Elections in India: behaviour and trends (historical)

New: Several sections of this page have been shifted to the page Election expenditure: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

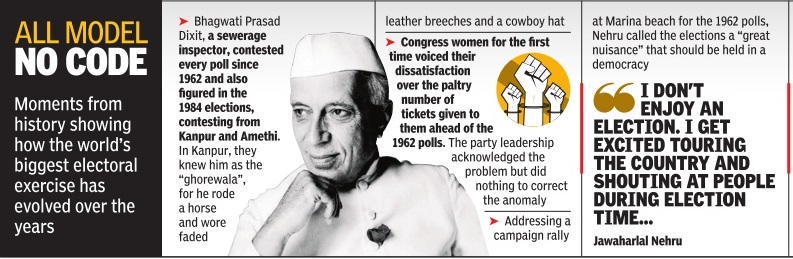

History

General Elections to the Lok Sabha, 1951- onw

The first General Elections were held from 25 October 1951 to 21 February 1952;

the second from 24 February to 14 March 1957;

the third from 19 to 25 February 1962;

the fourth from 17 to 21 February 1967;

the fifth from 1 to 10 March 1971;

the sixth from 16 to 20 March 1977;

the seventh from 3 to 6 January 1980;

the eighth from 24 to 28 December 1984;

the ninth from 22 to 26 November 1989;

the tenth from 20 May to 15 June 1991;

the eleventh from 27 April to 30 May 1996;

the twelfth from 16 to 23 February 1998;

the thirteenth from 5 September to 6 October 1999;

the fourteenth from 20 April to 10 May 2004;

the fifteenth from 16 April to 13 May 2009;

the sixteenth General Elections from 7 April 2014 to 12 May 2014,

the seventeenth General Elections from 11 April 2019 to 19 May 2019 (schedule),

Details 1951 – 2019

Anubhuti Vishnoi, August 17, 2023: The Times of India

As India heads to the 18th Lok Sabha election after 76 years of Independence, the electoral journey travelled by the largest democracy is one marked with many milestones — the largest electorate in the world at more than 900mn; female voters who closed the gender gap in voter turnout in 2019 and outdid males; and the only country to transition to paperless ballots through electronic voting machines (EVMs).

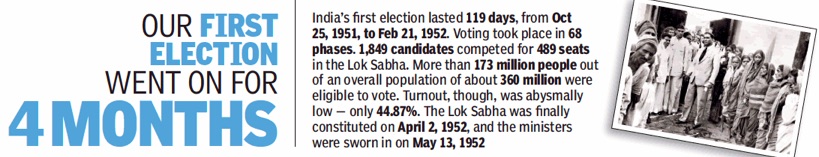

The first general election

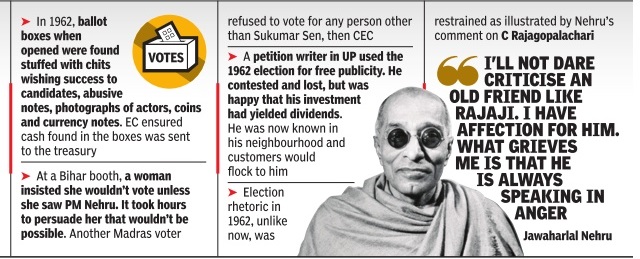

Things moved swiftly in independent India with the adoption of the Constitution on November 26, 1949. Four months later, Sukumar Sen was appointed the first chief election commissioner (CEC). With this, the country embarked on the great experiment to conduct the first nationwide election.

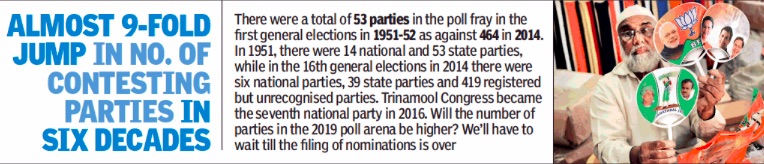

In April 1950, the Representation of People Act was passed by the provisional Parliament. The first general election was held in 68 phases between October 25, 1951 and February 21, 1952. Around 53 political parties and 533 independents were in the fray for 489 seats. Around 173mn voters were registered out of a population of 361mn and 45.8% voter turnout was recorded.

The Indian National Congress wrested 364 of the 489 seats and Jawaharlal Nehru became India’s first democratically elected prime minister.

The first general election was what Sen described as “an act of faith”. Every general election still is.

The genesis of political parties

The first election opened up new political and electoral fault lines and sowed the seeds of a multi-party democracy.

While the Congress won and did so for several elections to come, indicating a ‘national consensus’, new political formations emerged over the following decades.

Of the 14 parties in the fray in 1952, four retained the national status among them, some by ministers previously in the Nehru-led government who had resigned to form their own parties.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee quit Nehru’s provisional ministry to later form the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the reincarnation of which in 1980 was the Bharatiya Janata Party, which has formed five Union governments so far, including the current one.

The Communist Party of India (CPI) also contested the first general election and became the principal Opposition party winning 16 seats. It split in the 1960s and the CPI (Marxist) faction grew stronger in political influence over the years. It supported the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2004 but withdrew support over the Indo-US nuclear deal. It is today allied with the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) and leads the ruling alliance in Kerala, apart from being part of the Nitish Kumar-led alliance in Bihar and also supports the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government in Tamil Nadu.

Law minister BR Ambedkar revived the Scheduled Castes Federation, which later led to the creation of the Republican Party of India that splintered into nearly 50 factions over the years. Acharya Kriplani formed the Kisan Mazdoor Praja Parishad or Praja Party, which merged with Jayaprakash Narayan’s and Ram Manohar Lohia’s Socialist Party to become the Praja Socialist Party (PSP). Many parties formed later had leaders who emerged from the PSP. There were also parties whose fortunes dwindled over the years and others that merged into similar politically-ideological tents. For instance, the Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha of VD Savarkar and Nathuram Godse never notched electoral victories but its strong ‘Hindu rashtra’ underpinnings continue to be reflected in political narratives right into 2023. The Akhil Bharatiya Ram Rajya Parishad (RRP), led by Hariharanand ‘Swami’ Karpatri, also advocated for a ‘Hindu rashtra’. It won three seats in the 1951 polls and later merged with the BJS. The All-India Forward Bloc, founded by Subhas Chandra Bose, survived several splits and is quite diminished in presence and influence. The Revolutionary Socialist Party has also survived many splits and retains its pockets in West Bengal and Kerala.

Alongside, there was also the rise of regional parties. The Shiromani Akali Dal bagged four seats in the 1952 election and remains a critical stakeholder in Punjab.

The Jharkhand Party, set up by Jaipal Singh Munda, contested several assembly elections, demanded statehood for Jharkhand and was the principal Opposition to the Congress in Bihar for several years.

Such changes became deep-driven with alliances and multi-party governments becoming more commonplace as regional and community aspirations found representation in the electoral space. As on date, there are six national parties, 54 state parties and more than 2,500 unrecognised parties in India.

Even in 2023, both the ruling dispensation and the Opposition are alliances stitched up with several parties that have roots in the first general election.

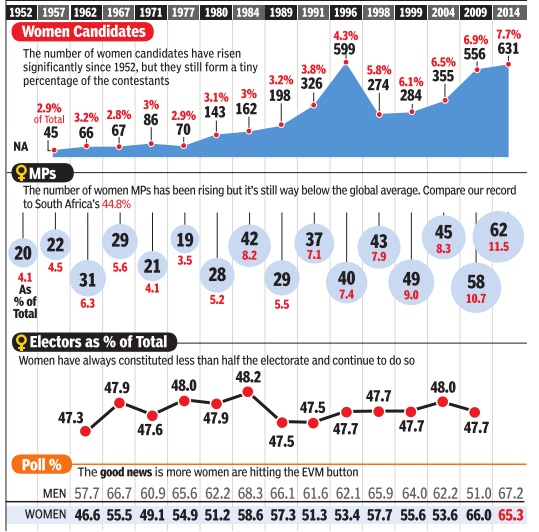

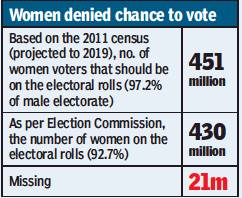

Female voters

India made the big leap with its first election by bringing universal adult franchise — every man and woman over 21 years was allowed to vote. In the late 1980s, the voting age was lowered to 18.

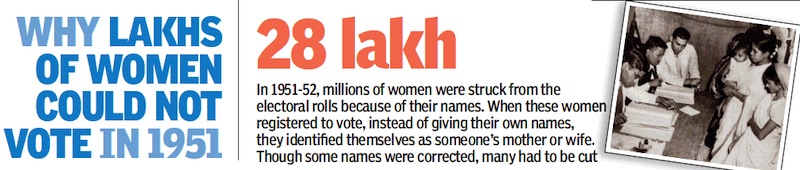

The first general election was challenging, including in bringing female voters to the polling booth. Women of the era refused to give their complete names due to social inhibitions and would refer to themselves as mother of X, or daughter/wife of Y. No such allowance was permitted by Sen on the voters’ list. It is estimated that more than 2.8mn women could not vote in the first election due to this.

Sen, still the CEC into the second general election in 1957, launched massive public campaigns and appealed to women to disclose their full names to exercise their voting right. The next election saw better numbers.

The Election Commission (EC) had to keep at it over the years, methodically addressing various barriers faced by women in participating in elections, from ensuring separate toilets to creche facilities, all-women polling stations and women block-level polling registration staff. And it has worked with phenomenal results.

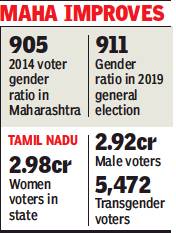

From men, starting at a 16 percentage point edge over women in voter turnout in 1962, the figure was halved to 8.4 percentage points in the 2004 Lok Sabha election and was down to 1.8 percentage point in 2014.

The 2019 Lok Sabha election marked a watershed because females closed the gender gap with male voters. They surpassed them at over 67% turnout. From a gender gap (in female to male voter turnout) of -16.71% in 1962, it not only closed but reversed to +0.17% in 2019, the EC noted. India witnessed a 235.72% increase in female electors since the 1971 election. Women have risen to become an independent and important segment for every political party as the election manifestos clearly indicate.

There is also a rise in the number of women elected to Parliament — from 24 in the first general election to 78 in 2019. This needs to improve as does overall voter turnout — up from 44.8% in the first election to a record 67.4% in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls. The EC is mindful that migrant and young voters are still not exercising their vote, and discussions have been opened to consider remote voting options.

Progress in electoral process

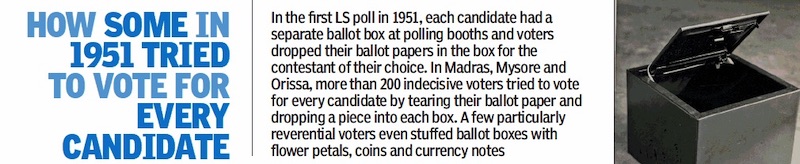

The first general election process involved allotting each candidate a different coloured ballot box with his name and symbol at the polling booth to help even unlettered people to vote. People would cast their vote into the desired candidate’s ballot box. The process took 68 phases of voting.

The 2019 Lok Sabha election was held in seven phases and within 50 days.

The nation moved fast from this setup. Almost every election has seen a reworking of processes which are now well-etched into the electoral machinery — from preparation of electoral rolls, their summary revision, mapping of vulnerable polling stations, ensuring adequate security deployment among others. There are also fully home-grown technological innovations that are today integral to the poll process.

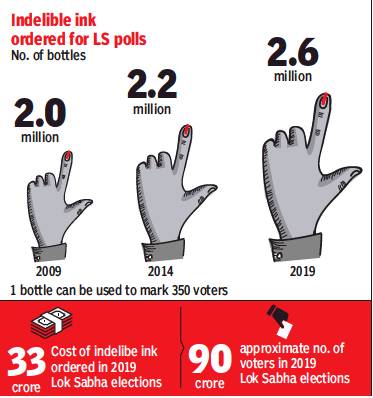

The first challenge encountered by the EC was identity theft and multiple votes by a single voter. The indelible ink was brought in for this. Developed with the help of the National Physical Laboratory, the indelible ink was first used in the 1962 election and is still key proof to a voter having cast the vote.

The most tectonic shift in the electoral landscape came in the late 1990s when the electronic voting machine (EVM) was introduced. The ballot paper had acquired notoriety over ballot loot and manipulation of votes across several states.

The EVM became the only voting method for general and assembly elections in 2004 and is credited for stamping out the booth-capture model of electioneering of the 1980s. Alongside the EVM came the voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT) to help a voter verify the candidate and party he has voted for and dispel impressions on possible hacking of EVMs.

Piloted in the Nagaland polls in 2014, the VVPAT has been used in all assembly and Lok Sabha polls from 2019. Following an SC order on April 9, 2019, the EC also increased the VVPAT slips vote count to five randomly selected EVMs per assembly constituency. The EVM-VVPAT combine has been questioned by several cynics, but continues to stay. The 2024 Lok Sabha election will see EVMs deployed in its latest avatar — the M3.

Electronically transmitted postal ballot papers, meant to service voters on duty away from their place of domicile, have more recently been extended to senior citizens, which is said to have improved their participation in polls.

Still miles to go

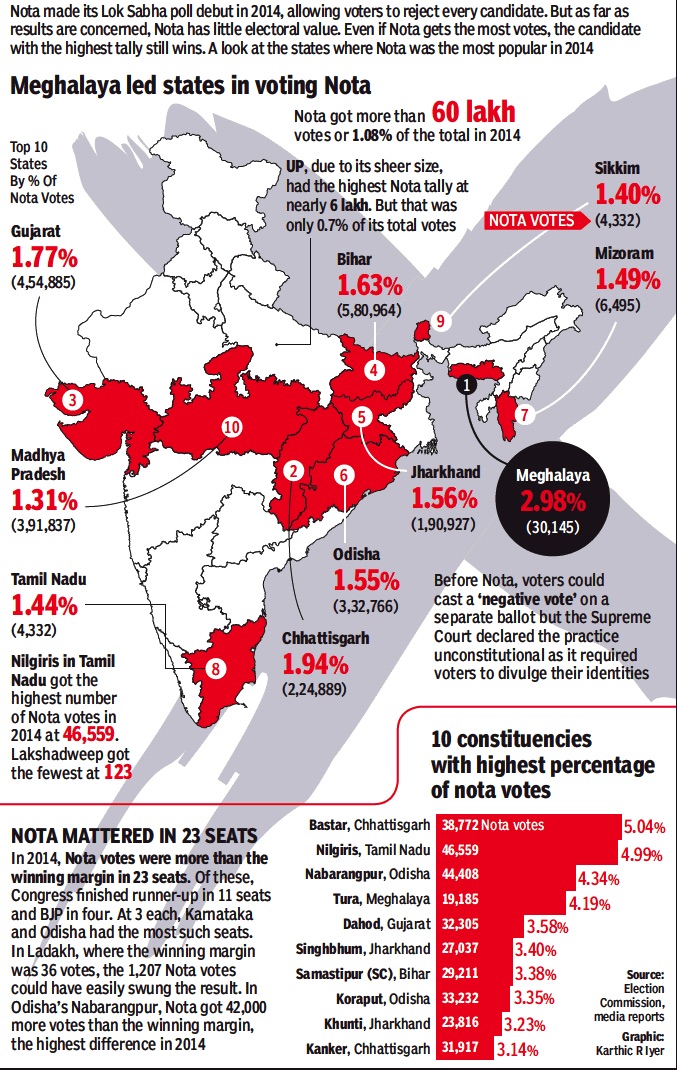

Courts have often stepped in on behalf of voters. In 2013, the Supreme Court allowed citizens to cast a negative vote — ‘None of the above’ (Nota).

Courts have also intervened to ensure greater voter awareness. On its orders, each candidate must declare his criminal antecedents in his poll affidavit.

However, attempts to ensure migrant voting through options like remote voting or for non-resident Indian (NRI) voters have not succeeded so far. Similarly, while the Model Code of Conduct came into effect from the 1962 election, it is found deficient in checking hate speech, bribing of voters and the influence of money power in elections.

While the symbols order of 1968 and the anti-defection law of 1985 have tried to combat “the evil of political defections” in the lure of office, that has not stopped splits or defections. The EC, Law Commissions, governments and courts have made recommendations to usher in greater transparency in the electoral system from aspects such as funding to checking criminalisation. Although much has been achieved, much more is waiting to be done. There’s a list of more than 50 electoral reform recommendations that the EC sends to every government, year after year.

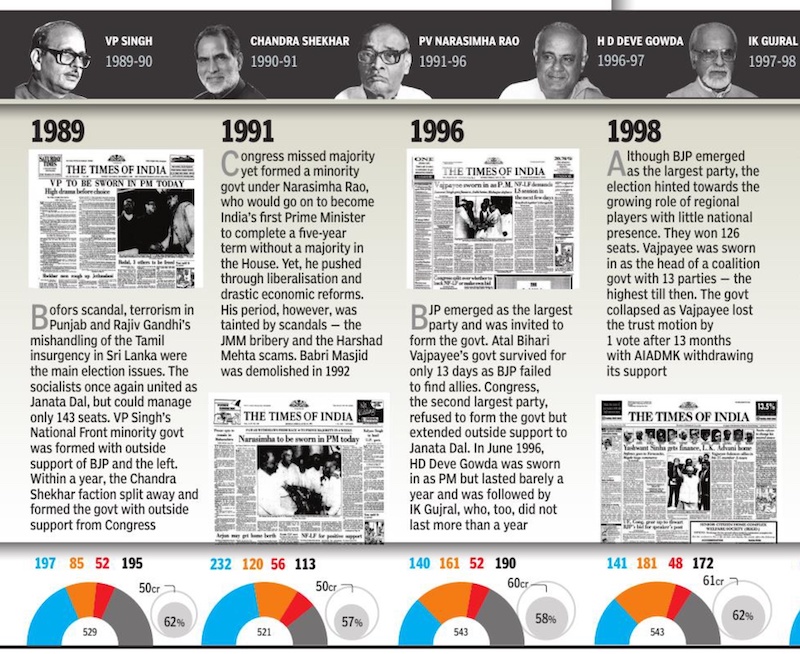

The results: 1951-2024

From: March 17, 2024: The Times of India

From: March 17, 2024: The Times of India

From: March 17, 2024: The Times of India

From: March 17, 2024: The Times of India

See graphics:

Lok Sabha elections, parties and seats, 1951- 67

Lok Sabha elections, parties and seats, 1971-84

Lok Sabha elections, parties and seats, 1989-98

Lok Sabha elections, parties and seats, 1999-2014

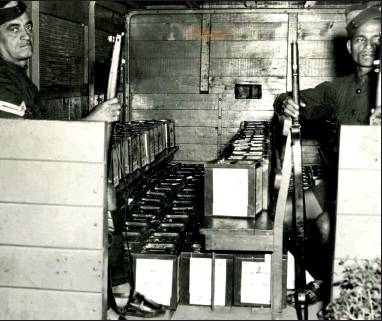

1951: ballot boxes by Godrej & Boyce

From: Bhavika Jain1, This Bombay factory made ballot boxes for India’s first poll, March 17, 2019: The Times of India

Independent India was gearing up to hold its first elections in 1952 and inside a factory in the marshy suburbs of Mumbai’s Vikhroli, the workers were making history, literally.

It was the latter half of 1951 and from the outside, it was business as usual at Plant 1 of the Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd. But unbeknownst to many, the workers were part of a nationbuilding project, assigned the task of speedily manufacturing the first ever ballot boxes to be used in general elections in India.

Archives of the company indicate that a total of 12.83 lakh ballot boxes were produced in the Vikhroli factory in barely four months. “A newspaper, Bombay Chronicle, had printed an article on December 15, 1951, saying the factory was manufacturing 15,000 ballot boxes a day.

This, without affecting the production of any of their other products like safes, cupboards, cabinets and locks, proves that the workers at the factory were putting in extra hours every day to ensure that the ballot boxes were readied in time,” said Vrunda Pathare, chief archivist at Godrej.

An official from the archives division said an ad in The Times of India published by Godrej shows that the original order was for 12.24 lakh ballot boxes but they ended up making 12.83 lakh. “It’s probably because orders were given to other companies as well and those who did not finish them in time passed the order on to Godrej in the end,” said the official.

The production cost of one ‘olive green’ box came to Rs 5 and the model was finalised after testing 50 designs. The internal locking system in the ballot box was designed by a factory hand, Nathalal Panchal, after it was found that an external lock would inflate the making cost.

“We have anecdotal evidence that Panchal played a key role in suggesting the design for the internal locking mechanism,” said Pathare. That story is now part of an oral history project of 2006 when company officials interviewed KR Thanewala, the plant manager of Plant 1 in 1951, who is now no more. Thanewala had recalled during the interview that Plant 1 had just started in May 1951.

“Pirojsha Godrej (the owner) would come to the factory at 3 o’clock every afternoon asking us how it was going. And he got orders from other companies who had not somehow or the other managed to make them (ballot boxes). The mechanism was tested. Every box had to be checked. Click when it closes and click it should open. Once it was closed, without putting your finger inside and pulling the string, you cannot unlock it,” he said.

By February 1952, all the ballot boxes were manufactured, loaded onto railway wagons and sent to the 22 states in preparation for the holding of the polls. Thanewala, in his interview, describes how the boxes were moved: “...We had to walk to the station and back. And...I did a lot of night shifts. At night we (used to) light mashaals (torches) and with the mashaal, I used to walk from the railway tracks up to Vikhroli station. It was great fun.”

1951: many did not know how to vote

From: March 15, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

In 1951 many did not know how to vote

The major political parties

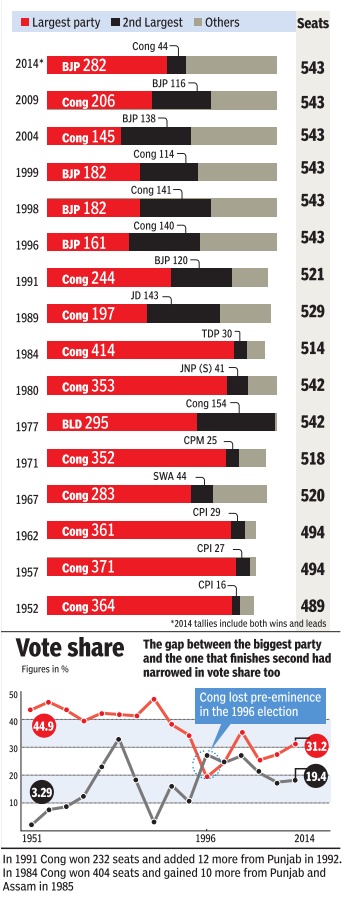

1952-2014: The two biggest parties

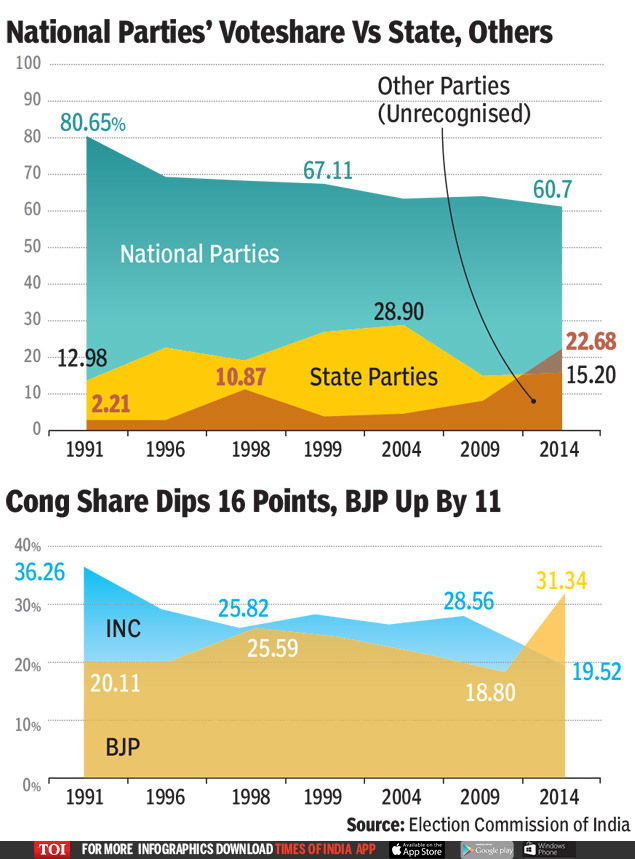

MIND THE GAP

The Times of India May 17 2014

It was a Congres show in the initial elections. By the late 1980s, the picture began to change. With a fragmented polity, coalition governments became the norm. After 25 years, BJP has changed the script winning a decisive majority

2014>2019

From: April 16, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

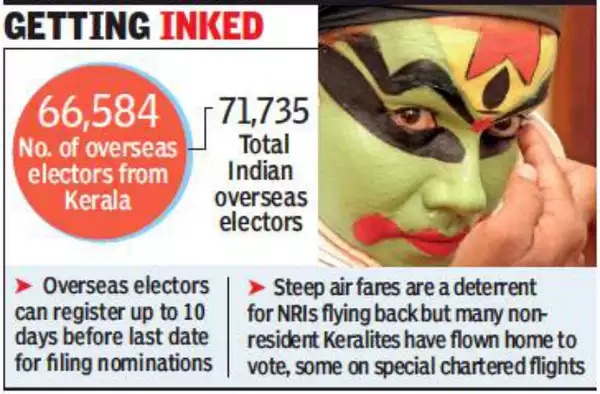

The number of registered and/ or recognised political parties in India, 2014>2019

Big data

2014-19

Shubhra Pant, (Additional reporting by Swati Mathur), April 16, 2019: The Times of India

Why this is India’s big data election

You may struggle to read your neta’s mind but the neta has a lot of help reading yours.

This election season, you may have noticed a trend in the kind of political videos popping up on your feeds. And posts related to polls you haven’t participated in but are there for your reading anyway. You might have also noticed ads from election candidates in your vicinity. And when you want to find out what’s trending? There’s a pattern there too, right?

While reading about elections in newspapers, you may have come across a story about the explosion of ‘Gully Boy’ rappers with their politics-themed numbers on Kolkata’s hip-hop scene. What you wouldn’t have known is that West Bengal is among the largest consumers of political videos in the country.

It shows how one trend begets another — in this case, a certain kind of online behaviour creates a demand, and as more videos are produced because of that demand, it drives up the trend line of the behaviour itself. And the politician who has access to this data would know that while the best way to a Bengali’s heart may be through food, the best way to her or his brain is through videos. Trust the WhatsApp group admins to make full use of that.

Pratham Mittal of the Neta App says of the 90 crore voters in India, around 54 crore are unique mobile phone users who have Facebook and WhatsApp accounts, quoting a McKinsey report. “An analysis shows around 30% of the total voters can be influenced with the use of social media in these elections,” Mittal says.

The ongoing Lok Sabha polls may or may not be an election for a new India, but they certainly are an election that’s about Big Data and its consorts — algorithms, analytics and artificial intelligence (AI). They are invisible but everywhere, creating endless patterns of political messaging around you by relentlessly tracking and decoding your online activity. In election season, when the neta wants to be in your head, this Big Data is worth its gigabytes in gold because it allows customised campaigns, just like targeted ads.

For example, if you have interacted with BJP posts of late, the algorithm would know if the nationalism message is for you. Similarly, how you react to Congress’ pet issues would tell the AI whether you like NYAY.

Poll pitch from data

Both national and regional parties are working with huge data sets of online behaviour to understand household and booth-level profiles in a constituency, first-time voters, floating voters, demographics, caste and socio-economic segments. This data is guiding campaign strategy (not only what to talk about but also what not to), selection of candidates as well as building a pro-party narrative.

Congress has given all its candidates a data docket for each constituency. Praveen Chakrabarty, chairman of Congress’ data analytics department, says the dockets have information on households, new voters, missing voters and local issues. “Instead of pushing down a single leader’s message using technology, we empower our party workers with data and technology. These workers pass on personalised or customised messages to voters.” The party tracks its on-ground activity through the Ghar Ghar Congress app.

But BJP is well ahead of others in using Big Data. It started using analytics in the 2014 general election when others were still grappling with the digital medium. But the technology five years ago wasn’t as advanced as today, when it has opened up new avenues to understand voters. Shivam Shankar, a poll strategist who worked with BJP in Manipur and Tripura in 2017 and 2018, and is now with the Grand Alliance in Bihar, says BJP has first-mover advantage. “BJP has around 25,000 WhatApp groups in all northern states whereas, by the time Congress came to forming such groups, the policies were changed by the social media giant. So, there is no way for Congress to match BJP’s reach,” says Shankar.

More personalised, the better

He says besides polling booths and caste, parties also collect data on utility bills (like power bills, which give an idea about the socioeconomic status of a voter). According to Shankar, the game-changer for BJP will be its latest campaign to target beneficiaries of government schemes. “BJP is working on data of beneficiaries of schemes like Ujjwala, which has never been done before. The data is used to approach voters and convince them to vote for the party,” he says. A BJP MLA from the northeast says analytics are also in pace to study conversations on social media WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook. This not only gives the party an idea about the “narrative” but, with its formidable digital network, allows it easily turn a conversation into a social media trend.

AAP, meanwhile, is working with a team of data researchers and scientists to design its poll strategy. “We use data to identify volunteers at the booth level, which are the booths where AAP is strong and which ones are floating booths and optimise our resources,” says Ankit Lal, who oversees analytics and IT.

Another party which has extensively used social media to canvass is Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP (though it’s now locked in a legal battle with Telangana over voter data). “the village and mandal-level committees upwards, we have party agents who use technology to target people about things we have promised and delivered,” says TDP spokesperson Rammohan Rao.

In Tamil Nadu, DMK has been using the digital medium to court first-time voters. “A team of IT personnel segregates information based on the target audience — youth, IT professionals, entrepreneurs, students and so on — and our messaging to them is tailored accordingly,” says TKS Elangovan, Rajya Sabha MP and organisation secretary of DMK.

SP is using Akhilesh Yadav’s social media popularity to explain the “importance of gathbandhan”. Its spokesperson Abhishek Mishra says, “In the Hindi belt, Akhilesh’s social media following is among the highest. The feedback, along with daily meetings, is what we use to convey that this election is not just a battle of politics and polity, but of ideology and philosophy.”

Enter, the startups

The same analytics that help a company sell toothpaste or Bluetooth speakers are being used by parties to peddle their poll pitches. But the need for expertise to sharpen their messages, and do it across a vast and bewilderingly diverse country like India, has taken them to specialists and startups.

Silver Push, a Gurgaonbased startup which is working with Congress, is doing a sentiment analysis of voters, using keywords. “Once the party has rolled out a campaign, we analyse its success. Then we share this information with the party, which helps them tweak their campaign wherever required,” says Hitesh Chawla, co-founder of the startup, which also analyses videos.

Others like Bangalorebased Next Election, Noidabased Vidooly and Delhi-based Neta App are also working with election-related data. The Next Election app is a bridge between candidates and voters. Amit Bansal, founder of the app, says voters have three tabs — discovery, accountability and contribution. “Constituencies and education of candidates come under discovery while accountability covers work done by candidates. Under contribution, candidates can communicate their message to voters through the app,” explains Bansal, adding he is working with multiple candidates across political parties, and also those contesting in Bangalore.

The Neta App, founded in January 2018 by Pratham Mittal, currently has a 55-member team. It allows users to rate and review their MPs and MLAs, handy data for political parties. The company says in the Karnataka elections, 90% of candidates who won were also rated highest on the app.

Vidooly’s analytics, meanwhile, tell them which political videos are gaining maximum traction, which it then shares with advertisers. “Our current study shows UP, Maharashtra and West Bengal see maximum consumption of political videos. And FMCG is the biggest investor in advertisements,” says Subrata Kar, founder of Vidooly. Founded in 2014, Vidooly analyses online video viewership for various companies.

2019

April 5, 2024: The Times of India

From: April 5, 2024: The Times of India

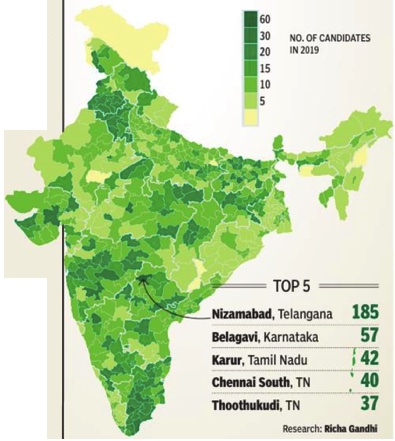

1 vote, 185 candidates

Electors in Telangana’s Nizamabad constituency were really spoilt for choice in 2019. After all, they had a field of 185 candidates from which to pick their representative. Belagavi in Karnataka, too, had a heavy roster of LS hopefuls, though a distant second to Nizamabad. Meghalaya’s Tura, on the other hand, had the smallest candidates’ list, with only three names on it.

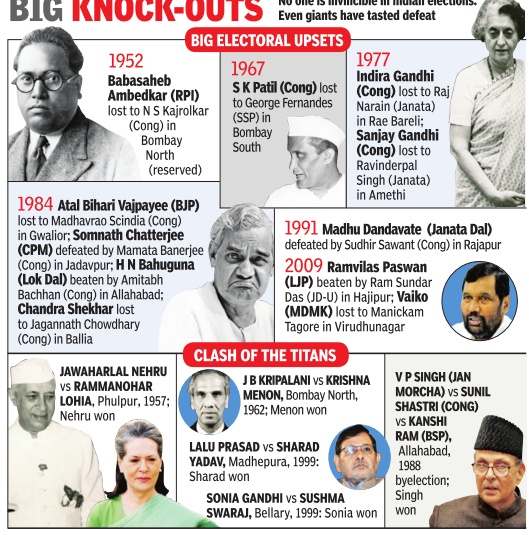

The biggest electoral clashes

1952-2009

Courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic:

Goliaths felled, 1952-2009

Candidates

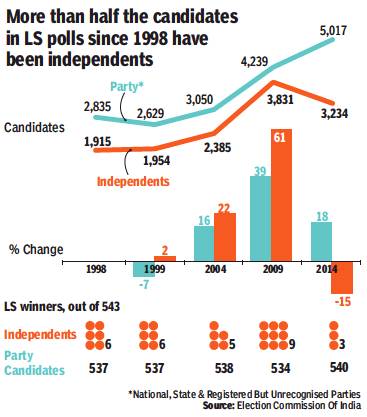

1998-2014: no. per constituency; non-serious candidates

From: Chethan Kumar, Why the outcome doesn’t matter for these poll candidates, March 21, 2019: The Times of India

Talk about participating being more important than winning and there is the case of independent contestants and those from smaller outfits in Indian elections, who make little impact cumulatively as an electoral group but continue to jump into the fray in numbers.

A total of 31,154 candidates (party-affiliated and others) contested in the past five Lok Sabha elections. About eight in 10 of these, or 25,478 candidates, forfeited their deposits with independents and members of smaller parties making up the bulk of their numbers.

Elections are getting more expensive to fight and the electorate rarely chooses a contestant from unrecognised parties or an independent as their member of Parliament. Despite this ground reality, the average number of candidates per constituency has jumped by 70% in 2014 compared to 1998.

In 1998, the average number of candidates per constituency was 8.7, rising to 15.2 in 2014. The maximum number of candidates in one constituency was 34 and 42 in these years, respectively. The average has increased every election since 1998 (see graphic).

“For many, it is a way to gain popularity locally. They know they won’t win, but they want to make themselves known and gain influence in whatever way possible. In some cases, such candidates are later seen associated with major parties,” said political scientist Suhas Palshikar.

Since India follows a firstpast-the-post system, where a candidate with the maximum votes among all contestants wins — even if she or he doesn’t recieve a majority of the votes — many contestants are in it on a gamble.

While some are proxies of major parties looking to divide votes or plain political rebels, some are contesting to make a point.

Take the example of Sumalatha in Karnataka. The wife of late actor-politician MH Ambareesh, she announced on Monday that she would contest as an independent from Mandya, where state CM HD Kumaraswamy’s son Nikhil is making his LS poll debut. Ambareesh was a Congress member and Sumalatha had been looking to get a ticket from her late husband’s party. But Congress ceded the seat to JD(S) as part of its seatsharing pact with the regional party, prompting Sumalatha to declare she would nonetheless join the fray in Mandya.

But many of the new parties cropping up before elections — the number of parties registered with the Election Commission has increased from 1,709 in 2014 to 2,354 as of March 10, 2019 — are seen as proxies by experts. Analysts say the number of “serious candidates” in every constituency is only three or four.

Among 10 major states — Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Delhi — Tamil Nadu and Delhi, at 21, had the highest average of candidates per constituency in 2014.

“There are multiple reasons for a large number of people contesting elections, but key among those is the return on investment that politics offers in developing countries like India,” said political analyst Harish Ramaswamy. “Whether it is in the decentralised institutions or at the national level, people’s economic condition strengthens very quickly and their lifestyle changes.”

Elections are getting more expensive to fight and the voters rarely elect an MP from unrecognised parties or an independent. Despite this ground reality, the average number of candidates per constituency has jumped by 70% between 1998 and 2014

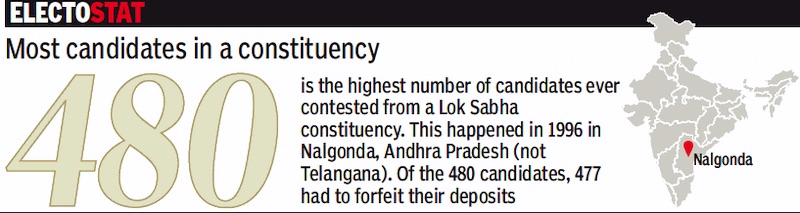

1996: Nalgonda

From: April 1, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

1996: Nalgonda holds the record for the highest number of candidates per constituency

Non-serious candidates

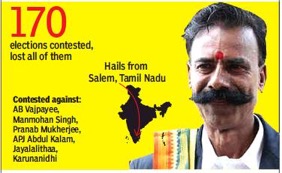

1988-2018: Padmarajan lost 170 elections

March 29, 2019: The Times of India

From: March 29, 2019: The Times of India

Some never tire of trying. Like, Dr K Padmarajan. Starting 1988, the man from Salem, Tamil Nadu, has contested 170 elections. And the 60-year-old has lost all of them. The Limca Book of Records names him as 'India's Most Unsuccessful Candidate'

Dr Padmarajan, a homoeopathic doctor-turned-businessman, has labelled himself as ‘All India Election King’. He has contested not just local and parliamentary but also Presidential elections. Forfeiting his deposit is obviously not a matter of serious concern for him (From The Times of India)

Kashyap: every election makes him poorer

With no cash and zero balance in his bank account and his wife’s, a 51-year-old advocate from Muzaffarnagar constituency is perhaps the poorest candidate in the fray in this Lok Sabha election.

At first glance, there is little to differentiate Mange Ram Kashyap from several other advocates clad in black robes that crowd the Muzaffarnagar court on a daily basis. But ask anybody in the premises and they would tell you that Mange Ram is also a neta who has fought all of the general elections since 2000. Mange Ram contests elections from a party named Mazdoor Kisan Union Party which he founded in 2000. The party has 1,000-odd members, most of them labourers, according to Mange Ram.

In his election affidavit submitted recently, Mange Ram has declared that he has no jewellery, no cash and zero money in his bank account. His wife, Babita Chauhan, also has no cash, no jewellery and no money in her bank account. He does own a 100sq yard plot now valued at Rs 5 lakh and a house built on 60sq yard with an estimated current value of Rs 15 lakh. The house is a gift from Mange Ram’s in-laws. He also owns a bike worth Rs 36,000.

While his political dreams may be taking a long time to materialize, it has done little to deter Mange Ram from campaigning on foot in the city. “I have a bike but I cannot afford petrol for it every day. My wife is a homemaker and we have two kids to take care of. I have tried to find other jobs but there are hardly any,” he told TOI.

“In the last elections too I went on foot to appeal to people to vote for me. I wonder why big politicians spend so much on campaigns when that money could be used for welfare of people,” he said.

But has his door-to-door campaign worked its charm on the voters in the past? The candidate has had to forfeit his deposit every single time as he was unable to secure the minimum number of votes.

Mange Ram is, however, convinced that things will change for the better this year for him. He is also unfazed that he is pitted against heavyweights like BJP’s Sanjeev Balyan, Ajit Singh fielded by SP-BSP-RLD’s alliance and Congress’ Narendra Kumar.

“Voters know that politicians have not looked out for them. I will help the poor. I will propose a voter pension scheme so no man is in want of money,” he said.

Some famous cases

Avijit Ghosh, April 28, 2019: The Times of India

Additional reporting by Binay Singh in Varanasi, Senthil Kumaran in Salem, and Kumar Rajesh in Bhagalpur

These ‘dhartipakads’ are the world’s biggest election losers

From Varanasi’s Adig to Salem’s ‘Election King’, meet the incorrigible poll fighters who have no qualms about losing their deposits

Long before Narendra Modi discovered Varanasi as an election destination, the city of piety had Narendra Nath Dubey ‘Adig’. Often referred to as Kashi’s Dhartipakad, he has been fighting every election as an independent since 1984. And every time he has lost his security deposit. “Victory or defeat is irrelevant to me. I contest elections to make everyone laugh and live stress-free. And I will continue to do so till my last breath,” says the 53-yearold lawyer, a veteran of innumerable contests, including five battles to be the President. On Thursday, Adig (The Unrelenting) dressed up as Lord Ram before filing his papers to take on Modi.

Adig belongs to a select group of oddballs who are as addicted to filing nominations as Navjot Singh is to Sidhuisms. In a country where the general elections are the closest to a people’s festival, they personify its maverick soul, encapsulate its never-say-die spirit. Most of them are referred to by a common moniker, Dhartipakad. Translated literally, Dhartipakad means one who clings on to the earth. The word suggests both tenacity and defiance. There was even a television satire by that name. It’s possible to dismiss these unusual candidates as mere attention seekers who receive disproportionate media spotlight compared to the few hundred or less votes they fetch. But it can be also argued that these eyeball-grabbers — some of whom claim to have contested 200-300 polls at various levels — represent the quintessential spirit of Indian democracy, where even the dissenter or the jester is offered space.

In his book, Ballot: 10 Episodes That Shaped India’s Democracy, journalist Rasheed Kidwai writes about Chowdhry Hari Ram, a farmer from the Rohtak area, who fought the presidential polls in 1952, 1957,1962, 1967 and 1969, sometimes getting no votes. “He was the original Dhartipakad,” he says.

But the threesome who epitomised the non-conformist spirit through the 1960s and later were: Textile businessman Kaka Joginder Singh, cloth merchant Mohan Lal of Gwalior and trader-social worker Nagarmal Bajoria of Bhagalpur. Singh was born in Gujranwala, and Bajoria in Lahore in undivided India. Of the three, only Bajoria survives.

Other than their obsession with contesting polls, the Dhartipakads shared no unifying strand. In an interview to news agency UNI in February 1998, Singh promised to repay all foreign loans, inculcate sterling character in children, and bring back the barter system to cure the ills of the Indian economy in his ‘manifesto’. The Bareillybased businessman also said that losing the security amount was his ‘humble contribution’ to the national fund. Singh, who reportedly distributed sweets after defeat, died the same year. Social scientist Ramchandra Guha mentions Lal, who contested against five Prime Ministers, in his book, India after Gandhi. “Wearing a wooden crown and a garland gifted by himself, he would walk the streets of his constituency, ringing a bell…His idea in contesting elections, said Mohan Lal, was ‘to make everyone realise that democracy was meant for one and all’,” he wrote quoting from The Telegraph newspaper.

The reasoning of such individuals, explains political scientist Imtiaz Ahmad, emerges from the fact that ours is a protesting society and elections for many are an occasion to express dissent. “Contesting an election for them is to make a political statement that all candidates are no good and they are standing to show that democracy is a farce. They have no impact whatsoever. Once the election is over they recede in the background. They are protesters and that’s the only role they play,” he says.

There were other motivations too. For Mitt Singh Sehjara, contesting elections was a passion, as he had told a TOI reporter in 2012. Even during the period of violent militancy that engulfed Punjab, the army man who had fought in the 1962 war against China filed his papers from seven constituencies. The veteran of 42 elections passed away in 2014.

Shyam Babu Subudhi, 84, a resident of Odisha’s Berhampur who has contested 32 elections since 1962 and lost every one of them, told ANI that he has to “continue the fight against corruption” even if he loses his deposit. His most memorable contest was the one against the then Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao for the Berhampur seat.

‘Election King’ K Padmarajan of Salem says he fights to create the awareness that anyone can contest polls. “It is the right of every citizen of India,” says the 60-year-old tyre retreader who filed his papers for the 201st time in Wayanad for the same seat as Congress president Rahul Gandhi. Other star rivals in the past: P V Narasimha Rao, M Karunanidhi, J Jayalalithaa, S M Krishna and many more.

Padmarajan, who has spent nearly 30 lakh in 30 years on elections, claims to occasionally receive threatening calls. “I was kidnapped in 1991 after I filed my nomination in Nandyal constituency in Andhra Pradesh. I don’t know who the kidnappers were but they let me go,” he says.

But perhaps the most remarkable example of persistence and commitment to the ballot is Bajoria, now 94 and ready to contest from Patna and Delhi next month. Also known as a social crusader — for digging tubewells and paying for marriages of underprivileged girls — Bajoria has contested Lok Sabha polls against Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, Sanjay Gandhi, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L K Advani, among others.

“Skewed politics based on party lines, fragmented society, caste, creed and religious divisions create revulsion. It instilled in me a desire to contest elections and spread the message of nationalism, unity and brotherhood,” says Bajoria, who fought his first election against V V Giri in 1969 and has since contested from most states, including Jammu and Kashmir.

In his younger days Bajoria often went to file his nomination accompanied by a drove of donkeys. Says Kidwai, “For him, the donkeys were symbolic of political leaders who fooled people with false promises.”

Caste, religion: the use of

The ‘upper’ castes: voting behaviour

What Johnny won’t see? Upper caste votebank

Why is the support of upper castes for the BJP secular, but that of Muslims for any party communal?

Ajaz Ashraf The Times of India

The 2009 National Election Study, which the Centre for the Study of Developing Studies (CSDS) carried out. It shows 44% of upper castes voted the NDA, down by 9 % from 2004, but the BJP’s decline was just 4%. The UPA bagged 33% of their votes, the Left 10%, the BSP 3%, and Others, a category comprising parties neither in the UPA nor the NDA, 12%. In the 1999 elections, the BJP alone bagged nearly 50% of upper caste votes. [This indicates] an upper caste consolidation

But the incidence of consolidation is far more among other groups, [detractors argue]. The same CSDS study shows 31% of upper OBCs voted the UPA, 27% the NDA, 3% the BSP, 2% the Left, and 37% Others. Take the Dalits, of whom 34% voted the UPA, 15% the NDA, 11% the Left, 21% the BSP, and 20% Others. As for the Muslims, some 47% voted the UPA, of which the Congres bagged 38%, 6% the NDA, 12 % the Left, 6% the BSP, and 29% Others.

This statistical evidence tells a few things. One, other social groups boast as diverse a voting pattern, if not more, as existing among upper castes. Two, voting patterns among all social groups fluctuate over elections. Three, every social group is strongly inclined towards one or two parties which it believes represents its interests.

The tendency to search for Muslim consolidation dates back to the Mandir-Mandal politics, which saw upper castes in significant numbers desert the Congrss for the BJP. But their heft was diminished because Muslims and Dalits, who had sustained Cogress domination for decades, didn’t follow them into the BJP. The myth of Muslim consolidation helps spawn mobilisation of Hindus to offset the numerical disadvantage of upper castes, among whom the BJP is most favoured.

True, Muslims vote tactically in every constituency to vanquish the BJP.

The author is a Delhi-based journalist

Laws, SC rulings fail to stop election casteism, communalism

Dhananjay Mahapatra, April 15, 2019: The Times of India

Leaders of South Sudan were in for a surprise during their recent ecumenical retreat in Rome. Pope Francis knelt down and kissed the shoes of two rival politicians. The Pope’s unique gesture was an attempt to encourage peace in a country which has seen more than 400,000 people killed in a civil war since independence in 2011.

Legally, it is impermissible to mix religion and politics in most countries, including India. There will be an uproar if any top political leader in India goes for a religious retreat. And it looks a remote possibility for any religious leader to kiss the shoes of our political leaders to persuade them to refrain from whipping up religious, communal or casteist emotions during campaigning for general elections. Why would they, when political leaders are queuing up to kiss the feet of religious leaders to improve their election prospects, apart from attempting to appease the gods and goddesses every now and then.

In India, secularism is the core of the constitutional scheme of governance. But on the ground, this core philosophy has always been wounded by parties, howsoever the political leaders may filibuster about adherence to the constitutional ethos.

To overcome the deepseated societal division on the basis of caste and religion, Section 123(3) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, prohibits a candidates from making systematic appeal to vote on the ground of caste, race, community or religion by terming such action as corrupt practice which would render the candidate disqualified.

Amendment to Section 123 (3) in 1956 broad-based the ambit of the provision by including not only the candidate but his agent or any other person. After two more amendments, the law as it stands today was amended in 1961 and reads, “The appeal by a candidate or his agent or by any person with the consent of the candidate or his agent to vote or refrain from voting for any person on the ground of religion, race, caste, community or language or the use of religious symbols or the use of, or appeal to, national symbols, such as national flag or the national emblem, for the furtherance of the prospect or for prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate" will be considered as corrupt practice, making the candidate liable for disqualification.

This provision would convince a person, unaware of the ground reality of Indian elections, that it is mandatory for candidates to shun reference to religion, race, caste and community in their campaign speeches. Despite the stringent law which threatens to disqualify a candidate on a single appeal to voters on the prohibited lines, caste and religious credentials of a candidate continue to be the key factor of her success in elections, depending on the demographic structure

of a constituency. Parties have sprung up on the foundation of caste and religion. Campaign speeches are getting shriller on caste and community lines.

A seven-judge bench of the SC in a 2017 judgment (Abhiram Singh vs C D Commachen) had further expanded the ambit of Section 123(3) to maintain purity of the electoral process. It brought within the ambit of corrupt practices “any appeal made to an elector by a candidate or his agent or by any other person with the consent of the candidate or his election agent to vote or refrain from voting for the furtherance of the prospects of election of that candidate or for prejudicially affecting the election of any candidate on the ground of religion, race, caste, community or language of (i) any candidate or (ii) his agent or (iii) any other person making the appeal with the consent of the candidate or (iv) elector”.

This means no candidate in Odisha can tell voters in the state not to vote for BJD on the ground that its leader and chief minister does not speak the local language fluently. Surprisingly, many who campaigned questioning Sonia Gandhi’s foreign origin and her religion and nationality did not fall foul of Section 123(3) in the last three general elections.

Congress candidates in the 2007 Gujarat assembly elections did not attract disqualification when Sonia threw the “dharm aur maut ka saudagar’ barb at then CM Narendra Modi. Congress candidates did not attract disqualification when the Congress president in April 2014 met the shahi imam of Jama Masjid Syed Ahmed Bukhari and sought his support. Bukhari appealed to Muslims to support Congress all over India. Similarly, an association of church leaders had issued an appeal to voters in 2014 asking them not to vote for BJP.

BJP leaders, Modi included, have never lost a chance to subtly mix religion in campaign speeches. The latest being Maneka Gandhi openly telling Muslims that consequences would follow if they did not vote for her.

Apart from religion being used by candidates to either seek votes or prejudice voters against their rivals, caste equations still continue to be a key parameter for a candidate’s success in polls. The stringent laws enacted by Parliament to prohibit the use of race, caste, religion and language of a candidate or electors during campaigning, and the Supreme Court’s attempt to sharpen the provisions by widening their ambit, has done little to deter candidates from using these very prohibited means to seek votes.

Scheduled caste (‘reserved’) seats in UP: the trend

Sub-caste challenge awaits BSP in reserved seats

TIMES NEWS NETWORK The Times of India

Lucknow: BSP may be rushing in to campaign for candidates in reserved constituencies in UP, but past experience shows that the party has performed poorly in these seats.

In 2009, BSP, which claims to be a party of dalits, was able to register a win in only two of the 17 reserved constituencies. Experts say the stumbling block is not only the uncertain transfer of Brahmin votes to dalit candidates but also that sub-castes within the scheduled castes (SCs) make it tough for the party to sail through.

While the BSP won Lalganj and Misrikh seats, its arch-rival, the Samajwadi Party (SP), won nine reserved seats, the Congres three and the BJP two. And the BSP has never won from reserved seats such as Nagina, Shahjahanpur, Hardoi, Basgaon, Mohanlalganj and Bulandshahr.

“Even this time, the Brahmin votes are unlikely to be transferred to the party,” said a district coordinator in a reserved constituency. “Since all parties put up SC candidates on these seats, the question of sub-castes in the SC category comes into play.”

C S Verma, a senior fellow at the Giri Institute of Development Studies in Lucknow, says that local-level politics come into effect in the reserved constituencies. “There’s a clear-cut fragmentation within the dalits.”

On the other hand, the BJP has the support of upper castes and some backward classes. Hence, the SP and the BJP score over the BSP in reserved constituencies.

Studies show out of 66 SCs, Chamars have the highest number, constituting 56.3% of the total SC population. Pasis happen to be the second largest group, forming 15.9% of the SC population. These two sub-castes combined with Dhobis, Koris and Valmikis constitute 87.5% of the total SC population.

While Chamars are concentrated in Azamgarh, Jaunpur, Agra, Bijnor, Saharanpur, Gorakhpur and Ghazipur districts, Pasis are is in Sitapur, followed by Rae Bareli, Hardoi and Allahabad. The other three major groups — Dhobi, Kori and Valmiki — have the maximum population in Bareilly, Sultanpur and Ghaziabad districts.

Conduct during elections: Model?

Legality of election-eve promises

The Times of India, Jul 20 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

Can parties be forced to fulfil promises made on eve of elections?

Political parties too issue manifestos prior to elections, promising many things. Politicians seek votes from citizens by telling them that if they are elected to power, their party will fulfill the election promises.

Tamil Nadu presents a good case study where arch-rivals DMK and AIADMK try to outdo each other with election-eve promises, which include free distribution of household items. For the 2006 assembly elec tions, the DMK's manifesto promised free distribution of colour TV sets to each household which did not possess the same, if it was elected to power.

DMK justified distribution of free colour TVs saying it provided commoners with recreation and general knowledge to housewives, especially those living in rural areas.DMK and its allies emerged victorious in the elections. To fulfill the poll promise, a policy decision was taken to provide one 14-inch CTV to all eligible families. To implement it in a phased manner, budgetary provision of Rs 750 crore was made.

For the 2011 assembly elections, the DMK again promised a raft of freebies if it returned to power. More than matching the DMK's promises, AIADMK too announced free gifts. It promised mixergrinders, electric fans, laptop computers, 4 grams of gold `thalis', Rs 50,000 cash for a girl's marriage, green houses, 20 kg of rice to all ration card holders, even to those above the poverty line, and free cattle and sheep.

The AIADMK and its allies swept the elections in 2011.Like DMK, it took steps to ful fill the promises.

S Subramaniam Balaji challenged the distribution of freebies by both parties, term ing it a corrupt practice to lure voters and also against right to equality as the free gifts were not meant for all voters.

The Supreme Court on July 5, 2013 decided Balaji's petition and ruled, “Promises in the election manifesto do not constitute corrupt practices under the prevailing law.“

However, it directed the Election Commission to frame guidelines for election manifestos and decide whether it could be included in the model code of conduct for the guidance of political parties and candidates.

“We are mindful of the fact that generally , political parties release their election manifesto before the announcement of election date, in that scenario, strictly speaking, the Election Commission will not have the authority to regulate any act which is done before the announcement of the date. Nevertheless, an exception can be made in this regard as the purpose of election manifesto is directly associated with the election process,“ the SC had said.

In the 2014 general elections, the Congress-led UPA was trounced by the BJP-led NDA after Narendra Modi succeeded in driving home the hope of “acche din aayenge“ (good days will come). The UPA regime was perceived so bad by the citizens that they lapped up the promise of “acche din“.

How can one quantify “acche din“? It is no colour TV or grinder-mixer that one can examine its quality . Good days for whom? And how will it come? If it comes, how long should the voter wait? And how long will it last? Election promises are a tricky affair. Citizens express their verdict on whether the promises were met only after five years. Is defeat at the elections just punishment for not meeting the promises? Lord Denning, sitting in the House of Lords, had in Bromley London Borough Council vs Greater London Council [1982 (1) All England Law Reports] elaborated on election promises.

“A manifesto issued by a political party -in order to get votes -is not to be taken as gospel. It is not to be regarded as a bond, signed, sealed and delivered. It may contain -and often does contain -promises or proposals that are quite unworkable or impossible of attainment. Very few of the electorate read the manifesto in full. A goodly number only know of it from what they read in the newspapers or hear on television. Many know nothing whatever of what it contains.

“When they come to the polling booth, none of them vote for the manifesto. Certainly not for every promise or proposal in it. Some may by influenced by one proposal. Others by another. Many are not influenced by it at all. They vote for a party and not for a manifesto,“ he had said.

As an advice to political parties successful in elections, Lord Denning had said, “When the party gets into power, it should consider any proposal or promise afresh -on its merits -without any feeling of being obliged to honour it or being committed to it. It should then consider what is best to do in the circumstances of the case and to do it if it is practicable and fair.“

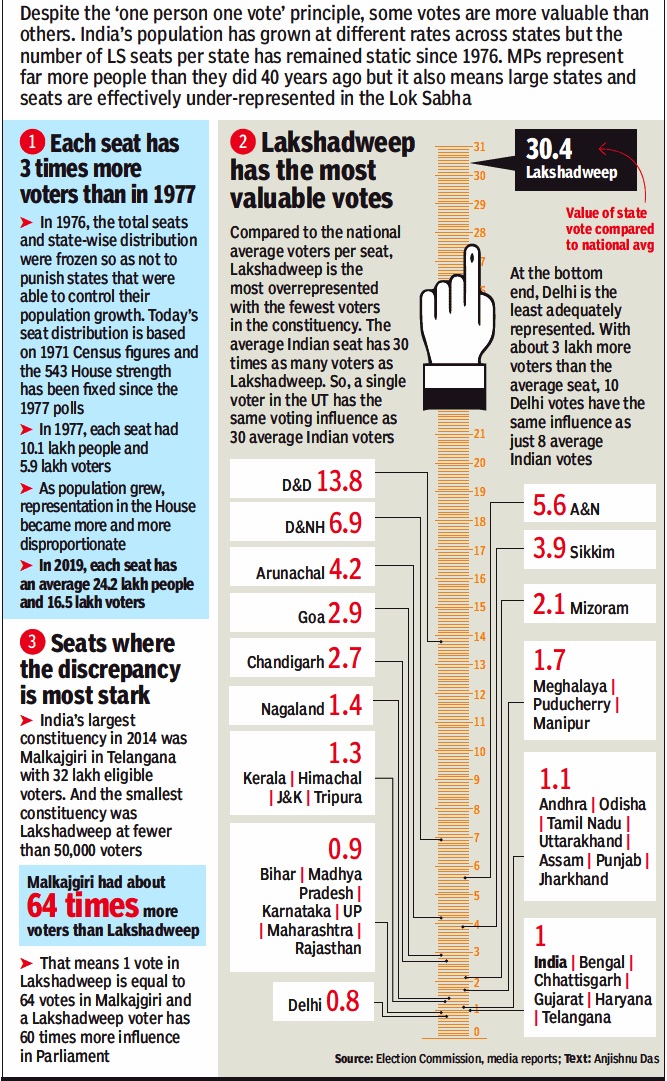

Constituencies: how many voters do they represent?

As in 2019

From: March 19, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

How many voters India’s parliamentary constituencies represent

As in 2024

April 10, 2024: The Times of India

From: April 10, 2024: The Times of India

Each vote counts in an election. But not all votes are equal. That is considering the fact that the number of voters is not the same for all Lok Sabha seats, though the understanding is that so far as practicable all seats should have about the same number of voters. The freezing of seats till 2026 (following the yet-to-be-held Census 2021) means that while it takes 21 lakh voters to elect an MP in the likes of Rajasthan and Delhi, the Lakshadweep MP has a constituency that’s only 58,000-strong — the smallest in India.

Corruption, corrupt candidates

Corruption does not bother the voter

Is graft really a big election issue? Stats say otherwise

Deeptiman Tiwary TNN

New Delhi: Is corruption really an issue in elections? Some surveys claim people worry more about the economy than corruption. Data for 2004 and 2009 general elections show that not only do parties continue to repeatedly field candidates facing graft charges, people even vote for them.

Analysis of affidavits filed by Lok Sabha candidates shows that in 2004, parties fielded a total of 12 candidates facing cases under Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA). Of them, nine won. In 2009, 15 candidates with PCA cases were in the fray with four emerging victorious. Both elections combined, 27 such candidates contested and 16 of them won — a success rate of almost 60%.

Data also shows only one of 2004’s winners (SP’s Rashid Masood) with graft cases lost in 2009. Of the nine winners in 2004, only three (including SAD’s Rattan Singh and RJD chief Lalu Prasad) contested in 2009. Among other winners of 2004, BSP chief Mayawati was UP CM at the time of the 2009 polls and SAD’s Sukhbir Singh Badal was Punjab deputy CM. One candidate died while others did not contest.

A recent survey by Lok Foundation and University of Pennsylvania’s Centre for Advanced Study of India says corruption has found some traction with voters this election, but is still at second position compared to economic growth.

Social and political theorist and Centre for the Study of Developing Societies professor Aditya Nigam says though people seemed to have accepted graft as a part of life until recently, this election could be different. “Giving bribes at every step for decades had made people accept corruption as their destiny. But the Anna Hazare-led anti-corruption movement and Arvind Kejriwal’s AAP have changed that feeling. Economic growth is too abstract an idea to attract masses unless someone breaks it down for them.”

Indeed, the perception is corrupt leaders can move things

April 28, 2018: The Times of India

‘The perception is corrupt netas can move things’

Set aside the grandstanding on cleaning up politics, the return of the Reddy brothers, to BJP in Karnataka has turned back the focus on the ‘winnability’ of corrupt netas. Political scientist and senior fellow at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Milan Vaishnav talks to Jayanth Kodnani about the “perplexing cohabitation” of criminality and democratic politics as discussed in his recent book on why parties field the corrupt and why voters elect them, When Crime Pays. Extracts from the interview

Your study shows the tribe of corrupt netas in the poll arena is growing. What explains this

• The reason is two-fold. First, parties are desperate to identify wealthy, selffinancing candidates. Those involved in criminal activity have both the ability and incentives to deploy resources to winning electoral office. From the voters’ perspective, candidates often use their criminality to signal their credibility... There is the perception that tainted politicians “know how to get things done”.

Do voters elect them in spite of knowing their criminal bona fides?

• Research demonstrates that voters are wellaware of the details of candidates they support. Perversely, they vote such candidates because of, not despite, their criminality. A politician with criminal background manages to create an aura of a “godfather”.

Does the seriousness of criminal charge make a difference in choice of candidates — say, between a white collar crime and one of murder?

• The dominant strain in the data is ‘blue collar’ crime, for lack of a better word. These are politicians associated with physical acts of abuse and/or throwing their weight around. While it is true that a large number of politicians are suspected of white -collar offences, politicians exclusively linked with white-collar crimes do not enjoy the same level of popular support, in my view. People ask: what’s in it for me?

Do tainted politicians use additional identity groupings (caste, region or sect) for ‘dabangg’ influence?

• Caste and identity are inextricably tied to the dabangg image. Almost all strongmen mobilise their social identity (caste or religion). This allows them to slice and dice the electorate in their favour, at the same time establishing their bona fides with supporters with whom they share fundamental affinity. The politician’s criminality is then cast in terms of protecting the status of his or her community as a defensive. It reinforces the idea of a Robin Hood narrative.

Is abusive trolling online muscle flexing?

• It’s a way of asserting presence, much like advertising. The difference is the degree of individual and group targeting, which can be very sophisticated. It is a way for politicians to assert their viability and demonstrate their credibility.

Expenditures

Gujarat, 2017

TNN, Nov 15, 2022: The Times of India

AHMEDABAD: Politicians can indeed exceed expectations when it comes to spending money on voters, splurging 1,000% higher than promised. But that applies only to campaigning, before the netas are elected. A study has shown that in the 2017 Gujarat election, candidates burnt Rs 459 per voter in outreach programmes when the Election Commission of India (ECI) cap implied that approximately Rs 45 per voter could be spent. The figures have been derived using the overall limit of Rs 28 lakh per candidate set by the ECI for campaign expenses in 2017.

The study of poll expenses was the first of its kind and involved researchers from Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, and from two American institutions, Temple University in Philadelphia and Vanderbilt University in Nashville. The researchers scrutinised expenses incurred by candidates in the previous assembly election in a Walled City constituency in Ahmedabad, and in Kapadvanj.

The study analysed poll spending between November 2017 and March 2018. The researchers noted that in Ahmedabad, the Congress candidate had shown expenditure of Rs 13.4 lakh, the BJP candidate had declared Rs 10.5 lakh, while an Independent candidate had reported Rs 2.7 lakh. In Kapadvanj, dominated by dairy cooperatives and rural voters, the Congress candidate submitted expenses of Rs 9.7 lakh and the BJP candidate of Rs 11.8 lakh.

Researchers Ashwani Kumar of TISS, Souradeep Banerjee of Temple University, and Shashwat Dhar of Vanderbilt University collated expenses that candidates of both the major parties had incurred in Ahmedabad and Kapadvanj in 14 days before polling. The researchers found that the candidates had spent Rs 16 lakh to Rs 28 lakh each on organising sabhas and rallies, Rs 7 lakh to Rs 14 lakh for allowances for booth managers, and about Rs 10 lakh for printing banners.

The researchers determined that the candidates had spent overall between Rs 57 lakh and Rs 1.2 crore.

But how do parties and candidates bypass the official ceiling and underreport aggregate election expenses? The study found that third-party accounts are used to pump money into campaigning. These accounts typically belong to family members and aides of candidates.

For the 2022 poll, the ECI is expected to spend Rs 450 crore, which works out to Rs 90 per eligible voter, to get the voter to the booth. The state has 4.6 crore voters this year.

"Candidates receive an amount to the tune of Rs 50 lakh to Rs 60 lakh from party coffers," the study said. "Small businesses and traders' associations are major sources of candidate funding," the study said. "Real estate, cement and the construction sectors are among the biggest political donors."

Pankti Jog, state coordinator of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), said: "There is no effective mechanism to control the use of money during elections."

‘Inauspicious’ periods

Holashtak days of March

Two days after nominations for the first phase of the 2019 Lok Sabha polls began, not a single candidate from any of the main political parties has filed his papers here. The chief reason: Holashtak, or a period of eight days preceding Holi that is considered to be highly inauspicious. In 2019, Holashtak began on March 14 and will end on March 21, when the Holika fire is lit.

It is believed that during the period of Holashtak, a host of heavenly bodies, along with the feared astrological quantity called Rahu, undergo transformations that make it inadvisable to hold auspicious ceremonies during this time.

Said BJP’s former state president Laxmikant Bajpai, “A Hindu contestant will not file his nomination before the culmination of Holashtak as any work done during this period becomes counter-productive.”

Somesh Kumar, additional district election officer in Meerut, said, “Nomination forms start coming in from the second day, but no form was filed here on Tuesday. Some of them are delaying it for religious reasons.”

According to astrologer Ashwini Tripathi, “During the Holashtak period, cosmic changes take place that minimise the intensity of rays of the Sun, which is the main provider of energy to Earth. Because of this, the period is considered inauspicious.”

Indira Bhati, the Congress candidate from Bijnor, cited Holashtak for delaying the filing of her nomination. “I will file my papers after Holi when the time is auspicious.”

Indelible ink

Quantities ordered: 2009-19

April 13, 2019: The Times of India

From: April 13, 2019: The Times of India

Trinamool candidate Mimi trolled for gloved handshake

Bengal’s actor-turned-politician Mimi Chakraborty was trolled on Friday as a photo of her wearing gloves and shaking hands with people went viral on Friday. Mimi said she had applied some ointment to heal scratches and burns sustained over the past few weeks and had covered her hands to ensure the medicine did not smudge. “The photo was taken when I was returning home in my car from a rally at Sonarpur on Thursday,” she said. “While resting in the car after applying medicine, I found some fans waiting by the roadside and lowered the window to respond to their greetings. The handshake was not part of my campaign. I am astounded at how low the BJP IT cell is stooping,” she said.

Betul candidate files papers first for luck, then for show

Durga Das Uike, the BJP candidate from Betul in MP, will file his nomination twice. On April 10, the schoolteacher and R S S leader filed his papers as the stars were aligned and it was an ‘auspicious time’ for him. On April 15, he will file his papers again for the May 6 polls, this time in the presence of former CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan, with pomp and show. “On April 10, I had just done a formality because, according to priests, the ‘subh muhurat’ for me was between 1pm and 1.30pm that day.” Filing multiple nomination forms is common, but most do it to ensure that if one nomination is rejected due to a technical error, there is another.

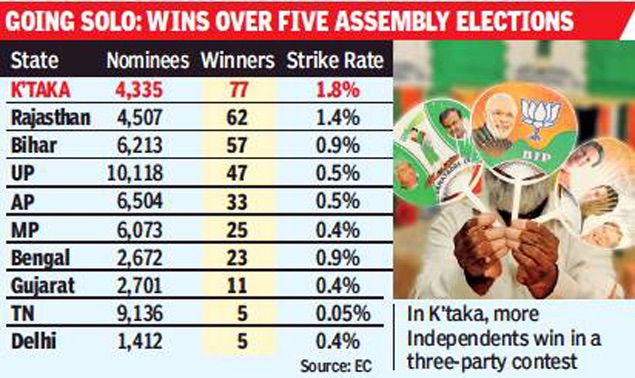

Independent candidates

1957-2014: electoral performance

Independent candidates haven’t fared well since the early elections. The highest number of independent winners was recorded in 1957, when 42 of the 481 such candidates were elected. It’s only been downhill from there. Though the number of independents contesting has risen steadily, peaking at 10,635 in 1996, a vast majority not only loses but also forfeits deposits by failing to capture one-sixth of the total votes polled. In the 2014 Lok Sabha polls, a total of 3,234 independents contested, but only three won and a whopping 3,218 lost their deposits

More Independents win in Karnataka than other big states

Chethan Kumar, April 28, 2018: The Times of India

The years when the five elections counted took place have not been mentioned, but the time span could be assumed as roughly 1990- 2015

From: Chethan Kumar, April 28, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Results of 50 elections show that nearly 2% of Independents in Karnataka stand a good chance of winning.

Barring Rajasthan, no other state has offered more than 1% chance of winning.

One factor that ups their winnability is the fact they are rebel candidates, says analyst Harish Ramaswamy.

Disgruntled individuals across parties have sworn to defeat their parties’ official candidates after being denied tickets ahead of the May 12 assembly election in Karnataka.

While some have already joined rivals, others are likely to contest as Independents, with potential to cause upsets across the state. Over the past five elections, Independent nominees in the state have had a better chance at winning than similar candidates in 10 major states.

Results of 50 elections — five each in Karnataka, Andhra, Tamil Nadu, UP, Gujarat, New Delhi, Bihar, Rajasthan, Bengal and MP — show that nearly 2% of Independents in Karnataka stand a good chance of winning. Barring Rajasthan, no other state has offered more than 1% chance of winning.

One factor that ups their winnability is the fact they are rebel candidates, says analyst Harish Ramaswamy. For example, Belur Gopalakrishna, denied a ticket by BJP in Sagar, has said not only would he not back Hartal Halappa (who got the ticket), but would doubly ensure BJP is routed.

“Independents who make a difference are confident people who believe they have nurtured the constituencies. When they rebel and contest, they also take away a good portion of the party’s machinery,” Ramaswamy said.

The trend of Independents winning here started in 1983 when 22 such candidates won, says analyst S Mahadevprakash. Strong local leaders, especially at zilla panchayat levels, with about 30,000 to 40,000 votes under their influence can trigger upsets. “This happens every time there is a three-party fight. Local leaders snatch votes when the mandate is already fractured,” he says. UP’s seen the highest number of Independents contesting in the past five elections.

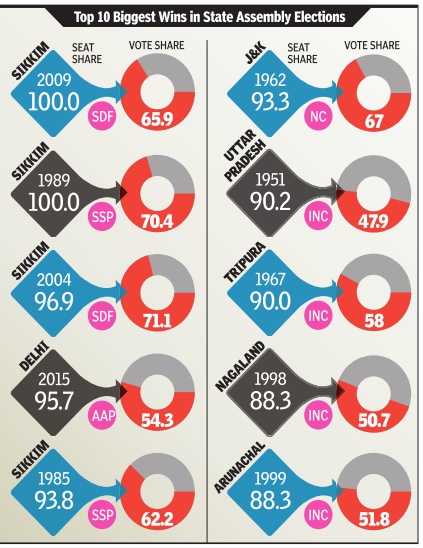

Landslides: Major electoral landslides

1951-2015

The Times of India Feb 12 2015

AAP's tally of 67 out of 70 seats in Delhi means it won about 96% of the total seats in the state assembly. An analysis of over 300 assembly elections held since Independence shows that the battle for Delhi was among one of the most one-sided ever. In terms of the proportion of total seats won by the largest party, AAP's sweep is the fourth largest so far. The previous three have all been in Sikkim. The Sikkim Sangram Parishad led by Nar Bahadur Bhandari won all 32 seats in 1989, the first instance of a 100% sweep. In 2009, the Sikkim Democratic Front led by Pawan Kumar Chamling repeated the feat. The SDF had in 2004 come close, winning 31 of the 32 seats

Length of polling process

1951-52

From: March 11, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The length of the polling process in 1951-52

Why Indian elections have stretch for weeks since the 1990s

SA Aiyar, In Digital India, why do elections stretch for weeks?, March 10, 2019: The Times of India

In most democracies, polling occurs on a single day, and the counting of votes begins soon after polling ends. In the US, counting of votes in East Coast states can start before polling ends in West Coast states, which are in a time zone three hours behind the east. Typically, counting begins and election results are declared the same evening or next day.

But India takes ages to hold a poll, and the time between the first and last rounds of polling keeps rising. In the 2004 general election, polling in four phases took 21 days. In 2009, polling over five phases took 28 days. Polling in the 2014 election required no less than nine phases over 37 days.

Is India too large to organise elections in a day or two? No, even elections in a single state take weeks. The 2015 Bihar election was held in five phases over 24 days. The 2017 election in Uttar Pradesh required seven rounds of polling over 26 days.

Moreover, we have long gaps between the last day of polling and counting of votes. In the 2014 election, counting started three days after polling ended. A task taking a few hours in other democracies takes three days in India. This is not because of manual counting, as was the case in earlier decades. In recent times, all votes are recorded on electronic voting machines. But these are not digitally interlinked, and after polling, are kept in secure storage, with all political parties keeping guard, to check against hanky-panky. They are eventually all moved to counting centres.

Why does holding elections and counting votes take so long? In the early decades after Independence, polling was held mostly on a single day, with no violence. The main exception was in snow-bound areas like Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, where elections took place later. By the 1960s, violent political clashes at election time caused many deaths. By the 1980s, the capture of polling booths and stuffing of ballot boxes by gangsters of sundry parties became a menace. The police and para-military forces were supposed to check this. But often the ruling party facilitated booth capture by its own goons, who were aided by manipulating deployment of security forces. Democracy was in jeopardy.

Chief election commissioner T N Seshan finally checked this in the early 1990s. He berated chief ministers and other politicians for booth capturing. He decided that the Election Commission and not chief ministers would control the deployment of security forces to ensure fair elections. He phased polling over several days so that security forces could be shifted from one polling zone to another. In time, this mostly ended booth capture by gangs. When officials or rival parties reported a capture, repolling would be ordered, making booth capture a failure.

1952-2014: votes received by the winning party

From: March 14, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

1952-2014: votes received by the winning party

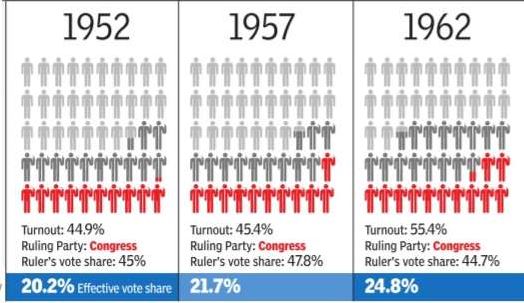

Mandate: the representativeness of political parties

The mandate for the ruling party/ coalition: Its size 1952-2014

From: Nov 25, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Mandate: the representativeness of the national ruling party/ coalition, 1951-2019

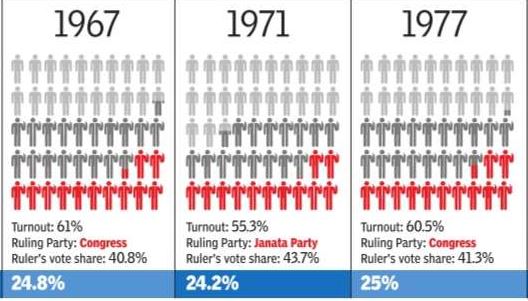

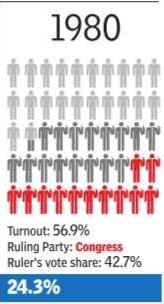

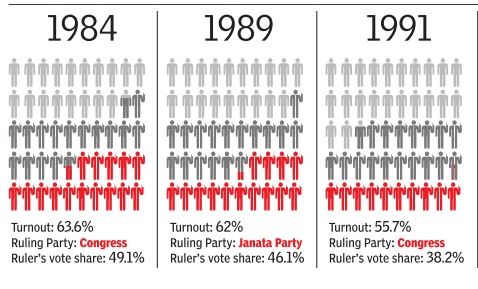

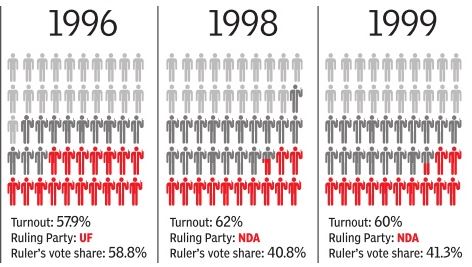

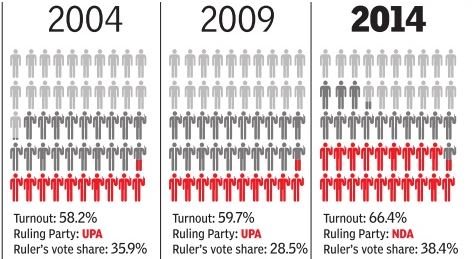

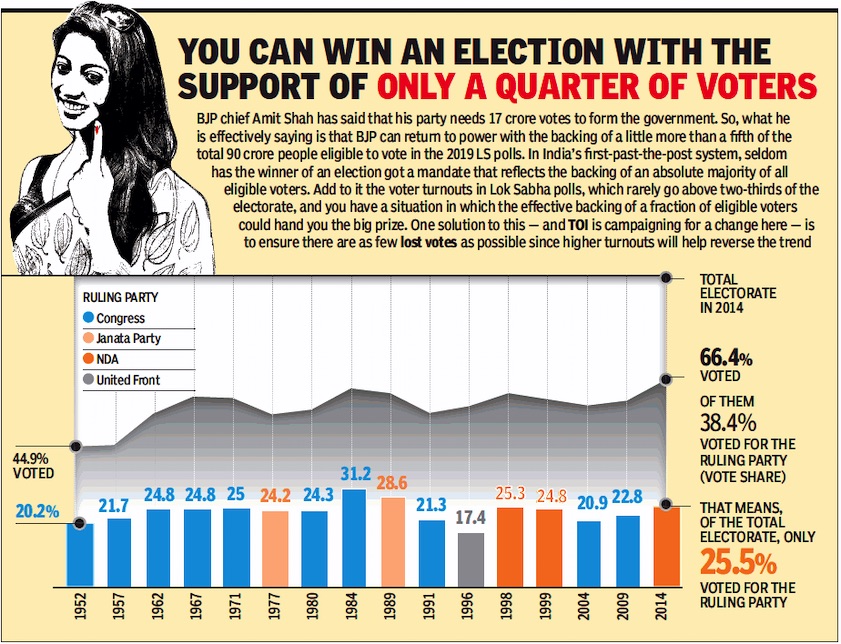

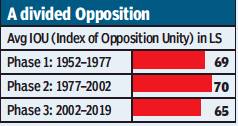

VOTE A MANDATE

The Times of India May 17 2014

When many choose not to vote and only a fraction of those who do opt for the ruling party, those in power could have a `mandate' that involves a really small proportion of all those eligible to vote. As the polity has fragmented, the `effective vote share' for the ruling party or coalition has shrunk.

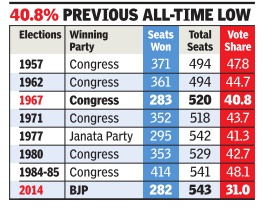

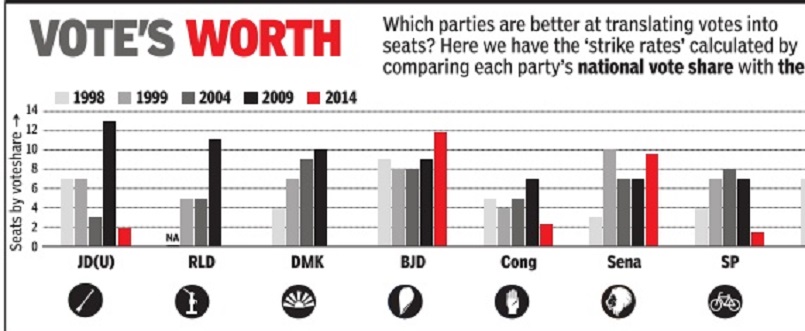

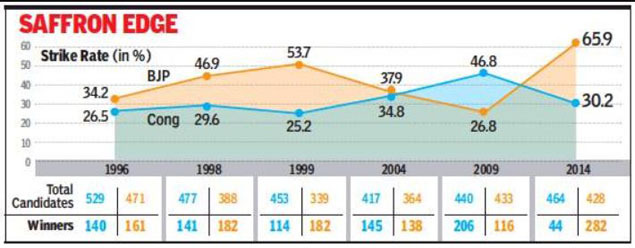

BJP's 31% lowest vote share of any party to secure majority

The Times of India May 19 2014

TIMES INSIGHT GROUP

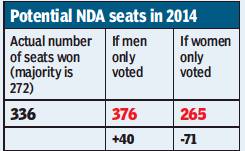

The fact that BJP has won a majority on its own in the 16th Lok Sabha has, inevitably, drawn comparisons with previous polls in which parties won a majority on their own. (Chart1: The vote share of the winning party; Chart 2: Strike rate)

What has not quite figured in most of these comparisons is the fact that no party has ever before won more than half the seats with a vote share of just 31%. Indeed, the previous lowest vote share for a single-party majority was in 1967, when Congres won 283 out of 520 seats with 40.8% of total valid votes polled.

Far from spelling the end of a fractured polity, the 2014 Lok Sabha poll results show just how fragmented the vote is. It is precisely because the vote is so fragmented that the BJP was able to win 282 seats with just 31% of the votes. Simply put, less than four out of every 10 voters opted for NDA candidates and not even one in three chose somebody from the BJP to represent them.

Those who picked Congres or its allies were even fewer, less than one in five for Congres with a 19.3% vote share (which incidentally is higher than BJP's 18.5% in 2009) and less than one in every four for the UPA. Unfortunately for Congres, its 19.3% votes only translated into 44 seats while BJP's 18.5% had fetched it 116 seats.

With the combined vote share of the BJP and Congres -the two major national parties -adding up to just over 50%, almost half of all those who voted in these elections voted for some other party . Even if we add up the vote tallies of the allies of these two parties, it still leav es a very large chunk out.

The NDA's combined vote share was 38.5% and the UPA's was just under 23%. That leaves out nearly 39% -or a chunk roughly equal to the NDA's -for all others.

Is the 38.5% vote share for the NDA the lowest any ruling coalition has ever obtained? Not quite. The parties that constituted UPA-1 had just 35.9% of votes polled and the Congres won just 38.2% of the votes in 1991, when it ran a minority government under P V Narasimha Rao. But, except in 1991, they had to depend on outside support to keep the government afloat, which meant that the total vote share of those in the government or supporting it was higher.

In 1989, the National Front, consisting of the Janata Dal, DMK, TDP and Congres (S) won 146 seats and a vote share of 23.8%. To this were added the 85 seats and 11.4% of BJP and the 52 seats and 10.2% of the Left, taking the total, including those parties supporting from outside, to 283 seats and 45.3% of the votes.

In 2004, parties in the prepoll alliance stitched up by Congres had 220 seats and just under 36% of the votes. But the UPA then got outside support from the Left, SP and PDP, which between them had 100 seats and about 11.2% vote share. Thus, UPA-1 was formed with the support of 320 MPs and about 47% of votes.

The NDA does not need any outside support to form the government. Indeed, BJP can form it even on its own. But unless it ropes in others, the party will become the government with the lowest popular support in terms of vote share after the Rao government.

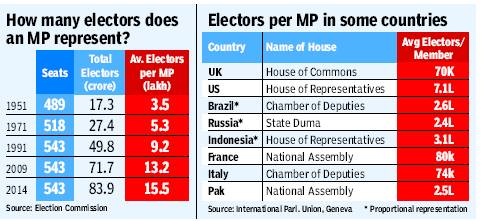

One MP for 16,00,000 voters

Mind the gap: 1 MP for 16L voters

Keeping In Touch With Electors Tough

Subodh Varma | TIG The Times of India

For the 2014 general elections, over 84 crore/ 840 million people are registered as voters as per the latest Election Commission figures. They will elect 543 MPs. That means on average, each MP represents over 15.5 lakh voters. That’s almost four and a half times the number of voters per MP in the first general elections held in 1951-52.

Voters have been increasing because population is increasing. But the number of seats in Lok Sabha has not increased since 1977. As a result, an MP has to represent more and more people with each passing election.

This anomaly gets stranger if you look at statewise averages of voters per MP. For the coming election, a Rajasthan MP will represent nearly 18 lakh voters on average, while one from Kerala will represent just 12 lakh voters. This is among the bigger states, not counting the smaller states and UTs where MPs can get elected with as low an electorate as 50,000 as in Lakshadweep or four to eight lakh in the Northeast.

In the 2008 delimitation, standardization of constituencies did not take place as it would have meant creating more constituencies in states like Rajasthan or Bihar with higher population growth rates, and cutting down in states like Tamil Nadu or Kerala with lower population growth, says election expert Sanjay Kumar, director of New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Studies of Developing Societies.

“It would have meant penalizing states that have successfully restricted their population. This was not fair,” he explained.

So, constituency numbers were kept the same within states, leading to the present anomalous ratio of voters per MP. Nowhere in the world is there such a high ratio of voters per elected representative. The closest would be the US where the average number of voters per House of Representatives member is about 7 lakh.

All this leads to an increasing disconnect between people and elected representatives, turning serious as elections approach. In two weeks candidates have to somehow contact 15 lakh people. With increasing restrictions on overt spending – on posters, vehicles or public meetings – the dynamic of contesting elections is fast changing. And so is covert spending. Increasing use of electronic media or Web-based platforms is also driven by this compulsion.

Once the MP is elected, the responsibility of staying in touch with the voters also is more difficult.

Although the MP is not supposed to be looking after day-to-day issues like roads or drinking water or whether doctors are there in health centres, in India’s topsy turvy democracy it doesn’t work like that.

“People expect their elected representatives to solve everything. They don’t make a distinction between what an MP is responsible for and what a local councillor is supposed to do,” says Kumar.

In reality, the elected representatives too don’t follow these distinctions when it comes to promises, so the people can’t be blamed.

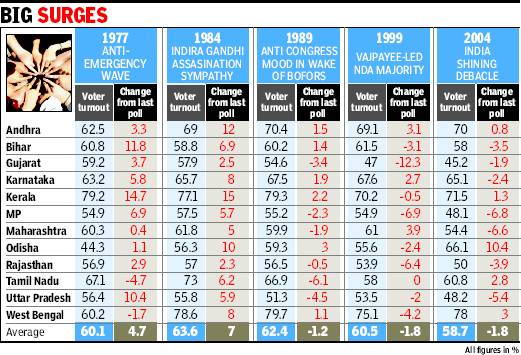

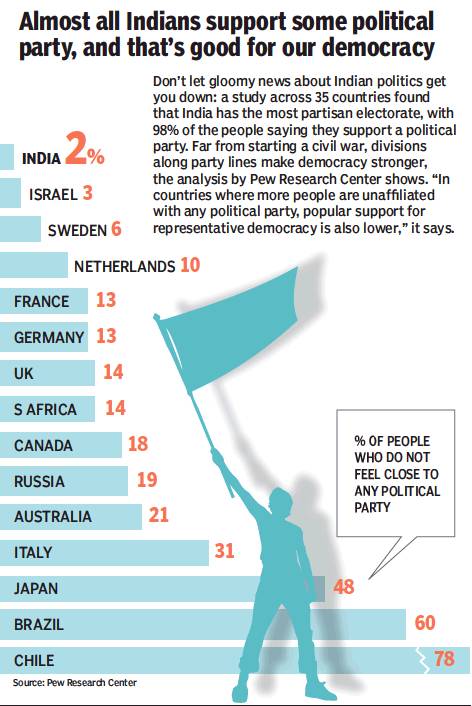

So, what is the solution? In the future, there is no option but to increase the number of seats in the Parliament opines Kumar. But for now, the unwieldy electoral system will have to bumble along.