Sons of the soil/ local job-seekers: 'reservations'/ quotas for: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Why such quotas fail

1995-2018

Why MP’s promise of 70% jobs to locals will fail, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Why MP’s promise of 70% jobs to locals will fail, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2019: The Times of India

(With reports from Rajendra Sharma in Bhopal, Kapil Dave and Melvyn Thomas in Ahmedabad, Bhavika Jain in Mumbai, Sandeep Moudgal in Bengaluru, B Sivakumar in Chennai)

Kamal Nath’s plans ignore enforcement hassles faced elsewhere

The Kamal Nath-led Congress government in Madhya Pradesh announced 70% reservation for locals in industries shortly after taking office. Across the country, such quotas have been introduced from time to time, but they have mostly remained on paper, mainly due to the reluctance of industries to carry out the policy and also because of an absence of enforcement mechanisms on the part of state governments.

In the past, industries have been hesitant — and understandably so — to dilute their hiring standards to meet a state’s job quota criteria. Chief minister Kamal Nath will have to do a delicate balancing act to ensure that investors still find it lucrative to do business in MP while meeting the quota criteria. During the previous BJP rule of 15 years, similar hurdles had compelled the full-majority government to bend norms to the demands of industries -- the 50% job promise remaining on paper. Still, investment didn’t flow.

“I personally welcome the provision for quota. We tried to implement 50% quota during our government but did not enforce it as a part of our industrial policy to bring investments. There were some hurdles related to skilled and technical manpower,” former state finance minister Jayant Malaiya told TOI.

Most industrialists suggest that those seeking jobs must have passed at least Class XII, but the quality of job-seekers is a problem. “We are aware of the standard of education in MP. There is an urgent need to improve it,” said higher education minister Jeetu Patwari.

Maharashtra in 2008 introduced 80% reservation for locals in industries that seek state incentives and tax subsidies. For industries that do not take incentives, this is still an indicative law.

Officials from the industries department of the state did not share data for the number of jobs created and those held by locals, but said the reservation policy didn’t take off.

According to them, there is no mechanism to check whether the stipulated quota of locals has been recruited. “We only check the number of employees from the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) accounts that a company opens. There is no way to find out how many of them are locals or from other states,” said a senior official.

He added that sometimes companies have been forced to hire ‘outsiders’ because of the lack of skill sets among local applicants for a particular job. “For sectors like chemical technology, textile and bio-technology, local employees are hard to find,” he explained.

The Gujarat story is no different. It introduced 85% reservation for locals as far back as 1995. The policy was never enforced, either in the private or public sectors. A significant number of workers in the ceramic, construction, textile, diamond and services sector come from Bihar, UP, West Bengal, Odisha and elsewhere.

Labour and employment minister Dilip Thakor said, “The idea of bringing a legislation for reserving jobs for locals was dropped as it was legally challenging and not implemented anywhere in India.”

In Karnataka, the government on December 2016 had planned to provide Kannadigas 100% reservation in mainly bluecollar jobs in private sector industries, except infotech and biotech. Early in 2018, the law department vetoed the idea on legal grounds, referring to articles 14 (right to equality) and article 16 (right to equal opportunity).

Later in January 2018, then advocate general (AG) Madhusudan R Naik said the government could suggest to the private sector to give “preference” to Kannadigas but could not force it to fall in line. The matter has not been raised since.

Meanwhile, MC Sampath, industries minister of Tamil Nadu, another highly industrialised state, had on January 5 promised that the government would ensure at least 50% reservation of jobs for residents of the state.

“We did not make it mandatory but … we have a clause which mentions that priority must be given to locals during recruitment. There is no fixed percentage for the companies to follow,” said a senior industry department official.

Industry bodies do not think much of these announcements. “These are political statements and are impractical in terms of implementation. Companies investing in a state recruit people based on skills to ensure good profits. Companies do not go by caste or creed, nor do they see which state one is from,” said Assocham secretary general D S Rawat.

Tamil Nadu’s strength has always been its talent pool. But that’s for white collared jobs. When it comes to labour participation in industrial activity, capital has always flowed to places where workforce is available in plenty. While there is no command or order to recruit locals, some industries, like textile in Tirupur or the Sivakasi fireworks hub, have always opted for locals. But that’s mostly due to availability of cheap labour.

The position in 2020 Aug

Migrants power economy but local quotas curb job mobility, August 22, 2020: The Times of India

From: Migrants power economy but local quotas curb job mobility, August 22, 2020: The Times of India

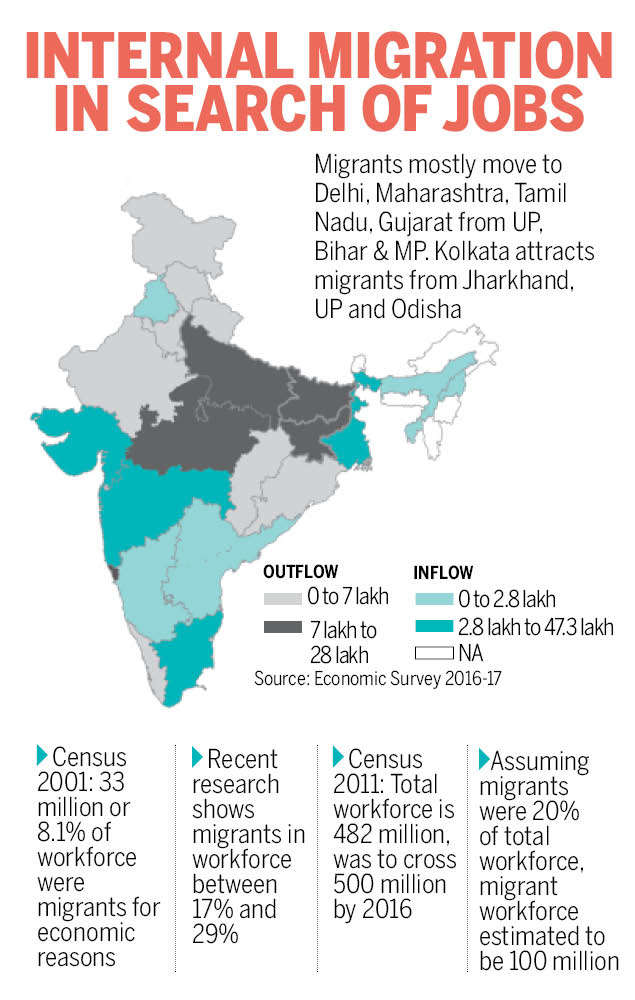

As efforts are made to bring the millions of migrant workers back to factories that power our economy, the paradox of states putting up policy pickets and trying to ring-fence jobs for locals is simultaneously playing out.

Consequently, while industrialists hire cars and buses and book seats on trains, and even planes, to fetch their workers from faraway corners of the country, the employment field for migrants is shrinking. Since 2019, at least five states — Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Haryana and MP — have announced or approved reservation for locals both in government jobs and private industrial units. There are also others like Goa and Himachal Pradesh that encourage employment of locals through incentives to industries.

For states reliant on migrants, reservations will be a challenge

Haryana’s reservation plan is the latest, with deputy CM Dushyant Chautala announcing on Friday that the government will introduce a bill in the assembly to give 75% reservation in private sector jobs to the state's youth. The promise was made by Chautala during the 2019 assembly election campaign and an ordinance to the effect was approved by the Haryana cabinet last month.

Earlier this week, Madhya Pradesh CM Shivraj Singh Chouhan announced that only "children of Madhya Pradesh" would henceforth be eligible for state government jobs. And while the pandemic’s impact on such policies — after the unprecedented upheaval it has caused in the job market — remains to be seen, there is the political factor. Madhya Pradesh is heading into byelections for 27 assembly seats and Chouhan’s announcement met with no opposition from his chief rival and predecessor Kamal Nath, who had, during his stint, said 70% reservation would be given to locals in private sector jobs. "At last, you have woken up to the issue of employment for youth after 15 years…" Nath reacted. In Maharashtra, one of India’s biggest migrant-receiving states, the Maha Vikas Aghadi government plans to introduce a law that will make it mandatory for the private sector to reserve 80% jobs for those domiciled in the state. "Domiciled", in this case, is defined as someone who has lived in the state for more than 15 years.

Last December, the Karnataka government amended the Karnataka Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Rules, 1961 to make it mandatory for private industries to give "priority" to Kannadigas in clerical and shop-floor jobs. The rule said people residing in Karnataka for not less than 15 years who can read, write, talk and understand Kannada are eligible for these jobs. The government had announced it would follow up with a law defining the quantum of reservation but that is yet to happen.

One state that did pass legislation for quota of up to 75% in both government and private jobs last year was Andhra Pradesh. The law, though, is yet to be implemented. Governments have powered through with these moves despite the legal questions. Reacting to Chouhan’s announcement, Congress MP and Supreme Court advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi told TOI, "Howsoever well-intentioned, a blanket ban permitting jobs to be held only by old and permanent residents of MP would be constitutionally (and I’m not talking politics here) invalid. The right to vocation, free movement and quasi-federal structure of the country allows some reservation and protective steps which are narrow, focused and targeted. A blanket ban would not be legally valid."

Asked about the legal soundness of reserving jobs for locals, PDT Achary, former Lok Sabha secretary general and an expert on the Constitution, said, "There is a provision under Article 16 of the Constitution which provides for reservation on the basis of place of residence. States can make laws to provide reservations under this provision. However, by definition, the objective of quota is to reserve a portion of the total jobs for people or groups that are inadequately represented. Reserving all jobs is a move violative of other provisions of the Constitution that grant freedom of movement, among others, and is, therefore, legally invalid. Moreover, such a decision does not square with the idea of nationalism that is being pushed at present." The legal question apart, implementing such laws is not easy because of factors like skill sets, availability of cheap labour and local job preferences. Gujarat, for instance, has had a policy since 1995 that says industries, both private and public, which have received government benefits must provide 85% employment to locals. But the policy has remained on paper and even PSUs do not follow it. CM Vijay Rupani has on several occasions attempted to enact a law but has faced stiff opposition from industrialists. Gujarat, as one of India’s largest manufacturing hubs, is also one of the country’s biggest migrant-receiving states and employs 50 lakh migrant workers.

For states heavily reliant on migrant workers, reservations will be a much bigger challenge than those who don’t. In Haryana, which has a huge requirement of technically skilled workers as one of India’s largest automobile manufacturing hubs, industrialists have, just like those in Gujarat, opposed job quota, saying it sent out the wrong message at a time when they were desperate to bring workers they have lost back to factories.

At the other end of the spectrum is Tamil Nadu, another huge automobile hub, which has not felt the need for quota because of the abundant availability of technical manpower. "In fact, technical workers from Tamil Nadu are engaged by companies like Sri City SEZ in AP close to the Tamil Nadu border as well as those in Bengaluru. Hence, it is superfluous to have reservation for locals in Tamil Nadu," a senior official with the industries department told TOI. "Even without reservations, majority of industries employ up to 90% locals. Migrant workers are used predominantly in sectors like construction and textiles, which locals are not keen on," the official added. Most states, including Tamil Nadu, run courses to enhance skill sets of locals.