Education, annual reports on the status of: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

2017

A summary

The 2017 Annual Status for Education Report (ASER) has pessimism written all over it. It records how teaching standards are slipping fast, and could soon be under the proverbial duck’s tail. Yet, so strong is their aspiration, that the young keep enrolling; even a hopeless school exudes hope.

This is the silver lining in the dark ASER clouds. The percentage of 18 year olds in educational programmes has risen from a mere 32% in the 2001 census to an estimated 70% according to ASER’s 2017 survey. Are parents of these 18 year olds seeing rainbows at night?

This determination to see their young through schools to a better life is worth every sacrifice. Parents willingly tighten their belts past the last notch to afford private schools for their children. Consequently, the percentage of students studying in such establishments remains high and has stayed that way for some time.

Between 2010-11 and 2015-16 student enrollment in government schools across 20 Indian states fell by 13 million, while private schools acquired 17.5 million new students. In all, according to District Information System of Education (or DISE) data, about 35% of children today are in private schools – a huge jump from the 1980s when the number was just 2%.

All of this is not just an urban phenomenon. The ASER findings show that only 1.2% of youth are willing to work in agriculture and that very few young people want to follow their parents’ dreary professions. The jobs most sought after are in the army and police. Education can help in such aspirations because there is an entry test to pass.

Nor are the young satisfied in being herded into vocational schools. They aspire instead, like most middle class people, to be university graduates. Thus while a minuscule 5.3% of those between 14-18 years of age turn to vocational training, 74% aspire for a bachelor’s degree.

Workers in late 19th century Britain also wanted their children to experience the “luxury” of education. They resented the fact that the posh middle class was slotting them into vocational schools as if they were not good enough for universities. This aspirational urge was also a self-respect movement and out of it came several institutions in England such as the University of Reading.

From this a more robust middle class also emerged in Britain. Instinctively, the aspirational class in India seems to be choosing the same route. In fact, ASER records a substantial jump in the number of graduates and predicts their proportion will double in the next decade. Why should the poor be destined to vocational schools? Can they not dream bigger?

Those that still can’t make it refuse to follow their fathers’ footsteps in the mud. Agriculture is hardly an option and that is why they turn instead to non-farm occupations. No wonder, micro and small industries are sprouting more readily on village soil than wheat and rice. According to the MSME Census, there are more such units in rural than in urban India. Squatting over a loom in a windowless room is preferable to pushing a lifeless plough.

Aspirations can be a powerful motivator of knowledge. While their teachers may not deliver at par, schoolchildren are aware of a wider world because that’s where they want to make a life. Once again ASER figures show that as many as 64% could identify the capital of India. Not just that, 79% knew exactly the state they lived in and 42% could even point it out on a map.

These numbers should not be sneezed at for in developed America, according to a Gallup/Harris poll, 73% of Americans could not identify their home country on a map. Not bad at all; the aspiring Indian village kid scores higher than grown Americans.

The aspiring class in our country is running up the stairs while our so-called middle class is stuck in the lift.

Highlights

This is the twelfth annual report. Every year since 2005, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) has reported on children’s schooling status and their ability to do basic reading and arithmetic tasks. Year after year, ASER has highlighted the fact that although almost all children are enrolled in school, many are not acquiring foundational skills like reading and basic arithmetic that can help them progress in school and life. Since 2006, ASER has focused on the age group 5 to 16.

In 2017, ASER focused on an older age group, youth who are 14 to 18 years old and have moved just beyond the elementary school age.

Near-universal enrollment and automatic promotion through the elementary stage have resulted in more and more children successfully completing elementary schooling. According to official figures from the District Information System for Education (DISE), enrollment in Std VIII almost doubled in the decade between 2004-5 and 2014-15, from 11 million to almost 22 million. According to Census 2011, one out of every ten Indians is currently in the age bracket of 14-18. This amounts to more than 100 million or 10 crore youth in all. For all of these reasons, we felt it was important to look closely at this age group of 14 – 18 year olds.

The 2017 ASER report has made an attempt to look ‘beyond basics’ and explore a wider set of domains beyond foundational reading and arithmetic. Four domains were considered – activity, ability, awareness and aspirations. As before, ASER 2017 too is a sample based household survey, with tasks that are simple to administer and easy to understand. Like in previous years, this ASER too has been conducted with the participation of local partner organizations. Since this is the first time that ASER is focusing on this age group, the assessment was carried out in one or two districts in almost all states of our country. ASER 2017 was carried out in a total of 28 districts of 24 states. About 2,000 volunteers from 35 partner institutions, visited more than 25,000 households in 1,641 villages, surveying more than 30,000 14 to 18 year olds in all.

ASER 2017: KEY FINDINGS

ACTIVITY

Overall, 86% of youth in the 14-18 age group are still within the formal education system, either in school or in college.

• More than half of all youth in this age group are enrolled in Std X or below (54%). Another 25% are either in Std XI or XII, and 6% are enrolled in undergraduate and other degree courses. Only 14% are not currently enrolled in any form of formal education.

• The enrollment gap between males and females in the formal education system increases with age. There is hardly any difference between boys’ and girls’ enrollment at age 14; but at age 18, 32% females are not enrolled as compared to 28% males.

• The proportion of youth not enrolled in school or college increases with age. At age 14, the percentage of youth not enrolled is 5%. By age 18, this figure increases to 30%.1

• Overall, about 5% of youth are taking some type of vocational course. This includes those who are enrolled in school or college as well as those who are not currently enrolled.

• Youth who take vocational courses tend to take short duration courses of 6 months or less. Of those who are doing vocational courses, the highest percentage of youth (34%) are enrolled in courses which are 3 months or shorter, and another 25% are enrolled in courses between 4 and 6 months in duration.

• A substantial proportion of youth in the 14-18 age group are working (42%), regardless of whether they are enrolled in formal education or not. Of those who work, 79% work in agriculture – almost all on their own family’s farm. Also, more than three quarters of all youth do household chores daily – 77 % of males and 89% of females.

ABILITY

For the past twelve years, ASER findings have consistently pointed to the fact that many children in elementary school need urgent support for acquiring foundational skills like reading and basic arithmetic. With this year’s focus on an older age group, it is important to understand the level of basic skills among youth as well as their preparedness for tasks that go “Beyond Basics”.

Ability: Foundational skills

First, let us look at the current status of foundational skills for youth in the age group 14 to 18.

• About 25% of this age group still cannot read basic text fluently in their own language.

• More than half struggle with division (3 digit by 1 digit) problems. Only 43% are able to do such problems correctly. The ability to do division – a task that is usually done in ASER, can be thought of as a proxy for the ability to do basic arithmetic operations.

• 53% of all 14 year-olds in the sample can read English sentences. For 18 year-old youth, this figure is closer to 60%. Of those who can read English sentences, 79% can say the meaning of the sentence.

• Even among youth in this age group who have completed eight years of schooling, a significant proportion still lack foundational skills like reading and math.

Interestingly, although reading ability in regional languages and in English seems to improve slightly with age (more 18 year-olds can read than 14 year olds), the same does not seem to apply to math. The proportion of youth who have not acquired basic math skills by age 14 is the same as that of 18 year olds. Learning deficits seen in elementary school in previous years seem to carry forward as young people go from being adolescents to young adults.

Ability: Applying basic literacy and numeracy skills to everyday tasks

People are expected to do many tasks requiring literacy and numeracy every day. Many young people of this age group are the first in their families ever to complete eight years of schooling.2 So, their ability to do basic calculations and make correct decisions is important not just for themselves but for the whole family.

ASER 2017 explored a variety of such tasks with young people in the age group 14 to 18. In terms of daily tasks, we picked some simple activities like counting money, knowing weights and telling time:

• How much money is this? 76% of surveyed youth could count money correctly. For those who have basic arithmetic skills,3 the figure was close to 90%. (This task involves simple addition.)

• 56% could add weights correctly in kilograms. For those who have basic math skills, the figure is 76%. (This task involves addition and conversion from grams to kilograms.)

• Telling time is a common daily activity. For the easy task (hour), 83% got it correct. But for the slightly harder task (hour and minutes) a little less than 60% got it right.

What about common calculations that people often have to do? For ASER 2017, we picked a few such activities like measuring length with a ruler, calculating time, and applying the unitary method (e.g. deciding how many chlorine tablets to use for purifying water).

• 86% of youth could calculate the length of an object if it was placed at the ‘0’ mark on the ruler. But when the object was placed elsewhere on the ruler, only 40% could give the right answer.4

• How many hours has this girl slept? Less than 40% of all sampled youth could calculate the right answer. Of those who could at least do division, about 55% could answer correctly.

• How many tablets are needed to purify water in the big pot? Again about 50% of youth got this right. For those who could do division, the number is 70%.

A variety of tasks in daily life require reading and understanding written instructions. For example, for prevention of dehydration especially in the case of diarrhoea, oral rehydration measures are recommended. ORS packages are available widely in rural and urban areas.

Packages come with easy to use instructions that are quite straightforward. To assess whether youth are able to read and follow simple instructions, we asked them some questions based on this text. For example: how many packets of ORS should be mixed with 2 litres of water? Within how many hours should the prepared mixture be consumed? How many litres of O.R.S. solution can be given to a 21 year-old within a span of 24 hours? Can this packet be used in December 2018?

• In our sample, more than 75% of youth can read a Std II level text fluently. But only a little over half (54%) could answer at least 3 out 4 questions based on the written instructions on the ORS packet.

• Of those who have currently completed 8 years of schooling or are currently enrolled in school or college, about 58% can read and understand instructions. But only 22% of those who are currently not enrolled can do so.

What are some ordinary, commonplace financial calculations? ASER 2017 included four examples:

• Managing a budget: You have Rs. 50 and you are looking at a rate list for snacks. Which three different items can you buy so that fifty rupees is completely spent?

• Taking purchase decisions: In the second task, you need to buy a set of five books. Two different prices are being offered in two different shops. Which shop will you go to if you want to spend the least amount of money possible? And, how much will you spend?

For both the tasks described above, less than two thirds of youth age 14-18 can correctly do the calculations (64%). This figure roughly corresponds to all those who can at least do subtraction in our sample.

• Applying discounts: The third task consists of a picture of a T-shirt which is on sale with a 10% discount. The task is to figure out how much to pay after the discount. 38% of youth can do this computation correctly.

• Calculating repayment: The fourth task is to decide which bank to take a loan from after comparing interest rates being offered by 3 banks and then computing what would be the repayment amount after a year. 71% youth chose the bank correctly but only 22% could calculate the correct repayment amount.56

What about maps and general knowledge? A map of India was shown to each young person who was surveyed. They were asked a series of questions:

• “This is a map of which country?” 86% answered India.

• “What is the name of the capital of the country?” 64% answered correctly.

• “Which state do you live in?” 79% answered correctly.

• “Can you point to your state on the map?” 42% could do so.

The overall patterns indicate that having basic foundational skills like reading and arithmetic are very helpful even for daily tasks and common calculations. However, not everyone who has these foundational skills can correctly complete these everyday tasks. Similarly, although having completed at least 8 years of schooling is an advantage, not all youth who have done so can do these tasks. Females perform worse than males on almost all tasks. These data show that substantial numbers of young people who have completed 8 years of schooling have difficulty applying their literacy and numeracy skills to real world situations.

AWARENESS & ASPIRATIONS

Each sampled youth was asked a series of questions to understand their access to media, financial institutions and the digital world. As expected, mobile phone usage is widespread in the 14-18 age group. 73% of the young people had used a mobile phone within the last week.

• However, significant gender differences are visible. While only 12% of males had never used a mobile phone, this number for females is much higher at 22%.

• Mobile usage rises significantly with age. Among 14 year-olds, 64% had used a mobile phone in the last week. That figure for 18 year-olds is 82%. But for these young people, the use of internet and computers was much lower. 28% had used the internet and 26% had used computers in the last week, while 59% had never used a computer and 64% had never used internet.

• For those who are currently enrolled in the education system, access to internet and computers is higher than those who are not currently enrolled. However mobile usage is high regardless of whether they are enrolled or not.

• Girls and young women have far lower access to computer and internet as compared to boys. While 49% of males have never used the internet, close to 76% of females have never done so.

As expected, almost every young person (85%) had watched television in the last week. 58% had read a newspaper and a little under half (46%) had listened to the radio in the previous seven days. Gender differences in access to traditional media is seen to be far lower than the differences in access to the digital world.

With respect to participation in financial processes and institutions, close to 75% youth have their own bank account. Interestingly, a slightly higher percentage of females have bank accounts than males in this age group. 51% have deposited or withdrawn money from the bank. 16% have used an ATM or debit card, but only 5% have ever done any transaction using a payment app or mobile banking.

ASER 2017 also asked youth about their study and professional aspirations. About 60% youth in the age group 14-18 years wanted to study beyond Std XII. This percentage is almost half (35%) among youth who could not read a Std II level text fluently.

Professional aspirations are clearly gendered, with males aiming to join the army or police or becoming engineers and females showing preference for teaching or nursing careers. Almost a third of the youth who were currently not enrolled in an educational institution did not have a specific occupation that they aspired to. Finally, 40% youth did not have any role models for the profession they aspired to.

Concluding thoughts

Unless we ensure that our young people reach adulthood with the knowledge, skills, and opportunities they need to help themselves, their families, and their communities move forward, India’s much awaited ‘demographic dividend’ will not materialize. Our interactions with youth in this age group suggest that as a country we urgently need to attend to their needs. ASER 2017 is an attempt to shine a spotlight on this situation and hopefully start a nation-wide discussion about the way forward.

2018

A summary

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Basic literacy, numeracy skills of rural Class VIII students in decline: ASER 2018, January 16, 2019: The Hindu

What is 919/6? More than half of Class VIII students do not know

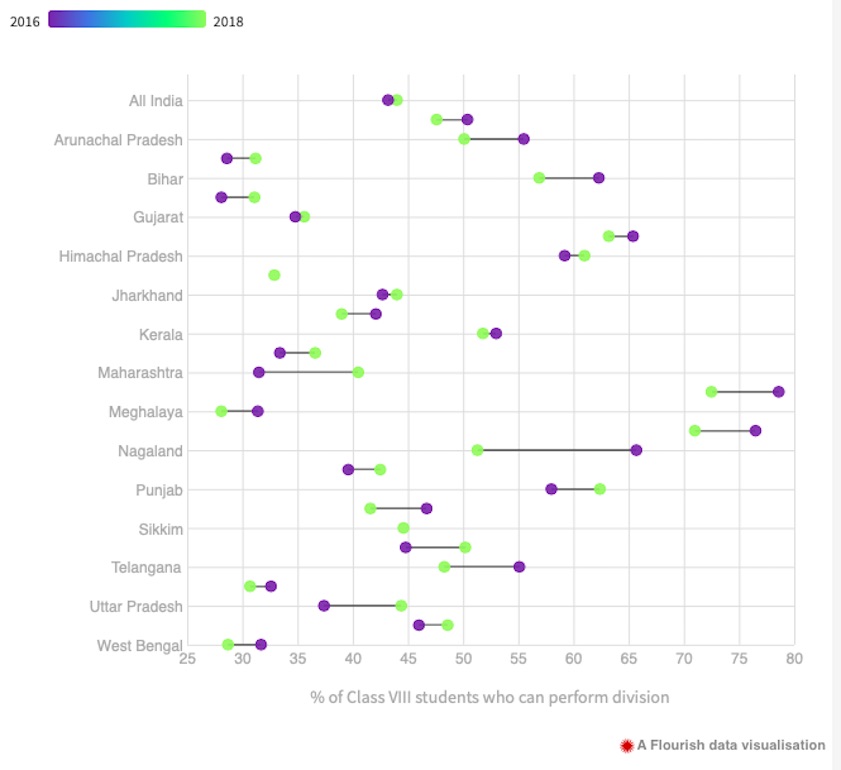

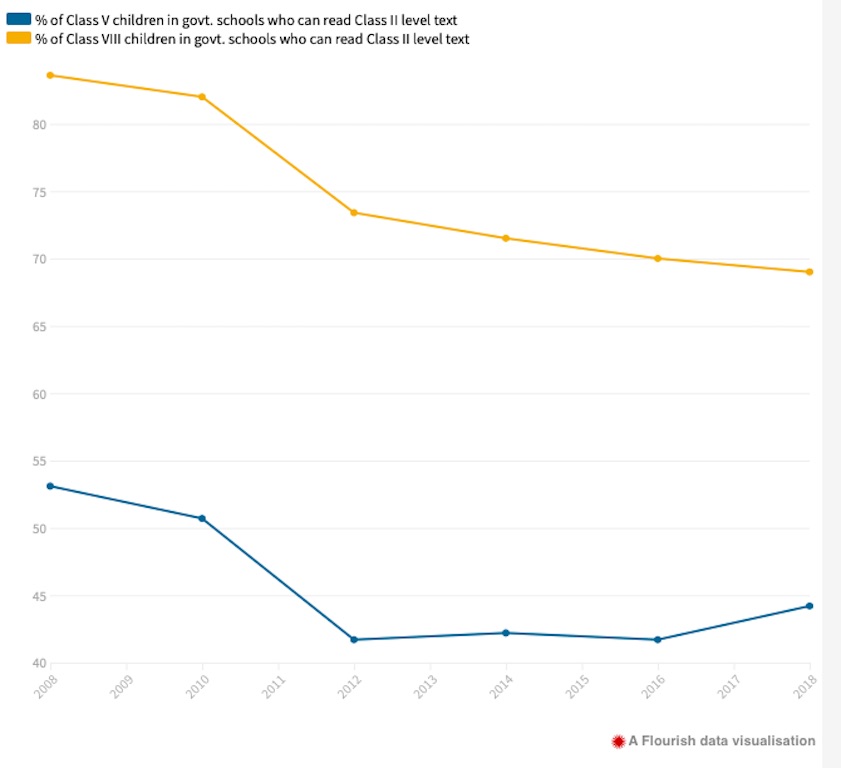

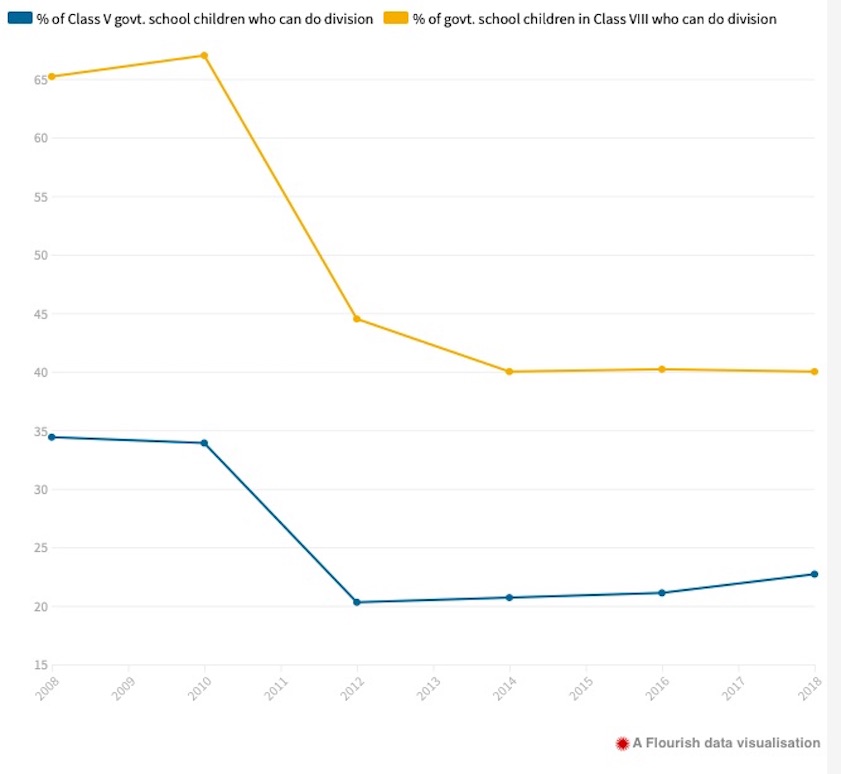

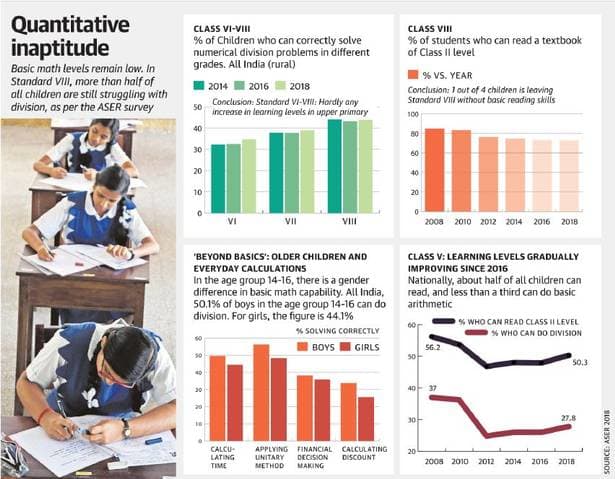

While there has been some improvement in the reading and arithmetic skills of lower primary students in rural India over the last decade, the skills of Class VIII students have actually seen a decline.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2018, the results of a yearly survey that NGO Pratham has been carrying out since 2006, shows that more than half of Class VIII students cannot correctly solve a numerical division problem and more than a quarter of them cannot read a primary-level text.

Those figures are worse than they were a decade ago. In 2008, 84.8% of Class VIII students could read a text meant for Class II; by 2014, only 74.6% could do so, and by 2018, that percentage had fallen further to 72.8%.

Four years ago, 44.1% of students at Class VIII could correctly divide a three-digit number by a single-digit number; in 2018, that figure had fallen slightly to 43.9%.

Noting that the “additional value added in terms of math skills for each year of schooling is low”, Pratham researchers concluded that “without strong foundational skills, it is difficult for children to cope with what is expected of them in the upper primary grades”.

The picture is slightly more encouraging at the Class III level, where there has been gradual improvement since 2014. However, even in 2018, less than 30% of students in Class III are actually at their grade level, that is, able to read a Class II text and do double-digit subtraction. “This means that a majority of children need immediate help in acquiring foundational skills in literacy and numeracy,” said Pratham.

These overall percentages also camouflage wide differences in skill level between States, or even between students in a single classroom.

For example, the ASER data found that almost half of Class III students in government schools in Himachal Pradesh can read a Class II level text, while another quarter can read a Class I level text. This allows the teacher to use grade-level textbooks for most of the class, although the remaining quarter of students will need ongoing support for basic skills.

In government schools in Uttar Pradesh, however, a quarter of students cannot recognise letters yet, while another 37% can recognise letters, but not read words. Urgent and immediate help is needed for these students if they are not to be left behind.

The ASER survey covered almost 5.5 lakh children between the ages of 3 and 16 in 596 rural districts across the country. In an encouraging trend, it found that enrolment is increasing and the percentage of children under 14 who are out of school is less than 4%. The gender gap is also shrinking, even within the older cohort of 15- and 16-year-olds. Only 13.6% of girls of that age are out of school — the first time the figure has dropped below the 15% mark.

See also

Education, annual reports on the status of: India

Education: India (covers issues common to all categories of Education) <> Education: India, 1911 <> Engineering education: India <> Higher Education, India: 1 <> Medical education and research: India <> Primary Education: India <> School education: India (covers issues common to Primary and Secondary Education) <> Secondary Education: India <> Indian universities: global ranking <> Caste-based reservations, India (history) …and many more.