Mata Hari

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

‘Hindu’ dance

Malini Nair, When Mata Hari’s Hindu dance captivated Europe, February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: Malini Nair, When Mata Hari’s Hindu dance captivated Europe, February 21, 2020: The Times of India

New anthology rewinds to a time when a stereotypical vision of India was being celebrated on the Western cultural circuit

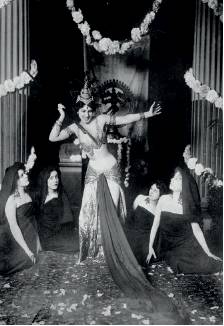

In a gauzy, barely-there costume, her face lit by a dazzling grin, Mata Hari appears to be playfully taking a stab at someone prone on the floor of Musee Guimet in Paris with a staff while a stoic Nataraja looks on. This was Mata Hari’s ‘Brahmanic Dance’ and it was anything but.

Even strip-tease passed for spiritual in the early 1900s when everything Indian was mystical and magical for a war-ravaged Europe. Dutch dancerturned-spy Mata Hari, who claimed to be a devadasi’s daughter, was not the only one to light up Europe’s theatres in the modernist years with a wild mishmash of choreographic effects that passed off as ‘Hindu/Hindoue/Hindou dance’, a selective synonym for ‘Indian’. There is Olive Craddock ‘Roshanara’ sari-clad, all bindi and bangles, in ‘Incense Dance’ (1913) which very likely imitated the dhunuchi of Bengal.

At a time when religious identity is being furiously debated in India, the latest Marg anthology of essays, A Mediated Magic: The Indian Presence In Modernism 1880-1930, presents an insight into the clichés about the great/wise/ancient land that became the rage in the avant garde cultural and intellectual circuits of Europe.

These fantastical typecasts of an otherworldly land were a salve for a continent grappling with the horrors of war and the dehumanising effect of industrialisation, says art scholar Naman Ahuja, co-editor of the book. “India as the land of ancient wisdom, religious and spiritual discourse, located in forests, populated by yogis, gurus, valorous aryans and destitutes with no more want than the upholding of their tradition — this was the typecast that was cherry-picked for the arts in Europe in these 50 years, a period of discovery and experimentation,” says Ahuja. “But it was a stereotype Indians didn’t let go of. It is this same reduction we see around us today when we think in terms of religious identity — we are now this Hindu of the caricature.”

The artists behind these Indian works — dance, music and theatre — were not uninformed. They were enlightened, widely-travelled, often socialists deeply concerned about India’s subjugation by the empire and critical of colonialism and racism. Many of them were performing travelogues of their own impressions while travelling in India, drawing from impressions of streets, kothas, markets and temples, points out Ahuja. German theatre director and manager Carl Hagemann, who described Tanjore’s temple dances as the most “pure and refined” art in the world, staged classic Sanskrit play Vasantasena in Mannheim in 1915 drawing on his own memories of the Indian landscape, scenery, architecture, dance and music. Again, these were interpretations of his impressions, not strong on authenticity, says writer Peter Max.

There was Russian ballet legend Vaslav Nijinsky playing the blue god (Shiva/Krishna) in the ‘Hindu ballet’ Le Dieu Bleu (1915). Here again, was a ghoulash of ‘Hindu’ myths — a woman is punished for seducing a priest, both chained to a cliff and attacked by monsters from the sea which are fought off by a flute-playing god and lotus goddess. “Mysticism, mystery and horror go no further,” dance critic Cyril Beaumont is cited as having said of the performance.

The first close look Europe had at an Indian dance on home turf, according to dance scholar Jane Pritchard, was when five temple dancers from Pondicherry arrived in Europe in 1838 and performed in the theatres of London and Paris. ‘Bayaderes (dancing girls) of Pondicherry’, as they were advertised, had everyone agog with their ‘rapid’ movements, “prodigious winks” and “outlandish” costumes.

“This was certainly not the first time that the West was studying India: in the 17th century, Rembrandt was already doing work inspired by Mughal art, by early 18th century, chairs in Sanskrit had been established in universities, there were many translations of Sanskrit works in English and European languages,” says Ahuja. “The west was looking for ways to comprehend India through the arts.”

But there was one problem with this ‘pernicious typecasting’, as Ahuja describes it — it was purely Hindu: “It left out the Islamic culture except in the depiction of opulence and decorativeness. No mention was made of the great advancements in philosophy or science in the Sultanate period or that of the Mughals.”