Coastline, beaches: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Beaches

Blue Flag’ certification

2020

Vishwa Mohan, October 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, October 12, 2020: The Times of India

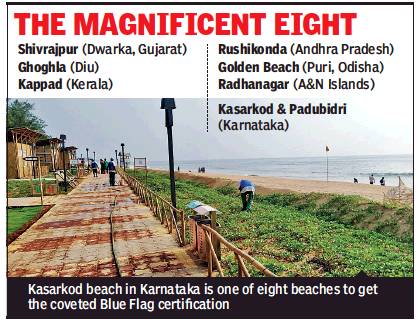

Eight Indian beaches have got the coveted ‘Blue Flag’ certification — an international ecolevel tag which is one of the world’s most recognised awards for clean, safe and environment-friendly beaches, marinas and sustainable boating tourism operators.

The beaches which have got the tag are Shivrajpur (Dwarka, Gujarat), Ghoghla (Diu), Kasarkod and Padubidri (Karnataka), Kappad (Kerala), Rushikonda (Andhra Pradesh), Golden Beach (Puri, Odisha) and Radhanagar (Andaman & Nicobar Islands).

Blue Flag beaches are considered the world’s cleanest beaches. In order to qualify, 33 stringent criteria relating to environmental, bathing water quality, educational, safety, services and accessibility standards must be met by the beaches.

“It is an outstanding feat considering that no ‘Blue Flag’ nation has ever been awarded for eight beaches in a single attempt,” said Union environment minister Prakash Javadekar while announcing the decision of the international jury. He said, “This is also a global recognition of India’s conservation and sustainable development efforts… India is also the first country in the Asia-Pacific region which has achieved this feat in just about two years’ time.”

Union environment ministry had last month sent the list of these eight beaches to the international jury, seeking Blue Flag certification which is accorded by the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE), headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark. The jury, which takes a final call on this certification, comprises eminent members from the UN Environment Programme, World Tourism Organisation, FEE and IUCN.

Over 4,600 beaches, marinas and boats from around 50 countries have, so far, got the Blue Flag certification. Spain has the highest number of Blue Flag tagged sites. India, which started working on getting the tag in 2018, has plans to expand the network of Blue Flag certification to 100 such beaches in the country in the next five years.

In order to achieve this goal, the environment ministry had last month launched India’s own eco-label “BEAMS” (Beach Environment & Aesthetics Management Services) under its Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) project. Besides the Blue Flag tag for its eight beaches, India has also been awarded a third prize by the jury under the “International Best Practices” for pollution control in coastal regions. The certification is considered important for tourism as this tag attracts both domestic and international tourists to these beaches.

Odisha, As in 2019

Ashis Senapati, Sep 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ashis Senapati, Sep 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ashis Senapati, Sep 6, 2019: The Times of India

Wading through mulchy sand in Barahapur village in Odisha, Jagannath Behera comes to an abrupt halt and points to ruins of abandoned and partially submerged houses. “That’s where my land used to be. Thirty years ago, the sea was far away. But every year, it is getting closer,” the 60-year-old said, adding that rising sea levels started to sink their hamlet in the 1990s and, before long, had swallowed several homes and farmlands.

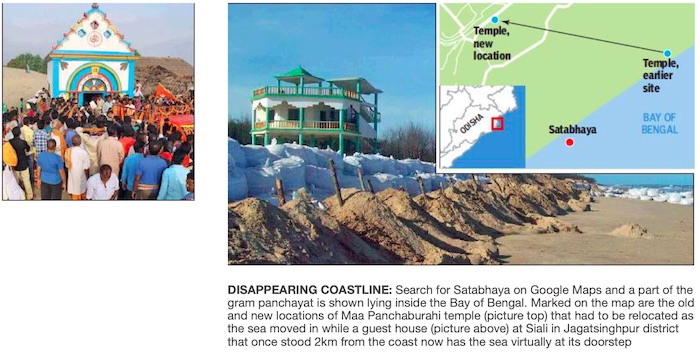

Barahapur is not an exception. Sea erosion is destroying many coastal towns in Odisha. In Satabhaya gram panchayat alone, where Barahapur village is located, 3,000 people have been evacuated to safer areas in the past two decades. A quick look at Google Maps shows a part of Satabhaya gram panchayat in the sea. What it doesn’t show is that there are still several people living a precarious life on the edge of the coast.

Odisha’s coast — home to the largest-known nesting site of the Olive Ridley sea turtle and also Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon — is losing several metres of coastline every year. Between 1990 and 2016, Odisha lost 28% of its 550-km coastline, according to a 2018 study by the National Centre for Coastal Research, Chennai. Two of the six coastal districts of the state bore the brunt — Kendrapada and Jagatsinghpur, respectively, lost 31 km and 14.5 km of their coastline during the study period, resulting in thousands being displaced.

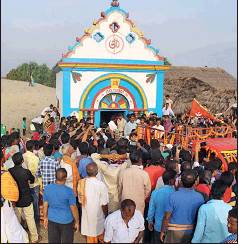

Among these environmental refugees is a local deity — Maa Panchaburahi — who was shifted to a new temple in Bagapatia, 10 km away, along with 571 residents of Satabhaya gram panchayat who were rehabilitated by the government between 2008 and 2017. About 120 families still remain in the panchayat area, fighting a losing battle against the sea.

Drinking water is fast becoming scarce as the sea has come dangerously close to two tube wells in Satabhaya. One of the tube wells that initially stood one metre above the ground now towers at six metres as the land around has eroded. Locals have to use a rope to draw water from it. “The other tube well was lost to sand two months ago,” said Janaki Lenka. Around the same time, a tidal surge washed away her home. But her family is reluctant to move. Prafulla, Janaki’s husband, who owns 20 buffaloes and earns his living by delivering milk, said the rehabilitation site in Bagapatia has no fields where his cattle can graze. “I make Rs 10,000 every month selling buffalo milk to the government-run milk federation. If there are no grazing pastures for my animals, I can’t move.”

A dangerous mix of rising sea levels due to climate change, felling of mangrove forests for construction and infrastructure-building too close to the sea is leading to erosion. Kakani Nageswar Rao, emeritus professor in the department of geo-engineering at Andhra University said that until the 1960s, the area of the Satabhaya gram panchayat was covered with dense mangrove forests. “To build the port at Paradip, the government cleared acres of mangrove forests. Then to protect the port from the onslaught of the sea, the government built a sea wall. As a result, the waters moved towards Satabhaya,” explained Rao.

A number of mighty rivers enter the Bay of Bengal on the east coast, bringing with them silt and leading to accretion (sedimentation) along the coast. The east coast, over time, was shaped by a balance of accretion and erosion. However, largescale construction of dams in the 1960s decreased the amount of silt being carried by these rivers to the river mouth. With a decrease in sedimentation, the rates of erosion went up. Cyclones also played a part, eating into the landmass faster and many believe the Super Cyclone in 1999 spelt the end of Satabhaya.

Authorities in Odisha said they have taken various measures to counter the threat. A 600m-long geo-synthetic sea wall was built in Kendrapada’s Pentha village three years ago to minimise sea erosion due to high tides. Plans are afoot to quickly rehabilitate the remaining families in Satabhaya, said Kendrapada collector Samarth Verma.

Kanhu Charan Dhir, additional district magistrate of Jagatsinghpur’s Paradip municipal town, said a wall is planned in Siali village in the district where a government guest house built 2km from the sea over a decade ago is now touching the waters.

Significance

Ashis Senapati, Oct 7, 2019: The Times of India

WHY ODISHA'S COAST IS IMPORTANT

Asia's largest brackish water lagoon located along state's coast

World's largest-known nesting site of Olive Ridley turtles located along state's coast

Bhitarkanika, the subcontinent's second-largest mangrove formation, after the Sundarbans is located on the coast

Indian coastline under threat

The Times of India, Aug 05 2015

Subodh Varma

Cash-strapped authorities put coastline under threat

Construction, erosion top worries: Panel

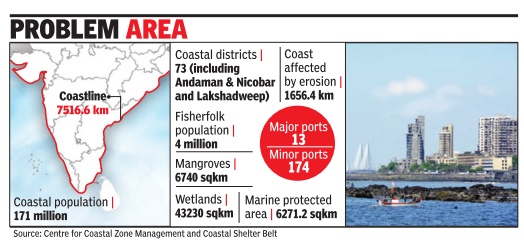

India's 7500 km long coast line, home to over 171 mil lion people, is under threat and the government machinery meant to manage it is in disarray . The coastal zone management authorities (CZMA 's) at the national and state level are orphaned bodies with no financial support, except what they raise by charging fees from those wanting project clearance. They are packed with ex-officio bureaucrats from various departments with limited expertise.Their meetings are spent in discussing project applications. They clear 80% of projects but never go back to monitor or check violations. They don't have maps with requisite details. They have not even marked out the high tide line.

These are the shocking findings of a report prepared by a group of environmental activists cum experts from the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi and the Namati Environmental Justice Program. The authors interviewed sitting and ex-members of the CZMAs, analysed minutes of 350 meetings of the CZMAs and looked at high court and National Green Tribunal cases over the years.

By a 1991 government notification, the coast is divided into four zones -one stretches over the water while three stretch landwards going up to 500 meters from high tide level. Multiple, contesting us es are vying for a piece of the coastindustries, real estate, tourism, livelihoods, mining and conservation, says Meenakshi Kapoor, one of the researchers.

“There are threats from unregulated construction, discharge of untreated effluents and sewage, destruction of mangroves, deterioration of critical ecosystems such as estuaries, saltpans, coral reefs, etc and coastal erosion,“ she said.

In most coastal Indian cities, poorer sections are forced to live in slums on the coast. Municipal authorities allow destruction of natural drainage and wetlands, as in Mumbai, causing flooding.Over 90% of sewage pouring into the sea from 87 big cities is untreated.

It was to regulate and monitor these threats that the coastal zones were notified and CZMAs were set up. On paper there are strict rules about where you can build a hotel or an ice factory , and where you can have fish processing units or net mending yards. And, the CZMAs are supposed to keep a tight watch. But the reality is reverse.

The report narrates in harrowing detail their analysis of 350 meeting minutes of national and state CZMAs. The NCZMA discussed 157 agenda items between 2003 and 2013 of which 73 related to reclassifying a piece of the coast so that it can be used differently . Just 12 cases of violations and just one case of reviewing what the state CZMAs were doing was discussed.

The state CZMAs were initially given Rs 5 lakh each by the central environment ministry . After that they have been left to their own de vices till 2011 when state governments were asked to fund them. Meanwhile each state CZMA has hammered out its own way of raising funds.

In Goa, if you want to set up a commercial institution, you apply to the Goa CZMA and pay Rs 10,000 fees. For setting up anything worth upto Rs 5 crore, you pay processing fees of Rs 25,000 in Gujarat, Rs 1 lakh in Maharashtra or just Rs 10,000 in West Bengal. Since the money is coming from project proposals, maximum time is spent by the state bodies discussing them. In Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Odisha, over 90% of the agenda items were project proposals.

In other states, this frequency was between 60 to 80%, with only Goa having 46% frequency , according to analysis of meeting minutes between 2010 and 2013.

The report recommends an overhaul with better definition of roles and powers, more resources, participatory planning, bringing in transparency , and improving monitoring and compliance. Otherwise, this bureaucratic mess will be unable to save India's coasts.

Soil erosion

Ashis Senapati, May 23, 2021: The Times of India

COASTLINES LOST DUE TO SOIL EROSION

Almost one-third of India’s 6,632km coastline was lost to soil erosion between 1990 and 2016

In the past three decades, east coast was the worst affected due to cyclonic activities from Bay of Bengal

West Bengal (63%), Puducherry (57%), Kerala (45%), Tamil Nadu (41%) most suspectible to erosion

Source: National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along Indian coast