Karachi: A-E

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Karachi1

Karachi: Baghe Ibne Qasim

In The Park By The Sea

By Maryam Murtaza Sadriwala

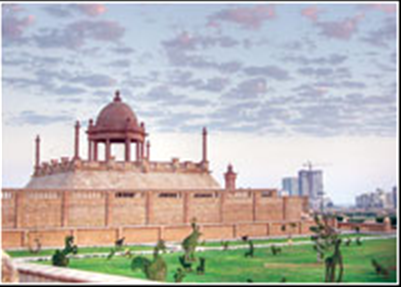

It’s every Karachiitte’s Sunday dream come true! Spread spaciously across a sprawling 130 acres, over looking the crashing waves of the Arabian Sea, sits the magnificent park christened, Baghe Ibne Qasim.

Structured on two levels and boasting of immaculately manicured green lawns, concrete umbrellas for picnickers, cosy wooden benches: it’s ideal for a family evening picnic. That’s the reason why you will find this enormous park packed to the hilt on the weekends.

Established by City District Government in Karachi, its novelty also lies in the fact that it is adjacent to the unique Jahangir Kothari Parade. The symbolic Jahangir Kothari parade, along the Clifton coastline, consists of a main promenade that serves as a gathering platform, through which a number of wide steps descend to a walkway, which stretches some half a kilometre towards a covered pavilion. This pavilion at the time of its construction was built right above the crashing waves of the Clifton beach. These interconnected structures allow a visitor to view the sea from different heights and angles.

The most striking part of the whole monument is the bandstand or cupola of pink Jodhpur stone. Built at the western part of the grand monument, it is defined by four tall pillars at each end, topped by carved motifs, while carved balustrade and podium walls add a unique charm to the structure.

Work to build this monument began in 1919 and was completed a year later. It was financed by a Parsi philanthropist and astute businessman, Jehangir Kothari, on a personal wish of Lady Lloyd, wife of the then Governor of Bombay, Lord George Lloyd. Lady Lloyd wished to walk up to the sea, without getting her feet wet.

Under the keen eye of the esteemed British architect, E. B. Hoare, the parade was constructed by an amalgamation of Jodhpur sandstone and Gizri limestone. On one side of the monument is the Lady Lloyd Pier; while on the other side is Jehangir Kothari’s bungalow. At the time when the Parade was built, this bungalow was the sole edifice on the then-desolate Clifton beach.

Positioned majestically at the junction of Sharah-i-Firdousi and Shahrah-i-Iran, directly in front of the happening Park Towers shopping mall, this Parade and now the Bin Qasim Park are quite the place to be in Clifton today. So pack up a delectable tea-time snack and whisk your family off to lounge in this park this Sunday evening and be sure to relish the balmy sea air and great architecture.

Karachi: Bahadurabad

Roadside kebabs

By Osman Samiuddin

Karachi’s Bahadurabad isn’t what it used to be and Zameer Ansari doesn’t want me to write about his kebabs: what has the world come to? Ansari’s shyness is jarring in this new Bahadurabad, for there is little here that doesn’t want to be written about. In fact, shouted about.

Bahadurabad can’t help but prompt one dilemma of Karachi, of any metropolis actually: what cost development? On the main road in, where once Universal Bookstore beckoned discreetly, maybe after a burger at King Burger and a haircut at Standard (“Would you like disco-rock look?”), now stands a mall. Docker’s yells out its wares, its neighbour promises a sports active lifestyle.

Round the corner, the sickly, pale green walls of Amber cinema have breathed their last, to be replaced by flats. Karachi needs another block of flats like the world needs four more years of Bush, but with more people coming in to make more life, so where else to put them? Life, not film, must win.

Sad to say, even the mohallah smuggler –– every mohallah had one –– has been trampled by progress. Competition is now too fierce; a game played out by too many and like the corner shop in the face of the branded superstore, they have perished. Development has, funnily, left the roads and power networks untouched.

Up on Alamgir Road, Zameer Ansari, who doesn’t want his kebabs written about for fear of being cursed, is also new. He has reason to fret, for the Zameer Ansari Kebab Centre wears its success easily. At its heart, it is a traditional roadside kebab house but it is a brasher take, its head tilted to modernity.

It is not, please note, a house but that contemporary concoction, the centre, churning out highly qualified kebabs for the country’s uplift. “A centre”, the neon sign educates, “of barbeque excellence”. They have business cards and cater to parties. Opposite Alamgir Masjid it stands, adjacent to Alamgir Healthcare (ominously close?) and nearby is a wedding hall. Thus it makes a fitting, rectangular slice of Karachi life: food, religion, marriage and death. A cricket ground nearby would’ve made a full circle of the rectangle.

The centre is five years young. Its food is years old. Delhi’s influence has not passed by Alamgir Road’s people or its food. The popular favourite is the Malai Chicken Tikka Boti, a verdict that brooks little argument here. The chicken Reshmi Kebab, which disintegrates into a million tiny, tasty amulets upon entering the mouth, is not far behind.

Make sure too that the Hari Bihari Chicken is not far from hand or mouth. The name misleads for unless the chef was Bihari (a key ingredient I am told to most Bihari cuisine), little about it is from there. The owner reveals it to be from Muradabad. Forget the ethnicity, enjoy the flavour instead, a truism that works equally for the city and its citizens.

Another nod to fashion, unwitting as it is, is the superiority of the chicken to beef. Red meat, we are told, is not so healthy, so go white. It is also the path to follow here: the Dhaaga Beef kebab and kebab fried are in no way poor, but neither are they, in any way, outstanding. A little too easy with the spices too, they reaffirm the belief that unless you are English, you can’t really go wrong with kebabs, but you have to be special to make it special. Fashionable too is the service; Pakistanis are fashionably late, but waiting over half an hour for barbeque food does no one proud.

If choice permits, skip indoors. Not because the chairs are uncomfortable, the tables wonky and the interior too tube-lit; not even because of the lonely insects. No, take the roadside experience if only to save your eyes from the relentless ferocity of the smoke billowing through from the grills downstairs, unless you don’t mind telling friends that the scent you’re brazenly wafting is, in fact, eau de kebab (“barbeque collection, darling”).

Surrounding development hasn’t so much touched prices, five adults scoffing away for under Rs500. Bahadurabad isn’t what it used to be and Zameer Ansari didn’t want me to write about his kebabs, but on farewell he says he will provide Malai Chicken when I get married. In which case, I might have to get married repeatedly.

Karachi: Bunder Road

A Visit To The Past

The hustle and bustle and old world charm of Eidgah exemplify the spirit of Karachi, re-discovers R. Husain

The old central business district of Karachi, M.A. Jinnah Road, is still popularly known by its old name ––- ‘Bunder Road’ ––- though it was changed nearly fifty years ago. This area has an ambience all its own, with distinct characteristics representing the exuberance and energetic spirit of Karachi. In a dyspeptic frame, one is likely to feel repulsed by the noisy hustle and bustle and the pollution, but for those who are in a better mood and attracted to the old-world charm hidden inside the vibrant, crowded bazaars and forgotten mansions; it is a treat to be walking around here.

I was at the Eidgah Maidan area of M.A. Jinnah Road to order a replacement of chiks (reed blinds) for my house. This area, only a few years ago, had scores of shops that sold ready-made and made-to-order blinds, but now only some of them make use of the natural sirkanda which is imported from Kasur, Punjab. Most of the original shops have begun dealing in plastic merchandise. There are now shops selling plastic durries, mats and table covers. The chik-makers, too, use plastic pulleys instead of the handmade wooden pulleys that were traditionally a part of every chik.

Walking up and down the area, I came across small mosques and dargahs in the narrow lanes. Directly opposite the shops selling flowers and chaadars as an offering for the saints, amid the rose fragrance, are shops selling an eclectic range of forged and cast iron-ware. However, I was pleased to note that the atar shops are still there along the main road. The atar-walas continue to manufacture incense and distil atar for festivals such as Eid as this indigenous perfume is vastly popular even today, with different communities using unique concoctions. Some of the Eidgah atar shops also sell creams, lotions, masks, ubtan and henna…all the ingredients for a fair and lovely bride-to-be.

Viewing the road-crossing at Eidgah from the relative safety of the footpath, I observe the traffic madness ––- the speeding buses, the zig-zagging motorbikes and scooters, the bravado of pedestrians, the boldness of hand-drawn cart-walas such as the bihishtees, the impudence of taxi-drivers and private car owners, as well as the racket caused by the rickshaws. Nevertheless, oblivious of what goes on around them, women –– most of them burqa-clad housewives -–– flock to the shops selling footwear, vinyl floor coverings, plastic mats, iron utensils and rolling pins. They are also out to buy fabrics and other bric-a-brac at the Jama Cloth Market close by, or to fulfill a mannat at one of the dargahs. Whatever it is, if you do not already belong to the old city, a visit to Eidgah will certainly transport you into another era.

Karachi: cannon

Karachi’s cannon

During the mid 50s, when Karachi was the capital of Pakistan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (Sept 12, 1956 – Oct 17, 1957), the then prime minister, issued a directive for the removal of an illegal encroachment comprising a mosque and huts in the Saddar area. The illegal structure was razed and the land was vacated without much of a fuss.

The land was then earmarked for a co-operative market. During the digging work for the construction of the market’s basement, one large-size cannon was unearthed. I and my schoolmates were among other spectators who rushed to the site. Actually, we bunked our classes to see what had come out of the earth.

The KMC staff involved in the digging brought this heavy piece of metal from the construction site and perhaps dumped it at old Burnes Gardens along with other antiques. (The practice continued in later years as Queen Victoria’s statue was removed from Frere Hall in the mid sixties). The cannon then resurfaced in front of the water board building near KDA Chowrangi in North Nazimabad.

The cannon could have been taken away long ago by heroin addicts who wander the area in packs to steal small pieces of metal to satisfy their drug fix in the evening. But this iron antique – perhaps 200 years old – was too heavy to be carried away on shoulders.

Actually, the Saddar area from where it was excavated was known as Gun Range till the First World War and in our lingua franca as ‘Artillery Maidan’. The cannon, left out purposely or otherwise by the British, was brought here by General Napier from Punjab during his Sindh campaign.

Its sister cannon of that era, now known as ‘Bhangi’s top’ locally, was fully restored long ago and suitably placed at Lahore’s Mall in splendid view of commuters and tourists.

While passing through KDA Chowrangi last week I saw the cannon, excavated from Saddar, half buried in a mass of concrete. The antique awaits the attention of the authorities as it badly needs a facelift like that of the Chaghi mountain replica in Islamabad or different hulks of aircrafts on display at roundabouts in Nazimabad and North Nazimabad.

It’s hoped that its honour would be fully restored and the cannon would be suitably placed before any successful attempt by heroin addicts.—Kunwar Khalid Yunus

Charminar in Karachi

By M. Rafique Zakaria

While in Karachi, if you happen to cross Bahadurabad Chowrangi you will look at a structure right in the middle of the four roads converging on the chowrangi. A close look at the structure will reveal that it is a replica of the famous Charminar located in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India.

The original Charminar was built by Quli Qutb Shah when he shifted his capital from Golkonda Fort to Hyderabad in 1591. The structure of the Charminar consists of four minarets and each has a length of 20 metres. It is an excellent example of the Indo-Islamic style of architecture.

This scribe photographed the original Charminar on January 7, 2007 and its replica, which is still under construction, on February 20, 2007.

The Charminar at Bahadurabad Chowrangi will be used as a mosque.