Delhi: Qutub Minar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Qutub Minar: a 1902, British account

This section was written between 1902 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

Extracted from:

Delhi: Past And Present

By H. C. Fanshawe, C.S.I.

Bengal Civil Service, Retired;

Late Chief Secretary To The Punjab Government,

And Commissioner Of The Delhi Division

John Murray, London. I9o2.

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to the correct place.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

There is no good reason for doubting that Kutab-ud-din-Aibak began the basement storey

of the Kutab Minar—the name of the minaret in common parlance is much more probably

derived from him than from the saint known as the Kutab Sahib,—any more than there is for

doubting that it is entirely of Muhammadan origin, and was primarily intended to serve as a

minaret to the mosque of that Sultan.

The last is clear, not only from almost contemporary record, but also from the text from the Koran, cap. 62—The Assembly—on the second storey “Oh true believers, when ye are called to prayer on the day of Assembly, listen to the commemoration of God and leave merchandising. . . . The reward of God is better than any sport or merchandise, and God is the best provider.”

The lowest storey contains an inscription bearing the name of the first King of Delhi, and two others containing the name of his master, Muhammad-bin-Sam, or Muhammad Ghori; the second and third and fourth storeys bear bands of inscription with the name of Altamsh; and the fifth storey one relating to a restoration in 1368 A.D. by Firoz Shah, who, no doubt, entirely rebuilt the two topmost storeys of their original materials. On the entrance door to the Minar, which is modern, as is the railing of the first gallery, is an inscription of the year 1503 A.D., recording a restoration by Sikandar Shah Lodi, which probably preserved the Minar till 300 years later, when it was thoroughly repaired by the British Government, only just in time apparently, to judge from Major Thorn’s narrative of the events of 1803.

The value of this restoration must not be lost sight of in the ridicule which has overtaken the officer in charge of the work, a certain Captain Smith, R.E., in connection with the cupola designed by him for the summit, and which still stands in the Kutab grounds. (Colonel Sleeman wrote, not unjustly, of this: “If Captain Smith’s storey was anything like the original, the lightning did well to remove it !”) One would have been disposed to believe that the original topmost storey was a simple pavilion borne by four, or possibly eight, arches—very likely flat Hindu arches—but this is not borne out by the drawings of the column in Franklin’s book and by Daniell, though Ensign Jas. Blunt, who visited Delhi in 1794, says it was “crowned by a majestic cupola of red granite.” It would add greatly to the effect of the column if a suitable cupola could be placed upon it.

The height of the Kutab Minar is 238 feet, and of the first gallery 95 feet. The lowest storey has twenty-four flutings alternately round and angular, the second has only rounded flutings, and the third only angular. The line of each fluting is carried up unbroken through each storey, and this adds greatly to the effect of the tower.

The parapet of the first gallery appears to have been of a simple crenellated battlement form; the arrow-head pattern in the upper galleries is said to exist also in the Kalaun Mosque of Cairo. The outline of the column is not at first very pleasing to eyes accustomed to Gothic towers and spires, and from a distant point of view seems perhaps less graceful than when seen from nearer.

But of the beauty of the warm colour of the stone, of the splendid bands of texts and ornamentation which encircle it, and of the work on the under sides of the galleries, there can be no question.

The lower bands 1 of inscription can be well seen from the top of the south-east corner of the Kuwat-ul- Islam Mosque and the Alai Gate; while charming views of the column as a whole are obtained in framings of the centre arch of the mosque screen and of the last of Altamash’s arches to the south, and other beautiful glimpses from every side will be enjoyed by those who have time to wander round the outskirts of the general enclosure.[ 1 The six bands of inscription in the basement storey contain: first, the designation and title of Kutab ud-din; second, the titles and praise of Muhammad-bin-Sam; third, a verse from chapter 59 of the Koran; fourth, another recital, as in the second band; fifth, the ninety-seven Arabic names of the Almighty; and sixth, a verse from the Koran, The verse regarding the call to prayer is on the second storey.]

For the rest, it is again sufficient to quote what Mr Fergusson writes in this connection: “It is probably not too much to assert that the Kutab Minar is the most beautiful example of its class known to exist anywhere.1 The rival which will occur at once to most people is the Campanile at Florence, built by Giotti. That is, it is true, 30 feet taller, but it is crushed by the mass of the Cathedral alongside; and beautiful though it is, it wants that poetry of design and exquisite finish of detail which marks every moulding of the Minar.”

It will interest many to note the plumb line of the tower on a stone in the south side of its basement.

The number of steps to the top of the Kutab is 379. The view from there is very striking, but is practically as extensive from the first gallery. At the foot of the column are seen spread out the mosque and all the buildings which surround it. A little further off lie the encircling lines of the defences of Lal Kot, and Kila Raí Pithora rising highest to the west, and bounded there by the dark wall of the heavy Idgah of Old Delhi.

Across the plain north of Rai Pithora’s fort may be traced the Jahanpanah embankments, running towards the ruined walls of Siri, which do not, however, show up from here; the massive dark block of the Begampur Mosque, however, indicates their position. Above Jahanpanah, and to the north-west rises the depressed pale dome of the tomb of the Emperor Firoz Shah in Hauz Khas, and beyond it the bright pointed dome of Safdar Jang’s tomb, and almost in a line with it the still brighter domes of the Jama Masjid of Delhi.

To the east of Safdar Jang appear the long wall defences of the Purana Kila, with the low white roof of Nizam-ud-din, and the high marble dome of the Emperor Humayun’s tomb below them. South of these again is the popular Kalka temple on the rising ground, and below this, and nearly due east of the Kutab, are the fortresses of Tughlakabad and Adilabad, with the low white dome of Tughlak Shah’s tomb between them. Nearer and to the north of the road to Tughlakabad are the large groves of trees which mark the Hauz Rani and Khirki, while south of the road and close to the Kutab are the Jamáli Mosque and the lofty ruins of the tomb of the Sultan Balban, and under it on the south the Dargah of the Kutab Sahib, and the houses of Mahrauli half hidden in trees.

The Qutub, over the centuries

Historical photographs

See graphic:

How Qutub stood tall in Mehrauli over the centuries

Richi Verma

From: The Times of India

It's the monument that witnesses the maximum footfall in the national capital, and now visitors to the Qutub Minar will get a chance to see how it evolved through the centuries. To commemorate World Heritage Week in Delhi, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) will be hosting an exhibition of rarely seen, archival images and sketches of Qutub Minar dating back to as early as the mid-19th century .

The exhibition will be held in the Qutub Minar lawns. Officials said that out of a collection of over a 100 images from reference books and archival compilation, they shortlisted about 85 to be displayed in the exhibition that will be opened for the public on Wednesday . Depending on the response it gets from visitors, it may be extended beyond the week-long World Heritage Week celebrations ending on November 26.

Padmashree awardee RS Bisht, former joint DG of ASI and renowned archaeologist, will inaugurate the exhibition. “Each image will be accompanied with a caption and short write-up. The selected images show Qutub Minar in the backdrop of 19th century Delhi when most of the surrounding buildings present to day did not exist. It will help visitors see how the surroundings evolved through the decades,“ said officials.

Last year, the World Heritage Week focused on Red Fort. “In 2013, we held an exhibition on the forgotten monuments of Delhi at Red Fort. This year, the focus is not just on Qutub Minar but all the monuments located in Mehrauli and surround ing areas. Mehrauli is archaeologically rich and we want to raise awareness about its heritage. Most people just visit Qutub Minar and then head to other places. But there is much more to see here, from the monuments of Mehrauli Archaeological Park to Zafar Mahal, Adham Khan's tomb, Lal Kot, etc,“ said officials.

Qutub Minar will be the first monument in Delhi where ASI will be installing a board detailing information and locations of other monuments in the vicinity .The first board will list Quli Khan's tomb, Jamali Kamali, Gandhak ki Baoli, Jahaz Mahal, Balban's tomb, Jharna, etc. “The boards will give details and history of these monuments and also directions on how to get there,“ said an official.

In days to follow, five other monuments -Red Fort, Humayun's Tomb, Purana Qila and Safdarjung Tomb -will also have similar boards.

The 2018 touch- up

From: Richi Verma, Qutub Minar gets touch-up after 50 years to protect it from bird, bat poo, June 30, 2018: The Times of India

From: Richi Verma, Qutub Minar gets touch-up after 50 years to protect it from bird, bat poo, June 30, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

The Archaeological Survey of India has replaced crumbling doors and cracked windows in each of the four balconies with wood-frame jaalis and iron grilles.

The project would cost about Rs 8 lakh, and this, ASI thinks, would stop the entry of birds and bats.

For centuries, it weathered earthquakes, hailstorms and many other troubles. It stood tall even in the face of invading armies. But the mighty Qutub Minar has been humbled by bird poo.

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has, for the first time in over 50 years, replaced crumbling doors and cracked windows in each of the four balconies with wood-frame jaalis and iron grilles. The project would cost about Rs 8 lakh, and this, ASI thinks, would stop the entry of birds and bats.

2 The project would cost about Rs 8 lakh, and this, ASI thinks, would stop the entry of birds and bats.

Over a period of time, doors and windows had developed cracks, allowing winged creatures to enter. At first, the bird and bat droppings were taken just for their nuisance value. But soon, it became a matter of grave concern as officials were cleaning piles of droppings. "The droppings not only made the interiors of the monument unhygienic, musty and foul-smelling, but also affected the precious stones," said N K Pathak, superintending archaeologist, ASI (Delhi circle).

4 The Archaeological Survey of India has, for the first time in over 50 years, replaced crumbling doors and cracked windows in each of the four balconies with wood-frame jaalis and iron grilles.

After careful measurements, the new frames were installed. "The work has been going on for nearly three months. The new frames are being made in Qutub complex itself," said an official.

5 Over a period of time, doors and windows had developed cracks, allowing winged creatures to enter.

Historians say the minaret had doors at each opening, but it's unknown what the original doors were like. But surely, these could be opened and closed. There are several small and large windows inside the minaret to allow light and air circulation. In the 1950s, the ASI had installed new doors, which outlived their utility. The ones being installed now are fixed and will stay closed for most of the time.

7 Bird poo at heritage buildings worries conservationists as these contain acids. "These can cause a lot of damage to ancient building surfaces, resulting in the scarring of building fabric and damaging of appearance. The corrosive effects can continue for a long time after a stone is contaminated," said an expert.

Why the Qutub is closed

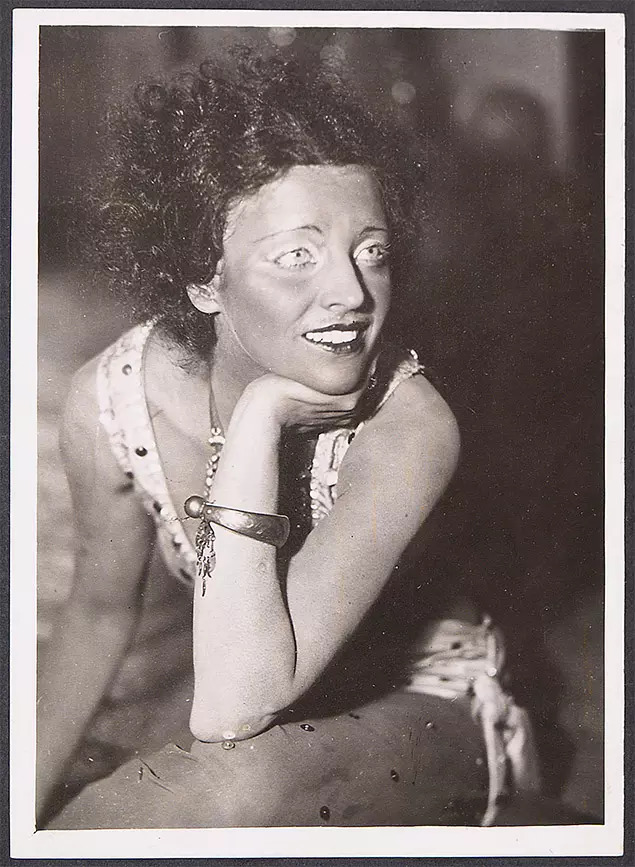

Rani Tara Devi (Eugenia Marie Grosupova)/ 1946

Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

By December 1946, the tall, slim woman with the wide-set eyes was a familiar sight at New Delhi’s Maidens Hotel. She had been staying there for about a month. Every day, she took her dogs out walking. But on the morning of the second Monday – December 9 – she came out of her suite alone, hailed a taxi and sped towards the Qutub Minar.

It was a long drive, the 13th-century tower – Delhi’s tallest building until then and for many years afterwards – lay outside the capital, about 20km away.

On arriving at the Minar, the woman left her handbag with the driver and started up the stairs. She must have been gone many minutes because the tower is over 72 metres tall – taller than a 20-storey apartment building – and not an easy climb even for someone in fine fettle.

The waiting driver might have stood leaning against his car, head bent backwards to see her emerge in one of the Minar’s balconies. He couldn’t have seen the look on her face when she appeared at the very top, breathless perhaps. But then, he would have frozen in shock as she jumped to death.

The Minar’s diameter grows from 9 feet at the top to 47 feet at the base. Some accounts say she fell on the edge of the second balcony. But newspaper reports of the day say her body was found at the base of the Minar.

A woman so beautiful that she had wowed Vienna’s elite on her first major stage appearance 11 years earlier, now lay smashed beyond recognition. Who was she? The contents of her handbag revealed she was Rani Tara Devi, the 33-year-old estranged wife of Kapurthala’s ageing maharaja, Jagatjit Singh.

After a post-mortem next morning, Tara Devi was buried at the Nicholson Cemetery near Kashmere Gate in Delhi, and forgotten.

A charmer on stage

But Tara Devi wasn’t her real name. Before the maharaja married her sometime in 1941 or 1942, she was just a foreign national staying in India as his guest. A Kapurthala state declaration submitted to the British in 1940 mentions her name as Engenie Marie Grosupova, which might have been a typist’s mistake. Eugenie is the more likely name.

The rani was a Czech national, born on January 22, 1914. Before accompanying the maharaja to India shortly before WW-II started, she had been a promising new dancer on Vienna’s most famous stage, the Burgtheater.

In his book ‘Maharani’, Diwan Jarmani Dass, who claimed to have been a minister in the royal families of Patiala and Kapurthala, says she was the illegitimate daughter of a Hungarian count. Dr Leon Pistol, who had been her guardian in Vienna from the age of 4 to 20 years, also hinted at this when he told the Canadian paper ‘Photo Journal’ that she was the daughter of “a very wealthy member of the Hungarian nobility”.

In 1935, Eugenie had landed a meaty role as Anitra in the drama Peer Gynt. She made at least two appearances, on June 8 and September 3 that year, and both times the press admired her for her beauty, femininity and dancing.

Austrian papers such as Die Stunde mentioned her as Nina Grosup-Karatsonyi. After her suicide, papers in America, Europe and Australia also used the name Nina Grosup, so did Pistol. So, Nina is what we’ll call her for the rest of this story.

A royal romance

After making a splash on the stage in 1935, Nina disappeared from it swiftly. In April 1947, four months after her suicide, Pistol told Photo Journal that the maharaja had been present at the Burgtheater during one of her performances. “Immediately after the performance, Nina’s mother called me to tell me that the maharaja wanted to bring them all back (to India) with him,” the article written in French says.

Another article published in the Sydney edition of The World’s News on August 23, 1947 also says, “On the opening night she received an ovation from the crowd, and a huge bouquet of roses from the maharaja of Kapurthala, who had been admiring the dancer from his box.”

Pistol said he opposed the maharaja’s offer because Nina had signed a three-year contract with the Burgtheater, but “the suitor-royal simply shrugged his shoulders and offered to buy out the contract in question for $20,000.”

Soon after this, Nina, her then 46-year-old mother Marie Grosupova, and a 64-year-old maid/governess named Antonia Kaura, “followed the Maharajah to Paris, London, and finally, to India”.

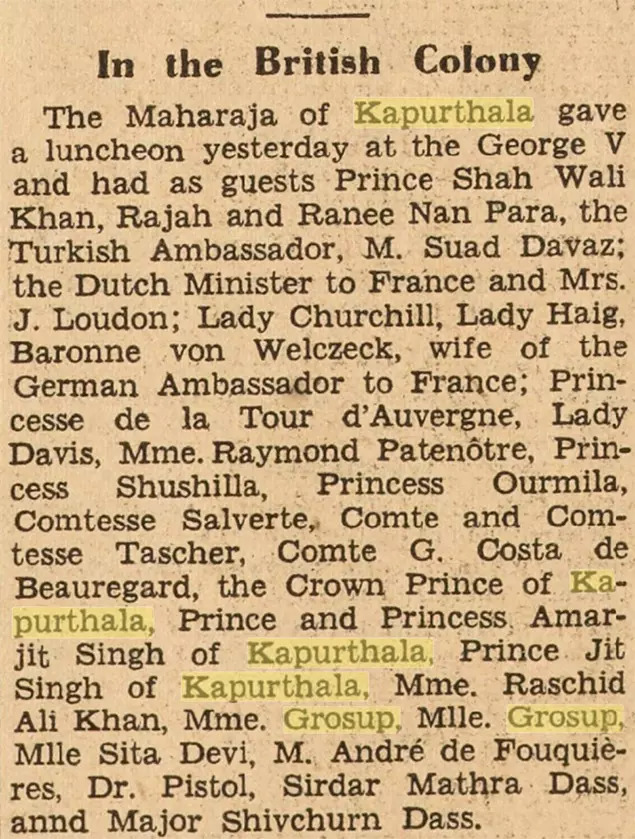

It’s difficult to verify Pistol’s claims in detail but the International Herald Tribune of June 28, 1938 describes a luncheon hosted by the maharaja at the George V hotel in Paris at which ‘Mme Grosup’ (Marie), ‘Mlle Grosup’ (Nina) and ‘Dr Pistol’ were among the guests. Clearly, Pistol’s story had a kernel of truth.

By the time WW-II started late in 1939, the Grosups and their maid were already installed at the Jagatjit Palace in Kapurthala. Nina and the maharaja weren’t married but Dass says the 67-year-old ruler was lavishing all kinds of expensive gifts on the 25-year-old former dancer. There must be some truth to this also as after her death, her possessions in the hotel suite were valued at many thousands of dollars.

When in February 1940, the British government asked the princely states to submit a list of ‘enemy subjects’ residing in their territory, Kapurthala declared the Grosup women (Czechoslovakia was under German occupation) were “guests of his Highness the Maharaja of Kapurthala”. Unhappy marriage

The maharaja was well-known in Europe and America and his engagements were regularly covered. Whole pages were written about him, so strangely his marriage to Nina doesn’t find a mention abroad. It’s true the press’s attention was occupied by the war, but still to ignore one of their favourites in this manner seems odd. Maybe, the maharaja deliberately kept his sixth marriage low-profile, but it is a fact that Nina and he were married, and she was given the Indian name Tara Devi, because the question of “the grant of a British passport to Rani Tara Devi (formally Miss Grosup, a Czechoslovak citizen) wife of His Highness the Maharaja of Kapurthala” did come up in 1942.

It seemingly wasn’t a happy marriage for both parties. News reports after her suicide said they had separated in 1945 and Nina had been living alone. Pistol said she had even intended to visit America in December to settle there. The World’s News article said she had asked Pistol to buy her a house near New York City.

But much as she wanted to, Nina could not leave India. News of her death was covered well abroad but played down in India. The Madras edition of a prominent paper put it on its second page, below “Madras-Colombo rowing contest postponed,” and “Beedi workers’ strike in Malabar & S Kanara”.

Suicide or murder?

From the very first, Pistol said he suspected foul play in Nina’s death. He alleged that a month before she died, she had written to him saying, “Every day when I go out with my dogs somebody is asking me questions and follows me. I don’t know what he wants. I think it’s someone – a detective. But don’t worry.” She had also been jittery since her mother’s “mysterious death” a year earlier.

Pistol claimed Nina had left behind a fortune amounting to $150,000, including at least $100,000 in jewellery, “40 coats of furs and 52 trunks full of clothes”, all of which were his to inherit. “I will not rest as long as it is not clear whether the mother and governess died of natural causes and the maharanee committed suicide, or whether all three were murdered,” he is quoted in The Bombay Chronicle of September 22, 1948.

The National Archives of India has a record of an “Enquiry by Mr Leon Pistol, guardian of late Rani Tara Devi of Kapurthala, regarding her death in 1946,” filed in 1948. Four years later, in 1952, Pistol also sent a request to the PM “for assistance and advice regarding investigation into the mysterious death in 1946 of Eugenie Grosup, popularly known as Rani Tara Devi of Kapurthala.” But by then, the maharaja had died and the rani, whom few knew while she lived in India, lay completely forgotten.

The 1981 tragedy

Abhilash Gaur, Nov 15, 2021: The Times of India

From: Abhilash Gaur, Nov 17, 2021: The Times of India

Long ago, you could climb to the top of Delhi’s Qutub Minar. In the early 1850s, British agent Thomas Metcalfe’s daughter Emily used to take “a basketful of oranges to the top of the Kutub Minar, 283 feet high, to indulge in a feast in that seclusion” (her papa disapproved of women eating cheese, mangoes and oranges; and she got the minar’s height wrong – it’s 238 feet).

A century later, the tower was still open. Football lore has it that Delhi owes its lone Santosh Trophy triumph, in 1944, to the Qutub. On the morning of the final, a Delhi official allegedly took the visiting Bengal side sightseeing to the minar, and told them it was impossible to climb its 379 steps without a rest. Six Bengal players trudged upstairs to prove him wrong. They returned with legs so sore that Delhi beat Bengal 2-0.

The free run ended a few years later because of all the suicides that happened at the Qutub. One of the more sensational cases was that of a rani of Kapurthala – a Czech woman named Nina Grosup, a.k.a. Evgenia Grosupova and Tara Devi – who jumped to her death in December 1946. So, in the early 1950s the government barred access beyond the minar’s first balcony. It did not affect the suicide rate, though, because even the first balcony is as high as a 10-storey apartment building.

Picnic turns calamity

Like any other Friday, December 4, 1981 was a very busy day at the minar. Entry to the Qutub compound used to be free on Fridays then, and there was no ticket for going up either, so schools and colleges scheduled their Qutub picnics for Friday mornings. It was the last time the general public saw the monument from inside. By 11am, busloads of students and other visitors were inside the spiral staircase that leads up to the minar’s first balcony. By all accounts – even the government admitted – there were far more visitors than could be safely accommodated.

Around 11.30am – reports from that day say – there was a power failure, and the lights inside went out. The minar has large vents at regular intervals for air and light, but as the visitors who were close to the outer wall pressed against it for safety, they cut out the daylight. Then, as the scared crowd tried to exit desperately, a stampede occurred. Within minutes, dozens of people lay dead and injured in the darkness.

Anil Kumar, a student of Delhi’s Aurobindo College at the time, was inside the minar with seven of his friends when the stampede occurred. He told TOI they were descending the dark stairs in single file when they suddenly “found themselves sliding down uncontrollably”. He survived with chest injuries.

Manjulal, a two-year-old boy from Faridabad, was probably the luckiest visitor. He had come to the minar with his parents Vimla Rani and J P Gulati. As chaos erupted, he “glided over hundreds of wailing and screaming people in the dark stairs...and landed outside without any injury after being passed on from hand to hand,” TOI reported.

Trapped behind jammed doors

The minar gate had heavy steel doors that opened inwards. As the number of people inside swelled, the chowkidar had pulled the doors shut. When hundreds of people tried to barge outside at once, the doors jammed against the frame. Rescuers couldn’t enter through the gate because of the mass of people behind it. Fortunately, a scaffolding had been built behind the minar to carry out repairs, and local hawkers and tourist guides used it to enter the minar through the vents in the outer wall. They extricated many survivors and bodies over an hour. Some Sikh youths undid their turbans and used them to lift buckets of water for the shocked survivors inside.

By the time police and the fire brigade arrived, the dead had been laid out in the Qutub lawns and the injured rushed to Delhi's AIIMS and Safdarjung hospitals in the tourist buses that had brought them in the morning. At 3.30pm, then home minister Giani Zail Singh informed Lok Sabha that 45 persons had been killed and 21 injured.

Journalists who looked inside the minar after the evacuation reported seeing books, sweaters, cameras and handbags everywhere. These were piled up at the minar gate in the evening. The Times of India of December 5 reported: “The sides of the staircase were splattered with blood as people were ruthlessly battered against the solid walls.”

A team of 12 doctors formed to do the autopsies finished its work around 1.30am on December 5. They attributed most of the deaths to suffocation and trampling, not bleeding. Few corpses had external injuries.

What caused the stampede?

The pitch dark minar must have made the people nervous, but that alone would not have started a stampede. Survivors that day gave different accounts of what had happened. Some said a group of unruly boys had misbehaved with women tourists in the dark, and the stampede started when those women tried to rush downstairs. Others said someone had slipped in the dark, and set off a chain reaction while trying to regain balance. Some said there had been a scuffle when thieves tried to pick pockets in the dark, and that had led to the stampede.

A tragedy waiting to happen

Next day, New Delhi additional commissioner of police Nikhil Kumar denied receiving any complaint of molestation, but news reports from the time say two tourists from New Zealand, Jackie and Marie, had alleged they were molested. One of them was seen leaving the Qutub compound wearing a borrowed lungi and shirt. Later, district and sessions judge Jagdish Chandra’s inquiry report in the case also made a mention of their harassment.

In the Rajya Sabha, the Opposition alleged police protection and political patronage to “local goondas” had caused the tragedy, but molestation inside the minar wasn’t a new thing. Twenty-four years earlier, on November 21, 1956, an MP had asked then deputy education minister Dr M M Das (the archaeology department used to be under the education minister) in Lok Sabha if he knew women were molested and pockets picked in the minar’s “dark and dingy passage”. The minar lacked electric lights those days, and the minister had replied they weren’t needed as the minar had “been like that for 750 years”.

Overcrowding was also an old problem, especially on holidays. There had been another stampede inside the minar on August 15, 1978 when a man had fainted from suffocation in the packed staircase. Twelve people were injured that day, six of them seriously.

After the December 1981 tragedy, education minister Sheila Kaul told Lok Sabha a system of crowd-control had been in place since the 1950s, when tickets were introduced at the Qutub. There are 155 steps up to the first balcony, so 300 visitors were allowed in at a time. They walked up single-file, looked around from the balcony, which had space for 40-50 persons, and then descended single-file. When 50 visitors exited the tower, 50 more were sent inside.

Ensuring that the tourists ascended and descended the steps – which are about 5 feet wide at the base and narrow to 4 feet at the balcony – in an orderly double spiral was crucial for safety, but on Fridays and other holidays this was impossible. By some accounts, more than 500 people were inside the minar on December 4, 1981. Kaul initially said the stampede had occurred because about 60 boys from a college in Nuh, Haryana had barged into the minar disregarding the chowkidaar’s warning about crowding.

‘Qutub is falling…’

Just as the police denied reports of molestation, the Delhi municipal corporation at first said there had been no power outage at the minar between 10.50am and 12.30pm on December 4. A truck had dashed against an electricity pole, tripping power at 9.15am but supply had been restored by 10.50am, it said. But the 49-page Chandra Commission report found power failure to be one of the major causes of the tragedy, and held Delhi Electricity Supply Undertaking (DESU) responsible for it.

The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) was held equally culpable for the “very bad and dangerous condition” of the steps. The steps had “dangerous depressions and contours” because they had never been repaired, it said.

The inquiry commission concluded that while the girls from New Zealand had rushed downstairs to escape the molesters, the real stampede had occurred when another girl had slipped near the minar’s 8th ventilator and some boys had raised a false alarm: “Qutub is falling...go down, go down.”

This account agrees with what B D Singh, MP from Phulpur in Uttar Pradesh, told Lok Sabha on December 7, 1981. He had visited the minar on the evening of December 4 and found that all the casualties had occurred roughly between the 40th and the 60th steps.

Will it open again?

The Chandra Commission had recommended better lighting inside the minar, paid entry and restricting access to 100 people at a time. It had also asked ASI to repair the minar’s steps before reopening it. The repairs were made over a year, and in 1983 ASI proposed reopening the minar to visitors but the government declined.

Twenty years later, Prime Minister A B Vajpayee’s culture minister Jagmohan directed ASI to open the minar up to the third storey, but this time the agency said the steps above the first storey would need repairs. The minar remains closed, and it seems unlikely that it will ever open again.

Photos: Abhilash Gaur, Ajay Kumar Gautam, Piyal Bhattacharjee

See also

Delhi: Qutub Minar