Mahatma Gandhi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

The British

Vis-à-vis Churchill

Suneel Sinha , Oct 1, 2019: The Times of India

Two men who would find themselves implacably opposed to each other for close to half a century would have first glimpsed each other in the aftermath of a battle.

Gandhi and Churchill would have been yards apart on Spion Kop (Spy Hill) in Natal, South Africa, on January 24, 1900, a book suggests, even if neither then knew the other or that the outcome of future decades would lead to the elevation of one to the Mahatma who would dissolve the empire the other lived and breathed.

Gandhi of the Indian Ambulance Corps was carrying a wounded general, Edward Woodgate, on a stretcher that passed by Churchill, then a young reporter during the Second Boer War who had been commissioned as a lieutenant in the South African Light Horse. “In fact, he and Gandhi must have passed literally within yards of each other…” the historian Arthur Herman writes in “Gandhi and Churchill”. The yet-to-be British statesman would acknowledge this years later.

They would meet in person just once — when Gandhi called on Churchill who was then colonial undersecretary in the first decade of the 20th century — and well before Churchill would train epithet and invective at his immovable opponent.

While Gandhi received his real education reading law at University College London, where he was also drawn by the Theosophists, to studying the Bhagavad Gita, second lieutenant Churchill would begin in Bangalore the voracious reading that would later lead to a Nobel Prize in Literature.

The adversarial lives of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Winston Spencer-Churchill began in irony. For Churchill, it ended in one. He was buried in 1965 on the date his adversary was assassinated in 1948.

Books about Gandhi

As in 2019

Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

1 The Life of Mahatma Gandhi- Loius Fischer

2 Gandhi and his critics- BR Nanda

3 The Good Boatman- Rajmohan Gandhi

4 Prisoner of Hope- Judith M Brown

5 Gandhi: A very short introduction- Bhikhu Parekh

6 The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the temptation of violence- Faisal Devji

The Dandi March

The route

Parth Shastri , Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

With inputs from Radha Sharma

It’s been 89 years since Mohandas K Gandhi electrified the world by walking 388 km from Ahmedabad’s Satyagraha Ashram to a town called Dandi on the Arabian Sea to defy a British tax on salt. The image of the 61-yearold with lathi in hand and 78 followers in tow has inspired many others — from politicians and students to activists and foreign tourists — to reprise the 1930 yatra. TOI traces the route where history was made…

1 Sabarmati Ashram

Mahatma Gandhi shifted his ashram from Kochrab to the banks of the Sabarmati on June 17, 1917, because he wanted to take his experiments in simple living a step further. Also, the site was between the Sabarmati jail and a crematorium — the two places where satyagrahis end up, Bapu believed. This became Bapu’s home till 1930. At the ashram, he continued with his experiments with truth, and also brought together a group of men and women who believed in non-violence as the means to set India free. Today, the ashram, which draws anywhere between 500 to 3,000 visitors daily, stands as a monument to Bapu’s life mission. According to Gandhi scholar and former director of Sabarmati Ashram Tridip Suhrud, the Dandi march was a “collective demonstration of the ideals of the Satyagraha Ashram.”

2 Nadiad

The marchers spent the fourth night at Santram Mandir. Ashish Dave, a local historian, said the mahant (chief priest) of the temple, Jankidas Maharaj, stepped out to receive the Mahatma. “The social more at the time was that once appointed, the mahant could not leave the temple premises,” Dave said. “It was the first instance of the protocol being broken.” Nadiad has a memorial dedicated to the Mahatma and Sardar Patel commissioned by former union minister Dinsha Patel, whose relatives were among those arrested in aftermath of the march.

3 Borsad

The epicentre of the Borsad Satyagraha (1922-23) — launched by Sardar Patel to abolish tax on villagers to fight against dacoits — was the site of the sixth night’s stay. The town has preserved the Mahatma’s memory in the form of a century-old high school whose first trustee was Sardar Patel. Ilesh Sharma, principal of JD Patel High School, said, “The balcony from where the Mahatma addressed the gathering still exists in its original form.” However, the structure, despite being declared as heritage, has been damaged by recent spells of rain.

4 Kankapura

The village of 1,200 people on the banks of the Mahi was the spot for the seventh night’s halt. It is believed that the boatmen who ferried the satyagrahis were afraid that their vessels would be seized by the British. Today, the main problem for the villagers is connectivity across the river for better employment opportunities. Former sarpanch Vinu Parmar, 75, says he has written several letters to authorities, including the PM’s office. “The Mahatma had to cover 7km between the banks. By road, the distance is 35km,” he said.

5 Kareli

The resting spot for the eighth day is where Jawaharlal Nehru met the Mahatma to seek guidance ahead of a Congress meeting. A Dandi Path hostel has been built by Gujarat Tourism at the location and the rooms used by the leaders have been preserved. Hemant Mahant, manager of the hostel, says that that about 100-odd persons from India and abroad have come tracing the Mahatma’s path in the past one year. “Earlier this year, a Swiss couple came here while tracing the same route on a bicycle. A German national walking the Mahatma’s path was so particular about adhering to the routine that he would start walking from the exact place where he suspended his journey for a night stay,” he said.

Another historic spot is the residence of Nathubhai Bhatt, where the marchers stayed on the 17th day. This is among the few private residences with Dandi March history. Nathubhai’s son Harish Bhatt, said: “Our family was touched by the Mahatma’s magic. We continue leading a simple life and not wasting any resource.”

6 Bhatgam

This was the spot where Gandhi made a moving speech about a labourer who was forced to carry a kerosene burner on his head during the march. “No worker should be made to carry such a load on his head. If we do not mend our ways, there is no Swaraj such as you and I can put before the people,” he said. He and the group stayed in school which has been named Gandhi Kutir, a structure that is fast eroding according to Ishwar Patel, a village elder.

7 Dandi

On April 5, the 23th day of the march, the Mahatma stayed at Saifee Villa, owned by religious leader from the Dawoodi Bohra community. The Syedna later handed it over to Nehru so that it could be preserved as a museum. At dawn, the Mahatma picked up salt from the shore, defying a British law over manufacture of salt. The memorial here gets over 15,000 visitors every month. It has 24 free-standing pillars depicting an event from each day of the march. An 18-foot statue of the Mahatma is flanked by two spires which converge at a crystalline point made of salt. The main attractions, however, are the lifelike statues of the Mahatma and 78 marchers.

Shantanu Iyer, who had come from Mumbai on a rainy day to visit the memorial, said that she had only read about the event in history textbooks. “But looking at the spot and going through the entire history is like re-living those days and understanding its importance. I hope our future generations remember what our forefathers did to give us freedom,” she said.

Delhi

Taught English, Hindi while at Valmiki temple, Reading Road

Sep 30, 2019: The Times of India

When Gandhi taught at a Harijan basti in Delhi

The black board, used by none other than Mahatma Gandhi during his classes to teach his students, is still intact. While the world knows Gandhi as an apostle of peace, a leader of the freedom struggle and a social reformer, not many are aware that he briefly became a regular teacher to a bunch of kids and their parents in Delhi. He taught English and Hindi when he started living at Valmiki temple on what was then Reading Road (now Mandir Marg). That was perhaps the first and only time when he became a teacher in the true sense.

When you visit Bapu’s room inside the Valmiki temple, you will see several old photographs of leaders like Lord and Lady Mountbatten, C Rajagopalachari, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Maulana Azad and Jawaharlal Nehru with him. However, one painting tells you the story of this venerable room. In this fading painting, several kids are talking to Bapu in a very animated manner.

In the centre of Bapu’s room, you will find a wooden desk that he used. To the right is the bed that Gandhi slept in. Bapu’s small charkha is also there, close to the bed. He used to spin it for around 30-40 minutes every day. Everything is there in the same position that Gandhi left more than seven decades ago. Gandhi chose this place so that he could live with ‘Harijans’. In those days, a large number of Valmiki families lived in slums at the Valmiki colony close to the temple. They worked as sweepers in areas like Gole Market, Irwin Road (now Baba Kharak Singh Marg) and Connaught Place. Many Valmiki familes still live there now, though in decent flats. The jhuggies are long gone.

In 1946, Gandhi asked elders of the Valmiki colony if could stay there for a couple of months. They gladly agreed. Gandhi stayed there from April 1, 1946, to June 10, 1947 — for 214 days, to be precise.

“Once he moved to Valmiki colony, he started interacting with the families. He was shocked to learn that they were all illiterate. Nobody had even seen a school. Then he asked them to send their kids to him as he would teach them. People started sending their kids to his classes,” says Krishan Vidhyarti, a priest and caretaker of the temple. Vidhyarti’s father and uncles also attended Bapu’s classes. Gandhi wanted to teach them to read and write basic English and Hindi. And he ensured that his classes took place both in the morning and evening, without fail.

Gandhi was a hard task master. He would chide students if they turned up in his class without taking a bath. He was also a conscientious teacher. He would put off meeting leaders who came visiting to get on with his classes. Louis Fischer writes in his biography of Gandhi, “The Life of Mahatma”, “Once I reached at the Valmiki temple from my Hotel Imperial to interview him. But, he met me only after the prayers.” Fischer spent over a month in Delhi in 1946 to collect notes for his biography.

“I grew up listening to stories of Gandhiji teaching at the Valmiki temple from my father. He had attended Ganghiji’s classes during those days,” says Pritam Dhaliwali, 64, a social worker of Gole Market area. “Thanks to Bapu, my father became a little literate.”

When Bapu began teaching, kids of Gole market, Paharganj, Irwin Road and other nearby areas too started attending. The number of students kept swelling. From about 30 students when Bapu started, it soon grew to about 75. Classes then had to be held in an open area. It is said Gandhi knew all the students by their names.

“It was Bapu who taught our elders. They were illiterate and came to Delhi from Meerut and other parts of western UP. But for him they would have remained as they were. After Bapu left Valmiki temple, his students joined various schools in the Gole Market area,” says Dr OP Shukla, a Dalit activist and former member of the Railway Board.

“It was a big blow for us when he was forced to shift from here to Birla House for security reasons. Our elders were devastated. Alas, he was killed where security was tight,” Vidhyarti, the temple priest, says.

Vivek Shukla is the author of ‘Gandhi’s Delhi’

Events in his life

1915: Kochrab Ashram, where Gandhi became a Mahatma

Leena Misra , Ritu Sharma, March 17, 2024: The Indian Express

“In a bid to end the chatter, the guest, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi told them one day, ‘I am not idle. I am thinking about how to start a war against the British’,” says Desai’s grandson Shailesh Diwan, 86, narrating an account that has passed down in the family since 1915.

According to Diwan, Desai and Gandhi had studied law together in London. On his return from South Africa, Gandhi stayed at Desai’s bungalow in the now-crowded Kalupur area which is near the railway station.

A ‘vacation home’ that became Bapu’s first ashram in India

Desai later let out his “vacation home”, a European-style bungalow with a large garden, in Kochrab village, then on the outskirts of Ahmedabad on the banks of the Sabarmati river, to Gandhi. It was here that the Mahatma would start his first ashram, the Satyagraha Ashram, in India, on May 25, 1915, and begin his experiments with truth.

Gandhi started his first ashram, the Satyagraha Ashram, at Kochrab on May 25, 1915. He shifted it to Sabarmati in 1917, following the outbreak of plague. Nirmal Harindran Diwan and his wife Gita visited the bungalow standing in a 5000-sq metre plot, on March 13 this year, to relive old memories. A day earlier, PM Narendra Modi had inaugurated the renovated Kochrab ashram virtually, while laying the foundation of the Gandhi Ashram Memorial and Precinct Development Project in Ahmedabad’s Gandhi ashram.

“Since both did not believe in freebies, my grandfather and Gandhi decided on annual rent — Re 1 — for the Kochrab house,” says Diwan, who has recently moved to Ahmedabad from Mumbai.

A plaque on the bungalow’s wall says Morarji Desai, then the Chief Minister of Bombay who would later become the Prime Minister, declared the “historic and pure” ashram in Kochrab a memorial on October 4, 1953, five years after Gandhi’s assassination. In 1954, while Morarji Desai was the Chancellor of Gujarat Vidyapith, the varsity founded by Gandhi in Ahmedabad, the ashram’s management was handed over to the Vidyapith, though its ownership remained with the state.

The two-storey building’s thick walls plastered with limestone and the wooden ceiling resting on varnished logs offer much-needed respite from the blazing Ahmedabad sun. During a tour, Bhim Bahadur, 44, the caretaker of 22 years, unlocks the aged but strong iron latches on each of the solid wood doors to the rooms and flips the antique black switches, each of them working.

The ground floor, surrounded by a verandah, has rooms used by Gandhi, Kasturba, the other inmates and for storage. A wooden staircase leads to the top floor, which has a low-seating conference room and a library with wooden flooring. While the ground floor has bathrooms, the first floor has a spacious balcony. Bahadur says everything in the house is over 100 years old, including the wooden blinds on doors. A heavy brass bell hangs from the ornate eaves of the upstairs balcony. “This was rung to ensure everyone was up at 4 am, came down for prayers by 5.30 am, had meals on time and went to bed by 9 pm,” says Bahadur, who belongs to Nepal.

A separate single-storey building on the rear side is a kitchen, with a roof made of “imported tiles”. It also has a storeroom, toilets and bathrooms. “The small room used as a store has a large cupboard, so big that it cannot pass through the door which suggests it was built inside this room and dates back to Gandhiji’s time,” says a booklet on the ashram by Ramesh Trivedi, a retired Vidyapith teacher who looked after the ashram for over 18 years, before relocating to Canada.

Another longish building, Paanch Ordiyo (five rooms), on the premises was used for activities like weaving and carpentry. The newest addition at the Kochrab premise is an Activities Centre, built in modern design, with around 10 rooms on the top floor, including four air-conditioned ones that are named after various ashram inmates, including Dudhabhai Dafda, a Dalit weaver whose family Gandhi took into the ashram causing outrage among some inmates.

While the Diwan family is not too happy with the contrast this building poses against the original buildings, they are happy it has been restored and renovated, in an “as was” condition.

The earthquake on January 26, 2001, caused immense damage to the building. Trivedi was posted at the ashram around that time by the then Vidyapith Vice-Chancellor. He took charge of the repairs with government funds, including replacing the broken Kota stone floor in Gandhi’s room with a mirror-polished version.

“We are happy that nothing has changed in the building after the latest renovation. Otherwise, what is the point?” says Diwan.

When Gandhi would stopped by for a chat

Historian Rizwan Kadri, who lives in his ancestral home at Kagdiwad, a stone’s throw from the ashram, is among those who pushed the authorities for the upkeep of the ashram. He says his grandfather Nooruddin Kadri came to Kochrab, which lies on the west bank of the Sabarmati, in 1910 from Raikhad, on the east bank, “to get away from the crowd”. The family came to be known as the ‘Bootwala family’ since they owned the Gujarat Boothouse.

Kadri says, “On the way to the Sabarmati river, Gandhi would often stop by at our house to chat with my grandfather.”

Mahatma-ni Parikrama (The path of the Mahatma), a book Kadri wrote, inspired by notes from Gandhi’s diary that are preserved at the National Gandhi Museum in Delhi, has details of how Gandhi and Kasturba did a vastu puja at the Kochrab Ashram on May 20, 1915, before moving in. On the ashram’s centenary, Kadri had organised an event, along with the Swaminarayan Gadi Sansthan, Maninagar, to release his book on Gandhi and Lokmanya Tilak.

Over the years, however, the Kochrab ashram became a victim of neglect. “Luxury buses would remain parked outside, creating a mess, even as the ashram would remain mostly closed,” says Kadri.

At least 15-30 feet of the ashram’s front space was taken for the expansion of Ashram Road, an arterial road in Ahmedabad, in lieu of compensatory land on the rear side.

Showing pictures of the decorated ashram on March 12, 2024, which also marked the 94th anniversary of the Dandi March, after PM Modi inaugurated it virtually, Bahadur told The Indian Express, “Iss mitti ko aap sar par rakkho. Jo kaam tay kiya hai, woh zaroor hoga. Utna power hai iss jagah ka (pick up the earth here and place it on your head. Whatever task you have set out to achieve, will be successful. Such is the power of this place).”

“Earlier he (PM) was to come here, but he inaugurated it digitally. Maybe because the ashram is in a crowded part of the city and would have inconvenienced people,” he rues.

A series of wall panels quoting from his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, tell the story of the ashram under Gandhi. A panel states how many friends convinced Gandhi to choose Ahmedabad over Haridwar and Rajkot where he did his schooling.

Kadri’s book says it was Ahmedabad-based Dr Hariprasad Desai among those who convinced Gandhi to choose the city during the Mahatma’s first visit to Ahmedabad in January 1915.

“I had a predilection for Ahmedabad. Being a Gujarati, I thought I should be able to render greatest service to the country through the Gujarati language. And then, as Ahmedabad was an ancient centre of handloom weaving, it was likely to be the most favourable field for the revival of the cottage industry of hand spinning. There was also the hope that the city being the capital of Gujarat monetary help from its wealthy citizens would be more available here than elsewhere,” Gandhi writes in his autobiography.

The panels also clarify why he chose the name Satyagraha Ashram instead of ‘Sevashram’ or ‘Tapovan’, as suggested by others. His autobiography explains, “…I wanted to acquaint India with the method I had tried in South Africa, and I desired to test in India the extent to which its application might be possible so the name Satyagraha Ashram to convey goal and method of service”.

According to Kadri’s book, when Gandhi decided to settle in Ahmedabad, “he transformed the ashram into an antithesis of everything Ahmedabad stood for in those days. Here was a city of moneyed mill owners who lived a life of opulence. In stark contrast, the Satyagraha Ashram at Kochrab was defined by austerity”.

The ashram started with 25 men and women, 13 of them Tamilians, who had accompanied Gandhi back from South Africa. The ashram took in children as young as four years old, with their parents’ consent. The strength grew to about 100 inmates, including Vinoba Bhave and Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar, an activist from the freedom movement, in the two years that Gandhi occupied it.

A Dalit family comes to the ashram

On September 11, 1915, in a hit on untouchability — which he considered a “blot” on the country — Gandhi took Dudhabhai, a Dalit weaver and his family, into the ashram. Initially, there were vehement protests by the inmates, including Kasturba.

“This upset a neighbouring community and even Vaishnav businessmen refused to fund Gandhiji’s activities. Bapu (Gandhiji) told the ashram inmates that if a boycott was declared and they were left without funds, they would shift to the untouchable’s colony. One morning, a wealthy businessman from Ahmedabad anonymously donated Rs 13,000 to the ashram,” writes Kadri, adding that many believe the benefactor was textile baron Ambalal Sarabhai.

Kadri co-relates dates from Gandhi’s diary, where a note on September 17, 1915, states that “Ambalal Sheth came today”. Gandhi also started an ‘Antyaj Ratri Shala’ for Dalits at the ashram, besides encouraging the inmates to practise celibacy, do physical labour and wear swadeshi.

In June 1917, when plague hit the city, Gandhi shifted the ashram to Sabarmati, some 8 km away. In Sabarmati, he founded the Harijan Ashram, now popular as the Gandhi ashram.

Although Diwan does not have any historic documents on the exchange between his grandfather and Gandhi, the extended Desai family, spread between Ahmedabad and the US, often gets together at Kochrab for family photographs.

They are also happy to have the permission to “host some family events there some times, while maintaining the sanctity of the place, without band-baja,” says Gita Diwan.

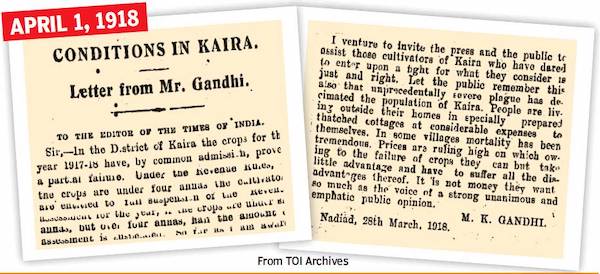

1918: Kheda

August 29, 2021: The Times of India

From: August 29, 2021: The Times of India

In March 1918, Mahatma Gandhi organised the Kheda satyagraha, one of his first, in Gujarat when the government raised taxes by 23% at a time when the region was struck by famine, cholera and plague. Gandhi led peaceful protests and convinced peasants not to pay the tax, which was met with a heavy-handed British response to seize land and property. But the movement ultimately yielded results — the tax was scrapped and all confiscated property returned. In this letter to the editor published in the Times of India, Gandhi argues against the tax on behalf of Kheda’s farmers.

1921: dress worn

From: August 29, 2021: The Times of India

See picture:

Mahatma Gandhi pictured with Lord Mountbatten in Delhi in 1947. In 1921, Gandhi had shed his suits and ties from his days as a lawyer, and began wearing a dhoti. He made the choice in Madurai when he saw “ill-clad masses” and decided a simpler, more traditional attire would allow him to better represent India’s rural poor

1922: sentenced to six years in prison

May 15, 2022: The Times of India

Gandhi sentenced to six years in prison

The great trial

On March 18, a frail man in his trademark loincloth appeared at the Old Circuit House in Ahmedabad’s Shahibaug without a counsel. According to the TOI report, a “large number of ladies and gentlemen were admitted by ticket” for the trial that lasted about an hour and a half. The report states that at the outset the charge under Section 124A in connection with three pieces — "Tampering with Loyalty", "A Puzzle In Its Solution" and "Shaking the Manes", written by Gandhi and published in Young India , which he used to edit — were read out. Bapu and Shankarlal Ghelabhai Banker, the publisher, were charged with “bringing or attempting to excite disaffection towards His Majesty's Government established by law in British India, and thereby committing offences punishable under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code”. With characteristic sincerity, Gandhi pleaded guilty in front of sessions judge RS Broomfield to all the charges against him, including sedition. Also in court were Thomas Strangman, the advocate-general, along with Girdharlal Uttamram, public prosecutor of Ahmedabad, appearing for the Crown.

The action against Gandhi was deemed as the British government’s response to his open challenge to them in one of his articles: “We seek arrest because the so-called freedom is slavery. We are challenging the might of this [British] government because we consider its activity to be wholly evil. We want to overthrow the government…”

Crime and punishment

According to this report, which draws heavily from Justice Shelat’s book Trial of Gandhiji and Thomas Strangman’s Indian Courts and Characters after both Gandhi and Banker pleaded guilty, the judge wanted to “immediately pronounce the judgement”, but was stopped by Strangman.

The AG, according to the TOI report, stressed that Gandhi was a “man of high educational qualifications” and the “court had to consider what result a campaign of the nature disclosed in the articles was likely to lead to if unchecked” and referred to the events that took place in Bombay, Malabar and Chauri Chaura, leading to “riots and murders”. He then turned to Gandhi and asked, “Of what value is it to insist on non-violence, if incessantly you preach disaffection towards the government and hold it up as a treacherous government, and if you openly and deliberately seek to instigate others to overthrow it?" When Justice Broomfield asked Gandhi for a response, he replied by saying that he had prepared a lengthy statement, but also wanted to add a few words. “I had either to submit to a system, which I considered had done irreparable harm to my country, or incur the risk of the mad fury of my people bursting forth, when they understood the truth from my lips," Gandhi said in court, while admitting that the AG had been extremely fair. “I know that my people have sometimes gone mad. I am deeply sorry for it.”

He then asked the judge to either resign or inflict him with the highest penalty, if he believed the system of law enforced by him was good for the people of India. “By the time he had finished speaking, the court would perhaps have a glimpse of what was raging in his breast and why it was that he had run the risk which a sane man would not have done,” states the TOI report.

TOI report on Mahatma Gandhi's sentencing on sedition case in 1922 In his statement, Gandhi called Section 124A, the “prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code, designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen."

“Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law,” he said. “If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote, or incite to violence. But the section under which Mr Banker and I are charged with one under which mere promotion of disaffection is a crime… I have studied some of the cases tried under it [Section 124A] and I know that some of the most loved of India’s patriots have been convicted under it. I consider it a privilege, therefore, to be charged under that section.” Justice Broomfield, while proceeding to pronounce the sentence, said, “Mr Gandhi, you have made my task easy in one way by pleading guilty to the charge. Millions look upon you as a saint. It is my duty to judge you as a man subject to the law, who has by his own admission broken the law.” He then went on to award the sentence to Gandhi.

“The judge then rose. Gandhi bade goodbye to his friends. Many of them wept but he remained calm and smiling,” writes Strangman in his book. “So ended the trial. I confess that I myself was not wholly unaffected by the atmosphere.” Although Gandhi was sentenced to six years in prison, he was released after two years because of medical reasons.

Why the British decided to arrest Gandhi

(In this excerpt from The Great Repression: The Story of Sedition in India (Penguin India) , Supreme Court lawyer Chitranshul Sinha provides a background on the events leading up to the prosecution and how the three articles became an excuse for the British to put Bapu in jail)

In April 1919, Gandhi had called off the satyagraha against the Rowlatt Act as it had led to violence in many parts of the country. Even in the face of the campaign of repression unleashed by the British government, Gandhi dissuaded his associates and followers from holding strikes or demonstrations against the government... In an announcement published in Sanj Vartaman on May 3, 1919, Mahatma Gandhi announced that he would resume the Satyagraha and Civil Disobedience Movement on July 1 of that year unless the Rowlatt Act was withdrawn by then.

He intended to extend the movement to Punjab, which was under repressive martial law and was still reeling from the horrors of Jallianwala Bagh. He exhorted the need to refrain from violence or rioting during the movement. The British government was convinced that Mahatma Gandhi had assumed absolute leadership of the ‘satyagraha sabha’, which they considered to be a secret society whose objective was to break laws and excite anti-government feelings in order to make governance of India impossible.

Ironically, the Rowlatt Act, the campaign against which brought Mahatma Gandhi to the forefront of the freedom movement in India, remained a non-starter and was effectively a dormant legislation which was never invoked.

On July 21, 1919, Gandhi called off the Civil Disobedience Movement "on account of indication of goodwill on the part of the Government and advice from many of his friends". This period was followed by the Khilafat Movement by Indian Muslims against the British government in 1920 (whose seeds were sown in 1919 itself). The movement had resulted from the defeat of Turkey at the hands of the British army in the WWI. Turkey was dispossessed of its lands and the Ottoman sultan of Turkey placed under the control of the allied powers led by the British.

Therefore, the allies became the real rulers of Turkey with the sultan reduced to a figurehead. This caused great resentment amongst Indian Muslims as they saw it as an attack against Islam because the sultan was considered the caliph of Islam. Gandhi backed the movement to the hilt as he saw it as a vehicle to unite Hindus and Muslims. He combined the Khilafat Movement led by the Ali brothers with his Non-cooperation Movement to create a bigger and better weapon against the British government.

The government took on the civil disobedience and non-cooperation juggernaut with its full might and restricted the freedom of speech and association. In early 1922, Mahatma Gandhi gave an ultimatum to the British government... He asked the government to revise its policy and set free political prisoners convicted of non-violent crimes, failing which he announced a campaign of mass civil disobedience to be launched from Bardoli in Gujarat.

The government rejected his demands, thereby laying the ground for a pan-Indian, non-violent Civil Disobedience Movement. The entire nation was galvanised and preparations made across all the presidencies and provinces. No one realised that their preparations would be in vain.

The events of February 5, 1922 ensured that the movement would be stillborn. A procession in a village named Chauri Chaura in the United Provinces was fired upon by police officers who shut themselves inside a police station to escape mob fury once they ran out of ammunition. The mob, however, did not relent and set the police station on fire. The officers, in their attempt to escape the blaze, were captured by the rampaging mob. Twenty-two persons were hacked to death and their bodies burnt in the blaze. The event sent shock waves across the nation.

As collateral damage, Mahatma Gandhi called off the Civil Disobedience and Non-cooperation Movements indefinitely… The government considered it an opportune moment to arrest Gandhi, something which it had not done during the movement for fear of mass reprisals. But they were emboldened by his loss of popularity and support and arrested him in Ahmedabad on March 10, 1922. (Research by Rajesh Sharma)

1947 September/ Partition violence

Sep 5, 2021: The Times of India

From: Sep 5, 2021: The Times of India

As the violence of Partition continued to take its toll, on September 1, 1947, Mahatma Gandhi began a fast until ‘sanity returned to Calcutta’. The city had remained largely peaceful as rioting flared in Bengal, but violence broke out there on August 31, leaving 50 dead and prompting Gandhi to go on a fast. He only had to fast for three days before representatives of Hindu and Muslim groups met him and laid down their arms. Before he began the fast, Gandhi had reportedly said, “I know I shall be able to tackle the Punjab too if I can control Calcutta”. A few days later, he travelled to Delhi with the intention of going further to Punjab, where much of the Partition violence was concentrated. But the situation in Delhi was so dire, he decided to stay on for several months before beginning what would be his final fast on January 13, 1948.

Gandhi ji’s last days

Rajmohan Gandhi, January 29, 2022: The Times of India

As 1948 opened, Gandhi was restless. His toil had not made much of a difference. When on January 1, a Thai visitor complimented him on India’s independence, Gandhi remarked: “Today not everybody can move about freely in the capital. Indian fears his brother Indian. Is this independence?”

Another disturbance was caused by a Cabinet decision to withhold the transfer of Pakistan’s agreed share (Rs 55 crore, or $115 million) of the “sterling balance” that undivided India held at independence.

Conflict in Kashmir was cited as the reason: Vallabhbhai Patel said publicly early in January that India could not hand over money to Pakistan “for making bullets to be shot at us”. But Gandhi was not convinced that a violent dispute entitled India to keep Pakistan’s money.

On January 11, he was shaken afresh when a group of Delhi’s Muslims asked him to arrange their “passage to England’ as they felt unsafe in India but were opposed to Pakistan and did not wish to go there.

That swaraj felt like a curse was the message also of a letter arriving at this time from Konda Venkatappayya of the Telugu country, a veteran freedom fighter whom Gandhi called an “aged friend”. Writing that he was “old, decrepit, with a broken leg, slowly limping on crutches within the walls of my house”, Venkatappayya referred to the moral degradation of Congress politicians who made money by protecting criminals, and added: “The people have begun to say that the British government was much better”. Gandhi found the letter “too shocking for words”.

On the morning of January 12, however, the agitated man found peace. The “conclusion flashed upon” him, Gandhi would say, that he must fast and not resume eating until there was “a reunion of hearts”. That winter afternoon, while sitting, as he put it, “on the sundrenched spacious Birla House lawn”, Gandhi wrote out, in English, a statement announcing and explaining the fast.

Sushila translated it into Hindustani and also read it out at the 5pm prayer meeting, for it was Monday, Gandhi’s “silent” day.

January 12, 1948: Though the voice within has been beckoning for a long time, I have been shutting my ears to it lest it might be the voice of Satan… The fast begins from the first meal tomorrow [Tuesday, January 13]… It will end when and if I am satisfied that there is a reunion of hearts of all communities brought about without any outside pressure, but from an awakened sense of duty. The reward will be the regaining of India’s dwindling prestige… I flatter myself with the belief that the loss of her soul by India will mean the loss of the hope of the aching, storm-tossed and hungry world…

Writing to his father late at night on January 12, Devadas, my father, pleaded against the fast:

You have surrendered to impatience… Your patient labour has saved thousands of lives… By your death you will not be able to achieve what you can by living. I would therefore beseech you to pay heed to my entreaty and give up your decision to fast. Admitting that the son’s final sentence had touched him, Gandhi asked Devadas to join in the prayer that “the temptation to live may not lead me into a hasty or premature termination of the fast”. A “very much upset” Vallabhbhai Patel offered to resign if that would prevent Gandhi’s fast, but Gandhi wanted Patel to continue. However, Gandhi raised with Patel the question of the Rs 55 crore. On the afternoon of January 14 the Cabinet met and decided to release the money, though Patel broke down before agreeing to the reversal.

India’s solemn obligation was discharged. This decision by the Indian Cabinet, which was led by Gandhi’s political “sons”, was likened by him to the change he had secured in 1932, in prison, from his majesty’s government in London. But the Cabinet decision did not suffice. There were other conditions to be met. The fast would continue. In his prayer talk on the evening of the 14th, Gandhi referred to Delhi’s significance and to a boyhood dream: January 14: Delhi is the capital of India… It is the heart of India... All Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Jews who people this country… have an equal right to it… Therefore, anyone who seeks to drive out the Muslims is Delhi’s enemy number one and therefore India’s enemy number one…

When I was young I never even read the newspapers. I could read English with difficulty and my Gujarati was not satisfactory. I have had the dream ever since then that if the Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Muslims could live in amity not only in Rajkot but in the whole of India, they would all have a very happy life. If that dream could be realised even now when I am an old man on the verge of death, my heart would dance. Children would then frolic in joy…

The Sikh ruler of Patiala, which had seen large-scale attacks on Muslims, asked Delhi’s Sikhs to help end Gandhi’s fast. A group of Hindus and Sikhs invited Muslims who had left for Karachi to return to Delhi. Rajendra Prasad, the Congress president, and Azad mobilised Delhi’s citizens for meeting Gandhi’s terms, which had been spelt out in detail.

Activity in Delhi was matched by an unexpected response in Pakistan, where prayers were offered in public and also “by Muslim women in the seclusion of their purda”. Leaders expressed “deep admiration and sincere appreciation” for Gandhi’s stand.

Through the Indian high commissioner in Karachi, which was then Pakistan’s capital, and Pakistan’s high commissioner in New Delhi, Jinnah sent a message urging Gandhi to ‘live and work for the cause of Hindu-Muslim unity in the two dominions’. However, an attack on January 13 on a refugee train at West Punjab’s Gujrat station killed or maimed hundreds of Hindus and Sikhs fleeing from the NWFP. Gandhi reacted realistically.

[If] this kind of thing continues in Pakistan (he said on 14 January), even if 100 men like me fasted, they would not be able to stop the tragedy that may follow.

Then, in the same remark, Gandhi challenged his people, Indians and Pakistanis, by recalling a well-known verse: The poet says, “If there is paradise, it is here, it is here.” He had said it about a garden. I read it ages ago when I was a child… But Paradise is not so easily secured. If Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs become decent, become brothers, then that verse can be inscribed on every door… If that happens in Pakistan, we in India shall not be behind them… Society is made up of individuals… If one man takes the initiative, others will follow and one can become many; if there is not even one there is nothing.

On January 18, the sixth day of the fast, over 100 persons representing different communities and bodies called on a shrivelled Gandhi at Birla House. Rajendra Prasad read from a declaration all had signed: We take the pledge that we shall protect the life, property and faith of the Muslims and that the incidents, which have taken place in Delhi will not happen again. We want to assure Gandhiji that the annual fair at Khwaja Qutbuddin’s Mazhar will be held this year as in the previous years. (Angry Hindus and Sikhs had earlier vowed to prevent this hoary observance, held on a revered thirteenth-century site.) Muslims will be able to move about in Subzi Mandi, Karol Bagh, Paharganj and other localities just as they could in the past. The mosques which… now are in the possession of Hindus and Sikhs will be returned. We shall not object to the return to Delhi of the Muslims who have migrated from here if they choose to come back and Muslims shall be able to carry on their business as before. We assure that all these things will be done by our personal effort and not with the help of the police or military.

Appeals for ending the fast were then made by Prasad, Maulana Azad, Zahid Husain (the Pakistani high commissioner), Ganesh Dutt, who said he spoke for the Hindu Mahasabha and the R S S, Harbans Singh, in the name of the Sikhs, and Khurshid and MS Randhawa for the Delhi administration.

Acceding to the appeals, Gandhi added that he would not “shirk another fast” if he found he had been deceived.

Brij Krishna thought that Gandhi’s shrunken and lined face looked radiant.

After prayers from five faiths were sung, there was complete silence as Maulana Azad handed a glass of orange juice to Gandhi, who accepted it with a long thin hand before asking all present to partake of fruit. Among those wiping a tear was Jawaharlal, who told Gandhi he had been secretly fasting himself from the previous day.

That day, January 18, 1948, Delhi was saved for the future as a city for all. Twelve days later, Gandhi would be killed as he walked to pray on the Birla House grounds. But the assassination only served to seal India’s pledge to be a secular state, and a nation for all its citizens, a pledge largely honoured — in law if not always on the ground — in the years that would follow.

Excerpted with permission from publisher, Aleph Book Company

Fasts

1925, after “moral lapse” among young Ashram boys and girls

Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

‘Moral Lapse’ That Made Gandhi Go On A Fast

On November 23,1925, after two days of agony, MK Gandhi decided to go on a fast for seven days. There was a “moral lapse” among the young boys and some girls at the Satyagraha Ashram at Sabarmati. This fast was to commence on November 24 and last up to November 30. This decision was taken neither in haste nor without the awareness of its consequences, both on his body and on the boys and girls and whose moral lapse had prompted this fast. The Phoenix Settlement in South Africa had “ashramic character”, especially after the advent of Satyagraha in 1906. The community at Sabarmati was ashramic, in the full sense. That is, each member was aware of the ashram observances and the ideal conduct that they were expected to strive towards, if not attain in every instance.

What was it about this community that its moral lapse prompted Gandhi on several occasions to undertake purificatory penance? In his account of an earlier lapse at Phoenix Settlement, Gandhi confessed that he was wounded. “News of an apparent failure in the great Satyagraha struggle never shocked me, but this incident came upon me like a thunderbolt. I was wounded.”

For Gandhi, untruth in the ashram was a symptom of a deep failing, a failing that could only be attributed to himself. It was a sign that the light with which he aspired to lead his life still eluded him. What he was required to do was reach deep within and seek to dispel the darkness. This he hoped and believed would purify himself and those around him. Before establishing the Satyagraha Ashram, first at Kocharab and later at Sabarmati, Gandhi had established two ashramlike communities in South Africa. Ashram-like, as he steadfastly refused to describe them as ashrams. One was merely a settlement the Phoenix Settlement — and the other a farm — the Tolstoy Farm. Phoenix was established in 1904 under the “Magic spell” of John Ruskin’s Unto This Last but acquired an ashram-like character only after 1906. It was in 1906 that Gandhi took the vow of brahmacharya, initially in the limited sense of chastity and celibacy. Gandhi says, “From this time onward I looked upon Phoenix deliberately as a religious institution.” Observance of a vrata, often inadequately translated as vow, is a defining characteristic of the ashram. It is only through the observances that a community becomes a congregation of co-religionists and a settlement becomes a place for experiments with truth.

The ashram and its community were Gandhi’s greatest experiment and also the site for his experiments. It was a community that had its foundations in truth. In absence of truth, or even in case of violation of it, the ashram could not be. It was simultaneously a community that aspired to Ahimsa, not only as a negation, as non-violence but as active working of love. This community sought to lead a life of non-stealing, which included in its understanding “Bread-Labour” and non-acquisition. This community sought to cultivate equability or Samabhava, with regard to religion and on the practice of untouchability. Samabhava, Gandhi knew, is possible only when the sense of Mamabhava, of “mine-ness”, of possession disappears. Gandhi had hoped that his ashram would be like the Sthitprajna, a person of equipose, a person whose intellect is secure as described in the Bhagvad Gita. “When it is night for all other beings, the disciplined soul is awake! When all other beings are awake it is the night for the seeing ascetic.” Such an ashram, Gandhi believed, was his only creation, the only measure by which he would be judged and would like to be judged. Writing at the conclusion of the 1925 fast, he said of the ashram, “It is my best and only creation. The world will judge me by its results.”

It was to this community that Gandhi chose to retreat each time he had to do soul-searching or dwell closer to Satyanarayan, Truth as God. Gandhi had one deeply felt need, desire, want and aspiration; to be an ashramite in the sense of living for a length of time in the communities that he had created. His oft repeated lament was that his work and obligation to myriad causes made him an itinerant ashramite. The ashram observances went with him, but the community of co-religionists could not. This was true not only of ashram at Sabarmati, but also of Phoenix and Tolstoy Farm.

The day the ashram at Sabarmati was founded — June 17, 1917 — Gandhi was far away in Motihari for his work on the Agrarian Inquiry Commission. From June 17, 1917, to March 12, 1930, when he left the ashram for the coastal village of Dandi, never to return, Gandhi spent a total of 1,520 days at the ashram. His most intense period of in-dwelling was from November 1925 to February 1929, when he lived at the ashram for 685 days. It was during this period that he wrote his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth and gave discourses on each verse of the Gita and also translated it in Gujarati.’

With passage of time Gandhi’s need to dwell within ashramic community decreased, till such time that during his lonely pilgrim through Noakhali that reminded Sarojini Naidu of Via Dolorosa, the path that Jesus of Nazareth walked carrying his cross, he chose to be alone with only two companions N K Bose and Manu Gandhi. He had been never been so isolated from people ever since his return to India in 1915, not even during his incarcerations. His need for the physical space called ashram and community decreased as his reliance upon the ashramic observances increased, as did his devotion to Ramanama. Ashram was what lived within him, his Anataryami, the dweller within that guided him.

(Suhrud has recently published a critical edition of M K Gandhi’s Autobiograhy and The Diary of Manu Gandhi)

Food

The Mahatma’s Experiments

Vikram Doctor, Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

In late 1888 a hungry young Indian man could be found roaming the streets of London. Mohandas Gandhi was there to become a barrister, but his more urgent need was to find food to eat. He had promised his mother never to eat non-vegetarian food, but in his lodgings that meant a dreary diet of oatmeal porridge and bread.

Gandhi was searching for the few vegetarian restaurants in the city and finally found the Central Vegetarian Restaurant quite close to Fleet Street. “The sight of it filled me with the same joy that a child feels on getting a thing after its own heart,” he wrote in My Experiments with Truth. He entered and had his first proper meal in the UK.

Gandhi also bought a book at the restaurant: Henry Salt’s A Plea for Vegetarianism. Salt was a pioneer advocate for animal rights and his book made a deep impression on Gandhi. Vegetarianism in the UK then was not just about food, but brought together many alternate causes, like feminism, nature therapy, sexual liberation, theosophy, animal rights and, crucially for Gandhi, anti-colonialism.

Gandhi went to the restaurants (there was another called The Porridge Bowl) to eat but started getting interested in the ideas he found there. He made a friend in Dr Josiah Oldfield, the editor of the journal of the London Vegetarian Society who encouraged the shy young Indian to meet people through vegetarianism — one was Sir Edwin Arnold, the translator of the Gita, which Gandhi had just started reading — and also to contribute his first published works, on Indian vegetarianism, to the journal.

Another vegetarian contact in London was the Gujarati writer Narayan Hemchandra. He had arrived in the UK recently, but spoke no English and sought out Gandhi to help him communicate — and find food. But when Gandhi offered him Westernised food like carrot soup Hemchandra turned up his nose. He insisted he needed dal and “once he somehow hunted out moong, cooked it and brought it to my place. I ate it with delight.” Hemchandra was unapologetically Indian, even wearing a dhoti in the street, despite being jeered at, and his self-confidence in his own identity was to have a profound influence on Gandhi.

Gandhi’s link with the Vegetarian Society continued in South Africa. He became their agent to promote vegetarianism there and, while converts were few, people were generally interested enough to hear the young Indian talk passionately the subject, and this helped Gandhi overcome his shyness. And it was at a vegetarian restaurant in Johannesburg that he met Henry Polak and Hermann Kallenbach who would both become vital early supporters of his work.

Looking back on those years, while writing Satyagraha in South Africa in 1926, Gandhi wrote: “I have been fond for about the last 35 years of making experiments in dietetics from the religious, economic and hygienic standpoints. This predilection for food reform still persists.” South Africa was where Gandhi started living in a commune, and for the rest of his life would live in a revolving community of people, many of whose diets he supervised in an extended experiment on eating.

It is startling how much food features in Gandhi’s collected works. He can be writing to the Viceroy or Congress politicians, and the next letters might be instructions to a follower on what to eat, requests to procure the fruit and leafy greens that formed a large part of his diet or suggestions on how to promote village foods, like oil crushed in traditional ghanis. Gandhi was keenly interested in British attempts to improve Indian agriculture and also corresponded with Dr Robert McCarrison, Director of Nutritional Research in India who was doing pioneering work on nutritional deficiencies in diets.

Visitors often ended up talking about food, like Paramahansa Yogananda, author of Autobiography of a Yogi, who recommended avocados to Gandhi (and sent him seedlings from California, but they all died on the way). All this interest was strictly on food as fuel for a healthy body, and most visitors also noted how dire the food served in Gandhi’s ashrams tasted. One of the few to say this was his grand-daughter Ela who once told him in exasperation that Sevagram should be called Kadugram since all they seemed to eat was pumpkins. Gandhi laughed and gave instructions for different vegetables to be cooked.

This fascination with food might make it seem odd that Gandhi is famous for his extended fasts. But these extended periods of food denial are extensions of his basic interest in feeding. Gandhi knew that food, like clothing, was one of the few essentials for humans and that gave anything to do with it power. Wilfully refusing to eat affirmed that power, and even just fasting for a fixed time was a kind of self-purification for him.

It also meant that what one ate mattered, which was why Gandhi vowed not drink cow’s milk after he learned how they were ill-treated to produce it. But his body rebelled. Gandhi had few other source of protein — he was suspicious of pulses for forming gas — and needed dairy to survive. So, at Kasturba’s suggestion, he agreed to drink goat’s milk since he reasoned he was not thinking of goats when he made the vow. But Gandhi always felt guilty about such a hair-splitting reasoning — and procuring lactating goats wherever he went would become a major headache for his assistants like Mirabehn.

Today, Gandhi would be vegan. He inquired about the potential for plant-based milks and soy proteins, but these were not widely developed in India at that time. Several times in his life he tried raw food diets and tried other foods like caffeine-free tea made from roasted wheat or wheat-free bread made from banana flour that are popular diet options today. But Gandhi also had a larger perspective on diets that might be worth recalling for those who might as food focused as he was.

Gandhi spelled this out in a speech he gave in 1931 when he was back in London for the Second Round Table Meeting. He was given a reception by Vegetarian Society, where his journey had begun, and he sat on stage next to Henry Salt, whose book had provided a catalyst. It was a moment to savour yet he used it to recommend his vegetarian friends remember the value of humility. In his experience, he said, “I found also that health was by no means the monopoly of vegetarians… and that nonvegetarians were able to show, generally speaking, good health.”

Gandhi recalled debates from his early days at the Vegetarian Society where people argued furiously, even divisively, for the benefit of one diet versus another. He felt this was a problem since one didn’t necessarily become a better person because of what one ate. Believing someone was inferior for eating meat was wrong — and also a tactical mistake since it would made it harder to convince them to become vegetarian someday. Gandhi felt what was needed with food was both mindfulness and moderation, which is a message that is still relevant today.

Films about the Mahatma

From: Sep 29, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Films about the Mahatma

Friends, international

From: Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

Hermann Kallenbach and Gandhi

The Times of India, Sep 30 2015

Kounteya Sinha

Kallenbach was Gandhi's `wailing wall': Researcher

Priceless documents discovered in Israel have revealed, for the first time ever, the role a Jewish architect played in creating the phenomenon that was Mahatma Gandhi. When Lithuania unveils the statue of Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach in Rusne on October 2, researcher Shimon Lev of Jerusalem's Hebrew University, who has extensively studied the archive, will reveal to the world the story of the deep friendship between India's father of the nation and his “soulmate“. Excerpts from Lev's exclusive interview to TOI:

How did you get your hand on the Gandhi Kallenbach documents?

Some years ago, I wrote a series of articles about a hiking trail across Israel. During my hike, in a cemetery near the Sea of the Galilee, I went to see the neglected grave of Kallenbach.I published a few lines about him, which resulted in an invitation from his niece, Mrs Isa Sarid, to “have a look“ at Kallenbach's archive. The archive was located in a tiny room in a small apartment up on Carmel Mountain in Haifa. On the shelves were numerous files carrying the name of Gandhi. One of the less known chapters of Gandhi's early biography was waiting for a researcher to pick up the challenge. Finding an archive like this might be the fantasy of any historian.

You call Gandhi and Kallenbach soulmates. Were they truly?

Their friendship was characterized by mutual efforts towards personal, moral and spiritual development, and a deep commitment to the Indian struggle. On a personal level, Kallenbach provided Gandhi with sound emotional support. He was Gandhi's confidant, with whom Gandhi could share even the most personal matters, such as troubles with his wife and children. Gandhi's letters to Kallenbach and documents in the archive reveal their relationship to be an extremely complex and highly unconventional one, with elements of political partnership and surprisingly strong personal ties for two such dissimilar men.

Any interesting anecdotes fom their lives that show their proximity to each other?

Kallenbach was Gandhi's “wailing wall“. When Harilal, Gandhi's eldest son, ran away to Delgoa Bay on his way to India in an effort to get the formal education his father denied him, it was Kallenbach who was sent to bring him back.

What was the unique historical significance in their encounter?

I think that one of most important contributions of Kallenbach is the establishment of Tolstoy Farm in 1910.It is impossible to over-emphasize the influence of the experiment on the formulation of Gandhi's spiritual and social ideologies. But what made their story even more unique was the “second round“, which took place in 1937, when Hitler was already in power. Kallenbach was asked by future Israeli PM Moshe Sharet to brief Gandhi on Zionism, hoping to get his support for a Jewish homeland. That is when Gandhi came out with the disturbing proclamation, The Jews, in 1938, in which he called the Jews to begin civil resistance and be ready to die as a result. Gandhi used Kallenbach as an example of the tension between his nonviolence doctrine and what was going on in Europe.

“I happen to have a Jewish friend...He has an intellectual belief in non-vi olence. But he says he cannot pray for Hitler. I do not quarrel with him over his anger...“

So the chronicles of their relationship traverse the dramatic events of the first half of the 20th century.

What was unique about this relationship and why isn't their relationship so widely known?

Kallenbach was Gandhi's most intimate European supporter. He was the one who Gandhi could mostly trust.

There may be a number of reasons for the general disregard of Kallenbach's contribution. Their forced separation due to Kallenbach's confinement in a British internment camp during World War I is partly to blame.Had Kallenbach gone to India, it is probable that he would have become the administrative manager of Gandhi's Indian ashrams. Moreover, the scarcity of first-hand sources regarding their relationship makes the study of his influence difficult.

Who inspired whom in the relationship and how?

Obviously, Gandhi was the one who inspired everyone else around him, including Kallenbach. He was the spiritual authority no doubt about this. Kallenbach's Jewish family regarded him as one trapped by “Gandhi's spell“.

How will this statue help in telling their stories?

Well, definitely it will make their fascinating story more known. I claim that it is impossible to understand Gandhi without understanding his relationships with those close to him.Between 1906 and 1909, Gandhi underwent an extremely significant transformation, the result of which was that his doctrine became fully solidified. His partner in these crucial years was Herman Kallenbach.

Nelson Mandela on the Mahatma

Nelson Mandela, Divinely Inspired Extraordinary Leader, Jan 30 2017: The Times of India

Mahatma Gandhi was no ordinary leader. There are those who believe he was divinely inspired, and it is difficult not to believe with them. He dared to exhort non-violence in a time when the violence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had exploded on us; he exhorted morality when science, technology and the capitalist order had made it redundant; he replaced self-interest with group interest without minimising the importance of self. In fact, the interdependence of the social and personal is at the heart of his philosophy . He seeks the simultaneous and interactive development of the moral person and society .

His philosophy of Satyagraha is both a personal and social struggle to realise the Truth, which he identifies as God, the Absolute Morality . He seeks this Truth, not in isolation, self-centredly , but with the people.

He sacerises his revolution, balancing the religious and the secular.He resuscitated the culture of the colonised; he revived Indian handicrafts and made these into an economic weapon against the coloniser in his call for swadeshi the use of one's own and the boycott of the oppressor's products, which deprive the people of their skills and their capital.

Gandhi's insistence on self-sufficiency is a basic economic principle that, if followed today , could contribute significantly to alleviating Third World poverty and stimulating development.

Gandhi predated Frantz Fanon and the black-consciousness movements in South Africa and the US by more than a half century and inspired the resurgence of the indigenous intellect, spirit and industry .

Gandhi rejects the Adam t Smith notion of human nature as motivated by self-interest and brute needs and returns us to our spiritual dimension with its impulses for nonviolence, justice and equality .

He exposes the fallacy of the claim that everyone can be rich and successful provided they work hard. He points to the millions who work themselves to the bone and still remain hungry .

He seeks an economic order, alternative to the capitalist and communist, and finds this in Sarvodaya based on Ahimsa non-violence.

He rejects Darwin's survival of the fittest, Adam Smith's laissez-faire and Karl Marx's thesis of a natural antagonism between capital and labour, and focusses on the inter dependence between the two.

He believes in the human capacity to change and wages Satyagraha against the oppressor, not to destroy him but to transform him, that he cease his oppression and join the oppressed in the pursuit of Truth.

We in South Africa brought about our new democracy relatively peacefully on the foundations of such thinking, regardless of whether we were directly influenced by Gandhi or not.

Gandhi is not against science and technology , but he places priority on the right to work and opposes mechanisation to the extent that it usurps this right ... He seeks to keep the individual in control of his tools, to maintain an interdependent love relation between the two, as a cricketer with his bat or Krishna with his flute. Above all, he seeks to ... restore morality to the productive process.

At a time when Freud was liberating sex, Gandhi was reining it in; when Marx was pitting worker against capitalist, Gandhi was reconciling them; when the dominant European thought had dropped God and soul out of the social reckoning, he was centralising society in God and soul; at a time when the colonised had ceased to think and control, he dared to think and control; and when the ideologies of the colonised had virtually disappeared, he revived them and empowered them with a potency that liberated and redeemed.

Gandhi and the states

Chhattisgarh

From: Oct 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Mahatma Gandhi's visits in Chhattisgarh

Goals

Independence from Britain and from casteism

Sunil Khilnani, Oct 2, 2019: The Times of India

Sunil Khilnani is director of the King’s College London India Institute and coined the phrase, ‘the idea of India’

Until his assassination in 1948 by a Hindu militant with R S S connections, Gandhi directed his abilities towards two worldhistorical tasks. The first was to undermine the largest empire in human history. The second was to challenge the world’s most anti-egalitarian, hierarchical society, one in which violence defined and permeated its daily life. He was, that’s to say, taking on Britain and India at once.

That first ambition he lived, just, to see completed — though amidst disarray that plunged him into despair, as the violence he sensed coursing through in Indian society burst its runnels. But the second enterprise remains as incomplete as it ever was.

Among those of his arguments that proved, in the kindest gloss, over-optimistic centered on caste. Gandhi chose to see the projection of caste stigma as simple instances of individual moral failing and myopia among the upper castes. Just as he’d shamed the British into retreat, he believed he could shame India’s elites and non-Dalit castes into treating better those whom they were oppressing. But shame doesn’t come easily to elites of any kind, and especially not to our own. After all, they’ve been squatting on the top of the heap longer than most elites anywhere.

Ambedkar knew that well. Yet Gandhi entirely ducked Ambedkar’s profound insight: that caste, with its structure of graded inequality (a structure that was psychologically internalised at both the individual and collective level), was India’s distinct contribution to human oppression. It could only be blown apart by Dalits acting for themselves. Not upper caste self-reform, but Dalit self-assertion just might enable the birth of a new community of Indians who could be citizens together not just in their shared right to vote, but with actual social equality and common fraternity.

Gandhi was too hopeful in another of his core beliefs, that he could separate religion and violence — as his own fate made desperately plain. He felt he could release the scriptural declarations of tolerance, peace and diversity that feature in a variety of religious traditions and use such better-angels concepts to tame the violence which religious belief also entails. His was a brave effort to counter the weight of history’s evidence, previous and since, that there may be, between faith and bloodshed, a near-ineliminable connection. The only thing that can weaken that connection, we also know from history, is a state that refuses to belong to any religion — especially when that religion forms a social majority.

In other lines of argument, though, Gandhi’s radar seemed to pick up future dangers. For one, roughly a century before Twitter and TikTok, he understood the vulnerable circuits of our modern minds and our addiction to distraction. In ‘Hind Swaraj’, he wrote of how easy it was for a person’s mind to become a “restless bird”, flitting constantly in its cage: “the more it gets the more it wants, and still remains unsatisfied.”

He foresaw as well the ecological catastrophe we are now approaching fast. “God forbid that India should ever take to industrialisation after the manner of the West”, Gandhi wrote more than 90 years ago. If it did, “it would strip the world bare like locusts.”

One of Gandhi’s cardinal convictions was that freedom for societies such as India meant the liberty not to ape the west. Today we’re aping hard on consumption, our economists consulting and advising on how to increase sagging consumption levels. What can we do to improve weak vehicle sales in time for the fresh air season of Diwali: One can scroll many such articles lately when caught in a three-hour traffic snarl. In the (now not so) long run, we’d do better to let another passage from Gandhi ring in our heads: “Formerly, men were made slaves under physical compulsion. Now they are enslaved by temptation of money and of the luxuries that money can buy.”

By rights, this and other of Gandhi’s rebukes should make us stumble a bit in our unthinking routines and ideological enthusiasms, just as we remember that, in his own experiments and ideas, our great man stumbled too. To entomb our heroes’ memories in soft gauze, as we so often do, is to hide the most revealing edges. So it seems to me that Gandhi’s 150th birthday is a fine occasion to unwrap him: to open ourselves up to the incitements of this most unusual figure in our history, and keep on arguing with him.

Ideological differences

Dr Ambedkar, Vir Savarkar

Vaibhav Purandare, Sep 28, 2019: The Times of India

For one so wedded to peace, Mahatma Gandhi’s constant companion in life was the tempest. Often it blew all too ferociously, inviting for him charges of preaching from the pulpit, sidetracking the freedom movement in favour of obscure moral questions, pandering to the Hindu majority or Muslim minority, talking down to Dalits and talking up the virtues of non-violence to the point of discrediting India’s armed revolutionaries.

His protracted battles with the British and with Jinnah are well known. So is the exasperation his proteges like Nehru, Patel and Bose sometimes felt over his approach. Unfairly for both Gandhi and his opponents, though, Indian textbooks, for long after Independence, barely informed new generations about his differences and debates with two of his staunchest and most unsparing Indian critics: BR Ambedkar and VD Savarkar.

Savarkar appeared on the scene before Ambedkar, when Gandhi was in South Africa. As the young leader of a group of patriotic Indians in London, he met Gandhi first in 1909 when the latter visited the British capital, and together, they heaped praise on each other at a public meeting. Both then affirmed their faith in Hindu-Muslim unity, but they had fundamental differences: Savarkar embraced revolutionary methods in the struggle for liberation, and Gandhi abhorred violence. On his way back to South Africa, Gandhi wrote on the ship his tract ‘Hind Swaraj’, in which he voiced his disapproval of armed revolution. Savarkar’s reply: “We aren’t fond of violence, but if constitutional methods are denied to us, how else do we fight for our rights?”

Soon, Savarkar was dispatched to Kaala Paani. By the time he was back in a jail on the mainland in 1921 and later placed in conditional confinement in 1924, everything had changed. Gandhi had taken over the Swaraj movement and got the masses to adopt his mantra of non-violence. Worse for Savarkar — now a man transformed after experiences with Pathan jail staffers in the Andamans — Gandhi had openly backed the “pan-Islamic” Khilafat agitation. This was not Khilafat but an “aafat (trouble)”, Savarkar said, and termed the non-cooperation movement and its sudden withdrawal as “eccentric and defeatist politics”.

They discussed their differences in 1927 during Gandhi’s visit to Savarkar’s Ratnagiri home and agreed to go separate ways. Savarkar then wrote a series of essays assailing the Mahatma for his “hollow” Ahimsa absolutism, his “fetish” for goat’s milk, his “needless meddling in politics (in the 1930s) after declaring he’d focus on the charkha,” his opposition to railways and modern medicine, and his invocation of “Ram Rajya” and “cow protection”. Though by now author of the tract Hindutva, Savarkar was no believer in “gau mata”; his Hindutva was political. Gandhi had previously made an appeal for Savarkar’s release from Kaala Paani; asked in the mid-1930s to issue another plea for end of his conditional confinement, he refused, saying “my way of moving in such matters is different”.

Ambedkar, who earned his spurs at Columbia University, shared with Savarkar a dislike for Gandhian projections of a religious morality. Both also felt Gandhi was wrong in defending the caste system. Ambedkar saw the word ‘Harijan’, coined by Gandhi for the Depressed Classes, as patronising and left his first meeting with the Mahatma in 1931 in a huff after Gandhi opposed the Raj’s plan for separate electorates for the ‘outcastes’. Ambedkar was firm on political safeguards, while Gandhi considered the “political separation of Untouchables” from Hindus “suicidal”. Months later, at the Second Round Table Conference, Ambedkar accused Gandhi of “treachery” against the Depressed Classes, said he had “created a scene” during debate, and dubbed him “petty-minded”. Gandhi’s “fast unto death” amid this row, and the 1932 Poona Pact between the two caused a permanent breach — Dalits got more seats but no separate electorates.

The paths of Ambedkar and Savarkar too diverged drastically, with the former declaring he was “born a Hindu but wouldn’t die as one”, and Savarkar in 1937 assuming leadership of Hindu Mahasabha. Both, however, struggled to create an alternative pole in Indian politics even as they intensified attacks on Gandhi. Ambedkar called Gandhi’s politics — like Savarkar once had — “hollow”, “noisy”, “the most dishonest … in the history of Indian polity”, and Savarkar criticised him for his “Quit-India-but-keep-your-arms-here plea” to the British and for giving parity to Jinnah in negotiations.

Savarkar and his followers ultimately blamed Gandhi for “presiding over Partition”. When the Constitution took shape, Ambedkar, for his part, was relieved India hadn’t adopted a Gandhian Constitution with the village (in Ambedkar’s words “a den of casteism and superstition”) as a central unit, but one in the European-American tradition. Still, Ambedkar struggled politically against Congress until his death in 1956, and Savarkar’s arrest in the Gandhi assassination case ruined his political career in spite of his acquittal.

To Gandhi’s credit, he had sought to engage with both critics while still on talking terms with them, telling them he’d visit their place for discussions if it were inconvenient for them to come over. With Savarkar, there was at least some initial warmth; with Ambedkar, there was none.

International recognition during his lifetime

The USA in the 1930s

Nandini Rathi, Aug 25, 2023: The Indian Express

“Between 1905 and 1947, there was a propaganda war between Indian nationalists and British officials for the support of Americans,” writes South Asia historian Leonard Gordon. Until the 1920s, American newspapers heavily relied upon their London correspondents, the British Press and Reuters (which had a mutually beneficial, monopoly agreement with the Government of India for preferential access) for news about India. The news was hence generally from the British perspective and news obfuscation attempts on events that cast the Raj in a poor light, like details of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, usually succeeded.

Gandhi first surfaced in the American awareness around 1920 when his first non-cooperation campaign struck a redoubtable blow to the the British raj and since then he was, in Lloyd Rudolph’s words, “revered and reviled”. His ideas of a freedom struggle appeared unfamiliar and exotic to Americans — fascinating to some and threatening to others.

The newsmaking Mahatma of the 1930s

Gandhi’s iconic Dandi March in 1930 was a watershed moment in directing the western media spotlight on India. The event became a launchpad for sustained, popular American media focus on India and on Gandhi in particular. Indeed it was designed to be such. Media scholar Chandrika Kaul points out that before embarking on the march, and again upon breaking the salt laws, Gandhi had been in touch with the Director of Indian Independence League in New York, directing him to publicise the protest. And so the New York Times published Gandhi’s appeal under the headline, “Gandhi Asks Backing Here: Urges Expression of Public Opinion for India’s Right to Freedom,” in which he exhorted American sympathisers of his cause for a “concrete expression of public opinion in favour of India’s inherent right to independence and complete approval of the non-violent means adopted by the Indian National Congress”.

The dramatisation of Indian nationalism in 1930 in the form of Salt Satyagraha prompted the Time magazine to feature Gandhi on his cover, under the title, “Saint Gandhi”. The cover feature titled “A Pinch of Salt” argued that had an English politician in a loin cloth walked 80 miles to London barefoot, “the Englishmen would have thought him mad”. However, as Gandhi “trudged along last week … Englishmen were not amused but desperately anxious.”

Original American reporting on India intensified thereafter, with various newspapers and periodicals such as the Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily News, Washington Post, Nation, Time etc. along with the agencies Associated Press (AP) and United Press (UP) consolidating their resources and correspondents to that end. This is not to say that all press coverage of India and Gandhi was supportive — the British imperialism also had its champions among American publications.

The following year, in 1931, Gandhi, who was almost unknown in the US until a decade earlier, also became Time Magazine’s Man of the Year. The feature sizzled on the forefront of American press for several days as breaking of the salt law was compared to an iconic event in American freedom movement: the Boston Tea Party. By the 30s, Gandhi had become a permanent nuisance to the British Raj. He emerged in the western world, especially in the US, as enormously newsworthy. In addition to spotlighting his appearance and personality, Gandhi’s challenge to the British imperial juggernaut was given a dramatic treatment akin to an unfolding David and Goliath in many publications.