Groundwater: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Water diviners and Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency

The Times of India, May 08 2016

Radheshyam Jadhav

In dry Latur, diviners strike gold, and sometimes water

Water diviner Channappa Mithkari's schedule is packed -he travels 24x7 as water scarcity gets acute in Latur in May . In the last couple of months, Channappa has `identified' around 600 sites in Latur and nearby villages to dig borewells with his `unique power' to find the location, depth and yield of groundwater.

Latur city has around 50,000 borewells and the number is growing.

In drought-hit Marathwa da, water diviners like Channappa are considered more `reliable' than the government's Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency (GSDA). While some use tools, there are many who claim to possess divine powers. A handful say that they can “identify“ underground water because of their specific blood group or because they are breech born. Channappa, who has been in this business since 1989, says: “With help of V-shaped copper-rods, I can sense the current of water. This is science, not superstition.“

However, when asked how many times he has failed in detecting water, Channappa evades the question saying he has further appointments. He identifies about 1,000 sites for digging borewells every year and his fees ranges between Rs 5,000 and 10,000. GSDA, on the other hand, charges Rs 1,0001,500 for finding water.

GSDA additional director S B Khandale admits that people have more faith in water diviners than government machinery , attributing their popularity to the fact that ground layers hold some water, which comes out after initial digging. “But this water doesn't last long and people never speak about it. During scientific digging, we go to the layer where sustainable water is available,“ he adds.

The GSDA prepares a hydr ological remote sensing map before conducting a field visit.Also, the well inventory is recorded to understand water table before finalising the location to dig a borewell. “We use electrical resistivity method as additional tool to ensure water availability and then correlate all study to identify the spot,“ says Khandale. But Satyavan Darphalkar, a retired zilla parishad headmaster in Osmanabad, describes GSDA 's methods as `irrational', saying: “The real science is in traditional knowledge. It is all about how the cosmos works. The direction of grass grown on ground shows the underground flow of water.Even government officers and agencies come to me seeking my advice“. Rajabhau Jadhav, a farmer in Latur with 60-acre farmland who has dug 18 borewells, is unsure of water divining but is ready to bet on it. “Only thing I know is that water diviner has helped me get water,“ says Jadhav .

Some farmers complain that they are forced to seek water diviners' help because of lack of response from GSDA office where their application is kept pending for months. “It is a fact that GSDA is too busy with government assignments in Latur and hence individual requests are delayed,“ admits Khandale. Ironically , almost all borewells in Latur district have gone dry , a reason why government has arranged for a special train to provide water. People have dug up 500 feet deep and still not struck water. But this has not stopped water diviners from `identifying' water spots.Latur based water expert Atul Deulgaonkar says the situation is scary and the government must strictly implement groundwater law.

Depleting groundwater

Depleting ground water levels cause for worry

Vishwa.Mohan

The Times of India Jul 27 2014

Ground water levels in various parts of India are declining as the country could not adequately recharge aquifers in deficit areas where it has been used for irrigation, industries and drinking water needs of the growing population over the years.

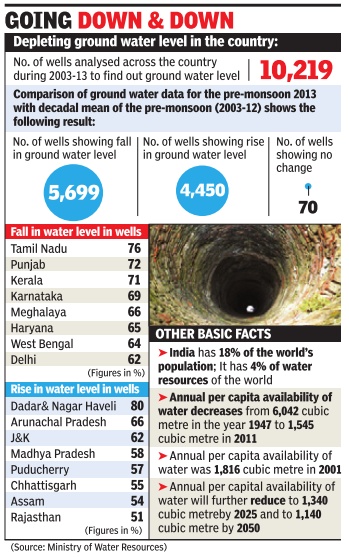

The Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) has told the ministry of water resources that around 56% of the wells, which are analyzed to keep a tab on ground water level, showed decline in its level in 2013 as compared to the average of preceding 10 years (200312) period.

The CGWB, a government agency , came to this conclusion by analyzing 10,219 wells across the country . It found that 5,699 wells had reported decline during that period. It also concluded that agriculture sector is the biggest user of water followed by domestic and industrial sector.

Sharing the Board's data, the ministry of water resources had last week told the Lok Sabha that the ground water was continuously being exploited due to population growth, increased industrialization and irrigation.

“As a result, ground water levels in various parts of the country are declining... The state governments have been advised to take suitable remedial measures to check ground water exploitation and ensure recharge of aquifers in water stressed areas“, said the MoS for water resources, Santosh Gangwar, in his written response to a question.

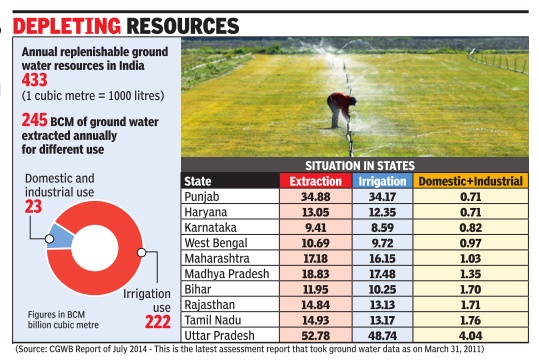

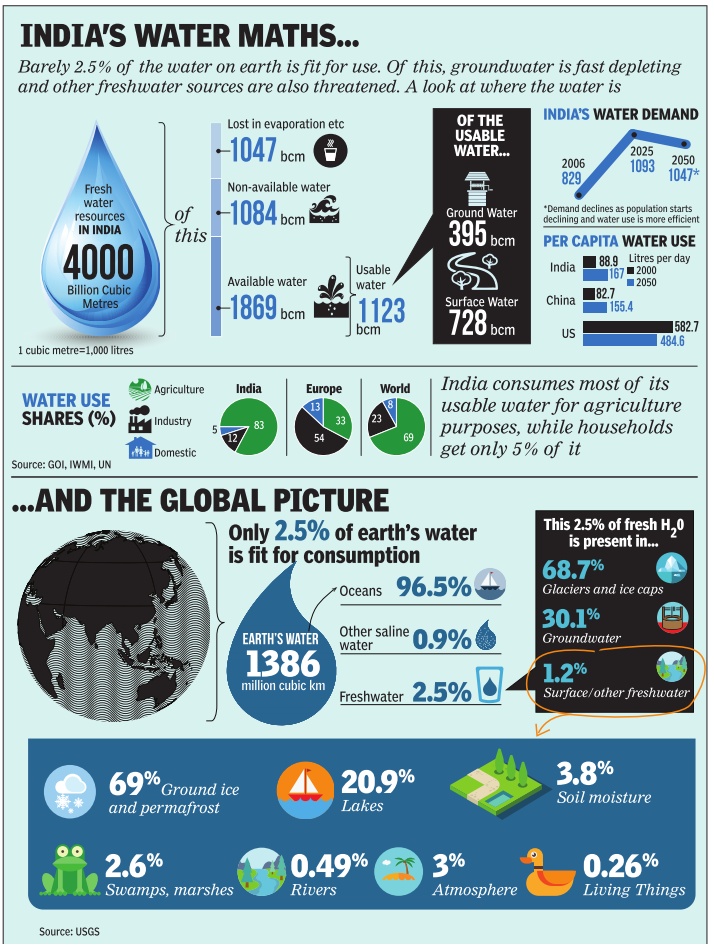

Depleting ground water level may be a real worry if one looks at the future demand of water in India. It is estimated that the country would need 1,180 billion cubic meter (BCM) of water annually by 2050. India has, at present, annual potential of 1,123 BCM of `utilizable' water with 690 BCM coming from surface water resources and remaining 433 BCM from ground water resources. In view of this projection, the country would not be able to meet its demand unless it recharges its aquifers and uses water more efficiently and judiciously. The government has decided to set up a National Bureau of Water Use Efficiency under its `National Water Mission' to promote water conservation in a big way , keeping in mind the future requirement.

The CGWB has, on its part, recently signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Indian Institute of Remote Sensing to facilitate a collaborative study “to assess the impact of ground water abstraction“ in India.

1951 onwards: rapid depletion

The Times of India, Apr 22 2016

Chittaranjan Tembhekar

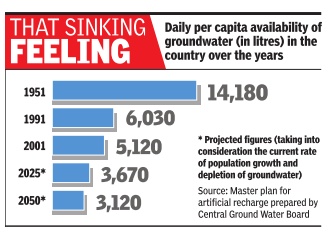

Do not be surprised if the country is forced to import drinking water by 2050, thanks to the fast-depleting groundwater stock that is expected to reduce to 3,120 litres per day a person by then. Data shows that today-going by 2001 figures -the daily per capita groundwater availability in the country has come down to 5,120 litres, about 35% of the 14,180 litres in 1951. In 1991, it was less than half of the 1951 stock. And by 2025, it is projected that the daily per capita availability will be just 25% of the base year. And the figures from a Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) study warn of a reduction to 22% by 2050, going by the present rate of exploitation of groundwater.

The depleting water beneath your feet is an indication of vanishing rainwater harvesting with ponds, lakes and wells, poor awareness, and reduced green cover, say experts.

A CGWB master plan to artificially recharge groundwater said: “Rapid development and use of groundwater resources for varied purposes has contributed, though, in expansion of irrigated agriculture, overall economic development and in improving the quality of life in urban India, the groundwater, which is the source for more than 85 per cent of rural domestic water requirements, 50 per cent of urban water requirements and over 50 per cent of irrigation requirements of the country, is depleting fast .“

Going by the fastgrowing population and their increasing demands, the day may not be far when per person availability dips to the actual use.

The extent and nature of the problem/ 1970-2015

ii) 1980- 2015: the level of India’s water below the ground;

iii) 1970-2015: Rise in average temperatures and decline in rainfall during the cropping season;

iv) 1970-2015: very hot and cold, dry and wet days during the monsoon;

v) Rainfall levels in India

From: June 21, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

i) Groundwater depletion in India vis-à-vis other countries, 2002-16;

ii) 1980- 2015: the level of India’s water below the ground;

iii) 1970-2015: Rise in average temperatures and decline in rainfall during the cropping season;

iv) 1970-2015: very hot and cold, dry and wet days during the monsoon;

v) Rainfall levels in India

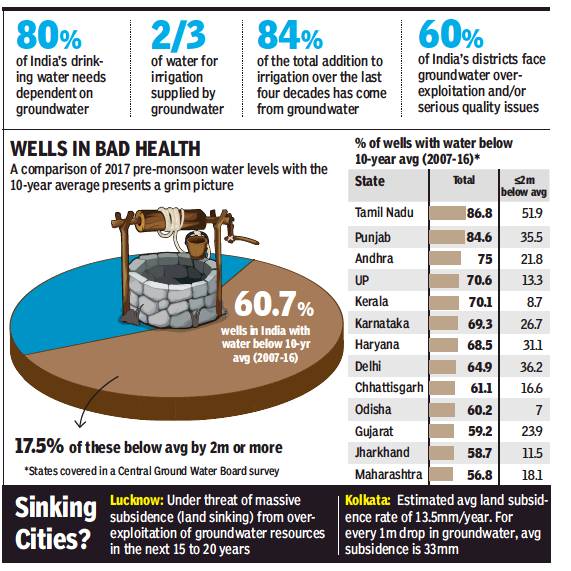

2007-16:The most reckless, user of groundwater

The world’s highest, and most reckless, user of groundwater, June 9, 2018: The Times of India

ii) A comparison of 2017 pre-monsoon water levels with the 10-year average

From: The world’s highest, and most reckless, user of groundwater, June 9, 2018: The Times of India

It is the backbone of India’s drinking water and irrigation supply systems, but overexploitation of groundwater is a threat to not only our food security but also the stability of the land, says Radheshyam Jadhav in the third of the series for TOI’s Water Positive campaign

India is standing on a slippery slope when it comes to our use of groundwater. Literally. Because in overexploiting this resource, we are risking more than just our ability to meet our future water needs. Groundwater overuse threatens the stability of the land.

Land subsidence due to groundwater pumping is a problem threatening several Asian cities. Beijing, Jakarta, Dhaka, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Shanghai in the recent past, and Tokyo in the 1960s-1970s have all faced the problem. Experts now predict that Indian cities, too, are likely to face land subsidence if overexploitation of groundwater continues unchecked.

Land subsidence and ground rupture can significantly affect the environment and safety of the people. Cases of land subsidence in western countries (Venice and Ravenna in Italy, Houston in US) and in Asia show that the only check against it is the shutdown of pumping wells and supply of potable water through alternative sources.

According to Italy-based scientist Pietro Teatini, land subsidence can be significant in coastal zones along the Bay of Bengal, such as the deltaic regions of the Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna and Cauvery rivers. Kolkata is already suffering, he says, with sinking rates of 10-20mm/year. Ground rupture has been observed in the Indian hinterland, for example in Uttar Pradesh, adds Teatini.

Meanwhile, as Indian cities continue to drill deep for water, more than 60% of wells analysed by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) had levels lower than the decadal average (2007-2016) and about a sixth

(17.5%) had levels 2 metres or more below the average. These 2017 pre-monsoon numbers are a cause for concern considering that 90% of rural domestic water use is based on groundwater and 70% of water for agriculture comes from aquifers.

Of the 14,465 wells CGWB surveyed, water levels were down in 8,785. Among the major states, Tamil Nadu had 87% of wells showing a dip in groundwater followed by Punjab (85%). Just 38% of the wells across states showed a rise in water levels over the decadal average. Even among these, the overwhelming majority are less than 2 metres above the average. A recent report warns of a major crisis due to over-extraction and groundwater contamination covering nearly 60% of all districts. It says there is mounting evidence to suggest that 50% of urban water usage comes from groundwater.

The South Asia Ground Water Forum says the region is the largest user of groundwater, accounting for nearly 50% of the total groundwater pumped for irrigation globally. Groundwater abstracted in the Indo-Gangetic basin is about onefourth of the global total.

India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh are, respectively, the first, fourth, and sixth largest users of groundwater globally. India pumps more than the US and China combined — the second and third-largest users, respectively.

2017/ Extraction of groundwater

December 17, 2017: The Times of India

230 km3--- That’s how much groundwater India extracts in a year. It’s roughly a fourth of the world’s annual groundwater consumption, and 24 times the capacity of Gobind Sagar, the reservoir of Bhakra Dam.

Abuse of groundwater

The extent of the problem, state-wise

The Times of India, Apr 21 2016

Not only sugarcane states, others too abuse groundwater

Vishwa Mohan

Over 90% of the extracted groundwater in India is used for irrigation.Though this has never been a secret, the quantum of groundwater use in different states shows that the culprits are not only the sugarcane producing states like Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka. The onus of abusing groundwater resources also lies with wheat, rice, maize and oilseeds producing states like Punjab and Haryana. Groundwater use pattern of these two states show they are extracting more water than can be replenished, driving home the urgent need for farmers to adopt efficient micro-irrigation systems like drip and sprinkler which can help conserve water.

The Cen tral Ground Water Board (CGWB) in its latest assessment report noted that though Punjab has only 20.32 Billion Cubic Meter (BCM) of annual groundwater availability , it extracts 34.88 BCM annually . Similarly, Haryana extracts 13.05 BCM as against the availability of only 9.79 BCM. Of this, Punjab uses 34.17 BCM for its irrigation needs, while Haryana uses 12.35 BCM of groundwater it extracts annually for the same purpose.

Referring to such indiscriminate use of groundwater, the Union water resources minister Uma Bharti on Wednesday expressed her concern that prosperous states like Haryana and Punjab have “abused“ groundwater over the years and now most of their blocks fall under `dark' zones or highly groundwater exploited areas.

“More than 70% of their blocks are falling under dark zones now. A state like Maharashtra had reported water deficit situations earlier as well. But Punjab and Haryana tell us a tragic story,“ Bharti said while addressing the `India Water Forum', organised here by The Energy and Resources Institute, on the ongoing water crisis.

Though the situation of groundwater use is more or less same in many states, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan are especially guilty because of the excessive pumping causing severe groundwater depletion.

What's the way forward?

Sudhir Panwar, Lucknow Uni versity professor and president of the Kisan Jagriti Manch, said government policy should be tweaked in such a way that farmers could conveniently move towards sprinkler and drip irrigation systems the twin methods of using water in most judicious way in agriculture.

Delhi, Rajasthan, Haryana: extraction rises

The Times of India, Apr 17 2016

Vishwa Mohan

Delhi, Rajasthan, Haryana going the Latur way as groundwater extraction rises

Per Capita Availability Declining

As water trains and tankers help battle Latur's worst drought ever, rampant extraction of groundwater could soon push Delhi, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan towards a similar harrowing shortage of water.

Analysis of water use by different states shows that a gradual decline in per capita availability could leave these states in the same precarious position as the Marathwada region of Maharashtra, which has faced two consecutive years of drought.

The latest assessment of the country's dy namic groundwa ter resources, performed by Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), shows that these states, in fact, consume much more groundwater than their rechargeable limit every year, making them vulnerable to severe water scarcity.

Delhi recently witnessed how perilous the situation can get when agitating Jats cut off its water supply from Haryana. It could get much worse in the future if one looks at the way Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan have been drawing water from the ground.

Referring to the situation in Punjab and Haryana, former CGWB scientist Shashank Shekhar said, “Indiscriminate use of water in agriculture is a major concern. The practice of provid ing free electricity to farmers must be immediately discontinued to stop the misuse of groundwater in Punjab.“

“Since agriculture consumes the maximum water across the country , the use of drip irrigation and sprinklers must be encouraged through various incentives,“ he added.

Though the record of Maharashtra is better than its northern counterparts in terms of groundwater extraction, Latur district had been extracting more than the state average and now it does not have water to draw from existing borewells.

“There is need to drill a number of borewells in Latur with the help of geological data and remote sensing maps on prevailing hydrological information,“ said Shekhar, currently an assistant professor in Delhi University's geology department. “Many of them may fail to trace water.But there are chances that a few of them will tap the water bearing rocks,“ he added.

Though the exact estimate of groundwater resources can only be made after completion of the ongoing exercise of aquifer (underground layer of water-bearing rock) mapping, the Centre is, meanwhile, looking at various options to conserve water in a big way.One option is to introduce the tank-based water conservation model practised by the 11th century Kakatiya dynasty in Warangal area.

Under the Kakatiya dynasty, the then kings had promoted a small tank-based irrigation system which turned out to be a prudent method. Inter-connected rain-fed tanks were built to store rainwater. The Telangana government has, in fact, already launched `Mission Kakatiya' that aims to de-silt the existing tanks and build more such tanks to conserve water.

India among worst offenders

Subodh Varma, India uses up more groundwater than US & China, May 23, 2017: The Times of India

Indiscriminate Withdrawal Of Groundwater Means India May Run Out Of Its Supply Of Usable Water In A Few Years

Right on the edge of the Ganga basin that spans 11 Indian states lies Naujhil block, a few kilometres west of Yamuna in UP's Mathura district. You would think this is a blessed location with plentiful water all round.With its 17 tributaries, including the Yamuna, Ganga's catchment area has about 525 billion cubic metres (bcm) of surface water and about 171 bcm of groundwater. On average, it receives a million cubic metres of rainfall on every square kilometre. But Naujhil block is a declared “dark zone“, that is, its groundwater extraction far exceeds the recharging rate and use of electricity for pumping water is not permitted.Because of heavy withdrawal, the groundwater is very saline now.

Subhash Nauwar, a farmer from Managarhi village in the area, says, “About 35-40 years ago, there was no problem. This is the khadar (floodplain) of the Yamuna and its water would recharge the groundwater sources. But people wanted more crops, so a bund was built to prevent flooding. Now there is no water.“

It's bizarre. Most residents of Managarhi use bottled water for drinking and cooking, as if they were living in a desert and not in one of the world's most water-rich plains.

This water scarcity is spreading across India, smothering idyllic villages and high-rise city habitats in equal measure. No Indian city supplies 24x7 drinkable water to all of its residents. In many cities, including Bengaluru and Chennai, water scarcity has reached crisis levels and in pampered Delhi, every summer brings intense water scarcity for the disadvantaged sections. Meanwhile, in rural India, zooming agricultural production over the years has mostly been fuelled by heavy use of groundwater because not enough investment was made for using surface and rainwater through canals and reservoirs.

Now, take a look at India's water equation: after accounting for losses due to evaporation and unusable water like brackish water or swamp water, the total usable water available in the country is 1,123 bcm, while the total water consumption in 2006 was 829 bcm, projected to rise to 1,093 bcm by 2020. So, in just a few years, India will reach its limit of water consumption because water supply cannot be increased. It is a definite, finite resource.

Increase in population has, of course, contributed to the situation reaching these dire straits, but a closer look will reveal gross mismanagement and neglect by governments, coupled with an unbridled destruction of resources as if there is no tomorrow.

Take rainwater for instance. Just 18% of rainwater is used effectively while 48% enters the river systems, most of which just flows into the ocean, according to Narayan Hegde, a water expert with the BAIF Research Development Foundation.

“Farm ponds, percolation tanks, water reservoirs and small and medium-sized dams can help retain more sur face water while increasing the groundwater recharge,“ he told TOI.

This would ease some of the pressure off groundwater usage that has pushed 29% of the country's blocks into the “over-exploited“ category , that is, where groundwater withdrawal is more than the possible recharge. This indiscriminate withdrawal, as in Naujhil, has led India to showing an annual groundwater usage that is more than the combined usage by the US and China. Studies by Nasa using satellite imagery show that the Indus basin, which includes the high food producing states of Punjab and Haryana, is one of the most stressed aquifers in the world. If the current trends continue, by 2030 nearly 60% of Indian aquifers will be in a critical condition.This means that some 25% of the agricultural production will be at risk -a devastating scenario.

India's cities are teetering on the brink of an unimaginable water crisis because of unplanned growth and low priority to provision of safe drinking water. Loss due to leaks in the supply systems and wasteful consumption practices pose a serious and untackled problem. Cities also symbolise the injustice of water distribution with well-heeled localities getting as much as 6-8 times more water than the poorer localities.

Here, too, rainwater harvesting can play an important role in supplementing municipal supplies and taking the load off precious groundwater resources.Take the example of Delhi. It receives a mindboggling 690 billion litres of rainfall every year. Harvesting even 25% of this would yield 172 billion litres. With an average demand of about 5 billion litres per day , this could just be sufficient to tide over a hot, waterless summer month.

A mix of traditional and modern technologies needs to be urgently put in place to tackle India's impending water crisis, argues Hegde. This includes watershed development programmes, increasing the efficiency of irrigation by replacing the prevalent flood irrigation with drip or sprinkler systems and creation of desalination plants to convert seawater into drinkable sweet water.

Gurgaon illegally draws 4cr litre daily

Shilpy Arora, Ggn illegally draws 4cr litre groundwater daily, June 6, 2017: The Times of India

Unauthorised Borewells Dug Up; Water Table Falls 16M In 10 Yrs

Four crore litres of groundwater are drawn out every day in Gurgaon through illegal borewells to meet a big gap in demand and supply . And that's only a conservative estimate as the city's population is increasing continuously .

Now, add to this people who will move into lakhs of flats in the city's new sectors along the Dwarka expressway , Southern Peripheral Road and Sohna Road in the next few years and thousands more who currently live in unauthorized colonies.This shows why availability of water could soon become the single largest challenge for the city , probably bigger even than air pollution.

For the record, the city's groundwater fell 16 metres in 10 years to 34.84 metres below ground level in 2015, from 18.77 in 2005.

Last week, a study jointly conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Gurgaon First under the aegis of MCG on the city's rapid growth and the strain that has put on its resources, feared Gurgaon would turn into a “living hell“ if immediate steps were not taken to make this growth sustainable.

Water would be a good starting point.

Gurgaon needs at least 270 MLD (million litres per day) of water for household use. Industrial and commer cial establishments need another 99 MLD, making the city's total requirement 369 MLD. This is with an estimate that the city's current population is 20 lakh, which in reality is likely to be more.

Water is supplied to the city from two treatment plants -Basai and Chandu Budhera. While Basai provides nearly 225 MLD, Chandu Budhera supplies 99 MLD.Registered tubewells extract about 5 MLD. So there is a gap of 40 MLD, which is met by water tankers through illegal borewells. That is 4 crore litres, which is equivalent to the need of nearly 3 lakh people going by the standard per capita consumption of 135 litres a day .

Even though a 2012 high court order prohibited extraction of groundwater by setting up borewells, for both construction and residential purposes, extraction is rampant in the city . TOI found out there are over 40 water tanker services in the city .And this, despite authorities claiming to have banned private water tankers some four years ago.

But tankers have become a part of daily life because of the faltering water supply , of which this summer has thrown up ample instances.“Huda supply doesn't meet 60% of the demand in summers. We, therefore, have to fall back on groundwater. We try to meet the demand through registered borewells, but it's difficult to manage witho ut private water tankers,“ said R S Rathee, president, DLF Qutab Enclave RWA.

Subhash Piplani, a former sub-divisional officer at Huda, said, “The demand-supply gap is filled through illegal ground water extraction. What would you do when you don't get water supply? Wouldn't you call tankers? These tankers are called by people as authorities have failed to meet demand.“

According to a Central Ground Water Authority (CGWB) report released in 2016, Gurgaon is situated in a semi-arid area. Rain is the main source of recharging groundwater. But as a result of heavy urbanisation and industrialisation the run-off from rain goes straight to sewers or storm water drains, reducing the contribution of rainfall to groundwater recharge.

“Net annual withdrawal is more than net annual recharge. During the last 20 years, groundwater level has declined across the district, at a rate of 0.77-1.2m per year. So there's a need to take measures to arrest the fall in the groundwater level. Recharging groundwater artificially is one such measure,“ said the report.

Presently , the city has on ly 1,000 rainwater harvesting pits that recharge groundwater for not more than 20-25 days a year. “Ever since Gurgaon was founded, private establishments and developers, and now even residents, have been guzzling groundwater without realising the need to harvest the resource. Even if we harvest half the rainwater the city receives during the monsoon, our dependence on groundwater will fall drastically,“ said Vivek Kamboj, a city-based environmentalist.

Some activists raised the need for authorities to provide basic scientific tools for rainwater harvesting.Sushmita Sen, deputy programme manager at CSE, said, “There is a need to adopt a sector-wise rainwater harvesting system. Authorities, NGOs and residents should come together to ensure rainwater is harvested properly and all scientific tools are made available for rainwater recharge.“

Composite Water Index: NITI Aayog

FY 16-17/ India facing "worst" water crisis

Jacob Koshy, India faces worst water crisis: NITI Aayog, June 14, 2018: The Hindu

From: Jacob Koshy, India faces worst water crisis: NITI Aayog, June 14, 2018: The Hindu

Demand for potable water will outstrip supply by 2030, says study

The NITI Aayog released the results of a study warning that India is facing its ‘worst’ water crisis in history and that demand for potable water will outstrip supply by 2030 if steps are not taken.

Nearly 600 million Indians faced high to extreme water stress and about 2,00,000 people died every year due to inadequate access to safe water. Twenty-one cities, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad will run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people, the study noted. If matters are to continue, there will be a 6% loss in the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2050, the report says.

70% contaminated

Moreover, critical groundwater resources, which accounted for 40% of India’s water supply, are being depleted at “unsustainable” rates and up to 70% of India’s water supply is “contaminated,” the report says.

The NITI Aayog’s observations are part of a study that ranked 24 States on how well they managed their water. Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh took the top three spots, in that order, and Jharkhand, Bihar and Haryana came in last in the ‘Non-Himalayan States’ category. Himachal Pradesh — which is facing one of its worst water crises this year — led a separate 8-member list of States clubbed together as ‘North-Eastern and Himalayan.’ These two categories were made to account for different hydrological conditions across the two groups.

Low performers

About 60% of the States were marked as “low performers” and this was cause for “alarm,” according to the report. Many of the States that performed badly on the index — Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Chhattisgarh — accounted for 20-30% of India’s agricultural output. “Given the combination of rapidly declining groundwater levels and limited policy action…this is likely to be a significant food security risk for the country,” the report says.

On the other hand, the index noted, several of the high and medium performers — Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana — had faced droughts in recent years. Therefore, a lack of water was not necessary grounds for States not initiating action on conservation. Most of the gains registered by the States were due to their restoration of surface water bodies, watershed development activities and rural water supply provision.

Envisioned as an annual exercise, the Composite Water Management Index (CWMI), to evaluate States, has been developed by the NITI Aayog and comprises 9 broad sectors with 28 different indicators covering various aspects of groundwater, restoration of water bodies, irrigation, farm practices, drinking water, policy and governance. “While Jharkhand and Rajasthan may have scored low, they have made remarkable improvement when compared over two years,” said Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog.

Other experts said that unless India woke up to its water crisis, disaster loomed. “There is great awareness now about air pollution, however, India’s water crisis does not get that kind of attention,” said Rajiv Kumar, Vice-Chairman, NITI Aayog.

How drinkable is it?

33% is undrinkable

Groundwater in 33% of India undrinkable

Iron, Fluoride, Salinity, Arsenic Beyond Tolerance Levels In Many Districts: Govt

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

New Delhi: Groundwater in more than a third of Indian districts is not fit for drinking. The government, in reply to a parliamentary question, admitted that iron levels in ground water are higher than those prescribed in 254 districts while fluoride levels have breached the safe level in 224 districts.

The alarming situation could bring trouble for the government, which has promised to provide drinking water to all habitations by 2012 under the millennium development goals.

While groundwater is not the only source of drinking water that government utilizes, it is one of the key supplies and the dependence on ground water has been increasing over years.

The government, in its reply, said salinity had risen beyond tolerance levels in 162 districts while arsenic levels were found higher than permissible limits in 34 districts. States like Rajasthan, Karnataka and Gujarat seemed to be worst affected. Twenty-one of the 26 districts of Gujarat were found to have dangerous salinity levels and 18 had breached safe fluoride levels. The Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) found 21 of 31 districts in the southern state of Karnataka to be contaminated with iron and 20 districts with higher levels of fluoride. In the case of Rajasthan, groundwater in 27 districts was found to be too saline, 30 districts had higher levels of fluoride and 28 suffered from iron contamination.

The national capital does not fare any better, with five of its nine districts showing fluoride contamination and two showing salinity. Pockets of all the nine districts had high iron content.

While urban centres in the country deploy water treatment systems before supplying water to homes, the costs of cleaning up as well as chances of contamination remain. Removal of heavy metals like arsenic, though, remains a problem the government is unable to tackle where the source of water is only from the ground aquifers.

Experts have warned that lopsided water management has led to depletion of ground water aquifers and this, in many cases, has caused increasing contamination as people dig deeper into the ground to extract water. Cases of habitations that were provided drinking water sources based on groundwater slipping back have also been highlighted recently.

Breaching Levels

Iron levels in ground water higher than those prescribed in

254 districts

Fluoride has breached the safe level in 224 districts

Salinity beyond tolerance levels in 162 districts

Arsenic levels higher than permissible limits in 34 districts

Rajasthan, Karnataka, Gujarat worst affected

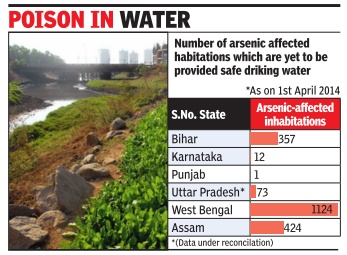

Arsenic in groundwater

Mohua Chatterjee, December 12, 2014

The parliamentary estimates committee headed by BJP MP Murli Manohar Joshi, in its first report on arsenic in groundwater, has criticized the Centre for “neglecting“ the serious issue that impacts at least 7 crore people across six states, according to CSIR estimates (data from different ministries and departments on the subject varies widely , the committee found). The panel has recommended that the Centre take up the issue on war footing through a national task force that can work on mission-mode from collating date to taking remedial measures to providing for health care to affected people. The committee has suggested that the issue be dealt with at the central level, instead of asking states alone to tackle the problem. Joshi said, “To say water is a state is sue is no logic, given the scale of the problem, the Centre cannot escape its responsibility to provide safe drinking water for 7 crore people, which is their fundamental right.” He was speaking at a press conference after the report was tabled.

The report has recommended that a national task force be set up on a time-bound basis that will work on mission mode on the issue that affects people, plants, animals and all else around it. The committee has also recommended for a central fund allocation for the purpose. At a press conference, Joshi said, the Centre cannot escape its responsibility to provide safe, potable water to 7 crore Indians which is there fundamental right.

Toxins in groundwater

Vishwa Mohan, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

From: Vishwa Mohan, July 31, 2018: The Times of India

Discharge of toxic elements from industries and landfills and diffused sources of pollution like fertilisers and pesticides over the years has resulted in high levels of contamination of ground water with the level of nitrates exceeding permissible limits in more than 50% districts of India.

Apart from nitrate contamination, the presence of fluoride, iron, arsenic and heavy metals has also touched worrying levels, information provided by the government to Parliament reveals.

According to WHO, nitrate in drinking water can cause methaemoglobinaemia or the decreased ability of blood to carry oxygen around the body.

Details show seven of Delhi’s 11 districts have reported excess fluoride, eight excess nitrate, two excess arsenic and three excess lead in ground water.

Though the government noted that “ground water in major parts of the country is potable”, it underlined the contamination in many parts due to presence of one or more toxic elements. “... Some parts of various states are contaminated by salinity, arsenic, fluoride, iron, nitrate and heavy metals beyond permissible limits of the Bureau of Indian Standards”, said junior minister for water resources Arjun Ram Meghwal.

Drinking of arsenic-rich water over a long period results in various health effects including skin cancer, cancers of the bladder, kidney and lung, and diseases of the blood vessels of the legs and feet, and possibly also diabetes, high blood pressure and reproductive disorders, according to WHO.

The chemical quality of groundwater is monitored once a year by the Central Ground Water Board through a network of about 15,000 observation wells located across the country.

The minister said industrial discharges, landfills, fertilisers and pesticides are “possible sources of contamination of ground water”.

Water expert Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People said, “In areas where GW is already contaminated, there can be several treatment related solutions, but the least expensive solution is rainwater harvesting…”

India and the world

About 13 of the world's 37 biggest aquifers, including two in India, are being seriously depleted by irrigation and other uses, much faster than they can be recharged by rain or runoff. There were 21 major groundwater basins -in red, orange, and yellow -that lost water faster than they could be recharged between 2003 and 2013.Sixteen major aquifers (in blue) by contrast, gained water during that period.

Groundwater levels, trends: state-wise

Himachal Pradesh, March 2016

The Times of India, Mar 7, 2016

Anand Bodh

Sharp drop in groundwater level in HP

Climate change has started ringing alarm bells in Himachal Pradesh as not only rain and snow pattern has been affected, but now groundwater level too has decreased significantly. The groundwater resources occur mainly in unconsolidated sediments of inter-mountain valleys and sub-mountain tract.Kangra, Una, Hamirpur, Bilaspur, Mandi, Solan and Sirmaur districts, particularly valley areas, depend on groundwater for their needs. Sarkaghat BJP MLA Inder Singh had asked a question during the ongoing budget session about the decreasing groundwater level in the state.He had also sought details of surveys conducted by the irrigation and public health department on the issue, besides steps taken by the department in this regard.

In a written reply, irrigation and public health minister Vidya Stokes informed the house that in many valleys and areas of the state declining trend of groundwater level had been found. She added that the de partment along with Central Groundwater Board had carried dynamic groundwater resource estimation.

To prevent the declining ground water level, the state government has approved detailed project report of about `139 crore to construct 956 rain water conservation structures, she said, adding that already 562 rain water conservation structures have been constructed at a cost of about ` 25 crore.

A report prepared by the Central Ground Water Board has stated that due to extensive groundwater useage for irrigation and the recently set up industrial units in Una valley, the levels are likely to further show depleting trend. There is an urgent need for the state government to initiate water level monitoring network both in shallow and deep aquifers to monitor its behavior on short as well as long term basis, it added.

Studies state that as on March 2011, the stage of groundwater development in Una and Hum valleys of the district was 108% and 99%, respectively, and falls under critical category of development.

There is, thus, no scope for further ground water development by constructing additional wells and tube wells in the area.

Another report on Solan district by Central Ground Water Board said that in many parts availability of water during summer is limited, particularly in hilly areas during drought low rain fall years. There is thus, immediate need to conserve and augment water resources.

It said that presently, large development of ground water is observed in industrial belts of Nalagarh valley, wherein fall of water level down to six meters have been observed in parts.

Thus, depletion in ground water levels and also vulnerability to ground water pollution, are the major issues in this industrial belt.

Report said that in alluvial areas of Nalagarh valley, though there is scope for ground water development, as stage of ground water development is only 52%, however, there is need to adopt cautious approach and phased manner development of ground water in view of depleting water levels in some parts.

This decline can be attributed to fast pace of development in recent years, both in agriculture sector and industrial sector.

Rules for extraction

2017: ‘privatisation of a common resource?’

It Will Hasten Crisis, Claim Activists

Seeking to have uniform regulatory framework on groundwater use across the country , the Centre has come out with draft guidelines which stipulate existing and new industries, infrastructure and mining projects have to obtain a `no-objection certificate' (NOC) from district and state-level authorities for drawing groundwater.

The draft also proposes to levy a new water conservation fee based on quantum of groundwater extrac tion in lieu of existing provision of creating recharge mechanism, including construction of artificial recharge structures, by those undertaking projects.

The proposed fee is based on water use quantity and groundwater capacity of particular areazone. The amount, therefore, varies from Rs 1 to Rs 6 per cubic metre. The funds raised through this new fee will be used by states for effective ground water management.

At present, the Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA) has been granting NOC for withdrawal of water by industriesinfrastructuremining projects. The new guidelines will decentralise the process of issuing NOC. The CGWA, which issued the draft guidelines, claimed the move was considered “necessary and expe dient“ to ensure a uniform regulatory framework across the country so that the discriminatory practices in regulation are either mitigated or minimised. Once the final guidelines are notified, the revenue heads of the district, state nodal agency State Ground Water Authority and the CGWA will be the NOC issuing authorities depending on the quantum of ground water extraction.The final guidelines will be notified by the CGWA after analysing comments of stakeholders on this draft after 60 days. Though the CGWA claimed that the new move would mitigate discriminatory practices in regulation, water experts differed and said that the new guidelines would go towards privatisation of the common resource.

“These guidelines will further destroy our groundwater lifeline, bringing the crisis much faster than it would have been without this...The district and state level entities have no capacity to understand the implications of giving NOCs“, said Himanshu Thakkar of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People.

The draft guidelines exempt farmers from obtaining NOCs. It calls for medium and large farmers to adopt water conservation measures.

Salinity

Godavari, Krishna islands

They live in the midst of coconut lagoons and man groves. But life's not rosy for the lakhs living in islands on the mouth of the Godavari and Krishna in Andhra Pradesh.

The two major islands and over two dozen islets face a severe shortage of potable water almost round the year. It gets worse during summer and in years when rain is deficient. The river water is not an option because currents carry the sea water right up the mouth and upstream turning the river saline around island villages up to 15 km away from the Bay of Bengal.

Ask Bomidi Sri Lakshmi, a farmer from Edurumondi, an island in the Krishna. She wakes up early and marches to a water pit fed by a freshwater aquifer. On other islandsmany of which do not have freshwater pits--they have to queue up at water tankers supplied by philanthropists or ferry water from the mainland by boats. Only the main islands--Diviseema (Krishna) and Konaseema (Godavari), two major riverine islands in south India--are connected by bridges which allow residents here to get piped supply .

There are no water treatment or desalination plants on the islands or islets. As a result, vast stretches of farmlands have turned barren; cattle are in dire straits. “Sometimes, the animals are forced to drink from the highly polluted river. The only source of freshwater for the villages is the channels from the main canals of Prakasam Barrage, some 50 km upstream,“ says Venkateswaramma, a farmer from Gollamanda.

The last time the Krishna estuary had potable freshwater was in October 2009 when the river was in spate.

Experts blame the scarcity of potable water on the reduced inflows from upstream, frequent failure of the monsoon, seawater ingress, overdrawing of groundwater and loss of vegetation. “The scarcity is mostly due to man-made factors. The available water cannot be used even for washing clothes and utensils,“ say S Srinivasa Rao, an academician from Vijayawada.

Uranium contamination, state-wise

2018/ Rajasthan

Jacob Koshy, Uranium contamination in Rajasthan groundwater, finds study, June 8, 2018: The Hindu

From: Jacob Koshy, Uranium contamination in Rajasthan groundwater, finds study, June 8, 2018: The Hindu

Many parts of Rajasthan may have high uranium levels in their groundwater, according to a study by researchers at the Duke University in North Carolina, United States, and the Central Groundwater Board of India.

The main source of uranium contamination was “natural,” but human factors such as groundwater table decline and nitrate pollution could be worsening the problem.

“Nearly a third of all water wells we tested in one State, Rajasthan, contained uranium levels that exceed the World Health Organization (WHO) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) safe drinking water standards,” said Avner Vengosh, a professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, in a press statement.

“By analysing previous water quality studies, we also identified aquifers contaminated with similarly high levels of uranium in 26 other districts in north-western India and nine districts in southern or south-eastern India,” he said.

While previous studies have referred to high uranium levels in some districts of India, this analysis gave a bird’s eye view into the extent of such contamination. The WHO has set a provisional safe drinking water standard of 30 micrograms of uranium per litre, a level that is consistent with the U.S. EPA standards. Despite this, uranium is not yet included in the list of contaminants monitored under the Bureau of Indian Standards’ Drinking Water Specifications.

Mr. Vengosh and his colleagues published their peer-reviewed study on May 11 in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

See also

Groundwater: India