Kalidas

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Kalidas

By Intizar Hussain

The play Malavikagnimitram commonly known as Malavika.

Malavika is, as claimed by the researchers, his earliest play. The other two plays, written in later years, are Vikram Urvashi and Abhijanana Shakuntala commonly known as Shakuntala. In fact, the researchers after much research have been able to dig out only three plays and four poems. Of the four poems more popular are Ritu Singhar and Maighdoot.

We don’t know much about Kalidas. Of course in the history of Sanskrit literature he stands as a great poet and a great playwright. But the researchers have neither been able to trace all his writings nor been able to trace his biographical details. Legends about him are many, but facts and events of his life are missing. He is said to have lived in the times of the great king Raja Vikramaditya and that he was associated with his court. But Vikramaditya himself is more a legend than a historical figure. Tales and legends associated with him are plentiful.

He is also supposed to be the founder of Summat era. So the current Indian calendar owes its existence to him. And yet researchers are not very sure if a king with this name ever existed. Of a number of theories, one is that the Gupta king Chandragupta II had assumed the title of Vikramaditya.

But what tickled me more were the researches made by an Ujjaini Urdu writer. An elderly man with white beard clad in sherwani and pajama could easily be marked too as one different from the writers and intellectuals around us. He was kind enough to give me his work on Kalidas titled as Kali Das, Aai Mutalia. His name was Mahmood Zaki.

I wanted to know if he is a genuine Ujjaini or an outsider who under the pressure of circumstances found himself compelled to settle here. He asserted that Ujjain is his ancestral home. Born and brought up in this land he developed a love for Kalidas. And he says that a Sanskrit scholar Pandit Suriya Narain Vyas, seeing his involvement in Kalidas, exhorted him to translate his works in Urdu. Encouraged by him, he first translated Vikram Urvashi in Urdu. Later on he planned to write a book on Kalidas with particular reference to the translations of his plays and poems in Urdu.

In this book Mahmood Zaki’s research tells us that the history of Sanskrit literature bears the evidence of eight writers writing under the name of Kalidas. The plays and poems written by them are 51 in number. The scholars after much research and scrutiny marked out three plays and four poems as the works of the genuine Kalidas known to us a Maha Kavi Kalidas. What he wrote first was the poem Ritu Singhar.

Mahmood Zaki tells us that of all the works of Kalidas Shakuntala has been very popular with the Europeans. It has been translated and re-translated at different times in the different languages of Europe. The earliest was the English translation done in 1789 by Sir William Jones.

Mahmood Zaki has established through his research that long before this translation in English, the play had been translated in Urdu. Nawaz Kabsher, a Muslim, had translated it in Urdu in 1680. He quotes Prof Shirani saying that Nawaz had translated it at the behest of Auranzaib’s son, Alam Shah.

Zaki Sahib enumerated a number of translations during the nineteenth century to be followed by those done in the twentieth century. Their total number, according to him, is more than 30. He has also provided information about different translations of Vikram Urvashi including the one by him. But he avoids discussing the quality of these translations.

I feel that those who have relied on their heavily Persianised expression have miserably failed in conveying the flavour of the original in Urdu. Aziz Lucknavi’s translation of Vikram Urvashi is an example of this kind of translation.

Akhtar Husain Raipuri’s translation of Shakuntala is perhaps more authentic as because of his acquaintance with Sanskrit he had an access to the original text. Secondly, he seems to have an understanding that Sanskrit classics, when being translated in Urdu, cannot reconcile with Persianized expression.

However, Mahmood Zaki’s survey tells us that Kalidas is in no way a stranger to Urdu. We have the whole of Kalidas translated and retranslated in our language.

Nayikas

HARSHA V DEHEJIA, Kalidasa’s Nayikas, July 4, 2020: The Times of India

From: HARSHA V DEHEJIA, Kalidasa’s Nayikas, July 4, 2020: The Times of India

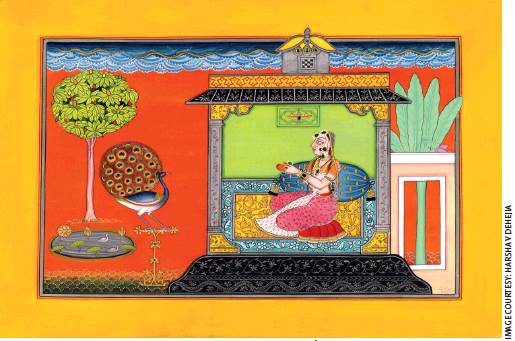

Through his nayikas, the poet reveals the social norm of his times wherein human emotion was celebrated, writes HARSHA V DEHEJIA

To enter the mind of Kalidasa is to enter the world of beauty, of regal spaces and mythic narratives, of sensuous nayikas and sonorous sounds, of evocative words and ornamented phrases, of unhurried elegance and silken shringara, of serene hermitages and opulent havelis, of changing seasons with its unique flora and fauna, of pathways in the sky that look down upon the earth in their journey, and above all, of the beauty of human emotions.

In the absence of credible socio-historic data of the life and times of Kalidasa, our point of entry into his mind is by way of his works and through that, perhaps, come to some historical presumptions of the life and times in which the poet lived. More importantly, we will be privy to his artistry and aesthetic mastery. And what an inspired and radiant mind it was. His words are our only guide: words in chaste Sanskrit and everyday Prakrit that are both shreya and drashya — heard and visible — melodic to the ear and an invitation to create mental images or mindscapes.

One of many pathways into his mind is through his depiction and celebration of prakriti, the feminine, understood both as the nayikas that inhabit his plays as well as the world of nature in which the nayikas unfold their feelings. His was a world of colour and aroma, of the universe of nature that resonates with the mind, but above all, his was not a world-denying world.The feminine in Kalidasa is not just the nayika that inhabits his plays and poetry, but even more the world of nature in which the human condition is played out. Both are interwoven, one resonating with the other, each has delicate feelings and is bhava pradhan, predominantly feeling oriented, every leaf responding to every shade of emotion, and every colour of human emotion reflected in the hues of the world around it.

For Kalidasa, the woman and nature are interconnected in an animated tapestry, a fabric where if the nayika is the warp, nature is the weft.

Kalidasa was a court poet and it may be entirely possible that his creations were for poetic and aesthetic enjoyment rather than a moralistic, theatrical performance, for one does not find too many stage directions in his plays. His creations were rasa kavyas, poetry, rather than dharma kavyas or dharma natya. His nayikas were not historical women but even though they were drawn from epics and Puranic sources they were closer to the ideal feminine of ancient India, which the Kamasutra speaks about and that speaks to us even today.These nayikas are one of many windows into the mind of Kalidasa.Whether it is the virahini yakshi, the romantic Shakuntala, the demure Parvati, the woman who resonates with every ritu, season, the mythic Urvashi and regal Malavika, all of Kalidasa’s nayikas are elegant and graceful and shine with grace and nobility, the glow of shringara or the majesty of a queen. In making his nayikas both kamaniya, desirable, and ramaniya, delightful, Kalidasa was expressing the social norm of his times where women were unabashedly sensual, where the celebration of shringara was an act of noble and gracious living, where human emotion was upheld and celebrated and where women stood shoulder to shoulder with men in every walk of life.

The time of Kalidasa was one where sahitya flowed like wine, where poets were on equal footing with pandits, where the beauty of words rivalled the looks of sensuous women and where alankara, ornamentation, was reserved not just for human beings but was a part of the spoken word. Kalidasa expresses this celebration of feminine sensuality in most of his creations, particularly in the Meghadutam, Shakuntalam and Ritusamhara.