Jammu & Kashmir, 1908

(→HC directs hoisting of State flag on buildings , vehicles) |

(→Public works) |

||

| Line 3,348: | Line 3,348: | ||

British Government ; and the State is divided into eight divisions, | British Government ; and the State is divided into eight divisions, | ||

known as Kashmir, Jammu, the Jhelum valley, Gilgit, Udhampur cart- | known as Kashmir, Jammu, the Jhelum valley, Gilgit, Udhampur cart- | ||

| − | road, Palace, Jhelum power, and Jammu irrigation. | + | road, Palace, Jhelum power, and Jammu irrigation. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India |G ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Government |G ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Jammu & Kashmir |G ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 61,000 casual,contractual,daily wage workers engaged since 1994 : Govt === | ||

| + | [http://www.dailyexcelsior.com/61000-casual-contractual-daily-wage-workers-engaged-since-1994-govt/ Daily Excelsior , 61,000 casual,contractual,daily wage workers engaged since 1994 : Govt "Daily Excelsior" 9/10/2015] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Government today stated that 60682 casual, contractual and dailywage workers have been engaged in various departments since April 1994. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a written reply to the questions to five MLCs that include Ali Mohammad Dar, Sham Lal Bhagat, Master Noor Hussain, Ashok Khajuria and Vibodh Gupta, the Finance Minister stated that these workers have been engaged in nearly 30 departments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Government has further stated that no general policy for regularization of such workers has been framed yet. “However, in some departments like Power Development Department and Higher Education Department, there is a provision in applicable service recruitment rules, in terms of which PDL/ TDL are being regularized by the departments themselves,” the Government stated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Government further stated that the Home Department has converted 3,113 Special Police Officers (SPOs) as followers and constables after putting in place various measures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | About whether the Government has framed any policy about the regularization of these dailywagers and whether they are giving any relaxation in certain cases also with special references to over-aged dailywagers, the Finance Ministry stated that no such policy has been framed yet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “However, in order to address the issue, the Government contemplates to constitute a high power Committee to examine the issue and make recommendations,” the Finance Ministry added in its reply | ||

==Army== | ==Army== | ||

Revision as of 01:21, 18 February 2017

Kashmir and Jammu

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Physical aspects

The door is at Jammu, and the house faces south, looking out on the Punjab Districts of Jhelum, Gujrat, Sialkot, and Gurdaspur. There is just a fringe of level land along the Punjab frontier, bordered by a plinth of low hilly country sparsely wooded, broken, and irregular. This is known as the Kandi, the home of the Chibs and the Dogras. Then comes the first storey, to reach which a range of mountains, 8,000 feet high, must be climbed. This is a temperate country with forests of oak, rhododendron, and chestnut, and higher up of deodar and pine, a country of beautiful uplands, such as Bhadarwah and Kishtwar, drained by the deep gorge of the Chenab river. The steps of the Himalayan range known as the Pir Panjal lead to the second storey, on which rests the exquisite valley of Kashmir, drained by the Jhelum river. Up steeper flights of the Himalayas we pass to Astor and Baltistan on the north and to Ladakh on the east, a tract drained by the river Indus. In the back premises, far away to the north-west, lies Gilgit, west and north of the Indus, the whole area shadowed by a wall of giant mountains which run east from the Kilik or Mintaka passes of the Hindu Kush, leading to the Pamirs and the Chinese dominions past Rakaposhi (25,561 feet), along the Muztagh range past K 2 (Godwin Austen, 28,265 feet), Gasherbrum and Masherbrum (28,100 and 25,660 feet respectively) to the Karakoram range which merges in the Kuenlun mountains. Westward of the northern angle above Hunza-Nagar the mighty maze of mountains and glaciers trends a little south of east along the Hindu Kush range bordering Chitral, and so on into the limits of Kafiristan and Afghan territory.

At the Karakoram pass (18,317 feet) the wall zigzags, and to the north-east of the State is a high corner bastion of mountain plains at an elevation of over 17,000 feet, with salt lakes dotted about. Little is known of that bastion ; and the administration of Jammu and Kashmir has but scanty information about the eastern wall of the property, which is formed of mountains of an elevation of about 20,000 feet, and crosses lakes, like Pangkong, lying at a height of nearly 14,000 feet. The southern boundary repeats the same features — grand mountains running to peaks of over 20,000 feet ; but farther west, where the wall dips down more rapidly to the south, the elevation is easier, and we come to Bhadarwah (5,427 feet) and to the still easier heights of Basoli (2,170 feet) on the Ravi river. From Madhopur, the head-works of the Bari Doab Canal, the Ravi river erases tn be the boundary, and a line crossing the (Ujh river and the watershed of the low Dogra hills runs fairly straight to Jammu. A similar line, marked by a double row of trees, runs west from Jammu to the Jhelum river. From the south-west corner of the territories the Jhelum river forms an almost straight boundary on the west as far as its junction with the Kunhar river, 14 miles north of Kohala. At that point the western boundary leaves the river and clings to the moun- tains, running in a fairly regular line to the grand snow scarp of Nanga Parbat (26,182 feet). Thence it runs almost due north to the crossing of the Indus at Ramghat under the Hattu Plr, then north-west, sweep- ing in Punial, Yasln, Ghizar, and Koh, the Mehtarjaos or chiefs of which claim the Tangir and I )arel country, and linking on to the Hindu Kush and Muztagh ranges which look north to Chinese territory and south to Hunza-Nagar and Gilgit.

It is said of the first Maharaja Gulab Singh, the builder of the edifice just described, that when he surveyed his new purchase, the valley of Kashmir, he grumbled and remarked that one-third of the country was mountains, one-third water, and the remainder alienated to privileged persons. Speaking of the whole of his dominions, he might without exaggeration have described them as nothing but mountains. There are valleys, and occasional oases in the deep canons of the mighty rivers ; but mountain is the predominating feature and has strongly affected the history, habits, and agriculture of the people. Journeying along the haphazard paths which skirt the river banks, till the sheer cliff bars the way and the track is forced thousands of feet over the mountain-top, one feels like a child wandering in the narrow and tortuous alleys which surround some old cathedral in England.

It is impossible within the limit of this article to deal in detail with the nooks and corners where men live their hard lives and raise their poor crops in the face of extraordinary difficulties. There are interest- ing tracts like Padar on the southern border, surrounded by perpetual snow, where the edible pine and the deodar flourish, and where the sunshine is scanty and the snow lies long. It was in Padar that were found the valuable sapphires, pronounced by experts the finest in the world. Farther east across the glaciers lies the inaccessible country of Zaskar, said to be rich in copper, where the people and cattle live indoors for six months out of the year, where trees are scarce and food is scarcer. Zaskar has a fine breed of ponies. Farther east is the lofty Rupshu, the lowest point of which is 13,500 feet ; and even at this great height barley ripens, though it often fails in the higher places owing to early snowfall. In Rupshu live the nomad Champas, who are able to work in an air of extraordinary rarity, and complain bitterly of the heat of Leh (1 1,500 feet).

Everywhere on the mass of mountains are places worthy of mention, but the reader will gain a better idea of the country if he follows one or more of the better known routes. A typical route will be that along which the troops sometimes march from Jammu, the winter capital, past the Summer Palace at Srinagar in Kashmir to the distant outpost at Gilgit. The traveller will leave the railway terminus on the south bank of the Tawi, the picturesque river on which Jammu is built. From Jammu (1,200 feet) the road rises gently to Dansal (1,840 feet), passing through a stony country of low hills covered with acacias, then over steeper hills of grey sandstone where vegetation is very scarce, over the Laru Lari pass (8,200 feet), dropping down again to 5,150 feet and lower still to Ramban (2,535 feet), where the Chenab river is crossed, then steadily up till the Banihal pass (9,230 feet) is gained and the valley of Kashmir lies below.

So far the country has been broken, and the track devious, with interminable ridges, and for the most part, if we except the vale of the Bichlari, the pine woods of Chineni, and the slopes between Ramban and Deogol (Banihal), a mere series of flat uninteresting valleys, unrelieved by forests. It is a pleasure to pass from the scenery of the outer hills into the green fertile valley of Kashmir — the emerald set in pearls. The valley is surrounded by mountain ranges which rise to a height of 18,000 feet on the north-east, and until the end of May and sometimes by the beginning of October there is a continuous ring of snow around the oval plain. Leaving the Banihal pass — and no experienced traveller cares to linger on that uncertain home of the winds — the track rapidly descends to Vernag (6,000 feet), where a noble spring of deep-blue water issues from the base of a high scarp. This spring may be regarded as the source of Kashmir's great river and waterway, commonly known as the Jhelum, the Hydaspes of the ancients, the Vitasta in Sanskrit, and spoken of by the Kashmiris as the Veth. Fifteen miles north the river becomes navigable ; and the traveller, after a march of no miles, embarks at Khanabal in a fiat-bot- tomed boat and drops gently down to Srinagar, the capital of Kashmir.

Looking at a map of Kashmir, one sees a white footprint set in a mass of black mountains. This is the celebrated valley, perched securely among the Himalayas at an average height of 6,000 feet above the sea. It is approximately 84 miles in length and 20 to 25 miles in breadth. North, east, and west, range after range of mountains guard the valley from the outer world, while in the south it is cut off from the Punjab by rocky barriers, 50 to 75 miles in width. The mountain snows feed the river and the streams, and it is calculated that the Jhelum in its course through the valley has a catchment area of nearly 4,000 square miles. The mountains which surround Kashmir are infinitely varied in form and colour. To the north lies a veritable sea of mountains broken into white-crested waves, hastening away in wild confusion to the great promontory of Nanga Parbat (26,182 feet). To the cast stands Haramukh (16,903 feet), the grim mountain which guards the valley of the Sind. Farther south is Mahadeo, very sacred to the Hindus, which seems almost to look down upon Snnagar ; and south again are the lofty range of Gwash Brari (17,800 feet), and the peak of Amarnath (17,321 feet), the mountain of the pilgrims and very beautiful in the evening sun. On the south-west is the Panjal range with peaks of r 5,000 feet, over which the old imperial road of the Mughals passes ; farther north the great rolling downs of the Tosh Maidan (14,000 feet), over which men travel to the Punch country; and in the north-west corner rises the Kajinag (12,125 feet), the home of the mdrkhor.

On the west, and wherever the mountain-sides are sheltered from the hot breezes of the Punjab plains, which blow across the intervening mountains, there are grand forests of pines and firs. Down the tree- clad slopes dash mountain streams white with foam, passing in their course through pools of the purest cobalt. When the great dark forests cease and the brighter woodland begins, the banks of the streams are ablaze with clematis, honeysuckle, jasmine, and wild roses which remind one of azaleas. The green smooth turf of the woodland glades is like a well-kept lawn, dotted with clumps of hawthorn and other beautiful trees and bushes. It would be difficult to describe the colours that are seen on the Kashmir mountains. In early morning they are often a delicate semi-transparent violet relieved against a saffron sky, and with light vapours clinging round their crests. The rising sun deepens the shadows, and produces sharp outlines and strong passages of purple and indigo in the deep ravines. Later on it is nearly all blue and lavender, with white snow peaks and ridges under a vertical sun ; and as the afternoon wears on these become richer violet and pale bronze, gradually changing to rose and pink with yellow or orange snow, till the last rays of the sun have gone, leaving the mountains dyed a ruddy crimson, with the snows showing a pale creamy green by contrast. Looking downward from the mountains the valley in the sunshine has the hues of the opal ; the pale reds of the karezvas, the vivid light greens of the young rice, and the darker shades of the groves of trees relieved by sunlight sheets, gleams of water, and soft blue haze give a combination of tints reminding one irresistibly of the changing hues of that gem. It is impossible in the scope of this article to do justice to the beauty and grandeur of the mountains of Kashmir, or to enumerate the lovely glades and forests, visited by so few. Much has been written of the magnificent scenery of the Sind and Liddar valleys, and of the gentler charms of the Lolab, but the equal beauties of the western side of Kashmir have hardly been described. Few countries can offer anything grander than the deep-green mountain tarn, Konsanag, in the Panjal range, the waters of which make a wild entrance into the valley over the splendid cataract of Arabal, while the rolling grass mountain called Tosh Maidan, the springy downs of Raiyar looking over the Suknag river as it twines, foaming down from the mountains, the long winding park known as Yusumarg, and lower down still the little hills which remind one of Surrey, and Nilnag with its pretty lake screened by the dense forests, are worthy to be seen.

As one descends the mountains and leaves the woodland glades, cul- tivation commences immediately, and right up to the fringe of the forests maize is grown and walnut-trees abound. A little lower down, at an elevation of about 7,000 feet, rice of a hardy and stunted growth is found, and the shady plane-tree appears. Lower still superior rices are grown, and the watercourses are edged with willows. The side valleys which lead off from the vale of Kashmir, though possessing dis- tinctive charms of their own, have certain features in common. At the mouth of the valley lies the wide delta of fertile soil on which the rice with its varying colours, the plane-trees, mulberries, and willows grow luxuriantly ; a little higher up the land is terraced and rice still grows, and the slopes are ablaze with the wild indigo, till at about 6,000 feet the plane-tree gives place to the walnut, and rice to millets. On the left bank of the mountain river endless forests stretch from the bottom of the valley to the peaks ; and on the right bank, wherever a nook or corner is sheltered from the sun and the hot breezes of India, the pines and firs establish themselves. Farther up the valley, the river, already a roaring torrent, becomes a veritable waterfall dashing down between lofty cliffs, whose bases are fringed with maples and horse-chestnuts, white and pink, and millets are replaced by buckwheat and Tibetan barley. Soon after this the useful birch-tree appears, and then come grass and glaciers, the country of the shepherds.

Where the mountains cease to be steep, fan-like projections with flat arid tops and bare of trees run out towards the valley. These are known as kareivas. Sometimes they stand up isolated in the middle of the valley, but, whether isolated or attached to the mountains, the kareivas present the same sterile appearance and offer the same abrupt walls to the valley. The karewas are pierced by mountain torrents and seamed with ravines. Bearing in mind that Kashmir was once a lake, which dried up when nature afforded an outlet at Baramula, it is easy to recognize in the kareivas the shelving shores of a great inland sea, and to realize that the inhabitants of the old cities, the traces of which can be seen on high bluffs and on the slope of the mountains, had no other choice of sites, since in those days the present fertile valley was buried beneath a waste of water.

Kashmir abounds in mountain tarns, lovely lakes, and swampy lagoons. Of the lakes the Wular, the Dal, and the Manasbal are the most beautiful. It is also rich in springs, many of which are thermal. They are useful auxiliaries to the mountain streams in irrigation, and are sometimes the sole sources of water, as in the case of Achabal, Vernag, and Kokarnag on the south, and Arpal on the east. Islamabad or Anantnag, ' the place of the countless springs,' sends out numerous streams. One of these springs, the Maliknag, is sulphurous, and its water is highly prized for garden cultivation. The Kashmiris are good judges of water. They regard Kokarnag as the best source of drinking-water, while Chashma Shahi above the Dal Lake stands high in order of merit. It is time now for the traveller who has been resting in Srinagar to set out on the great northern road which leads to Gilgit. He will have admired the quaint, insanitary city lying along the banks of the Jhelum, with a length of 3 miles and an average breadth of i£ miles on either side of the river. The houses vary in size from the large and spacious brick palaces of the Pandit aristocrat and his 500 retainers, warmed in the winter by hammams, to the doll house of three storeys, where the poor shawl-weaver lives his cramped life, and shivers in the frosty weather behind lattice windows covered with paper. In the spring and summer the earthen roofs of the houses, resting on layers of birch-bark, are bright with green herbage and flowers. The canals with their curious stone bridges and shady waterway, and the great river with an average width of eighty yards, spanned by wooden bridges, crowded with boats of every description, and lined by bathing boxes, are well worth studying. The wooden bridges are cheap, effective, and pictur- esque, and their construction is ingenious, for in design they appear to have anticipated the modern cantilever principle. Old boats filled with stones were sunk at the sites chosen for pier foundations. Piles were then driven and more boats were sunk. When a height above the low- water level was reached, wooden trestles of deodar were constructed by placing rough-hewn logs at right angles. As the structure approached the requisite elevation to admit of chakivdris (house-boats) passing be- neath, deodar logs were cantilevered. This reduced the span, and huge trees were made to serve as girders to support the roadway.

The foun-

dations of loose stones and piles have been protected on the upstream

side by planking, and a rough but effective cut-water made. The secret

of the stability of these old bridges may, perhaps, be attributed to the

skeleton piers offering little or no resistance to the large volume of water

brought down at flood-time. It is true that the heavy floods of 1893

swept away six out of the seven city bridges, and that the cumbrous

piers tend to narrow the waterway, but it should be remembered that

the old bridges had weathered many a serious flood. Not long ago two

of the bridges, the Habba Kadal and the Zaina Kadal, had rows of

shops on them reminding one of Old London Bridge ; but these have

now been cleared away.

The distance by road from Srinagar to Gilgit is 228 miles, and the

traveller can reach Bandipura at the head of the Wular Lake by boat or

by land. The Gilgit road, which cost the Kashmir State, in the first

instance, 15 lakhs, is a remarkable achievement, and was one of the

greatest boons ever conferred on the Kashmiri subjects of the Maharaja.

Previous to its construction supplies for the Gilgit garrison were carried

by impressed labourers, many of whom perished on the passes, or

returned crippled and maimed by frost-bite on the snow or accident on

the goat paths that did duty for roads. The journey to Gilgit before

1890 has been aptly compared with the journey to Siberia. Now, sup-

plies are carried on ponies and the name Gilgit is no longer a terror to

the people of Kashmir.

From Bandipura a steep ascent leads to the Raj Diangan pass (1 1,800 feet), a most dreaded place in the winter months, when the cold winds mean death to man and beast. Thence through a beautifully wooded and watered country, past the lovely valley of Gurais, down which the Kishanganga flows, the traveller has no difficulties till he reaches the Burzil pass (13,500 feet), below which the summer road to Skardu across the dreary wastes of the Deosai plains branches off to the north- east. This is a very easy pass in summer, but is very dangerous in a snowstorm or high wind.

Descending from the Burzil the whole scene changes. The forests and vegetation of Kashmir are left behind, the trees are few and of a strange appearance, and the very flowers look foreign. It is a bleak and rugged country, and when Astor (7,853 feet) is left the sense of desola- tion increases. Nothing can be more dreary than the steep descent from Doian down the side of the arid Hattu Fir into the sterile waste of the Indus valley. It is cool at Doian (8,720 feet); it is stifling at Ram- ghat (3,800 feet), where one passes over the Astor river by a suspension bridge. The old construction was a veritable bridge of sighs to the Kashmir convicts who were forced across the river and left to their fate ■ — starvation or capture by the slave-hunters from Chilas. A little cultivation at Bunji relieves the eye ; but there is nothing to cheer the traveller until the Indus has been crossed by a fine bridge, and 30 miles farther the pleasant oasis of Gilgit is reached.

The Indus valley is a barren dewless country. The very river with its black water looks hot, and the great mountains are destitute of vegetation. The only thing of beauty is the view of the snowy ranges, and Nanga Parbat in the rising sun seen from the crossing of the Indus river to Gilgit sweeps into oblivion the dreadful desert of sands and rock. Gilgit (4,890 feet) itself is fertile and well watered. The moun- tains fall back from the river, and leave room for cultivation on the alluvial land bordering the right bank of the Gilgit river, a rare feature in the northern parts of the Maharaja's dominion.

Another route giving a general idea of the country runs from west to east, from Kohala on the Jhelum to Leh, about 5 miles beyond the Indus. A good road from Rawalpindi brings the traveller to Kohala, where he crosses the Jhelum by a bridge, and enters the territories of Tammu and Kashmir. The cart-road passes from Kohala to Srinagar, a distance of 132 miles, by easy gradients. As far as Baramula the road is close to the river, but for the most part at a great height above it, and the scenery is beautiful. At Muzaffarabad the Kishanganga river joins the Jhelum, and here the road from Abbottabad and Garhi Hablb-ullah connects with the Kashmir route. The road runs along the left bank of the Jhelum, through careful terraced cultivation, above which are pine forests and pastures. It carries a very heavy traffic, but owing to the formation of the country it is liable to constant breaches, and is expensive to keep in repair.

From Uri a road runs south to the country of the Raja of Punch, the chief feudatory of the Maharaja, crossing the Haji pass (8,500 feet). At Baramula the road enters the valley of Kashmir, and runs through a continuous avenue of poplars to Srinagar. In bygone days this route, known as the Jhelum valley road — now the chief means of communica- tion with India — was little used. The Bambas and Khakhas, who still hold the country, were a restless and warlike people ; and the numerous forts that command the narrow valley suggest that the neighbourhood was unsafe for the ordinary traveller. The construction of the road from Kohala to Baramula cost the State nearly 22 lakhs.

From Srinagar to Leh is 243 miles. The first part of the journey runs up the Sind valley, perhaps the most exquisite scenery in Kashmir. Fitful efforts are made from time to time to improve this important route, but it still remains a mere fair-weather track. The Sind river thunders down the valley, and the steep mountains rise on either side, the northern slopes covered with pine forest, the southern bare and treeless. At Gagangir the track climbs along the river torrent to Sonamarg (8,650 feet), the last and highest village in the Sind valley, if we except the small hamlet of Nilagrar some 2 miles higher up. Sonamarg is a beautiful mountain meadow surrounded by glaciers and forests. It is a miserable place in the winter time, but it is of great importance to encourage a resident population. The chief staples of cultivation are grim, or Tibetan barley, and buckwheat. It is good to turn loose the baggage ponies to graze on the meadow grasses ; for in a few more marches one passes into a region like the country beyond the Burzil on the road to Gilgit, a land devoid of forests and pastures, 'a desert of bare crags and granite dust, a cloudless region always burn- ing or freezing under the clear blue sky.' The Zoji La (1 1,300 feet) is the lowest depression in the great Western Himalayas which run from the Indus valley on the Chilas frontier. Over this high range the rains from the south hardly penetrate, and the cultivation, scanty and diffi- cult, depends entirely on artificial canals. The ascent to the Zoji La from Kashmir is very steep, the descent to the elevated table-land of Tibet almost imperceptible. For five marches the route follows the course of the Dras river, through a desolate country of piled up rocks and loose gravel. At Chanagund the road to Skardu crosses the Dras river by a cantilever bridge, 4 miles above the junction of the Dras and Suru rivers, and about 8 miles farther on the Indus receives their waters. But the steep cliffs of the Indus offer no path to the traveller, and the track leaves the Dras river, and turns in a southerly direction to Kargil, a delightful oasis.

Then the road abandons the valleys and

ascends the bare mountains. The dreary scenery is compensated by

the cloudless pale blue sky and the dry bracing air so characteristic of

Ladakh. Through gorges and defiles the valley of Shergol is reached)

the first Buddhist village on the road. Thenceforward the country is

Buddhist, and the road runs up and down over the Namika La ( 1 3,000 feet)

and over the Fotu La (13,400 feet), the highest point on the Leh road.

Along the road near the villages are Buddhist monasteries, mam's (walls

of praying stones) and chortens, where the ashes of the dead mixed with

clay and moulded into a little idol are placed, and at Lamayaru there

is a wilderness of monuments. Later, the Indus is crossed by a long

cantilever bridge ; and the road runs along the right bank through the

fertile oasis of Khalsi, then through the usual desert with an occasional

patch of vegetation to Leh (11,500 feet), the capital of Western Tibet

and of Western Buddhism, and the trade terminus for caravans from

India and from Central Asia. It is a long and difficult road from Leh

to Yarkand, 482 miles, over the Khardung La, the Sasser La, and the

Karakoram pass of between 17,000 and 19,000 feet altitude, where the

useful yak (Bos grunniens) relieves the ponies of their loads when fresh

snow has fallen, or serves unladen to consolidate a path for the ponies.

A brief description may be given of one more of the many routes

that follow the rivers and climb the mountains — the route from Leh

through Baltistan to Astor on the Gilgit road. At Khalsi, where the

Srlnagar-Leh road crosses the Indus, the track keeps to the right bank

of the Indus, and passing down the deep gorge of the river comes to

a point where the stupendous cliffs and the roaring torrent prevent

farther progress. There the traveller strikes away from the Indus and

ascends the mountains to the Chorbat pass (16,700 feet), covered with

snow even in July. From the pass, across the valley of the Shyok river,

the great Karakoram range, some 50 miles away, comes into view. An

abrupt descent carries the traveller from winter into hot summer ; and

by a difficult track which in places is carried along the face of the cliff

by frail scaffolding (pari), following the course of the Shyok river,

smoothly flowing between white sands of granite, and passing many

pleasant oases, one comes to the grateful garden of Khapallu, a paradise

to the simple Baltis. Crossing the united waters of the Shyok and the

Indus on a small skin raft, the traveller arrives at Skardu (7,250 feet),

the old capital of Baltistan.

Here the mountains on either side of the

Indus recede, and the sandy basin, about 5 miles in breadth, is partially

irrigated by water from the pretty mountain lake of Satpura and care-

fully cultivated. Looking across the Indus to the north, the Shigar

valley, the garden of Baltistan, with its wealth of fruit trees is seen.

There the cultivator adds to his resources by washing gold from the

sands of the river. From Skardu the direct route to (lilgit follows the

Indus, which is crossed at Rondu by a rope bridge so long as to be

most trying to the nerves, but a fair-weather track over the Banak pass

lands the traveller on the Gilgit road at Astor.

It is difficult to give a general idea of a country so diversified as Kashmir and Jammu. As will be seen in the section on History, a strange destiny has brought people of distinct races, languages, and religions, and countries of widely different physical characteristics, under the rule of the Maharaja.

The Kashmir territory may be divided physically into two areas : the north-eastern, comprising the area drained by the Indus with its tribu- taries ; and the south-western, including the country drained by the Jhelum with its tributary the Kishanganga, and by the Chenab. The dividing line or watershed is formed by the great central mountain range which runs from Nanga Parbat, overhanging the Indus on the north- west, in a south-easterly direction for about 240 miles till it enters British territory in Lahul.

The south-western area may, following the nomenclature of Mr. Drew, in its turn be geographically divided into three sections : the region of the outer hills, the middle mountains, and the Kashmir Valley. Approaching Kashmir from the plains of the Punjab, the boundary is not at the foot of the hills, but embraces a strip of the great plains from 5 to 15 miles wide, reaching from the Ravi to the Jhelum. As is generally the case along the foot of the Western Himalayas, this tract of flat country is somewhat arid and considerably cut up by ravines which carry off the flood-water of the monsoon. A fair amount of cul- tivation is found on the plateaux between these ravines, though, being entirely dependent on the rainfall, the yield is somewhat precarious. The height of this tract may be taken at from 1,100 to 1,200 feet above sea-level.

Passing over the plain a region of broken ground and low hills is reached, running mainly in ridges parallel to the general line of the Himalayan chain. These vary in height from 2,000 to 4,000 feet, and are largely composed of sandstone, being in fact a continuation of the Siwalik geological formation. Lying between these parallel ridges are a series of valleys or duns, fairly well populated, in the east by Dogras and in the west by Chibs. These hills are sparsely covered with low scrub bushes, the chlr (Pinus longifolia) gradually predominating as the inner hills are reached. Beyond these lower hills rise the spurs of a more mountainous district.

The scope of this region, as defined by Mr. Drew, has been some- what extended, and includes the range which forms the southern boundary of the Kashmir Valley, known as the Panjal range, and its continuation eastwards beyond the Chenab. This tract is about 1 80 miles long and varies in width from 25 to 35 miles. The portion lying between the Jhelum and Chenab is formed by the mass of moun- tainous spurs running down from the high Panjal range which forms its northern limit. The Panjal itself, extending from Muzaffarabad on the Jhelum to near Kishtwar on the Chenab, is a massive mountain range, the highest central portion to which the name is truly applied having a length of 80 miles, with peaks rising to 14,000 and 15,000 feet. From the southern side a series of spurs branch out, which break up the ground into an intricate mountain mass cut into by ravines or divided by narrow valleys.

The elevation of these middle mountains is sufficient to give a thoroughly temperate character to the vegetation. Forests of Hima- layan oak, pine, spruce, silver fir, and deodar occupy a great part of the mountain slopes ; the rest, the more sunny parts, where forest trees do not flourish, is, except where rocks jut out, well covered with herbage, with plants and flowers that resemble those of Central or Southern Europe. East of the Chenab river rises a somewhat similar mass of hills, forming the district of Bhadarwah, with peaks varying from 9,000 to 14,000 feet in height. These culminate in the high range which forms the Chamba and Ravi watershed in Chamba territory.

The third section of the south-western area bears a unique char- acter in the Himalayas, consisting of an open valley of considerable extent completely surrounded by mountains. The boundaries are formed on the north-east by the great central range which separates the Jhelum and Indus drainage, and on the south by the Panjal range already described. The eastern boundary is formed by a high spur of the main range, which branching off at about 75 30' E. runs nearly due south, its peaks maintaining an elevation of from 12,000 to 14,000 feet. This minor range forms the watershed between the Jhelum and Chenab, separating the Kashmir from the Wardwan valley. It eventually joins and blends with the Panjal range about 16 miles west of Kishtwar. On the north and west, the bounding ranges of the valley are more difficult to describe. A few miles west of the spot from which the eastern boundary spur branches near the Zoji La, another minor range is given off. This runs nearly due west for about 1oo miles at an elevation of from 12,000 to 13,000 feet, with a width of from 15 to 20 miles. It forms the watershed between the Jhelum on the south and its important tributary the Kishanganga on the north. After reaching 74 degree 15' E. the ridge gradually curves round to the south, until it reaches the Jhelum abreast of the western end of the Panjal range. The valley thus enclosed has a length, measured from ridge to ridge, of about 115 miles with a width varying from 45 to 70 miles, and is drained throughout by the Jhelum with its various tributaries. The flat portion is much restricted, owing to the spurs given off by the great central range, which run down into the plain, forming the well-known Sind and Liddar valleys. On the southern side the spurs from the Panjal range project 10 to 16 miles into the plain.

The north-eastern section is comprised between the great central chain on the south and the Karakoram range and its continuation on the north. It is drained by the Indus and its great tributaries, the Shyok, the Zaskar, the Sum, and the Gilgit rivers. The chief charac- teristic of this region, more especially of the eastern portion, is the great altitude of the valleys and plains. The junction of the Gilgit and Indus rivers is 4,300 feet above sea-level. Proceeding upstream, 80 miles farther east at the confluence of the Shyok and Indus, the level of the latter is 7,700 feet; opposite Leh, 130 miles farther up the river, its height is 10,600 feet, while near the Kashmir-Tibet boundary in the Kokzhung district the river runs at the great height of 13,800 feet above sea-level.

Between the various streams which drain the country rise ranges of mountains, those in the central portions attaining an elevation of 16,000 to 20,000 feet, while the mighty flanking masses of the Kara- koram culminate in the great peak Godwin Austen (28,265 feet)- The difference of the level in the valleys between the eastern and western tracts has its natural effect on the scenery. In the east, as in the Rupshu district of Ladakh, the lowest ground is 13,500 feet above the sea, while the mountains run very evenly to a height of 20, coo or 21,000 feet. The result is a series of long open valleys, bounded by comparatively low hills having very little of the characteristics of what is generally termed a mountainous country. To the west as the valleys deepen, while the bordering mountains keep at much the same eleva- tion, the character of the country changes, and assumes the more familiar Himalayan character of massive ridges and spurs falling steeply into the deep valleys between.

The central chain commences in the west at the great mountain mass rising directly above the Indus, of which the culminating peak is Nanga Parbat. From this point it runs in a south-easterly direction, forming the watershed between the Indus and the Kishanganga. It quickly falls to an altitude of 14,000 to 15,000 feet, at which it con- tinues for 50 or 60 miles. It is crossed by several passes, the best known of which are the Burzil on the road from Kashmir to Gilgit, and the Zoji La of 11,300 feet, over which runs the road from Srinagar to Dras and Leh. From the Zoji La the mountains rapidly rise in elevation, the peaks attaining an altitude of 18,000 to 20,000 feet, culminating in the Nun Kun peaks which rise to a height of over 23,000 feet. Owing to their altitude these mountains are under per- petual snow, and glaciers form in every valley. The range keeps this character throughout Kashmir territory for a distance of 150 miles to the Bara Lacha (pass), where it passes into Spiti.

The Karakoram range is of a far more complicated character. Broadly speaking, it is a continuation of the Hindu Kush, and forms the watershed between the Central Asian drainage and the streams flowing into the Indian Ocean. From its main ridge lofty spurs extend into Kashmir, separating the various tributaries of the Indus, the result being a stupendous mountain mass 220 miles long, with a width on the south side of the watershed of 30 to 60 miles, with peaks averaging from 21,000 to 23,000 feet, culminating on the west in the well-known Rakaposhi mountain, north of Gilgit, over 25,500 feet high, and in the mighty group of peaks round the head of the Baltoro glacier dominated by the second highest mountain in the world, Godwin Austen, whose summit is 28,265 f eet above the sea. The head of every valley is the birthplace of a glacier. Many of these are of immense size, such as the Baltoro, the Biafo, and Hispar glaciers, the two latter forming an unbroken stretch of ice over 50 miles long. This great mountain barrier is broken through at one point by the Hunza stream, a tributary of the Gilgit river, the watershed at the head of which has the com- paratively low elevation of about 15,500 feet. The next well-known pass lies 150 miles to the east, where the road from Leh to Yarkand leads over the Karakoram pass at an altitude of about 18,300 feet.

A description of this mountainous region would be incomplete with- out a reference to the vast elevated plains of Lingzhithang, which lie at the extreme north-eastern limit of Kashmir territory. These plains are geographically allied to the great Tibetan plateau. The ground- level is from 16,000 to 17,000 feet above the sea, and such rain as falls drains into a series of salt lakes. Of vegetation there is little or none, the country being a desolate expanse of earth and rock. The northern border of this plateau is formed by the Kuenlun mountains, the northern face of which slopes down into the plains of Khotan.

An account of the geology will be found in the memoir by Mr. R. Lydekker, The Geology of tlie Kashmir and Chamha Territories and the British District of Khagan. Mr. Lydekker differs from Mr. Drew, also an expert in geology, who held that some of the gravels at Baramula were of glacial origin, indicating the existence of glaciers in the valley at a level of 5,000 feet ; but he has no doubts as to their existence on the Plr Panjal range and in the neighbourhood of the various margs or mountain meadows which surround the valley. The question of the glaciation and the evidences of relative changes of level within a geologically recent period is fully discussed for the Sind valley by Mr. R. I). Oldham in Eecords, Geological Survey of India, vol. xxxii, part ii.

There is abundant evidence that igneous or volcanic agencies were actively at work, as is proved by the outpouring of vast quantities of volcanic rocks ; but these are not known to have been erupted since the eocene period. Subterraneous thermal action is, however, indicated by the prevalence of numerous hot springs. The burning fields at Soiyam, of which an account is given by Sir W. Lawrence, Valley of Kashmir , pp. 42-3, point to the same conclusion, and the frequency of earthquakes suggests subterranean instability in this area.

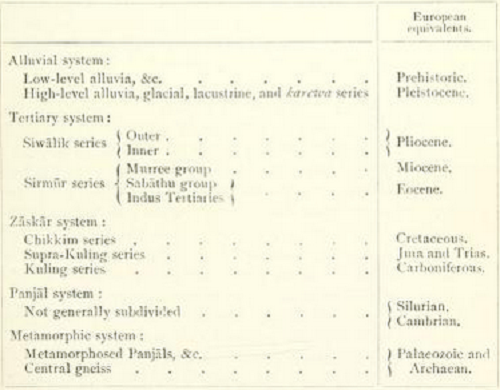

The following table of geological systems in descending order is given by Mr. Lydekker for the whole State: —

Under the first of these systems, Mr. Lydekker has discussed the

interesting question, whether Kashmir was once covered by a great

lake. In this discussion the karewas already described play an impor-

tant part, and the only explanation of the upper karewas is that

Kashmir was formerly occupied by a vast lake of which the existing

lakes are remnants. Mr. Drew estimated that at one period this lake

must have reached a level of nearly 2,000 feet above the present

height of the valley, but this estimate is considered far too high by

Mr. Lydekker. No very satisfactory conclusions can be drawn at

present as to the barrier which dammed the old lake, or as to the

relative period of its existence.

A full account of the flora of Kashmir is given by Lawrence, Valley of Kashmir, chap. iv. The valley has an enormous variety of plants, and the Kashmiri finds a use for most of them. Among condiments the most important is the zlra siyah (Canon sp.), or carraway. Under drugs, Cannabis saliva, the hemp plant, and Artemisia or telivan may be mentioned. Asafoetida is found in the Astor tahsil. Numerous plants yield dyes and tans, of which Datisca cannabina, Rubia cordifolia, and Geranium nepalense are the most familiar. Kashmir is rich in fibres, and the people make great use of them. The two best are the Abutilon Avicennae and the Cannabis saliva. Burza (Betula i/tilis), the paper birch, is a most important tree to the natives. The bark is employed for various purposes, such as roofs of houses, writing paper, and packing paper. Many of the ancient manuscripts are written on birch bark. The Kashmiri neglects nothing which can be eaten as fodder. The willow, the Indian chestnut, the cotoneaster, the hawthorn, and the poplar are always lopped to provide fodder for cattle and sheep in the winter.

Excellent grasses abound, and the swamps yield most nutritious reeds and other plants. There is an abundance of food-plants, too numerous to be enumerated here. Eitryale ferox, JVymp/iaea steliata, JV. alba, Xelumbium speciosum, the exquisite pink water-lily, Acorns Calamus, and Typha sp., the reed mace, all contribute to the Kashmiri's sustenance. Wild fruits are in profusion, and many fungi are eaten by the people. The mushroom is common, and the morel (Morchella sp.) abounds in the mountains and forms an important export to India. There are plants that are useful for hair-washes, and the herbs with medicinal properties are almost innumerable. Macrotomia Benthami is one of these peculiarly esteemed by the Kashmiris as a remedy for heart-affections. Among the scents may be noted Gogal dhup (Jurinea macrocephala), which is largely exported to India, where it is used by Hindus. The most important of the aromatic plants is the Saussurea Lappa. This grows at high elevations from 8,000 to 9,000 feet. The root has a scent like orris with a blend of violet. It is largely exported to China, where it is used as incense in the joss houses. It has many valuable properties, and is a source of considerable revenue to the State. There is a great variety of trees, but the oak, the holly, and the Himalayan rhododendron are unknown. Among the long list of trees may be noticed the deodar, the blue pine, the spruce, the silver fir, the yew, the walnut, and the Indian horse-chestnut.

In the valley itself the exquisite plane-tree, the mulberry, the apricot,

and the willow are perhaps the most familiar.

Kashmir offers great attraction to the sportsman, and for its size the

valley and the surrounding mountains possess a large and varied animal

kingdom. A full account of the animals and birds will be found in

The J'li/ley of Kashmir, chap. v. Since that book was written game

preservation has made great strides, and has prevented the extinction

of the bdrasingha [Cervus duvauceli) and the hangal or Kashmir stag

(C. cashmirianui). Among the Cervidae, the musk deer {Moschus

moschiferus) is common and its pod is valuable. Of the family Ursidae,

the black bear, or bomba hapat (Ursus torquatus), is very common,

being a great pest to the crops and a danger to the people. The

brown bear, or lal hapat ( Ursus arctus or isabellinus), is still far from

rare. It is partly herbivorous and partly carnivorous. Of the family

Bovidae, the markhor (Capra falconeri) and the ibex (C. sibiricd) are

still to be met with. The Kashmir markhor has from one to two com-

plete turns in the spirals of its horns. The tahr or jagla (Hemitragus)

is found on the Plr Panjal, and the serow or rami/ {Nemorhaedus

bubalinus) is fairly common. The goral (Cemas gora/) also occurs.

There is a considerable variety of birds. The blue heron {Ardea cinerea) is very common, and fine heronries exist at several places. The heron's feathers are much valued, and the right to collect the feathers is farmed out. Among game-birds may be noticed the snow partridge {Lenva lerzva), the Himalayan snow cock {Tetraogal/its himalayensis), the chikor partridge (Caccabis chukar), the large grey quail (Cofurm'x), the monal pheasant (Lophophon/s refu/gens), the Simla horned pheasant (Tragopau melanocephalum) % and the Kashmir Pucras pheasant {Pucrasin biddulphi). The large sand-grouse (Pteroc/es aren- arius) is occasionally seen. Pigeons, turtle-doves, rails, grebes, gulls, plovers, snipe, cranes, are common, and storks are sometimes seen. Geese are found in vast flocks on the Wular Lake in the winter, and there are at least thirteen kinds of duck. The goosander and smew are also found on the Wular Lake. There are six species of eagles, four of falcons, and four of owls. Kingfishers, hoopoes, bee-eaters, night-jars, swifts, cuckoos, woodpeckers, parrots, crows in great variety, choughs, starlings, orioles, finches (12 species), buntings, larks, wag- tails, creepers, tits, shrikes, warblers (14 species), thrushes (20 species), dippers, wrens, babbling thrushes, bulbuls, fly-catchers, and swallows are all familiar birds.

Among the reptiles there are two poisonous snakes, the gunas and ihe pohio; the bite of which is often fatal. Fish forms an important item in the food of the Kashmiris. Yigne noticed only six different kinds, but Lawrence enumerated thirteen. As the elevation varies from 1,200 feet at Jammu and 3,000 in the Indus valley at Bunji and Chilas to 25,000 and 26,000 feet on the highest mountain peaks, the State presents an extraordinary variety of climatic conditions. The local variations of temperature depend chiefly upon situation (i.e. whether in a valley or on the crest of a mountain range), elevation, and the amount of the winter snowfall and the period and depth of the snow accumulation. The effect of position in a valley or a mountain crest is shown by comparing the temperatures of Murree and Srinagar. The Murree observatory is about 1,200 feet higher than the Srinagar observatory. The mean maximum day temperature in January at Murree is 7 higher than at Srinagar, and the mean minimum night temperature 9 higher. On the other hand, in the hottest month (June) the maximum day temperature is i° lower at Murree than at Srinagar, while the minimum night temperatures are almost identical. The diurnal range is 2° less in January, 7 less in June, and 14 less in October at Murree than at Srinagar. The slow movement of the air from the higher elevations into valleys more or less completely shut in by mountains tends to depress temperature at valley stations both by day and night considerably below that at similar elevations on the crest of the Outer Himalayas, and to increase the diurnal range most largely in the dry clear months of October and November, when the sinking down of the air from the adjacent mountains has its greatest effect, and is supplemented by rapid radiation from the ground.

The effect of

snow accumulation in valleys in reducing temperature is very marked.

At Dras and Sonamarg, where the accumulation is usually large, the

solar heat on clear fine days in winter is utilized in melting the snow

and hence exercises no influence on the air temperature. At Leh,

where the ground is only occasionally concealed under a thin covering

of snow, the sun even in winter usually warms the ground surface

directly and thence the air. The cooling influence of snow accumula-

tion at Dras and Sonamarg is largely increased by the rapid radiation

from the surface. The mean daily temperature is lowest in January

and highest in June or July. At Srinagar the mean temperature of

January is 33- 1°. The mean temperature of the hottest month (July)

at Srinagar is 74-6°. The mean temperature in January and August

ranges from 25-3° to 75 at Skardu, from 3-4° to 64-5° at Dras, from

17-7° to 61. 8° at Leh, and from 36-6° to 85° (in July) at Gilgit. The

most noteworthy features of the annual variation are the very rapid

increase in March or April at the end of the winter, and an equally

rapid decrease in October, when the skies clear after the south-west

monsoon. The diurnal range is least at Gilgit (IO-8 ) and Srinagar

(22-4°) on the mean of the year, and greatest at Dras (31-4°) and

Leh (26-3°).

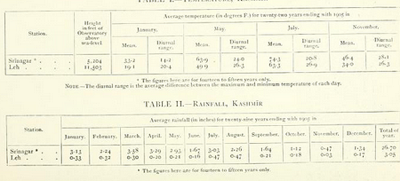

The precipitation is received during two periods, the cold season from December to April, and the south-west monsoon period from June to September. The rainfall in October and November is small in amount, and November is usually the driest month of the year. The cold-season precipitation from December to March is chiefly due to storms which advance from Persia and Baluchistan across Northern India. These disturbances occasionally give very stormy weather in Kashmir, with violent winds on the higher elevations and much snow. The fall is large on the Pir Panjal range, being heaviest in January or February. In the valley and the mountain ranges to the north and east this is the chief precipitation of the year, and is very heavy on the first line of permanent snow, but decreases rapidly eastwards to the Karakoram range. The largest amount is received at Srinagar, Dras, and Anantnag in January. In the Karakoram region and the Tibetan plateau the winter fall is much later than on the outer ranges of the Himalayas, namely from March to May, and the maximum is received in April. The average depth of the snowfall at Srinagar in an ordinary winter is about 8 feet. The snowfall at Sonamarg in 1902 measured 13 feet and in 1903 about 30 feet. In April and May thunderstorms are of occasional occurrence in the valley and surrounding hills, giving light to moderate showers of rain. This hot-season rainfall is of con- siderable importance for cultivation in the valley. From June to November heavy rain falls on the Pir Panjal range, and in Jammu chiefly in the months of July, August, and September. The rainfall at Jammu and Punch is comparable with that of the submontane Districts of the Punjab. It is more moderate in amount in the valley, which receives a total of 9-4 inches, as compared with 35-7 inches at Punch and 26-8 inches at Domel. The precipitation is very light to the east of the first line of the snows bordering the valley on the east, and is about 2 inches in total amount at Gilgit, Skardu, Kargil, and Leh. Thus the south-west monsoon is the predominant feature in Jammu and Kishtwar, while in Ladakh, Gilgit, and the higher ranges the cold- season precipitation is more important. Tables I and II on p. 144 show the average temperature and rainfall at Srinagar and Leh for a series of years ending with 1905.

Earthquakes are not uncommon, and eleven accompanied by loss of life have been recorded since the fifteenth century. In 1885 shocks were felt from the end of May till the middle of August, and about 3,500 people were killed ; fissures opened in the earth, and landslips occurred. Floods are also frequently mentioned in the histories of the country, the greatest following the obstruction of the Jhelum by the fall of a mountain in a.d. 879. The great flood of 1841 in the Indus caused much loss of life and damage to property. In 1893 very serious floods took place in the Jhelum owing to continuous rain for 52 hours, and much damage was done to Srinagar. An inundation of a yet more serious character occurred in 1903.

History

The early history of Kashmir has been preserved in the celebrated Rajatanvigini, by the poet Kalhana, who began to write in 1148. He . gives a connected account of the history of the valley, which may be accepted as a trustworthy record from the middle of the ninth century onwards. Kalhana's work was con- tinued by Jonaraja, who brought the history through the troubled times of the last Hindu dynasties, and the first Muhammadan rulers, to the time of the great Zain-ul-abidin, who ascended the throne in 1420. Another Sanskrit chronicler, Srivara, carries on the narrative to the accession of Fateh Shah in i486 ; and the last of the chronicles, the Rajavalipataka, brings the record down to 1586, when the valley was conquered by Akbar.

The current legend in Kashmir relates that the valley was once covered by the waters of a mighty lake, on which the goddess Parvati sailed in a pleasure-boat from Haramukh mountain in the north to the Konsanag lake in the south. In her honour the lake was known as the Satisar, or ' lake of the virtuous woman.' The country-side was harassed by a demon popularly known as Jaldeo, a corruption of Jalodbhava. Kasyapa, the grandson of Brahma, came to the rescue, but for some time the amphibious demon eluded him, hiding under the water. Vishnu then intervened and struck the mountains at Baramula with his trident. The waters of the lake rushed out, but the demon took refuge in the low ground near where Srinagar now stands, and baffled pursuit. Then Parvati cast a mountain on him, and so de- stroyed the wicked Jaldeo. The mountain is known as Hara Parbat, and from ancient times the goddess has been worshipped on its slopes. When the demons had been routed, men visited the valley in the summer ; and as the climate became milder they remained for the winter. Little kingdoms sprang up and the little kings quarrelled among themselves, with the usual result that a bigger king was called in to rule the country.

The Rajataranginl opens with the name of the glorious king of Kashmir, Gonanda, ' worshipped by the region which Kailasa lights up, and which the tossing Ganga clothes with a soft garment.' Nothing is known of the founder of the dynasty, though the genealogists of Jammu trace a direct descent from Gonanda to the present ruler. Mention is made of the pious Asoka and of his town, Srinagar, with its ninety-six lakhs of houses resplendent with wealth. This town probably stood in the neighbourhood of the Takht-i-Sulaiman. Next come the three kings, Hushka, Jushka, and Kanishka, to be identified with Huvishka, Vasudeva, and Kanishka, the Kushan rulers of Northern India at the beginning of the Christian era. According to the chronicles, in the days of these kings Kashmir was in the possession of the Buddhists, and Buddhist tradition asserts that the third great council held by Kanishka took place in Kashmir. The Buddhist creed and the Brah- manical cult seem to have existed peaceably side by side ; but five hundred years later Hiuen Tsiang found the mass of the people Hindu, and the monasteries few and partly deserted. There is good reason to believe that the Kashmiris were, from the earliest period, chiefly Saivas.

About a.d. 528, Mihirakula, the king 'cruel as death,' ruled over Kashmir. He was the leader of the White Huns or Ephthalites. The people still point to a ridge on the Plr Panjal range, Hastlvanj, where the king, to amuse himself, drove one hundred elephants over the precipice, enjoying their cries of agony. King Gopaditya was a pleasing contrast to the cruel king, and did much to raise the Brah- mans, and to advance their interests. Pravarasena II reigned in the sixth century and, returning from his victorious campaigns abroad, built a magnificent city on the site of the present capital of Kashmir. The city was known as Pravarapura, and is mentioned by Hiuen Tsiang at the time of his visit (a.d. 631) as the ' new city.' The site chosen has many advantages, strategic and com- mercial, but it is liable to floods. Many subsequent rulers endeavoured to move the site of the capital, but their efforts failed. Among these was the celebrated Lalitaditya, who ruled in the middle of the eighth century, and received an investiture from the emperor of China. A great and victorious soldier, he subdued the kings of India and invaded Central Asia. After twelve years of successful campaigning he returned to Kashmir, enriched with spoil and accompanied by artisans from various countries, and built a magnificent city, Paraspur (Parihasapura). To give this new town pre-eminence, he burnt down Pravarapura. Lalitaditya also built the splendid temple of Martand. Before leaving for further conquests in Central Asia, from which he never returned, the king gave his subjects some excellent advice. He warns them against internal feuds, and says that if the forts are kept in repair and provisioned they need fear no foe. In a country shut in by mountains, discipline must be strict, and the cultivators must not be left with grain more than sufficient for a year's requirements. Cultivators should not be allowed to have more ploughs or cattle than are absolutely neces- sary, or they will trespass on their neighbours' fields. They should be repressed, and their style of living must be lower than that of the city people, or the latter will suffer. These words spoken some 1,200 years ago have never been forgotten ; and rulers of various races and religions have followed Lalitaditya's policy, and sternly subordinated the interests of the cultivators to the comfort of the city.

Sankara Varman (883-902) was another great conqueror; and it is stated that, though Kashmir had fallen off in population, he was able to lead out an army of 900,000 foot, 300 elephants, and 100,000 horse. Sankara Varman was avaricious and profligate. He plundered Paraspur in order to raise the fame of his own town, now known as Pattan. There were signs of decay, and the last of the strong Hindu rulers was queen Didda (950-1003). Then followed the Lohara dynasty. Central authority was weakened, the country was a prey to civil war and violence, and the Damaras, skilled in burning, plundering, and fighting, harassed the valley. The last of this line was Jaya Simha, or Simha Deva (1128); and in his reign the Tartar, Khan Dalcha, invaded Kashmir, and after great slaughter set fire to Srlnagar. He subsequently perished in the passes on his retreat from Kashmir, over- taken by snow. Ram Chand, the commander-in-chief of the Kashmir army, had meanwhile kept up some semblance of authority in the valley, and had routed the Gaddis from Kishtwar. With Ram Chand were two soldiers of fortune, Rainchan Shah from Tibet and Shah Mirza from Swat.

Rainchan Shah quarrelled with Ram Chand, and with the assistance of the Ladakhis attacked and killed him. He married Kuta Rani, the daughter of Ram Chand, and embracing Islam became the first Muhammadan king of Kashmir, but died after a short reign of two and a half years. At this juncture Udayanadeva appeared, who was the brother of Raja Simha Deva and had fled to Kishtwar. He married the widow, Kuta Rani, and reigned for fifteen years. On his death Kuta Rani assumed power for a short time, and committed suicide rather than marry Shah Mirza, who now declared himself king. He was the first of the line known as Salatln-i- Kashmir, and took the name of Shams-ud-dln. In 1394 Sultan Sikandar, known for his fierce zeal as Butshikan or ' iconoclast,' was king of Kashmir. He was a gloomy fanatic, and destroyed nearly all the grand buildings and temples of his Hindu predecessors. To the people he offered death, conversion, or exile. Many fled ; many were converted to Islam ; many were killed, and it is said that Sikandar burnt seven maunds of sacred threads worn by the murdered Brahmans. By the end of his reign all Hindu inhabitants of the valley, except the Brahmans, had probably adopted Islam.

In 1420 Zain-ul-abidln succeeded. He was wise, virtuous, and frugal, and very tolerant to the Brahmans. He remitted the poll-tax on Hindus, encouraged the Brahmans to learn Persian, repaired some of the Hindu temples, and revived Hindu learning. Hitherto in Kashmir Sanskrit had been written in Sarada, an older sister of the Devanagarl character. The introduction of Persian, as the official language, divided the Brahmans into three subdivisions : the Karkuns, who entered official life ; the Bachabatts, who discharged the function of the priesthood ; and the Pandits, who devoted themselves to Sanskrit learning. Towards the end of this good and useful reign the Chakks sprang into mischievous prominence. Zain-ul-abidln drove them out of the valley, but in the time of his weak successors they returned and eventually seized the government of Kashmir. Turbulent and brave, the Chakks were not fitted for administration. Yakub Khan, the last of the line, offered a stubborn resistance to Akbar, and with the help of the Bambas and Khakhas routed the Mughal on his first attempt on the valley (1582). But later, not without difficulty and some reverses, Kashmir was finally conquered (1586) 1 .

Akbar visited the valley three times. He built a strong fort on the slopes of the Hara Parbat, paying high wages, and dispensing with forced labour. His revenue minister, Todar Mai, made a very summary record of the fiscal conditions of the valley. Jahanglr was greatly attached to Kashmir. He laid out lovely pleasure-gardens ; around the Dal Lake were 777 gardens, yielding a revenue of 1 lakh from roses and bed musk. Much depended on the character of the governors. All Mardan Khan, the best of these, built a splendid series of sarais on the Plr Panjal route to India, and grappled with a famine with energy and success. Aurangzeb visited the valley only once ; but in that brief time he showed his zeal against the unbelievers, and his name is still execrated by the Brahmans. Then followed the disorder of decay, and in 1751 the Subak of Kashmir was practically independent of Delhi.

From the following year the unfortunate Kashmiris experienced the cruel oppression of Afghan rule, the short but evil period of the Durranis. Governors from Kabul plundered and tortured the people indiscriminately, but reserved their worst cruelties for the Brahmans, the Shiahs, and the Bambas of the Jhelum valley. In their agony the people of Kashmir turned with hope to the rising power of Ranjlt Singh of Lahore. In 18 14 a Sikh army advanced by the Plr Panjal, Ranjlt Singh watching the operations from Punch. This expedition miscarried ; but in 18 19 Misr Dlwan Chand, Ranjlt Singh's great general, accompanied by Gulab Singh of Jammu, overcame Muhammad Azlm Khan, and entered Shupiyan. In comparison with the Afghans, the Sikhs came as a relief to the unfortunate Kashmiris, but their rule was harsh and oppressive.

Sher Singh, the reputed son of Ranjlt Singh, was a weak governor, and his name is remembered in connexion with the terrible famine which visited the valley. The best of the Sikh governors was Colonel Mian Singh (1833), wno 1S s ^ spoken of with gratitude, and did his best to repair the ravages of the famine. He was murdered by

1 Kashmir had been attacked from the side of Ladakh by Mirza Haidar (the author of the Tarikh-URashidi) in 1532, and again invaded from the south in 1540, and ruled by him (nominally on behalf of the emperor Humayiin) until his death eleven years later. mutinous soldiers, and was succeeded by Shaikh Ghulam Muhl-ud-din in 1842. During his government the Bambas, under Sher Ahmad, inflicted great losses on the Sikhs. In 1845 Imam-ud-din succeeded his father as governor.

The history of the State, as at present constituted, is practically the history of one man, a Dogra Rajput, Gulab Singh of Jammu. Lying off the high roads of India, and away from the fertile plains of the Punjab, the barren hills of the Dogras had not attracted the notice of the Mughal invaders of India. Here lived a number of petty Rajas, and it appears that from very early times the little kingdom of Jammu was locally of some importance, Towards the end of the eighteenth century the power of the Jammu ruler had extended east as far as the Ravi, and west to the Chenab ; but the power waned and waxed according to the fortunes of petty and chronic warfare. To the east, at Basoli and Kishtwar, were independent Rajput chiefs, while to the north-west were the Muhammadan rulers of Bhimbar and Rajaori, descendants of Hindu Rajputs. These two states lay on the Mughal route to Kashmir, and so came under the influence of Delhi. Up the Jhelum valley, the country was held by small independent Muham- madan chiefs, whose title of Raja suggests their Hindu origin.

About the middle of the eighteenth century Raja Ranjlt Deo was the ruler of Jammu. He was a man of some mark, and his capital flourished ; but at his death about 1780, his three sons quarrelled. The Sikhs were invoked, and Jammu was plundered. From Ranjlt Deo's death to 1846, the Dogra country became tributary to the Sikh power. Gulab Singh, Dhyan Singh, and Suchet Singh were the great- grandsons of Surat Singh, youngest brother of Ranjlt Deo. They were soldiers of fortune, and as young men sought service at the court of Ranjlt Singh of Lahore. They rapidly distinguished themselves ; and Gulab Singh, for his service in capturing the Raja of Rajaori, who was fighting the Sikhs, was created Raja of Jammu in 1820. Dhyan Singh obtained the principality of Punch, a hilly country between the Jhelum and the Plr Panjal range, north of Rajaori ; while Suchet Singh received Ramnagar, west-by-north of Jammu.

Ranjlt Singh had found that the control of the Dogra country was a difficult task, and his policy of enlisting the services of able Dogras was at once obvious and prudent. The country was disturbed, each man plundered his neighbour, and Gulab Singh's energies were taxed to the utmost in restoring order. He was a man of extraordinary power, and very quickly asserted his authority. His methods were often cruel and unscrupulous, but allowances must be made. He believed in object-lessons, and his penal system was at any rate successful in ridding the country of crime. He kept a sharp eye on his officials, and a close hand on his revenues. Rapidly absorbing the power and possessions of the feudal chiefs around him, after ten years of laborious and consistent effort he and his two brothers became masters of nearly all the country between Kashmir and the Punjab, save Rajaori. Bhadarwah fell easily into the hands of Gulab Singh after a slight resistance. In Kishtwar, the minister, Wazir Lakhpat, quarrelled with the Raja and sought the assistance of Gulab Singh, who at once moved up with a force, and the Raja surrendered his country without fighting.

His easy successes in Kishtwar, which commanded two of the roads into Ladakh, probably suggested the ambitious idea of the conquest of that unknown land. The difficulties of access offered by mountains and glaciers were enormous ; but the brave Dogras under Gulab Singh's officer, Zorawar Singh, never hesitated, and in two campaigns the whole of Ladakh passed into the hands of the Jammu State. It is interesting to notice that the Dogras did not pillage the rich monastery of Himis, which saved itself by allowing the army in ignorance of its locality to pass the gorge leading to the Himis valley, and then sending a deputation with an offer of free rations while in Ladakh territory. The agreement made was respected by both parties.

A few years later, in 1840, Zorawar Singh invaded Baltistan, captured the Raja of Skardu, who had sided with the Ladakhis, and annexed his country. The following year (1841) Zorawar Singh while invading Tibet was overtaken by winter, and, being attacked when his troops were disabled by cold, perished with nearly all his army. Whether it was policy or whether it was accident, by 1840 Gulab Singh had encircled Kashmir.

In the winter of 1845 war broke out between the British and the Sikhs. Gulab Singh contrived to hold himself aloof till the battle of Sobraon (1846), when he appeared as a useful mediator and the trusted adviser of Sir Henry Lawrence. Two treaties were concluded. By the first the State of Lahore handed over to the British, as equiva- lent for one crore of indemnity, the hill countries between the rivers Beas and the Indus ; by the second the British made over to Gulab Singh for 75 lakhs all the hilly or mountainous country situated to the east of the Indus and west of the Ravi. Kashmir did not, however, come into the Maharaja's hands without fighting. Imam-ud-dm, the Sikh governor, aided by the restless Bambas from the Jhelum valley, routed Gulab Singh's troops on the outskirts of Srlnagar, killing Wazir Lakhpat. Owing, however, to the mediation of Sir Henry Lawrence, Imam-ud-din desisted from opposition and Kashmir passed without further disturbances to the new ruler. At Astor and Gilgit the Dogra troops relieved the Sikhs, Nathu Shah, the Sikh commander, taking service under Gulab Singh. Not long afterwards the Hunza Raja attacked Gilgit territory. Nathu Shah retorted by leading a force to attack the Hunza valley ; he and his force were destroyed, and Gilgit fort fell into the hands of the Hunza Raja, along with Punial, Yasin, and Darel. The Maharaja sent two columns, one from Astor and one from Baltistan, and after some fighting Gilgit fort was recovered. In 1852, partly by strategy, partly by treachery, the Dogra troops were annihilated by the bloodthirsty Gaur Rahman of Yasin, and for eight years the Indus formed the boundary of the Maharaja's territories.

Gulab Singh died in 1857: and when his successor, Ranblr Singh, had recovered from the strain caused by the Mutiny, in which he had loyally sided with the British, he determined to recover Gilgit, and to rehabilitate the reputation of the Dogras on the frontier. In i860 a force under Devi Singh crossed the Indus, and advanced on Gaur Rahman's strong fort at Gilgit. Gaur Rahman had died just before the arrival of the Dogras. The fort was taken ; and since then the Maharajas of Jammu and Kashmir have held it, to their heavy cost and somewhat doubtful advantage.

Ranblr Singh was a model Hindu : devoted to his religion and to Sanskrit learning, but tolerant of other creeds. He was in many ways an enlightened man, but he lacked his father's strong will and deter- mination, and his control over the State officials was weak. The latter part of his life was darkened by the dreadful famine in Kashmir, 1877-9; an d in September, 1885, he was succeeded by his eldest son, the present Maharaja Pratap Singh, G. C.S.I. He bears the hereditary title of Maharaja, and receives a salute of 19 guns, increased to 21 in his own territory.

Through all these vicissitudes of government and changes in religion the Kashmiri has remained unaltered. Mughal, Afghan, Sikh, and Dogra have left no impression on the national character ; and at heart the people of the valley are Hindus, as they were before the time of Sikandar Shah. The isolation from the outer world accounts for this stable unchanging nationality, and passages in the Rajatarangi?il show that the main features of the national character were the same in the early period of Hindu rule as they are now.

The valley of Kashmir is holy land, and everywhere one finds remains of ancient temples and buildings called by the present inhabi- tants, though without historical foundation, Pandavlari, ' the houses of the Pandavas.' These ancient buildings, though more or less injured by iconoclasts, vandal builders, earthquakes, and, as Cunningham thinks, by gunpowder, are composed of a blue limestone capable of taking the highest polish, and of great solidity. They defy weather and time, while the later works of the Mughals, the mosques of Aurangzeb and the pleasure-places of Sallm and Nur Mahal, are crumbling away and possess little or none of their pristine beauty.

The Hindu buildings of Kashmir have been described by Sir Alexander Cunningham and Mr. F. S. Growse 1 . They exhibit traces of the influence of Grecian art, and are distinguished by the graceful elegance of their outlines, by the massive boldness of their parts, and by the happy propriety of their decorations. Characteristic features are the lofty pyramidal roofs, trefoiled doorways covered by pyramidal pediments, and the great width of the space between columns. Among the numerous temples two may be noticed — Martand and Payech — the first for its grandeur, and the second for its excellent preservation. Martand, the Temple of the Sun, stands on a sloping karewa, about 3 miles east of Islamabad, overlooking the finest view in Kashmir. The great structure was built by Lalitaditya in the eighth century. Kalasa came here at the approach of death and expired at the feet of the sacred image (1089). In the time of Kalhana the chronicler, the great quadrangular courtyard was used as a fortification, and the sacred image is said to have been destroyed by Sikandar, the iconoclast.

The building consists of one lofty central edifice, with a small detached wing on each side of the entrance, the whole standing in a large quadrangle surrounded by a colonnade of eighty-four pillars with intervening trefoil-headed recesses. The length of the outer side of the wall, which is blank, is about 90 yards ; that of the front is about 56 yards. The central building is 63 feet in length by 36 feet in width, and, alone of all the temples of Kashmir, possesses, in addition to the cella or sanctuary, a choir and nave, termed in Sanskrit the autarala and arddhaniaiulapa ; the nave is 18 feet square. The sanctuary alone is left entirely bare, the two other compartments being lined with rich panellings and sculptured niches. As the main build- ing is at present entirely uncovered, the original form of the roof can be determined only by a reference to other temples and to the general form and character of the various parts of the Martand temple itself. It has been conjectured that the roof was pyramidal, and that the entrance chamber and wings were similarly covered. There would thus have been four distinct pyramids, of which that over the inner chamber must have been the loftiest, the height of its pinnacle above the ground being about 75 feet.

The interior must have been as imposing as the exterior. On ascending the flight of steps, now covered by ruins, the votary entered a highly decorated chamber, with a doorway on each side covered by a pediment, with a trefoil-headed niche containing a bust of the Hindu triad, and on the flanks of the main entrance, as well as on those of the side doorways, were pointed and trefoil niches, each of which held a statue of a Hindu deity. The interior decorations of the roof can only be determined conjecturally, as there do not appear to be any 1 Calcutta Review, No. CVII. ornamented stones that could with certainty be assigned to it. Baron Hiigel doubts whether Martand ever had a roof ; but as the walls of the temple are still standing, the numerous heaps of large stones that are scattered about on all sides suggest the idea that these belonged to the roof. Fergusson, however, thought that the roof was of wood. Payech lies about 19 miles from Srlnagar under the Naunagri karewa, about 6 miles from the left bank of the Jhelum river. On the south side of the village, situated in a small green space near the bank of the stream surrounded by a few walnut and willow trees, stands an ancient temple, which in intrinsic beauty and elegance of outline is superior to all the existing remains in Kashmir of similar dimensions. Its excellent preservation may probably be explained by its retired situation at the foot of the high table-land, which separates it by an interval of 5 or 6 miles from the bank of the Jhelum, and by the mar- vellous solidity of its construction.

The cella, which is 8 feet square,

and has an open doorway on each of the four sides, is composed of only

ten stones, the four corners being each a single stone, the sculptured

tympanums over the doorways four others, while two more compose

the pyramid roof, the lower of these being an enormous mass, 8 feet