Karachi: F-K

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Karachi: Frere Hall

Frere Hall: Standing Tall

By Maryam Murtaza Sadriwala

There are a few landmarks, which epitomise Karachi and reflect this phenomenal city’s grandeur. Frere Hall is one of them. Standing as a lofty reminder of the British Raj and leaving its mark of Venetian Gothic architecture, the building has withstood the ravages of time for the last 140 years.

The Hall whose construction was completed in 1865, today stands majestically between Abdullah Haroon Road (formerly Victoria Road) and Fatima Jinnah Road (formerly Bonus Road) in the vicinity of a famous five Star Hotel, the closed building of the US Consulate and Consul General’s house, the Japanese Consulate and the Sind Club.

It was built in the honour of Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere (1815-1884), who was known for promoting economic development in Karachi.

This edifice of yellowish limestone, red and grey Jungshahi sandstones was designed by Colonel Clair Wilkins whose proposal was selected from 12 entries, in which the first was perhaps recorded architectural design competition for a public building in Sindh. The structure cost Rs1,80,000 out of which Rs22,500 was raised for the memorial through public donations and was officially inaugurated by Commissioner Mansfield on October 10, 1865.

Frere Hall served as a Town Hall and was the hub of Karachi’s socio cultural activities at the time of the British Raj. During the same period it housed a number of busts including King Edward VII’s which was a gift from Seth Edulji Dinshaw. It also housed oil paintings of former Commissioners in Sindh including Sir Charles Pritchard and Sir Evan James.

The ground floor houses, a fine public library named Liaquat National Library (after Liaquat Ali Khan, first Pakistani Prime Minister of Pakistan). It is one of the largest libraries of Karachi, which contains over 70,000 books, including rare and handwritten manuscripts, newspapers, dictionaries, atlases and technical books. The upper floor serves as an art gallery containing masterpieces of Pakistan’s famous calligrapher and painter Sadequain.

Around the Hall are two lawns originally known as ‘Queen’s Lawn’ and ‘King’s Lawn’, which were added in 1887-88 by Mr Benjamin Flinch. Originally the statues of Queen Victoria and King Edward (both of which have now been removed) adorned the garden. These lawns were renamed as Bagh-e-Jinnah (Jinnah Garden) after independence. These lawns have played host to a lot of evening entertainment as families would lounge and picnic in its greens, and flowers shows would be organised.

It is a pity that due to security concerns, as well as the insistence of the US Consulate, which faces Frere Hall, the park today has largely been declared off-limits to the public. Yet, Frere Hall and its sprawling lawns are one of the few pieces of imposing architecture which we Karachiites are proud to view in a city otherwise dominated by pollution and unimpressive buildings.

So next time you pass by Abdullah Haroon Road, ignore the police cars and barricades and do spend a minute or two in appreciating the splendour of this fine building.

Karachi: history quiz

Karachi Through The Ages

ONE: Many historians claim that the ancient city of Debal was where Karachi is located today. It was ruled by Raja Dahir, who captured the boats that were carrying valuable gifts and Abyssinian slaves, which were sent to Caliph Waleed, from the king of Sri Lanka. Hajaj bin Yusuf, the Governor of Iraq, was so infuriated that he dispatched troops under his nephew, who defeated Raja Dahir. Name the 17 year old Arab General?

TWO: The Quaid-i-Azam decided to make Karachi the capital of Pakistan because he thought that Karachi was a natural seaport and had a large airport. Lahore was too close to the Indian border and was, therefore, quite vulnerable. State true or false: no one was sure till the last moment whether Lahore would be a part of India or Pakistan.

THREE: At a time when the forces of the East India Company occupied Karachi its population was in the proximity of 15,000. It was less populated than many cities of the subcontinent, such as Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Chennai and Lahore. Today only one city is more populous than Karachi. Name?

FOUR: In February 1939 the East India Company occupied Karachi without facing any resistance from the natives. How did the invaders arrive: from land or the sea?

FIVE: The first railway tracks were laid down in the subcontinent between Bombay (as it was known until very recently) and Thana, now a part of metropolitan Mumbai. Which two towns were connected by railway when it was introduced in Sindh?

SIX: Unlike Lahore and Mumbai, Karachi did not have a population of cricket buffs, until after Partition. Now the question: where were international matches played in the city before the National Stadium was built?

SEVEN: Opened to shoppers in 1889, Empress Market, one of the most splendid specimens of colonial architecture, was designed in what is called ‘Domestic Gothic Style’. Who was it named after?

EIGHT: At the confluence of I.I. Chundrigar Road and M.A. Jinnah Road is one of the many towers that were built by the British in the subcontinent during the Raj – Merewether Tower. It was completed in 1892. What was its original name?

NINE: Karachi’s trams, which were withdrawn a few years after Partition, were ugly like the trams that ran in old Delhi, but with one difference, while the latter, like all other trams in the subcontinent, were powered by electricity, the ones in Karachi were run on another source of energy. Can you guess which?

TEN: Some names could not be replaced such as Guru Mandir and Golimar. The public didn’t accept the new names – Sabeel Wali Masjid and Gulbahar. On the other hand, some new names took time to be on the lips of the people. Examples: I.I. Chundrigar Road and Abdullah Haroon. What were their old names?

ANSWERS:

(1) Muhammed bin Qasim (2) True (3) Mumbai (4) They sailed to Karachi (5) Karachi and Kotri (6) Karachi Gymkhana (7) Queen Victoria (8) Merewether Memorial Tower. It was named after the ‘Commissioner-in-Sinde’, Sir William L. Merewether (9) Diesel (10) McLeod Road and Victoria Road. — Compiled by AN.

Karachi: Historical Quarters

Preserving cultural assets Excerpted with permission from

The Historical Quarters of Karachi

By Yasmin Cheema

Oxford University Press, Karachi

185pp. Rs595

The protection of historic architecture and architectural monuments in the urban areas of Pakistan has been grossly neglected. Consequently, historical buildings and humbler dwellings of artistic merit in urban centres and small towns are failing apart or being rebuilt haphazardly. The latter is caused mainly by lack of training in conservation and by non-qualified conservationists trying to restore ‘them back to their ‘Old Glory’.’

Karachi’s old historic fort still exists in the form of streets and mohallas, embellished with a number of dharamshalas, temples, mosques, shrines, and its traditional bazaars. The older suburbs of Karachi survive with some retaining their winding streets, and open squares. The 19th and 20th-century British quarters, which flourished with commercial/port activities, are largely intact. These boulevards, streets, quarters and richly embellished stone buildings from that period, are comparable to the 19th-century historic areas of other cities around the world, such as Cairo, Istanbul, Delhi, etc.

Since Independence, the historical core of Karachi has been subjected to functional pressures, which it is inherently incapable of confronting. These pressures are partly due to the rapidly growing port mega-city of Karachi, now about 35 times the population and eight times the area of the pre-Independence historic core.

Growing poverty, the infiltration of low-grade commercial enterprises, lack of a socially responsible community ethos and the complete obscurity of historical Karachi from the attention of authorities responsible for urban administration, have resulted in widespread dilapidation of its buildings. This is accompanied by a gradual loss of cultural traditions in the historic quarters and neighbourhoods, including cultural practices and behaviour patterns that had continued from the past. These include ritual practices, entertainment, eating, selling of traditional crafts, the operation of traditional bazaars and British period market places.

The recognition of the historic city’s cultural significance and its future within the overall urban system is totally ignored by all the city development agencies, resulting in the lack of a policy framework that could guide decision-making relating to future land use, traffic improvement, the control of certain incongruous economic pressures on the historic quarters, while facilitating those which will reinforce cultural continuities, reviving selfidentity and pride of their residents.

The present policy for protection of Karachi’s vast cultural heritage is an ongoing process of identifying and listing of protected buildings under the Sindh Cultural Heritage Act 1994. These buildings, scattered within the historic tissue, at a substantial distance from each other, are often a part of 19th and 20th-century stylistically rich building groups, forming a neighbourhood which is part of the 24 miles of pre-Independence Karachi’s historic fabric. If this policy continues, isolated buildings, now a part of ongoing tangible and intangible cultural traditions will be transformed into dead historic monuments, squeezed between rows of ugly high-rise commercial plazas. The second more serious scenario is that of displaying old buildings as antiquities in newly developed areas.

The historic core of Karachi is therefore, in acute danger, and if the present policies and practices of safeguarding its heritage persist, only a fraction of historic Karachi will remain as a measure of cultural heritage for the coming generation.

The goal of the study on which this book is based was to initiate a process for the preservation of Karachi historic city’s tangible and intangible cultural assets, by revalorisation, rehabilitating and reinforcing its tradition and physical/socio-cultural characteristics as a distinct urban district of national cultural significance, with high historic, environmental and cultural qualities. The objectives are to establish that the historic core as a whole is of national cultural significance, instead of isolated individual buildings; and have this aspect of historic Karachi recognised by politicians, development agencies, professional bodies and the citizens of Karachi. It also seeks to identify the nature and extent of tangible and intangible cultural assets of the area.

The subsequent chapters also propose necessary actions for receiving, rehabilitating and safeguarding these assets, by suggesting possible policies for controlling expansion of incongruous low-grade commercial activities, while facilitating those that encourage continuation of tradition and cultural linkages. The study identifies historic neighbourhoods, and building complexes of high cultural significance, which deserve intensive conservation efforts.

There is a need to work with communities rich in historic residential fabric, with an aim to facilitate better living conditions, through both physical up-gradation and reinforcement of social networking. This can lead to the residents’ greater identification with their neighbourhood, and ultimately feeling responsible for its maintenance.

The historic quarters of Karachi today form part of a larger metropolitan area. The development and growth of metropolitan Karachi is one of the major factors of the changes confronted by Karachi’s historic districts. Therefore, it is imperative to study the quarters in the context of a larger metropolitan growth.

Given the constraints of time and resources it was not possible to cover the entire 9.26 sq. miles of the historic quarters. Therefore, only one complete quarter and parts of three others, have been investigated within the framework of overall growth and development of Karachi metropolitan areas, and the changes taking place in neighbouring quarters.

Two quarters, i.e. Old Town Quarters and Serai Quarter existed before British Rule, while the British developed the Jail or Wadhumal Quarter and Ranchore Quarters. These quarters, located at a distance from each other were selected for study, firstly, as samples of British and pre-British development, secondly due to their original function and thirdly for the changes they have undergone and their role in the new metropolitan Karachi.

The Old Town Quarters, now called Mithadar and Kharadar, is the starting point of the oldest part of the city. The three other areas included in the study are located close to the Old Town Quarters and form a progressive physical link to it. This is taken as the starting point of what is presumed to be an ongoing study, which can be carried out for the rest of Karachi’s historic core.

Karachi’s origins date back to the Vedic Period, but it gained prominence in 1729, when it emerged as a major port of Sindh, having replaced the earlier busy maritime exchange centres, Daibul (Bhambor), Thatta, Lohari Bundar, Dua Jam and Shahbad. These ports had become inoperable after the moving of the rivers which caused silting and flooding.

Karachi’s establishment as a port is contributed to Hindu merchants of Karak Bunder (Hasan: 1988, 7), but its development, as a major western port of India is attributed to the Talpurs, who conquered it in 1729.

The British recognising the strategic position of Karachi vis-à-vis its location to the West, started its investigation in the late 17th century (Khuro: 1997, 14). In 1839, they conquered Manora/ Karachi, (Baillie: 1890, 17) and by 1843 they had wrenched away all of Sindh from the Talpurs and declared Karachi its provincial headquarter.

According to Baillie, at the time of the Talpur conquest of Karachi, it was a small mud fortified city located along the Lyari River (Baillie: 1890, 21). It soon became a flourishing maritime trade centre, which developed further with the support of the British (Khuro: 1997), and the political tranquillity of the Talpur rule. As the city grew in population, it started to spill over the city walls, and several suburbs emerged around the walls. In 1799, the population of Karachi was 10,000 and by 1813 (Lari: 1996, 11), it had increased to 13,000. By 1830, it was 15,000 (Baillie: 1890, 29), and the suburb outside the city wall had expanded greatly. It consisted of what are now called Napier, Market, Bunder, Rambagh, Serai, Lyari and Machee Miani Quarters (Baillie: 1890, 83). A road called Rah-i-Bunder was built, during Talpur rule, to link the Karachi port to Kafila Serai, a terminal for camel caravans, located at the southern boundary of the city.

The British having conquered Karachi, set up their camp one mile from the old native fort/city, at south west of the Hindu religious Rambagh precinct (Hasan: 1986, 8). In 1843, at the British declaration of Karachi as the provincial capital of Sindh province, Sir Charles Napier, started to plan the expansion and development of the city and to improve the harbour and its facilities, (Baillie:1890, 45By 1854, when Napier left Karachi, the British Cantonment had been established a mile north-east of the earlier British army camps. The only buildings constructed during Napier’s tenure were a few scattered colonial bungalows, offices, a few clubs, and some army barracks (Khuro: 1997, 36).

Frere’s plans for the city were more ambitious than those of Napier, comprising of a harbour improvement scheme, city road layout, canal construction and establishment of a railway system to connect Karachi port to the inland cities (Baillie: 1890, Ch. 5, 6, 7). These developments were instrumental in Karachi’s rapid population growth. Therefore, in 1850, Karachi’s population rose to 16,773; by 1853 it was 22,224. Of this population 13,769 inhabitants lived in the old port/city and 8458 in the suburbs. While the native city and its port and suburbs flourished, the Saddar and Artillery Ground were the first quarters developed by the British in 1839 (Lari: 1996, 139,149). Once they became well entrenched politically, the British started to establish new areas for themselves, and develop the existing native areas. With the establishment of Karachi Municipality, the developments of the city became rapid and more regulated. The infrastructure of the existing quarters was improved, and new quarters delineated.

Around mid-19th century, the quarters next to the ‘native city’ were developed for the growing native population, which included the Bunder Quarter, Market Quarter, Napier Quarter, and Lyari Quarter. The relatively vacant quarters south west of these, the Jail Quarters and Ranchore Quarters emerged as one of the civic centres by late 19th century.

Books & Authors reserves the right to edit excerpts from books for reasons of clarity and space.

Karachi’s heritage

On the eve of independence, the population of Karachi numbered 450,000 people; since then the population has increased by 2,500 per cent and the land area by 1,600 per cent. The historical quarters treated in this survey have been surrounded, overwhelmed by urban sprawl, and neglected. To the casual observer or, in this reviewer’s case, first-time visitor, these areas appear to be lost causes, full of commercial vitality but doomed to decay. The grand old public and private buildings cast only shadows of their former selves and in many cases are merely skeletal structures. How long before they come crashing down or are demolished to make way for flyovers or more modern interlopers?

Remarkably, such suppositions are premature, although time is running out. So argues Yasmin Cheema on behalf of a team that has surveyed in detail four primary areas — Old Town, Serai, Wadhumal Odharam and Ranchore quarters — ‘the British period civic centre and commercial hubs of the city [that] now form the historic core of the new Karachi Metropolitan Area.’ Charting physical change and environmental factors of existent structures including number of storeys, construction materials, present and original functions, ownership and usage, water supply and sewage, electric supply, garbage collection, traffic circulation, and building conditions, Cheema lays out a plan of action for revitalising these areas via rehabilitation and reconstruction that preserves the unique flavour of Karachi’s historic heart.

This quantitative survey is designed primarily for urban planners who may yet be persuaded to examine national, provincial and municipal statutes described in order to seize civic power back from the various mafia-style forces that seem to dictate urban growth. Those looking for a descriptive survey of Karachi’s obvious rich architectural history will have to look elsewhere. Perhaps that is a task that Cheema and her associates should undertake next. Cheema argues that Karachi’s heritage should not be consigned to historic books sitting on coffee tables. Yet in cities like Cairo with similar strains, active coalitions of preservationists have inspired a resurgent nostalgia for pre-independence belle époque architecture in part through the publication of photographic essays devoted to structures once viewed through harsher historical lenses as colonial imports and imitations.

Is it too late to stop speculative development and illegal encroachment? ‘The physical fabric of these quarters is intrinsically unsuitable for the functions they have been called upon to perform progressively over the last 75 years… the policies at the city level of mass transit and the Lyari Expressway are a glaring example of a lack of appreciation for the fine grain quality of the historic quarters and the need for their rehabilitation… the city administration, the owners in front of whose property the encroachment takes place, and the encroachers themselves participate in the process and benefit from it.’ Such conclusions leave little room for hope. Yet Cheema’s insistence that the historic quarters still have potential for a vibrant and rich residential life should be enough to make civic leaders and concerned citizens pause before shrugging off the next bulldozer and wrecking ball.

— Reviewed by Joel Gordon

The writer is a professor of history at the University of Arkansas, USA. He recently visited Karachi.

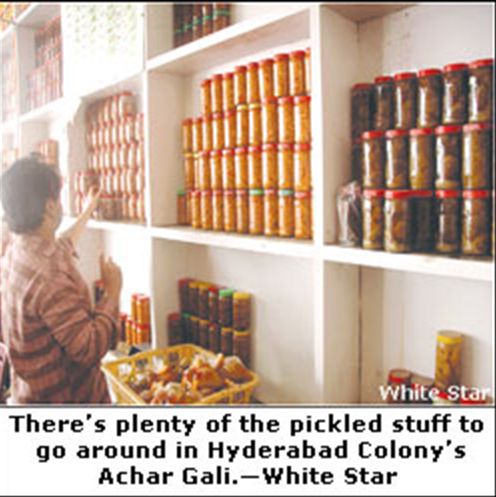

Karachi: Hyderabad Colony’s Achar Gali

The achar culture

By Qasim A. Moini

KARACHI’S incredibly cosmopolitan nature can be gauged from the number of cuisines that are on offer across its vast sprawl. Suffice to say, the city is a food lover’s delight, and its cuisine has been influenced by the many different cultural and ethnic groups that have settled here over the years.

Within its innumerable localities can be found food for all tastes and all income brackets. Many of the city’s neighbourhoods contain renowned haunts where foodies can satiate their appetites with delights rarely found in other areas. One of these is Hyderabad Colony’s Achar Gali.

The fist thing that hits you as you enter Achar Gali – located in a sleepy lane hidden away from the incessant madness of city life near, of all places, the Karachi Central Prison – is the pungent aroma of achar. As you get closer, you notice that there is not one, not two, but rows upon rows of the tangy, tasty pickled stuff waiting for you. For this lane – barely a kilometre long – is the general headquarters of traditional achar and other snacks from Hyderabad Deccan.

Achar Gali transports one to another world. Apart from the many food items that abound in its shops, the air here is heavy with the scent of old world tradition. And one of the most delightful aspects of visiting the Gali is the distinctive Hyderabadi dialect of Urdu. Though perhaps not as pronounced as in Hyderabad itself, for the ear attuned to the nuances of language, it definitely stands out. Still, it is the food that sets apart Achar Gali from Karachi’s other quaint neighbourhoods.

A clutch of about half a dozen shops, bursting at the seams with countless colourful jars of achar, is the star attraction here. I walk up to one with an impressive array of pickled produce, which also has a set-up for hot snacks. As it’s lunchtime, a group of young office workers are huddled around a table, wolfing down what principally appear to be pakoras and samosas, washing it down with cold drinks. I approach the chap behind the till to enlighten me about the finer points of achar and Hyderabadi cuisine in general.

“Look, if you want to write on food and drink, go visit some food street. Achar is not a food item; it is a saqafat (culture),” comes the reply.

Slightly stunned, I meekly proceed to gather some more facts on the history of Achar Gali, this time treading more carefully lest I offend any more gastronomic sensibilities.

The shopkeeper tells me he isn’t very good with dates and other details, but from what he remembers, immigrants that came from Hyderabad Deccan after Partition settled in three localities of the city: Bahadurabad, New Karachi and Hyderabad Colony. Though not aware of the lane’s proper name, he tells me all and sundry simply refer to it by its popular name: Achar Gali.

“We stock over 25 different kinds of achar. All the recipes are my grandmother’s. She started off on a much smaller scale. Mine is the third generation that has been involved in making achar,” he says, as containers of the tangy stuff surround him.

One of varieties tasted by this writer was mixed achar, which, along with the usual suspects, also contained sliced lemons. One must say it was a lot more pungent than the brand-name stuff available in the market, but a jarful at home is a welcome addition to kichri, parathas or a plateful of hot daal. Adrak (ginger) achar was also tried; suffice to say, it is an acquired taste, but as I was informed, it’s supposed to be darned good for health. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg; quite frankly, this writer did not have the stomach (pun intended) to try the other 23 varieties in one go. There’s always next time.

“Hyderabadi achar is distinct from Hindustani and Shikarpuri achar. It is tangier, while bhagar and pukka oil is used during the preparation,” the shopkeeper informs me with a hint of pride. Aside from achar, other food items of repute available at the Gali include Hyderabadi Dahi Baray, which I am told resemble kari, along with the luscious luqmi.

This is a square version of the samosa, and I, for one, am convinced that it deserves special mention. With a filling of savoury minced meat enwrapped within flaky dough, the stuff just melts in your mouth. Ketchup, raita or your favourite chutney just add to the experience.

However, a piece on Achar Gali would be incomplete without mentioning its delicious deserts. Leading the pack is the calorie-laden, heaven-sent double ka meetha, along with the equally divine khobani (apricot) ka meetha. The locals tell me kaddu (pumpkin) kheer is not to be missed either.

A friend who used to frequent the Gali says the number of food shops has decreased over the years. It would be a shame if this cultural asset was to disappear to make way for a gaudy shopping mall, or worse still, a multinational fast-food franchise.

Karachi: Jahangir Kothari Parade

Thanks again, Mr Kothari!

By Saima Shakil Hussain

Mea Culpa. I admit my fault. Whenever I saw tourists in Karachi or heard someone from out of town ask what places there were to visit here, I was the first to let out a guffaw and exclaim, “Nothing. There is nothing to see here. Go somewhere else.”

Oh sure, there is the Quaid’s Mazaar and Mohatta Palace Museum, but there is no place in this city that could be on anyone’s ‘top ten places to visit before I die’ list. Right?

Wrong. The cynic in me got her upcommance unexpectedly one weekday night on a family outing after dinner when we decided to go for a walk in the relatively new park along Clifton beach. Attached to the historic Jahangir Kothari Parade -- one of the very rare historical monuments that have been preserved by the city -- the 130-acre park is a majestic sight to behold, especially at night.

Well-lit, thanks to a combination of lighting towers, vision floodlights and footlights, the expansive green space gives a sense of vastness that is in itself something so precious and unique in this densely-populated city. A fair number of families, couples and groups of young men were seen walking along the pathways, sitting on the grass or on the numerous stone benches scattered around the park. Food and drink are apparently prohibited on the premises, which would explain its spotlessly clean appearance. Nevertheless, a large number of garbage cans have been provided optimistically for those who cannot help but generate litter -- a nuisance which is endemic to our corner of the world.

It does one’s civic sensibilites proud to see the Jehangir Kothari Parade today.

The site, originally owned by eminent Karachi citizen Sir Jehangir Kothari, was gifted by him to the city in 1920, along with a generous donation of three lac rupees. Over several decades it fell into a state of utter dilapidation due to official negilence and public disregard. Someone finally took notice thus rennovation work began in 2005, and was actually completed -- in what would appear to be record time -- in January 2007. Which goes to show that if the city government puts its mind to it, there is nothing that cannot be done to uplift this city. Perhaps they could start by spending less money on promotional ads on television and more on such worthy projects.

Today, the bandstand located on the western end of the 86-year old parade acts as a beacon for visitors to the park which also houses the Lady Lloyd Pier. Designed at a right angle to the parade walkway and extending over 1,200 feet towards the sea, the pier is named after Lady Lloyd, wife of the then Bombay Governor Sir George Ambrose Lloyd, who inaugurated the walkway in 1921. Legend has it that it was Lady Lloyd who, during a visit to Clifton, was captivated by the Karachi’s sea breeze and had expressed the desire to be able to walk to the sea, and thereby provided the inspiration for the project.

What stands out and is most commendable about the entire project is the effort that has been made to remain as faithful to the original architecture as possible. Conservationists would disagree with this, for the uniformity makes it difficult to distinguish between the historic monuments and the barely year-old development surrounding them.

Lasbella stone has been used for renovation of the parade and construction of additional lawns, paths and walkways. Admittedly inferior in quality to the original Jodhpur sandstone (Chattar), it is, however, similar to it in appearance. The Mahadev Mandir which is now located within the park grounds has also been renovated and remains open to Hindu worshippers. Even the original plaques mounted on the walls 86 years ago have been retained.

It is from one of these plaques that one learns the original name of the recreational site: Rupchand Bilaram Park. So while the new name, Bagh Ibn-i-Qasim, is quite stately and commenable, it would be a shame to erase the past and diminish the contribution of Karachi’s Parsi and Hindu citizens. Some might argue that for political reasons the original name cannot be maintained but it’s the 21st century for heaven’s sake! The metropolitan city should proudly display its multi-religious and mutlicultural heritage.

Its history is interminably linked to the many philanthropists who set up educational institutions and constructed landmarks here before partition by ignoring them and choosing a ‘convenient’ version of history the authorities are perpetrating a grave injustice indeed.

Karachi: Khadda Market

Let’s do lunch… at Khadda Market

By Shagufta Naaz

THE name may not sound very promising but Khadda Market is one of the most happening places in Defence right now. A maze of narrow, twisting streets that can have you going round in circles, the market is home to apparel outlets, music stores, mobile phone shops and, best of all, two well-stocked second-hand bookshops.

And then there is the food.

Unlike Boat Basin which lines up all its offerings in full view, Khadda Market is a realm of exciting nooks and crannies, all waiting to be explored. So what are you waiting for? It’s almost time for lunch.

Our first stop is the place that made Khadda Market famous – the original Chatkharay. Starting off as a chaat and snack outlet, Chatkharay soon came up with its winning formula – a restaurant that offers a taste of ‘home-cooked’ meals. By keeping the food simple and offering a limited but different menu every day of the week Chatkharay has successfully brought alive the concept of ‘just like home’. Qeema hari mirch, daal and chicken kofta are some of the hot favourites, served with fresh, fluffy chappatis, just like mom used to make.

Inspired by Chatkharay’s success, a me-too establishment by the name of Hyderabadi Chatkharay, welcomes you just a few steps down the road. While not quite at par with the original in terms of ambience, Hyderabadi Chatkharay has, nevertheless, managed to carve a niche for itself by offering a slightly different menu – paya and pasanda for lunch anyone? Frozen Hyderabadi goodies like bhagaray baingan and mirchon ka salan are available for take-away.

Both these places offer Karachi’s favourite food – biryani, of course – but true aficionados always go to the expert. In the case of Khadda Market that happens to be Indus. While Jeddah Biryani at Boat Basin jolts the senses, Indus Biryani tantalises your taste buds and wakes them up. The spicy, garlic flavoured raita is an added plus.

For those who crave a carb fix, there’s no better place than One Potato Two Potato (shouldn’t that be two potatoes?), the hangout that makes magic with French fries. Smothered in the dip of your choice (cheese and garlic mayo are the top favourites), the fries are a meal in themselves, but you can always order a burger or a hot-dog to go with them. For serious potato lovers, a tub of mash and bangers from, well, Mash and Bangers is a must. A creamy concoction of mashed potatoes, chunks of sausage and meat (or veggies if you prefer), mash and bangers probably has enough calories to sustain a family of four for a week. Of course, you can always go back on Atkins tomorrow.

For a taste of barbecued delights, Hot and Spicy is just around the corner. Credited with elevating the humble kabab roll to the status of a gourmet meal (whoever thought of adding cheese and mayonnaise to a roll before?), Hot and Spicy is perhaps the most successful of the Khadda Market eateries and offers the most extensive menu – from 72 types of rolls to all kinds of burgers, sandwiches, handi, karhai, Chinese and almost everything else that you can think of.

If you’re looking for something exotic, there’s Olive Grill and the Bistro. A relative newcomer to the Khadda Market eating scene, the Olive Grill offers a cosy ambience and an ambitious menu, featuring Thai, Burmese, Arabic, Italian and Mexican. Otherwise stroll over to Ming Court, a survivor of the grand era of Chinese restaurants, where the cool, dimly lit interior and peaceful ambience (sans the jarring music that is de rigueur at all ‘fashionable’ restaurants) set the tone for a leisurely, multi-course meal.

Another pleasant place to while away the hours is Café Coffee Day, Khadda Market’s first coffee shop. With a good selection of sandwiches and the common flavours of java, Café Coffee Day is the only place where a sandwich and cappuccino don’t cost as much as a three-course meal.

For those who want something wholesome yet delicious, there’s Agha’s – not the supermarket – the juice shop. Defence residents who, for years, braved the perils of a drive to the other side of town were ecstatic to find this milkshake magician right at their doorstep. If mangoes are out of season, don’t worry because Agha’s offers everything from chikoo and falsa to strawberry and lychee.

If you have room for dessert, grab a doughnut from the French Bakery or a few chocolate tarts from Hobnob. Now all you need is a way to stay awake during those afternoon meetings. Bon apetit!