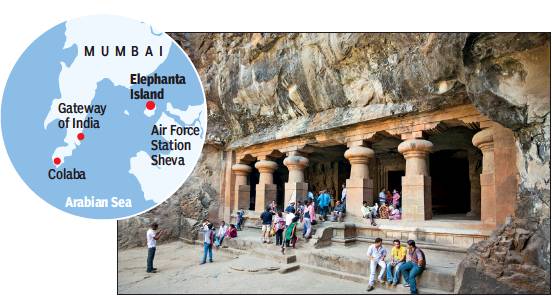

Elephanta Island

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Development

As in 2019

Bhavika Jain1, April 27, 2019: The Times of India

From: Bhavika Jain1, April 27, 2019: The Times of India

40 mins from Mumbai, heritage isle untouched by poll tides

Nearly 25 years ago, Someshwar Bhoir’s wife delivered their first baby in a tiny wooden boat on the Arabian Sea as she was being taken to a doctor at Ferry Wharf in Mumbai. “My daughter Namrata is herself a mother now, but there is still no medical facility here,” said Bhoir, a resident of Shetbunder, one of the three villages on the island.

Wasutai Awate, who sells handmade bracelets and lives in Morabunder village, said expecting women move to their parents’ or relatives’ house as soon as they enter the eight month of pregnancy. “We do not take any risk. We ask pregnant women to leave the island much in advance,” she said. Being taken ill after 6 pm, when the passenger boats that ply to Gateway of India or Uran stop operating, is still a danger. “At such times, locals get their old, rickety boats out and ferry the ill,” said Awate.

South Mumbai is just a 40-minute boat ride away, but Elephanta Island, or Gharapuri as the locals call it, could not be farther away on the development scale. The island got power for the first time last year, after underwater cables were laid.

And the 1,200 residents of the island, a Unesco world heritage site, do not hope for a lot even as another election comes knocking.

The island falls under the Maval Lok Sabha constituency, which was carved out in 2009 from Thane and Raigad constituencies after delimitation, and its 800-odd voters exercise their franchise enthusiastically — about 75-80% turnout is usual — in the lone polling booth in the only school on the island. It is currently represented by Shrirang Barne of Shiv Sena.

“There are tourists who come from America and Germany to visit the caves, but our MP, who lives close by, never finds the time. He has never visited the island,” complained Yeshwant Mhatre, who owns a 50-year-old canteen. It’s not just the pathetic medical infrastructure on the island that he is angry about. He has received electricity bills worth Rs 1.2 lakh since August last year. “I recently paid Rs 53,000. I am not going to pay anymore. Let them take my meter away,” said Mhatre, who lives in Rajbunder village.

“We fall under the Panvel electricity office and to complain about inflated bills would mean keeping the canteen shut and losing a day’s earning. I have gone there several times, but haven’t got any help,” said Mhatre. Before power came to the island, they would get electricity for three hours every day, from 7 pm to 10 pm, and all shops had to run generators for power. Happiness at electrification proved short-lived. Inflated bills is a common problem. Vinesh Gharat received a bill of Rs 18,900 for January. It was Rs 23,350 for December and Rs 18,570 for November. “We have a house in Shetbunder, but my family moved to Uran 10 years ago. Yet we have received such huge bills,” said Gharat, who too was delivered in a boat on a stormy night.

There was little evidence of campaigning, and it isn’t surprising in the face of one all-pervasive complaint: mainland apathy. “One young candidate visited the island. He spoke to us, but they all forget about our problems as soon as they take the boat back to the mainland,” said Radhabai Bhoir. NCP’s debutant candidate Parth Pawar had visited the isle.

Water scarcity was evident as all the houses in the village had big blue drums used to stock water. Tourists climb the 120 steps to the heritage caves once in a while, some even hire makeshift palanquins. But the local women have to do this every day with pots balanced on their heads “as the only source of drinking water is a well near the caves. “We do get non-potable water for bathing and washing once in three days, but drinking water remains a big problem,” said Bhoir.