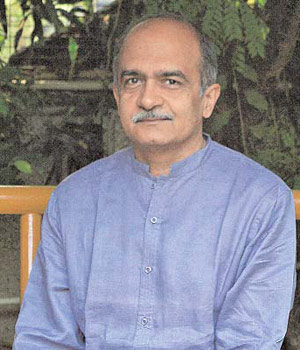

Prashant Bhushan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A profile

Legal activist

Every time a public interest litigation (PIL) shocks the nation, he is behind it. His latest on the CBI chief's alleged illicit meetings with influential persons who were the subject of investigations by the agency has once again caused a huge stir in 2014.

He remains an influential political voice as one of the founders of the Aam Aadmi Party and one of its most articulate leaders.

In an era where top lawyers charge huge appearance fees in court, he spends only about 25 per cent of his time on cases that pay him money. The rest is spent in pro bono work.

Change in track

He went to study engineering at IIT-Madras but left it for a BSc with Economics and Political Science in Allahabad.

A brief biography

As in 2020

From young note-taker in the Emergency case to dogged crusader, Sunday Times charts the career of the activist-lawyer

He has argued for the deprived, he has called out high-stakes corruption, he has dabbled in politics. And today, Prashant Bhushan, lawyer and activist who was found guilty of contempt of court last week, is in the fight of his life.

In 1975, Allahabad, 19-year-old Prashant Bhushan was witness to the greatest courtroom dramas of independent India. As his father Shanti Bhushan fought Raj Narain’s legal challenge to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s election, in the case that eventually triggered the Emergency, Bhushan was furiously scribbling notes. He had a ringside view of the Habeas Corpus and Kesavananda Bharati cases, watershed moments in India’s constitutional history.

That heady time left its impression, as Bhushan was trying to choose a vocation. He had left IIT Madras after a semester — partly because he wanted to study physics, and partly because he missed his baby sister. Then, reading Bertrand Russell set him on another path, eventually taking him to Princeton University for a PhD in philosophy, which he left midway because his interests didn’t mesh with the department. “My father was the most liberal person on earth, he never objected to any decision I made, but he was happy that I joined the law,” says Bhushan.

Shanti Bhushan was one of the most successful lawyers of his time, law minister in Morarji Desai’s cabinet, and a founding member and treasurer of the BJP who soon parted ways with it. But while he has been wholly supported by his father, Prashant Bhushan has walked his own path. “From big environmental law cases to those of corruption and governance, Prashant Bhushan’s career has been instrumental in shaping the character of PILs since the mid-80s,” says legal scholar Anuj Bhuwania.

THE ACTIVIST

He represented the displaced people of Narmada Bachao Andolan to Bhopal gas disaster survivors to those protesting nuclear power in Kudankulam. His Centre for Public Interest Litigation has also taken on causes that others won’t: Enron and Reliance being given the right to develop the Panna-Mukta oilfields, the 2G and coal allocation cases that took on the UPA, or the Sahara diaries. Even today, 80% of his time is taken up by pro bono work. “If what is happening is against the public interest, and I can do something, I should,” says Bhushan, 63. His family wealth frees him to pursue his causes — and to his credit, he has immersed himself in them. Neither careerism or fame seems to be a motive, only a dogged commitment to what he calls justice.

THE LAWYER

Some call his notion of justice simplistic and puritanical. He has not been designated senior advocate in the Supreme Court, despite decades of work and stellar networks — he is, after all, Shanti Bhushan’s son. His outspokenness on corruption, and his face-offs with senior judges have not helped his career. “He has no sense of diplomacy and will not say things to make himself popular,” says his friend and comrade Yogendra Yadav.

In the contempt case of 2009 that is being heard now, he had told Tehelka that eight out of the last 16 Chief Justices were corrupt. But there are those who point out that personal corruption may not be the clinching cause of judgments swinging one way or another. “Corruption doesn’t mean just personal corruption, it can mean improper conduct, or any extraneous considerations,” responds Bhushan. His activism doesn’t make Bhushan wildly popular with his peers either. “He does so many ‘bechara’ petitions, like for migrant workers or slum-dwellers, but the pleadings don’t have much legal rigour. The quality of research and argumentation is often a function of who is briefing him,” says a lawyer. Considering how well-known he is, not many young lawyers are clamouring to work with him either, he points out. “You know how some journalists are admired for their courage, more than their writing? That’s the kind of lawyer Bhushan is, he deserves the Param Vir Chakra, not the Pulitzer,” he says. Some call him conspiracy-minded, say he tends to attribute dark motives without substantiating them. For instance, currently Bhushan seems convinced that Covid has been “overhyped by vested interests, for the commercial advantage of vaccine manufacturers”.

“He can’t go three sentences without calling something a mega-scam. Without doing the homework, when it is based only on a meta-ideological perception of crony capitalism, that can make someone like him a useful tool for judges or even corporate groups who want to take on rivals,” says another lawyer who has often faced off against Bhushan. “After the 2G case, his name is now taken with trepidation. We have mining clients who say, “Tomorrow if Prashant Bhushan files a case, then what? Nobody wants a ‘mega-scam’ attached to their name,” he says.

But for all that, it’s hard to find anyone who doubts Bhushan’s sincerity. Even Harish Salve, a lawyer who has squared off against Bhushan for decades, told TOI in 2011, “every system needs crackpots”, and expresses admiration for his passion and his lawyering.

HIS POLITICS

But apart from words like corruption, justice and public interest, what is Bhushan’s political philosophy?

It is hard to get a measure of the man through his friends and adversaries, or his political stands. He used to have regular lunches with Arun Jaitley in the past, and he has an enduring friendship with Arundhati Roy.

Shaped by Emergency and the anti-Congress activism, he was a leading light of Anna Hazare-led India Against Corruption movement that eventually brought the AAP to power. He had wanted to break with the AAP when it contemplated tying up with the Congress, says Yogendra Yadav. In 2013, he was also quoted as saying that the AAP could extend issue-based support to the BJP.

And yet, today he says his biggest regret is championing a movement “propped up by the BJP-R S S”, and that he was unaware that “Arvind (Kejriwal) was in cahoots with them”. He also says he drifted away from Jaitley for “legitimising Modi-Shah” and that democracy is in worse shape now. “Yes, there was press censorship and people were put in jail, but what is the situation of institutions now? And now there is also violence, lynch mobs on the streets and in social media, degrading critical thinking”. Today, the organisations he worked with, and the groups he advocated for over the decades are rallying behind him. “Bhushan has spoken out against corruption, irrespective of the regime. We need a voice that will say publicly what a lot of people are saying in private,” says activist Harsh Mander, who worked with Bhushan on several cases such as migrant workers, and the Assam detention centres.

The SC’s conviction and Bhushan’s refusal to apologise has even prompted comparisons to Gandhi and Mandela, which he himself was quick to downplay. “The contempt case touched a nerve because so much of the country is feeling choked, unable to speak freely,” he says.

“Anyone who knows Prashant will know he would never apologise for what he said, even if you put a gun to his head. The only way to change his mind is to provide evidence and then he will be the first one to admit he’s wrong,” says Yadav. Bhushan is not worried about the consequences: “Aisa kya hoga? When faced with a difficult situation, look the devil in the eye. They might send me to jail. Fine, my grandparents went to jail during the freedom movement, my father was jailed for a week during the Emergency, so many people go to jail. So will I. I’ll read or write a book, learn about life in prison,” says Bhushan.

Jokes and sci-fi

CHUTKULA MASTER TO FRIENDS

Right after his marriage to Deepa, when he was ‘stranded in Dalhousie for a few months’, he wrote a science fiction novel about a parallel universe that splits off from ours in 1908, and technology that lets people read each other’s minds

“He is a ‘chutkula master’ (joke master) and loves satire by Ashok Chakdradhar and Surender Sharma. In fact, when I met him last to discuss the case he asked me to first listen to a satire by Chakradhar,” says Yogendra Yadav. He has a deep love for art and his collection includes Indian miniatures.

As in 2024 Feb

February 16, 2024: The Times of India

Minutes after Supreme Court struck down electoral bonds, a familiar face was back on national television, explaining the import of the order. SC lawyer and activist Prashant Bhushan is famous for being the last refuge of near-lost causes, whether it is about rations for migrant workers or the choosing of election commissioners, bringing political parties under RTI or taking on powerful businesses.

Speaking to TOI, Bhushan had a measured take on the judgment’s impact: “One swallow does not make a summer. But it is an important and strong judgment that will have adeep impact on the transparency of political funding.” One of the petitioners, Maj Gen (retd) Anil Verma, who leads the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), was more effusive, saying that the order had restored people’s faith in democracy and rule of law. “But while we appreciate this judgment, there are many other issues related to elections that need to be addressed.”

Bhushan’s work in public interest litigation has supported protest groups and environmental causes, taken on high-stakes corruption and matters of governance. “Prashant Bhushan’s career has been instrumental in shaping the character of PILs since the mid-80s,” legal scholar Anuj Bhuwania had told TOIin an earlier interview.

He represented people who banded together to form Narmada Bachao Andolan, Bhopal gas disaster survivors and those protesting nuclear power in Kudankulam. His Centre for Public Interest Litigation has also taken on causes that few would: Enron and Reliance being given the right to develop the PannaMukta oil fields, for instance, the 2G and coal allocation cases, Indo-US nuclear deal that took on UPA, and Sahara diaries that drew in Modi. In 2009, he represented activist Subhash Aggarwal to bring SC and high court judges, including the chief justice of India, under RTI. His firm belief was that people had a right to know details of assets owned by judges.

In 2023 his intervention along with that of petitioners Anjali Bhardwaj, Jagdeep Chhokar and Harsh Mander led SC to direct states to pro- vide ration cards under NFSA to 8 crore workers not covered under the Food Security Act. This ensured food security for migrant workers in the unorganised sector.

Bhardwaj, from the Satark Nagrik Sangathan says, “He has consistently represented progressive move- ments, peoples’ struggles and causes in public interest. His efforts have helped take important matters to courts and bring public attention to issues like migrant workers’ rights and vacancies in information commissions.”

But Bhushan’s pivot towards politics left him disenchanted. In the 2010-2015 period, he started with joining the Anna movement and was founder-member of AAP. He left AAP. And once a big target of his attacks, Congress is now Bhushan’s pick as an alternative to the present political dispensation. In recent times he has expressed confidence in Congress leader Rahul Gandhi.

But he also has a penchant for courting controversy: from tweeting about a sitting CJI’s “corruption” to publicly dissing masks and vaccines during Covid as a govt conspiracy. He has long supported the view that EVMs are manipulable and has approached courts for a comprehensive probe on the issue. After voicing his views on a plebiscite in Kashmir, he was assaulted by right- wing vigilantes.

In 2020 he was charged for defamation but got off with a Re 1 fine. Speaking ahead of the verdict on the possibility of a prison sentence in 2020 he told TOI, “Aisa kya hoga? When faced with a difficult situation, look the devil in the eye. I can handle all the possibilities. They might ban me from court for a year, or suspend my Twitter account, or send me to jail for six months. Fine, my grandparents went to jail during the freedom movement, my father was jailed for a week during the Emergency, so many people go to jail. So will I, I’ll read or write a book, learn about life in prison”.

Perhaps these seeds of rebellion were sown early. A young Bhushan had a ringside view of the Raj Narain vs state of UP, habeas corpus and Kesavananda Bharti cases, watershed moments in India’s constitutional history, thanks to his father Shanti Bhushan’s legal career. Shanti Bhushan was one of the most successful commercial lawyers of his time, law minister in Morarji Desai’s cabinet, and a founding member and treasurer of BJP, which he left quickly. But while he has been wholly supported by his father, Prashant Bhushan has walked his own path, using his privilege and legal abilities to fight cases in what he insists are public interest matters.

At 67, Bhushan is ready for more. When asked if he was considering hanging up his boots, he says, “Nahi, abhi nahi. Jab tak jaan hai…I want to keep going.”