Migration: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

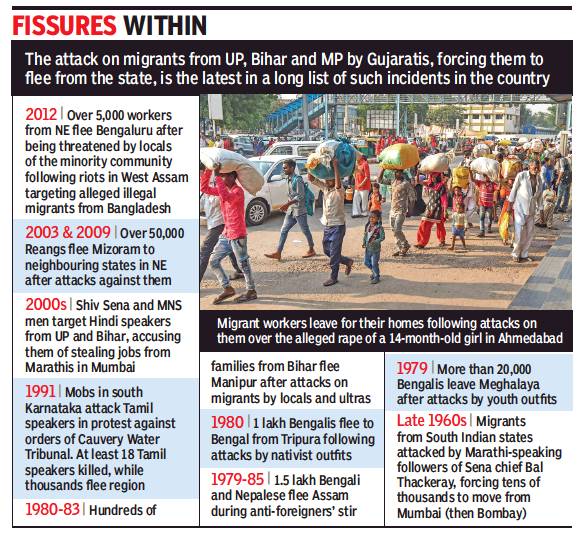

Attacks on migrants, normally workers

1960s-2018 (brief history)

From: October 9, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

1960s-2018: Attacks on migrants, normally workers, a brief history

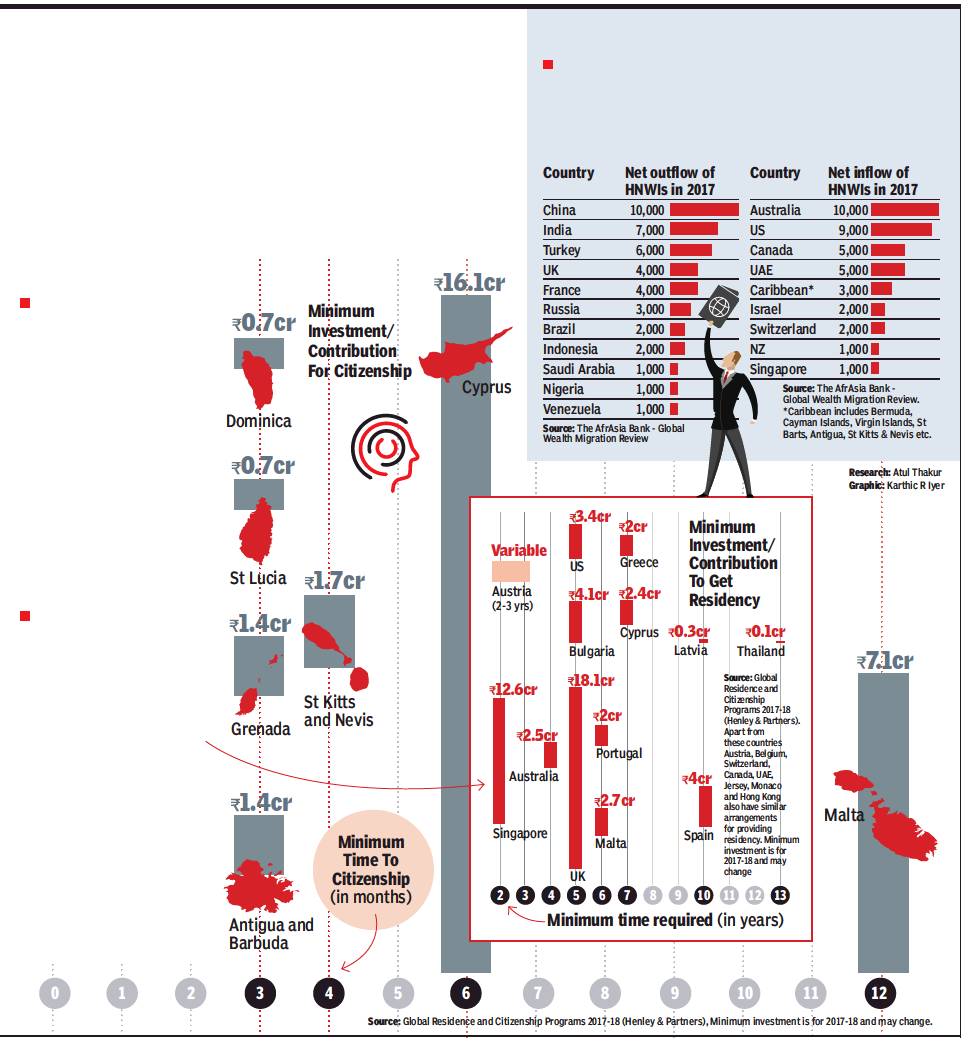

HNW individuals’ migration

How The Rich Buy New Nationalities; 2017 figures

How The Rich Buy A New Nationality, July 30, 2018: The Times of India

ii) THE countries that they migrate to.

From: How The Rich Buy A New Nationality, July 30, 2018: The Times of India

Fugitive Mehul Choksi bought Antiguan citizenship, and his new passport allows him visa-free entry to over 130 countries. TOI takes a look at how the rich can buy their way to new citizenship and residency

Can citizenship be acquired by investing?

Acquiring citizenship need not be a long-drawn process. Not all nations need you to prove years of residency. Many countries offer the wealthy citizenship-by-investment programmes. This method of granting citizenship was seen as controversial when Caribbean island St Kitts and Nevis pioneered the idea in 1984. But today many countries have followed suit to offer citizenship to well-heeled individuals who donate a fixed amount to the government of their new home or invest over a certain level.

Can permanent residency be acquired by investing?

Many countries that don’t provide citizenship but grant residency to the wealthy if they invest above a certain amount in the local economy. Residency provides unlimited stay and rights enjoyed by locals. These may include benefits like healthcare coverage and the right to work or study. Such residents cannot vote and are not issued passports of their new home nation. Indians, for instance, can apply for Tier 1 (Investor) visa of UK if they are willing to invest GBP 2 million (INR 18.1 cr). Similarly, the process for a US Green Card can be expedited for an individual who invests USD 1 million (or USD 500,000 in rural areas with few jobs) and creates at least 10 new full-time jobs.

Where are the super-rich going and which countries are the biggest losers?

South Africa-based New World Wealth, a global market research group that specialises in wealth statistics, found China followed by India witnessed the highest migration of high net worth individuals (HNWIs) — people with net assets of US$1 million (Rs 6.9cr) or more. The largest recipient of these super rich migrants are Australia, US and Canada.

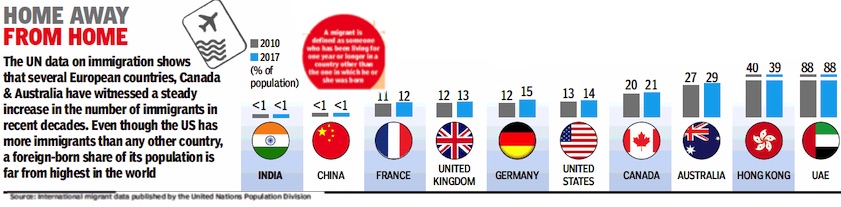

Immigration (into India)

2010, 2017: Migrants in India

From: February 5, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

2010, 2017: Immigrants living in India, China and major countries'

Internal migration

40% Indians migrants; mainly for marriage

Subodh Varma, 4 of 10 Indians migrants, most move for marriage, Dec 2, 2016: The Times of India

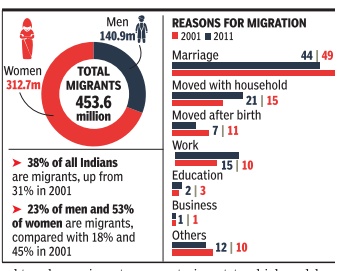

Nearly two out of five Indians -some 454 mil lion in all -are migrants, having left their place of residence and settled down somewhere else, according to fresh Census 2011 data on migration released on Thursday . Between 2001 and 2011, 139 million Indians migrated within the country . The vast majority of migrants, 69%, are women moving out of their parental homes to stay with their husbands in their native homes, or perhaps migrate with them elsewhere.

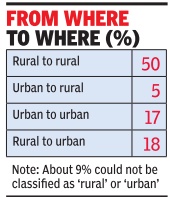

Half of this massive movement of humanity is taking place within rural areas -rural-to-rural migration.Rural-to-urban migration makes up about 18% while urban-to-urban is another 17%. In 2001, the share of ru ral-to-urban migrants was about 17%, indicating that there has not been a big shift in the percentage of people moving from villages to cities during the 2001-2011decade over the 1991-2001decade.

This complements the earlier data given by the census that the urban growth ra te is not too high and has slackened in many cities.

Among the reasons cited for migration by those surveyed, about 10% moved in search of employment during the decade ending 2011, down from 15% in 2001. This is counterintuiti ve, considering the po pular belief that mig ration is primarily driven by work.The share of those moving to pursue education makes up only 2% of migrants, down from 3% recorded in the 2001 census.

Marria ge remains the biggest cause for migration, accounting for 49%, up from 44% in 2001. The census questionnaire includes a reason de signated as “moved after birth“, which is mainly children being born in a pla ce -the mothers' village or a nearby town with hospital -and then moving back home to the parental ho use. This share has in 7% creased from in 2001 to 11%More in 2011.

than a fifth of all migrants had said in 2001 that the reason for migrating was that their fa mily was moving. They wo uld be dependents, both yo ung and old. This share has declined to 15% in 2011.

Hindi, Bengali, Odia speakers surge in South India/ 2011

Rema Nagarajan, June 28, 2018: The Times of India

Migration of non- southerners to south India.

From: Rema Nagarajan, June 28, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

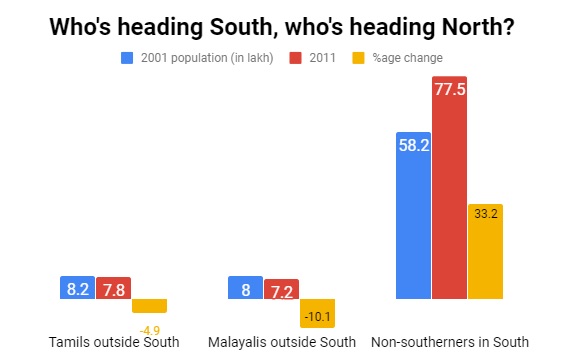

Just-released data from the 2011 census on mother tongues seems to indicate a reverse migration trend from earlier decades

Maharashtra, once a favoured destination for south Indians, mostly because of Mumbai, witnessed a decline in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam speakers

Tamil and speaking populations are falling across most states in north India even as and Kerala are seeing a huge jump in the number of Hindi, Bengali, Assamese and Odia speakers. Just-released data from the 2011 census on mother tongues seems to indicate a reverse migration trend from earlier decades when people from the two southern states migrated in large numbers to the north.

Instead, a large number of people from the two states are now migrating within the south, with Karnataka seeing a significant influx. Delhi saw a fall in numbers of both Tamil and Malyali speakers between the 2001 and 2011 censuses.

Maharashtra, once a favoured destination for south Indians, mostly because of Mumbai, witnessed a decline in Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam speakers. In the north, the highest growth in Malayali population between the 2001 and 2011 censuses was in Uttar Pradesh, perhaps because of Noida, while that of the Tamilian population was in Haryana, which might be because of Gurgaon.

But the absolute numbers involved are small compared with the migration of Tamilians and Malayalis within south India. While Tamil Nadu and Kerala saw the highest growth in Hindi speakers among all states, all of south India is witnessing a steady increase, with the highest absolute number of Hindi speakers in the region being in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

Kerala also saw the highest growth in Assamese and Bengalis even if the absolute numbers were not as high as in Maharashtra or Karnataka. The number of Nepali speakers too is growing fast in the south.In both cases, there is a growth of about 24% in populations speaking the respective languages.

Talent from north heads south

Recruitment agencies are facing a new challenge: While there are more job opportunities in the south thanks to a surge in startups, e-commerce and retail firms, the talent is in the north.

The south accounts for close to 40% of Randstad India’s recruitment for its clients, followed by the west at 28%, north at 25% and the east at 7%. For TeamLease Services, 40% of overall job positions are for the south. The figure would touch 70% if south and west are combined. Rituparna Chakraborty, co-founder, TeamLease Services, said: “People follow jobs and move where there is surplus demand for talent. At this point, that’s from north to south.”

Tally Solutions, a Bengaluru-based company that offers business management software solutions, has been recruiting from north India. Kankana Barua, chief people officer at Tally Solutions, said: “Companies facing a crunch in talent above mid-levels are looking for talent across India, especially from the north.”

The old reluctance to move to a city with a different language and cuisine is also eroding. Barua said that if a company provides good growth opportunities, people are ready to relocate. The influx of people from different regions to Hyderabad, Bengaluru and Chennai is creating cultural diversity. “I now see people conversing in Hindi in Chennai, for instance,” said Barua.

3 South IT hubs account for 60% of workforce

The south is home to three of India’s seven largest urban centres and accounts for more than half the total jobs created in the formal sector. The emergence of the IT industry as the single largest employer of graduates has played a significant role.

The three southern IT hubs of Chennai, Hyderabad and Bangalore account for more than 60% of the workforce employed by the sector, as per industry estimates. Chennai and Hyderabad are hubs for manufacturing and infrastructure too.

Paul Dupuis, MD and CEO, Randstad India, said: “The south will continue to lead the way in job creation, specifically in IT and related roles, given the headstart the region has in terms of the number of companies, presence of a qualified talent pool, quality educational institutions, and relative proximity of the three major urban centres.”

Naresh Rajendran, HR head, Grundfos India, which is headquartered in Chennai, said the company does not find it hard to hire talent willing to move to the south. He added that there is a trend of knowledge and blue-collar talent moving from other regions to the south, for IT, automotive, retail, e-commerce and infrastructure jobs.

2011-16

NEW DELHI: The Covid-19 pandemic may have brought the vulnerability of migrant workers into focus but data show more and more people have been moving from their native villages in search of work opportunities to other states over the decades. The magnitude of inter-state migration in India accelerated from five to six million annually between 2001-11 to nine million annually between 2011-16. Urban population in India grew from 286.1 million in 2001 to 377.1 million in 2011 which constitutes 31.14% of the total population residing in 53 urban agglomerations with more than a million people. Nearly 14% of this urban population was estimated to be living below the poverty line in 2011-12 with 65.5 million living in slums. India’s urban population is expected to rise to around 606 million by 2030. These figures are part of a comprehensive voluntary national review report on a wide range of sectors and progress made presented by Niti Aayog at the United Nations High-level Political Forum (HLPF) on sustainable development.

The report, Decade of Action: Taking SDGs from Global to Local, emphasises how India is focussing on making the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) monitoring and implementation more localised for better results. It maps India’s progress, challenges and the way forward on various SDG goals ranging from no poverty, zero hunger, good health and gender equality to sanitation, sustainable cities and reducing inequalities.

In the backdrop of the pandemic, Niti Aayog, vice chairman, Dr Rajiv Kumar, asserted that “the role of international cooperation is more critical than ever before.”

Despite the pressure on cities, the report says “migration can, in fact, be turned into a strong economic opportunity by overcoming bottlenecks such as migrants’ lack of access to healthcare, social entitlements, education for children, lack of improvement in skill profile and employability”.

A significant proportion of migrants and the poor in cities are employed in the informal economy which makes them vulnerable, especially in times such as the Covid-19 crisis. The report says that to mitigate the impact on various sectors including migrants both the central government and the states have announced an economic relief package with both short term and long term measures.

The report cites the importance of schemes like “One Nation, One Ration Card” for enabling access to subsidised foodgrains across the country, irrespective of the place of origin of migrants. It highlights the need for a database on migration and labour mobility to keep a tab on the current situation and take corrective measures.

Stakeholders feel labour welfare legislations which focus on safeguarding the livelihoods of those in the informal economy, require renewed impetus in urban centres.

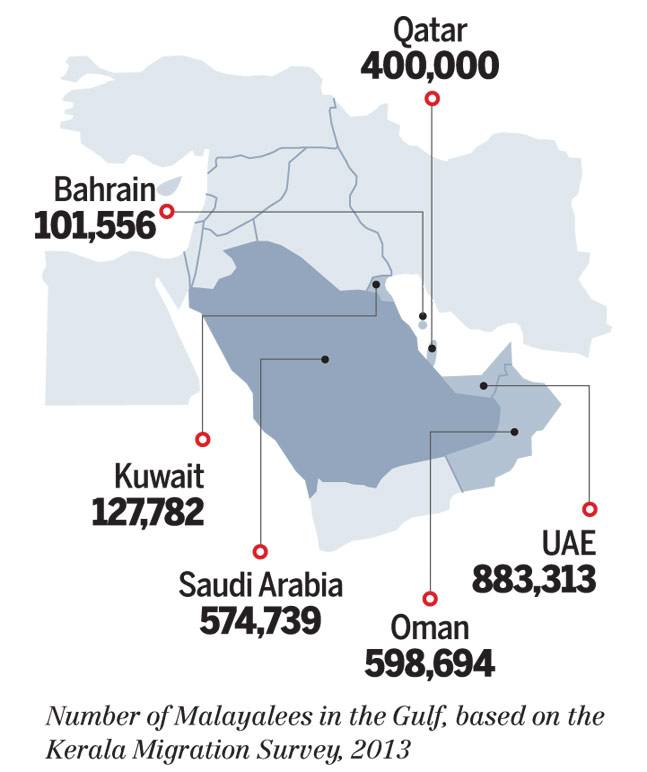

Gulf, Migration to

2013: Malayalis in the Gulf

See graphic:

No. of Malayalees in the Gulf

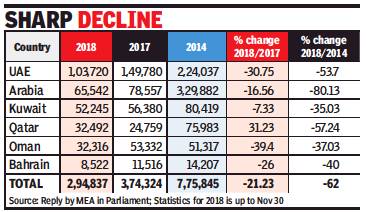

2014> 2018: Migration to Gulf for jobs drops 62%

Lubna Kably, January 12, 2019: The Times of India

Lubna Kably, UAE is top Gulf workplace for Indians, January 12, 2019: The Times of India

From: Lubna Kably, January 12, 2019: The Times of India

From: Lubna Kably, UAE is top Gulf workplace for Indians, January 12, 2019: The Times of India

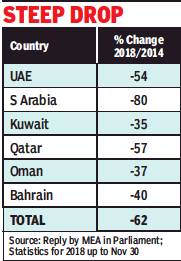

The total number of emigration clearances granted to Indians headed to the Gulf, for employment, has dropped by 21% to stand at about 3 lakh during the 11-month period ended November 30, 2018, compared with the year 2017.

Over the past five years, during 2014, the outflow of Indian workers to Gulf was the highest at about 7.8 lakh. Compared with this figure, the decline in 2018 is as high as 62%. These statistics are drawn from the e-Migrate emigration clearance data, which captures the emigration clearances issued to workers holding ECR (emigration check required) passports.

Among all the Gulf nations, the largest outflow of Indian workers in 2018 was to UAE, with about 1 lakh (or 35%) of the total workers being granted emigration clearances. It was followed by Saudi Arabia and Kuwait with 65,000-odd and 52,000-odd workers headed to these countries.

In 2017, Saudi Arabia had relinquished its position as being the most attractive destination among Gulf countries for Indian workers. In its edition dated August 22, 2017, TOI had analysed the Nitaqat scheme for protection of local workers — the decline in expat workers, including from India is attributed to this scheme and the economic conditions.

Qatar stands out by being the only country in the Gulf region, where the number of workers shows an increase in 2018 as compared to the previous year. Nearly 32,500 workers headed to Qatar were granted emigration clearances, as compared to close to 25,000 in 2017, which is a rise of 31%.

“This could be because of increased labour requirement as the country prepares to host the World Cup, 2022” says a Mumbai based labour recruiter. However, there have been some reports of non-payment to Indian workers by unscrupulous employers, an instance of a construction agency not paying nearly 600 workers was recently in the spotlight. Washington headquartered think-tank, The Middle East Institute, says there are an estimated 6 to 7.50 lakh Indian migrant workers in Qatar, constituting the largest expatriate community and nearly double the number of native Qataris.

According to a reply given by the ministry of external affairs in Lok Sabha last December, there are several reasons for the decrease in numbers. “Prominent among them is that the Gulf countries are passing through a period of economic slowdown primarily because of the slump in oil prices.”

Outward migration from India

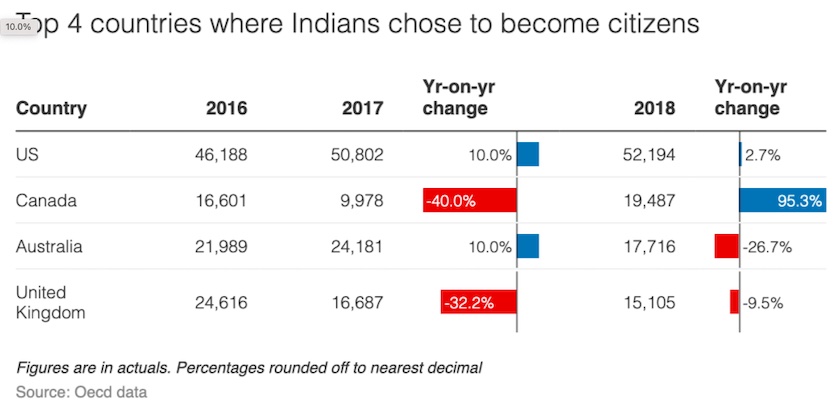

2017, 2018: to OECD countries

Lubna Kably, October 20, 2020: The Times of India

From: Lubna Kably, October 20, 2020: The Times of India

India world No. 2 in migrations to OECD nations, getting citizenships

MUMBAI: India has emerged as the second largest source country both in terms of the “total” inflow of new migrants to OECD countries during 2018 and also as regards the number of Indians acquiring citizenship of these countries. While China continued to retain its top slot as the largest source country, India replaced Romania to emerge as the second largest source. During 2018, about 4.3 lakh Chinese migrated to OECD countries, accounting for nearly 6.5% of the total migration inflows.

However, there was a slight decline of 1% as compared to the previous year. On the other hand, migration from India to OECD countries increased sharply by 10% and reached 3.3 lakh. Migration from India represents about 5% of the overall migration to OECD countries. While Canada saw a huge spike in numbers, others such as Germany and Italy also saw more arrivals as compared to the previous year.

Collation of country-wise data shows that the “total” inflow of new migrants to OECD countries was 66 lakh, a slight rise of 3.8% over the previous year. Data on migra tion flows by nationality may include temporary migration for some destination countries, clarifies OECD. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is an association of 37 member countries, such as European countries, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

As these are well-developed economies, they attract a large share of immigrants, be it for work, studies or even asylum. Before the pandemic, permanent migration flows to OECD countries (bar Colombia and Turkey that have hosted a large number of humanitarian migrants in recent years) was 53 lakh in 2019, with similar figures for 2017 and 2018. Permanent migration flows do not include temporary labour migration or international students.

While releasing the “International Migration Outlook 2020” at a virtual press conference on Monday, Angel Gurría, secretary general at OECD, said Covid-19 has redrawn the international mi gration map. Following the onset of Covid-19, almost all OECD countries restricted admission to foreigners. Issuances of new visas in these countries plummeted by 46% in first half of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. This is the largest drop ever recorded. In the second quarter, the decline was 72%. The secretary general said migration would continue to play a key role for economic growth and innovation, and in responding to rapidly changing labour markets.

Women migrating abroad

2010

Changing times: More women go abroad to work

Divya A |

June 2010

Deepa Gupta, 22, a mathematics graduate from Ludhiana, thought it a great opportunity to go to a postgraduate course in Michigan University. Two years down the line, she is settled in the US and has been joined by her widowed mother.

Gupta represents a trend — that of Indian women increasingly leaving home turf for professional, rather than personal reasons. The World Bank’s report on ‘Gender, Poverty Reduction and Migration’ says more women from developing countries such as India are migrating to the West independently rather than as dependents. It also says that female migration indirectly helps alleviate poverty.

Neelam Soni, executive with an overseas placement agency in Delhi says women in nursing, teaching, social and voluntary work, the hospitality industry, data-entry operations, sales and even housework are able to migrate to foreign shores.

Social scientist Mala Kapur Shankardass says that even though a large proportion of female migration can still be explained away by marriage (estimates say 80%) it is significant that 20% of all women migrants leave for professional reasons. A decade ago, less than 5% of women migrants worked She says that earlier, male migrants used to belong to the ‘Employed’ category and female to the ‘Not in the Labour Force’. This is changing. Shankardass.

But Shankardass cautions that Indian female contribution to forex remittances is still not properly documented. Official data largely focuses on male remittances.

See also

Migration: India