Hindu: Bengal

(Created page with "This article is an extract from {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> '''THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL.''' <br/> By H.H. RISLEY,<br/> INDIAN C...") |

m (Pdewan moved page Hindu to Hindu: Bengal without leaving a redirect) |

Latest revision as of 11:44, 24 January 2022

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

[edit] Hindu

THE Hindus of Bengal claim to be pure Aryans, but the Hindus of Upper India repudiate any relationship with them. The Aryan immigration extended gradually throughout Bengal, and the tie which bound the settlers to their faith and peculiar usages was relaxed by residence among aliens. The example of races untrammelled by caste, or religious scruples, also led them to shake off all bonds, and assert greater freedom of action. The priesthood formed illegal connections, and neglected their religious duties; while the mixed offspring observed none of the Brahmanical ordinances.

In the tenth century corruption and irrreligion being universal, Adisura introduced priests, trained in the orthodox school of Kanauj, to reform and educate the people. But the arrival of a small body of religious teachers did little towards elevating the Brahmans, or laity, and in the twelfth century Ballal Sen found only nineteen families of the Rarhi Brahmans living in strict obedience to all that their religion demanded. These families were raised to the highest rank, but those who had forfeited all respect, and formed illegal marriages, were reduced to secondary, or even lower grades. The innovations made by this monarch only affected the Rarhi and Varendra Sreni, or orders, for the Vaidika and Bhat, refusing to be classified by a Vaidya, retired into the hill countries of Silhet and Orissa; and the other tribes, who had become hopelessly demoralized, were left untouched.

The chief object of the reform organised by Ballal Sen was the creation of an aristocratic and powerful hierarchy, placed in such a position of dignity that no misdemeanor, and no immorality, could deprive it of hereditary privileges, or the reverence of the lower classes. An illegal marriage was the only transgression entailing loss of rank and forfeiture of respect. No provision was made in this new code for the elevation of the lower ranks, when families became extinct, consequently, as Kulin houses disappeared, the difficulty of procuring husbands for daughters vastly increased, and when the third re-organisation of the order was made by Devi Vara, in the fourteenth century, polygamy, and the buying and selling of wives, was the engrosssng occupation of the twice-born Brahmans.

In spite of these successive endeavours for securing the purity of the Bengali Brahmans, it is remarkable that Kanaujiya, and other Brahmanical tribes of Hindustan, have always despised and repudiated any connection with their Bengali brethren. In their religious and domestic ceremonies, habits of life, and mode of living, Bengali Brahmans are quite distinct from any of the other tribes, and the only point of attachment between them is when outcast Kanaujiyas marry Srotriya maidens, and become absorbed into their ranks. Although clinging with characteristic pertinacity to all the prerogatives of their order, modern ideas are gradually undermining their bulwarks, and the exclusive rules are step by step yielding to education and the progress of the nation.

Kulin Brahmans are now found adorning the bench, the bar, and the medical profession, and, while proving useful members of society, exert a rare influence for good over their Hindu countrymen.

Besides the Rarhi and Varendra tribes, there were in Bengal four inferior classes of Brahmans left out of the organisation of Ballal Sen, namely, the Vaidika, Sapta-sati, Acharya, and Agradana. The three first claim to have been resident in Bengal before the reign of that monarch, and the services of all the four are still required by the Rarhi Sreni at many important ceremonies. The Vaidika is the only division that has preserved an honourable position; but whether this is owing to their being descendants of Kanaujiya Brahmans, to the respectability and decency of their lives, or to their independence of character, is very doubtful.

They decline to give their daughters in marriage to the Kulin Brahmans of Bikrampur, and refuse to act for any clean Sudra, or Brahman, unless his family can trace their origin to Kanauj. The Sapta-sati, undoubtedly one of the oldest Bengali septs, is gradually being absorbed by the Srotriya, and few confess they belong to it. In a few years they will be sought for in vain. The Acharya and Agradana are Brahmans only in name. The former are chiefly employed in secular occupations, and in discharging duties useful, but unknown to the Vedas or Puranas. The Agradana, claiming to rank above Acharya, is the most despised of the sacred order, and clean Sudras, as well as Patit Brahmans, would be degraded by eating with them.

The Patit Brahmans are the most active representatives of the Hindu hierarchy, having fallen from their high estate by neglecting religious duties, officiating in Sudra temples, marrying into inferior grades, or acting as Purohits to the Varna Sankara.1 The loss of rank has in some respects been mitigated by the affection and devotion of the laity, and by the high social position given by the caste for which they officiate. It is to this class, abandoned by the Kulins, that India owes the spread of the Hindu religion among the wild tribes of the Tarai, Assam, and Eastern Bengal, and the conversion of the semi-Hinduized aborigines throughout Bengal.

Bad and immoral many of these Sudra Brahmans are, but as a class their lives are not one long course of depravity and selfish indulgence, as is too often the case with the Kulins. Education has made no progress among them, and holding the position they do, concession to the wants of the age is not to be expected. Their hold over the men is slowly loosening, but the women still obey, and worship them, and while this subjection lasts Hindu caste and Hindu exclusiveness will remain.

Though not recognised in books, many social grades are found among these fallen Brahmans. Those ministering to the Nava-sakha,1 popularly called Sudra Brahmans, occupy a position of comparative distinction; but at the bottom of the scale Brahmans appear, who are accounted lower than the vile caste they serve; while such an individual as the Chandal, or Dom, Brahman scarcely deserves to be called by that proud title.

The Vaisya caste, standing next the sacred order, occupies a very anomalous and strange position. Their claim to be genuine Vaisyas is admitted by the higher classes, but the Ballali Vaidya and Kayath refuse to touch food prepared by them. This small caste deny that Ballal Sen re-organised, or interfered in anyway with their regulations, and for this reason it remains isolated and unrecognised by Hindus.

The two next castes are the Vaidya and Kayath, who repudiate the name of Sudra, and maintain that Ballal Sen did not enroll them among the "Nava-Sakha." Both are satisfied to rest their title of superiority on the fabulous births of their reputed ancestors. Ballal Sen belonged to the Vaidya caste, and it is to his partiality that it secured pre-eminence. On one section the Brahmanical cord was bestowed, although the caste profession was a dishonourable one, and Ghataks were engaged to preserve the family purity. There has always existed much latent jealousy between the Vaidya and Kayath, but the latter acknowledge some inferiority, although the cause of this difference is never defined.

The Kayath is undoubtedly one of the oldest tribes in Bengal, but it is unnecessary to believe all that is said of Adisura and the five servants of the five Kanaujiya Brahmans. One branch, the Bangaja,2 has been settled for many generations at Edilpur, along with the caste Ghataks, and Kulin Kayath families are as punctilious and as vain of their birth as any Ganguli, or Mukharji, although the Lalas of Mathura and Agra laugh at such pretensions, and will not recognse them as Kayths at all.

The Kevala, or pure Sudra, does not exist in Bengal. All castes below the Brahman belong to the "Varna-Sankara," being the offspring of parents of different tribes.

The recognized authorities on caste are the Institutes of Menu, the Jati Nirnaya chapter of the Brahma-Vaivartta Purana,1 and the Jatimala. According to the Brahmans it was the wickedness of Vena, the Rajarshi, who ordered that no worship should be performed, no oblations offered, and no gifts bestowed on Brahmans, and caused the people to disobey the laws and intermarry with prohibited classes. Until his era Brahmans only married Brahmans, Sudras women of their own rank, and Chandalas followed their own tribal customs.

It was natural for the priests to attribute the irreligious propensities of the people to a cause like this; but there is no doubt that laws prescribed by the Brahmans for maintaining the purity of their order must have been soon violated by those in whose favour they were enacted. Although marriages between individuals of different tribes gave origin to the Varna-Sankara, or mixed castes, the Puranas give other explanations. According to the Brahma-Vaivartta Purana, the gardener, blacksmith, shellcutter, weaver, potter, and brasier are descended from the offspring of Visvakarma, the celestial architect, and Ghritachi, an Apsara, or nymph of heaven, and hence it is that all Karus, or artisans, worship their progenitor with exceptional reverence.

The reasons, again, why certain casts are degraded, are often quite ludicrous, but this does not cause their rejection. The Sutradhara lost rank for refusing to supply the Brahman with sacrificial wood; the Chitrakara for painting execrably; and the Suvarnakara for stealing gold given him to mould an idol. The modern Sunri, moreover, does not resent being told that his ancestor was created from the chips of the mutilated trunk of Ganesa, nor the Kumar that Siv transformed a waterpot into the first potter.

According to the classification of Ballal Sen, as interpreted in Eastern Bengal, the nine following castes are considered pure, and the so called Sudra Brahman officiates for all:�

1 Or Nava-Sayaka, the nine inferior castes.

2 Banga, or Vanga-ja, Bengali born.

1 Literally mixture of colour, hence mixture of castes.

1 A Synopis of this is given in the "Calcutta Review," vol. xv, p. 60.

Judging, however, by traditions still surviving, the position of a caste in the new roll depended chiefly on its usefulness and importance to the community at large. The profession which had proved itself essential to the comfort, or welfare, of the Hindu hierarchy, was at once promoted to a higher level, while the less important was reduced. Thus the Tanti, unclean in Bihar, became clean in Dacca, and the indispensable barber was raised to the same social level as the Kayasth. The relative position of the various castes is still a burning question in Bengal, and in large villages, where any caste predominates, its claims to superior rank are usually conceded. For instance, the Gandha-banik, Teli, Tambuli, and Kansari often assert to good purpose the right of being enrolled among the nine, and, if their voice be sufficiently loud and influential, it will be heard.

The Nava-Sakha have five servants, or Pancha-vartta, attached to them in common, who possess the prescriptive right of attending at all caste and family celebrations. The five servants are the Brahman, Malakar, Dhoba, Napit, and Nata, or musician, who are presumed to be exclusively engaged in the service of the Sudras, but they also earn money by waiting on lower castes. Even now-a-days some work for the Surya-vansi, who ten years ago were not Hindus in name, while others readily work for the Baoti, Kapali, Kawali, Parasara Das, and other tribes of doubtful origin. Where the fisher pastes are numerous, and cannot be overlooked, no difficulty is found in engaging their services. They work indeed for all castes employing a Patit Brahman, but the utterly vile tribes, the Bhuinmali, Chamar, Patni, and Sunri, having Brahmans of their own, are not served by the Pancha-vartta. To this general rule, however, there are exceptions. The worshipful barber, for instance, condescends to shave, but will not pare the nails of the rich Saha merchant.

Although caste is no longer revered as an old institution sanctified by religion and immemorial usage, and is disappearing before the assaults of modern civilisation, a tendency to the formation of new castes still exists. Semi-Hinduized races are being enrolled among Hindus, and old established castes are being split up by adopting new occupations. But if this new occupation be not dishonouring, the Purohit continues his ministration. For instance, the great Chandal tribe has given off eight branches, yet the Chandal Brahman officiates for all. On the other hand, the agricultural Kaibarttas, having taken to a wise employment, are obliged to support a Purohit of their own. Between the Sudras and the Nicha, or vile, castes many tribes, organised by degraded Brahmans, or united by the exigencies of modern civilisation, are found occupying an uncertain position, exposed to the sneers of the exclusive and conservative Sudras.

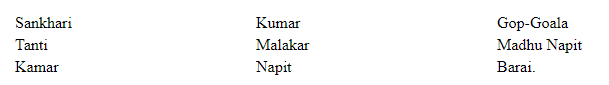

These intermediate castes are :�

In the Tantras,1 the epithet Antya-ja, or inferior, is applied to the following seven tribes, washerman, currier, mimic (Nata), fisherman, "Meda," or attendant on women, cane-splitter (Varuda) and mountaineer (Bhilla). The term Antyavasayin, or dwellers outside the town, was given to the Dom, Pan, Hari, and other sweeper castes.

We however possess a very correct list2 of the outcast tribes in Bengal in the roll of pilgrims excluded from the temple of Jagannath. If prohibited castes are distinguished from professions there are only eleven castes so utterly disreputable that they dare not enter the sanctuary.

These are the Much information regarding caste, as understood in Bengal, is obtained by comparing the relative position of Hindustanis who reside, or temporarily sojourn there, with that of castes native to the province.

Permanent residence is always attended by social expulsion, but a stay of a few years is with some castes a disqualification, with others it is not so. For example, the Ahir, Surahiya, and Kanaujiya Brahmans, who keep up communication with their kindred and marry from their own homes, are reckoned pure but the Kahar, Ahir, and Kandu domiciled in Bengal forfeit all claim to be considered stainless. By adopting local Sudra customs and marrying with women of the country Hindustani tribes are stigmatized as "Khonta,"or debased. The Kanaujiya Brahman, again, expelled by his family for these delinquencies, finds shelter in the ranks of the Srotriya, but above this he cannot expect to rise, and his children mast be content with a very ambiguous position.

The steps by which a Hindustani caste loses its original rank, and gains a new one, may be traced in the case of the potters. The Kumhar of Bihar is always unclean in Bengal, but if he marries a kinswoman he may return to his home without loss of rank. The Raj-Mahallia potters, however, being in an intermediate state, have neither risen to an equality with the Bengali Kumar, nor remained unclean like the Kumhar. The Sudras of Bengal drink from their water vessels, and, still more blessed, the Sudra Brahman ministers unto them. Lastly, the Bengali Kumar, originally of the same stock, has become in the course of ages a pure Sudra, and one of the Nava-Sakha.

In no instance, however, is the separation between kindred castes so striking as with the Chamars and Rishis. Both belong to the same tribe, both are equally vile in the eyes of Hindus, and both live apart from all other castes, yet similar occupations not only excite jealousy and enmity but prevent all friendly intercourse between them.

Occupations, moreover, which a Hindustani may engage in at home without stain or obliquy are sometimes unbecoming when the habitation is in Bengal. Thus the Domni and Chamain, professional musicians in Upper India, are disgraced by plying for hire in Bengal, while on the other hand such menial work as the Mungirya Tantis perform in Daca would be considered very debasing in their own district.

Although continuous residence at a distance usually repels, a brief sojourn sometimes draws together disunited subdivisions. Thus the different branches of Ahirs and Chhatris intermarry in Bengal and lose caste, although debarred from doing so in Hindustan.

The Brahmanical order to which the Purohit belongs is generally a nice test of the rank accorded to a Hindustani caste. Among the lower tribes the Guru belongs either to one of the Dasnami orders, or he is a Vaishnava Bhagat,1 who visits his flock at regular intervals, confirming the old, and teaching the young the rudiments of their faith. Maithila Brahmans, on the other hand, ordinarily act as Purohits to Kurmi, Chhatri, Kandu, Ahir, Chain, and Kewat; but Chhatris are occasionally found with a Sarsut, or Sarasvati, Brahman, and Kurmis and Dosadhs with a Sakadvipa. The Kanaujiya tribe again ministers to Binds, Tantis, and Gadariyas. In the case of the Randa Khatris whose parentage is equivocal, the strange phase is found of a Kanaujiya acting as Purohit, a Srotriya of Bengal as Guru.

1 A corrruption of Sanskrit Bhakta, "the devoted," hence a mendicant.

1 Colebrooke's "Essays" ii, 164.

2 Harington's "Analysis" iii, 213; Hunter's "Orissa" i, 136.

A most important distinction between Hindustani and Bengali castes of similar origin, is the religious belief found among them. It may be said with perfect truth that Vaishnavism, in one or other of its diverse forms, to the exclusion of Saivaism and all other creeds, is the faith professed by the agricultural, artizan, and fisher tribes of Bengal. The worship of Krishna has, for obvious reasons, attracted well nigh all the Goala, and other pastoral tribes of India. The teaching of Chaitanya and his successors has made little progress among Hindustani castes, but the sympathetic creeds of Kabir and Nanak Shah have attracted multitudes of disciples. The Kurmis and Dosadhs especially patronize Kabir; the Kewats, Kumhars, and many Dosadhs enroll themselves under the banner of Nanak.

It is among castes from Northern Bengal, such as the Kandu, Bind, Muriari, and Surahiya, that the followers of the strange Panch Piriya creed are to be met with. Other curious sects, unknown to Bengal, are also found in their ranks. The Tirhutiya Tantis are members of the Buddh Ram communion. Kurmis often profess the doctrines taught by Darya Das, and many Dosadhs those of Tulasi Das. Still more worthy of notice is the existence among them of an old prehistoric cultus. The apotheosis of robber chiefs by Dosadhs, the deification of evil spirits, as Rahu by the Dosadhs, Kasi Baba by Binds, and Madhu Kunwar by Tantis, and the animistic idea endowing with life and personality the destructive energy of the Ganges, are all forms of belief unknown to castes native to Bengal.