Padmavati/ Maharani Padmini

See also Padmaavat, the film

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A summary of Jayasi’s story

Nandini Chandra| Siting childhood : a study of children’s magazines in Hindi 1920 50 |shodhganga

The plot of the Padmavat in recounted here in some detail, because it differs substantially from the story of Padmini commonly known today.

Padmavati is the daughter of Gandharvsen, the king of Singhal. At the age of twelve, she is given a palace of her own and starts living there with her sakhiyan. She becomes staunch friends with the parrot Hiraman, learned in the shastras and shrewd. Padmavati and he read the Vedas together. The king resents the parrot's proximity to his daughter and orders the bird killed

A terrified Hiraman bids farewell to Padmavati and flies away, leaving her in tears. In the forest, the parrot is trapped by a bird catcher (baheliya) and sold to a brahman, who takes him to Chitaur. Ratansen, the king of Chitaur, is impressed with Hiraman's learning and buys him from the brahman

( Jayasi provides an allegorical gloss for the fortress kingdom by pmming on its name, Chita-ur (the domain of the mind, chita and heart, ura). 1 use this spelling, closer phonetically to the Avadhi word, to disttress [sic] in Mevar, I use its conventional name and spelling, Chitor. )

The parrot praises Padmavati, the most beautiful of women, to his new master Ratansen

At the mere mention of her, the king burns with longing and the anguish of separation from her (viraha). In spite of the dissuasion of his mother and his first wife Nagmati, he becomes an ascetic and embarks on a quest to win this ideal woman for his wife. Word spreads that the king is setting off for Singhal to win a wife. His vassals and princes, sixteen thousand of them, also decide to accompany Ratansen. With Hiraman as his guide, he reaches the coast, crosses the seven seas, and arrives in Singhal with his associates. There, he begins penance in a Shiva temple in order to win Padmavati. Informed by the parrot of Ratansen' s coming, the princess goes to the temple, but the meditating king is unaware of her presence. She is offended and·retums to the palace, but begins to reciprocate his desire. Ratansen is desolate when he finds out that he has missed an opportunity to meet her. He builds a pyre and sets out to immolate himself "like a sati."

Shiva and Parvati intervene to quench this fire of 'desire' (kama) that threatens to burn down the entire world in its intensity. Ratansen is tested and found true by Parvati. On Shiva's advice, he then launches an attack on the fortress. He and his associates, still in the guise of ascetics, are captured and imprisoned by Gandharvsen. He is about to be crucified for being a mere ascetic and beggar and yet daring to love the princess, when his bard intervenes. His true identity as king of Chitaur is revealed. Gandharvsen marries his daughter to Ratansen. Further, his sixteen thousand associates also obtain sixteen thousand 'Padmini' women of Singhal as reward. Ratansen and Padmavati consummate their desire

Meanwhile Nagmati burns in viraha for her missing husband, and laments her lot. The fire of her viraha threatens to burn down the world once again. At this point, a bird agrees to take her message to Singhal. Ratansen is reminded of home by the bird' s message, and sets out on the return Journey with new wife, her companions (sakhiyan) and his associates. Guilty of the sin of pride at his success in having obtained the most beautiful woman on earth, Ratansen is promptly punished by a storm on the seas. All their associates are killed and Padmavati is marooned on the island of Lacchmi the daughter of the ocean. Meanwhile, Ratansen floats elsewhere on a log in the ocean. Lacchmi takes pity on Padmavati's plight and sends her father the Ocean in search of Ratansen When the drowning Ratansen is rescued by the Ocean, Lacchmi decides to test his love for Padmavati. She appears in front of him in the guise of Padmavati, but Ratansen is not fooled

The king and queen are reunited. The Ocean and his daughter reward them for their constancy, with fabulous gifts and safe return to the mainland. With the help of these gifts, Ratansen finances a new entourage at Puri, and they make the journey back to Chitaur. He has returned triumphant with a new wife as well as fabulous gifts

On Ratansen's retum, Nagmati complains bitterly to him about his having brought back a rival wife (saUt). The king placates her by spending the night with her. This angers Padmavati, who complains in tum. Ratansen now has to placate her in the same way. The two wives come to blows quite literally, and some degree of peace is established in the household only when Ratansen reprimands both his queens

The brahman Raghav Chetan is granted a privileged position at the king's court because of his special magical powers. Challenged by the other brahmans and scholars at the court, he wins the contest by using his magic to deceive the king. When his deception is found out the next day, he is banished by an angry king. Padmavati hears of the matter and summons him, as she wishes to give him her priceless bangle as a placatory gift. The Brahmin is stunned at her beauty and accepts the bangle before leaving Chitaur. He still plans vengeance against Ratansen, however. He goes to Delhi to try and gain an audience with Alauddin Khalji. Summoned to the sultan's court, he is asked about the bangle he wears. He describes the incomparable beauty of Padmavati, a 'Padmini' woman. Such a woman is supreme amongst the four categories of women, and found only in Singhal. However, she is now present in the nearby kingdom of Chitaur

Alauddin lays siege to Chitaur and demands the surrender of Padmavati. The king refuses, but offers to pay tribute to the sultan. The siege continues, and Alauddin finally suggests fresh terms to end the stalemate. Ratansen allows the Sultan to enter the fort and entertains him as a favoured guest. In doing so, he disregards the express warnings of his vassals Gora and Badal

Alauddin catches a glimpse of Padmavati by subterfuge. He then traps Ratansen into accompanying him to the foot of the fort, captures him and takes him back to Delhi. Padmavati approaches Gora and Badal, the two pillars of the kingdom, for help. They plan an expedition to Delhi to rescue their king who is being tortured in the sultan's prison. Disguised as Padmavati and her sakhiyan, they manage to trick their way into the fortress and prison in Delhi, and free the king. On the journey back however, they are discovered. Gora is killed fighting like Abhimanyu as he holds the sultan's army at bay, while Badal reaches Chitaur safely with the king

Meanwhile Devpal, ruler of neighbouring Kumbhalner, takes advantage of Ratansen's absence and sends a brahman woman as emissary to Padmavati. This Rajput king suggests that she give up Chitaur and become his queen instead. Padmavati rebuffs the emissary, and narrates the insult to Ratansen on his return. Ratansen sets off again to punish Devpal, promising to return before Alauddin's forces reach Chitaur. Devpal and Ratansen kill each other in single combat

Nagmati and Padmavati commit Sati. When Alauddin's army arrives, the Chitaur forces go out for their last battle, as their women commit jauhar. Alauddin acquires an empty fortress, cheated of victory even as Chitaur is conquered by Islam

Jayasi’s poem vis-à-vis history

Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag

Interspersed with extracts from Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com

Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction

SNAPSHOT

Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s poem Padmavat, does not have a historical basis.

Rani Padmini was the queen of Chittorgarh, and Alauddin Khilji, the ruler of Delhi.

The popular story says that when Khilji attacked Chittor, he fell for Padmini on seeing her reflection in the mirror. This story was woven by a well-known Indian poet, Malik Muhammad Jayasi, in 1540 AD, and finds echo in Jawaharlal Nehru's Discovery of India as well.

Jayasi’s poem about Padmini and Khilji, however, is not accurate. Historians have, in fact, come up with possible scenarios for what could have actually happened.

According to Jayasi’s poem Padmavat, Rani Padmavati of Chittor was the wife of Raja Ratansen (a name invented by Jayasi with no reference in Mewar history) of Chittor during the reign of Allauddin Khilji. The correct name of Chittor's then ruler was Rawal Ratan Singh, the thirty-fourth descendant of Bappa Rawal. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

What Jayasi’s poem says

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Sultanate of Delhi - the kingdom set up by the invaders was nevertheless growing in power. The Sultans made repeated attack on Mewad on one pretext or the other. Here we may recollect the story of Rani Padmani who was the pretext for Allah-ud-din Khilji's attack on Chittod. In those days Chittod was under the Rule of King Ratansen, a brave and noble warrior-king. Apart, from being a loving husband and a just ruler, Ratansen was also a patron of the arts. In his court were many talented People one of whom was a musician named Raghav Chetan. But unknown to anybody, Raghav Chetan was also a sorcerer. He used his evil talents to run down his rivals and unfortunately for him was caught red-handed in his dirty act of arousing evil spirits. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

On hearing this King Ratansen was furious and he banished Raghav Chetan from his kingdom after blackening his face with face and making him ride a donkey. This harsh Punishment earned king Ratansen an uncompromising enemy. Sulking after his humiliation, Raghav Chetan made his way towards Delhi with -the aim of trying to incite the Sultan of Delhi Ala-ud-din Khilji to attack Chittor. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

On approaching Delhi, Raghav Chetan settled down in one of the forests nearby Delhi which the Sultan used to frequent for hunting deer. One day on hearing the Sultan's hunt party entering the forest, Raghav-Chetan started playing a melodious tone on his flute. When the alluring notes of Raghav-Chetan flute reached the Sultan's party they were surprised as to who could be playing a flute in such a masterly way in a forest. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

From Padmavati Real Story and Ramdev Singh Inda

Done in the European style, this seems to be a 20th century painting.

The Sultan despatched his soldiers to fetch the person and when Raghav-Chetan was brought before him, the Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji asked him to come to his court at Delhi. The cunning Raghav-Chetan asked the king as to why he wants to have a ordinary musician like himself when there were many other beautiful objects to be had. Wondering what Raghav-Chetan meant, Ala-ud-din asked him to clarify. Upon being told of Rani Padmini's beauty, Ala-ud-din's lust was aroused and immediately on returning to his capital he gave orders to his army to march on Chittor. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

But to his dismay, on reaching Chittor, Allah-ud-din found the fort to be heavily defended. Desperate to have a look at the legendary beauty of Padmini, he sent word to King Ratansen that he looked upon Padmini as his sister and wanted to meet her. On hearing this, the unsuspecting Ratansen asked Padmini to see the 'brother'. But Padmini was more wordly-wise and she refused to meet the lustful Sultan personally. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

Desperate to capture the beautiful Padmini, Khilji sent a word to Ratansen about him wanting to meet her. The Raja asked Padmini, who flatly refused. However, on being persuaded by her beleaguered husband, Rani Padmini agreed to let Khilji see her in the mirror. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

On being persuaded by her husband Rana Ratansen, Rani Padmini consented to allow Ala-ud-din to see her only in a mirror. On the word being sent to Ala-ud-din that Padmini would see him he came to the fort with his selected his best warriors who secretly made a careful examination of the fort's defences on their way to the Palace. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

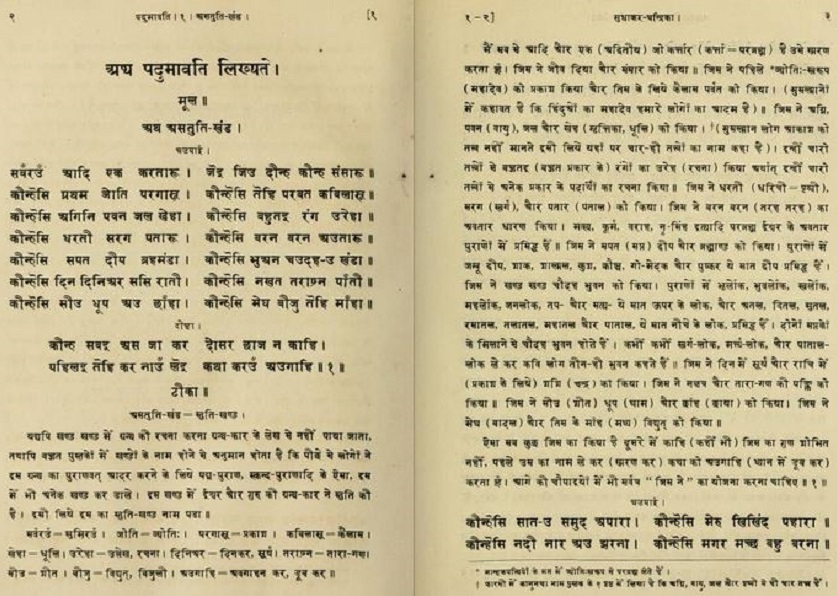

This is a genuine, pre-modern miniature painting. As in a comic book, the story is depicted in the four horizontal panels of the page. Within each panel the story proceeds through individual frames. The jauhar (sati) is in Panel 3, centre. The battle is in the bottom panel.

Khilji had entered the fort with a group of select warriors who had observed the fort's defences on their way to the palace. On seeing Padmini in the mirror, Khilji decided that she must be his.

On seeing Padmini, in the mirror, the lustful 'brother', Allah-ud-din Khilji decided that he should secure Padmini for himself. While returning to his camp, Allah-ud-din was accompanied for some way by King Ratansen. Taking this opportunity, the wily Sultan deceitfully kidnapped Ratansen and took him as a prisoner into his camp and demanded that Padmini come and surrender herself before Ala-ud-din Khilji, if she wanted her husband King Ratansen alive again. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

The Rajput generals , led by two gutsy warriors, Gora and Badal, who were related to Padmini, decided to beat the Sultan at his own game and sent back a word that Padmini would be given to Ala-ud-din the next morning. On the following day at the crack of dawn, one hundred and fifty palanquins (covered cases in which royal ladies were carried in medieveal times) left the fort and made their way towards Ala-ud-din's camps The palanquins stopped before the tent where king Ratansen was being held prisoner. . Seeing that the palanquins had come from Chittor; and thinking that they had brought along with them his queen, king Ratansen was mortified. But to his surprise from the palanquins came out, not his queen and her women servants but fully armed soldiers, who quickly freed ; Ratansen and galloped away towards Chittor on horses grabbed from Ala-ud-din's stables. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

On the following day at the crack of dawn, one hundred and fifity palaquins (covered cases in which royal ladies were carried in medieveal times) left the fort and made their way towards Ala-ud-din's camps The palanquins stopped before the tent where king Ratansen was being held prisoner. . Seeing that the palanquins had come from Chittor; and thinking that they had brought along with them his queen, king Ratansen was mortified. But to his surprise from the palanquins came out, not his queen and her women servants but fully armed soldiers, who quickly freed ; Ratansen and galloped away towards Chittor on horses grabbed from Ala-ud-din's stables. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

On hearing that his designs had been frustrated, the lustful Sultan was furious and ordered his army to storm Chittor. But hard as they tried the Sultans army could not break into the fort. Then Ala-ud-din decided to lay seige to the fort. The seige was a long drawn one and gradually supplied within the fort were depleted. Finally King Ratnasen gave orders that the Rajputs would open the gates and fight to finish with the besieging troops. On hearing of this decision, Padmini decided that with their men-folk going into the unequal struggle with the Sultan's army in which they were sure to perish, the women of Chittor had either to commit suicides or face dishonour at the hands of the victorious enemy. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

When Khilji entered the fort, all that he found were ashes of these brave women. Their sacrifice has been kept alive by Bards in their songs, where they praise women who preferred supreme sacrifice to dishonour.

From Padmavati Real Story. Though done in the traditional style, this seems to be a later painting.

The choice was in favour of suicide through Jauhar. A huge pyre was lit and followed by their queen, all the women of Chittor jumped into the flames and deceived the lustful enemy waiting outside. With their womenfolk dead, the men of Chittor had nothing to live for. Their charged out of the fort and fought on furiously with the vastly Powerful array of the Sultan, till all of them perished. After this phyrrhic victory the Sultan's troops entered the fort only to be confronted with ashes and burnt bones of the women whose honour they were going to violate to satisfy their lust. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

These women who committed Jawhar had to perish but their memory has been kept alive till today by bards and songs which glorify their act which was right in those days and circumstances. Thus a halo of honour is given to their supreme sacrifice. (Rani Padmini - A legendary beauty, Chittorgarh.com)

From Padmavati Real Story and Ramdev Singh Inda

Done in the European style, this seems to be a 20th century painting.

When author Ram Ohri visited Chittorgarh Fort in 2008 and asked the guide about the veracity of the mirror story, he said locals did not believe in it.

Having learnt what Jayasi's poem says, let us now read what the Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan's book on Indian History says. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan's history

In January 1303, Khilji set out on his memorable campaign for the conquest of Chittor. He received strong resistance from the Rajputs under Rana Ratan Singh. The Rajputs offered heroic resistance for about seven months and then, after the women had perished in the flames of jauhar, the fort surrendered on August 26, 1303.

Whilst later writers like Abu-l Fazl, Haji-ud-Dabir (note these two authors use Padmini not as a name, but as a woman possessing special attributes) have accepted the story that the sole reason for invasion of Chittor was Khilji’s desire to get possession of Padmini, many modern writers are inclined to reject it altogether. They point out that the episode of Padmini was first mentioned by Malik Jayasi in 1540 A.D. in his poem Padmavat, which is a romantic tale rather than historical work. Further, the later day writers who reproduced the story with varying details, flourished long after the event, but their versions differed from one another on essential points. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Yarn 2 by Jayasi

In Padmavat, Jayasi wrote that Padmini was the daughter of Raja Gandharva Sen of Sri Lanka. The Lanka story has many contradictions. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

1) The name Raja Gandharva Sen is nowhere found in Sinhalese history. The then Buddhist rulers of Lanka had contacts mainly with the Pandya kings of Tamil Nadu and none with Rajputana. The names of Lanka rulers at the time were Vijayabahu III (1220-24), Bhuvanaikabahu I (1281-83), Interregnum (1283-1302) and Vijayabahu V (1325-26 to 1344-45). (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Instead, there is a strong possibility that Padmini was a princess of Jaisalmer or of Sinhala, a village near Sojat in Pali district of Rajasthan. In the history of Rajasthan, there are many references which indicate that Rani Padmini was the eleventh wife of Rawal Ratan Singh among his fifteen wives, as polygamy was prevalent among Rajput rulers then. There is, however, no confirmation of her father being Rana Salsi Tanwar as written in the book The Kingdom of Mewar by Irmgard Meininger, a German author. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

2) In Padmavat, there is a reference to a parrot who flew all the way from Sri Lanka to Chittor as a messenger to inform Raja Ratansen, or Rawal Ratan Singh, about the beauty of Padmini, daughter of the Sinhala ruler Gandharvasen, making Ratansen travel all the way to the Sinhala kingdom to win the hand of Padmini. This narrative lacks credibility since Lanka never had a king by that name. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

3) Jayasi wrote this poem almost 237 years after Khilji's attack on Chittor. The literature of that era is full of highly imaginative narratives, and poets were known to gleefully use metaphors, alliterations and imaginary personifications. There is also a reference in Padmavat to a sorcerer called Raghav Chetan, who is believed to have been personified as a parrot. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Contradictions in Jayasi's poem

Amir Khusro, the court poet of Khilji, who accompanied him during the Chittor attack, did not write about Padmini, nor did he allude any episode to her in his book Twarikh-e-Allai. To be fair, it is possible that Khusro might not have wanted to further spoil the image of Khilji. So he ignored the reference to Padmini. "According to Prof Habib, there is a covert allusion to Padmini episode by Khusro in his Khazain-ul-Fatuh, where he mentions the Queen of Sheba." (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Equally important is the fact that Col James Tod did not refer to Khilji's desire to capture the beautiful Padmini in his book The Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

There are many instances in history when court poets and writers have followed the instructions of the ruling kings, and wrote histories accordingly. For instance, the book Ain-i-Akbari by Abul Fazal, where he was instructed not to write about Mehrunissa's -- later known as Nur Jahan, wife of Mughal King Jahangir -- first marriage with an Afghan Pathan. However, there is a mention of her in Tuzuk-e-Jahangari as his beloved, and how his father had cheated on him. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

It would not be wrong to say that Jayasi's poem Padmavat is a figment of his poetic imagination. "It has also been argued that the invasion of Chittor was the natural expansionist policy of Khilji and no Padmini was need for his casus belli". (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

The story of Khilji watching Padmini’s reflection in a mirror, or in a well, as stated in Discovery of India by Pandit Nehru, could have been based on a latter-day interpolation by some local poets. It could also be a phoney myth popularised by some imaginative storytellers. (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

Having questioned the motive for Khilji's invasion of Chittor, "it should be remembered that Khilji's lust for a Hindu queen is proved by the known instances of Queen Kamala Devi of Gujarat and the daughter of King Ramachandra of Devagiri. The story of Padmini should not be totally rejected as a myth. But it is impossible, at the present state of knowledge, to regard it definitely as a historical fact". (Ram Ohri, Rani Padmini And Alauddin Khilji: Separating Fact From Fiction, Jan 28, 2017, Swarajya Mag)

References

1. Volume 6 of the History and Culture and Indian People, published by the Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, p 23

2. Rani Padmini - a legendary beauty

3. The Indian Express, 28 January 2017, p 11

Fact, fiction, epic poem, cinema

Sufi poet Jayasi made up the story that later got legend status, so Bhansali can't be threatened for taking creative license with the tale, say historians

Sanjay Leela Bhansali's upcoming film, Padmavati, is a story about a story. It is based on a 16th century literary saga by Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi, a romantic fiction about Delhi sultan Alauddin Khilji's sack of Chittor which itself had occurred over 200 years earlier, in 1303. In Jayasi's allegorical poem, a Rajput queen of Chittor chooses to immolate herself rather than submit to the sultan.

The myth, written in Avadhi in 1540, 30 years before Tulsidas began his Ramcharitmanas, has ended up being taken literally as history . It created, out of whole cloth, the legend of Padmini or Padmavati, the Ceylonese princess turned loyal queen --there is not a shred of historical evidence that she existed.And because of the popularity of the epic, the actual Alauddin Khilji, destroyer of the Mongols and one of India's most able administrators, is only remembered as a thwarted lover-boy , whose obsession and lust for another man's wife leads him to destroy a kingdom. The legend has been passed down as popular history for years and used to demonise Islamic empires. And now, custodians of that made-up `history' have used it to attack another cultural work -storming the sets of Bhansali's forthcoming period drama Padmavati, at Jaipur's Jaigarh fort.

Vigilantes of the Karni Sena, self-appointed defenders of Rajput honour, allegedly slapped and intimidated the director into changing some material. Narayan Divrala, the district president of Karni Sena, was quoted as having said, “We have learnt that the filmmakers are portraying the film as a love story between Alauddin Khilji and Padmini, which is a blatant distortion of history .“

Bhansali's film unit was forced to leave Jaipur, and the fracas has led to predictable battles on social media, between those who condemned the bullying and those who applauded their action. Some Twitter warriors even claimed that Bhansali was funded by Pakistan's ISI to make a “profane and offensive“ movie to hurt Hindus and ridicule their history .

But what was the Delhi-Chittor conflict about? “ A campaign of conquest has multiple historical causes, which may or may not include the personal preferences of a ruler.Chittorgarh was coveted by the Delhi sultans for strategic and com mercial reasons. With the passage of time, events became imbued with cultural meanings, which have more to do with politics and less with history ,“ says Delhi University historian Anirudh Deshpande.

Did Jayasi himself claim to be chronicling history? According to the Imperial Gazetter of India, 1909, “in the final verses of his work, the poet explains that it is all an allegory . By Chittor he means the body of man; by Ratan Singh, the soul; by the parrot, the guru or spiritual protector; by Padmavati, wisdom; by Alauddin, delusion, and so on.“

It explains the ideals that animated Jayasi's noble e pic: “Throughout the work of the Musalman ascetic, there run veins of the broadest charity and of sym pathy with those higher spirits among his fellow countrymen who were searching in God's twilight for that truth of which some of them achieved a clear vision.“ In other words, the Sufi poet was using his creative licence to convey a philosophical message. And that creative licence is exactly what Bhansali is now being punished for.

'Rani Padmavati never existed'

It is said that the story of Rani Padmavati, also known as Padmini, and Alauddin Khilji’s siege of King Rawal Ratan Singh’s Chittor took place in 1303. However, noted historian S Irfan Habib argues that Rani Padmavati was not a historical figure as there is record of her before 1540. According to him, the queen was a fictional figure created in the poem, ‘Padmavat’ written by Malik Mohd Jayasi in 1540.

The poem had famously traced the story of Padmini, Alauddin Khilji and Rawal Ratan Singh.

Habib took to Twitter to express his views, also finding similarities with the character Anarkali, shown in films like ‘Mughal-E-Azam’, who he also claims was not a historical character but a fictional one.

Habib pointed out that ‘Prof KS Lal and Prof Gauri Shankar Ojha, an expert on Rajasthan history find nothing before Padmini legend was created in 1540.’

Jayasi’s Mythical Spiritual Conduit

Sumit Paul | Padmavat: Jayasi’s Mythical Spiritual Conduit |21 Nov 2017|The Times of India

‘Padmavati’, must be seen and understood against the backdrop of Persian mysticism, spirituality and poetry, to get a comprehensive picture of the whole issue.

The subcontinental mystic-poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi wrote ‘Padmavat’ in 1540 AD and deliberately created a female character to be eventually deified in accordance with Persian mystical traditions and also as one of the indispensable 16 rules of Persian spiritual poetry that were religiously followed by all Central Asian and subcontinental poets of Persian mysticism including Amir Khusrau from Hindustan and Rumi, Hafiz, Sanai and others from Iran.

The language of Jayasi’s ‘Padmavat’ was Avadhi, the dialect of Avadh, but the original script was Persian. Before descanting upon how and why Jayasi thought of creating a character like Padmavati, it’s worthwhile to mention Muhammad Iqbal’s letter to young Raghupati Sahay Firaq Gorakhpuri, which the former wrote to the latter in 1929, when Firaq was a young lecturer of English at Muir College, Allahabad.

Here’s that relevant passage: “For an Islamic mystic, woman is always a catalyst or medium to reaching higher consciousness. She could also be his imaginary muse, unadulterated and unspoilt by thought and action. She’s an indispensable character whether fictitious or real, but mostly the former, because only a fabricated – male or female – character can be so divinely chaste. Jalaluddin Rumi’s Irfa, Nizami’s Nahila, Attar’s Qaneem, Hakim Sanai’s Aviara did never exist, but they were woven and assimilated into poetic plots by all mystics so beautifully, that with the passage of time, they began to appear as real-life characters. Poetry, especially Islamic tasawwuf – spirituality based poetry always has a central or powerful clandestine female character, who’s often unreal.”

The invariable end of this fictitious character – as in Padmavati’s jauhar (ritualistic self-immolation) in Jayasi’s Padmavat – is a symbol of the end of the last obscure vestiges of carnality necessary for union with the universal mind.

The inviolability of a woman’s character and her elevation to the highest pedestal can be seen in Jayasi’s ‘Padmavat’. It’s interesting to note that in Central Asian mystic traditions, self-immolation is unIslamic. But Jayasi’s mysticism was rooted in the ethos of the subcontinent and he used jauhar as a symbol of coordinating a composite vein of Hindu-Muslim unity. Despite himself being a Muslim, Jayasi didn’t present Khilji in positive light. The same spiritual poetic tradition was followed by the Iranian predecessors of Jayasi like Rumi, Hafiz, Jami and Bedil among others.

Persian mysticism looks at a woman as ‘alamat-e-paakeezgi’ – the ‘perfect symbol of purity’. She cannot be defiled – just like Padmavati, who couldn’t be desecrated by the ‘lascivious’ Alauddin Khilji. Moreover, according to an unverified account mentioned by Colonel James Tod in his tome, ‘Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan’, Jayasi was enamoured of one Rajput damsel, Padma, whom he got to see somewhere near Ajmer, Rajasthan. No further description is given in the book. It is, therefore, surmised that he immortalised that Padma as Padmavat, both as his spiritual muse and also as a necessary cog in the scheme of Persian mysticism.

(The writer is a scholar of Islam and Persian)

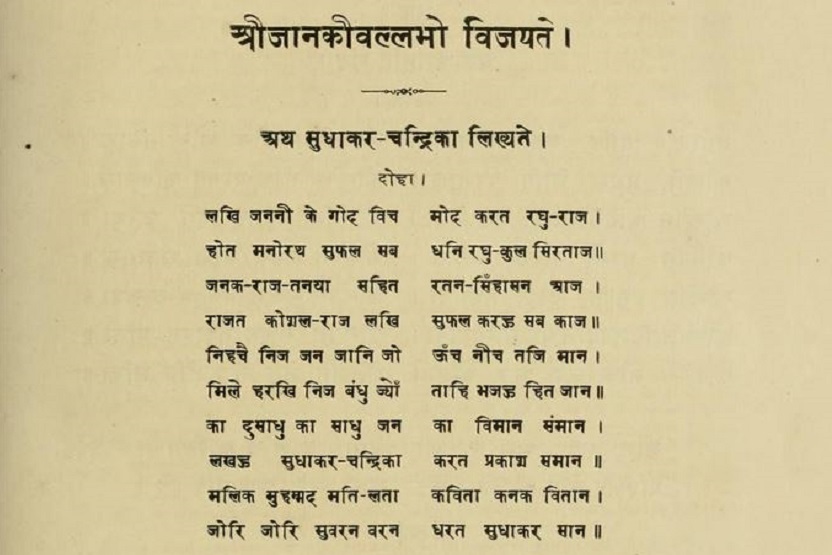

Padmawat: the book, its editions, cover versions and critiques

Malik Muhammad Jayasi sure composed his magnum opus Padmavat, glorifying a Rajput legend of valour, and casting one of the most powerful, competent Muslim kings as the villain of his narrative. Why is there an issue with Padmavati despite Sanjay Leela Bhansali reiterating that his movie is based on Jayasi's work?

Malik Muhammad Jayasi belonged to the Chishtia order of Sufis. His miracle-legends have been part of popular memory. The most stunning miracle he performed -- the Padmawat -- has been around physically for five centuries. Jayasi composed his magnum opus in 1540 in Awadhi, its manuscripts were mostly found written in the Persian script. Taking the legend of Padmini from the oral traditions of Rajputana, Jayasi created a fascinating texture of legend, history and mythology (Hindu as well as Islamic), drawing liberally from his vast knowledge and life experiences. Padmawat was apparently an instant hit in the literary circles of north India, and was also translated into Bengali in the sixteenth century itself. Thus, to Jayasi goes the credit of taking the Padmawati legend to Bengal; wherefrom a number of novels, plays and poems glorifying the Rajputs were to emanate in the nineteenth century.

Ever since Ramchandra Shukla, the most influential historian of Hindi literature, published his edition of Padmawat (1924), its excerpts have inevitably been included in Hindi syllabuses, from schools to post-graduate programmes. Shukla situated the text in a historical context in which after initial conflicts, Hindus and Muslims were coming to terms with each other: "A century ago, Kabir had already castigated bigotry of every kind. One is not sure of the pundits and mullas, but ordinary people had recognised the unity of Ram and Rahim...only those sadhus and fakirs could hope to win popular admiration who seemed beyond discriminating on religious lines... For Hindus and Muslims alike, it was time to open up to each other. People were tending towards sharing rather than distancing. Muslims were willing to listen to the Ram story of the Hindus and Hindus were ready to hear the Dastan of Hamza... and sometimes both tried to explore pathways to God together."

To Shukla, Padmawat was a luminous signpost of this shared search of the pathway to God. He wrote about Padmawat with as great a passion and critical acumen as he did about his most favourite poet - Tulsidas. Taking a cue from the "last stanzas" of the epic, which supposedly "hold the key" to Sufi content "hidden" in the text, he thought it was an allegory of Sufi spiritual practice. But, Mata Prasad Gupta, the great text-critic and scholar of the early modern vernacular literature of north India, in his edition of Padmawat (1963), based on a comparative study of sixteen manuscripts of different periods, comes to the convincing conclusion that the so-called 'key stanzas' were "added to the text much later." He concludes that far from an allegory of any kind, Jayasi was, in fact, composing a richly layered poem of human desire and love.

Jayasi was a practising Sufi, but he did not compose Padmawat to propagate or preach Sufism or any other edition of Islam. He wrote it to celebrate human love, luxuriating in all its aspects - desire, wandering, coupling (described in uninhibited, moving erotica), jealousy, separation, struggle, suffering and sacrifice. If at all he wished to preach anything, it was human, carnal love, which in its deep reaches becomes sublime and transforms the mortal human into the immortal and divine ('manush prem bhayau baikunthi'). At the end of his epic, he is confident that 'anybody listening to this poem, written in blood and tears, is bound to feel-and sing-the pain of love him/herself'. He writes of the inevitability of death and identifies with the universal human desire to leave behind memories: "Who in this world does not long for abiding fame? / I hope the readers of this story also remember my name."

His hope did bear fruit. Even if he is not as popular among the masses as Kabir, Tulsi, Mira or Surdas, his Padmawat fired the imagination of scholars of both literature and history. Apart from Shukla and Gupta mentioned here earlier, the two most important works are: a fascinating Bhashya (a scholarly commentary) on Padmawat by Indologist Vasudeva Sharan Agrawal and a thought-provoking monograph by eminent poet, critic and Lohia acolyte Vijay Dev Narain Sahi.

It is important to internalise all this to see the current controversy in perspective. Please note that Jayasi glorified a Rajput legend of valour, and in the process cast one of the most powerful and competent Muslim kings as the anti-hero of his narrative. But, he was not penalised by his Muslim peers or benefactors. He presented a brahmin Raghava Chetan as the real villain of the piece, and brahmin sentiments were not hurt. He described with abandon the beauty of Padmini and her love-making with Ratansen, he did not hesitate to describe the jealous fights between Padmawati and Nagmati (Ratansen's first wife) and Rajput modesty was not outraged.

As is expected of a great poet, Jayasi put love and life in the ultimate existential perspective of transience in the face of impending death. In a poignant poetic move, at the end of his saga, Jayasi makes victorious Alauddin reflect not only on his pyrrhic victory (duly noted in the ironic manner he talks of how 'Chittor was taken over by Islam') but also on the nature of insatiable desire. He picks up Ratansen's ashes from his pyre (also the pyre of his two wives) lamenting: 'I actually wanted to avoid this' and continues, 'Desire is insatiable, permanent / but this world is illusory and transient / Insatiable desire man continues to have/ Till life is over and he reaches his grave.'

Contrast this poignancy with the absurd theatre playing out around a film that in all likelihood will only reiterate smug, self-satisfied stereotypes of Rajput 'valour'. The 'warriors' are announcing rewards for chopping off a woman's nose ostensibly in defence of the honour of another. It's not really about the honour of a woman, but an unmitigated male chauvinist fantasy that denies the woman any individuality, a chauvinism that finds expression in a woman self-immolating or in widow-burning. The glorification of this medieval fantasy continues unfortunately, in subtle and not so subtle ways. Bhansali's film is going to contribute to this glorification. This is the sub-text of claims that the film actually upholds Rajput 'honour'.

Personally speaking, I just detest Bhansali's obsession with vulgar opulence and cannot forgive him for massacring the beautiful self-destructive tragedy of Devdas. But criticising someone for lack of subtlety or genuine understanding of a subject is one thing and issuing death threats is quite another. It is no surprise that many BJP leaders are implicitly or explicitly endorsing such threats. Of late, the Congress chief minister of Punjab has also endorsed the 'right to nurture hurt sentiment'. The violence of 'hurt sentiments' persists despite the 'No Objection' certificates issued by journalists Ved Pratap Vaidik, Arnab Goswami and Rajat Sharma, none of whom can be 'accused' of being left-liberal or 'sickular'.

It's true that 'freedom of expression' is not limitless, but the limits are set by law, not by armed mobs invoking hurt sentiment. Also, irrespective of the historicity or otherwise of the persona of Padmawati, even an artist as uninspiring as Bhansali has a right to poetic licence. Given the present state of historical knowledge, the character of Padmawati can only be described as legend, and legends happen to be more deeply entrenched in the cultural memory of a people.

This begs the question: what makes your memory or sentiments so brittle? Even if someone has a different take on a shared memory, why should it bother you if you are so attached to it? Asking this question will take the wind out of the politics of hurt sentiment, and put the matter in the realm of rational enquiry which, of course, is anathema to all warriors of hurt sentiments.

Finally, the absence of rational argument doesn't by any means indicate the absence of calculation. There is nothing 'spontaneous' about organised, aggressive display of hurt sentiment of any kind. It is always politically motivated, the gist of which comes out clearly if the right questions are asked. So, ask why there is no outrage against the boss of the production house. Ask if it's mere coincidence that just before the Gujarat elections, the electronic media is obsessing about this 'burning' issue while ignoring seemingly 'mundane' issues like the Rafale deal, the plight of farmers and the bloodshed on the jobs front.

Among all bhakta and sufi poets, Jayasi was the most insistent on his poetic persona. He was also painfully conscious of his 'ugly' appearance and bodily deformities, and confronted them with confidence in the power of his poetry: "Muhammad, poet of love, ugly and frail, causes laughs and jeers / but hearing his verses, nobody can hold back tears."

The poet was conscious of his bodily deformities and could use his poetry as an antidote. Are we willing to face the deformities of our souls, our minds? Are we blessed with an antidote, or just condemned to inch towards a fractured social psyche, a violent society and a dysfunctional state?

(The author is a leading scholar of early modern vernacular literature, a novelist and public intellectual)

See also

Padmavati/ Maharani Padmini

…and also

Of the various Indpaedia pages on Mewar, the page

Mewar 08: Historical facts furnished by the bard Chand

tells the story of Padmini.

However, may also like to see

Mewar 05: Alleged Persian extraction of the Ranas

Mewar 06: Samarsi, Mahmud's Invasion

Mewar 09: Delicacy of the Rajputs

Mewar 10: Succession of Kumbha

Mewar 11: Banishment of the Charans

Mewar 12: Accession of Rana Sanga

Mewar: Stability of Mewar State