Lata Mangeshkar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From: February 7, 2022: The Times of India

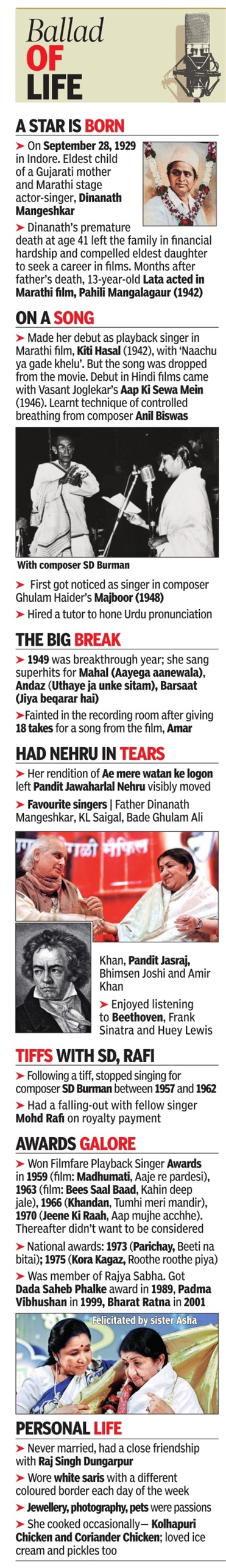

See graphic:

Lata Mangeshkar, A timeline

Contents |

An overview

1929-2022: A brief biography

Lata Mangeshkar, known as the 'Nightingale of India', is one of the most versatile singers in the Indian film industry. Lata was born on September 28, 1929, to classical singer and theatre artist Pandit Deenanath Mangeshkar and Shevanti in Indore, Madhya Pradesh.

She is the eldest of her four siblings, Meena, Asha Bhosle, Usha and Hridaynath Mangeshkar.

Lata Mangeshkar started her singing career at the age of 13 with Marathi movie 'Pahili Mangalaagaur' in 1942.

One of her first major hits was "Aayega Aanewaala," a song from the 1949 film 'Mahal,' lip-synced on screen by the late actress Madhubala.

Mangeshkar was only 20-years-old when she became the most sought after playback voice in the Hindi film industry. A decade later she sang the soulful number, Aaja Re Pardesi for Bimal Roy’s 1958 reincarnation saga ‘Madhumati’ which starred Vyjayanthimala in the lead.

K Asif’s magnum opus ‘Mughal-E-Azam’ which released in 1960 featured, Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya. While Madhubala conveyed the defiant Anarkali’s emotions, it was Mangeshkar’s voice which depicted the passion and rebellion. The same year also saw the release of the evergreen number, Ajeeb Dataan Hai… Be it Piya Tose Naina Lage Re, from the Waheeda Rahman starrer ‘Guide’ which released in 1965 or Hothon Pe Aisi Baat, featuring Vyjayanthimala, Mangeshkar lent her voice to every leading lady of the 1950s and the 60, the period considered to be the golden era of Hindi cinema.

Mangehskar was known for classical, folksy and even haunting numbers. But she surprised her fans when she sang Baahon Main Chele Aao, a sensual number from the 1972 film ‘Anamika’ composed by R D Burman.

The same year also saw the release of Kamal Amrohi’s ‘Pakeezah’. Actress Meena Kumari’s swan song in which essayed the role of a Lucknowi courtesan had some evergreen hit numbers.

Lata Didi, won her first National Award in the Best Female Playback singer category for the song Beeti Na Beetaye Raina, song from Gulzar’s 1972 film ‘Parichay’ … Two years later she bagged the National Award for the second time for the number, Roothe Roothe Piya from the film ‘Kora Kaagaz’, Gulzar’s 1977 film ‘Kinara’ featured this song composed by R D Burman. As the lyrics suggest Mangeshkar’s voice is what gave her identity and still does.

While the 80s saw Mangehskar deliver one hit after another, the 1990s saw the singer collaborate with her brother Hridaynath Mangeshkar for Gulzar’s ‘Lekin’. This haunting song, Yaara Sili Sili won Mangeshkar her third National Award in the Best Female Playback singer category. While Lata Mangeshkar can evoke every emotion with effortless ease with her velvety voice,

few can evoke the patriotic fervour as effectively as her. Aye Mere Watan Ke Logon, the song which commemorated Indian soldiers who laid down their lives during the Sino-Indian war is believed to have reduced late Prime Minister Jawarlal Nehru to tears. Mangeshkar has sung for almost all the Yash Chopra films including Chandni in 1989, Lamhe in 1991 Darr… 1995 film Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, Dil To Pagal Hai in 1997, among others… In the late 90’s and 2000’s Mangeshkar collaborated with AR Rahman, for hits like Dil Se, Zubeida, Lagaan and Rang De Basanti …

Lata Mangeshkar has received several awards and accolades during her eight-decade-long career, including the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1989, India's highest civilian honour, Bharat Ratna in 2001, three National Awards and 7 Filmfare Awards. The Indian government honoured her with the Daughter of the Nation award on her 90th birthday in September 2019. Lata Mangeshkar’s voice has been a part of every Indian’s life for the past 8 decades. Her repertoire of work is unmatched and she is undoubtedly the golden voice of the country.

B

Ambarish Mishra, February 7, 2022: The Times of India

Lgroomed in the art of playback singing—diction, pronunciation, voice modulation and breath control—by Master Ghulam Haider, Anil Biswas and Naushad Ali. She went on to team up with composers as varied as C.

Ramchandra, Shankar-Jaikishan, S D Burman, R D Burman and A R Rahman, and found favour even with purists like Madan Mohan, Roshan, Khayyam, Sajjad Hussain, Jaidev, Vasant Desai, Salil Chowdhary, and Hridayanath whose creations were steeped in Indian ragas.

The appeal partly lay in her incredible vocal range—it extended beyond three octaves, allowing collaborators to experiment with form and content. Anil Biswas would say she inspired them to work on innovative musical phrases. “Hindi cinema was looking for a pan-Indian voice to suit female leads of varying extracts—Vyjayantimala and Hema Malini came from south, Sharmila Tagore and Raakhee from Bengal, while Nutan was a Maharashtrian. Mangeshkar answered the need,” said film chronicler Veerchand Dharamsey.

Pointing out that her 1947 debut coincided with Partition, Prakash Joshi, a musicophile with a collection of 4,000 Lata songs, said her songs helped heal the wounds of communal frenzy. “ ‘Hawa mein udta jaaye’ (from Barsaat) was enough to put a smile on India’s lips, replacing horror with hope,” he said. Born in Indore on September 28, 1929, to Dinanath and Shevanti Mangeshkar, she was trained in classical music by her father, an actor-singer from Goa, who owned a drama company. Eldest among five siblings, her passion for singing was evident as early as age four.

Master Dinanath’s death in 1945 altered her life’s course. She joined Prafulla Pictures, a film company helmed by produceractor Master Vinayak Karnataki and became the family’s sole breadwinner at 14. Hindi film composer Ghulam Haider, a Lahore migrant, was quick to spot her potential. When producer S. Mukherjee, whose ‘Shaheed’ was on the floors, rejected the thin voice which, he said, wouldn’t suit the female lead, an angry Haider stormed out of Mukherjee’s Filmistan studio in Goregaon with Lata in tow, but not before warning the movie moghul that his protegee would become a superstar. “That afternoon Master-ji and I trekked to Goregaon railway station. Master-ji said he would find me an opening in Bombay Talkies. The platform was deserted. We sat on a wooden seat. Tapping lightly on his 555 cigarette tin, he taught me a song,” Mangeshkar told TOI in a 1998 interview. ‘Dil mera tora,’ from ‘Majboor’ brought instant success, and was followed by ‘Aayega aanewala’ from Mahal (1949). As the 78 rpm record sleeve of Mahal didn’t carry her name, radio stations were flooded with calls from admirers eager to know the singer’s identity. Between 1947 and 1951, her popularity soared. This phase coincided with singing star Noorjahan’s migration to Pakistan and the gradual fading away of Suraiya.

A moment of glory came when she was invited to a midnight congregation at Shiva ji Park on May 1, 1960 to mark the formation of the state of Maharashtra with a Marathi prayer song. Three years later, her voice rang out at a rally in Delhi to raise funds for families of soldiers who died in the Indo-China war. Nehru fought back tears as he heard ‘Ae mere watan ke logon. ’ After the event he met her and said, ‘Beti, aaj tumne mujhe rula diya” (You brought tears to my eyes today). ’

Mangeshkar reigned in the 1970s-’80s despite drastic changes in taste. Languorousilting tunes gave way to heavy orchestration and fast beats. She was quick to adapt, crooning for composers half her age (Rajesh Roshan, Bhappie Lahiri, Jatin Lalit, Raam Laxman), as also with GenNext singers S. P. Balasubramaniam, Sonu Nigam, Suresh Wadkar. Though she cut down on assignments, her ‘Dil deewana bin sajna ke’ from Maine Pyaar Kiya set the mood for the vibrant 1990s. She took Youngistan by storm with ‘Tu mere saamne’ (Darr), ‘Gori hai kalaiyaan ‘ (Aaj Ka Arjun), ‘Yaara sili sili’ (Lekin), ‘Didi tera dewar (Hum Aapke Hain Kaun), ‘Chhai chhappa chhai’ (Hu Tu Tu). Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge became a cult, post-globalisation film, reviving romance with frothy numbers like ‘Mere, khwabon mein jo aaye’, ‘Mehndi laga ke rakhna’ (the Lata-Udit Narayan duet is played at wedding receptions even today) and ‘Tujhe dekha toh yeh’ (with Kumar Sanu). ‘Luka chuppi’, a moving piece, from Rang De Basanti, is considered her swan song, a sort of grand finale to an epic life.

Early life

Meri Awaz Hi Pehchan Hai

By Sibtain Naqvi

Everyone has their favourite Lata moment. Mine was in a heavy traffic jam in Karachi in searing heat. As rivulets of sweat coursed down my spine, I wearily turned on the radio and a sweet melody floated on the airwaves. Lag Ja Galay, the quintessential Lata song from the film Who Kaun Thi (1964), floated on the airwaves and at that moment the heat, smog, blaring horns and the loud curses of frustrated drivers all became distant. Music can indeed sooth the savage beast as in this case it did the irate driver.

Nobody including Pandit Dinanath Mangeshkar could have predicted that his eldest offspring, Lata, born on September 28, 1929, would be given the title of ‘the Nightingale of India’.

When the seven-year-old played Narad to her father’s Arjun in Sholapur, little Lata brought the house down with her acting and singing, showing glimpses of the brilliance which would later light up the celluloid. She took her first music lessons from her father at the age of five and the recitals left a strong impression on her, as did the songs of K.L. Saigal, her favourite singer and idol.

According to a popular story, when little Lata came home after watching K.L. Saigal’s Chandidas directed by Nitin Bose, she declared that she would marry Saigal Sahib when she grew up. Hence began Indian filmdom’s most enduring love story between Lata Mangeshkar and Indian film music.

She started her Hindi singing career when she moved to then Bombay (Mumbai) in 1945 and played a minor role alongside Noor Jehan in Master Vinayak’s first Hindi-language film, Badi Maa. She began by imitating Noor Jehan, who with her heavy voice was then the most popular singer. The lyrics of songs in Hindi movies were primarily composed by Muslim poets such as Kaifi Azmi and Janisar Akhtar and contained a higher proportion of Urdu words. Dilip Kumar is said to have once gently chided Lata about her Maharashtri accent while singing Urdu songs. To overcome this predicament she took lessons in Urdu from a maulavi named Shafi.

Lata’s first major hit came in 1949 with Kamal Amrohvi’s film, Mahal. The song was Aayega Aanewala, composed by music director Khemchand Prakash and lip-synced on screen by actress Madhubala. The Venus-like Madhubala crooning for her lover in Lata’s melodious voice created such an everlasting piece of cinematic history that even today, nearly half-a-century later, it is clear why the song is such a sensation.

Moving sentiment is the hallmark of any Lata song. It is her ability to reach inside the lyrics, to probe the nuances of the moods, skillfully balancing changing cadences that make her so much in demand. She brings adaptability across generations and even within the lifespan of an artiste. Think of the wide-eyed child woman appeal of Dimple Kapadia in Hum tum aik kamray mein bundh hoon from the film Bobby and you think of Lata; recall the mature, sensitive Dimple in Yaara seeli seeli from the film Lekin and you still think of her. Trends have changed, technology has come to play a crucial role yet the classic has remained with Lata.

Yash Chopra rightfully says, “Usually, it is an artist who follows the art. But in Lataji’s case it’s the art that has followed her.”

Many compositions were written only for her voice. When Naushad composed Mohe Panghat Pe for the epic Mughal-i-Azam, he called Lata aside and said, “I’ve created this tune only because you are going to render this song. No one else can do justice to this composition.”

Lata was understandably the preferred choice for the leading ladies of her time. From Madhubala to Madhuri, all owe their biggest musical hits to her voice and while they themselves have phased out, Lata continues to fire romance, pain, hope and nationalism with her soulful renditions. No wonder the late Bade Ghulam Ali Khan once exclaimed, “Kambakht toh kabhi besuri hi nahin hoti!” (Dammit, she never sings out of tune).

Still, the living legend’s career has not been without controversy. It’s ironic that once Noor Jehan immigrated to Pakistan and Surriya and Shamshad Begum retired, her biggest rival was her sister Asha Bhosle. With S.D. Burman, Lata had a blow hot-blow cold relationship and the main beneficiary of this was Asha.

Before 1957, S.D. Burman chose Lata for his musical scores in many films including House No. 44 (1955) and Devdas (1955). However, they had a fallout in 1957 and Lata did not sing Burman’s compositions till 1962, with the result that Asha and to a lesser extent Geeta Dutt took over. Asha also became the chosen singer for O.P. Nayyar and for sometime the two sisters’ relationship went through testing times.

Lata’s relationship with most of her male colleagues was cordial. Mukesh, Manna De, Hermant Kumar all worked with her to give memorable numbers. With Kishore Kumar it was especially so, ever since she assumed the worst and mistook him for a lecher following her on her way to meet Khemchand Prakash for whom she sang Aayega Aanewala.

However, with the colossus of her time, Mohd Rafi, she did not see eye to eye. Perhaps as the two leading voices in the industry there was a certain amount of friction, but the issue came to the fore because of a money dispute. Lata wanted singers to get half of the five per cent that the music director got from the producer. Rafi took the moral high ground that a playback singer’s claim on the film-maker ended with the payment of the agreed fee for the song. If the song flopped the singer had already been paid his fee for rendering it.

During the recording of the song Tasveer Teri Dil Mein from the film Maya, (1961), the two were not on speaking terms and Lata even lost her temper at him. Both refused to sing with the other. Later, at the insistence of S.D. Burman, although they decided to make up and sing together, but on a personal level they were not on cordial terms.

She won her first Filmfare best female playback award for Sahil Chowdhury’s composition Aaja Re Pardesi, from Madhumati (1958) and her second in 1962, for the song Kahin Deep Jale Kahin Dil from Bees Saal Baad, composed by Hemant Kumar. In 1969, she declined any further awards to give room to other artistes. In 2001, Lata Mangeshkar was awarded Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour, only the second vocalist to receive it. As Lata celebrates her 79th birthday today, her song rings even more true, encapsulating all that she is:

Naam bhool jaye ga; Chehra yeh badal jaye ga; Meri awaz hi pehchan hai….

1939: first musical show, at age 9

Ambarish Mishra, May 19, 2019: The Times of India

It was eighty summers ago that Lata Mangeshkar, then all of nine, presented her first musical show on a sultry evening in 1939. The GenNext of the Mangeshkar clan is rejoicing over the 80th anniversary of the diva’s Solapur concert, and a do at her Pedder Road residence is on cards. “It’s unbelievable how time flies. I think it happened only last month,” Mangeshkar told TOI over the telephone.

Having begun her riyaaz at age five under her father, legendary actor-singer Master Dinanath Mangeshkar, Lata was keen on performing on stage in keeping with the popular jalsa (public concert) tradition of yore. Opportunity came her way when her father, who presided over a repertory theatre company, pitched his tent in Solapur in 1939.

“Several music aficionados once came home with a proposal for jalsa. I overheard the conversation and promptly told Baba (father) that I too would share the honours with him. Baba laughed off my suggestion, You are too young for a public concert’,” reminisced Mangeshkar, the 2002 recipient of Bharat Ratna, for her sterling contribution to popular music.

The sponsors grabbed the idea with both hands though. They told Dinanathraoji that it would be a unique concert featuring two generations of the Mangeshkar family. Having finally got a nod from her father, Lata rushed to a nearby studio and finalised a photo shoot the following day. The Bhagwat Chitra Mandir auditorium was packed to capacity for what the sponsors had advertised as the ‘Pita-Putri (father-daughter) jalsa, a unique show’. Lata sang a composition in Raag Khambawati followed by a song from one of her father’s popular Marathi plays.

Having earned a prolonged applause from a select gathering of music buffs, and a couple of admiring glances from Master Dinanathrao, Lata subsequently sat next to her father.Soon, Master Dinanathrao began to deliver his trademark dazzling taans which reverberated through Bhagwat Chitra Mandir while Lata, her head rested on her father’s lap, went off to sleep. “I was a tad tired,” she said. Four years later, Lata sang for a Marathi film produced by Master Vinayak Karnataki following her father’s sudden death in 1942. In 1947, she joined Hindi cinema as playback singer and within a year the melody queen was belting out a string of hit songs. The rest, as they say, is history. “The Solapur jalsa very is close to my heart,” she says.

Lata Mangeshkar: In Her Own Voice

“Conversations with Nasreen Munni Kabir”

From the archives of “India Today”, May 1, 2009

Kaveree Bamzai

The problem with legends sometimes is that we take them too seriously. We give them high-faluting names, put them in pretty, neatly labelled boxes and keep them on the national mantelpiece, right up there with the Republic Day honours and titles like the Nightingale of India or the Voice of the Millennium. Which is what makes Lata Mangeshkar: In Her Own Voice worth its wrist-bruising weight. It shows the woman beneath the aura, the eternal singing star, the soundtrack to our lives for the past 60 years, playing the slot machines in Las Vegas allnighters, while sipping on Coca-Cola. The book speaks of an era where music and lyrics meant something more than a marketing tool. Where makeovers mattered less than mastery over the song. And where the established powers did not eat their young, hungrily. In the course of conversations over several months, Nasreen Munni Kabir draws out Mangeshkar on the subject of her music directors, her early difficulties, her supposed rivalry with her sister, even her disappointment, if any, for never marrying.

For the first time, we hear Mangeshkar’s voice, not in the haunting elegiac tone of Mahal’s emblematic Aayega aanewala or in the playful naughtiness of Lara lappa lara lappa from Ek Thi Ladki, but as the woman who became the fulcrum for her family when she was in her teens after her father, a well-known theatre producer and actor, passed away. She speaks of the early days when she acted in Marathi films, submitting to the humiliation of having her hairline cut back and her eyebrows trimmed. She talks of how she bought her first radio at 18 but returned it the next day when the first she heard on it that her idol K.L. Saigal had passed away. She tells Kabir of how she fell asleep in her father’s lap at her first public performance at the age of nine in Sangli.

The hard struggle is accepted as philosophically as the tremendous fame. And yet there is the undeniable sorrow at the passing of an era. Of an age where music directors would collaborate with each other. How Naushad would record part of a song for Roshan and Roshan would record another for C. Ramchandra. How her guru, Ustad Aman Ali Khan Bhendibazaarwale, would make her eat an omelette wrapped in a roti before she sang, because she was so thin. How after a long day of recording, she, Jaikishen, Shankar, Hasrat Jaipuri and Shailendra would eat ice cream or trot off to Chowpatty to eat bhel puri.

It was a simpler, gentler, kinder time. Fans would just walk into Famous Studios at Tardeo upon hearing she was recording there. She could simply refuse Jawaharlal Nehru when he asked her to sing the famous Aye mere watan ke logon again for him at his Teen Murti home. Or even when cross with Raj Kapoor for first announcing and then not choosing her brother as music director, she would go to RK Studios, without addressing anyone, sing the title track of Satyam Shivam Sundaram in one take and walk off. This is a woman, remember, who had no formal education. Who had the responsibility of taking care of a mother and four siblings. Who countered criticism with pure hard work—when Dilip Kumar once told her that Maharashtrians don’t speak good Urdu, she quickly hired a maulana to teach her the language.

And who spent her childhood, before her father went bankrupt, being a frightful bother to everyone, sitting inside a tyre so the girls could roll her down the street, climbing trees to pick guavas and mangoes and walking around the neighbourhood hitting everyone with a stick. A woman who was independent, feisty, and successful entirely on her own terms. A woman who never gave up or gave in. And through it all, kept her girlish gold payals on.

Personal life

Ambarish Mishra, February 7, 2022: The Times of India

There is a story about Lata Mangeshkar’s precocious understanding of music. Her father Master Dinanath Mangeshkar, who was teaching a student a particular composition, had to step out for an errand. He asked the youth to keep at it till he returned. Moments later, Lata, playing in the verandah, heard the teenage Chandrakant Gokhale. who later became a well-known actor, strike a false note. Unable to resist, she rushed in and began to sing the piece herself, exactly the way her father would. Dinanath, standing on the threshold, had tears in his eyes as he heard his daughter delineate the beauty of the ‘bandish’ in raag Puriya Dhanashri. A popular actor-singer, Dinanath was born in Mangeshi village of Goa in 1900. He joined a theatre group at 13 and honed his talent under Natyasangeet exponent Ramkrishnabuwa Vaze. He was 25 when he set up a repertory company, travelling through Dharwar, Belgaum, Sangli and Kolhapur where the wealthy patronised Marathi plays embellished with classical music. In her memoirs, Meena Khadikar, Lata’s sister, remembers him as an affectionate, yet stern father. “We were not allowed to use nail paint, facial cream or lipstick…Baba wanted us to live a simple life, pay attention to studies and adhere to family traditions and cultural practices,” says Khadikar. The children were occasionally allowed to watch films on spiritual traditions and values. Lata would often rope in siblings, cousins or maids to re-create scenes from Prabhat films like Sant Tukaram or New Theatres’ Devdas.

Dinanath was an admirer of K L Saigal; Lata was all of 11 when she sang ‘Main kya jaanoo kya jadoo hai’, a Saigal number, on Pune AIR. Meena recalls a concert in Solapur where Lata “insisted she wanted to share the stage with Baba who, after much persuasion, gave in. On the day of the concert she told Baba she would earn more rounds of applause than him, and she kept her word. ”

Though Dinanath’s plays were successful, lack of fiscal prudence led to problems. A failed attempt at film-making exacerbated the situation and he incurred debts which also sparked a court case. Master Dinanath’s health began to deteriorate. Lata was 13 when her father died.

Family, lineage

Raj Singh Dungarpur

February 7, 2022: The Times of India

Theirs was a love story wrapped in dignified silence. But Raj Singh Dungarpur, late president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, who had no ear for music, once admitted that he was “extremely close” to Lata Mangeshkar. It was believed the cricketer from a royal family in Rajasthan and the songster did not marry due to familial opposition. He had said: “We came from different backgrounds. The ‘60s was very different. Perhaps, both were very attached to their respective families. It was one of those things that just didn’t happen. But that has neither enhanced the relationship, nor has it reduced. She is the treasure house of my admiration and affection. ” It was a chance meeting between the demure nightingale and the strapping sportsman who lacked patience for concerts. In 1959, Dungarpur, a Ranji Trophy player, came to Bombay to pursue law, and Dilip Sardesai’s cousin Sopan took him to a house in Walkeshwar where Hridaynath Mangeshkar and his friends played cricket. The singer stayed in a two-bedroom flat close by. “I was invited to come up; I can’t remember if it was raining. She was utterly charming. She came to see me off and gave me her car…she invited my brother and me for dinner,” Dungarpur said in an interview in 2009.

Recalling the moment she won the Bharat Ratna, he said she could be “childlike”. “We were in London. She opened the flat and it was 11. 30 at night. The phone was ringing. She picked it up and said, ‘Wow!’ I said, ‘Hell! What wow is left for Lata Mangeshkar?’ She said, ‘Rachna (her favourite niece) is telling me I’ve got the Bharat Ratna. ’ The phones did not stop ringing that night. The next morning, you have to make a cup of tea yourself, I made one for her. She had her medicines and I asked her, ‘How does it feel to be a Bharat Ratna?’ She said, “Now that you ask me. . . bahut achha lagta hai’. ”

Her songs

Those rooted in classical music

SHRUTI JAUHARI SINGER/TEACHER, February 7, 2022: The Times of India

From: SHRUTI JAUHARI SINGER/TEACHER, February 7, 2022: The Times of India

The word for Sur was ‘Saam’ in ancient India. In present times it is known as Swar, a melodic and soothing sound. And if one wishes to listen and feel it (Swar) in all its perfection, Lata Mangeshkar’s voice is the personification of it. The legendary Ustaad Bade Ghulam Ali after listening to her said: “What we classical musicians take 3 1/2 hours to accomplish, Lata does in 3 minutes. ” She had beautifully reinvented her style from the classical to obtain the best results for light music. Much of it came naturally to her as she carried the genes of natya sangeet maestro, Pandit Dinanath Mangeshkar, especially the ability to render intricate Swar Sangati to perfection. This is evident in her very first song as playback singer ‘Naachu Yaa Gade, Khelu Saari Mani Haus Bhaari’ for a Marathi film Kiti Hasaal (1942). She was merely 13 years old then. The most mystifying feature in it was her perfect pitch rendition—a singer’s most precious vocal asset. This is something one is born with and extremely difficult to acquire. Her association with music directors Anil Biswas, Naushad, C Ramachandra, Sajjad Hussain in the 40’s and 50’s made for a rich body of work. Each one had his own preferences and she satisfied each of their highly specific requirements. If it was andolit swar demanded by Sajjad Hussain in ‘Aye Dilruba’ from the film Rustom Sohrab (1963), for Shankar Jaikishan it was a subtle touch in ‘Tera Jana’ for the film Anari (1959).

Pieces like ‘Pa Lagun Kar Jori’, the famous Pilu Thumri, revisited by Datta Davjekar for the film ‘Aap Ki Seva Mein’ (1946) stood out when she was still in her teens. In later years, she would render the same Raag Pilu with the tranquility of a lullaby in ‘Chandan Ka Palna’ for the film ‘Shabab’ (1954) and in ‘Na Manu Na Manu’ with breathtaking harkat to emphasise its chanchal aspects in Ganga Jamuna (1961) (both compositions were by Naushad). Anil Biswas’s Ek taal composition ‘Rooth ke tum to chal diye’ for ‘Jalati Nishani’ (1957) was similarly a masterpiece with pathos rendered through detailed note patterns.

When it comes to intricate singing, one has to but remember the genius of both music maestro C Ramachandra and Lataji, for compositions like ‘Radha na bole’ (Azaad,1955) in Rag Bageshri, ‘Balma Anadi’ (Bahurani, 1963) in Rag Hemant and ‘Dheere se aaja’ (Albela, 1951) in Rag Pilu. Not to forget the jugalbandi of the Meend-based Bihag composition ‘Tere sur aur mere geet’ (Goonj Uthi Shehnai, 1959) by Vasant Desai, in which she matched the flow of the shehnai played by none other than Ustad Bismillah Khan.

Madan Mohan specifically made tunes for her; among magical melodies created by the duo is ‘Pritam daras dikhao’ (Chacha Zindabad, 1959), a piece in Raag Lalit, accompanied by the great Manna Dey, is worth mentioning. The taans in this Teental composition are extraordinary. Any attempt to sing it seems futile.

‘Will Lata sing? Then I am safe,’ said S D Burman once. For only she could give voice to his thoughts on ‘Tum Na Jane’ (Sazaa, 1951), inspired by Rabindra Sangeet. When R D Burman scored the evergreen ‘Raina beeti jaaye’ (Amar Prem, 1972), moving in and out of Rag Todi, it could again only be handled by her. Every version of ‘Shyam na aye’ in this composition is a treat. Singing and singing effortlessly are entirely different. Singing effortlessly to perfection is yet another thing. This is what Lataji did to the classical style—she created her own three-minute masterpieces.

Malayalam

February 6, 2022: The Times of India

Lata Mangeshkar, the veteran singer, who infused emotions among the audience with her magical rendering of songs, is no more. The musical maestro’s contribution to the Indian music industry is immense, earning the title ‘Nightingale of India’. Lata Mangeshkar has recorded songs in over 36 Indian languages and a few other foreign languages. Although she has earned many fans from Kerala, it's a surprising fact that she has only sung one song in Malayalam, for the film ‘Nellu’ released in the year 1974.

The song ‘Kadali Chenkadali’ was sung by Lata Mangeshkar for the film ‘Nellu’ directed by Ramu Kariat. According to the sources, the songwriter Salil Chowdhury actually wanted to rope in Lata Mangeshkar for the Ramu Kariat directorial film ‘Chemmeen’ to sing the song ‘Kadalinakkare Ponore’. Due to some unknown reasons, Lata Mangeshkar turned back the offer and she later agreed to sing a song in the film ‘Nellu’ which was also directed by the renowned director Ramu Kariat.

The sources also suggest that it was the celestial singer KJ Yesudas who taught Lata Mangeshkar how to pronounce Malayalam to sing the song ‘Kadali Chenkadali’ in the film ‘Nellu’. Malayalis still remember the veteran singer Lata Mangeshkar for the beautiful rendering of the song ‘Kadali Chenkadali’. The lyrics were penned down by Vayalar Ramavarma and all the songs in the film ‘Nellu’ was composed by Salil Chowdhary.

The story of ‘Nellu’ was written by P. Valsala and the cinematography was helmed by Balu Mahendra. The film ‘Nellu’ had a battalion of talented casts that include Prem Nazir, Thrikkurissy Sukumaran Nair, Sankaradi, Kottarakkara Sreedharan Nair, and Adoor Bhasi.

Controversies

Tax troubles

Dhananjay Mahapatra, February 7, 2022: The Times of India

New Delhi: On January 26, 1963, even as Lata Mangeshkar reduced then PM Jawaharlal Nehru to tears with her rendition of ‘Ae mere vatan ke logon’ — in the aftermath of 1962 Indo-China war that had wounded the national pride and psyche — the income-tax department was preparing to swoop down on her. The annals of Bombay high court bear testimony to Lata’s tryst with the I-T department, which began right after the country gained independence in 1947. Fortunately, she had the invaluable assistance of legal eagle Nani Palkhivala to ensure that the tax department was stopped in its tracks at the level of the constitutional court. HC records also show how the court’s respect grew for the melody queen, in keeping with her rising stature, over the years. The references to her in

the judgments changed from “a singer by profession” in 1958 to “a well-known playback singer” to an “acknowledged playback singer” in the 1970s.

Just days after the Republic Day function at New Delhi’s National Stadium, the I-T department questioned Lata’s returns for assessment years 1962-63, 1963-64 and 1964-65, focusing on receipts of Rs 1,43,650, Rs 1,38,251, and Rs 1,19,850, respectively, which were principally based on diary entries maintained by her in respect of receipts from professional work as a playback singer. An I-T officer had come across a ledger maintained by Vasu Films in Madras (now Chennai) containing certain entries and, based on them, taken the view that Lata had concealed her real income.

After going through the arguments on behalf of the I-T department and Lata, the HC on June 20, 1973, said, “Since we are upholding the tribunal’s view on the additions, no question of levying penalty can arise. ”

In another proceeding, the I-T department had questioned how she organised the money to purchase a flat in ‘Prabhu Kunj’ at Peddar Road for Rs 45,000 on August 23, 1960. Lata had another flat at Walkeshwar, which was sold on October 12, 1960.

Her run-ins with the I-T department continued till early 1990s, as is evident from a Bombay HC judgment dated December 30, 1991. The I-T department had appealed against a decision by the commissioner of income tax (appellate) allowing relief to Lata to the tune of Rs 3,91,570 earned from concerts in foreign countries.

The HC dismissed the I-T department appeal and said, “We agree with the CIT(A) that there was no justification for treating any portion of the expenditure incurring in India as relatable to the receipts abroad. . . ”

Politics

Pays tribute to Savarkar

Ambarish Mishra, May 29, 2019: The Times of India

Lata chides Savarkar’s detractors

Mumbai:

Lata Mangeshkar paid glowing tributes to Veer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar to commemorate his 136th birth anniversary. The melody queen and her family have been staunch followers of Savarkar.

In a series of tweets, Lata described Savarkar as a “deshbhakt” (patriot) and a “swabhimani” (a proud soul). “Aaj Swantrya Veer Savarkar-ji ki jayanti hai. Main unke vyaktitva ko, unki desh bhakti ko pranam karti hoon (Today is Swatantrya Veer Savarkar’s birth anniversary. I pay my respects to his personality and his patriotism),” she tweeted.

Chiding the freedom fighter’s detractors, Lata said, “These days, some people speak against Veer Savarkar, but they don’t know how towering a patriot and a proud soul he was.” In another tweet, Lata posted a link of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s famous 1988 speech on Savarkar. Paying tributes to Savarkar, Vajpayee had recalled the latter’s committment to India and his sacrifices for the cause of freedom.

Lata also recalled Savarkar’s songs which she sang along with her brother, Pandit Hridayanath, and sisters Meena, Asha and Usha. Her ties with Savarkar date back to the 1930s when Master Dinanath, Lata’s father and an accomplished singer-actor who owned a theatre company, performed Savarkar’s plays across Maharashtra.

Bhajan for Advani

BJP member LK Advani recalled that Lata recorded a bhajan for his rath yatra in 1990 “Ram naam mein jaadu aisa, Ram naam man bhaaye, man ki Ayodhya tab tak sooni, jab tak Ram na aaye. ” He said it became the signature tune of the yatra.

Vignettes

Her biographer, Yatindra Mishra, reminisces…

The award-winning biographer of Lata Mangeshkar looks back at the life and times of the singing sensation, from the time she entered the music industry to how she trained herself to sing and dominated the music industry for over six decades

When Lata ji came to the film industry, actors such as KL Saigal, Suraiya or Kanan Devi were singing [their own songs]. It’s only with her, Mukesh and Mohammed Rafi that playback singing actually started. 1949 was one of the most significant years of Lata ji’s career.

At 15, she blew the nation’s mind with “Aayega Aanewala” ( Mahal, music director Khemchand Prakash), and followed it up with megahits from the films Barsaat (Shankar-Jaikishan), Laadli (Anil Biswas), Andaz (Naushad), Bari Behen (H Bhagatram) and Bazaar (Shyam Sunder). Remember, this was the time when artists like Zohrabai Ambalewali, Amirbai Karnataki, Rajkumari and Shamshad Begum were at their peak. It was no mean feat to challenge them with such a distinctively new style. This was also when Saigal, a huge star of the time, had passed away and Noor Jehan had left for Pakistan, leaving a huge musical void. Lata ji and Mukesh filled it up — they also became a huge success as a pair with the duet “Ab Darne Ki Koi Baat Nahi” ( Majboor, 1948).

The decade that followed is without doubt musically her best. There were films like Baiju Bawra (1952), Anarkali (1953), Nagin (1954), Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje (1955), Shri 420 (1955), Chori Chori (1956), Mother India (1957), Madhumati (1958), Parakh (1960) and Mughal-E-Azam (1960). All were great musical hits

Lata ji brought respectability to film music, and imbibed the ‘sugam sangeet’ or light music genre with her classical training to

create a whole new gold standard. She introduced a refinement and nuances that was hitherto nonexistent in Hindi film music.

Take for instance, how she changed how certain words are pronounced. Earlier, people used to say ‘mahabbat’ (love); she replaced it with “mohabbat” in Anarkali’s hit number “Mohabbat Aisi Dhadkan Hai”. She knew how to regulate her breathing and so, her music never sounds harsh or nasal. She showed how to create a whole raagdari in all of the three minutes of a movie song with all the phonetic and grammatical training of classical music.

If you want to listen to a Shudh Kalyan and Bhopali combination, there’s “Rasik Balma ( Chori Chori); for Bhimpalasi Raag, tune into “Naino Mein Badra” ( Mera Saaya, 1966); for Mishra Khamaj, go to “Thare Rahiyo” ( Pakeezah, 1972).

It’s also important to note that Lata ji worked over six decades and each decade was dominated by music directors with greatly different styles. There were Shankar-Jaikishan, Naushad and Anil Biswas in the early 50s, followed by Salil Chowdhury, SD Burman, Chitragupt and Madan Mohan, and then Kalyan-Anand and Ravi in the 1960s. RD Burman and Laksmikant-Pyarelal dominated the 70s and 80s, and Lata ji went on to sing some memorable numbers for Bappi Lahiri and later AR Rahman as well.

After Biswas directed her for “Beimaan Tore Nainwa” in the Dilip Kumar-Madhubala-starrer Tarana (1951), he had said, “Finally we have a singer with whom we can experiment with music.” Jaidev ji made her sing to “Prabhu Tero Naam” ( Hum Dono, 1961) and when she complained that the pitch was making her voice crack, he replied, “If Lata Mangeshkar’s voice cracks, then who can sing this song? I can’t think of anyone else.” For Junglee’s (1961) “Ehsan Tera Hoga Mujh Par”, Lata ji had to match her pitch with Mohammad Rafi’s, whose rendition had already been filmed – a very difficult task because male and female pitches are very different.

Lata didi never stopped learning. Dinanath Mangeshkar, her father, was trained in the Gwalior gharana. After his demise, she trained under Ustad Aman Ali Khan Bhendi Bazar Wale, Ustad Amanat Khan Dewaswale and Tulsidas Sharma. She learnt how to enunciate from Master Ghulam Haider, and how to breathe from Anil Biswas. Naushad taught her how to amalgamate folk music with the raagas, Madan Mohan and Roshan trained her further in classical music and ghazals. She is the textbook of playback singing. To master diction in Sanskrit, Marathi, English and Urdu, she studied with Goni Dandekar, Babasaheb Purandare, Ram Gabade, Maulvi Mehboob and musician Mohammed Shafi — all the while working in five to six shifts and churning out one hit after another.

She was also a pathbreaker who fought for the rights of musicians. When she began her career, the film industry was completely male-centric and revolved around banners such as Bombay Talkies, New theatres, RK Films and Bimal Roy Productions — all dominated by men. But Lata ji’s commercial success was unmatched.

Leading ladies Meena Kumari, Nargis, Madhubala and Nutan had it inked in their contracts that their songs would be sung only by her. The producers couldn’t ignore her or what she fought for.

The first rebellion was when she and poet-lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi protested against All India Radio’s practice of displaying the names of the fictional characters played by actors on the labels of LP records. So, the label for “Aayega Aanewala” said ‘sung by Kamini’ (the character played by Madhubala in the film).

After the number’s huge popularity, people too had begun to ask who the playback singer was. Eventually, this led to the printing of names of singers and lyricists on the records in around 1950. The next was the demand for royalties for singers during the release of Sangam (1964). It’s because of her that today all singers, irrespective of genre or seniority, get royalties for their work. She was not fighting only for herself.

It’s also thanks to her that Filmfare Awards introduced the categories for best playback singers and lyricist in 1958 — Lata ji won the first award for playback for “Aaja Re Pardesi Main” ( Madhumati, 1958) and Shailendra as the best lyricist for “Yeh Mera Deewanapan Hai” ( Yahudi, 1958).

She was an excellent cook and loved reading and watching comedies and thrillers — Padosan and Crime Patrol were big favourites. She loved attending concerts by Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Amir Khan. She used to say that it was Ustad Amir Khan’s music that helped her sail through phases of depression.

‘I don’t want to be born again’

Lata lived a long life of epic proportions. The sheer number of songs she sang is staggering; she became a legend in her lifetime. Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan famously said of her: “ Kambakht kabhi besuree nahin hoti (the wretch never misses a note

I find solace in the Marathi saying that she used to quote while discussing her mortality: ‘Gaon gela vahun, naon gela rahun’ (the village is swept away by the flood, but its name remains in memory). She will surely live on in our collective memory. The Naushad-Shakeel Badayuni song of lament in Mughal-E-Azam, “Khuda Nigehbaan Ho Tumhara Dhadakte Dil Ka Payam Le Lo / Tumhari Duniya Se Ja Rahe Hain, Utho Hamara Salam Le Lo...” has acquired a rare poignancy today.

As told to Suktara Ghosh

Yatindra Mishra is a musicologist and is the authentic biographer of Lata Mangeshkar.

Banarasi saris

As she was very fond of Banarasi saris and used to wear sarees made by the sari makers of Varanasi named Armaan and Rizwan. She came to varanasi only once in her lifetime and made a special relationship with Armaan Ahmed who sent saris to her. .

A 13-year frost with Dilip Kumar

Both Lata Mangeshkar and Dilip Kumar have left an indelible mark on Indian cinema. They shared a beautiful bond and when Dilip Kumar bid adieu to the world, Lata Mangeshkar wrote a moving tribute in the memory of her ‘older brother’. However, there was a time when the two didn’t speak to each other for a period of 13 long years.

According to reports, when Dilip Kumar told music composer Anil Biswas that ‘the Urdu of Marathis is like dal and rice”, as Lata Mangeshkar had been chosen to sing ‘Laagi Naahin Chhute’ for his film, ‘Musafir’, in 1957, she was quite offended and decided to hone her Urdu skills. It was 13 years down the line when they met and celebrated Raksha Bandhan.

When they met in 1970, Lata ji remarked, ‘You know, Yusufsaab, I'd always heard you loathed me for being one up on you while recording the Laagi Naahin Chhute Rama duet with you in Musafir. But I only sang the way I can't help singing any number.’ Dilip Kumar then responded, 'It's precisely because you can't help singing the way you do that my family and I adore you! How possibly could I loathe a voice so heavenly!’

Frostier with Rafi

legendary singer Lata Mangeshkar laughed at Mohammed Rafi during a live show.

Her last recorded song

Do you know which song Lata Mangeshkar last recorded? It was for the wedding of Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani and Anand Piramal in 2018 that Lata didi recorded her last song. She sang the Gayatri Mantra along with a message of ‘congratulations’ for both the families. The couple got married on December 12, 2018 and the legendary singer’s recording was played during the wedding. And according to past reports, Mangeshkar had recited the Gayatri Mantra perfectly in a single take.

The most recorded artiste in history

She was honoured with Dadasaheb Phalke Award and France's highest civilian award, Officer of the Legion of Honour, besides numerous national and international awards. In 1974, the Guinness Book of Records ranked her as the most recorded artiste in history. She had reportedly sung over 25,000 songs between 1948 and 1974. She became a recipient of India's highest civilian honour Bharat Ratna in 2001.