Medical education and research: India

(→Capitation fees gone; private colleges’ fees zoom up/ 2016) |

(→Fees) |

||

| Line 643: | Line 643: | ||

(Put together by TOI's network of health reporters across India) | (Put together by TOI's network of health reporters across India) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2021=== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/quota-for-the-rich-28-of-mbbs-seats-cost-over-rs-10-lakh-per-year-in-tuition-fees/articleshow/81371223.cms Rema Nagarajan, March 7, 2021: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

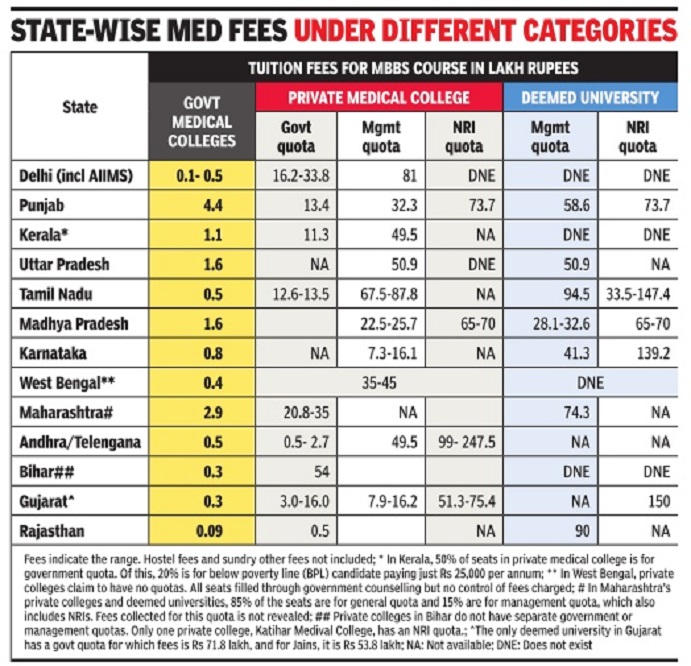

| + | [[File: States where tuition fee is over Rs 10 lakh per year, 2021.jpg|States where tuition fee is over Rs 10 lakh per year, 2021 <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/quota-for-the-rich-28-of-mbbs-seats-cost-over-rs-10-lakh-per-year-in-tuition-fees/articleshow/81371223.cms Rema Nagarajan, March 7, 2021: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Quota for the rich? 28% of MBBS seats cost over Rs 10 lakh per year in tuition fees ''' | ||

| + | |||

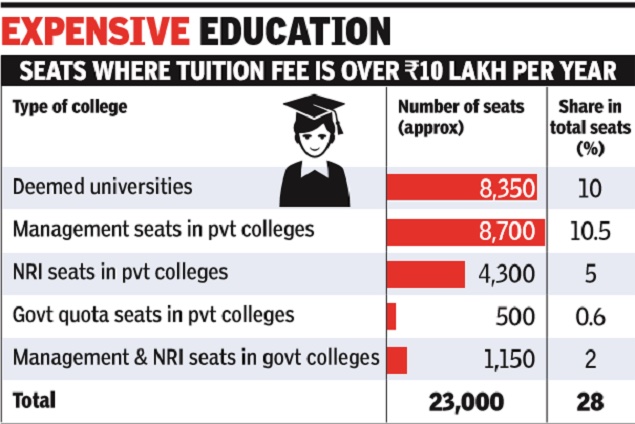

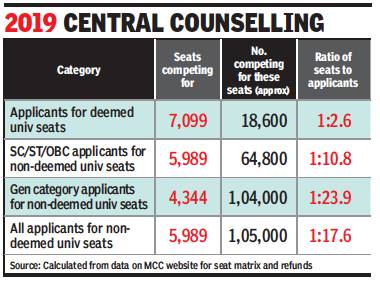

| + | About 28% of MBBS seats in India cost over Rs 10 lakh per annum in just tuition fees. The high fees effectively makes these seats a quota for the rich, one that is larger than those for the SC (15%), ST (7.5%) or OBC (27%). And that’s without taking into account the fact that this 28% is of total seats, while the caste-based reservations do not apply to all. | ||

| + | |||

| + | How did we get to this 28%? It’s based on a detailed analysis of fees for the MBBS course in over 530 MBBS colleges. About half the seats in private colleges, excluding deemed universities, are in the management quota or NRI quota. In the NRI quota, the average annual tuition fee is roughly Rs 25 lakh per annum. For the management quota, the average fees are around Rs 11 lakh though it varies from Rs 4 lakh in private colleges in West Bengal, which is uncommon, to Rs 18 lakh to Rs 20 lakh in states like Karnataka and Rajasthan. Besides the tuition fees, almost all colleges collect about Rs 2 lakh a year as charges for hostel, mess, exams, library and so on. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The most expensive seats are in the deemed universities. Over 8,500 seats in these universities constitute about 10% of all MBBS seats. Barely 3% or about 23,000 of the 7.7 lakh who qualified through the combined entrance exam, NEET, applied for these seats. The average annual tuition fees for NRI seats in these colleges are Rs 36 lakh, which is about Rs 1.6 crore for the entire course. The average fees for management seats in them are Rs 18 lakh. | ||

| + | |||

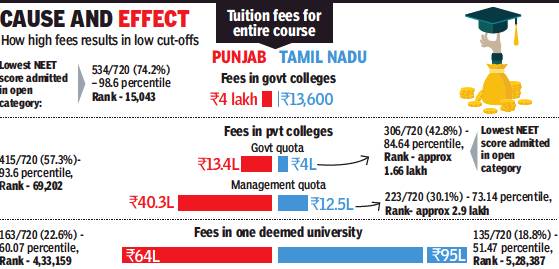

| + | TOI had reported earlier how the higher the fees, the poorer the average NEET score. The high fees leading to a virtual reservation for the rich has led to those with ranks even below 6 lakh in NEET getting admission, though there are only about 83,000 MBBS seats. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even some government colleges, mostly in Gujarat (11 colleges) and Rajasthan (8 colleges) have management seats (1,350) and NRI seats (580) at an average Rs 18.5 lakh. The management quota seats in these government colleges range from Rs 7.3 lakh to Rs 18 lakh per annum in some of Gujarat’s municipal medical colleges in Gujarat. Others could also be as low as Rs 75,000 in Rajasthan to Rs 1 .3 lakh in Doon Medical College in Uttarakhand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most states governments have been pushing up fees in their medical colleges citing the high cost of medical education, though the money collected from increased fees is just a fraction of the budget. In Punjab, the cost of MBBS in government colleges went up from Rs 4.4 lakh to Rs 7.8 lakh, among the highest in the country. Fees in most government colleges in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh are about one lakh per year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Incidentally, according to the latest expenditure survey done by the NSO in 2017-18, before the job loss of millions and economic devastation caused by the pandemic, the monthly expenditure of 80% of Indian families was less than Rs 10,500. Renowned economist Thomas Picketty had estimated that in 2015 about 5% of Indian adults earned over 63,000 a month or over 7.5 lakh a year. He estimated that just 1% (13.8 million) earned over 2 lakh. This is unlikely to have changed much since. What this means is that at best only 5% of families can afford the fees being charged for medical education in most institutions, even government ones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fifteen AIIMS accounting for about 1,100 seats offer the cheapest medical education, mostly charging Rs 1,628 or Rs 5,856 per annum. Centrally-funded institutions charge the least fees. West Bengal and Bihar offers the cheapest medical education in the country with the majority of colleges in the former charging Rs 9,000 as tuition fee and Rs 144 as hostel fees and the latter charging about Rs 6,000 as tuition fees and Rs 4,200-20,000 as hostel fees. Even among private colleges, West Bengal has among the lowest fees, mostly well below Rs 5 lakh for management seats and about Rs 15 lakh for NRI seats. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2016, the Parliamentary Standing Committee report on the functioning of the Medical Council of India (MCI) and medical education had strongly criticised “admission procedures which are primarily monetary based”. The committee recommended a common entrance test “to ensure that merit and not the ability to pay becomes the criterion for admission to medical colleges”. But with fees remaining unchecked, neither the new National Medical Commission nor the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET) has achieved this. | ||

[[Category:Bangladesh|MMEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH: INDIAMEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH: INDIA | [[Category:Bangladesh|MMEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH: INDIAMEDICAL EDUCATION AND RESEARCH: INDIA | ||

Revision as of 21:13, 7 March 2021

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

All-India quota in deemed universities, govt. medical colleges

2017, May: To be filled by DGHS: SC

The Supreme Court has ordered that the all-India quota in deemed universities and government medical colleges will be filled by the director general of health services (DGHS) in New Delhi. This will include deemed universities run by religious and linguistic minorities too as these institutes have an allIndia character.

The quota is 15% for UG courses and 50% for PG courses. Till the year before last, deemed universities conducted their own exams and admitted all students.Last year, after losing a case in the SC in the middle of the admission process, they admitted students based on NEET rankings.

Common counselling for state quota seats in government and private medical colleges, including colleges institutions run by religious and linguistic minorities affiliated to state universities, shall be conducted by the state government or the authority designated by the state government. Moreover, state governments must conduct two rounds of centralised counseling for the all-India quota and process the admission too on behalf of deemed universities and private colleges.

The apex court has ruled that cheques for tuition fees should be collected by the state's admission-conducting body so that colleges do not state that candidates weren't turning up. After the second round of counselling for all-India seats, students who take admission should not be permitted to vacate them, the SC said.

“This would ensure that very few seats are reverted to the state quota and also allIndia quota seats are filed by students from the all-India merit list only. The students who take admission and se cure admission in deemed universities pursuant to the second round of counselling conducted by the DGHS shall not be eligible to participate in any other counseling,“ the SC ruled in a writ petition filed by Dar-us-salam Education Trust against the MCI.

The notification to be is sued by the state notifying the common counselling should also provide the fee structure of deemed universities and private medical colleges, as per the SC directive. “The students who secure admission in MBBS course pursuant to the common counselling conducted by the state government, should be made to deposit with the counselling committee the demand draft towards the fees payable to the institution. The admission counselling committee shall forthwith forward the demand draft to the respective institutioncollegesuniversity. The necessity for including the above-mentioned requirement has arisen as it has been time and again noticed that when students report to the college after the counselling they are refused admission by the colleges on some pretext or the other and it is shown by the college as if the student never reported to the college for admission.“

2017, Aug: 50% MBBS; 85% BDS seats at these institutes vacant

`Up to 12k seats may remain vacant', August 24, 2017: The Times of India

BDS Vacancies 85%; Admissions End On Aug 31

Deemed universities and private colleges across the country are staring at a huge crisis of unfilled undergraduate medical seats under the new system of centralised counselling introduced under the Supreme Court's orders this year.

As the third round of counselling comes to an end on Thursday , more than 50% of MBBS seats and almost 85% of dental seats in these institutes are still vacant.

The final mop-up of vacant seats is scheduled for August 28 (after 5 pm) and the admission process comes to an end on August 31. These institutes fear that a majority of their seats will remain unfilled as, under the new rules, these universities will not be allowed to admit students on their own.

Sources said even in government colleges nearly a third of the 15% seats under the all-India quota has remained vacant till now. However, unlike deemed universities and pri vate colleges, government institutions will get a chance to fill these seat as these will be transferred to the states. A senior health ministry official said the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), which is conducting the counselling, will seek legal opinion on how to resolve the crisis of unfilled seats.

While this may come as a ray of hope for medical aspirants, what is troubling the deemed universities is the new matrix of counselling, under which these institutes will have to go by the DGHS list even after the final transfer of seats. According to the head of a private medical col lege in Karnataka, “We have 200 MBBS seats, of which 30 are for NRIs. In this category, we have filled just one seat.Of the 170 general seats, 89 have been filled after DGHS counselling till the mop-up round. In BDS, we have filled 29 out of 100 seats.“ There are deemed universities where no admissions have taken place till now.

“After the mop-up round, which is getting over tomorrow, the seats will be transferred to the deemed universities. And for every 10 vacant seats, DGHS will release a list of 100 candidates (10 times higher). But when a similar process during the first three rounds has yielded next to nothing, we expect less than 10% of the vacant seats to be filled. Till last year, deemed universities had the option of choosing their students,“ said the vicechancellor of a deemed university in Hyderabad.

The admissions are being conducted based on NEETUG, 2017. “The counselling has been undertaken as per the apex court's order and guidelines, and no changes are possible to tackle the issue of unfilled seats. We are going to seek legal opinion and also approach the court again. Otherwise there is a possibility of up to 12,000 seats remaining unfilled this year,“ said a senior DGHS official.

Colour blindness

SC appoints expert committee to redefine bar

AmitAnand Choudhary, SC: Colour-blind ban for MBBS regressive, Mar 26 2017, The Times of India

Can a student suffering from colour blindness be allowed to pursue medical courses?

The Supreme Court has agreed to consider a plea of two students to open the door of medical colleges for them, saying the present practice of Medical Council of India not permitting colour-blind students to take admission in MBBS courses is regressive and should be done away with.

A bench of Justice Dipak Misra and Justice A M Khanwilkar appointed an expert committee of senior doctors to find out streams in which such students could be allowed. It said students with colour blindness were allowed to study medical courses in many other countries and the rules or guidelines followed in the country needed to be revived to allow such students to pursue co urses where colour blindness might not be a handicap.

“Total exclusion for admission to medical courses without any stipulation in which they really can practise and render assistance would tantamount to regressive thinking. When we conceive of global phenomenon and universal brotherhood, efforts are to be made to be within the said parameters. The march of science, apart from our constitutional warrant and values, commands inclusion and not exclusion,“ the bench said. The court directed Medical Council of India, the apex regula Council of India, the apex regulating body in the field of medical studies and profession, to constitute a committee of experts from genetics, ophthalmology , psychiatry and medical education from AIIMS and PGIMER, Chandigarh, to examine the issue. The court directed that the committee submit its report in three months.

The court passed the order on a plea of two medical students who were denied admission in college after clearing the entrance examination in 2015 as they were suffering from partial colour blindness. They had first approached TripuraHC which had turned down their plea, compelling them to approach the apex court.

Opposing the plea of stu dents, senior advocate Vikas Singh and lawyer Gaurav Sharma, appearing for MCI, contended that the decision to bar colour blind people was taken on the basis of report of an expert committee which held that people with such handicap would not be able to perform their duty as a doctor. They said a doctor would not be able to do fair diagnosis and prognosis of a disease as it depended upon colour detection Senior advocate K V Vishwanathan, who was asked to assist the court in deciding the issue, said a colour blind person may face difficulty in the stream of pathology , surgery, skin and general medicine but could efficiently perform in the field of psychiatry, social and preventive medicine. He said a complete ban on the admission to MBBS course would be violative of constitutional principle of equal opportunity and fair treatment.

’Colour vision deficiency should not be absolute bar:’Committee

A decades-old bar against colour blind people from becoming doctors is set to be removed with a Supreme Court-appointed committee recommending to the court that the current discrimination on the basis of colour vision deficiency (CVD) must be done away with.

Holding that the medical council of India (MCI) rule preventing colour blind people from taking up medical studies is “regressive“, the apex court had set up the committee in March this year, comprising experts from the fields of genetics, ophthalmology , psychiatry and medical education to review the regulation and analyse issues regarding CVD and the norms in other countries.

The committee, whose report has been filed by MCI's counsel Gaurav Sharma, agreed with the apex court's views and has said that CVD should not be an absolute bar as it is a common problem and did not significantly impact a person's ability to practise medicine. The report said there should not be any restriction either at the stage of admission, or at completion of study and registration as a medical practitioner.

“There are many reasons why doctors with CVD may perform as well as those with normal colour vision. Firstly , the diagnostic and treatment process is not solely reliant on the ability to perceive colours. There are many other cues from history of illness and examination that might be utilised to compensate for handicaps resulting from CVD. Doctors with CVD can also overcome their difficulties by carrying out a more thorough diagnostic assessment and taking the help of other colleagues,“ it said.

In its 35-page report, the committee said India is perhaps the only country where colour blind people are denied admission in medical colleges.CVD is not considered as a cri terion for rejection in US, UK and other western countries.

While setting up the committee, a bench headed by Justice Dipak Misra had said, “With the progress of science, expansion of many vistas of knowledge, inclusive culture, having regard to inclusive society and respect for differently-abled persons, it is obligatory on the part of MCI to take a progressive measure so that an individual suffering from colour blindness may not feel like an alien to the concept of equality .“

Severity of CVD might also be factored in while easing the bar for colour blind people as the report noted that “though the risk of medical errors may still exist, particularly among those with more severe CVD, the extent and seriousness of these errors is not clearly evident from the existing research“. “ As per current international practices, there is no policy of regulating entry of medical aspirants to study and practice of the medical profession based on colour vision deficiency . There are also no identified or mentioned practice restrictions,“ the report said.

The committee has noted that there is no identifiable compromise in the abilities of a clinical practitioner with CVD though certain tasks pertaining to specific fields of higher studies and super-specialisation might need closer evaluation. But colour corrective contact lenses or spectacles may be considered to assist the person, if and when necessary .

Commercialisation of medical education

1999-2019

Rema Nagarajan, June 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 9, 2019: The Times of India

How medical education became a business, one policy change at a time

Move to lift fee cap one more step towards commercialisation, say activists

The draft National Education Policy’s call for abandoning all regulation of fees in professional courses marks the latest in a series of steps that have aggressively pushed commercialisation of medical education over the last decade, say public health activists.

Till 2009, the official stance was that education could not be for sale or a for-profit venture. So on paper, all private colleges were run by trusts or charitable societies. Yet, the fact that many made illegal profits through capitation fees, hugely inflated tuition fees and other charges was an open secret. In February 2010, the then UPA government allowed companies registered under the Companies Act to open medical colleges though with the ironical caveat that “permission shall be withdrawn if the colleges resort to commercialisation”.

Even this fig leaf was dropped in August 2016, when then health minister JP Nadda approved an amendment in the eligibility criteria to allow companies to set up for-profit medical colleges. The government argued that no companies were coming forward to set up colleges because of the no-profit stipulation. It also argued that profits were in any case being made in nontransparent ways and that legally permitted profits would at least yield some income tax for the exchequer. There was little or no discussion about how students would be able to afford the huge fees charged in these colleges.

Following a huge outcry over spiralling fees in private medical colleges, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court had directed in 2003 that each state must have an independent fee fixation committee headed by a retired high court judge. A July 2018 Supreme Court judgment again upheld the 2003 judgment.

Mining giant Vedanta was one of the first companies to set up a college, in Palghar, Maharashtra. In a move that shocked the medical fraternity, students and activists, the state government gave it a free hand to decide fees. However, just a couple of months later, the college was found deficient and the Medical Council of India (MCI) refused to allow further intake in July 2018, a decision challenged by the company in Bombay High Court.

Allowing the entry of for-profit companies also led to those running societies or trusts asking why their own colleges could not to be converted into profit-making entities. In January 2017, the government acquiesced and notified that any medical college set up by an autonomous body, society or trust could be converted into a company, thus ending all pretence of medical education being a not-profit venture.

Going a step further, last month, the MCI Board of Governors amended the Establishment of Medical College Regulations, 1999 to allow consortia to set up medical colleges. A consortium, it clarified, could be a group of two to four eligible organisations including a society, trust, company, university or deemed university who have entered into a Memorandum of Understanding. The notification claimed that the object was to invite greater participation from the private sector in establishing medical colleges and “imparting high quality medical education and training facilities… without compromising the standards of medical education”. However, this move is viewed by many health activists as a way for private entities to use public hospitals to start medical colleges through MoUs with a “consortium”. Even before this, in several states including Maharashtra and Gujarat, public facilities had been utilised by private entities to set up medical colleges under the rubric of PPPs (public-private partnerships).

“All this is only about producing more doctors and not about the quality of doctors suited to our needs. Doctor shortage is in rural areas, but with no fee regulation only the affluent will become doctors. Will they serve where the shortage is?” asked Chhaya Pachauli, a public health activist from Rajasthan.

Dr T Sundararaman, former dean of the TISS School of Health System Studies, pointed out that over-production of doctors will suit corporates but not for the country. “Doctors will accumulate in urban areas leading to unhealthy competition and they will try to milk patients as is already happening in Mumbai. We need a policy that will get people to under-served districts of North and North East India,” he said.

While public health activists worry about the implications of a private sector without fee regulation, there is also the question of standards of medical education. India’s experience has been that regulation of private colleges has failed miserably, as both a parliamentary committee and the Supreme Court observed. What reason is there to believe things will get any better, ask the activists.

Capitation fees in govt. colleges

Rema Nagarajan, July 17, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 17, 2019: The Times of India

If you’re a resident Indian with poor NEET scores, getting admission in a government medical college is a pipedream, but if you are an NRI, you have a good shot at it. The reason is that it is not just private colleges commercialising medical education. Some state governments too have joined the bandwagon in the name of making their colleges self-financing. So, 3%- 15% seats are set aside for NRIs and some even have “management quotas”.

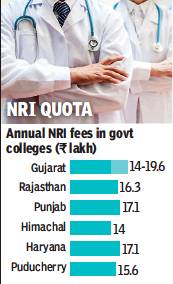

Five states — Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh — and Puducherry have government medical colleges with NRI quotas. Unlike caste-based quotas, which are to compensate for historical deprivation and backwardness, the NRI quota is for being able to charge lakhs as fees. Most states claim the quota is to mobilise funds for maintenance and infrastructure, something that would earlier have come from the health budget.

Gujarat has the highest number of NRI seats at 241, followed by Rajasthan with 212, Punjab with 41, Puducherry with 22, Himachal with 20 and Haryana with 15.

NRI seats are open not only to NRIs but also those they sponsor. Thus, many can use this quota if they have a brother, sister or parent who is an NRI willing to give an undertaking to sponsor the entire course fee. If a student has no parents or is taken as a ward by near relatives, even NRI uncles, aunts or grandparents can be sponsors. There have been several cases of candidates faking eligibility, prompting greater scrutiny of candidates’ NRI claims.

A look at over 1,900 NRI candidates admitted in 2016 shows that almost three-quarters were unreserved category students, barely 3% belonged to SC/STs, and rest were OBCs. While the average NEET score of government quota students including reserved SC, ST and OBC seats in 2016 was 472.5, that of NRI candidates in private colleges was 220.8, and of those in government colleges was 339.6.

The NRI quota fees in government colleges range from Rs 14 lakh to almost Rs 20 lakh per annum. While this is very high compared to the fee charged for the other government seats in most of these colleges (Rs 25,000 to Rs 1 lakh per annum), it is much cheaper than the Rs 30 lakh per annum charged by most private colleges for NRI seats.

Earlier, Andhra Pradesh too had NRI seats in government colleges, but has discontinued this. Madhya Pradesh had about 28 NRI seats in government colleges till 2016 but discontinued the practice in the face of public protests. Last year, the Karnataka government had toyed with the idea of starting an NRI quota in government colleges, but dropped the idea after student outfits threatened agitations.

Former VC of Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences and eminent cardiologist Dr K S Ravindranath explained that the reason for opposing NRI quota in Karnataka government colleges was because it would encroach on seats for poor meritorious students. The government ought to allocate more, but there are never sufficient funds to provide facilities for sports, research, simulation lab etc, he added.

N M Shrivastava, former joint director of medical education in MP, questioned the concept of using NRI seats to generate funds to improve colleges. “The money earned from NRI seats was small compared to the resources required to run a college. Moreover, government colleges are meant for public welfare, for poor to get free treatment and for meritorious students. They aren’t meant to make money. Free education is the government’s job in a democratic welfare state. That’s why the government decided to end NRI quota in MP,” he said.

With inputs from Bharat Yagnik in Ahmedabad, Initshab Ali in Jaipur, Shimona Kanwar in Chandigarh and Pushpa Narayan in Chennai

The societies model

July 17, 2019: The Times of India

The societies model

In Gujarat, ten out of 17 government medical colleges have NRI quota. Eight of these opened since 2011 were by the Gujarat Medical Education and Research Society (GMERS) formed by the state’s health ministry.

GMERS colleges’ quotas mirror those of private colleges with a government quota, a management quota and an NRI quota with annual fees of Rs 14 lakh.

NHL Municipal Medical College in Ahmedabad was set up in 1963 as an entirely municipality-funded college, but became self-financing in 2008-09. Surat Municipal Institute of Medical Education and Research, started in 1999, is also self-financing. Both charge NRI students close to Rs 20 lakh per annum. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation Medical Education Trust Medical College opened in 2009 too has an NRI quota.

In Rajasthan, 11 of the 15 government medical colleges have NRI quota. Like in Gujarat, the Rajasthan health ministry has formed the Rajasthan Medical Education Society under which eight new colleges opened since 2014 are self-financing. Apart from these, the government introduced 30 more NRI seats in three older colleges from this year — 15% of seats increased since 2014-15. The fees for NRI seats in the government colleges ranges from Rs 12.4 lakh in two colleges to Rs 16.3 lakh in the other nine.

Curriculum

2018: adultery, lesbianism are sexual offences

Rema Nagarajan, Adultery, lesbianism now sexual offences, November 14, 2018: The Times of India

The MBBS curriculum being revised after 20 years lists adultery and lesbianism as sexual offences in the section on forensic science, and in the one on obstetrics and gynaecology. Again, in the psychiatry section it puts transvestism in the list of “sexual perversions” and makes a reference to the Indian Mental Health Act, 1987.

Emergency medicine

Residency programmes as masters courses

Hospitals Get Cheap Labour, Medical Societies Moolah

Residency programmes in emergency medicine passing themselves off as masters courses have become a multi-crore industry .Many private hospitals running such courses charge Rs 11-19 lakh for a three-year course. Given the huge demand for doctors trained in the discipline, the industry finds no lack of takers.

Ironically , this ensures that the stipend or salary to be paid to these young doctors over these three years comes out of the course fees they pay. Sources in the private healthcare sector told TOI that this cheap or even free labour to run emergency departments is one of the biggest factors behind the increasing number of private hospitals offering these courses.

The masters in emergency medicine (MEM), administered by the George Washington University (GWU) in conjunction with several private hospitals is termed “a three-year postgraduate program in emergency medicine“ on the GWU website. The MEM being run by the Society for Emergency Medicine in India (SEMI), is promoted as a PG programme by most hospitals on their website, with only the fine print acknowledging it is not MCI recognised.

In the case of GWU-MEM, the affiliation is usually with the “academy“ that most corporate hospitals have, to train medical personnel needed for their hospital chain. Each GWU-affiliated academy or stand-alone hospital pays $60,000 to $90,000 (Rs 39 lakh to over Rs 58 lakh) per year to GWU for course administration and to cover the cost of the GWU faculty's monthly class visits. Each student pays Rs 4-6 lakh per year as fees and get paid about Rs 25,000 per month in the first year, going up to Rs 45,000 in the third year. In effect, the students get their stipend from the fees they pay and the hospital gets the free service of a bunch of doctors for three years.

GWU-MEM started in 2007 as a two-year fellowship.In 2010, a year after MCI recognised emergency medicine as a specialty and started the three-year MD course, the fellowship was converted into a three-year “masters“ programme. SEMI, whose board is dominated by doctors without an MCI-recognised PG medical degree, started its own MEM in 2011 in the name of Make in India.

SEMI took Rs 20,000 per year per student for course administration, much cheaper than the GWU-MEM. Stu dents also pay Rs 3,000 for SEMI life membership and about Rs 17,000 as examination fees. Thus SEMI's revenue from each MEM student is about Rs 80,000. With about 350 MEMs produced each year, that's about Rs 2.8 crore annually. The hospital running SEMI-MEM charges from Rs 75,000 to over a lakh per year as fees, again much cheaper than the GWU-MEM. SEMIMEM students are paid the same stipend as Diplomate of National Board (DNB) students (Rs 25,000 to Rs 50,000 depending on the state), claimed former SEMI president Dr T Srinath Kumar.

SEMI-MEMs have mushroomed across India as it is cheaper for hospitals and gives the same benefits in terms of getting a steady flow of cheap labour to run emergency departments.

SEMI earlier ran a one-year diploma course in emergency medicine, which has been wound up. GWU also used to run a one-year PG diploma. “If the idea was to address the shortage of doctors trained in emergency medicine quickly and to meet the rising demand, why would they extend the training to a threeyear masters programme?

Why not start more one-year diplomas or stick to two-year fellowships?“ asked a senior faculty of emergency medicine in a medical college.

With a huge mismatch in the number of MBBS graduates and recognised postgraduate seats, doctors who cannot make it through the entrance exam for MD and DNB in emergency medicine opt for these training courses even if they are unrecognised, as they help them get jobs in private hospitals. Societies like SEMI are glad to keep these lucrative courses running. Since emergency training courses include rotation to other departments including ICUs, hospitals are keen to get EM trainees they can use across departments. Some hospitals with just 60 emergency patients per day were training 14 one-year diploma students in emergency medicine along with 12 MEM trainees, raising questions about the quality of training. No one is opposed to training programmes as long as students are not cheated into believing their courses will get them a PG qualification that can be registered, and as long as the organisations running these courses do not claim their courses are equivalent to a recognised PG degree, pointed out Dr Praveen Aggarwal head of the department of emergency medicine at AIIMS.

Training courses in various specialties run by medical societies are common, but those do not claim to be a masters programme or degree.They are typically called certificate courses, fellowships or diplomas.

Ethics

2018: included in curriculum

Rema Nagarajan, Now, MBBS students to do course on ethics too, November 14, 2018: The Times of India

India has joined a long list of countries that have included a course in medical ethics as part of undergraduate medical education. The course will start from the first year of the MBBS programme and run until the final year.

The Competency Based Medical Curriculum uploaded on the Medical Council of India (MCI) website underscored the importance of ethical values, responsiveness to the needs of the patient and acquisition of communication skills through dedicated curriculum time for acquiring what it called “Attitude Ethics and Communication (AETCOM) competencies”. In the foreword to the curriculum, the Board of Governors currently running the MCI stated that medical students should be “trained to effectively communicate with patients and their relatives in a manner respectful of the patient's preferences, values, beliefs, confidentiality and privacy”.

Over the past four years, a panel of experts laid the basic framework for the revised MBBS curriculum. A book on AETCOM was prepared by the MCI and training of faculty on this module has been on since 2015. The curriculum set out the expectation from introducing the module stating that along with medical skills a medical graduate ought to be able to appreciate the sociopsychological, cultural, economic and environmental factors affecting health and develop a humane attitude towards patients.

According to the chairperson of the MCI Board of Governors Dr Vinod K Paul, emphasis on attitudes, ethics and communication was missing earlier as students mostly learned these from their peers, seniors and teachers. “By the 1990s, it had become obvious that ethics was important and most countries had introduced it in the medical curriculum. The framework of ethical decision-making is my shield to society when questioned about the decisions I take and doctors need to be taught how to wade through increasingly complex situations. Teaching AETCOM is a formal attempt to bring out the best in students. It will not change everyone, as students come with their own socializing and from different backgrounds. But the majority will benefit from it,” said Dr Paul.

Welcoming the introduction of medical ethics in the curriculum, eminent gastrointestinal surgeon Dr Samiran Nundy said the challenge would be to ensure that it was not restricted to didactic teaching and that it was relevant to India. “The most important thing is for the professors teaching ethics to practise what they preach. Students learn by emulating their teachers and so teachers must be seen doing what is right,” said Dr Nundy.

Dr Arun Gadre of the Alliance of Doctors for Ethical Healthcare, said the introduction of any ethics anywhere is good but felt that without role models in colleges, just teaching the theory of ethics would only make students cynical.

Foreign educated Indian doctors (FEIDs)

2012-14: Indian doctors with foreign medical degrees

The Times of India, Nov 06 2015

Sushmi Dey

China beats all to be biggest doctor factory for Indians

Not just Chinese consumer products, India also receives thousands of “made in China“ doctors. China is today the largest contributor of MBBS doctors to India followed by Russia, Ukraine and Nepal, according to data collated by the National Board of Examinations, which conducts Foreign Medical Graduate Examination (FMGE) screening tests. The FMGE is a voluntary entrance test introduced in 2002 as a qualifying exam for Indian students holding medical degrees from other countries and intending to practice medicine in India. The Medical Council of India (MCI) recognises this exam.

As many as 11,825 Indian students, who have Chinese MBBS degrees, took the FMGE test during 2012-2014, while 5,950 were from schools in Russia and 3,163 in Nepal. The rush for foreign destinations, experts say , is fuelled by those who fail to get admissions in Indian colleges. Of over 5 lakh Indian MBBS aspirants each year, about 4,500 get seats in government colleges.

While UK, Germany and Singapore attract candidates, the numbers are comparatively smaller than those who go to China and Nepal for European institutes are costlier. The number of doctors who train in countries like China and Russia has risen sharply in recent years, but they must clear the Foreign Medical Graduate Examination (FMGE) for provisional or permanent registration with Medical Council of India or any state medical council. There's an impression, however, that the calibre of doctors who train in these countries isn't on a par with those qualifying from Indian institutions.

The National Board of Examinations that conducts the FMGE ranks foreign universities or medical institutes on their candidates' performance in the screening test. While the government plans to increase PG seats in some super-specialty departments in a few key institutes, including AIIMS, there are no such plans for basic MBBS course.

Country of education, pass percentage

From: DurgeshNandan Jha, MBBS grads from abroad face a hard road to licence, October 1, 2018: The Times of India

Degree No Use Till They Clear Screening Test

It is unusual for medical graduates in India to be embarrassed around their relatives. But Kumar Gaurav, who completed his MBBS in March 2016, has not visited his Bihar hometown in two years. His relatives had once made fun of him because he couldn’t practice despite having a medical degree. And that had stabbed him right in his heart.

Gaurav went to a medical college in Nepal, but graduates from there can’t practice in India unless they clear the Foreign Medical Graduates Examination, a screening test conducted by the Medical Council of India twice a year. This applies to graduates from institutions in other countries as well, such as China, Ukraine, Russia, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

Fresh graduates return to India and join the ranks of those who have been trying to pass the test. It’s a tough life.

Chhattarpal Vasisth, who did his MBBS from Ukraine, is now enrolled in a coaching institute in South Delhi to crack the screening test. The 26-year-old comes from a small village in Haryana’s Bhiwani, and the first to be a doctor from there. “I could not get admission in government medical colleges. Private colleges charged over Rs 50 lakh. In Ukraine, it cost me less than Rs 20 lakh, including hostel fees,” he says.

Like Gaurav and Vasisth, more than 5,000 young men and women opt for medical degrees abroad every year because of low cost and ease of admission, among other reasons. China is the most popular destination, followed by Russia, Ukraine, Nepal, Kazakhstan and Bangladesh. Some even go to Pakistan.

The life that follows their return to India is different from what most anticipate. They also have to deal with the realisation that, hierarchically, they are considered less meritorious than homegrown medical graduates.

Gautam Nagar near AIIMS in Delhi is known for the large number of medical graduates and aspiring students who live there. Behind AIIMS are the lanes of Gurjar Dairy, an unauthorised colony where hundreds of medical graduates from abroad live in dingy accommodations, while enrolled in coaching classes and dreaming of cracking FMGE. “When I went to study in Ukraine, I assumed I would be more sought-after here on my return. Life was tough there. I lived on a tight budget and worked at restaurants,” says Dr Saurav Awasthi, an MBBS now employed at a government hospital in Delhi.

Med grads from abroad perform poorly in FMGE

People think we did not have the merit to study medicine but partied and came back with easy degrees. This is not true. Education standards there are better than most private medical colleges in India and even some government ones,” says Dr Saurav Awasthi, an MBBS, now employed at a government hospital in Delhi. He is a leading member of All India Foreign Medical Graduates Association, which works for the rights of students like him.

Their image is not enhanced by the fact that graduates from abroad perform poorly in FMGE. Between 2012 and 2014, graduates from Bangladesh performed the best, with 31% clearing the test. Then there are countries like Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, from where only 18% graduates make the cut. Each year, more than 10,000 appear for FMGE. In the June 2014 exam, only 5% passed. In June this year, the figure was slightly more encouraging: 26%.

Awasthi and others say the government should make the test compulsory for all graduates, including those from Indian colleges. Dr Yatish Aggarwal, an advisor to the National Board of Examination that conducts FMGE, points out, “A few years ago, following protests by foreign graduates over low pass percentage in FMGE, we asked some finalyear students from Maulana Azad Medical College and Vardhman Mahavir Medical College to take the test without prior notice. Nearly 80% of them qualified. Less than 20% of the foreign graduates made it.”

Recently, the health ministry issued directions that any Indian candidate wishing to pursue medical education from any foreign destination will have to pass the National Eligibilitycum-Entrance Test from now on.

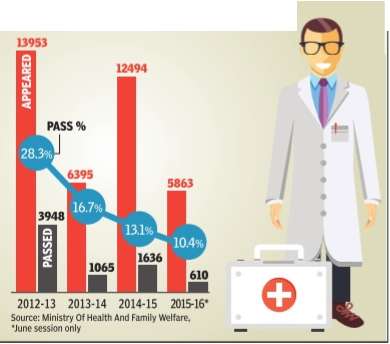

2012-16: Poor ‘pass percentage’

The Times of India Jan 04 2016

The pass % of foreign medical degree holders in the screening test for recognition of their degrees in India is steadily declining. Student bodies complain about deliberately set tough questions to discriminate them against students from Indian universities.The examination bodies say that pass % is going down because of the increasing number of repeaters

2014-16: Poor performance in screening tests in India

The Times of India, May 25 2016

Pushpa Narayan

Statistics show students with medical degrees from foreign countries are finding it increasingly difficult to pass the screening test that allows them to practice in India.

The number of students taking the test has doubled but the pass percentage dropped from 50.12 in 2005 to 10.7 in 2015. In this period, the pass rate fluctuated around 20%, dropping to an all-time low of 4.93% in June 2014, when only 293 students passed. There has been an 80% drop, between 2005 and 2015, in Indian medical graduates from foreign universities passing the mandatory screening test that the National Board of Examinations holds.

According to the Indian Medical Council Act, 2001, citizens with undergraduate degrees from outside India should clear the screening test conducted twice every yearJune and Decemberbefore they do a one-year in ternship in one of the MCIrecognised medical colleges.One has to score 50% to clear the test. Students say the the test is extremely tough.“Most questions are from postgraduate medical tests,“ said Raghuram Nayak, who completed his graduation in Ukraine in 2012. The students' association of foreign medical graduates say the board has made the test difficult to discourage students from going abroad and opt to study in private colleges here that charge as much as Rs 1 crore.

These students aren't even considered graduates in India unless they pass the test. “ Many of students spend lakhs in coaching centres to clear the test,“ said Raghuram. Officials at NBE deny these.

An expert committee which studied 11 question papers from 2013 to 2015 submitted a report to the ministry of health stating that 52.78% of the questions were of “low difficulty“ and 42.22% questions were of “moderate difficulty“. Board executive director Dr Bipin Batra said the test had no negative marking and most students find it difficult because public health priorities of other nations are different from ours.

2016-17: 74% rise in Indians seeking foreign degrees

Sushmi Dey, December 18, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sushmi Dey, December 18, 2018: The Times of India

Number of students aspiring to study medicine abroad is rising rapidly with applications from such candidates increasing by 74% in just one year between 2016-17 and 2017-18, official data show.

The Medical Council of India (MCI) received 18,383 applications in 2017-18 for the mandatory eligibility certificate required so far from the medical education regulator to study medicine abroad, as against 10,555 applications in the previous year, as per information given by MCI in response to an RTI application.

MCI issued a total of 14,118 eligibility certificates in 2017-18, compared to 8,737 in 2016- 2017.

Experts say while the number of medical seats are limited in India, increasing awareness about foreign institutes coupled with their affordability has resulted in more aspirants seeking admissions abroad.

“Information provided in the RTI speaks volume on the shift in medical education trends. The key reason for this is the lack of medical seats in India. Apart from this, higher awareness levels of the overseas colleges, more affordable fees compared to Indian private colleges, curriculum aligned to international standardsetc. are other reasons why students prefer to study MBBS abroad,” says Saju Bhaskar, president & founder of an overseas medical university, Texila American University.

However, there are concerns in the Indian medical fraternity that the trend will impact the quality of doctors coming to practice in India. “Quality of medical education in India is one of the best in the world. However, since the number of seats are limited and candidates have to qualify a tough test, other countries like Russia, China and Eastern Europe provide an easy path, mainly for those who can pay,” says Dr Gurinder Grewal, former president, Punjab Medical Council.

Around 12 lakh aspirants take NEET for undergraduate medical course every year. Out of this, around six lakh clear the exam for about 68,000 MBBS seats. The rest try for dental and Ayush (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy) courses. Many of these candidates, who fail to qualify NEET, also pursue medical education abroad, mainly in countries where they can seek admission with entrance examination.

Medical colleges

2017: states where concentrated; private/ government

March 31, 2018: The Times of India

The number of private Medical colleges vis-à-vis government Medical colleges.

All figures presumably relate to 2017

From: March 31, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The 7 states where Medical colleges are concentrated;

The number of private Medical colleges vis-à-vis government Medical colleges.

All figures presumably relate to 2017

2018: the best and worst served states

Rema Nagarajan, June 18, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 18, 2019: The Times of India

Jharkhand last got a ‘new’ medical college 50 years back

Can you believe that there is a state that hasn’t had a single new medical college opening in half a century? The last medical college to open in Jharkhand was the government-run Patliputra Medical College in Dhanbad in 1969, long before the state even came into existence. There are just two more medical colleges in the state, both government-run, opened in 1960 and 1961. Jharkhand also happens to be the state with the worst doctor to population ratio of close to one for every 8,200 people.

In spite of this, even in 2019, the year that witnessed the largest ever expansion of medical seats, especially government seats, Jharkhand did not get a single new college. About 231 medical colleges have been opened across India since 2010, yet not one in Jharkhand. An AIIMS has been sanctioned for Deoghar in the state, but that’s still in the pipeline.

Chattisgarh is another state with an abysmal doctor-population ratio of 1:4,338. Yet, it too got no new colleges in the 2019 mega expansion. Bihar, with a doctor-population ratio worse than 1:3,200 got just one new private college. Thus the three states worst off in terms of doctorpopulation ratios have been largely ignored even in the current year. Unlike Jharkhand, however, Chhattisgarh has added seven new colleges since 2010, four of which were government run, though two of these seven have been debarred from admission this year. Bihar too has added six new colleges from 2010, including four government ones with 100 seats each.

Other states with poor doctorpopulation ratios such as Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh got seven, four and three government colleges respectively, each with 100 seats in the 2019 expansion. Even states which already have a glut of doctors, like Tamil Nadu with one doctor for just over 250 people, got two new colleges, one private and one government owned, with 150 seats each. From 2010 onwards, medical colleges and MBBS seats have increased substantially, especially in the government sector. Every big state, including those complaining of over-production of doctors has continued to open new medical colleges barring Jharkhand. Uttar Pradesh saw the greatest increase with the addition of 29 colleges taking the total number to 55, second only to Karnataka with 59 colleges. The state has only one doctor for every 3,767 persons. Interestingly, Karnataka, which already had among the highest number of medical colleges, saw 19 more being opened from 2010, of which 10 were private with 150 seats each. Of these 10 new private colleges, five have been opened in Bengaluru, which already had seven. Two of the nine government colleges set up since 2010 are also in Bengaluru, taking the total in the city to 14. Karnataka’s doctor-population is 1:507, well above the WHO target of 1:1,000.

Tamil Nadu has added 13 colleges since 2010, of which seven were government colleges. It now has a total of 49 colleges, not counting nine in adjoining Pondicherry. Kerala, which is also facing a glut with one doctor for about 500 people, added four government colleges with 100 seats each and seven private one with 150 seats each in the current decade. The net result is that some states are facing a steadily worsening glut of doctors while others are facing desperate shortages that are not getting addressed.

2018-19: government vis-à-vis private colleges

From: March 12, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

Management-wise colleges and enrolment, 2018-19

Neglect of medical education

1 govt med college seat for 55k people

Massive Shortage Of Seats Allows Private Sector To Jack Up Education Cost

Rema Nagarajan | TIG

The Times of India 2013/08/12

Shortage of doctors

The shortage of doctors in India can be blamed on the government neglecting medical education for three decades from 1970 till 2000. In a 15-year period from 1951 to 1966, sustained investment in medical education led to India having one medical seat in a government college for roughly every 37,000 persons, down from one for every 71,000 in 1951.

Over the 47 years since then, the situation has worsened dramatically with one government medical college seat for over 55,000 today. This has resulted in the private sector taking over medical education in a big way. That, in turn, has meant spiralling costs, question marks over quality and a sharp geographical skew. Even with the private sector included, India now has one MBBS seat for every 26,042 people, only a small improvement from one for every 33,521 in 1966. In contrast, the period from 1951 to 1966 had seen the ratio cut by more than half.

A look at the data on medical seats and colleges available with the Medical Council of India (MCI), the regulator for medical education and doctors, shows that the availability of medical seats has improved in recent years. Almost half (47%) of the available seats have been created since 2000. However, 72% of the seats added since 1970 are in the private sector.

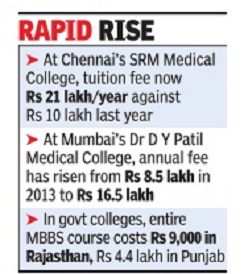

Why should this be a matter of concern? There are several good reasons for this to be cause for worry. For starters, private medical education is expensive making it inaccessible for most Indians. In private colleges, the cost of graduating is Rs 15 lakh-40 lakh or more, not including capitation fees. In a government college, it ranges from a mere Rs 10,000 as tuition fee in Delhi’s Maulana Azad Medical College for the entire MBBS course to about Rs 1.5 lakh in Trivandrum Medical College, one of the more expensive government medical colleges.

The quality of education in private medical colleges, too, has been a matter of great concern as they are less transparent and have proved difficult to regulate. The fact that many are owned by political heavyweights does not help.

The lost states, the lost decades

The private sector has also led to a geographical skew in the distribution of seats. Over half the private sector seats are concentrated in just four states—Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra and Kerala—though they account for just 21% of India’s population. In Karnataka, for every government seat, there are almost four private medical seats, while in Kerala there are two private seats for every government seat. However, in the poorer states like Bihar, UP, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Assam, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and in the northeast, medical education remains largely dependent on government medical colleges. In most of these states, no new government medical colleges were created for decades between 1960s and 2000. In over two decades following Independence, the government created 69 medical colleges with over 8,500 seats. This was followed by three decades (1970-99) of utter neglect, when the population almost doubled from 548 million to over a billion, while the government added barely 2,000 more medical seats. The surge of the private sector started in the 80s as government investment in medical education declined drastically, but it has accelerated since the turn of the century.

After the government woke up to the crisis in medical education and took steps to increase government investment and also relaxed the norms for running a medical college, there has been a surge in the number of medical colleges, both public and private, especially in the last three years.

Aformer member of the Board of Governors of the MCI, Dr Ranjit Roychoudhury, had this to say: “We lost three decades starting from the 70s. The government stepped back from medical education thinking that the private sector would be able to fill in. At the time, the problems of private medical education were not envisaged, such as the question of inequity, quality of education and the geographical skew. We are now trying to rectify this problem.”

2000-2013

Since 2000, the government has created 9,300 medical seats, almost as many as it did in half a century from 1950 till 2000. But the 9,300 seems a pittance compared to the 17,700-plus private sector seats created in the same period. Almost 60% of the latter were in four southern states. In 2013, for the first time since 1975, the government has created more medical seats than in the private sector. In 2013, Centre created 1,300 seats in 14 new colleges. Another 3,013 have been added to existing colleges. Thus, in just this year, the government has created twice as many seats as it did in 30 years from 1970 to 2000. Is the trend finally changing for the better? Let’s hope so.

Nursing colleges

INC cannot recognise nursing colleges: HC

INC not authorised to recognise nursing colleges: High Court, July 25, 2017: The Hindu

Council told not to webhost material indicating institutions require its recognition

The High Court of Karnataka on Monday declared that the Indian Nursing Council (INC) has no authority to grant recognition to institutions imparting nursing courses. It restrained the INC from publishing on its website material indicating that the institutions have to obtain recognition from it.

The court held that the council is empowered to prescribe qualification and syllabus for nursing courses, and not to accord recognition to colleges.

Justice L. Narayana Swamy delivered the verdict while allowing petitions filed by the Karnataka State Association of the Managements of Nursing and Allied Health Sciences Institutions, and some nursing colleges.

Also, the court said that all such stands withdrawn from the INC’s website forthwith.

The action of the INC claiming that nursing colleges have to get recognition from it, publishing the list of recognised colleges, and releasing any such material on its website, would cause hardship to petitioners and nursing colleges as students, who visit the website would infer that colleges which are not in the list, are not recognised.

‘Against the law’

The action of the INC in publishing the list of recognised nursing institutions is against the law declared by the High Court in a earlier case of 2005 as well as an order of the Supreme Court, Justice Narayana Swamy observed in the order.

The petitioner-association had claimed that the INC has no authority to grant recognition to institutions imparting nursing courses, such as auxiliary nurse and midwife, general nursing, B.Sc. Nursing and M.Sc. Nursing, after the INC removed Karnataka’s nursing colleges from the list of recognised institutions of nursing.

The association had supported the State government’s notification of December 14, 2016, which was issued citing 2005 order of the High Court, clarifying that the power to grant recognition, impart training in nursing and fixation of intake vests with the State government, the Karnataka State Nursing Council and the Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences and not the INC.

Prior to the December 2016 notification, the State had insisted recognition from the INC.

Petitions rejected

Meanwhile, the court rejected the petitions filed by Student Nurses’ Association of the Trained Nurses’ Association of India and several other nursing colleges seeking a direction to the INC to renew or grant recognition to the nursing institution, while claiming that it is the INC that has to grant recognition to their qualification if their nursing certificate or degree is required to have recognition across India and abroad.

PG Medical courses

Admissions only on merit: SC

The Times of India, Jan 13 2015

Admissions to PG medical courses only on merit: SC

Admissions to post-graduate medical courses can be done only on the basis of merit of students appearing in the entrance examination, the Supreme Court said while quashing Kerala government's decision to reserve seats for doctors working in its hospitals and other departments. The apex court said the state overstepped its jurisdiction by making a law earmarking 40% of total seats available to the state quota for its medical officers who were to get admission on the basis of their seniority , without appearing in the entrance examination.

A bench of Justices T S Thakur and R Banumathi said regulations framed by the Medical Council of India were binding and state governments could not make any rule in violation of the regulations. “Regulation 9 (of MCI) is, in our opinion, a complete code by itself inasmuch as it prescribes the basis for determining the eligibility of the candidates including the method to be adopted for determining the inter se merit which remains the only basis for such admissions. To the performance in the entrance test can be added weightage on account of rural service rendered by the candidates in the manner and to the extent indicated,“ it said.

The court said the method, however, was given a go-by by the impugned legislation when it provided that in-service candidates seeking admission in the quota shall be granted such admission not on the basis of one of the methodologies but on the basis of seniority of such candidates.

Change in rules for those with disability/ 2018

PG med admission: Change in rules for those with disability, March 22, 2018: The Times of India

The health ministry has granted approval to amend the rules for admission of people with disabilities in postgraduate medical courses to help them get the benefits of reservation, according to an official statement.

The percentage of seats to be filled by people with disabilities has been increased from 3% to 5% in accordance with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, the statement said. Union health minister JP Nadda termed it a “historic” decision. “Now all with 21 benchmark disabilities as per the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, can register for admission to medical courses,” he said. According to the amended provisions, the disabilities include hearing impairment, locomotor disability, dwarfism, intellectual disability, autism, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis and thalassemia.

50% institutional preference for PG medical seats

Banaras Hindu University (BHU) and Aligarh Muslim Univesrity (AMU) will stand together on the same side in the Supreme Court to challenge an Allahabad High Court order doing away with 50% institutional preference in admission to PG medical seats.

BHU and AMU, both central universities, are relying on the Supreme Court's 2003 judgement in the Saurabh Chaudri case laying down the guidelines for filling up of PG medical college seats in government colleges. The SC had held that 50% of the seats would be reserved for all-India quota to be filled through a common entrance test. The government medical colleges could give preference to candidates from their own institution to fill the balance 50% seats in post-graduation courses.

On a PIL, without making the BHU or AMU a party, the HC had opened the 50% institutional quota seats in PG medical courses in these two central universities for students from any medical college in UP based on their ranking in National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET).

“The implication of the HC order is that the admissions to the MD, MS and MDS courses in BHU as well as AMU, which has already been finalised and completed for the year 2017, has been rendered void. The HC did not offer any opportunity to the petitioner university to establish justify the validity of 50% quota available to the university under the institutional category,“ the BHU said and sought an interim stay of the HC order.

PG courses: weightage for rural service

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court said on Wednesday that a doctor who forgoes urban comforts to serve in rural areas could not be denied the consequent weightage for admission to PG courses in government medical colleges of any state just because he obtained the MBBS degree from another state.

A bench of Justices Ashok Bhushan and Deepak Gupta set aside an order of the Allahabad high court, that granted preference in admission for PG courses to those in-service doctors who rendered rural service in UP after graduating from a medical college of the state.

The bench said: "Once graduate doctors, whether they cleared their MBBS or BDS examination from within UP or from any other part of the country, are selected and join the medical health service in UP, they form part of one service - Provincial Medical Health Services. Thereafter, when these doctors are posted to remote or difficult areas, they are posted as doctors of PMHS and not on basis of the state from where they did their graduation."

With this ruling, an MBBS passout from any state can join rural health services in another state and still be able to avail of the weightage, an additional 10% of marks per year of rural service up to a maximum of 30%, for admission to PG courses in the state where he rendered rural services.

The SC also set aside another direction of the Allahabad HC which had annulled the institutional quota of up to 50% of seats in PG medical courses of Aligarh Muslim University and Banaras Hindu University and directed filling up of these seats from among candidates who have passed MBBS from institutions, universities and colleges in UP.

SC sets aside HC order on institutional preference

Jun 7, 2017: The Times of India

SC sets aside Allahabad HC order on PG medical seats

NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court set aside the Allahabad High Court's May 29 order which had quashed 50 per cent institutional preference in admission to PG medical seats.

A vacation bench comprising Justices Ashok Bhushan and Deepak Gupta said institutes like the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) and the government-run medical colleges in UP will continue conducting counselling and fill up the seats by June 12.

The high court on May 29 had passed order allowing to fill up the 50 per cent institutional quota seats in PG medical courses in these two central universities and other government-run univerities for students from any medical college based on their ranking in NEET.

The apex court order came on the plea of BHU and AMU contending that the high court verdict was violative of earlier apex court judgement and Medical Council of India (MCI) regulations which allow institutes to take admissions on 50 per cent seats from their own institution.

Both these central universities had got the support from the MCI, which had argued that the high court has erred in interpreting the laid down regulations. Additional Solicitor General Maninder Singh, appearing for BHU, had sought immediate stay of the high court's order saying the "entire apple cart" cannot be reversed. Senior advocate Salman Khurshid, appearing for the AMU, had said some students have already been admitted by the varsities under the 50 per cent quota, therefore the high court verdict needs to be stayed.

SC finds serious flaws in HC’s order

AmitAnand Choudhary, Med admissions: SC rips into HC’s order, November 26, 2017: The Times of India

The permission given by a division bench of the Allahabad high court to a Lucknow-based medical college to admit students just three days after the Supreme Court rejected the plea has elicited a strong reaction from the apex court, which called it a case of “judicial indiscipline” as it minced no words to reprimand the judges for violating judicial propriety.

A bench of CJI Dipak Misra and Justices A M Khanwilkar and D Y Chandrachud expressed “shock” and slammed the judges for passing an order “for some unfathomable and inscrutable reason”, a deviation which has the “potentiality to take justice to her coffin”.

‘HC move shows unjustified haste’

It is a most unfortunate situation that the division bench has paved such a path. One cannot but say that the adjudication by the division bench tantamounts to a state as if they dragged themselves to the realm of ‘willing suspension of disbelief’. Possibly, they assumed that they could do what they intended to do,” the SC bench said.

“A judge cannot think in terms of ‘what pleases the prince has the force of law’. Frankly speaking, the law does not allow so, for law has to be observed by requisite respect for law,” it said.

The bench noted that the Supreme Court had, on August 28, restrained the high court from passing any interim order in favour of the medical college for the current academic year while allowing the institution to withdraw its petition.

The high court, however, allowed the college to admit students for the 2017-18 batch on September 1withoutwaiting for a response from the Centre and the Medical Council of India.

“It is clear as the cloudless sky that the judgment of the high court shows unnecessary and uncalled-for hurry, unjustified haste and an unreasonable sense of promptitude possibly being oblivious of the fact that the stand of the Medical Council of India and the central government could not be given indecent burial when they were parties on record. Such a procedure cannot be countenanced in law,” the apex court said.

“The content of the August 28 order is graphically clear. The HC was not allowed to pass any interim order pertaining to the academic session 2017-18 but the division bench of HC, for some unfathomable and inscrutable reason, referred to certain judgments of this court and allowed the prayer. It is beyond our comprehension as to how the high court could have even remotely thought of passing an order granting the letter of permission for the academic session 2016-17 and renewal for 2017-18,” it said.

The apex court said: “It is necessary to add and repeat that the division bench had no reason to abandon the concept of judicial propriety and transgress the rules and further proceed on a path where it was not required to. Such things create institutional problems and we are sure that the judges shall be guided by it.”

The bench noted that the SC had restrained the HC from passing any interim order in favour of the medical college in Lucknow

One cannot but say that the adjudication... tantamounts to a state as if they dragged themselves to the realm of ‘willing suspension of disbelief’. Possibly, they assumed that they could do what they intended to do. It has the potentiality to take justice to her coffin

— SC BENCH on HC judges

Many hospitals with PG seats don’t meet standards/ 2017-19

Rema Nagarajan, May 11, 2019: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, May 11, 2019: The Times of India

Fake faculty, fake patients, inadequate infrastructure — these grievances are common about private medical colleges. They are now cropping up in complaints against private hospitals accredited by the National Board of Examination (NBE) for post-graduate seats. Yet, when a student complained about one such institution, the board responded saying that the hospital authorities “confirmed that they are following all the norms, rules and regulations set by NBE” and hence the matter was being closed. There was no investigation or inspection to check whether the complaint had merit. The assurance of the accused was enough for the matter to be closed. This despite the fact that there have been several cases of hospitals shutting shop or DNB (Diplomate of National Board) programmes having to be shut down for not complying with the minimum requirements to run the programme. In most cases, NBE had to relocate the stranded students to other hospitals. In 2018 alone, DNB programmes in 12 institutions accounting for 44 seats in various disciplines had to be shut down and 50 students had to be relocated. In 2017, three DNB programmes accounting for seven seats had to be discontinued. Mercifully, no students had to be relocated as there were none.

No programmes were shut down in 2015 and 2016. “Since there was no governing body in 2015 and half of year 2016, no decisions were made regarding withdrawal of accreditation,” said an NBE spokesperson. With no governing body, students’ complaints went unresolved forcing many of them to drop out of DNB programmes. NBE regulates DNB, a post graduate qualification like MD/MS. DNB seats are mostly in private hospitals or institutions accredited by the NBE after an assessment to ensure that they have the required infrastructure, patient load and faculty. Single specialty hospitals must have at least 100 beds and multi-specialty hospitals at least 200 to be eligible for a DNB seat. However, DNB students in several hospitals have complained about not even 100 beds actually being available and asked the NBE to do surprise inspections.

“Unlike MCI, which puts up assessment reports of medical colleges in the public domain, the NBE refuses to do so. Hence students have no way of knowing what kind of an institution they are joining or what infrastructure the institute claims to have. Shifting students to other cities in the middle of a course causes much hardship,” said Dr Teena Gupta, National Secretary of the Association of DNB Doctors.

2018: MRCP, 4 other countries’ PG equal to Indian PG

Royal College Membership Only An In-Training Exam, Not A Qualification

Membership of the Royal College of Physicians of the UK (MRCP-UK) is only an “intraining examination” and not a qualification for recognition as a consultant in the UK. However, it is being considered as equivalent to an MD, MS or DM in India — all postgraduate degrees that qualify a person for consultant status — after the Medical Council of India issued a notification in March 2017 that postgraduate qualifications awarded in five countries including the UK would be treated as equivalent to these Indian degrees.

Since then, several private hospitals have started offering MRCP stating that it is equivalent to postgraduate medical degrees in India. However, responding to TOI’s queries, Professor David Galloway, president of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow clarified that MRCP is an “intraining examination” that is “set well below the level required at completion of specialist training”. The MCI is currently re-examining the issue of equivalence of MRCP and a final decision in the matter is awaited.

In India, the MRCP is promoted as a three-year structured post-graduate programme with core medical training (CMT) being offered in partnership with the Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. According to the MRCP-UK international brochure, the three-part MRCP(UK) merely makes a person eligible for higher specialist training.

In India, only an MBBS doctor with post graduate degrees like MD or MS can become a specialist or consultant. In the UK, as Galloway pointed out, “a CCT is required to gain a UK consultant position”. Certificate of completion of training (CCT), which takes five years, shows that a doctor has completed an approved specialist training programme and is eligible to become a consultant in the National Health Service in the UK. He added that the CCT is a very different standard and should not be compared to the MRCP.

Dr Galloway also clarified that the CMT being offered as part of MRCP courses in India was not the same as CCT. CMT refers to core medical training, that is early years post graduate training, and it is just part of the full general internal medicine curriculum of five years, he said.

Thus, a qualification that is not even considered a postgraduate degree in its home country is being considered so in India and equivalent to MD/MS for appointment to the post of assistant professor in medical colleges.

In the case of MBBS degrees given by foreign universities or institutions, the MCI stipulates that it has to be a recognised qualification for enrolment as medical practitioner in the country in which the institution awarding the qualification is situated. Only if this is true does the MCI grant the eligibility certificate that is required for taking the screening test that foreign medical graduates must clear to be allowed to practice in India. Yet, this principle does not seem to have been applied to the MRCP-UK with CMT.

In India, only an MBBS doctor with PG degrees like MD or MS can become a specialist or consultant. However, in the UK , ‘a certificate of completion of training is required to gain a UK consultant position’

Physically handicapped quota

SC: students with low vision can get admission

After paving the way for the colour blind to pursue medical studies, the Supreme Court has now allowed aspiring medical students suffering from low vision to get admission, saying the present law did not bar them from becoming a doctor.

A bench of Justices Arun Mishra and Indira Banerjee came to the rescue of an Ahmedabad-based student who was denied admission in a medical college despite qualifying NEET 2018 with a rank of 419 in the physically-handicapped category.

The court brushed aside the contention of MCI that persons with visual impairment of 40 per cent or more could not be admitted to undergraduate medical courses and the beneficial provision of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, which provides reservation for the differently-abled, could not be invoked in MBBS/BDS courses.

State govt. has power to adjudge suitability of candidate

Merit of disabled candidate not sole key for MBBS seat: HC, August 22, 2018: The Times of India

The Gujarat high court rejected a petition by three disabled students seeking admission in MBBS under physically handicapped quota. The court said the candidate may be meritorious, but the state government has the power to adjudge suitability of a physically challenged person to pursue medical studies.

Ganesh Baraiya, Muskan Shaikh and Hina Mevasiya had approached the HC after the medical board and an appellate authority rejected their case that they are suitable to pursue MBBS. Ganesh was declared 72% disabled with a 109 cm height, while Muskan’s amputated hand left her 75% disabled. Hina was declared 50% disabled due to paraplegia. Their petition cited the Right of Persons with Disabilities Act which states that all persons with a physical disability between 40% and 80% are eligible for admission in medical courses.

Private medical colleges

Can't have own entrance test

The Times of India, Mar 9, 2016

Yogita Rao

The SC move is aimed at checking deliberate suppression of vacancy position in PG seats by the states.