Mumbai attacks, 26/ 11 2008

(→In brief) |

(→In brief) |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

4. Attacks were carried out by terrorists at Railway station, Leopold Cafe, Taj Mahal Palace & Tower Hotel, Oberoi Trident Hotel, Metro Cinema, Cama and Albless Hospital and Nariman House. | 4. Attacks were carried out by terrorists at Railway station, Leopold Cafe, Taj Mahal Palace & Tower Hotel, Oberoi Trident Hotel, Metro Cinema, Cama and Albless Hospital and Nariman House. | ||

| − | |||

5. The terrorists used automatic weapons and grenades in the attacks. | 5. The terrorists used automatic weapons and grenades in the attacks. | ||

| Line 276: | Line 275: | ||

After the 26/11 attacks, the government got Israeli authorities to share a complete list of Chabad Houses and Jewish centres across India. Requisite security arrangements were put in place. | After the 26/11 attacks, the government got Israeli authorities to share a complete list of Chabad Houses and Jewish centres across India. Requisite security arrangements were put in place. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =The Taj Mahal Hotel: The happenings == | ||

| + | [https://www.indiatoday.in/lifestyle/people/story/former-taj-head-chef-hemant-oberoi-on-26-11-we-lost-more-staff-than-guests-1622709-2019-11-26 Nov 26, 2019 ''India Today''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the upcoming drama Hotel Mumbai (releasing November 29), Anupam Kher plays Hemant Oberoi, head chef of the Taj Mahal Palace & Towers, whose leadership skills are tested after the hotel is attacked on November 26, 2008. The film shows how Oberoi and his staff kept over a hundred guests safe in the exclusive Chambers lounge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That night, head chef Hemant Oberoi would go on to lose seven of his staff, all of whom were shot in the kitchen. Oberoi spoke to IndiaToday.in on the 11th anniversary of the tragedy that changed Mumbai forever about what the sacrifices meant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "You will remember the colleagues who laid down their lives and appreciate what they have done for the company," said Oberoi, who returned to his workplace on November 29, 2008, a few hours after the siege ended. | ||

| + | |||

| + | "If I had not moved on, my team wouldn't have. If they would see their leader shattered and broken, they would have given up," said Oberoi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Oberoi was in the hotel - shuttling between the Chambers lounge and his office, only a few steps away - until November 27 morning, when he left along with 17 of his staff members. But this was only after at least 150 guests were rescued, before 3.45 am. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Oberoi could have left much earlier if he wanted to. Merryweather Road, he said, was only 20 seconds away. "We went out three times to call the cops to protect us and thereby help us take out the guests," he said. "But they didn't have orders." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Oberoi says he couldn't have done it without the support of his staff which included Aziz, an employee on dialysis, who refused to leave without him. "We lost more staff than guests," added Oberoi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Remembering the scene on November 29 that year, Oberoi said that there was no electricity but the brutality of the attack was evident all over. "There were blood stains, mobiles and shoes were lying around," he said. "I have seen Wasabi counter smouldering." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Oberoi, who worked with the Taj group for 42 years until he left in 2016, currently runs his own restaurant in Mumbai. He is almost done with his book, My Spice Journey, which chronicles his 45-year-long culinary career. At least eight of the 150 odd pages, he said, are on the 26/11 attacks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ask him of how he held it together in such a crisis, his reply is, "We have become so selfish that we want to save our lives and not others. I strongly believe that karma comes back to you.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Head chef Hemant Oberoi’s recollections== | ||

| + | === The ordinary heroes of the Taj === | ||

| + | [https://hbr.org/2011/12/the-ordinary-heroes-of-the-taj Rohit Deshpande and Anjali Raina Dec 2011 ''Harvard Business Review''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On November 26, 2008, Harish Manwani, chairman, and Nitin Paranjpe, CEO, of Hindustan Unilever hosted a dinner at the Taj Mahal Palace hotel in Mumbai (Taj Mumbai, for short). Unilever’s directors, senior executives, and their spouses were bidding farewell to Patrick Cescau, the CEO, and welcoming Paul Polman, the CEO-elect. About 35 Taj Mumbai employees, led by a 24-year-old banquet manager, Mallika Jagad, were assigned to manage the event in a second-floor banquet room. Around 9:30, as they served the main course, they heard what they thought were fireworks at a nearby wedding. In reality, these were the first gunshots from terrorists who were storming the Taj. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The staff quickly realized something was wrong. Jagad had the doors locked and the lights turned off. She asked everyone to lie down quietly under tables and refrain from using cell phones. She insisted that husbands and wives separate to reduce the risk to families. The group stayed there all night, listening to the terrorists rampaging through the hotel, hurling grenades, firing automatic weapons, and tearing the place apart. The Taj staff kept calm, according to the guests, and constantly went around offering water and asking people if they needed anything else. Early the next morning, a fire started in the hallway outside, forcing the group to try to climb out the windows. A fire crew spotted them and, with its ladders, helped the trapped people escape quickly. The staff evacuated the guests first, and no casualties resulted. “It was my responsibility….I may have been the youngest person in the room, but I was still doing my job,” Jagad later told one of us.Elsewhere in the hotel, the upscale Japanese restaurant Wasabi by Morimoto was busy at 9:30 PM. A warning call from a hotel operator alerted the staff that terrorists had entered the building and were heading toward the restaurant. Forty-eight-year-old Thomas Varghese, the senior waiter at Wasabi, immediately instructed his 50-odd guests to crouch under tables, and he directed employees to form a human cordon around them. Four hours later, security men asked Varghese if he could get the guests out of the hotel. He decided to use a spiral staircase near the restaurant to evacuate the customers first and then the hotel staff. The 30-year Taj veteran insisted that he would be the last man to leave, but he never did get out. The terrorists gunned him down as he reached the bottom of the staircase. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When Karambir Singh Kang, the Taj Mumbai’s general manager, heard about the attacks, he immediately left the conference he was attending at another Taj property. He took charge at the Taj Mumbai the moment he arrived, supervising the evacuation of guests and coordinating the efforts of firefighters amid the chaos. His wife and two young children were in a sixth-floor suite, where the general manager traditionally lives. Kang thought they would be safe, but when he realized that the terrorists were on the upper floors, he tried to get to his family. It was impossible. By midnight the sixth floor was in flames, and there was no hope of anyone’s surviving. Kang led the rescue efforts until noon the next day. Only then did he call his parents to tell them that the terrorists had killed his wife and children. His father, a retired general, told him, “Son, do your duty. Do not desert your post.” Kang replied, “If it [the hotel] goes down, I will be the last man out.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Three years ago, when armed terrorists attacked a dozen locations in Mumbai—including two luxury hotels, a hospital, the railway station, a restaurant, and a Jewish center—they killed as many as 159 people, both Indians and foreigners, and gravely wounded more than 200. The assault, known as 26/11, scarred the nation’s psyche by exposing the country’s vulnerability to terrorism, although India is no stranger to it. The Taj Mumbai’s burning domes and spires, which stayed ablaze for two days and three nights, will forever symbolize the tragic events of 26/11. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the onslaught on the Taj Mumbai, 31 people died and 28 were hurt, but the hotel received only praise the day after. Its guests were overwhelmed by employees’ dedication to duty, their desire to protect guests without regard to personal safety, and their quick thinking. Restaurant and banquet staff rushed people to safe locations such as kitchens and basements. Telephone operators stayed at their posts, alerting guests to lock doors and not step out. Kitchen staff formed human shields to protect guests during evacuation attempts. As many as 11 Taj Mumbai employees—a third of the hotel’s casualties—laid down their lives while helping between 1,200 and 1,500 guests escape. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At some level, that isn’t surprising. One of the world’s top hotels, the Taj Mumbai is ranked number 20 by Condé Nast Traveler in the overseas business hotel category. The hotel is known for the highest levels of quality, its ability to go many extra miles to delight customers, and its staff of highly trained employees, some of whom have worked there for decades. It is a well-oiled machine, where every employee knows his or her job, has encyclopedic knowledge about regular guests, and is comfortable taking orders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Even so, the Taj Mumbai’s employees gave customer service a whole new meaning during the terrorist strike. What created that extreme customer-centric culture of employee after employee staying back to rescue guests when they could have saved themselves? What can other organizations do to emulate that level of service, both in times of crisis and in periods of normalcy? Can companies scale up and perpetuate extreme customer centricity? | ||

| + | Our studies show that the Taj employees’ actions weren’t prescribed in manuals; no official policies or procedures existed for an event such as 26/11. Some contextual factors could have had a bearing, such as India’s ancient culture of hospitality; the values of the House of Tata, which owns the Taj Group; and the Taj Mumbai’s historical roots in the patriotic movement for a free India. The story, probably apocryphal, goes that in the 1890s, when security men denied J.N. Tata entry into the Royal Navy Yacht Club, pointing to a board that apparently said “No Entry for Indians and Dogs,” he vowed to set up a hotel the likes of which the British had never seen. The Taj opened its doors in 1903. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Still, something unique happened on 26/11. We believe that the unusual hiring, training, and incentive systems of the Taj Group—which operates 108 hotels in 12 countries—have combined to create an organizational culture in which employees are willing to do almost anything for guests. This extraordinary customer centricity helped, in a moment of crisis, to turn its employees into a band of ordinary heroes. To be sure, no single factor can explain the employees’ valor. Designing an organization for extreme customer centricity requires several dimensions, the most critical of which we describe in this article. | ||

| + | '''A Values-Driven Recruitment System''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group’s three-pronged recruiting system helps to identify people it can train to be customer-centric. Unlike other companies that recruit mainly from India’s metropolitan areas, the chain hires most of its frontline staff from smaller cities and towns such as Pune (not Mumbai); Chandigarh and Dehradun (not Delhi); Trichirappalli and Coimbatore (not Chennai); Mysore and Manipal (not Bangalore); and Haldia (not Calcutta). According to senior executives, the rationale is neither the larger size of the labor pool outside the big cities nor the desire to reduce salary costs, although both may be additional benefits. The Taj Group prefers to go into the hinterland because that’s where traditional Indian values—such as respect for elders and teachers, humility, consideration of others, discipline, and honesty—still hold sway. In the cities, by contrast, youngsters are increasingly driven by money, are happy to cut corners, and are unlikely to be loyal to the company or empathetic with customers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''The Taj Group prefers to recruit employees from the hinterland because that’s where traditional Indian values still hold sway.’'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group believes in hiring young people, often straight out of high school. Its recruitment teams start out in small towns and semiurban areas by identifying schools that, in the local people’s opinion, have good teaching standards. They call on the schools’ headmasters to help them choose prospective candidates. Contrary to popular perception, the Taj Group doesn’t scout for the best English speakers or math whizzes; it will even recruit would-be dropouts. Its recruiters look for three character traits: respect for elders (how does he treat his teachers?); cheerfulness (does she perceive life positively even in adversity?); and neediness (how badly does his family need the income from a job?). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The chosen few are sent to the nearest of six residential Taj Group skill-certification centers, located in the metros. The trainees learn and earn for the next 18 months, staying in no-rent company dormitories, eating free food, and receiving an annual stipend of about 5,000 rupees a month (roughly $100) in the first year, which rises to 7,000 rupees a month ($142) in the second year. Trainees remit most of their stipends to their families, because the Taj Group pays their living costs. As a result, most work hard and display good values despite the temptations of the big city, and they want to build careers with the Taj Group. The company offers traineeships to those who exhibit potential and haven’t made any egregious errors or dropped out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One level up, the Taj Group recruits supervisors and junior managers from approximately half of the more than 100 hotel-management and catering institutes in India. It cultivates relationships with about 30 through a campus-connect program under which the Taj Group trains faculty and facilitates student visits. It maintains about 10 permanent relationships while other institutes rotate in and out of the program. Although the Taj Group administers a battery of tests to gauge candidates’ domain knowledge and to develop psychometric profiles, recruiters admit that they primarily assess the prospects’ sense of values and desire to contribute. What the Taj Group looks for in managers is integrity, along with the ability to work consistently and conscientiously, to always put guests first, to respond beyond the call of duty, and to work well under pressure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the company’s topmost echelons, the Taj Group signs up 50 or so management trainees every year from India’s second- and third-tier B-schools such as Infinity Business School, in Delhi, or Symbiosis Institute, in Pune, usually for functions such as marketing or sales. It doesn’t recruit from the premier institutions, as the Taj Group has found that MBA graduates from lower-tier B-schools want to build careers with a single company, tend to fit in better with a customer-centric culture, and aren’t driven solely by money. A hotelier must want, above all else, to make other people happy, and the Taj Group keeps that top of mind in its recruitment processes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Training Customer Ambassadors''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group has a long history of training and mentoring, which helps to sustain its customer centricity. The practice began in the 1960s, when CEO Ajit Kerkar—who personally interviewed every recruit, including cooks, bellhops, and wait staff, before employing them—mentored generations of employees. The effort has become more process-driven over time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most hotel chains train frontline employees for 12 months, on average, but the Taj Group insists on an 18-month program. Managers, too, go through 18 months of classroom and on-the-job operations training. For instance, trainee managers will spend a fortnight focusing on service in the Taj Group’s training restaurant and the next 15 days working hands-on in a hotel restaurant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group’s experience and research has shown that employees make 70% to 80% of their contacts with guests in an unsupervised environment. Training protocols therefore assume, first, that employees will usually have to deal with guests without supervision—that is, employees must know what to do and how to do it, whatever the circumstances, without needing to turn to a supervisor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One tool the company uses is a two-hour weekly debriefing session with every trainee, who must answer two questions: What did you learn this week? What did you see this week? The process forces trainee managers to absorb essential concepts in the classroom, try out newfound skills in live settings, and learn to negotiate the differences between them. This helps managers develop the ability to sense and respond on the fly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group also estimates that a 24-hour stay in a hotel results in between 40 and 45 guest-employee interactions, which it labels “moments of truth.” This leads to the second key assumption underlying its programs: It must train employees to manage those interactions so that each one creates a favorable impression on the guest. To ensure that result, the company imparts three kinds of skills: technical skills, so that employees master their jobs (for instance, wait staff must know foods, wines, how to serve, and so on); grooming, personality, and language skills, which are hygiene factors; and customer-handling skills, so that employees learn to listen to guests, understand their needs, and customize service or improvise to meet those needs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In a counterintuitive twist, the Taj Group insists that employees must act as the customer’s, not the company’s, ambassadors. Employees obviously represent the chain, but that logic could become counterproductive if they start watching out for the hotel’s interests, not the guests’, especially at moments of truth. Trainees are assured that the company’s leadership, right up to the CEO, will support any employee decision that puts guests front and center and that shows that employees did everything possible to delight them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Trainees are assured that the company’s leadership, right up to the CEO, will support any employee decision that puts guests front and center.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to senior executives, this shift in perspective changes the way employees respond to situations. Moreover, it alters the extent to which they act—and believe they can act—in order to please guests. A senior executive told us that when an irate guest swore he would never stay at the Taj Mumbai again because the air conditioner hadn’t worked all night, a trainee manager offered him breakfast on the house and provided complimentary transportation to the airport. She also ensured that someone from the next Taj property at which he was booked picked him up from the airport. Did the trainee spend a lot of the company’s money on a single guest? Yes. Did she have to ask for permission or justify her actions? No. In the Taj Group’s unwritten rule book, all that mattered was that the employee did her best to mollify an angry guest so that he would return to the Taj. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group’s training programs not only motivate employees, but they also create a favorable organizational culture. H.N. Shrinivas, the senior vice president of human resources for the Taj Group, notes: “If you empower employees to take decisions as agents of the customer, it energizes them and makes them feel in command.” That’s in part why the Taj Group has won Gallup’s Great Workplace Award in India for two years in a row. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Incumbent managers conduct all the training in the Taj Group, which uses few consultants. This allows the chain to impart not just technical skills but also the tacit knowledge, values, and elements of organizational culture that differentiate it from the competition. Every hotel has a training manager to coordinate the process, and given that Taj properties impart training only in the areas in which they excel, they vie with one another to become training grounds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Like all the other companies in the House of Tata, the Taj Group uses the Tata Leadership Practices framework, which lays out three sets of leadership competencies that managers must develop: leadership of results, business, and people. Every year 150 to 200 managers attend training sessions designed to address those competencies. The company thereafter tailors plans on the basis of individuals’ strengths and weaknesses, and it hires an external coach to support each manager on his or her leadership journey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Taj Group expects managers to lead by example. For instance, after a day of work, the general manager of every hotel is expected to be in the lobby in the evenings, to welcome guests. That might seem old-fashioned, but that’s the Taj tradition of hospitality. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A Recognition-as-Reward System''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Underpinning the Taj Group’s rewards system is the notion that happy employees lead to happy customers. One way of ensuring that outcome, the organization believes, is to show that it values the efforts of both frontline and heart-of-the house employees by thanking them personally. These expressions of gratitude, senior executives find, must come from immediate supervisors, who are central in determining how employees feel about the company. In addition, the timing of the recognition is usually more important than the reward itself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Using these ideas, in 2001 the Taj Group created a Special Thanks and Recognition System (STARS) that links customer delight to employee rewards. Employees accumulate points throughout the year in three domains: compliments from guests, compliments from colleagues, and their own suggestions. Crucially, at the end of each day, a STARS committee comprising each hotel’s general manager, HR manager, training manager, and the concerned department head review all the nominations and suggestions. The members of this group decide whether the compliments are evidence of exceptional performance and if the employee’s suggestions are good. Then they post their comments on the company’s intranet. If the committee doesn’t make a decision within 48 hours, the employee gets the points by default. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By accumulating points, Taj Group employees aspire to reach one of five performance levels: the managing director’s club; the COO’s club; and the platinum, gold, and silver levels. Departments honor workers who reach those last three levels with gift vouchers, STARS lapel pins, and STARS shields and trophies, whereas the hotel bestows the COO’s club awards. At an annual organization-wide celebration called the Taj Business Excellence Awards ceremony, employees who have made the managing director’s club get crystal trophies, gift vouchers, and certificates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to independent experts, the Taj Group’s service standards and customer-retention rates rose after it launched the STARS program, because employees felt that their contributions were valued. In fact, STARS won the Hermes Award in 2002 for the best human resource innovation in the global hospitality industry.The Taj Group’s hiring, training, and recognition systems have together created an extraordinary service culture, but you may still wonder if the response of the Taj Mumbai’s employees to 26/11 was unique. Perhaps. Perhaps not. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At about 9:30 AM on December 26, 2004, a tsunami rippled across the Indian Ocean, wreaking havoc on coastal populations from Indonesia to India, killing about 185,000 people. Among those affected was the island nation of the Maldives, where tidal waves devastated several resort hotels, including two belonging to the Taj Group: the Taj Exotica and the Taj Coral Reef. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Many guests were panic-stricken, but the Taj staff members remained calm and optimistic.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | As soon as the giant waves struck, guests say, Taj Group employees rushed to every room and escorted them to high ground. Women and children were sheltered in the island’s only two-story building. Many guests were panic-stricken, believing that more waves could follow, but staff members remained calm and optimistic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | No more waves arrived, but the first one had inundated kitchens and storerooms. A Taj Group team, led by the head chef, immediately set about salvaging food supplies, carrying cooking equipment to high ground, and preparing a hot meal. Housekeeping staff retrieved furniture from the lagoon, pumped water out of a restaurant, and restored a semblance of normalcy. Despite the trying circumstances, lunch was served by 1:00 PM. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The two Taj hotels continued to improvise for two more days until help arrived from India, and then they evacuated all the guests to Chennai in an aircraft that the Taj Group had chartered. There were no casualties and no panic, according to guests, some of whom were so thankful that they later volunteered to help rebuild the island nation. These Taj Group employees behaved like ordinary heroes, just as their colleagues at the Taj Mumbai would four years later. That, it appears, is indeed the Taj Way. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==The aborted wedding reception== | ||

| + | [https://www.livemint.com/Politics/VkV17dLYxfM9564Q9FTYzO/2611-attacks-anniversary-How-a-wedding-reception-turned-in.html Parizaad Khan, Nov 25, 2018 ''Livemint''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A former Mint staffer chronicles how she escaped the Taj Mahal hotel during the Mumbai terror attack. Now, a decade later, she looks back at the life-changing incident and says she has new learnings, more relevant to the times that we are living in | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The evening started rather innocuously at The Taj Mahal Palace and Tower’s Crystal Room, with a glass of musk melon juice. It was 9.30pm on 26 November and I was at Mumbai’s oldest five-star for a friend’s wedding reception. A friend and I had driven the car into the porch (a practice the management had discontinued for a while for security reasons) and passed through the doors with minimal security interference. We had just been asked to walk through a metal detector and my friend commented on how inadequate the security seemed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After we got to the Crystal Room in the Taj’s old wing, we met friends, picked up our first drink and nibbled on a few appetizers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We hadn’t been there 15 minutes when we heard sounds that we dismissed as construction work or fire crackers. When the boom boom went on and got nearer, it was apparent that they were neither. The staff had secured the doors of the room by now. We were standing in the middle of the room planning our next move, when a glass window that looked out into the main corridor shattered, and shots rang through the room. Instinctively we ducked and crouching, made our way to the service door, which led to an alcove. We crouched there for a minute, and then were ushered by staff through corridors, kitchens and other areas, till we reached the wood-panelled Chambers, an elite, by-membership-only club, whose patrons are the country’s top industrialists. We passed by executive grand chef Hemant Oberoi, who was surrounded by chefs and staff in white, but was gracious enough to smile at us. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once at the Chambers, we met other members of the wedding party, foreign guests living at the hotel, as well as patrons of the hotel’s restaurants such as Wasabi, Golden Dragon and Masala Craft. The staff kept ushering in new refugees, and soon the place was full—there were probably 300 people now. There was a large room leading to a terrace and a smaller room next to that. The Chambers also consist of a few corridors and waiting spaces, besides ladies and gents restrooms. The doors were locked and the staircase and elevator secured, we were told. By then we could not hear any more gunfire, and felt safer. People were bewildered and phone calls coming in confirmed that many places in the city had been similarly targeted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That’s when the Taj’s staff kicked in. Crates of Himalayan water bottles started to come in, followed by tins of potato chips. These were soon followed by chutney and cheese sandwiches and trays of canapйs. I spotted some patй and smoked salmon, but was too churned up to eat anything. Tray after tray of freshly made sandwiches kept coming through, followed by cans of aerated drinks. Soon, we had towels and crisp white bedsheets to wrap around us as blankets. Extra chairs were brought in. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They didn’t have to make sandwiches for 300 people or give out bedsheets—we would have managed just fine without them. They were in the same dangerous situation as us, but besides looking slightly strained, their training showed through. They listened patiently and replied courteously to even the silliest questions. Their grace lifted our spirits, even enough for people to make silly hostage jokes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A group of about 4-5 men were led in, with blood on their clothes. They had been outside the hotel, they explained, when two of their friends had been injured by the gunmen who were running past. They got help for their friends and then ran into the hotel for shelter. A red-eyed and petrified couple stood there as well. They had been dining at the Shamiana and were forced to run towards the pool and huddle in the surrounding bushes. Their 10-year-old son, who had gone to the restroom was still trapped there. The staff listened to their story and passed word around to get the boy out of there. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though we were frightened—by now we had heard a few blasts and rumours that the heritage dome had exploded and was on fire—we were not really in fear of our lives. The cops and special forces had come to the building, we were told, and everything would be cleaned up soon. At no point did we see the gunmen or were even aware of how many there were. People lay down on the floor and tried to get some sleep, while others paced. As usual, the ladies room was where all the gossip was shared. Two women were in the Harbour Bar, waiting for a table at Golden Dragon. As soon as they took a step into the bar, the shooting started behind them in the lobby, where they most probably passed the gunmen. Everyone ducked under tables and were slowly led through service entrances, to the Chambers. A foreign guest was in her room when she heard the shooting. She ran down with her friend and saw bodies in the lobby. A staffer led them to safety. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''It helped to not focus on the moments of terror and hate but on the acts of heroism we saw-''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | We soon heard whispers that we were going to be evacuated. That the Anti Terrorism Squad (ATS) had arrived, the Army had arrived. Then the news that the ATS chief and our top encounter specialist had been shot. But we were still getting out. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was probably about 3am when we gathered at the service door and were asked to be silent. It was a crush as everyone wanted to be the first to get out, but it was orderly and people didn’t panic. People were talking in whispers and there was much shushing for anyone who raised their voice. Two of my friends and I were probably in the fourth or fifth bunch of people to be evacuated. About 10 of us were led into a narrow corridor. A large group of people still waiting inside were pressed close to the door. An armed guard was present, as well as some other cops. But as soon as we went into the corridor, they moved away to clear another part of the hotel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | That was when it got chaotic. In the narrow, snaking corridor, where two people couldn’t walk comfortably side by side, we were fired at. We couldn’t tell where exactly the shots were from, but they were alarmingly close. We turned and ran back inside, keeping our heads down. There was almost a stampede-like situation, before the group pressed to the door behind us realized what was happening and moved back. People tripped and fell, but were pulled up and we ran back inside. We had no idea what happened to the rest who had been evacuated earlier. We ran to the larger room at the Chambers and sunk into chairs. After about half an hour, without any word from outside, we heard volleys of gunfire back and forth, from the corridor outside. Everyone flattened themselves on the ground, with their hands over their heads. We were snaked around the furniture and the floor was a tangle of bodies and limbs, each trying to make space for themselves, while doing the same for their companions on the ground. The lights were soon switched off and everyone was silent. We stayed that way till morning, with gunfire going back and forth, and even what sounded like grenade blasts coming from the corridor, probably just 30 feet from us. Soon those crisp sheets were being torn up to stanch wounds—a man had been shot in the arm and a woman had injured her leg. The dawn broke through the stained glass windows that led to the terrace. But still no word from anyone. We heard via cellphones, that the rest of the building had been evacuated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To everyone’s credit, there was no hysteria; a few people were crying softly but soon stopped. Everyone kept cool, even though, those hours before dawn were the bleakest. We seriously feared for our lives, and everyone was praying. Most softly, but some whispered chants of Jai Mata Di reached our ears. I was frightened, terrified actually, but was too busy praying through the gunfire to cry. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All through this ordeal, I had been exchanging text messages with friends and family. I must have exchanged over a hundred messages with my brother, who was frantic at home. Friends, colleagues, ex-colleagues and family members kept telling me they were praying, and that helped. They were passing on what they saw on the news—“the commandos have arrived, this squad has stormed the building, that one has now come; you’re sure to be rescued soon". But we weren’t, not just then. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It had been silent for a few hours after dawn. At about 8.30am, a commando, with a machine gun and a bulletproof vest rushed in. We lifted ourselves off the floor at his instructions, with our hands in the air. “Does anybody have any weapons?" After we all whispered no, we were asked to line up. Just then, some commotion caused us to panic—I cannot remember if it was more shots, but someone shouted get down, and we all dived to the floor (not an easy feat in a sari). “I want you all to stay calm. Listen to me, there is nothing to worry about. The first bullet will go through me, I’m leading you out," our commando said. We got back up and we stepped out into a corridor, which was strewn with broken glass and bullet shells. Crunching our way through that, I spotted a small restaurant or private dining room, which was in a shambles. We walked down a flight of stairs guarded by commandos and through corridors; in some there were pools of congealed blood. We made our way to the lobby and were led out into the sunshine on the porch, where we had given our car to the valet the night before. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But it wasn’t over yet. As a cop van and BEST bus pulled up and people started getting in, shots rang out at the vehicles from the hotel. Some of the gunmen were still inside. We all ran back to the lobby doors, but there was not much fear; the presence of the commandos and other personnel gave us courage. My friend and I were put into a BEST bus after 10 minutes. We were packed like sardines and everyone was crouched with their heads down. Some of us didn’t lift our heads till we got to Azad Maidan police station. The cops were quite comforting—they laid out plastic chairs for us, gave us water, and took our details, before we were free to leave. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''I didn’t leave that hotel untouched; but I realize now I gain nothing by shutting off my humanity.-''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Through all of this we were in touch with the bride and groom whose reception had been disrupted. They had not yet left their room in the old wing when the firing started. They laid low with the lights off, listening to the firing that was going on in the corridor outside their room. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the blasts blew open their room door. That was when they moved to the bathroom and locked themselves in there in the dark, with fire raging in the floors above them and gunfire everywhere. They were rescued at around 4am. We heard later that many police personnel and some of the hotel staff lost their lives. We’re probably alive because of them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dome of the Taj and the old wing is gutted. It was a much-loved majestic landmark for people like me who have grown up in Bombay. But just like the city, I doubt it will be down for too long. Now I’m just praying for the people still trapped in the Oberoi-Trident. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is a first person account, published in Mint on 29 November, 2008. At the time of the attack, Parizaad Khan was a features writer with Mint. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Transcripts of terrorists’ conversations with Pak handlers== | ||

| + | [https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/2611-mumbai-attacks-chilling-transcripts-reveal-how-terrorists-pak-handlers-guided-them/519644 Nov 26, 2019''Times Now News''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | On November 26, 2008, ten men arrived in Mumbai on an inflatable fishing boat. They then broke into pairs, before hailing cabs and travelling to prominent locations across the city including the Taj Mahal Hotel, the Trident Oberoi and Leopold Café. Four days later, when the siege ended, 166 people were dead, and one terrorist - Ajmal Kasab - had been apprehended. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Investigations that followed the incident revealed a series of chilling phone conversations the terrorists had with their handlers as they unleashed mayhem on the innocent Mumbai population. As tributes poured in on November 26, in remembrance of the victims of the terror attack that took place 11 years ago, we look at some select excerpts from the intercepted exchanges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Zabiuddin Ansari, one of the chief handlers, instructs a terrorist at Chabad House in Nariman Point to lie to the police and media,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ansari: Tell the boys to give the number of terrorists according to their fancy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: Yes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ansari: Don’t reveal your numbers. Don’t say 14 or 15. Say 4,5 or 6 only. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: Yes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ansari: And talk clearly because your programme will run on the media for hours. It is a matter of pride for us, the pride of the Mujahideen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''One of the controllers instructs the terrorists at the Taj Mahal Hotel to start a fire, but the terrorists are distracted by the hotel’s facilities,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: Walekhum salaam. How are you getting on? Have you started the fire yet? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: (Nervous laughter) No, we haven’t started it yet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: You must start the fire now. Nothing is going to happen till you start the fire. When people see the flames, they will start to be afraid. And throw some grenades, my brother. There’s no harm in throwing a few grenades. How hard can it be to throw a few grenades? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: (Excitedly) There are computers here with 30-inch screens! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: Computers? Haven’t you set them alight already? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: We’re just about to. You’ll be able to see the fire any minute now. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Another handler called “Brother Wasi” instructs a terrorist to kill hostages at the Chabad House (Jewish religious and cultural center),''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: I told you, every person you kill where you are, is worth 50 of the ones killed elsewhere. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''When calls to negotiate the release of hostages do not materialise,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: Listen up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: Yes sir. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: Just shoot them now. Get rid of them. You could come under fire at any time and you risk leaving them behind. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: (Stalling) Inshallah. Although it’s quiet at the moment here. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: No. Don’t wait any longer. You might never know when you come under attack. Just make sure you don’t get hit by a ricochet when you do it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A handler informs one of the terrorists at the Taj Mahal Hotel of the location of police officials,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: The way you have turned, you should be facing the sea. There, at the corner of the road, there is a building of civilian people. In reality that belongs to the Navy. It is given to the civilians. Over there, policemen are standing at two places. They have taken the position and, taking aim at you, they are firing at you, in the direction that you have gone. You would have to come from behind and fire at them. Do you understand? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: All right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A handler tells one of the terrorists at the Trident Oberoi that he cannot be captured at any cost,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: There cannot be the eventuality of arrest. You have to remember this. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: No. God willing, god willing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: My brother you have to be strong. Do not be afraid. God willing. If you are hit by a bullet, in that is your success. God is waiting for you. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: All right. God willing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A handler assures one of the terrorists at Nariman Point that no other terrorists have been arrested,''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: He was saying two brothers have surrendered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: No, they are talking nonsense. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Terrorist: Ji, | ||

| + | |||

| + | Controller: Surrendered?!!! He is talking rubbish! From yesterday till today no place has been cleared by them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===''The New York Times'' details the dossier=== | ||

| + | [https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/07/world/asia/07india.html Somini Sengupta, Jan 6, 2009 ''New York Times''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Dossier Gives Details of Mumbai Attacks - The New York Times | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Jan 6, 2009 - Don't be taken alive,” a caller said to a gunman in the Oberoi Hotel in the ... are outside,” came one instruction to the gunmen inside the Taj Mahal hotel. ... The last telephone transcript in the dossier was at 10:26 p.m. on Nov. | ||

| + | |||

| + | NEW DELHI The exchanges are chilling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The hostages are of use only as long as you do not come under fire,” a supervisor instructed gunmen by phone during the Mumbai attacks in November. He added: “If you are still threatened, then don’t saddle yourself with the burden of the hostages. Immediately kill them.” | ||

| + | A gunman replied, “Yes, we shall do accordingly, God willing.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | These are some of the grim details of the Mumbai attacks compiled by the Indian authorities and officially shared with the Pakistani government on Monday. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The compilation seems intended to achieve at least two objectives for India: demonstrate that the attackers were sent from Pakistan, and rally international support for India’s efforts to press Pakistan on its handling of terrorism suspects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To that end, the dossier, a copy of which was shown to The New York Times, includes previously undisclosed transcripts of telephone conversations, intercepted by Indian authorities, that the 10 gunmen had during their killing spree. They left 163 dead, all the while receiving instructions and pep talks from their handlers across the border. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dossier also includes photographs of materials found on the fishing trawler the gunmen took to Mumbai: a bottle of Mountain Dew soda packaged in Karachi, pistols bearing the markings of a gun manufacturer in Peshawar, Pakistani-made items like a matchbox, detergent powder and shaving cream. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Beyond that, the dossier chronicles India’s efforts in recent years to persuade Pakistan to investigate suspects involved in terrorist attacks in India and to close terrorist training camps inside Pakistani territory. In the final pages, India demands that Pakistan hand over “conspirators” to face trial in India and comply with its promise to stop terrorist groups from functioning inside its territory. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dossier was shown this week to diplomats from friendly nations; one described it as “comprehensive,” another as “convincing.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the dossier takes pains not to blame current or former officials in Pakistan’s army or spy agency, Indian officials have consistently hinted at their complicity, at least in training the commando-style fighters who carried out the attack. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On Tuesday, the Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh, upped the ante, but stopped short of naming any specific entities or individuals. “There is enough evidence to show that, given the sophistication and military precision of the attack, it must have had the support of some official agencies in Pakistan,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pakistan rejected the Indian allegation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Scoring points like this will only move us further away from focusing on the very real and present danger of regional and global terrorism,” Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s information minister, said in a statement, according to Reuters. “It is our firm resolve to ensure that nonstate actors do not use Pakistani soil to launch terrorist attacks anywhere in the world.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pakistan has said it is examining the information sent by India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dossier narrates a journey of zeal, foibles and careful planning, one whose blow-by-blow news coverage was followed by handlers, believed to be in Pakistan, and used to caution the gunmen about the movement of Indian security forces and to motivate them to keep fighting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Everything is being recorded by the media. Inflict the maximum damage. Keep fighting. Don’t be taken alive,” a caller said to a gunman in the Oberoi Hotel in the early hours of the three-day rampage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Throw one or two grenades at the Navy and police teams, which are outside,” came one instruction to the gunmen inside the Taj Mahal hotel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Keep two magazines and three grenades aside and expend the rest of your ammunition,” went another set of instructions to the attackers inside Nariman House, which housed an Orthodox Jewish center. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the Taj Mahal, the attackers were asked by their counselors whether they had set the hotel on fire; one attacker said he was preparing a mattress for that purpose. At the Oberoi, an attacker asked whether to spare women (“Kill them,” came the terse reply) and Muslims (he was told to release them and kill the rest). At Nariman House, they were told that India’s standing with a major ally, Israel, might be damaged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “If the hostages are killed, it will spoil relations between India and Israel,” one handler said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the investigation into the attack, the 10 gunmen boarded a small boat in Karachi at 8 a.m. on Nov. 22, sailed a short distance before boarding a bigger carrier believed to be owned by an important operative of a banned Pakistan-based terrorist group, Lashkar-e-Taiba. The next day, the 10 men took over an Indian fishing trawler, killed four crew members, and sailed 550 nautical miles along the Arabian Sea. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Each man carried a weapons pack: a Kalashnikov, a 9-millimeter pistol, ammunition, hand grenades and a bomb containing a military-grade explosive, steel ball bearings and a timer with instructions inscribed in Urdu. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By 4 p.m. on Nov. 26, the trawler approached the shores of Mumbai. The leader of the crew, identified by Indian investigators as Ismail Khan, 25, from a Pakistani town in the Northwest-Frontier Province, contacted his handlers. When darkness set in, the men killed the trawler’s captain and boarded a dinghy, with an engine that investigators said bore marks from a Lahore-based importing company. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They reached Mumbai about 8:30 p.m., and in five teams of two, set upon their targets: Chhatrapati Shiva ji Terminus, known as Victoria Terminus, the city’s busiest railway station; a tourist haunt called the Leopold Cafe; the Jewish center in Nariman House; and the Taj Mahal and Oberoi hotels. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They made one mistake, investigators said. They left behind Mr. Khan’s satellite phone; it was recovered by Indian investigators and its photograph was included in the dossier. A GPS device was also recovered from the trawler. | ||

| + | The last telephone transcript in the dossier was at 10:26 p.m. on Nov. 27, between a gunman inside Nariman House and his interlocutor. “Brother you have to fight,” the caller said. “This is a matter of the prestige of Islam.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the morning of Nov. 29, Indian forces had killed nine of the fighters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The sole survivor, Muhammad Ajmal Kasab, is in the custody of the Mumbai police. His interrogation turned up one of the most frightening details: he was part of a cadre of 32 would-be suicide bombers, later joined by three more men. Ten went to Mumbai. Six went to Indian-administered Kashmir, Mr. Kasab told his interrogators. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dossier says nothing about what happened to the remaining trainees. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Crime|M | ||

| + | MUMBAI ATTACKS, 26/ 11 2008]] | ||

| + | [[Category:History|M | ||

| + | MUMBAI ATTACKS, 26/ 11 2008]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|M | ||

| + | MUMBAI ATTACKS, 26/ 11 2008]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pakistan|M | ||

| + | MUMBAI ATTACKS, 26/ 11 2008]] | ||

=An analysis= | =An analysis= | ||

Revision as of 09:12, 28 June 2021

Contents |

In brief

From: November 26, 2017: The Times of India

From: November 26, 2017: The Times of India

India Today, December 29, 2008

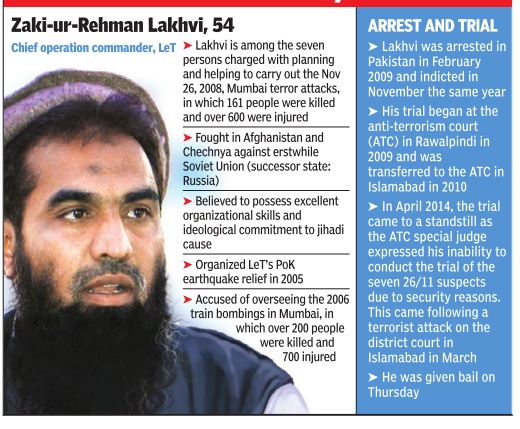

See graphics:

The Mumbai attacks, November 26-28, 2008- places, dates and deaths

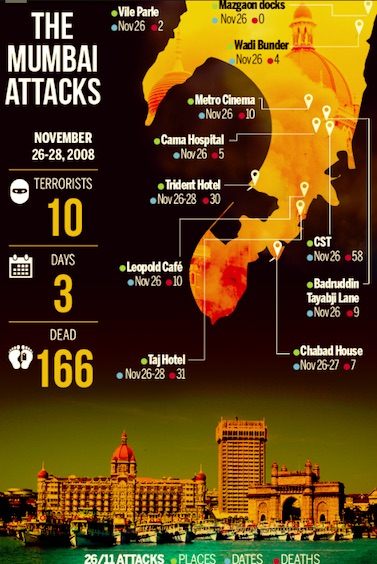

'The Mumbai attacks, November 26-28, 2008- The main accused

India’s 9/11

Mumbai attacked, 2008

The 59-hour-long televised tableau of terror that unfolded in Mumbai on November 26 and numbed the nation was the new benchmark for terror as well as for the in-built sloth in India’s intelligence and security setups. The audacious attack, simultaneously carried out at 11 places in India’s financial capital, by a group of 10 armed terrorists, came from the Arabian Sea. “Indian citizens are condemned to be the permanent victims of jihad and a political class which has no sense of the nation,” said India Today in its December 2008 issue.

The case since 2009

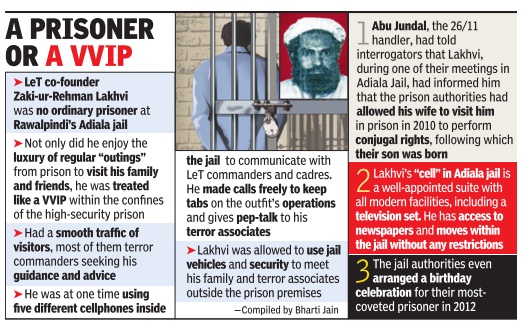

Omer Farooq Khan, Dec 19 2014

Lakhvi Gets Bail For 'Lack Of Evidence' A day after Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and the country's political leadership vowed to fight the last terrorist standing, a Rawalpindi anti-terrorism court on Thursday granted bail to Zaki-ur Rehman Lakhvi, the key handler in the 2611 Mumbai attacks case, causing outrage in India. Lakhvi, 54, and six others had filed bail applications on Wednesday in midst of a lawyers' strike called to condemn the Peshawar school massacre that left 148 people, including 132 children, dead.

Lakhvi's bail comes a day after India expressed full solidarity with Pakistan in the aftermath of the Peshawar massacre, and the court order led New Delhi to react strongly against the bail. The court said the charge-sheet against Lakhvi and other accused was flawed and lacking in evidence. The prosecutor said the government would appeal against the court's bail order. Sources said the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), which had provided solid evidence to the court about LeT's involvement in the Mumbai attacks, disagreed with the bail but had to accept the court order.

The court directed Lakhvi, a trusted lieutenant of Ja maat-ud-Dawa chief Hafiz Saeed, to pay surety bonds worth Rs 5,00,000 ($5,000). “We were not expecting this decision as we were still to produce a good number of witnesses in the case,“ said chief prosecutor Chaudhry Azhar. Operations commander of the banned Lashkar-e-Taiba, the parent organization of Jamaat-ud-Dawa, Zaki-ur Rehman Lakhvi is one of the seven accused of planning, financing and executing the 2611 Mumbai carnage that killed 166 people. Six other accused are Hammad Amin Sadiq, Shahid Jamil Riaz, Younas Anjum, Jamil Ahmed, Mazhar Iqbal and Abdul Majid.

He and many of his associates were arrested from LeT's headquarters in Muzaffarabad in December 2008 and the case against them registered in February 2009. Since then, the case had been moving at a snail's pace with almost negligible headway .

Following the confession of Ajmal Kasab, the lone fidayeen survivor of the Mumbai attack, naming Lakhvi as his trainer, Syed Zabiuddin Ansari alias Abu Jandal, an Indian national who was arrested in and deported from Saudi Arabia in June 2012, too confessed he was in the control room with Lakhvi in Karachi monitoring the Mumbai attacks. Pakistani-American jihadi David Headley too had confessed to Lakhvi's key role in the Mumbai attacks.

Earlier, the FIA, which had investigated the Mumbai attacks case, had told the court that those who killed over 166 people in Mumbai belonged to the LeT and had been trained in Pakistan.

Lakhvi's counsel Raja Rizwan Abbasi told agencies that the court had granted bail as “evidence against Lakhvi was deficient“.

He said the defence would soon file bail applications of the other six accused. The incamera hearing of the case was held at Adiala Jail Rawalpindi due to security concerns. The judge adjourned the hearing till January 7.

In February 2009 interior minister Rehman Malik had said Lakhvi was in custody and under investigation as the “foremost mastermind” behind the Mumbai attacks.

Ten key points

What happened on 26/11?: 10 key points, 26 Nov, 2016, The Times of India/ Agencies

On November 26, 2008, Mumbai fell victim to one of the worst terrorist attacks in Indian history. Its perpetrators, members of the terrorist group Lashkar-e-Taiba, terrorized Maximum City for three days, targeting some of its most best-known locations and killing up to 166 people.

On the eighth anniversary of the attacks, here's a short guide to the events that unfolded on November 26 and the days that followed.

1. A three-day onslaught

In a three-day onslaught that began on November 26, 2008, 10 terrorists targeted several high-profile locations in Mumbai, including the landmark Taj Hotel at the Gateway, the Oberoi Trident at Nariman Point, Leopold Café, and Chhatrapati Shiva ji Terminus - killing up to 166 people, and leaving 300 injured. Up to 26 foreign nationals were among those killed by the terrorists.

2. From Karachi to Mumbai

The terrorists, arrived in Mumbai on the night of November 26, after travelling from Karachi by sea. All of them, save one - Ajmal Kasab, - were eventually killed in counter-terror operations.

3. Kasab hanged

Kasab, captured alive, was sentenced to death by a special anti-terror court in May 2010, and hanged at the Yerawada central prison in Pune in November 2012.

4. The martyrs of 26/11

Up to 18 security personnel were martyred in the attack. Among them were Mumbai Anti-Terrorist squad chief Hemant Karkare, Army Major Sandeep Unnikrishnan, Mumbai's Additional Police Commissioner Ashok Kamte, Senior Police Inspector Vijay Salaskar, and assistant sub-inspector Tukaram Gopal Omble.

5. Omble's valour

It was Omble's supreme sacrifice that made the capture of Ajmal Kasab possible. On the night of November 26 near Girgaum Chowpatty, he grabbed the barrel of Kasab's assault rifle, and - when the terrorist began shooting him - didn't let go of him, providing his team-mates with the perfect cover and preventing Kasab from harming anyone else.

6. The 26/11 attacks case in Pakistan

Lashkar-e-Taiba operations commander Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi stands accused - along with six others - of abetment to murder, attempted murder, and planning and executing the Mumbai attack, in a case that has been drawn out for more than six years in Pakistan. Another accused, former LeT member Sufayan Zafar - who was arrested on charges that he financed the Mumbai attacks - was recently absolved by Pakistan's Federal Investigative Agency.

7. India suggests ways to expedite trial

India wrote to Pakistan in September to suggest ways in which the trial in the 26/11 terrorist attacks case could be expedited, Ministry of External Affairs Spokesperson Vikas Swarup said. The prosecution in the trial, on its part, said in October that India hadn't responded to Pakistan's request that it send 24 witnesses in the case to testify in court, and that the case couldn't move forward until India did so.

8. The case goes on

The seven people accused of planning and executing the Mumbai attacks - including Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi - in September challenged the legality of a Pakistani judicial commission which went to India in 2013 to probe the attacks. Lakhvi was released from prison on bail last year, while the other six accused are in Rawalpindi's Adaila Jail.

9. Hafiz Saeed's role

Hafiz Saeed, founder of the terrorist organisation Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and the chief of the Jamaat-ud-Dawa (or JuD, a charity organisation considered to be a cover for the LeT), is another key mastermind of the attack.

10. JuD banned in Pakistan; Saeed put under house arrest, then released

The United Nations Security Council banned the JuD after the Mumbai attacks. Pakistan, too, gave in to international pressure and banned the JuD, and placed Hafiz Saeed under house arrest for months, but ended up letting him go. He now lives as a free citizen in Lahore, and India's demands that he be brought to book have been met with the response that Pakistan doesn't have the evidence it needs to prosecute him.

Highlights

Oneindia | 26th Nov, 2015 11:12 AM

On Nov 26 2008 a group of 10 terrorists associated with Lashkar-e-Tayiba (LeT) attacked India's financial capital Mumbai. It left India, and the world, shocked by the audacity of the attack.

The terrorists who took part in the 2008 Mumbai attacks arrived by sea rout to reach their destination to create horror among people of Mumbai. They were highly trained and were preparing for this strike for quite a long time.

The 10 terrorists from Pakistan created havoc in Mumbai with more than 10 coordinated shooting and bombing attacks on hotels, a train station, a hospital and a Jewish community centre over three days.

Here are some facts you need to know about 26/11 attacks

1. Ten terrorists from Karachi took sea route to land in Mumbai in 2008.

2. The deadliest terror attacks carried out on Indian soil started on 26 November (Wednesday) and lasted until Saturday, 29 November 2008.

3. The multiple attacks and the counter -terrorist offensive lasted over 60 hours.

4. Attacks were carried out by terrorists at Railway station, Leopold Cafe, Taj Mahal Palace & Tower Hotel, Oberoi Trident Hotel, Metro Cinema, Cama and Albless Hospital and Nariman House.

5. The terrorists used automatic weapons and grenades in the attacks.

6. During the three-day assault on the city more than 160 people including foreign nationals were killed and 308 people injured in the deadliest attacks carried out on Indian soil.

7. Apart from attacks at various locations, two taxis were also exploded in the city the same evening by the use of time bombs.

8. Nine of the gunmen were killed during the attacks, one survived. Mohammed Ajmal Kasab, the lone surviving gunman, was executed in India in November 2012 in Yerwada jail, Pune.

9. National Security Guards (NSG) conducted 'Operation Black Tornado' to flush out the terrorists.

10. Hafiz Saeed, leader of Jama'at-ud-Da'wah (JuD) is said to be the alleged master mind behind the 26/11 Mumbai attacks. Hafiz Saeed who operated mainly from Pakistan planned and executed the entire 26/11 Mumbai attack plan.

Source: www.oneindia.com

A timeline of events

The Hindu, September 30, 2015

11 July, 2006

Seven RDX bombs rip the first class compartments of Mumbai local trains between Churchgate and Bhayander station in a span of 11 minutes. 189 dead, around 800 injured

21 July, 2006

Police arrest three persons in connection with the blasts.

30 November, 2006

ATS files charge sheet, 13 arrested accused and 15 absconding accused charged under MCOCA

21 June, 2007

7/11 accused move Supreme Court challenging the constitutional validity of MCOCA. In February 2008, Supreme Court ordered a stay on the trial.

23 September, 2008

Mumbai Crime Branch arrests five IM operatives. Crime branch probe shows IM carried out the bombings, contradicting ATS that Pakistani nationals also planted bombs.

13 February, 2010

Young lawyer Shahid Azmi, who defended some of the accused in 7/11 case, shot dead in his central Mumbai office.

23 April, 2010

Stay on trial vacated, examination of witnesses resume

23 June, 2010

Media barred from entering court conducting trial

30 August, 2013

Yasin Bhatkal, co-founder of IM, arrested at Indo-Nepal border. Yasin claims the 2006 bombings were done by IM in retaliation to the 2002 riots, raising questions about arrest of 13 accused by ATS

20 August, 2014

7/11 trial concludes and court reserves judgment

11 September, 2015

MCOCA court convicts 12 of the 13 arrested accused in the case.

30 September, 2015

MCOCA court sentences five convicts to death. Seven get life imprisonment.

How the terror attack unfolded

November 26, 2018: The Times of India

It's been a decade since the deadly terror attacks took place in Mumbai, claiming the lives of as many as 165 and leaving over 300 injured. Ten years on, the feelings of anger, helplessness and deep sense of loss and pain still exists among those who were witness to this act of horror. Here's a look at how this gruesome attack unfolded.

Policemen were afraid, let Kasab flee railway station

The photojournalist who captured the chilling image of 26/11 Mumbai attack terrorist Ajmal Kasab at the Chhatrapati Shiva-ji Maharaj Terminus, says police let Kasab and his accomplice flee from the railway station.

On November 26, 2008, Sebastian D'Souza ran out from his office next to the train station armed with nothing more than his Nikon camera and lenses, after hearing the gunfire.

The photo and testimony of 'Saby', as he is known in media circles, was to play a crucial role in the 26/11 trial, which led to Kasab's hanging in 2012.

"Had policemen posted near the railway station killed Kasab and the other terrorist inside the station, so many lives could have been saved," Saby told .

In one of the most horrific terrorist attacks on the soil of India, 166 people were killed and over 300 were injured when ten heavily-armed terrorists from Pakistan ran a rampage in Mumbai 10 years ago.

"There were two police battalions present near the station, but did nothing," said Saby, who retired in 2012 and settled in Goa.

Saby, 67, won the World Press Photo award for the close-up photograph of Kasab, holding an AK-47.

He took the photos using a telephoto lens on his Nikon camera, while hiding inside a train carriage.

"I ran into the first carriage of one of the trains on the platform to try and get a shot, but as I could not get a good angle, moved to the second carriage and waited for the terrorists to walk by. I briefly had time to take a couple of frames. I think they saw me taking photographs, but didn't seem to care," he said.

Having given up photography after retirement, Saby now keep himself busy with carpentry and paintings.

"I don't want to remember what I did that (November 26) night," he said, terming the sequence of events as an 'old film' which he wants to erase from his memory.

Kasab was grinning while firing

Ten years after the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks, terrorist Mohammad Ajmal Kasab's grin is still etched in Vishnu Zende's memory.

The railway announcer's presence of mind saved the lives of hundreds of commuters at the Chhatrapati Shiva-ji Maharaj Terminus here that fateful night.

"I remember the evil grin on Kasab's face. Armed with an assault rifle, he was walking towards the suburban platform," he said.

Zende, 47, vividly recalls Kasab "grinning and abusing people" while spraying bullets from his assault rifle as the biggest ever terror attack on India unfolded on November 26, 2008.

Now working as a guard in the Central Railway, Zende says he is unable to forget the terror attack and the "barbaric" way in which the terrorist went about slaying people.

Of the 166 killed in the 26/11 attack, 52 died at the railway station. As many as 108 were injured in the firing at the station.

"While firing indiscriminately, Kasab also waved his hand at us, signalling that we (railway staff) come out of the control room," Zende said.

The terrorist was mercilessly firing at people who were running to save their lives, he said. "When Kasab found nobody to kill at the platform, he also fired at a dog, he added.

"After hearing a loud sound on the long-distance train platform, I first thought it was a blast and started announcing that people should not go near the blast site. I also requested railway police to rush to the site," he said.

As soon as Zende made the announcement, he saw Kasab and a second terrorist coming towards the suburban trains' platform. "That was the moment I realised it was a terror arrack," he said.

"I had to alert commuters about the terrorists and started announcing about the attack. I told people to vacate the station immediately," he said.

Zende asked passengers to leave the station from the rear end of Platform No. 1 as he felt it was a relatively safe place at that time.

The railway staffer who also deposed as a witness in the 26/11 case, said, "I saw two faces of Kasab: one with the evil grin during the firing and a dispassionate one, bereft on any emotion, inside the courtroom".

Police was unaware of Chabad House

Among the iconic targets of the 26/11 terrorist attacks in Mumbai — Taj Mahal Hotel, CST and Leopold Cafe — there was one that the local police did not even know existed. When the ministry of external affairs, alerted by Israelis of a terror situation unfolding on November 26, 2008, against Jews residing in Colaba, first reached out to Mumbai Police, the latter’s initial response was that there wasn’t any Jewish centre in the area.

Mumbai Police was then grappling with the sheer magnitude of the multi-target attacks, with all its resources on the ground. The call for help by an MEA official, which came amid a sea of rescue calls from affected citizens and VIPs, did not quite set alarm bells ringing. With the local police station and even officials of the special branch’s foreigners division unaware of a Chabad House in Nariman House at Colaba, all the police promised was to check and revert.

Meanwhile, an Israeli diplomat had reached Colaba police station to report the attack on Jewish settlement in the area. The control room, which first got the message of firing in Colaba Wadi at 2217 hours, had no idea it was taking place at Nariman House. A senior special branch officer present at Colaba police station decided to head to Taj instead. Central intelligence agencies meanwhile also asked Mumbai police to check on the attack on Jews reported by Israeli embassy through MEA.

Finally, it was ACP Issaq Ibrahim Bagwan who decided to move from Leopold Cafe to Colaba Market upon hearing a loud explosion from that side. Even he could not locate the target building since not many in the locality knew the significance of Nariman House. It was only after he reached the spot that he learnt that Jews living there were under fire and in a hostage situation. He called for reinforcements, cordoned off the area and got people vacated from surrounding buildings.

The policemen started shooting at terrorists present in Nariman House from nearby buildings. On the morning of November 27, Moshe, the toddler child of the rabbi held hostage there, and his nanny Sandra Samuels came out. The gunfight between Mumbai police and terrorists went on till NSG came in on November 27 afternoon. Rabbi Gavriel Holtzberg and his pregnant wife Rivka were among the five Israeli hostages killed.

Interestingly, three intelligence alerts were shared with Mumbai police before 26/11 about possible attacks on Jewish targets. However, Nariman House was not identified as a target. As per Ram Pradhan committee which probed lapses behind 26/11, the threat could have been better handled but “none in Colaba police station or for that matter SB (special branch) knew about the existence of a Jewish settlement in Nariman House”.

After the 26/11 attacks, the government got Israeli authorities to share a complete list of Chabad Houses and Jewish centres across India. Requisite security arrangements were put in place.

The Taj Mahal Hotel: The happenings =

In the upcoming drama Hotel Mumbai (releasing November 29), Anupam Kher plays Hemant Oberoi, head chef of the Taj Mahal Palace & Towers, whose leadership skills are tested after the hotel is attacked on November 26, 2008. The film shows how Oberoi and his staff kept over a hundred guests safe in the exclusive Chambers lounge.

That night, head chef Hemant Oberoi would go on to lose seven of his staff, all of whom were shot in the kitchen. Oberoi spoke to IndiaToday.in on the 11th anniversary of the tragedy that changed Mumbai forever about what the sacrifices meant.

"You will remember the colleagues who laid down their lives and appreciate what they have done for the company," said Oberoi, who returned to his workplace on November 29, 2008, a few hours after the siege ended.

"If I had not moved on, my team wouldn't have. If they would see their leader shattered and broken, they would have given up," said Oberoi.

Oberoi was in the hotel - shuttling between the Chambers lounge and his office, only a few steps away - until November 27 morning, when he left along with 17 of his staff members. But this was only after at least 150 guests were rescued, before 3.45 am.

Oberoi could have left much earlier if he wanted to. Merryweather Road, he said, was only 20 seconds away. "We went out three times to call the cops to protect us and thereby help us take out the guests," he said. "But they didn't have orders."

Oberoi says he couldn't have done it without the support of his staff which included Aziz, an employee on dialysis, who refused to leave without him. "We lost more staff than guests," added Oberoi.

Remembering the scene on November 29 that year, Oberoi said that there was no electricity but the brutality of the attack was evident all over. "There were blood stains, mobiles and shoes were lying around," he said. "I have seen Wasabi counter smouldering."

Oberoi, who worked with the Taj group for 42 years until he left in 2016, currently runs his own restaurant in Mumbai. He is almost done with his book, My Spice Journey, which chronicles his 45-year-long culinary career. At least eight of the 150 odd pages, he said, are on the 26/11 attacks.

Ask him of how he held it together in such a crisis, his reply is, "We have become so selfish that we want to save our lives and not others. I strongly believe that karma comes back to you.”

Head chef Hemant Oberoi’s recollections

The ordinary heroes of the Taj

Rohit Deshpande and Anjali Raina Dec 2011 Harvard Business Review

On November 26, 2008, Harish Manwani, chairman, and Nitin Paranjpe, CEO, of Hindustan Unilever hosted a dinner at the Taj Mahal Palace hotel in Mumbai (Taj Mumbai, for short). Unilever’s directors, senior executives, and their spouses were bidding farewell to Patrick Cescau, the CEO, and welcoming Paul Polman, the CEO-elect. About 35 Taj Mumbai employees, led by a 24-year-old banquet manager, Mallika Jagad, were assigned to manage the event in a second-floor banquet room. Around 9:30, as they served the main course, they heard what they thought were fireworks at a nearby wedding. In reality, these were the first gunshots from terrorists who were storming the Taj.

The staff quickly realized something was wrong. Jagad had the doors locked and the lights turned off. She asked everyone to lie down quietly under tables and refrain from using cell phones. She insisted that husbands and wives separate to reduce the risk to families. The group stayed there all night, listening to the terrorists rampaging through the hotel, hurling grenades, firing automatic weapons, and tearing the place apart. The Taj staff kept calm, according to the guests, and constantly went around offering water and asking people if they needed anything else. Early the next morning, a fire started in the hallway outside, forcing the group to try to climb out the windows. A fire crew spotted them and, with its ladders, helped the trapped people escape quickly. The staff evacuated the guests first, and no casualties resulted. “It was my responsibility….I may have been the youngest person in the room, but I was still doing my job,” Jagad later told one of us.Elsewhere in the hotel, the upscale Japanese restaurant Wasabi by Morimoto was busy at 9:30 PM. A warning call from a hotel operator alerted the staff that terrorists had entered the building and were heading toward the restaurant. Forty-eight-year-old Thomas Varghese, the senior waiter at Wasabi, immediately instructed his 50-odd guests to crouch under tables, and he directed employees to form a human cordon around them. Four hours later, security men asked Varghese if he could get the guests out of the hotel. He decided to use a spiral staircase near the restaurant to evacuate the customers first and then the hotel staff. The 30-year Taj veteran insisted that he would be the last man to leave, but he never did get out. The terrorists gunned him down as he reached the bottom of the staircase.

When Karambir Singh Kang, the Taj Mumbai’s general manager, heard about the attacks, he immediately left the conference he was attending at another Taj property. He took charge at the Taj Mumbai the moment he arrived, supervising the evacuation of guests and coordinating the efforts of firefighters amid the chaos. His wife and two young children were in a sixth-floor suite, where the general manager traditionally lives. Kang thought they would be safe, but when he realized that the terrorists were on the upper floors, he tried to get to his family. It was impossible. By midnight the sixth floor was in flames, and there was no hope of anyone’s surviving. Kang led the rescue efforts until noon the next day. Only then did he call his parents to tell them that the terrorists had killed his wife and children. His father, a retired general, told him, “Son, do your duty. Do not desert your post.” Kang replied, “If it [the hotel] goes down, I will be the last man out.”

Three years ago, when armed terrorists attacked a dozen locations in Mumbai—including two luxury hotels, a hospital, the railway station, a restaurant, and a Jewish center—they killed as many as 159 people, both Indians and foreigners, and gravely wounded more than 200. The assault, known as 26/11, scarred the nation’s psyche by exposing the country’s vulnerability to terrorism, although India is no stranger to it. The Taj Mumbai’s burning domes and spires, which stayed ablaze for two days and three nights, will forever symbolize the tragic events of 26/11.

During the onslaught on the Taj Mumbai, 31 people died and 28 were hurt, but the hotel received only praise the day after. Its guests were overwhelmed by employees’ dedication to duty, their desire to protect guests without regard to personal safety, and their quick thinking. Restaurant and banquet staff rushed people to safe locations such as kitchens and basements. Telephone operators stayed at their posts, alerting guests to lock doors and not step out. Kitchen staff formed human shields to protect guests during evacuation attempts. As many as 11 Taj Mumbai employees—a third of the hotel’s casualties—laid down their lives while helping between 1,200 and 1,500 guests escape.