughal patterns restored. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The marble cladding for the dome invited flak, but Nanda said without that “it was vulnerable to the elements.” Priyanka Singh, InterGlobe Foundation head, added, “There was some pushback, yes, but for a project of this scale, it was expected. We conducted 60 peer reviews of the conservation plan, getting endorsements from names like Ebba Koch and William Dalrymple.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|NDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

=Telgangi tomb, renovation= | =Telgangi tomb, renovation= | ||

| Line 642: | Line 811: | ||

Cut to the present: there are dozens of families that have built rooms, toilets and kitchens abutting the monument. Walking around the historic structure is difficult. But a beginning has been made such that conservation architects are able to enter and access the Khan-e-Jehan Telangi’s tomb. And it is only a matter of time before Khan-e-Jehan Telangi’s tomb is put back on the tourist map of Delhi. | Cut to the present: there are dozens of families that have built rooms, toilets and kitchens abutting the monument. Walking around the historic structure is difficult. But a beginning has been made such that conservation architects are able to enter and access the Khan-e-Jehan Telangi’s tomb. And it is only a matter of time before Khan-e-Jehan Telangi’s tomb is put back on the tourist map of Delhi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Women’s entry= | ||

| + | ==2018: restricted in Hz. Nizamuddin’s burial chamber== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F12%2F08&entity=Ar00616&sk=6F4CCDE6&mode=text Mohammad Ibrar, Dargah falls back on tradition, but historians say practice un-Islamic, December 8, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Women’s entry to other major shrines in Delhi.jpg|Women’s entry to other major shrines in Delhi <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F12%2F08&entity=Ar00616&sk=6F4CCDE6&mode=text Mohammad Ibrar, Dargah falls back on tradition, but historians say practice un-Islamic, December 8, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''NO ENTRY OF WOMEN AT NIZAMUDDIN’S BURIAL CHAMBER'' | ||

| + | |||

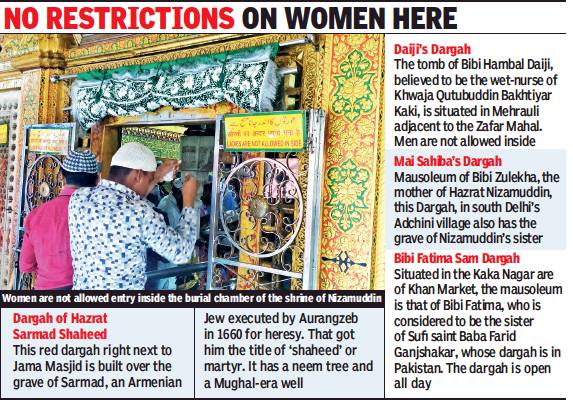

| + | The Nizamuddin dargah committee insists there is no discrimination against women. This after a Pune-based law student petitioned Delhi high court, citing the Supreme Court’s Sabarimala verdict, and demanded entry of women into the shrine of the Sufi saint. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fareed Nizami, member of the committee and a descendant of Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya, was asked why women aren’t allowed inside the burial chamber of the saint who lived between the 13th and 14th centuries. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “It’s all because of a 700-year-old custom, and because there is not enough space for people in the sanctum sanctorum,” Nizami said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He added, “Even women members of our family do not enter the grave.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The petition by lawyer Kamlesh Kumar Mishra states: “Nizamuddin Dargah by its very nature is a public place and prohibition of entry of anyone in a public place on the basis of gender is contrary to the framework of the Constitution of India.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hazrat Nizamuddin died in Delhi in 1325. But the current mausoleum was only built in 1562. Incidentally, the grave of Moinuddin Chishti, Nizamuddin’s predecessor and of the same Chishtiya order, is open to all. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Altamash Nizami, the ‘baradar’ and ‘peerzada’ of the dargah said, “There is no trust of the dargah. We are the Anjuman Peerzadgan Nizamiya Khusrawi coordination committee that manages the baradari system. We will respond when we get the notice from high court.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fareed Nizami also claimed, “We have a separate mosque for women and there is sitting arrangement at the dargah. There is only a stonelatticed wall or jaali that separates them from the grave, which they can see when they pray.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | And yet, a notice on a yellow board hung outside the burial chamber announced that women are barred entry. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Historian Sohail Hashmi said this restriction on the entry of women is at Nizamuddin only as there is no religious sanction for the norm. “There are many dargahs all over India where women are allowed. This shows that there is no Islamic rule barring entry of women, including the Ajmer dargah,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But Erum Khan, who runs an event management company and regularly visits the dargah, said, “If there is a custom at the dargah, we should respect it.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The petitioner, however, challenged it on the grounds that this discrimination is only at Nizamuddin shrine and not other dargahs. | ||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

| Line 647: | Line 848: | ||

[[Raheem (Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khana) ]] | [[Raheem (Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khana) ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History|NDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|DDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINEDELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE | ||

| + | DELHI: NIZAM-UD-DIN BASTI AND SHRINE]] | ||

Revision as of 15:52, 14 April 2021

The 1902 section was written around 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

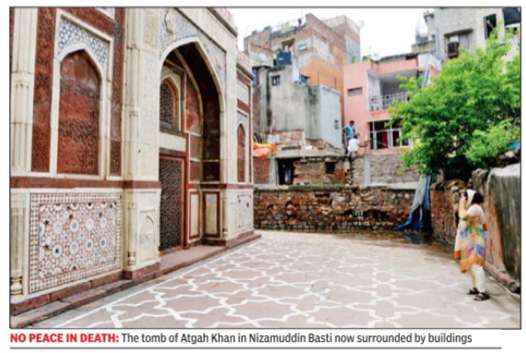

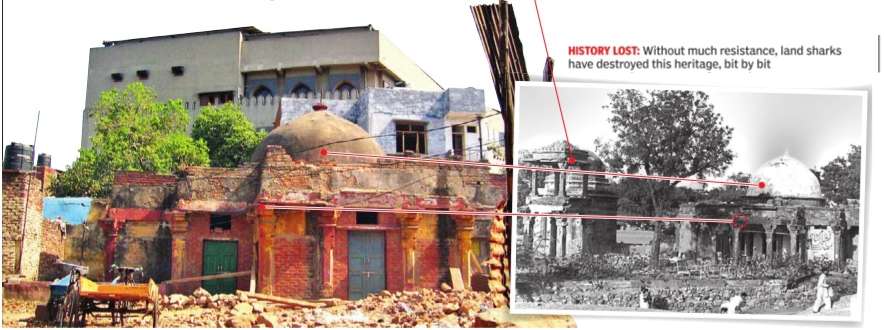

Atgah Khan's tomb

Illegal encroachment

Sources:

The Times of India, August 11, 2015

The Times of India, October 3, 2015

The tomb is situated on the northern edge of Nizamuddin, known for the dargah of the 13th century Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya.An inscription on the southern door of the tomb mentions that it was finished in the mid-16th century.

Historians said there were graves in the area around the tomb, where the unauthorized construction was taking place. “Atgah Khan's tomb has a crypt that is much larger than the domed tomb structure. The house is actually being built on the top of the crypt, said a source. The crypt of the tomb has been illegally occupied for many years and the ASI has not been able to get it vacated.

The ASI has not found it easy to keep tabs on illegal construction and encroachments around the tomb. The area of Nizamuddin is very densely populated with a number of encroachments near the monument over the past few years.

ASI says monument under threat as Delhi Police And South Corporation ignored its multiple complaints

In 2015, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) filed a police complaint against an unauthorized construction adjacent to the 16thcentury tomb of Mughal noble Atgah Khan in Nizamuddinbasti. With no action by the authorities, the construction has now materialized into a three-storey building. According to officials, the construction work was first spotted by locals. Locals from the area said that overnight a new building suddenly came up right on top of the wall surrounding the tomb. The illegal building now overshadows the tomb. Historians said that there were graves in the area around the tomb, where the unauthorized building was coming up. “The tomb has a crypt that is much larger than the domed tomb structure. The building is actually being built on the top of the crypt, said a source.

The area is very densely populated, and a number of encroachments have taken place near this monument over the last few years. The crypt of the tomb has been illegally occupied for many years, and Archaeological Survey of India has not been able to get it vacated.

Baoli (stepwell)

The Times of India, August 21, 2016

Richi Verma

The baoli at Nizamuddin is significant for more than one reason. The water of this 14th-century step-well, an ASI-protected monument, is considered sacred because it was built during the lifetime of HazratNizamuddinAuliya.But in the last few years, the monument has been hemmed in from all sides by modern constructions, altering its original design.

In 2016 Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) team completed the reconstruction of the western arcade of the baoli that had been demolished in the 1950s to build a residential structure. Experts said the baoli was the only one in Delhi with water to the brim, possibly due to its proximity to the riverbed and two tributaries of the Yamuna, now called nullahs.

Till the early 20th century, the baoli was lined with domed structures. These structures were in a dilapidated state and had to be conserved in partnership with the locals. The western arcade, in particular, required special attention.“The arcade, visible in archival images, together with the domed structures, was a significant archaeological feature and the stone pillars were still standing. We had to make an effort to reconstruct the arcade,“ said Ratish Nanda, CEO, AKTC.

Since the arcade could only be reconstructed by demolishing the residential structure that had replaced it, AKTC approached PirKhwaja Ahmed Nizami, the sajjadanashin and muttawali of the dargah. The pirzadas or keepers of the dargah have great reverence for the baoli, since it still, miraculously , holds fresh water.

In 2011, Ahmed Nizami agreed to demolish the facade of his residence and shift it five feet inwards, providing the space to needed to restore the arcade. “The baoli and the water in it is very sacred to us and it is our duty to do whatever we can to protect it. Our house was originally located on the boundary wall of the baoli, a construction that took place in the 1950s when the baoli wasn't protected. AKTC was already doing work here, and we agreed to changes in the location of our house as it would protect the baoli. For the last few years, my family has been living elsewhere as construction work is still ongoing. It is inconvenient, but it's worth it to help the baoli,“Nizami said.

“Over the last two years, in a very complex process, the AKTC team has demolished the 1950s structure to rebuild it with a setback and reconstructed the arcade on its 14th-century foundations. Nizami has also contributed to the costs of the reconstruction of his house now built in keeping with the historic character of the Nizamuddin area,“ said Neetipal, AKTC project architect.

Conservation work is also being simultaneously undertaken on ChinikaBurj and Goga Bai Tomb, both 16th-century buildings located around the baoli that were in a severely dilapidated condition. One structure, Lal Chaubura at the southwest corner of the baoli, remains encroached and in danger of collapse.

Delhi: Nizam-ud-din, village and shrine in 1902

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

Crossing the canal near the Sabz Posh tomb, the village and shrine of Nizam-ud-din are immediately reached on the left. North of the Dargah are a number of buildings of the severer middle Pathan type, including one on the left of the side road to it, known as the Barah Khambhe, or Twelve-Pillared (which seems to have been a tomb chamber with arcades round it, and may have been the original of the Chausath Khambhe, and another behind it of red sandstone, known as the Lal Mahal, or Red Palace.

This was once a very pretty pavilion of the earlier Pathan style (very possibly it was a building of Ala-ud-din for royal accommodation when the court visited the saint), and, with the interior of the mosque of the Dargah, links that style to the buildings of severer mould on this site. Among these again, at the south-east corner of the village, is a fine roofed mosque, known as the Sanjar mosque, which once had four courts, like that of Khirki each measuring forty-three by thirtythree feet.

These are larger than the Khirki quadrangles, but the arcades between the courts being much narrower than these, the total area covered by this mosque is considerably less than in the case of the more southern example. It was built by Khan Jahan in 1372 A.D., and is well deserving of a visit, though much of it is now filled up with mud houses. To the east of the mosque is a fine tomb, also of the middle Pathan period, known locally as that of the Talanga Nawab.

The first Khan Jahan was originally a Hindu follower of the Talingana, or Warangal chief, who was brought to Delhi after his capture, and this tomb is no doubt connected with the latter or some descendant of his.

The Dargah or shrine of Shekh Nizam-ud-din-Aulia

The Dargah or shrine of Shekh Nizam-ud-din-Aulia, whose full title was Shekh-ul-Islam Nieam-ul-hak-wa-ud-din, is with the other Chisti shrines at Ajmir, the Kutab, and Pakpattan, one of the principal places of Muhammadan reverence in all India.

This saint was the last of the four, and successor to Shekh Farid-ud-din of Pakpattan, known as Shakar Ganj. No story in the annals of ancient Delhi is more widely told than that of the quarrel of those, frequent mediæval opponents, the King and the Priest, for do not the desolation of Tughlakabad and the bitter water of the shrine tank bear witness to it to this day. In its full form the tale runs that the Emperor Tughlak Shah impressed the workmen of the saint to finish his new fortress and city.

The saint thereupon prosecuted his labours on the tank by means of oil light, whereupon a royal mandate forbade the sale of oil to him. The prayers of the saint then prevailed, so far that the workmen were miraculously supplied with light from the water of the tank, which enabled them still to work upon it at night.

In his wrath, the Emperor cursed the water of the tank, and it became bitter, and the saint in retaliation cursed the city of Tughlakabad What is more certain, is that Tughlak Shah did meet his death through the treachery of his son, assisted by the Shekh, who, while the king was approaching Delhi, and was known to be uttering threats against him, kept on saying tranquilly to his disciples: “Dilli hanoz dur ast” (“Delhi is still distant”), a saying which has passed into a proverb in India.

If, as tradition runs, the Shekh also had knowledge of the death of Jelal-ud-din-Khilji, which seemed at the time supernatural, it may be shrewdly suspected that he was also in league with a parricidal nephew on that occasion. He was, no doubt, one of the leading politicians of his day, and as such was probably as unscrupulous as his compeers and opponents, but there seems to be no ground whatever for attributing the origin of Thagism to him, and, as a matter of fact, this must have been Hindu.

The saint, who settled at Delhi in the time of the Emperor Balban died at the advanced age of ninety-two, in 1324. According to Abulfazl, he was known as Al Bahháth, the Controversialist, and Mahfil Shikan, the Confounder of Assemblies.

The entrance gate to the Dargah bears the date of 1378 A.D., and, like the inner gate beyond the tank, was built by the Emperor Firoz Shah Tughlak, who next to Ala-ud-din was the greatest of the early benefactors of the place. The plan of the interior given here, the first ever made, will render the following description of the interior intelligible. On either side within the entrance is an old Pathan tomb, and by that, on the right, is a mosque of two storeys, a rare arrangement; south of it again is the marble pavilion and grave of Bai Kokal De, a prima donna of the Emperor Shah Jehan, and behind that is an old cupola borne by red sandstone pillars.

The gravestone of this lady is a very beautiful one, and should be visited from the gallery at the south end of the tank, to which the paved way, picturesquely covered in at the end, leads along the east side. The tank, or Baoli, into which men and boys dive from the surrounding buildings, is named “Chashma dil kusha,” or the “Heart-alluring spring” (this gives the date of 713 H., or 1312 A.D., which does not correspond with the era of Tughlak Shah, who was murdered in 725 H., after a reign of four years); an archway now in the water on the east side of the tank is said to conduct to a cell once occupied by the saint.

The inner and third gate beyond that of Firoz Shah on the south side of the tank, which leads to the actual enclosure of the Dargah, is of much later date, but no longer bears any inscription. Beyond it is an extremely fine “imli,” or tamarind tree, affording a beautiful shade, and at the side of it is an octagonal marble receptacle, filled with sweets and milk on special occasions, like the great cooking pots at the Ajmir shrine.

In the angle behind this gate on the right is a Meeting Hall, or Majlis Khana, said to have been built by the Emperor Aurangzeb. In front of the gate and in the middle of the centre court is the Tomb of the saint, with the Jam’át Khana, or mosque, to the west of it. The structure over the tomb has been rebuilt and restored by many pious donors, and but little ancient work is left in it now. A wide verandah runs round the exterior, and light is admitted to the grave chamber by pierced marble screens in the inner walls of this. The ceiling of the verandah was restored at the expense of the late Mr R. Clarke, B.C.S. Round the grave, which is always covered, is a low railing of marble, and above it is a canopy of wood, inlaid with mother-o’-pearl.

Two inscriptions on the tomb describe it as the “Kiblahgah-i-khas-o-am,” and the Kubbai-Shekh, or the “Place of prayer to which all, great and small, turn,” and the “Dome of the Saint.”

Jam’at Khana Mosque/ Khizri Mosque

The Jam’at Khana Mosque, known also as the Khizri Mosque, is an extremely fine building of the ornate earlier Pathan style. It cannot have been the work of the Emperor Firoz Shah, who, however, restored it, and may have rebuilt the side rooms; and though called after Khizar Khan,1 the son of Ala-ud-din-Khilji, it seems probable that it was begun at least by the latter, as the centre bay more closely resembles the Alai Darwazah of that monarch than any other building in Old Delhi, and the son was murdered within a year of the death of his father. [1 Humayun is represented as seated on the ground to the right, clad in gold brocade over a crimson dress, and wearing a small reddish turband, such as Rajputs wear, with a black plume in it. His face is pleasing and intelligent, and he looks scarcely more than thirty years of age. Behind him stand three graceful and well-painted figures, reminding one of those recovered in the damaged frescoes at Fatehpur Sikri, one in blue with a chauri, one in white with, the king’s sword, and one in red with rose-water. Other graceful attendants stand by these, all wearing “kamar bands,” or waist-belts, and all well drawn and well painted, and showing unmistakable signs of Italian influence. Between the two kings is a green cloth with wine vessels and cups of silver, and fruit upon it.

On the left side is seated Shah Tahmasp, in a red dress over cloth of gold, girt by a black belt supporting the black scabbard of his sword; he wears a white gold-barred turband, wound round a high kulah, or pointed cap. Behind him are attendants with matchlocks and sword and hawks and golden dishes. In front of him are seated a body of Persian nobles in bright robes, each with his flagon, and in the right foreground of the picture are musicians with tambourine, flageolet, guitar, zither, and panpipes. Between these groups are two dancing girls performing elaborate body posturings, one clad in golden striped, and one in dull robes, and both with very long tresses behind, surmounted by large bosses of silver; the former is about to refresh herself with a cup of wine. Shah Tahmasp was the second of the Safavean kings of Persia, and reigned from 1526 to 1571.

It was to him that Queen Elizabeth commended Mr Anthony Jenkinson, addressing him as “The Right Mightie and Right Victorious Prince, the great Sophie, Emperor of the Persians, Medes, Parthians, Hiroeans, Carmanians, Margians, of the people on this side and beyond the river Tygris, and of all men and nations between the Caspian Sea and the Gulfe of Persia,” a commendation which availed the English merchant nothing, for he was ignominiously repulsed from the king’s presence.] The front arches, with their heavily engrailed curves, are particularly handsome and effective, and the carved work of the kiblah niche is unusually elaborate and beautiful. The fine timber doors and the Hindu heads of the doorways also deserve special notice. The golden cup hanging from the dome of the central chamber is said to be the one originally suspended there.

South of the tomb of the Shekh come the graves of many persons of note, and amongst them not a few of royal blood, resting as close as possible to his holy influence. Next to the mosque in the front row is a marble enclosure with the grave of Jahanara Begam, daughter of Shah Jehan and companion of his captivity, which she survived sixteen years, outliving her rival sister Roshanara Begam, by ten

The grave consists of a marble block hollowed out so as to form a receptacle for earth in which grass is planted: at the north side stands a handsome headstone, with verses supposed to have been written by the Princess: “Let green grass only conceal my grave: grass is the best covering of the grave of the meek.” On either side of her are buried the son and daughter of two of the late Moghal Kings—doubtless because the cost of a separate place of burial for them was not forthcoming.

In the next enclosure on the east lies Muhammad Shah (d. 1748), the unhappy Emperor who saw the capture of Delhi by Nadir Shah, and near the fallen head of her house lies the Moghal princess who was married to Nadir Shah’s son, and her baby.

The entrance to this enclosure and to that opposite on the further side of the passage is decorated with marble doors, on which extremely beautiful patterns of flowers and leaves have been carved. The conception of these hardly appertains to the region of high art, but the execution is well worthy of notice, as are the beautiful pierced marble screens in the walls of the enclosures.

The third contains the grave of Prince Jehangir, son of the King Akbar II.: it was under completion when Bishop Heber visited the Dargah. The people of Delhi say that the real cause of the prince’s removal to Allahabad was that he actually fired at the British Resident, Mr Seton, in the king’s palace, the ball passing through that gentlemen’s hat.

Yet another gateway leads from the central court to the well-shaded quadrangle on the south, which contains the Chabutra Yáráni and the tomb of the poet Khusrau, as well as many other graves, among them several of the actual disciples of the saint. The first was the platform where the friends of Nizam-ud-din-Aulia used to sit with him in his lifetime, and was thence called “the Seat of the Friends.”

The second covers the remains of the first and most renowned of the poets of the modern language of India, Amir Khusrau, popularly known as the Sugar-tongued Parrot (“Tuti-i-shakar-makál”), and also called in the inscription on his tomb Adim-ul-misal, or the Peerless, both designations giving the date of his death, 725 H., or 1324 A.D. He was a devoted friend of Shekh Nizam-ud-din, and died at an advanced age soon after his master, whom he refused to survive, Among the adventures of his life he was once captured by the Moghal invaders. The present tomb dates from the early years of the seventeenth century. The grave chamber is surrounded by two galleries, and the light which reaches it is very subdued.

[1This {which?} was the prince, whose loves with the Dewal Rani were celebrated in one of the most famous poems of Amir Khusrau.]

The well-known historian, Khondamir, was also buried near by, but the Dargah guardians are unable to point out his grave. Beyond the west wall of the southern court is an extremely pretty grave and mosque of one Dauran Khan; and outside the east wall of the central court — it can also be reached by steps from the gallery along the east side of the tank—is the tomb of Azam Khan, or Atgah Khan, commonly known as Taga Khan.

This man, whose actual name (this is really rather in the style of Humpty Dumpty in “Alice in Wonderland”) was Shamsud- din-Muhammad, saved the life of the Emperor Humayun on the occasion of his final and irretrievable defeat by Sher Shah, and won alike the further consideration of the Emperor Akbar, the title of Azam Khan, and the Governorship of the Punjab, by defeating Bairam Khan at Jalandhur when the latter went into half-hearted rebellion against his master.

His wife was a foster-mother to Akbar, as well as Maham Anagah and no doubt great ealousy arose between the families of the two ladies, which culminated in Adham Khan, son of the latter, murdering Azam Khan in the royal palace at Agra in 1556 A.D.

The murderer then proceeded to the door of the private apartments of the palace, and upon the Emperor issuing forth, tried to seize his hands in order to secure his pardon. Akbar, however, freed himself by violence, and laid Adham Khan senseless by a single blow, which the court chronicler assures us was like that of a mace, and his body was then, by the Emperor’s orders, twice thrown from the lofty palace terrace into the court below.

The corpses both of the murdered man and of his murderer were sent to Delhi, the former tu be buried here, and the latter at the Kutab, where his mother, who is said to have died of a broken heart, was soon laid beside him The tomb of Azam Khan must have been one of the most effective and pleasing specimens of polychromatic decoration in the whole of India, and even in its present halfruined condition will be considered by most people extremely pretty.

The red sandstone used in it is of an unusually fine colour, and the marble has assumed an ivory hue. Three graves stand on the marble pavement of the sepulchral chamber, decorated with white and black stars. The enclosure wall on the west side was once brightly decorated with encaustic tiles, of which some traces still remain. Two hundred feet to the south-east of this tomb, and practically opposite the Chabutra Yáráni courtyard, is the last building of special interest at the Dargah — the Chausath Khambhe, or Sixty-four Pillared Hall.

This is the family grave enclosure of the sons of Azam Khan and of his brothers, several of whom, like Adham Khan, were commanders of 5000, which was practically the highest military rank that could be attained in ordinary circumstances under the Moghal Emperors.

The building was raised by Mirza Aziz Kokaltash, foster brother of the Emperor Akbar, who died in 1624 A.D., and round him are buried a number of members of the family which was known as the Atgah Khail, or Gang, so widely did it spread and flourish under imperial favour. The grey marble arches of the hall are pleasing, and the effect of the interior is decidedly good, and reminds one in a way of the beautiful grey marble chamber of the Moti Masjid of Agra.

To the east of Nizam-ud-din on the road to Mubarikpur are the remains of a fine bridge of later Pathan style, spanning the same ravine as is bridged near the tomb of Sikandar Shah Lodi, north of the village of Khairpur, and which joins that from Khirki and Chiragh Delhi near this point, and passes under the Barah Palah to the Jumna.

Delhi: the Khairpur buildings

[This the general area that begins with the monuments across the road from the Purana Quila (Old Fort)/National Zoo and continues towards the Lodi Gardens]

Proceeding west from Nizam-ud-din towards the tomb of Safdar Jang, the road passes the first-named village one mile and a half away on the left, and the last-named half-a-mile away on the right. Most persons will perhaps hardly care to walk or ride to Mubarikpur, but every one who can spare an hour should certainly visit the Khairpur buildings.

These are four in number. That nearest the road, and between it and the village, is the tomb of Muhammad Shah, third of the Syad kings (died 1445 A.D.), which is figured in Mr Fergusson’s “Eastern Architecture.” The building is octagonal, and has an exterior arcade, with sloping angles, similar to those of the tombs of Isa. Khan and Mubarik Shah; the decoration of the interior of the dome must once have been unusually beautiful.

In the village itself, 200 yards further north, is a striking mosque, approached through a very fine gateway, which, from a distance, looks like a tomb. The interior of the gateway, reached by a high flight of steps, is singularly well proportioned and lofty, and was evidently modelled upon the Alai Darwazah Beyond the gateway is an extremely picturesque courtyard, with a mosque on one side and an Assembly Hall on the other, bearing the date of 1498 A.D.

This mosque was once entirely covered by the most beautiful plaster decoration, and still retains much of this. The plaster was relieved by colour in the form of patterns of encaustic tiles, and is quite the most beautiful specimen of this class of ornamentation that exists in India. On the north outskirt of the village is a second tomb without name, on which some tile-work of very bright blue may still be seen; and 400 yards beyond it again is the tomb of Sikandar Shah Lodi, who died in 1517—only nine years before the Moghal conquest of India.

This tomb is strikingly situated in a walled enclosure which, like Chiragh Delhi stands on the banks of a deep depression, spanned by a bridge of seven arches, carrying the high road that then connected Firozabad and the north with Siri and Old Delhi.

The tomb itself is a fine building, but the situation of it is the most pleasing thing connected with it. The pillar which bears the lamp at the head of the grave was once a column of a Jain temple; and it is curious how Hindu details were beginning to reassert themselves in Muhammadan buildings just before the time of the fresh Muhammadan conquest by the Moghals.

The tomb and mosque of Mubarik Shah lie rather more than a mile south of the high road in the village of Mubarikpur. This king was the second of the little-known Syad dynasty, and was murdered in 1433 A.D. The tomb is octagonal in form, and is surrounded by an arched colonnade; it is the earliest of those built in the later Pathan style and, in consequence encaustic tile-work is employed on it but sparingly, the freer use of this being a subsequent development. The angles of the tomb have sloping buttress piers, and above the dome, surrounded by octagonal cupolas, is a lantern of red sandstone.

Rising above a battlemented wall in the midst of trees, it is very picturesque. Outside the enclosure of the tomb is a mosque with two rows of bays and three large domes. Beyond the village to the east is a group of large tombs of the same age, known as the Tin Burj; the principal of these is, according to tradition, the tomb of Khizr Khan, the first Syad king, but this is hardly probable. A mile south of Mubarikpur is the Moth-ki Masjid, a fine mosque built in 1488 A.D., by Sikandar Khan Lodi, which served as a model for that of Sher Shah in the Purana Kila and the Jamali Mosque at the Kutab.

The gateway leading to the mosque and its Hindu arch are very fine, and the back wall of the mosque, with its open flanking towers, is extremely effective; the decoration of the front may have inspired that of the Mausoleum of Humayun. Half a mile south of the mosque again are the ruins of the citadel of Siri, which now enclose the village of Shahpur Two hundred yards on the way to these ruins is a fine well with an inscription of Sikandar Lodi; and just outside them is a large mosque known as the Muhamdi Masjid, with a single dome.

The north-west defences of Jahanpanah, which connected Siri with Old Delhi, are well seen from here Outside these, and 300 yards west of the Siri wall, is an extremtly picturesque enclosure, known as that of the Makhdum Sabzawar, which well deserves a visit.

The interior, approached by a fine gate in the Hindu style, contains a handsome mosque in the severe Pathan style, but with a red sandstone dripstone, a rest-house, and a tomb covered by a cupola, which still has very beautiful text decoration in plaster inside, and once had fine pierced sandstone grilles all round. The little cemetery is overshaded by fine trees, and is quite one of the prettiest bits near Old Delhi.

Encroachments near and atop historical structures

The Times of India, Apr 17 2016

Building comes up over baoli in Nizamuddin

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has proved incapable of keeping a check on unauthorised constructions in the congested Nizamuddin basti, which houses a number of centrally protected monuments.

A new building is reportedly being built on top of the ancient Nizamuddin Baoli in clear violation of heritage laws.

According to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act, 2010, no construction is allowed within 100 metres of a protected monument. Only controlled construction is allowed after taking the requisite permissions.

The new construction is metres away from the edge of the baoli and is putting extra weight on the structure. The 14th-century baoli, built by Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, is one of the few stepwells left in Delhi that is fed by an active underground spring. The water is considered to possess healing powers and is hence believed to be sacred.

There are a number of tombs surrounding the baoli, which were built around the 17th century . These tombs were later swallowed up by new buildings that were constructed on walls around the baoli.While nothing could be done about these buildings, ASI made it clear that any new construction would not be allowed. However, the new building is coming up right behind one of these tombs. It remains unclear whether the construction has come to ASI's notice or not. Calls to the superintending archaeologist Daljit Singh went unanswered.

“The construction of the building started a week ago ago. Considering the current pace of the construction, it looks like the building will be completed within a month,“ said a local resident.

A few months ago, South Corporation had taken action against an unauthorised building that had come up adjacent to Aga Khan's tomb in the basti. After ASI raised a hue and cry , the corporation demolished the building.

Thursday qawwalis

2018: suspended because of touts

Tourists and devotees turn up at the Hazrat Nizamuddin dargah every evening after the Maghrib prayers for the nightly sama, or music programme. On Thursday, however, they found that no arrangements had been made for the popular Jumehrat qawwali, in which Sufi songs such as ‘Chhaap tilak sab chheeni’ and ‘Aaj rang hai’ fill the air with mystical devotion.

Instead of a session of sung poetry, there was a startling announcement from the dargah committee: the Thursday qawwali would not be held till further notice. The reason for the cessation of the loved activity: some websites and social media groups had begun charging people up to Rs 200 to attend the sama, which has been free for seven centuries.

The decision has left regulars far from happy. Erum Khan, a marketing professional who has been sitting through the sama for 15 years, particularly on Thursdays when it is “especially exciting”, rued that the committee was forced to take such a decision because the “situation has become dire due to touts charging a fee from interested people”.

The qawwalis would be sung as per schedule on other days except on Thursdays. According to dargah committee member Altamash Nizami, a descendant of the saint whose memory is commemorated at the shrine, the decision was taken after “we came to know of several groups promising people, including foreigners, entry into the dargah for a fee”.

Announcing that the committee would file an FIR against all such groups, Nizami added the panel would also send legal notices to anyone who is “cheating the common people and maligning the name of the Mehboob-e-Ilahi”. A notice has been put up on the dargah’s official social media pages cautioning people to be wary of “fake guides and touts”.

The sudden stop to the musical devotion sessions left many disappointed.

“The last time I visited the dargah on a Thursday, a huge crowd had queued up as the qawwals performed some of the most soulful songs I have heard. My second visit has yielding nothing of the sort,” said Charu Dwivedi, a Delhi University student.

Swapna Liddle, convenor of Intach Delhi Chapter, expressed outrage at the thought of people taking financial advantage of the dargah’s Sufi music sessions. She said that Intach accepted payments for taking people on curated walks through the historical quarter, but did not charge them for entry into the mausoleum or for attending the sama.

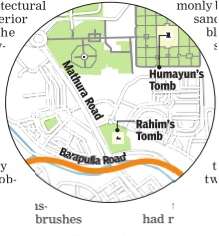

Civic issues

2019- March 20

Abhinav Garg, Nizamuddin: An area in legal strife for long, April 2, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: From being unable to clear parking mess, shut illegal guesthouses, or stop unauthorised construction near protected monuments, the Nizamuddin area has long been in the focus of courts hearing public interest matters.

In the past few years, the Supreme Court and Delhi high court have castigated Delhi Police and the South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC) for major violations in the zone that has world famous monuments like Humayun’s Tomb and the Nizamuddin dargah and tourist attractions such as Sunder Nursery. While most people are shocked that a Covid-19 hotspot emerged in the capital, local activists, lawyers and those familiar with the area see it as something that fits a pattern of violations.

A stone’s throw from the local police station, the roundabout is situated on one of the most crucial arterial road linking central Delhi to east and south districts and sees traffic flow from all directions.

In 2018, the Supreme Court had to point out how encroachers had a field day right under police’s nose as illegally parked autos, bikes and cars blocked even the Nizamuddin police station’s entrance. “At least clear your own backyard,” the SC judges told the police commissioner giving this example while underlining that just outside the building, junked vehicles had become breeding grounds for mosquitos, and were fuelling congestion on Mathura Road and beyond.

Last year, the area was again in focus when SDCM tried to pull wool over the eyes of the Chief Justice of Delhi high court in a PIL filed by the Jamia Arabia Nizamia Welfare Educational Society. Claiming it had taken strict action in removing encroachments and easing traffic congestion, the corporation had shown an empty plastic bottle, ice box, soft drinks trolley, plastic stool and a broken chair as “evidence” of how seriously it took the court’s orders.

A furious then Chief Justice Rajendra Menon directed the SDMC commissioner and the DCP traffic to appear with an explanation. Soon a proper drive was carried out to end traffic congestion on Mathura Road, near Humayun’s Tomb, Neela Gumbad and Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah. They demolished 42 temporary sheds, sealed two illegal kiosks and removed a number of vending carts, iron benches, tables, iron grilles and boards, refrigerators and other articles.

Last year, the local police informed the court that the lieutenant governor had formed a special task force on decongestion and parking in the area. It also claimed to have cracked down on unauthorised guesthouses near the dargah and booked hundreds of vehicle owners for illegal parking. Police had even conceded that they had found 69 illegal guesthouses in the area.

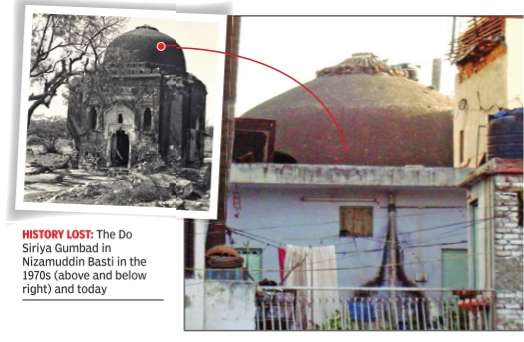

Do Siriya Gumbad

The Times of India, Aug 31 2015

Richi Verma

Rare Pathan-era gumbad now at the mercy of vandals & squatters

When one goes towards Lodhi Road from the Subz Burj roundabout in Nizamuddin, one might spot on the right a large dome peeking from behind buildings. That's the Do Siriya Gumbad, a rare monument from the Lodhiera, now struggling to survive amid attacks from encroachers.

Another monument nearby--the Gol Gumbad-has similar architecture and design, and historians believe the two formed part of the same complex once upon a time. But Gol Gumbad was conserved by Delhi's department of archaeology during the Commonwealth Games in 2010, but this one was left to fend for itself.Experts now fear it may not stand the test of time for much longer with more and more buildings coming up around it.

Do Siriya Gumbad has been occupied by a family for many years who do not allow visitors to inspect the site or even take pictures.While once the area around the gumbad was an open, lush green area, locals from Nizamuddin Basti today have occupied every inch of available space. In fact, the open space once abutting the monument was also taken over by an adjacent hotel about three years ago, and the walls of the southern facade of the tomb have been partially demolished to widen the narrow street.

Conservationists say that until a few years ago, this monument was clearly visible from Lodhi Road. Used as a private residence today , a lot of the original architectural integrity of the monument has disappeared and one can see cracks on the facade and brick masonry topping the original surface.

Overlooked by the Archaeological Survey of India and Delhi archaeology department, Do Siriya Gumbad was listed as a heritage building by the erstwhile MCD.With the main conservation agencies looking the other way , the monument became fair game from squatters.

To salvage the monument, conservationists say that the family residing inside it needs to be relocated, and action needs to be taken against the guest house and other structures built illegally around it.

Do Siriya Gumbad II

The Times of India, Jan 17 2016

RichiVerma

This is the Do Siriya Gumbad, a medieval era monument. The octogenarian Siddiqui has lived his whole life in the fi ve-centuries-old tomb in NizamuddinBasti, as did his grand father and father in the 1940s. It is a miserable existence for a listed heritage building, especially as its counterpart, the GolGumbad in the same co mplex, has been restored to its original glory and maintained by the Delhi government's department of archaeology . But Do SiriyaGumbad, hidden fr om the Lodhi Road, continues to serve as private dwellings for a family that has occupied it for decades. To reach the tomb, you trudge along a claustrophobic lane, wide enough perhaps to allow just two people to walk shoulder to shoulder. Past the brick façade, now denuded of its plastering, you espy an arched doorway , which perhaps was once a grand structure, but today lies decrepit and eroding.

Dolly , one of the residents who ekes out a living as a domestic help, said she and her two small children have no home other than the tomb. “This might be a monument, but we call it home. We have running water and even a metered power connection,“ she says, pointing to an electric meter near the entrance. None of the inhabitants have any idea about the history of their unlikely home.They consider themselves lucky enough just to have a home in the teeming basti. The Siddiquis aren't the only family living in archaeological structures. Many monuments in the historic areas of Delhi--Mehrauli, Chirag Delhi, Zamroodpur, KotlaMubarakpur, among others--are similarly occupied. Many of these buildings are several centuries old and elsewhere perhaps official ignorance of people making homes of such significant structures would leave many aghast. As it is, however, the Siddiques have for neighbours a family living in the crypt of Atgah Khan's tomb, a protected ASI monument. Earlier, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) and the Municipal Corporation of Delhi had provided alternative housing plots to 18 families who had been evicted from their illegal homes atop the HazratNizamuddinBaoli. Siddiqui and his clan are likely to offered similar amenities.

In December 2015, Delhi Development Authority (DDA) cleared 200 square yards on the approach to Do SiriyaGumbad of encroachments.

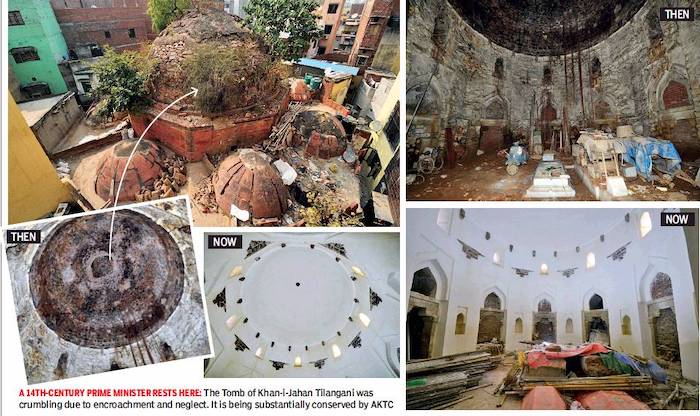

Khan-i-Jahan Tilangani mausoleum

The 2019 restoration

Richi Verma, June 3, 2019: The Times of India

From: Richi Verma, June 3, 2019: The Times of India

Encroached Tughlaq-era tomb gets new lease of life

New Delhi:

The earliest octagonal tomb in India is a forgotten monument in the heart of Delhi. But 700 years after it was made, it is getting a new lease of life.