Pakistani Cuisine

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

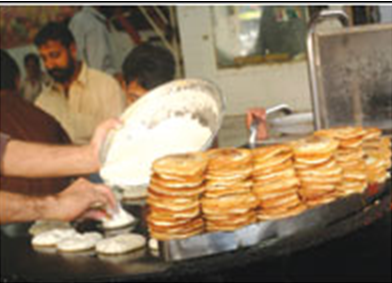

Bun kebab

FOOD FOR THOUGHT: The feisty little bun-kebab

By Qasim A. Moini

Although a simple patty in a bun, bun-kebabs perhaps, are a strong symbol of the class struggle, as they are the proletariat’s favoured snack served up from countless stalls dotting each and every locality in the sprawling metropolis of Karachi.

From Tariq Road to Teen Hatti and beyond, bun-kebabs of varying types and quality can be found, usually sold from a souped-up push-carts or some other almost mobile structure; one can have a quick, tasty snack on the go for under Rs20.

On the other hand, the fare that the multinational burger and chicken franchises peddle costs about five times as much, served up by a smiling, uniformed staffer, under the watchful, Orwellian gaze of a pasty faced clown or goateed colonel. Whereas the bun kebab symbolises all things Urdu medium, the burger, at least in the Pakistani context, represents all things elite and western (read American), and the cultural baggage this entails.

But class divisions and the role food plays in defining these is perhaps a topic for another day. Instead, I’ll let this be a humble homage to that uncrowned king of Pakistani street food: the bun kebab.

For the sake of those who might have been living under a rock for the past few decades, I’ll offer a quick description of what a bun kebab is: in simplest terms, it is a kebab, or ground meat patty, enclosed within a bun. But isn’t that essentially what a burger is? Here, my friends, is the catch. You see, the burger and bun kebab are like two long-lost twins who have rediscovered themselves after a lifetime apart. Though they may share the same basic structure, their culinary evolution has ensured their individual identity.

Even though many bun kebab-wallahs, perhaps in moments of self-doubt amplifying a latent inferiority complex, refer to their concoctions as burgers, the difference between burgers and bun-kebabs is a fine one. And for the discerning foodie, this fine difference is as clear as day.

The very aroma of a bun kebab being prepared at a roadside stall sets it apart from a burger. The trained nose of any sensitive gastronome will detect the scent of a bun kebab from a mile away. And delving a little deeper into the nature of bun-kebabs, one realizes just how much of a separate identity this snack has carved out for itself.

Though labelled a ‘kebab’, in my culinary adventures across this city, I have noticed that the presence of meat in bun-kebabs is negligible. And considering the appalling hygiene standards of most of our foods — both street fare and the stuff served up at proper establishments — perhaps this is a blessing in disguise. Still, the bun kebab-wallah will usually offer you two choices: a meat version or a potato patty. After you’ve made this crucial choice, you can also choose to add fried egg, which I would highly recommend, as it adds a definite kick to the final product.

After these details are out of the way, the chap will start frying your patty and your egg, along with toasting the bun. This, one must say, also enhances the flavour of the bun kebab tremendously, as the crisp bun complements the mushy contents within perfectly. Apart from the aforementioned ingredients, most bun kebab ‘chefs’ also add a generous helping of onions along with a sliced cucumber or two, with some even throwing in a slice of tomato, though this is rare.

But what would a bun kebab be without the condiments? The usual suspects are a somewhat a dodgy ketchup-looking stuff along with a tangy chutney (coriander, green chillies or tamarind are the secret ingredients, methinks) that simply takes the cake. Once the hot-off the-stove bun kebab is doused in this chutney, new dimensions of taste open up.

Some bun kebab-wallahs have started adding desi French fried potatoes, but for some reason it just doesn’t work; instead it ends up spoiling the experience. Though burgers and fries are a somewhat the most appropriate combination, bun-kebabs and chips is just not the done thing.

And since I’ve praised the humble bun kebab to high heaven, I feel it is my civic duty to also inform you about the hazards involved. You see, even though the bun kebab is an awami food, the hygiene standards at many joints selling the stuff are abysmal. Here, the burgers have a clear edge as, even though they may clog your arteries, they are mostly prepared in hygienic conditions.

Bun kebab-wallahs, on the other hand, are far less concerned with health and safety requirements. As with all street food, just use your common sense. If there is a steam of raw sewage flowing next to the bun kebab thela or if your patty is being flavoured with noxious vehicle exhaust free of cost, look for another joint, unless of course you want to battle with a nasty bout of gastroenteritis.

Eid Table

The Eid Table

By Saira Abdullah

see MUZÂFAR n SHEER KHURMA, SPECIAL

Lassi

FOOD: Lassi — A Traditional Drink

By Maliha N. Khan

Pakistani cuisine is as diverse as its people. Among the drinks or beverages consumed in Pakistan, lassi, is quite popular. It is a traditional Pakistani dairy beverage, originally from Punjab, made by blending yoghurt with water, salt, and spices (depending on the type of lassi) until the drink becomes frothy. It is consumed by over one billion Asians throughout the world. With its smooth, cool and refreshing taste, it is the perfect accompaniment to the hot and spicy flavours that epitomise Pakistani cuisine. This traditional drink is economical and plentiful in Pakistan, where cows and buffalo provide an overflow of dairy-based recipes. Traditional lassi is sometimes flavoured with ground roasted cumin. In Punjab lassi sometimes uses a little milk and is topped with a thin layer of malai, clotted cream. Lassi is enjoyed chilled as a hot-weather refreshment. With a little turmeric powder mixed in, it is also used as a folk remedy for gastroenteritis.

Lassi was once the preserve of India’s Maharajas. It is mentioned in ancient Indian texts and was widely used in Hindu rituals. In old times, people would have lassi because they wouldn’t get hungry quickly afterward; and they could wait until lunch to eat again. Tart and refreshing, lassi serves to cleanse the palate alongside spicier foods. It aids digestion and is a healthy addition to any balanced diet. Lassi is 100 per cent natural and is free from artificial colourings, preservatives and flavourings. Besides offering health benefits, lassi is also indulgent and can be enjoyed with or between meals.

There are many types of lassi that are now available. Sweet lassi is a more recent invention, and has become immensely popular. It is consumed mainly in Pakistan during the hot summer months. Rose water is a common ingredient for sweet lassi and adds a sweet, perfumed aroma. Sweet lassi can be flavoured with any fruit of choice like mango, pineapple, banana, lychee, strawberry, etc.

The traditional lassi is a salty yoghurt drink which has a thicker consistency as compared to buttermilk. It can be savoured with various spices and ingredients, but it almost always includes ground cumin powder.

Salty lassi is not only extremely easy and quick to make but also very refreshing and cooling to beat the heat of summer.

Salty Lassi

Ingredients

3 cups plain yoghurt

1 cup cold water

1 fresh green chilli, seeded and very finely chopped

½ tsp ground cumin seeds

Salt and pepper to taste

Fresh cilantro (coriander) or mint leaves to decorate

Crushed ice to serve

Method Pour the yoghurt and water into a blender and blend for one minute. Add in chilli, cumin, salt and pepper and blend together. Serve over crushed ice.

Garnish with a sprinkle of cumin powder and finely chopped coriander or mint.

Plain Sweet Lassi

Ingredients 1 green cardamom pod 100 ml natural unsweetened yoghurt 1½ tsp caster sugar 1 tsp rose water 200 ml cold water 4 mint leaves

Method Use the back of a spoon to gently crush a green cardamom pod, until it splits. Remove the seeds with your fingers, and put the seeds into a mixing bowl or jug, along with the yoghurt, sugar, rose water and water. Use a blender to blend the mixture into a smooth paste. Pour into glasses. Garnish with a sprig of mint.

Here are some other flavours of lassi:

Mint Lassi

Ingredients 5 tbsp finely chopped mint leaves 2 cups plain yoghurt 1½ tsp rock salt (kala namak) ½ tsp roasted, ground cumin seeds ½ tsp salt or to taste 1 cup of chilled water 4-6 ice cubes

Method Put yoghurt, mint, cumin seeds, rock salt in a blender. Blend for a few seconds. Add chilled water and ice cubes. Blend till frothy. Serve sprinkled with a pinch of ground roasted cumin powder and finely chopped mint.

Banana Lassi

Ingredients: 150 gm ice cube, crushed well 150 ml ice water 150 gm natural yoghurt 2 very ripened banana, peeled and roughly chopped 1-2 tsp honey (optional) 1 pod crushed cardamom

Method Blend all of the above ingredients together in a blender. Served chilled and garnish with slices of banana.

Strawberry Lassi

Ingredients

3½ cup fresh strawberry, trimmed and halved

1/2 cup sugar

¼ tsp ground cardamom, rounded

1 pinch salt

2 cups plain yoghurt (whole milk or low-fat)

1 cup ice cubes

Method Blend strawberries with sugar, cardamom and a pinch of salt until smooth. Add yoghurt and ice, then mash until smooth again.

Nowadays, summer is at its peak and the juicy, pulpy mangoes have empowered the whole market scene. Be it Chaunsa, Langara, Sindheri! This is the best time of the year to make mango lassi. Mango lassi is very easy to make. It’s best made with fresh mangoes but can also be substituted by canned mangoes or even mango juice.

Mango Lassi

Ingredients 1 cup plain yoghurt ½ cup mango pulp or pieces of mango 1 cup crushed ice 3 tbsp sugar / use sugar substitute if desired

Method Blend all of the above ingredients. Add a little water if the consistency is too thick. Keep refrigerated. Serve chilled. Garnish with a sprig of mint.

Lassi is a versatile drink which allows you to experiment with different flavours. Only the yoghurt, sugar, water and ice are the basic ingredients that remain the same. Don’t be afraid to make your own lassi using a combination of fruits or things you love. Use lemon zest for lemon lassi, try an apple-mango lassi, add some chopped nuts in your lassi, use a vanilla pod or extract to make vanilla lassi then you can add a swirl of chocolate in it, add a hint of nutmeg to it...use less water, freeze it and you have a frozen dessert — lassi ice cream! The variations are endless so have fun and customise you lassi!

Some interesting lassi facts:

- Lassi is called MAHI in Nepal.

- Lassi may be prepared either from whole or skimmed yoghurt. When yoghurt, made from whole milk, is churned by traditional methods, the butter yield is much below the theoretical level. As a matter of fact, the fat globules are scattered in the liquid phase and the losses of fat in buttermilk are more important than when butter is made from cream. However, lassi prepared from soured skimmed milk has a weaker taste and flavour than that prepared from the buttermilk obtained from yoghurt made from whole milk.

- Lassi is also of great importance in diet. It contains fat, protein, lactose, ash, calcium, phosphorus. So it has a great nutritional value.

- Regular consumption of lassi reduces the chances of your hair going white before time.

Muzâfar

By Saira Abdullah

Ingredients

375 gms sugar 1 cup water ½ cup ghee 250gms vermicelli 1kg milk Saffron 6 cardamoms, crushed Almonds, cashew nut, and pistachios, blanched and silvered

Method Cook the sugar and water till you have slightly thick syrup. In another pan, heat the ghee and fry the vermicelli till it is brown. Add milk and cook over low heat till the milk dries. Add the syrup, saffron and cardamoms. Cook till dry. Sprinkle the nuts on top and serve.

Sajji

FOOD FOR THOUGHT: A nomadic treat

By Mir Mohammad Ali Talpur

The tradition of ‘sajji’ is closely interwoven in the texture of Baloch hospitality coupled with harsh economic reality and environment of Baloch life. It provides much-needed nutrition and an occasion for camaraderie in a nomadic lifestyle.

The word ‘sajji’ conjures up images of roasted meat for those who have enjoyed this essentially Baloch food item. It is the only method in which meat retains its natural taste. It titillates taste buds due to its freshness, natural moisture and fats. The healthier the animal the better it cooks because of the fats in its meat.

The meat of the animal that has grazed in the mountains is tastier and softer than the animal that has grazed in the plains. So there is a lot of truth in the statement ‘you are what you eat’.

When a person of some status or more than eight guests arrive at the nomadic household of a Marri tribesman they are offered the meat of goat or sheep. Providing sajji adds to the status of the guest as well as the host.

After the animal is sacrificed all get to work — the guests skin the animal while the hosts bring the wood. Most Marris are expert skinners as goat skins are used for making goat-skin bags (Mashks) and flour-carrying Anbaan from sheepskin.

The meat is put on a ‘chitir’ (chattai) of dwarf palm. It is then vigorously rubbed with salt and skewered on ‘seekhs’ of wood, preferably ‘kalair’, and then struck into the ground. The order in which this is done is important: first the front legs, then the hind legs, the back, ribs and last of all the neck. The liver, fats and other parts are not stuck into the ground but suspended from the last skewer and a stick placed at the very end.

Wood, preferably ‘kaeer’ or ‘kaur’ (types of acacia), is then placed on both sides of the skewered meat and lit simultaneously. Initially, the distance between the meat and fire is about a metre to avoid scorching. As the burning wood turns into embers it is gradually brought closer to provide constant heat. The changing colour of the meat indicates the stage of the roast. When the meat is fully cooked it becomes golden brown in colour.

Music is a part of Marri life and while the sajji roasts, the nari (the reed flute player) and suri (the singer) entertain with music. The suri sings poetry of love, folklore and history.

Round stones, the size of a shot-put, from the dry river bed are placed in the fire to make the ‘kak’. Dough with the consistency of a pizza is kneaded. Then depending on the size of stones the kneaded flour is split up and shaped into thick small bread. Now comes the most difficult part which is not only a test of skill but guts as well because the blazing hot stone is plucked from the fire with bare hands and placed on the dough. The dough is then carefully wrapped around it avoiding the steam emitted from it.

With the dough wrapped around it, it is placed on the embers and slowly rotated to ensure that it is baked on all sides. The inside is baked with the heat of the stone and by the time the sajji is roasted the kak too is ready. A blow on the stone breaks open the kak. The kak is usually made when people are on the move.

It takes about two hours to roast the sajji. It is then carved in a specific manner to make it easy for the guests to partake. There are certain etiquettes which are inviolable and scrupulously observed. The back of the animal is left entirely for the hosts. If a woman from the guests’ family is married into the family of the host then half the rib-cage is set aside for her. At some stage of their history the Bijrani chief and Gazaini chief of these two Marri tribes took a vow that the former would never eat a kidney and the latter would never eat meat left sticking to the ‘seekh’. They still adhere to that vow. The guests may eat as much as they like but they never take the leftovers with them.

The Marri will usually never bite off the meat but will cut it with a knife which most carry. One portion from which meat is never bitten off is the scapula because it is used to foretell the future. The two scapulas complement each other and are never handed over but thrown to the person who wants to read them. Droughts, rains, war, peace and pestilence have been foretold accurately by those who know how to read them.

So sajji is not just food but a way of life with the Marris. Eating hot sajji along with fresh kak on a winter night after a long walk is an unforgettable experience.

SHEER KHURMA, SPECIAL

By Saira Abdullah

Ingredients

4 cups milk 1 cup sugar 1 cup vermicelli ¼ cup almonds, blanched, fried and ground ¼ cup pistachios, fried and ground ¼ tsp saffron 1 tsp cardamom powder 1 tsp oil

Method Cook the milk and sugar. When the milk comes to boil, add the vermicelli and cook for five minutes. Add the rest of the ingredients. Cook for further five minutes. Serve hot or cold with purees.