Monsoons: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

In three sentences

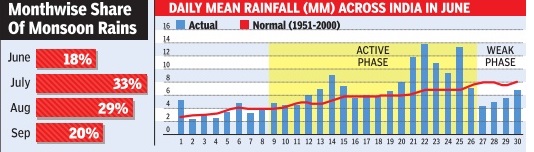

The four-month monsoon [rainy] season normally begins from June 1 and ends on September 30. The Southwest Monsoon gives 70 per cent (of the entire year's) rains to the country, where agriculture still remains a major contributor to the GDP. June contributes 17% of the total rainfall, July 32%, August 28% and September 23%. (From PTI)

And three more sentences:

How long was the monsoon break in June, during the period 2010 to 2018?

2010: It was a 13-day break, the longest in June in the years 2010-18

2018: The monsoon did not move for 9 days after June 13.

A backgrounder

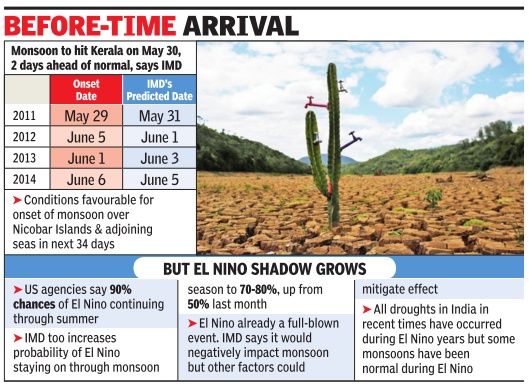

Monsoon usually reaches India's mainland by first week of June, May 29 2017: The Times of India

What causes monsoon?

Monsoon, which is the seasonal reversal in the wind direction, causes most of the rainfall received in India and some other parts of the world. The primary cause of monsoons is the difference between annual temperature trends over land and sea. The apparent position of Sun with reference to earth is not fixed -it oscillates from tropic of cancer to Capricorn through the equator. The heating leads to the creation of a low pressure region. The northeast and southeast trade winds converge in this low pressure zone which is also known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). This low pressure region witnesses continuous rise of the moist wind from the sea surface to the upper layers of atmosphere, where the cooling causes the loss of moisture resulting into precipitation. It is observed that the rainy season of east Asia, Sub Saharan Africa, Australia and southern parts of North America coincides with the shift of the ITCZ towards these regions.

What causes Indian monsoon?

Thar Desert and adjoining areas of the northern and central Indian Subcontinent heats up during the hot seasons of sum mer. Because of the rapid solar heating mainly between April and May a lowpressure cell is created over the Indian subcontinent. To fill up this void, the moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean rush in to the subcontinent. The ITCZ, which is sometimes also referred as monsoon trough also shifts northwards towards the subcontinent causing monsoon rains which typically reaches subcontinent's mainland in the last week of May or the first week of June. The metdepartment declares the onset of monsoon over Kerala if 60% of the 14 enlisted stations falling in the states report a rainfall of 2.5mm or more for any two consec ll of 2.5mm or more for any two consec utive days falling after 10 May.

What are the ways to forecast monsoon?

Generally there are three main approaches used for long range forecast of the southwest monsoon in India. The first is the statistical method which uses the historical relationships between southwest monsoon and various global weath er parameters. The historical data is then used to forecast the onset of the monsoon.The second approach is the empirical method which uses time series analysis of past rainfall data. The third is the dynamical method which uses general circula tion models of atmosphere and oceans to predict the southwest monsoons. It is observed that the prediction models based on statistical approach have so far yielded most accurate results for the Indian monsoon. However none of the models can claim 100% accuracy because there are several factors like the correlations between the parameters, changing predictability of the model over a period of time.

Which method is used by our met-department to forecast monsoon?

Prior to 2002 IMD used to issue annual forecast using a model based on 16 parameter but it failed in 2002. Since 2003 two new models were introduced which instead of 16 used 8 and 10 parameters to forecast the southwest monsoon in India. Apart from this a two stage forecast system was also introduced--the first stage forecast was issued in mid April and an update or second stage by the end of June. This model also gave false predictions for 2004. Since 2007 a new forecast system using ensemble technique is being used to forecast monsoon. At present monsoon is predicted on the basis of five predictors including the sea surface temperature (SST) gradient between north Atlantic and north Pacific, Equatorial South Indian Ocean SST, East Asia Mean Sea Level Pressure, Northwest Europe Land Surface Air Temperature and Equatorial Pacific Warm Water Volume at designated times of the year. Instead of relying on one model with best possible forecast, the ensemble method uses inputs from the forecast of all models to calculate the final result.

Factors that influence the monsoons

Dust, soot from West Asia affect monsoon in India

Summary

Dust & soot from West Asia affect monsoon in India, November 16, 2018: The Times of India

Dust and soot transported from the deserts of the Middle East settle on the snow cover of the Himalaya mountain range and affect the intensity of the summer monsoon in India, a study has found.

Using a powerful Nasadeveloped atmospheric model, researchers from University of Maryland in the US found that large quantities of dark aerosols — airborne particles such as dust and soot that absorb sunlight — settle on top of the Tibetan Plateau’s snowpack in spring before the monsoons begin.

These dark aerosols cause the snow to absorb more sunlight and melt more quickly. The findings suggest that, among these dark aerosols, windblown dust from the Middle East has the most powerful snow-darkening effect.

In years with heavy springtime dust deposition, the end result is reduced snow cover across the Tibetan Plateau, which leads to warmer temperatures on the ground and in the air above it.

Hundreds of studies have supported this relationship since British meteorologist Henry Blanford noted a connection between springtime Himalaya snow cover and the intensity of Indian monsoons. However, they have struggled to explain the reason for the same.

Researchers used the Goddard Earth Observing System Model to simulate 100 years’ worth of springtime snow cover and its influence on the yearly summer monsoon cycle. To test the effect of dust blown in from the Middle East, the researchers ran the same simulations again, with an added software package that incorporates the snowdarkening effects of dark aerosols deposited atop the Tibetan Plateau.

Adding dark aerosol deposition to the model substantially increased the amount of sunlight absorbed by the snow, accelerating the rate of melting. This is because when snow melts, it begins to expose the darker ground underneath, which absorbs even more sunlight and intensifies the rate of melting.

Researchers also found that the strongest effect in cycles when a large amount of dust settled on the snowpack in April, May and June.

Details

November 14, 2018: Science Daily

Source: University of Maryland

Middle Eastern desert dust on the Tibetan plateau could affect the Indian summer monsoon: New atmospheric modeling study could explain the mechanism behind a century-old hypothesis

New research led by William Lau, a research scientist at the University of Maryland's Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center (ESSIC), provides a plausible mechanism to explain Blanford's observations. Surprisingly, the explanation involves dust transported from the deserts of the Middle East, more than a thousand miles away.

Using a powerful NASA-developed atmospheric model, Lau found that large quantities of dark aerosols -- airborne particles such as dust and soot that absorb sunlight -- settle on top of the Tibetan Plateau's snowpack in spring before the monsoons begin. These dark aerosols cause the snow to absorb more sunlight and melt more quickly. The model findings suggest that, among these dark aerosols, windblown dust from the Middle East has the most powerful snow-darkening effect.

In years with heavy springtime dust deposition, the end result is reduced snow cover across the Tibetan Plateau, which leads to warmer temperatures on the ground and in the air above it. This in turn sets off a series of interconnected feedback loops that intensify India's summer monsoon. A paper describing the research, co-authored by Kyu-Myung Kim of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, was published online November 12, 2018 in the journal Atmosphere.

"Blanford knew that snow cover on the Tibetan Plateau wasn't the only phenomenon that influenced the monsoon, but he knew it was important," Lau said. "The relationship between snow cover and the monsoon is useful enough that the India Meteorological Department still uses it to develop its annual summer monsoon forecast. By adding knowledge of the physical mechanism responsible for this relationship, our study may help to develop more accurate monsoon forecasts."

Lau and Kim used the Goddard Earth Observing System Model, Version 5 (GEOS-5) to simulate 100 years' worth of springtime snow cover and its influence on the yearly summer monsoon cycle. To test the effect of dust blown in from the Middle East, the researchers ran the same simulations again, with an added software package that incorporates the snow-darkening effects of dust, soot and other dark aerosols deposited atop the Tibetan Plateau.

Adding dark aerosol deposition to the model substantially increased the amount of sunlight absorbed by the snow, accelerating the rate of melting. This is because when snow melts, it begins to expose the darker ground underneath, which absorbs even more sunlight and intensifies the rate of melting.

In addition to darkening the snow early in the season, the dust also strongly enhanced atmospheric warming of the Tibetan Plateau, leading to changes in wind patterns that intensify the peak monsoon. Notably, this series of feedbacks also strengthened the same winds that transport dust from the Middle Eastern deserts, bringing more dust and further enhancing the feedback loop.

According to Lau, many researchers contend that heavy monsoon rains should wash any airborne dust particles from the air, canceling out the dust's atmospheric heating effects and shutting down the feedback loop. But Lau and Kim's results suggest that enhanced winds transport enough dust to overwhelm this washout effect, leading to a net accumulation of dust on the Tibetan Plateau.

The timing of the dust's arrival was also important. Lau and Kim found the strongest effect in cycles when a large amount of dust settled on the snowpack in April, May and June.

"Every year was different in the model results. When dust arrived early in the season, it set up the initial conditions needed to change the monsoon dynamics," Lau said. "But in some years, late-season snowstorms at high altitudes covered the dust and shut down the feedback loop. It's very clear that there is a relationship between snow darkening by aerosols -- particularly Middle Eastern desert dust -- and the Indian monsoon season."

Lau and Kim acknowledge the need to move beyond modeling and investigate the connections between dark aerosols, heating and the monsoon cycle using other methods and new observations. But they are confident that their results -- which used real-world data to seed the GEOS-5 model -- could help inform monsoon prediction efforts now.

"This could be extremely important for agriculture. Farmers have to plan around the monsoon season to decide when to plant and when to harvest," Lau said. "In order to understand how human influences like climate change and land use affect the monsoon, we have to understand the basics -- including the effects of light-absorbing aerosols in darkening the snow on the Tibetan Plateau and in modulating the Asian summer monsoon. Such effects are so important that in the end, we may have to rewrite the curriculum for 'Monsoon 101.'"

Materials provided by University of Maryland. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

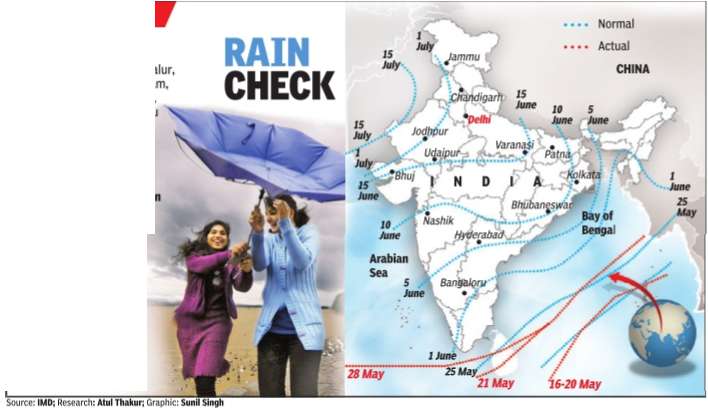

Criteria used in deciding whether monsoon has arrived

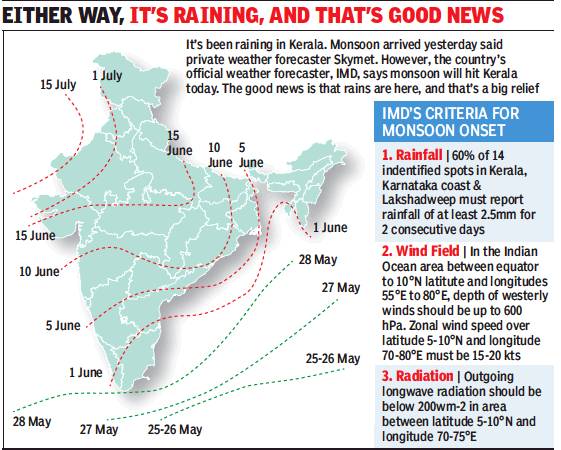

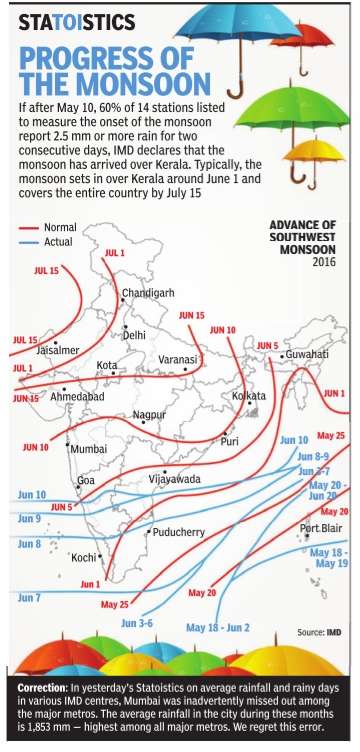

i) The criteria that IMD adopts to decide whether monsoon has arrived or not.

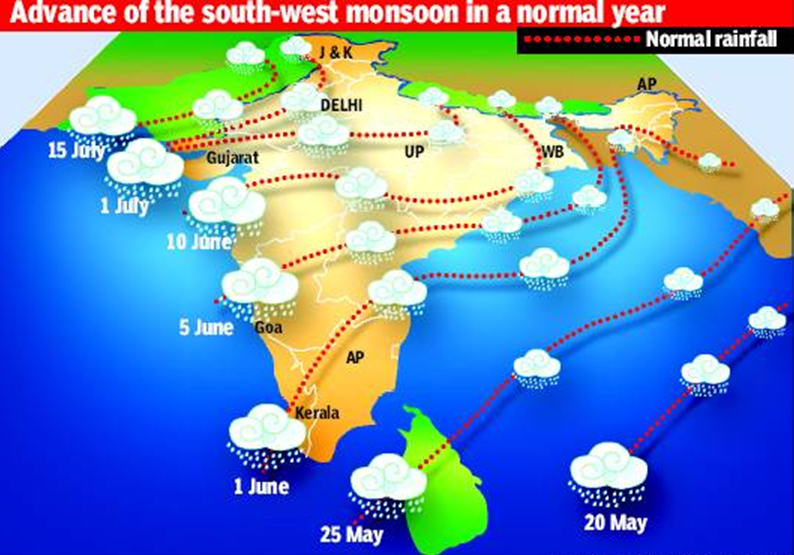

ii)The dates on which the monsoon normally reaches various parts of India. From The Times of India

See graphic, ' i) The criteria that IMD adopts to decide whether monsoon has arrived or not.

ii)The dates on which the monsoon normally reaches various parts of India. ',

The amount of rainfall

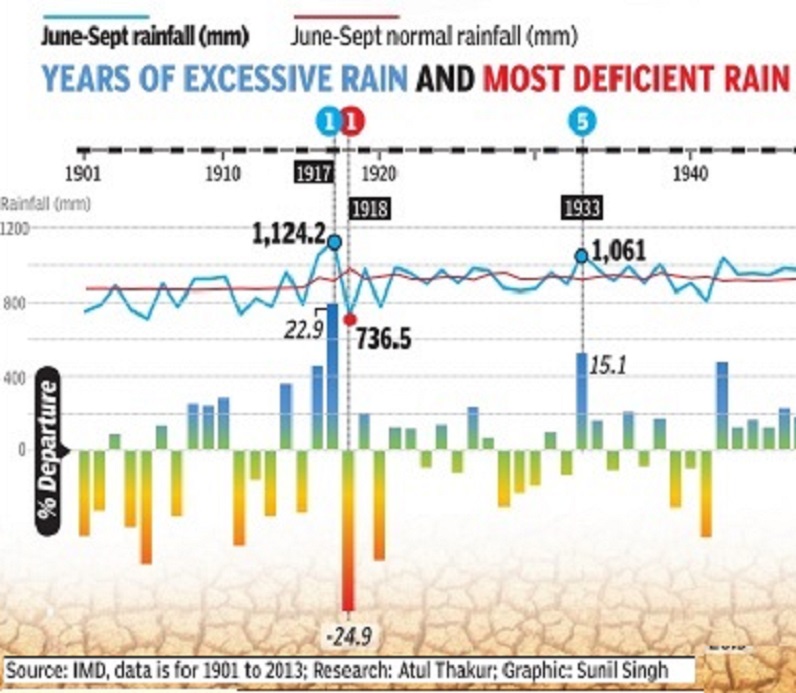

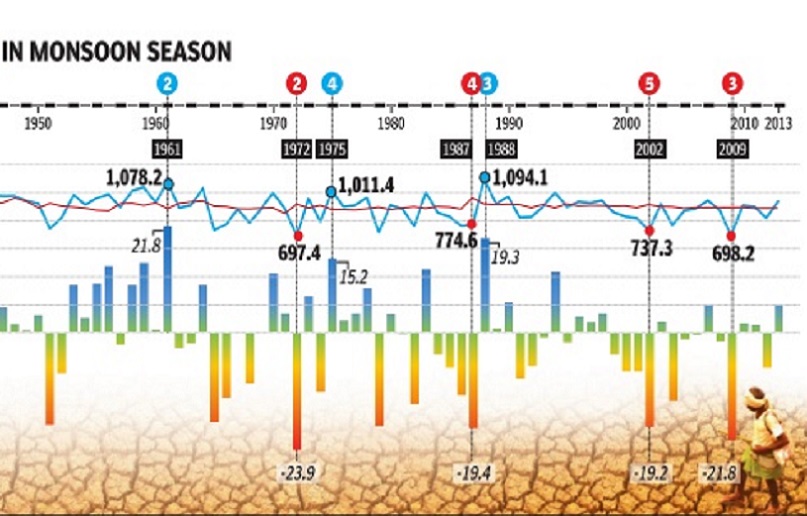

1901-2013: Monsoons that crossed the 100% mark

See graphics, '| Years of excessive rain and most deficient rain in monsoon season, 1901-2013 '

Since 1901, there have been 59 years when the monsoon has crossed 100% of the LPA. Since 2000, there have been only four years when monsoon crossed the 100% mark. These are 2003, 2007, 2010 and 2011. The projection is welcome news for the government as a stuttering monsoon can cast a long shadow on its political fortunes with growth slipping below 5% and high food inflation — prices for consumers rose 11.84% in June — proving a sizeable thorn in the side for UPA-2.

The government hopes the farm sector significantly improves on 2012’s 1.8% growth with R Rangarajan, chairman of the PM’s economic advisory council, saying a normal monsoon could even yield a 3.4% growth.

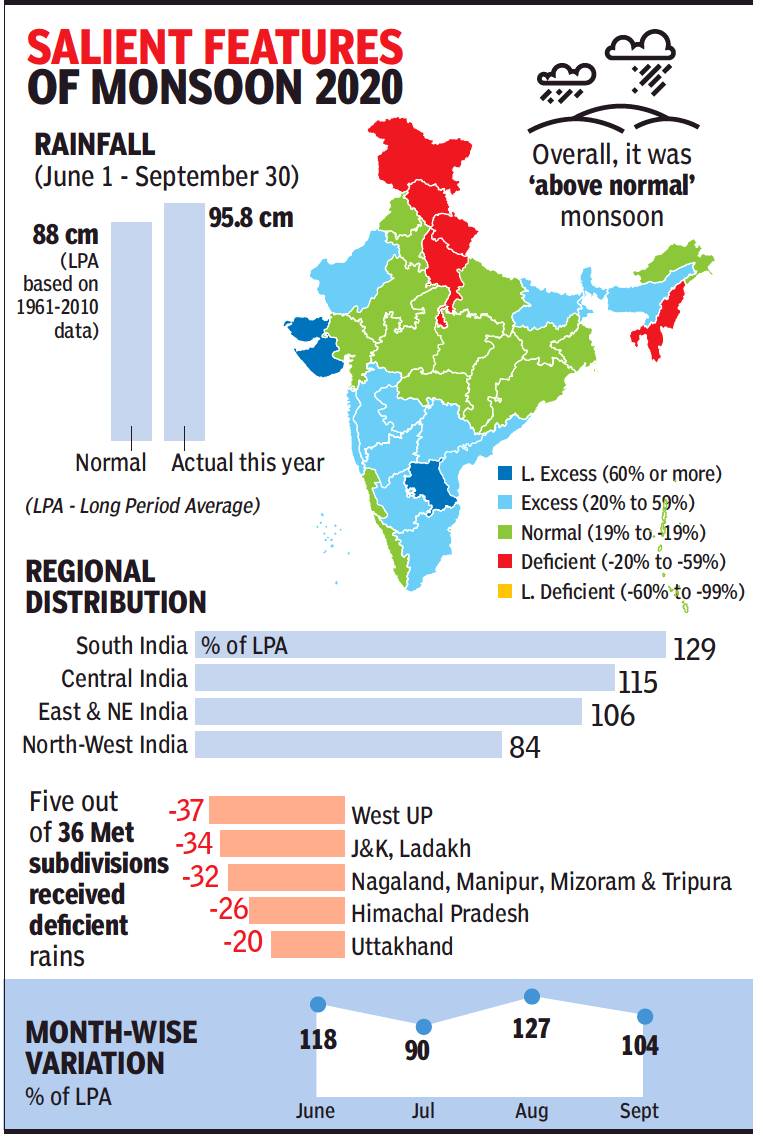

India: Back-to-back, ‘above normal’ monsoon after 1958-59

From: After 61 yrs, India gets back-to-back ‘above normal’ monsoon seasons, October 2, 2020: The Times of India

For the first time in 61 years, India recorded back-to-back “above normal” monsoon years, with this year’s season ending with countrywide rainfall at 9% above the long period average (LPA). Monsoon rains this year were also the second highest in 26 years after 2019, when rainfall across the country was 10% above the LPA.

The last time India had two consecutive years of above normal monsoon was in 1958 (110% of LPA) and 1959 (114% of LPA). This year, an average of 95.8cm of rain was recorded in the country as against the LPA of 88cm.

Surplus rains in June, Aug & Sept

However, the distribution of seasonal rainfall during the June-September period was not uniform. The country recorded the highest 127% of LPA rainfall in August while July was a deficit month with 90% of LPA. The monsoon rainfall has to be between 96%-104% of LPA to be considered “normal” and between 104-110% of the LPA to be described as “above normal”. Anything more is termed “excess” rainfall.

In its first stage forecast for the seasonal rainfall issued in April, the IMD had predicted rains to be 100% of LPA (normal) with a model error of ± 5%. The forecast was upgraded to 102% of LPA, with a model error of ± 4%, in IMD’s update in May end. IMD also predicted a probability of 65% of monsoon rainfall to be “normal” to “above normal”. The actual seasonal rainfall for the country as a whole was 109% of LPA, which is more than the predicted value and thus turned out to be positive for the kharif (summer) crops.

Though India had recorded deficit rainfall in July, the surplus rains in June, August and September helped in the country recording an all-time high acreage. Based on it, the agriculture ministry has set a record target of 301 million tonnes of foodgrains for the 2020-21 crop year. The monsoon started retreating from western parts of north-west India on September 28 against the normal withdrawal date of September 17. As on Thursday, the south-west monsoon had withdrawn from Punjab, western Himalayan region, Haryana, Chandigarh, Delhi and parts of Rajasthan and some parts of Uttar Pradesh.

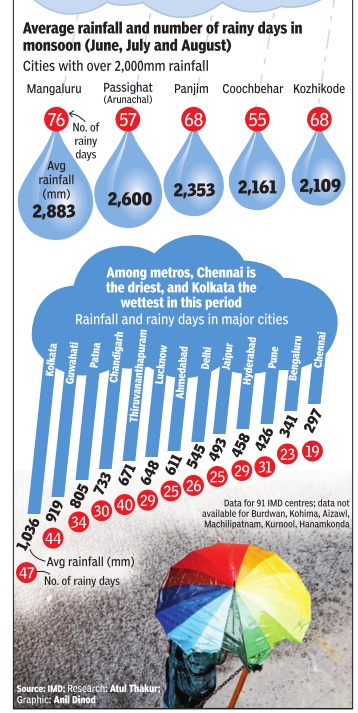

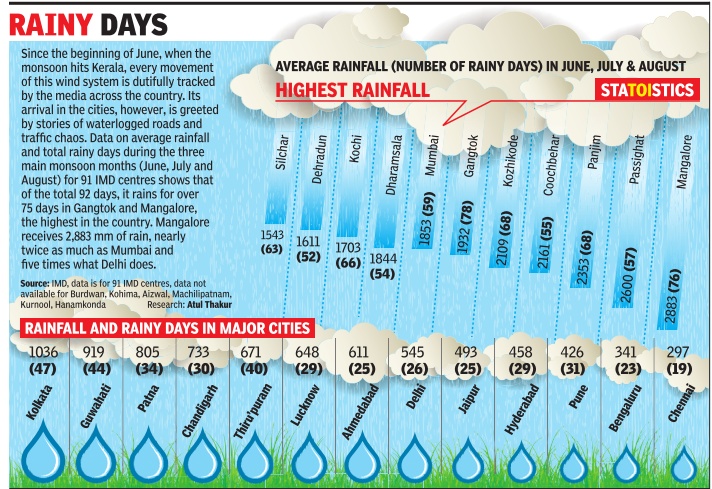

Driest, wettest cities of India: Jun-Aug

See graphic, ' The driest and wettest cities of India during the monsoons '

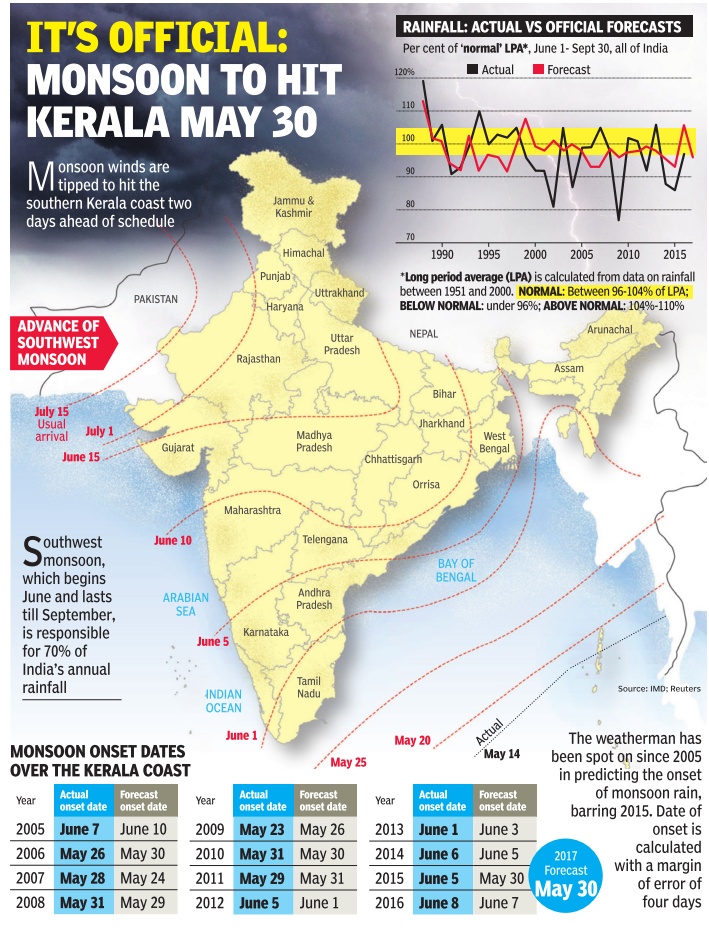

Dates when monsoons reach different regions

In typical years

See graphic, ' The dates on which the monsoon normally reaches various parts of India. '

Years in which the monsoon arrived early

See graphic, ' Years in which the monsoon arrived early: 2011-2014'

Kerala, 2005-2017: actual dates

ii) Actual rainfall vis-à-vis official forecasts, 1990-2015;

iii) The dates on which the monsoon normally reaches various parts of India. The Times of India, May 17, 2017

Delhi: 2007-12

See accompanying chart for Delhi The arrival of the monsoon in Delhi: 2007-12

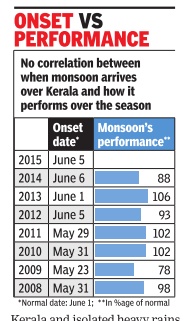

Kerala: 2008-15, onset vs performance

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic, ' Date of onset of Monsoons in Kerala, 2008-15, vis-à-vis its all- India performance. There is no correlation between early or late arrival in Kerala and good or bad all- India performance'

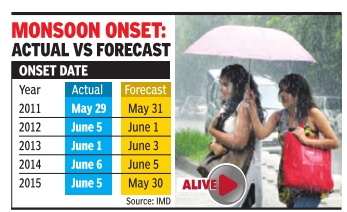

2011-15: actual and forecast dates

See graphic, ' Onset date for Monsoons, actual and forecast, 2011-15, year-wise '

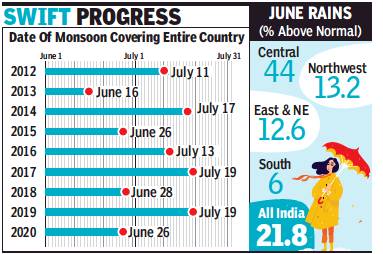

2012-20: Date of Monsoon covering entire country

Monsoon covers India 12 days in advance, fastest since 2013, June 27, 2020: The Times of India

From: Monsoon covers India 12 days in advance, fastest since 2013, June 27, 2020: The Times of India

22% Rain Surplus In June, Good Sign For Sowing

Pune/New Delhi:

In a swift and smooth advance through the country, the monsoon covered the whole of India, 12 days before the normal date of July 8, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) said.

Along with 2015, when the monsoon had raced through the country on the same date, this was the fastest progression of the rain-bearing system since 2013.

In the past 13 years, the monsoon has covered the entire country before June 26 only once — in 2013, when a freak convergence of several weather systems had caused the catastrophic Kedarnath deluge while advancing the monsoon by an all-time record date of June 16.

IMD said the monsoon marched into the remaining parts of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan to cover the entire country, 26 days after hitting the Kerala coast. This sets the stage for timely sowing of kharif crops across the country.

“This was one of the smoothest advances of the monsoon in recent years. Usually the monsoon progresses in fits and starts, but this year it did not stall for long at any stage,” said D Sivananda Pai, IMD’s lead monsoon forecaster.

2020: 2 weeks early

Monsoon covers entire country nearly two weeks early: IMD, June 26, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: The Southwest Monsoon has covered the entire country nearly two weeks ahead of its schedule, the India Meteorological Department said.

The monsoon usually sets over Kerala on June 1 and it takes 45 days to reach Sriganganagar in west Rajasthan, its last outpost in the country.

From this year however, the IMD has advanced the onset date over Sriganganagar by a week and the new normal date for monsoon to cover the entire country is July 8.

"The Southwest Monsoon has further advanced into the remaining parts of Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab and thus it has covered the entire country today, June 26," the IMD said.

A low-pressure area over the Bay of Bengal, which moved west-northwestwards, and another cyclonic circulation over central India helped in advance of the monsoon.

In 2013, the monsoon had covered the entire country on June 16. This had also coincided with the deadly Uttarakhand flash floods.

"After 2013, monsoon has covered the country so rapidly this year," IMD Director General Mrutunjay Mohapatra said.

Monsoon cycle

The Times of India , Jun 02 2015

If after May 10, 60% of 14 stations -Minicoy, Amini, Thiruvananthapuram, Punalur, Kollam, Allapuzha, Kottayam, Kochi, Thrissur, Kozhikode, Thalassery, Kannur, Kudulu and Mangalore -report rainfall of 2.5 mm or more for two consecutive days, the onset of the monsoon is declared on the second day. Normally, the monsoon sets in over Kerala around June 1 and then advances northwards. By June 5, it goes past half of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh and crosses Maharashtra by the 10th.It covers significant portions of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh by June 15 and the entire country by June-end.

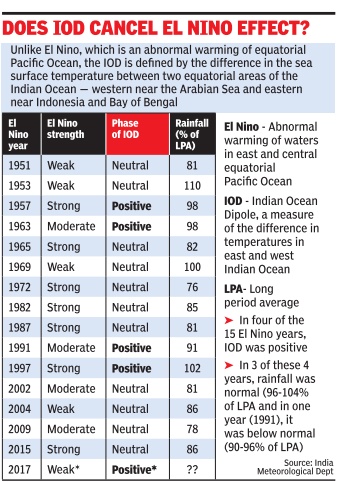

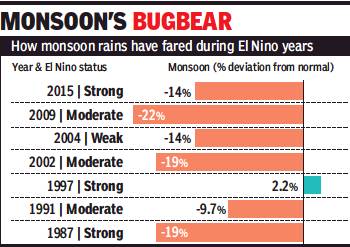

The El Niño effect

1951-2017: El Niño Vs. IOD

See graphic:

Impact of the El-Nino on Indian monsoons, 1951-2017

1970-2015

From: Amit Bhattacharya, Does IMD forecast signal monsoon acing El Nino in ’19?, April 17, 2019: The Times of India

IMD has forecast a “near normal” monsoon this year while also indicating that a weak El Nino is likely to persist through the rainy season. If both forecasts hold true, it would be only the second time in nearly 50 years that India will have a normal monsoon in an El Nino year.

There have been nine El Nino years since 1970, and only once has the Indian summer monsoon remained unscathed from its influence. That was in 1997, when despite one of the strongest El Ninos, the monsoon ended 2% above normal.

In the other eight instances, the June-September rains in India were hit irrespective of El Nino’s strength — weak, moderate or strong — indicating a strong link between the weather anomaly in the Pacific and monsoon’s performance in India.

El Nino is an abnormal warming of ocean waters in east and central equatorial Pacific that drives changes in wind currents which, in turn, have weather impact around the world.

Apart from 1997, other instances of good monsoons during El Nino years are all from the 1950s and 60s. “There are two years when the monsoon was normal or above normal during a weak El Nino, 1953 and 1969. This year’s El Nino is also predicted to be weak,” said D Sivananda Pai, IMD’s lead monsoon forcaster. The monsoon also defied El Nino in 1957 and 1963, IMD records show.

However, the link between El Nino and poor monsoon appears to have strengthened in recent decades. All four El Ninos since year 2000 have adversely impacted rainfall in India. This includes a weak episode in 2004, which led to a drought year with the monsoon ending at 14% below normal.

In recent years, just a warming in the Pacific, which didn’t result in an El Nino, is believed to have impacted the monsoon in 2012 and 2014. However, every El Nino is unique with its own peculiarities. How it plays out, and whether large-scale features that depress the monsoon actually develop, remains to be seen.

How the monsoons control our destiny

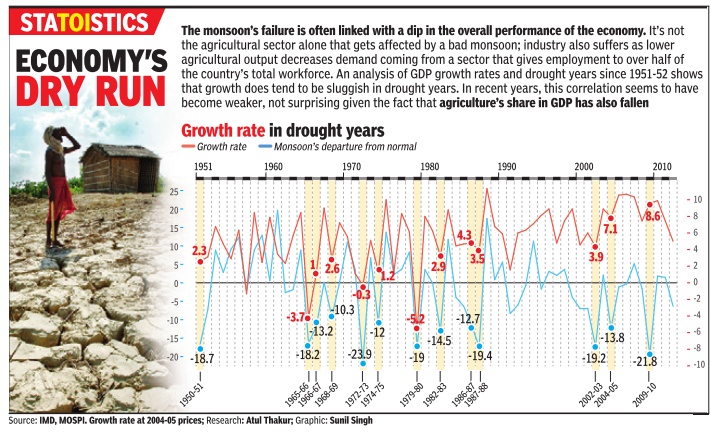

1950-2010: India’s growth rate in drought years

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic ‘Growth rate in drought years in India and monsoon departure from normal’

Why Monsoon Matters Beyond The Farm

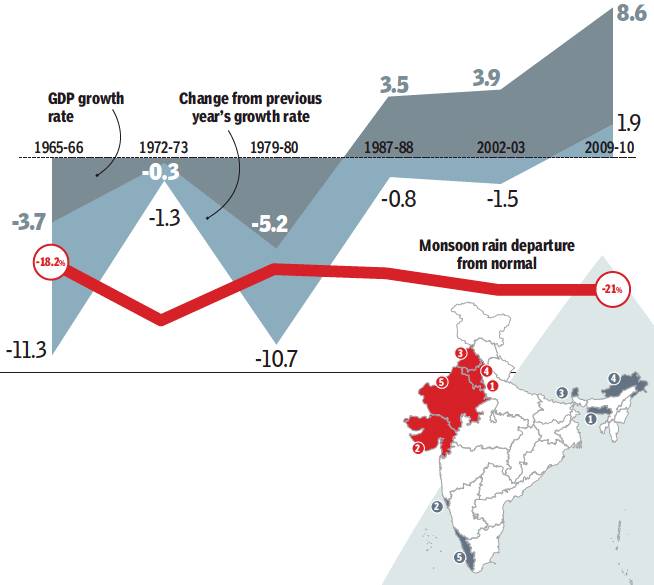

1965-2010

June 11, 2018: The Times of India

GDP growth rate;

Change from previous year's growth rate'

1965-2010

From: June 11, 2018: The Times of India

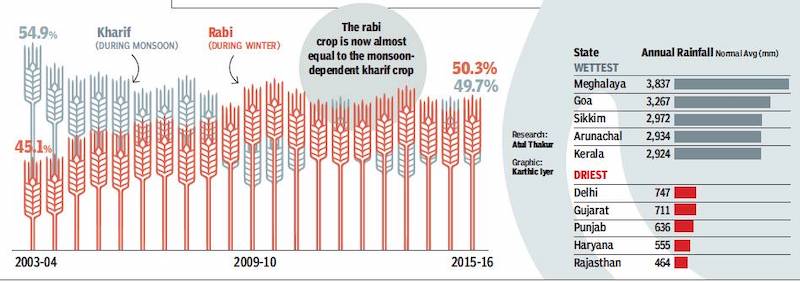

annual rainfall, state-wise

From: June 11, 2018: The Times of India

Amid hopes that the projected 97% monsoon will fuel growth, here’s a look at monsoon’s role in India’s economy

How does the monsoon affect India’s economy?

The monsoon’s failure is often linked to the economy’s overall performance. It is not the agricultural sector alone that is affected by a bad monsoon — industry too suffers as lower farm output decreases demand from this sector, which employs half the country’s workforce. Contrasting GDP growth rates with drought years since 1951-52 reveals growth is sluggish in drought years. In recent years this correlation has become weaker, which may be linked to the fact that agriculture’s share in GDP has also fallen. But it continues to employ half of India’s workforce.

Is there a major difference between agricultural output in Kharif and Rabi seasons?

Over the past decade, the share of Kharif (monsoon) crops in the national output have fallen, while Rabi (winter) crops are on the rise. Crops like rice and maize, which grow in monsoon and winter, have seen a marked decline in Kharif output, while the share of their Rabi output has risen. Exclusively Rabi crops, such as wheat, remain unaffected by monsoons.

What is the Indian monsoon?

The southwest monsoon is a summertime reversal in wind direction that provides nearly 70% of the Indian subcontinent’s annual rainfall. Monsoon winds originate from the southern Indian Ocean. They get deflected southwestwards towards India after crossing the equator. These winds are driven by air pressure differences caused by the more rapid heating up of the land in summers compared to the ocean. The land heats up the air over it, causing it to rise and create a low-pressure zone, which attracts winds from the highpressure regions over the ocean. In south Asia, the effect is enhanced by the Tibetan plateau, which heats up more than the atmosphere would at its height. Monsoon has a set pattern of advance and withdrawal. It arrives in southern India in May or June, and advances northwards and westwards, reaching Pakistan by July. It retreats from Pakistan by September, finally withdrawing from southern India by December. The season doesn’t see a continuous deluge, but has alternate wet and dry phases, the timing and duration of which account for much of the year-to-year variation in monsoon rains.

What are the country’s wettest and driest states?

Mawsynram, a village in Meghalaya is the world’s wettest place. Meghalaya receives the country’s highest rainfall followed by Goa and Sikkim. The national capital on the other hand was among the driest states in 2016.

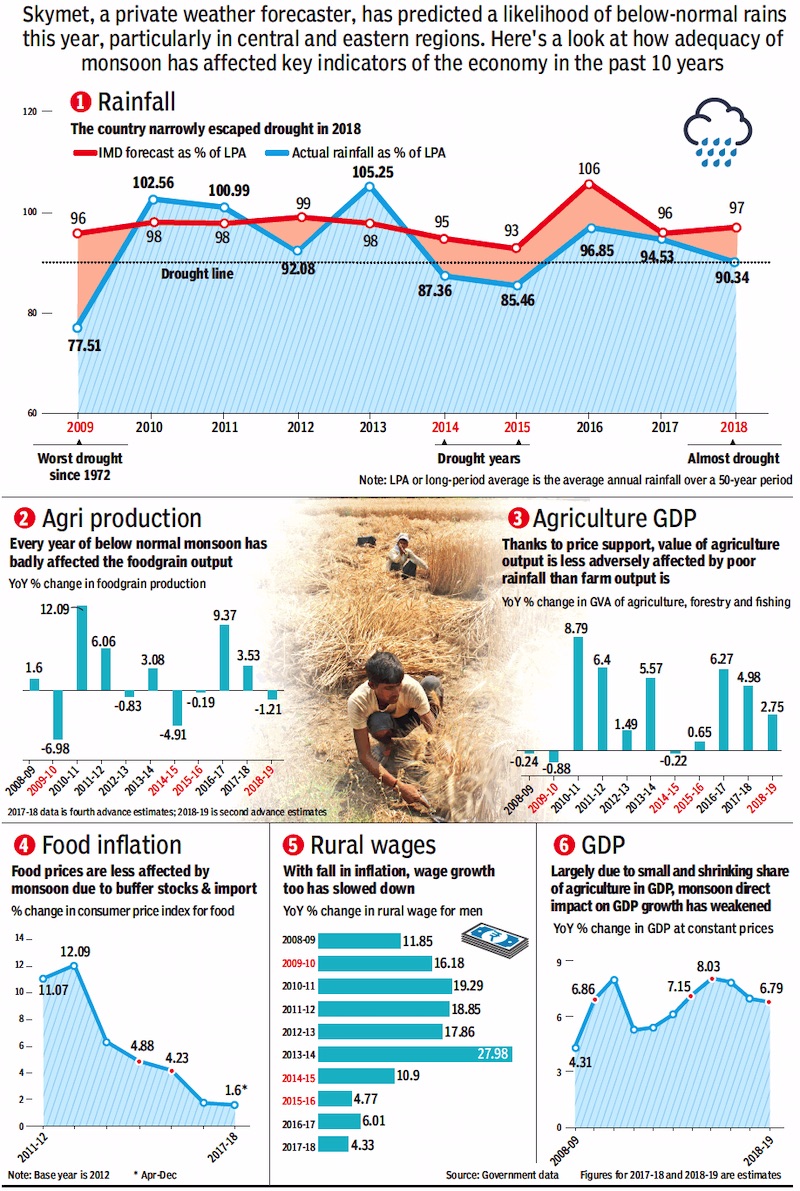

2008-19

April 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: April 5, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

How monsoon affects our lives in India, 2008-19

Skymet, a private weather forecaster, has predicted the likelihood of below-normal rains this year, particularly in the central and eastern regions. The forecaster pegged rainfall in the country during the 2019 monsoon (June-September) at 93% of the long-period average (LPA) of 887 mm. LPA is defined as the average annual rainfall over a 50-year period. There is a a 55% probability that the total rainfall will be below normal and a 15% probability of drought.

What is a normal monsoon

India defines average, or normal rainfall as between 96-104% of a 50-year average of 89 cm for the entire four-month season beginning June until September. Anything less than 90% is a 'deficient' monsoon, while 90-96% is considered 'below normal'. An average between 104-110% is 'above normal' and anything above 110% is 'excess'. Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), the country's official weather forecaster, will issue its monsoon outlook later this month. A good monsoon which waters more than half of the country's farmland is essential to boost consumption and economy. Even though farming output makes up just less than 14% of India's economy, the sector employs more than half of the country's 1.3 billion population. Here's a look at how the adequacy of monsoons has affected key indicators of the economy in the past 10 years.

1. RAINFALL

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

The country narrowly escaped a drought in 2018, following two successive years of normal rains. Skymet's forecast of a below normal monsoon in 2019 is on account of a developing El Nino phenomenon, when warm waters in the Pacific Ocean impact summer rains in India. "The Pacific Ocean has become strongly warmer than average. This means, it is going to be a devolving El Nino year," said Jatin Singh, Skymet's managing director. "But even if it is a mild El Nino, it will have its impact on rainfall," added GP Sharma, Skymet's president of meteorology.

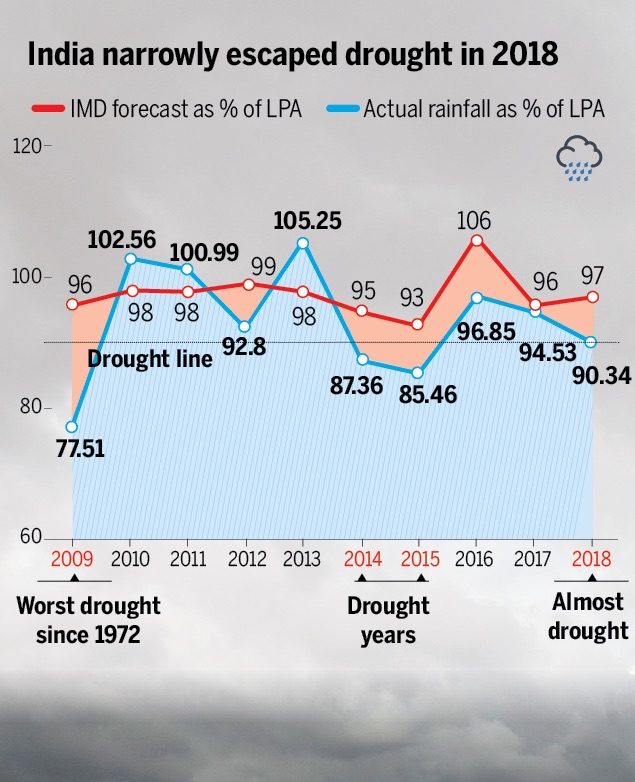

2. AGRICULTURE PRODUCTION

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

The monsoon delivers about 70% of India's annual rainfall and is key to the success of the agriculture sector, There is a 75% probability of below normal rainfall this June, which could decrease to 55% in July, the two months when rains are critical for the sowing of kharif (summer) crops. The monsoon is then likely to pick up pace in August and September, during which El Nino will begin to decay. Every year of below-normal monsoon badly affects foodgrain output. Farm output suffers majorly in a drought year, when rainfall is more than 10% below normal, like in 2014-15 and 2015-16. Both years -- the first two of PM Narendra Modi's tenure -- saw negative growth in farm production, but recovered substantially in the 2016-17.

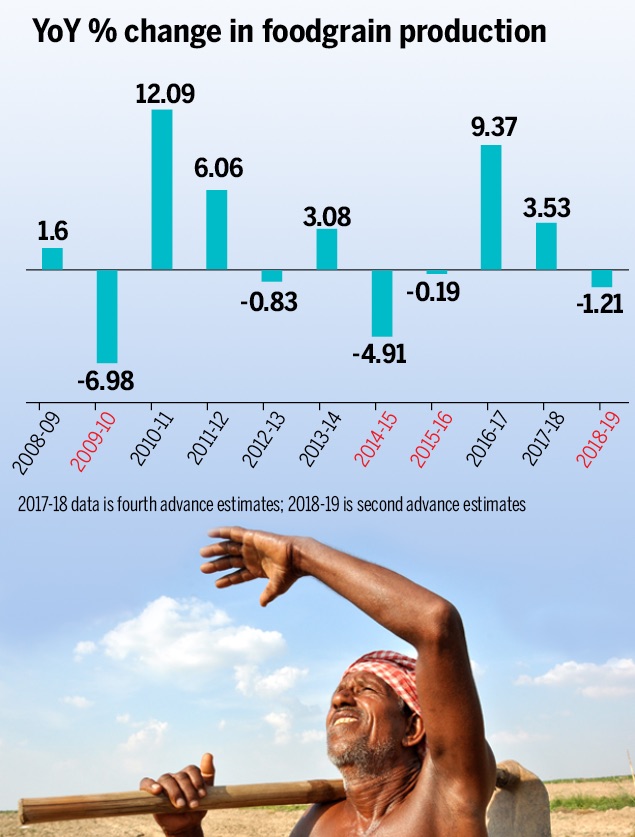

3. AGRICULTURE GDP

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

Thanks to price support, the Gross Value Added (GVA) of agriculture output is less adversely affected by poor rainfall than farm output is.

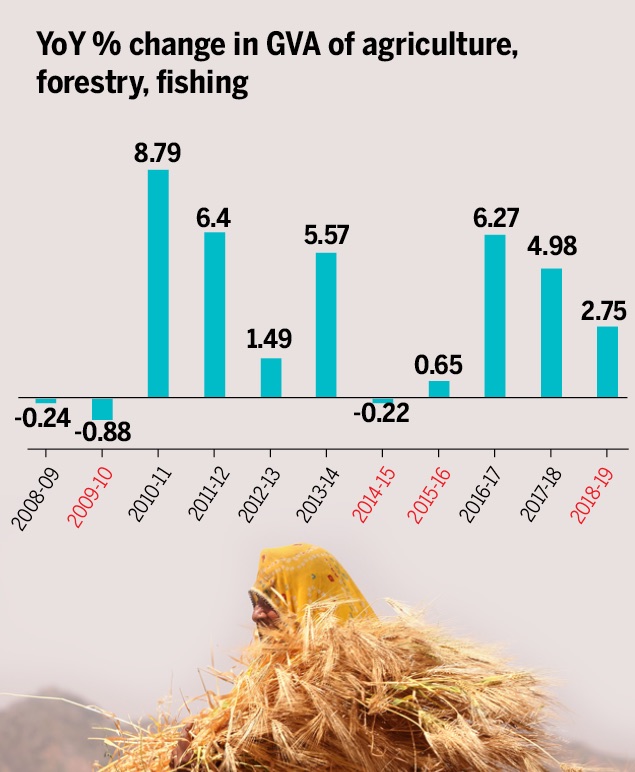

4. FOOD INFLATION

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

Food prices are less affected by monsoon due to buffer stocks and import. Other factors that drive food inflation in India -- rural wages, minimum support prices (MSP), agriculture input costs and global food prices.

First, rural wages are important because human labour accounts for 25-20% of the total cost of cultivation of crops such as rice and wheat. Second, MSP directly feeds into food inflation by forming a floor for wholesale food prices. Third, agriculture input costs such as electricity, diesel, pesticides and machinery also impact food inflation. Fourth, global food prices are important because of their influence on products that India imports and because international prices are one of the factors used to determine the MSPs of crops.

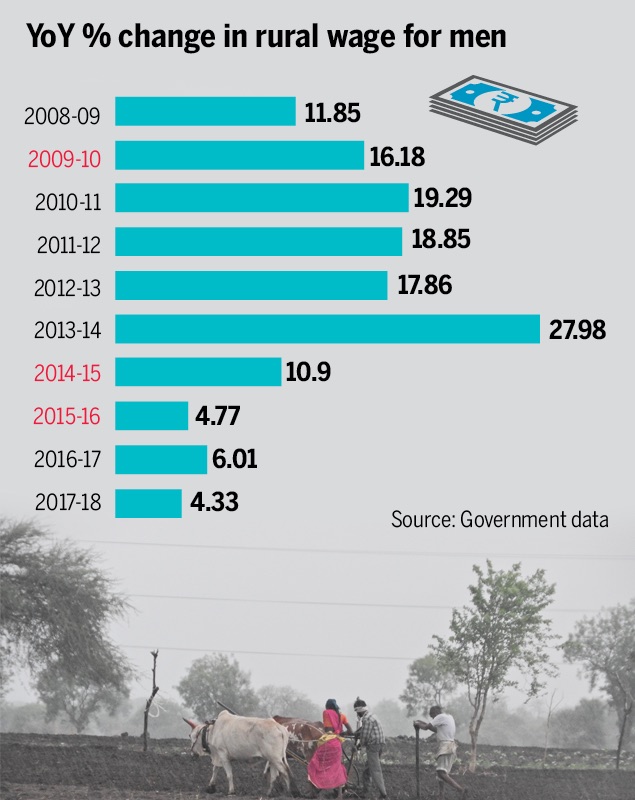

5. RURAL WAGES

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

Since food inflation and rural wages are correlated, with a fall in inflation, rural wage growth too has slowed down.

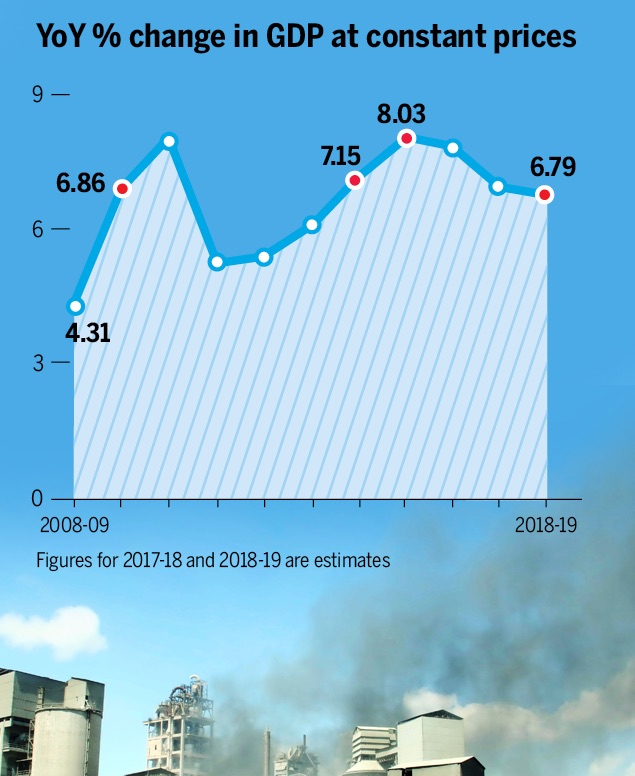

6. GDP

From: April 6, 2019: The Times of India

Largely due to the shrinking share (about 17-18%) of agriculture in India's GDP, the monsoon's direct impact on the GDP has weakened over the years.

Monsoon and agriculture

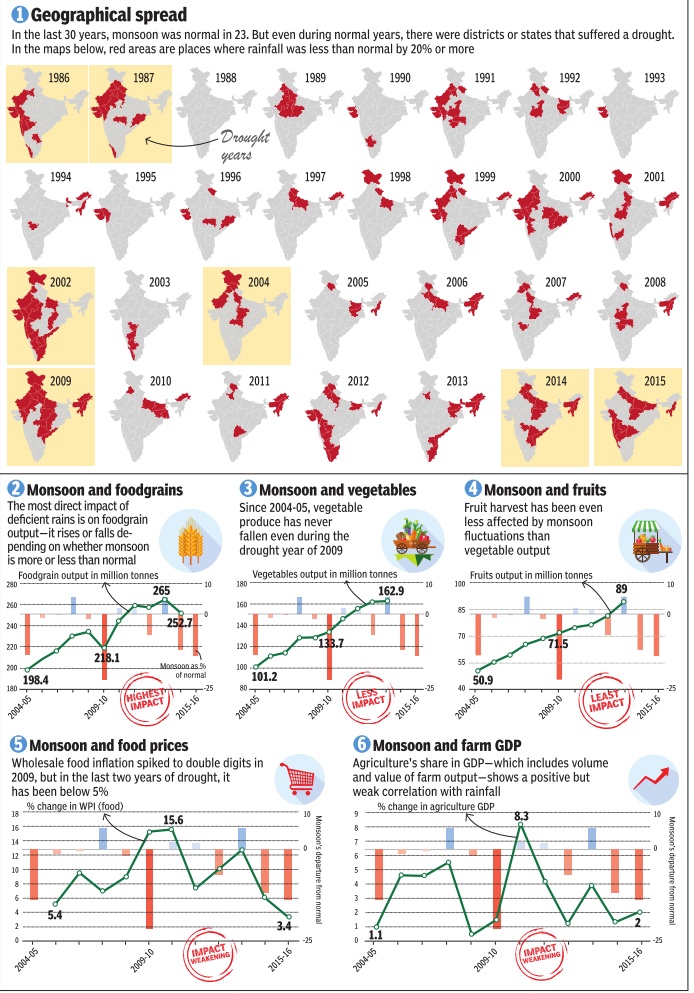

1986-2015

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India, April 18, 2016

See graphic, ' Monsoons in India: Geographical spread, monsoon and foodgrains, monsoon and vegetables, monsoon and fruits, monsoon and food prices and monsoon and farm GDP: 1986-2015'

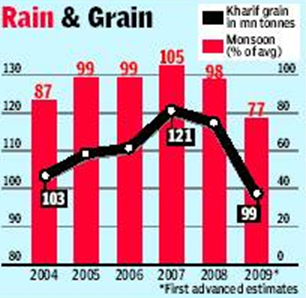

2004-09

See graphic, ' Rain and grain: 2004-09 '

2006-16

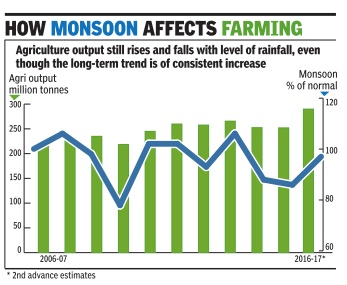

See the graphic 'How monsoon affects farming, 2006-16'

Monsoon break

Definition

A monsoon break — a period when rain activity comes to a stop in most of central India, the region where the monsoon trough is formed — is a common occurrence during the season. “The monsoon has been active without a break since mid-June. This does not happen often and is a reason why the rains were higher than the predicted 101% of LPA for July,” said D Sivananda Pai, IMD’s lead monsoon forecaster. (By Amit Bhattacharya)

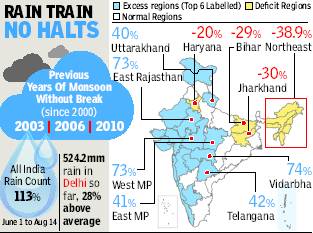

Monsoons without a break

2003-2010

Non-stop monsoon marches on

Amit Bhattacharya TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/16

One or two periods of a break in monsoon — defined as three straight days of very low rain activity across central India — are common during the rainy season. Since 2000, there have only been three years when there was no monsoon break. And all three years coincided with plentiful rains.

“Two months of monsoon activity without a break is rather rare. It’s an indication of agood monsoon,” said M Rajeevan, senior weather scientist at the earth sciences ministry.

At least four factors have worked in favour of the monsoon in 2013. The first good sign was an absence of El Nino — an anomalous rise in ocean surface temperatures in the east Pacific that is linked to monsoon failure in India.

Currently, weak La Nina conditions exist in the Pacific, which is the opposite of El Nino and is known to help the monsoon here.

“Then, typhoons breaking out over the south Pacific this season have also helped because these have generally moved in a direction that reinforces the Indian monsoon. This is consistent with the weak La Nina conditions,” said Rajeevan.

More importantly, what has helped sustain the rains — and distribute it more or less evenly across the region — has been a series of low pressure formations over the Bay of Bengal that have travelled westwards at regular intervals.

“There have been an unusually high number of low pressure systems, along with cyclonic circulation over land. These have nurtured the monsoon this year, especially in the interior regions of south and central India,” said Pai.

Lastly, Pai said a strong Arabian Sea branch of the monsoon first helped accelerate the rain coverage over the country, and also brought good rains over the west coast.

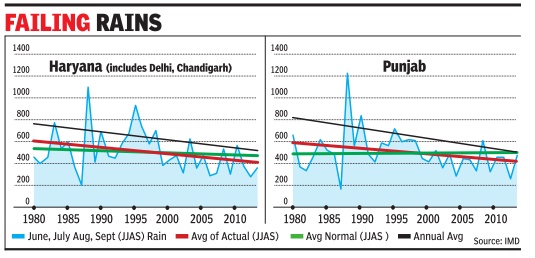

Monsoons in Punjab, Haryana

1980- 2010

See graphic, ' Monsoons in Punjab, Haryana: 1980- 2010 '

1999-2014

See graphic, ' Monsoons in Punjab, Haryana: 1999-2014 '

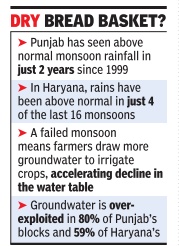

16-year trend of poor monsoon in Punjab, Haryana

Amit Bhattacharya New Delhi The Times of India Sep 22 2014

India's bread basket states of Punjab and Haryana received just around half the normal rainfall this monsoon season. But more worryingly , this year's rain deficit is not an isolated event. The two key agricultural states have been getting below par rainfall for the past 16 years.

Met department figures reveal Punjab has seen above normal monsoon rainfall in just two years since 1999. The last time that happened was seven monsoons ago, in 2008.The stats are similar for Haryana, where rains have been above normal in just four of the last 16 monsoons.

Experts are divided over why rains have been consistently failing in the region but the trend has dire implications for agriculture, which relies heavily on groundwater. The two states are among the most exploited regions in the world for groundwater.

Deficient rains add another dimension to the crisis.Groundwater mainly de pends on rainfall for recharge. So, less rain means less groundwater availability .A failed monsoon also means farmers draw more ground water to irrigate their crops, particularly paddy , accelerating the fall of the water table.

At TOI's request, Prof Krishna AchutaRao from IIT Delhi's Centre for Atmospheric Sciences plotted the annual and seasonal rainfall in the two states since 1980.The rain stats were obtained from the India Meteorological Department. A linear graph reveals a disturbing trend of decreasing rains in the bread basket of India. It shows average annual rainfall in Punjab falling during this period from just over 800mm in 1980 to less than 600mm in 2014 — a drop of roughly 200mm. Haryana’s annual average shows a similar drop, from around 780mm in 1980 to less than 580mm at present.

For monsoon season rainfall, Punjab has seen a drop of nearly 120mm, from an average of around 600mm in 1980 to roughly 480mm this year.

In Haryana, it’s down from more than 600mm to around 470mm during the same 35year period.

“The long term decrease in rainfall is apparent from the graph,” says AchutaRao, “although the rain statistics for the 1980s show very high variation.” But what’s not so apparent is the cause of the decline.

D Sivananda Pai, head of long range forecasting at IMD Pune, believes the drop is part of natural variability which will get reversed in time.

“Indian monsoon is passing through a low rainfall epoch since the 1990s. The drop in rainfall in this region could be part of that phenom enon,“ says Pai.

The story may not be that straightforward, says AchutaRao, who is coordinating multi-agency research into the Indian monsoon.

Monsoon/ water cycle

Let’s respect the water cycle

Amit Bhattacharya | TNN 2010

Think of water and chances are you wouldn’t picture a farmer digging a tubewell. Most urban Indians can’t think beyond their own water woes — dry taps; waking up at odd hours to tank up for the day. Yet, 80% of all the water India uses goes into agriculture. But even so, 60% of our farmlands remain dependent on the rains. Just as water evaporates, it seems, so do the resources that go into water management in the countryside.

The scale of this ‘evaporation’ is so massive it is surprising the issue hasn’t generated more public debate. Nothing illustrates this better than the money spent on canals. In the 15 year-period from 1991-92 to 2006-07, the government spent Rs 1.3 lakh crore on major and medium irrigation projects without achieving any net increase in the irrigated area!

If anything, India’s total canalirrigated area has decreased from 17,791,000 hectares in 1991-91, to 16,531,000 hectares in 2007-08, according to provisional figures released by the agriculture ministry. The story behind this dubious feat encapsulates almost everything that’s wrong with water planning and use in agriculture.

Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator for South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, should know. Last year, he co-authored a paper that contained exactly those startling statistics. He says it’s not about too few new canals but about “many old ones have stopped functioning, at least partially, due to siltation, lack of maintenance and faulty assumptions of water use. Then there are water management and sharing issues. Often there’s intensive water use in upstream areas which leaves no water at the tail-ends.”

Thakkar says it boils down to bad investment decisions. “The government keeps pushing for big irrigation projects without taking care of the existing ones, which in itself is a huge task. According to a 2005 World Bank report, the annual maintenance bill for India’s canal network comes to around Rs 17,000 crore. Less than 10% of that money is available,” he says.

Experts lament that new irrigation projects often fail to take into account the larger hydrological processes they would affect. They also pay little attention to water-use patterns. This has led to river basins such as the Krishna becoming over-irrigated.

Planning Commission member Mihir Shah calls such policy practices “hydroschizophrenia (or) a schizophrenic view of an indivisible resource like water, failing to recognize the unity and integrity of the hydrologic cycle.”

Shah elaborates: “It’s a strange situation. Water management in villages comes under two ministries — rural development ministry and ministry of water resources. Often the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing.”

Both Shah and Thakkar say the first step in dealing with the crisis is accepting ground realities. “While huge amounts are spent on canal systems, groundwater has emerged as the dominant method of irrigation,” says Thakkar. The latest official figures show that more than 60% of India’s 62 million irrigated hectares is fed by groundwater.

With no regulation, this has obvious perils. In August, two independent studies used satellite data from GRACE or the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment to show that northern India was losing more groundwater than anywhere else in the world except for the Arctic ice sheets. One of the studies put the annual net groundwater loss in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan at 109 cubic km, which is roughly equivalent to 109 billion tonnes. The water table has dropped dramatically in many areas and this is one of main problems Indian agriculture faces today.

Thakkar identifies four urgent policy measures: “Ensure that our old water recharge systems are sustained and enhanced, develop new recharge systems and harvest water where it falls, regulate groundwater use and, lastly, massively promote conservation methods like drip irrigation and rice intensification.”

Shah, who has been asked by the Prime Minister to write a paper for the National Development Council on a holistic water policy, says it's possible for agriculture to grow even as water use falls. “In Australia, water consumption in agriculture has reduced by 30% in the past 20 years. If they can do it, so can we,” he says.

But for that to happen, water policy has to become participatory. “The irrigation department, which is managed by civil engineers, needs to recruit people managers who understand local needs and sentiments,” concludes Shah.

It will make all the difference to a thirsty nation and parched fields.

TOTAL AREA IRRIGATED BY CANALS 1991-92: 17.8 mn hectares 2006-07: 16.8 mn hectares Amount spent on irrigation projects from 1991-92 to 2006-07: Rs 1.3 lakh crore

INFLATION IN IRRIGATION Nagarjunasagar project (AP) Original cost (pre-fifth Plan):

Rs 91.12cr Latest estimates*: Rs 1,184cr Increase: 1299%

Western Kosi canal (Bihar) Original cost: Rs 13.49cr Latest estimates: Rs 904cr Increase: 6701%

Barnar (Bihar) Original cost (in seventh Plan): Rs 8.03cr Latest estimates*: Rs 216.23cr Increase: 2689%

- All ‘latest estimates’ as on 2003, according to Planning Commission document

Monsoon: floods

Every monsoon means flood of bad news

Shobhan Saxena | TNN 2010

In the great plains of India, there is nothing romantic about the monsoon. People’s fate depends on the monsoon’s mood swings. If it fails to keep its date with the country, there is drought. If it’s over generous, the floods cause death and destruction. Even when it’s “normal”, some river somewhere exceeds the danger mark and kills a few hundred people. After the skies clear and the water recedes, armies of mosquitoes and bugs launch attacks. Millions fall prey with chills, cramps, fever. In this part of the world, drought, deluge and death are as much an annual phenomenon as the monsoon.

Bangladesh may be famous for its notorious floods, but India is not far behind. Every year, the monsoon floods leave a trail of destruction in India. Roughly 20% of deaths caused by flooding worldwide occur here; some 30 million people are evacuated every year. Every year witnesses an “unprecedented flood”. Every other year the “worst flood in living memory” leaves scores dead. Is India becoming ever more vulnerable to monsoon fury?

No, say Vinod K Sharma and A D Kaushik of the National Centre for Disaster Management in a recent paper on floods in India. They argue that states did not appear quite as vulnerable as before because there was less developmental activity and population pressure. “However, in the present time, unabated population and high rate of developmental activities forced on the occupation of flood plains has made the society highly vulnerable to flood losses,” they wrote.

In 2009, the monsoon was weak and deficient but it caused floods, deaths and displacement in Orissa, Kerala, Karnataka, Gujarat and the north-eastern states. In 2008, the monsoon was normal, but Bihar faced the worst flood crisis ever as the Kosi breached its embankment, changed course and deluged several districts, leaving hundreds dead and three million homeless.

‘Normal’ monsoons

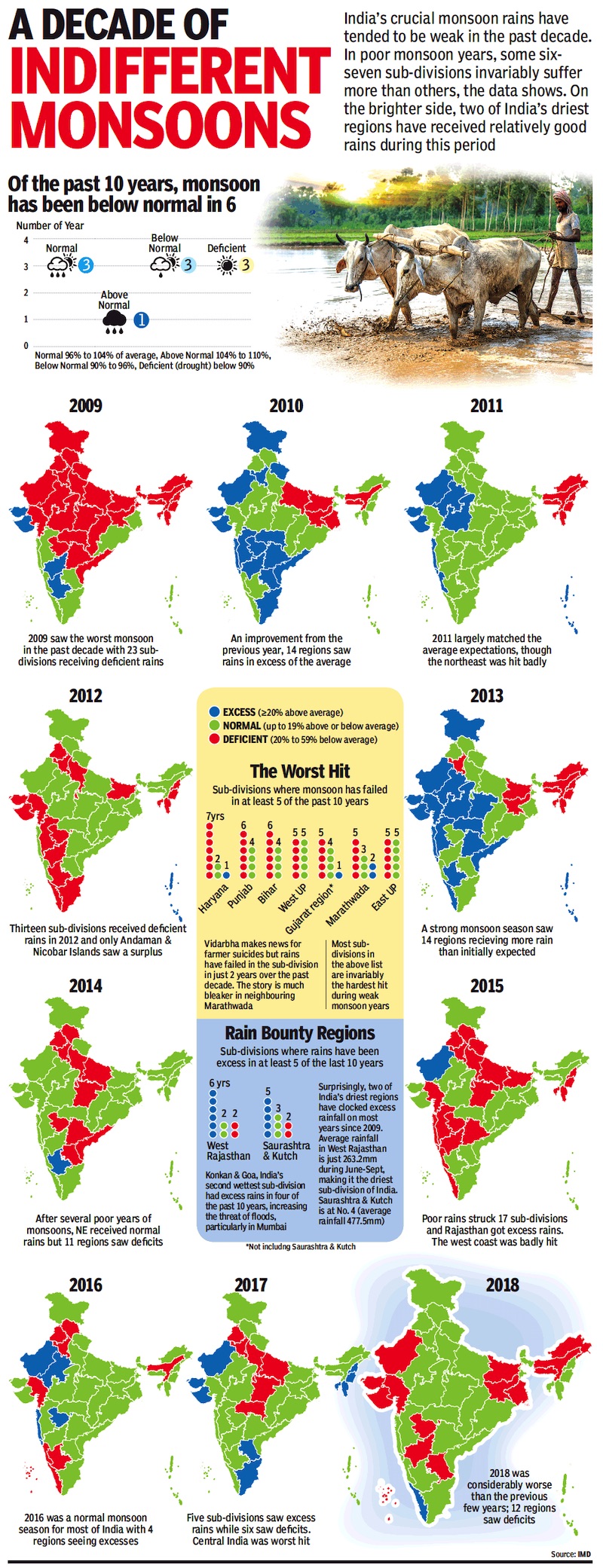

2009-18: normalcy is a myth

February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) said the country is likely to have a ‘near normal’ monsoon this year at 96% of the Long Period Average (LPA) -- an encouraging signal for farmers and the overall economy.

A normal monsoon is considered to be 96-104% of the LPA of 89 cm for the entire four-month season beginning June to September. Above-normal is 104-110%, below-normal is 90-96% and deficient (drought) is below 90%. LPA is defined as the average annual rainfall over a 50-year period between 1951 and 2000.

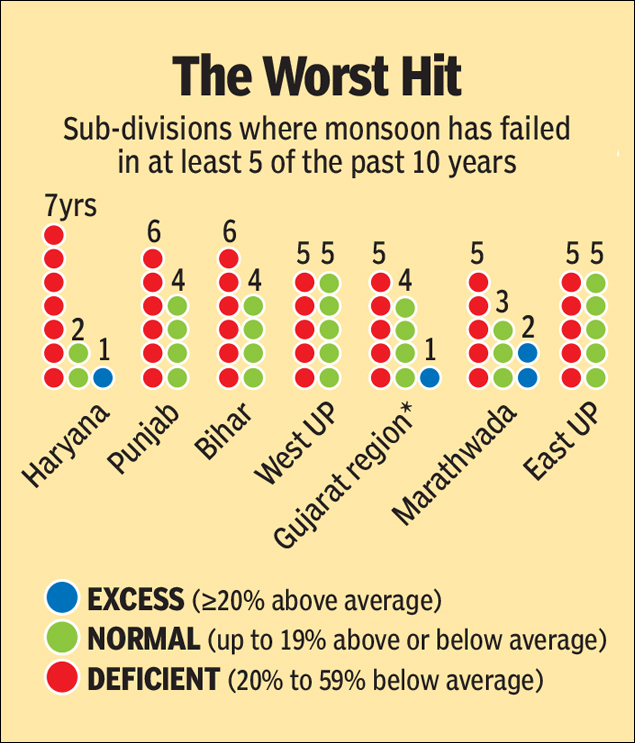

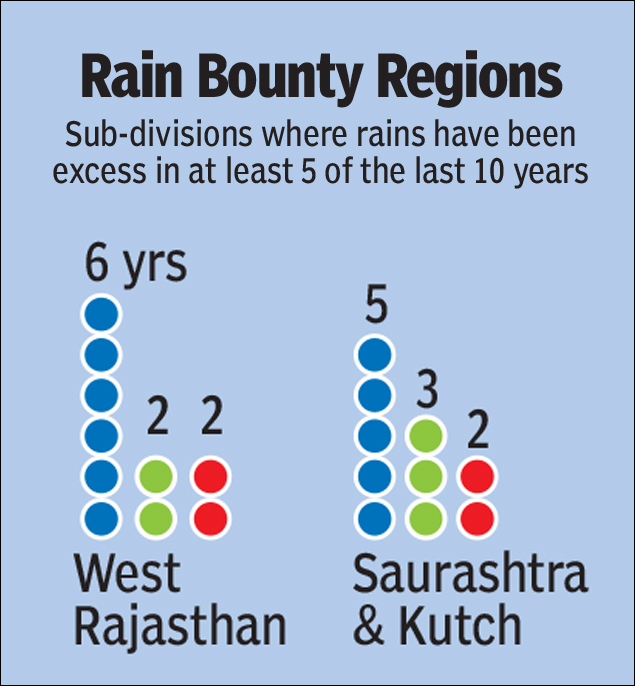

Of the past 10 years, India's crucial monsoon rain has been below normal in six years. IMD divides the country into 36 meteorological sub-divisions, mostly corresponding with state boundaries, with bigger states being divided into 2 or 3 sub-divisions, based on climatological uniformity. In poor monsoon years, some 6-7 sub-divisions suffer more than others, the data shows. On the brighter side, two of India’s driest regions have received relatively good rains during this period.

A look at the monsoon pattern from 2009-2018:

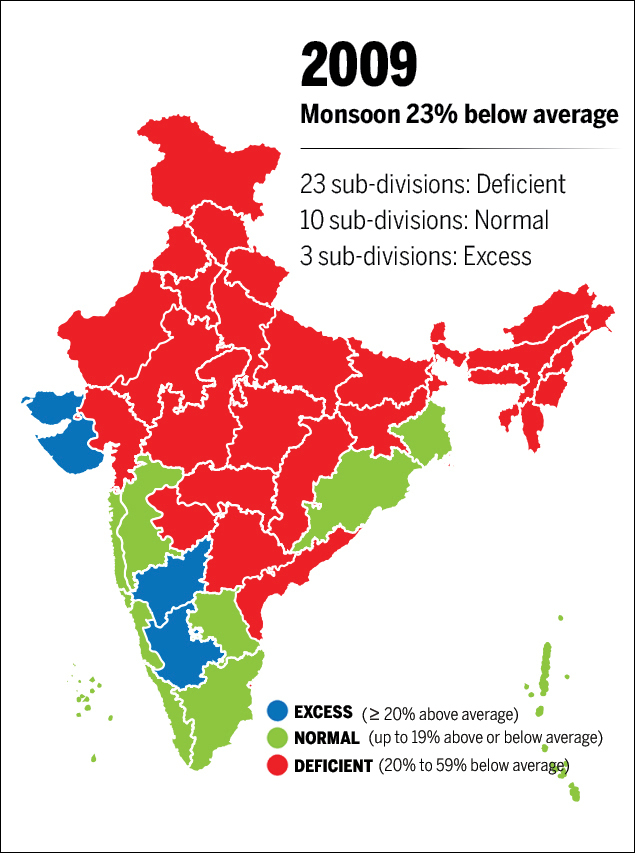

2009

An El Nino year that saw the weakest monsoon and the worst drought in 37 years, in which 23 sub-divisions received deficient rains.

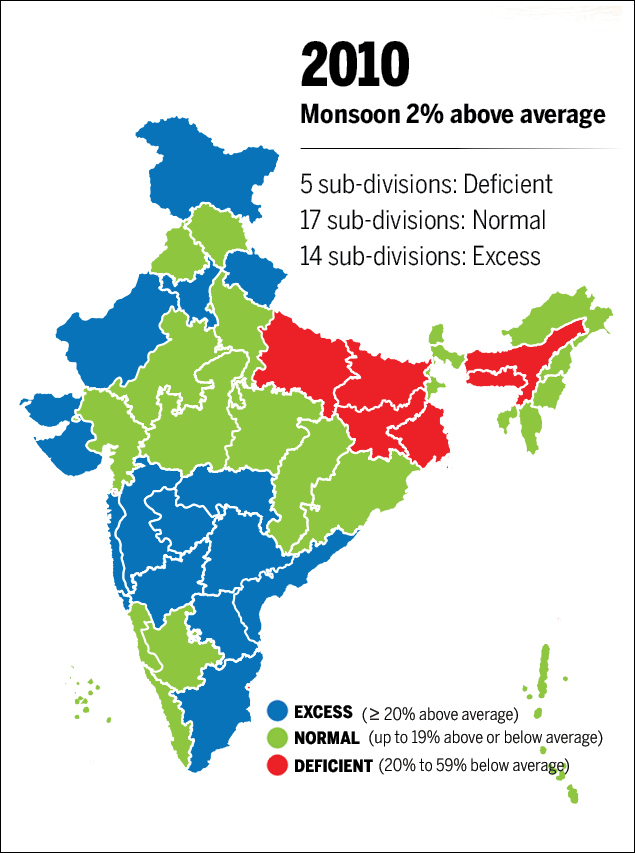

2010

2010 was a vast improvement from the previous year; 14 subdivisions (in blue) had excess rainfall.

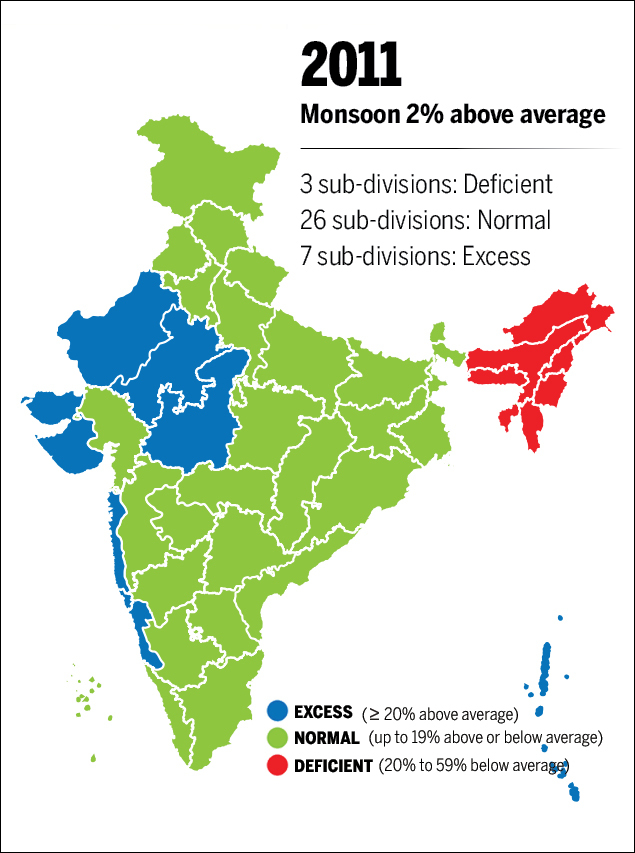

2011

Probably the best monsoon year of this period with the most well-distributed rainfall. No subdivision apart from the northeast (in red) had deficient rains.

2012

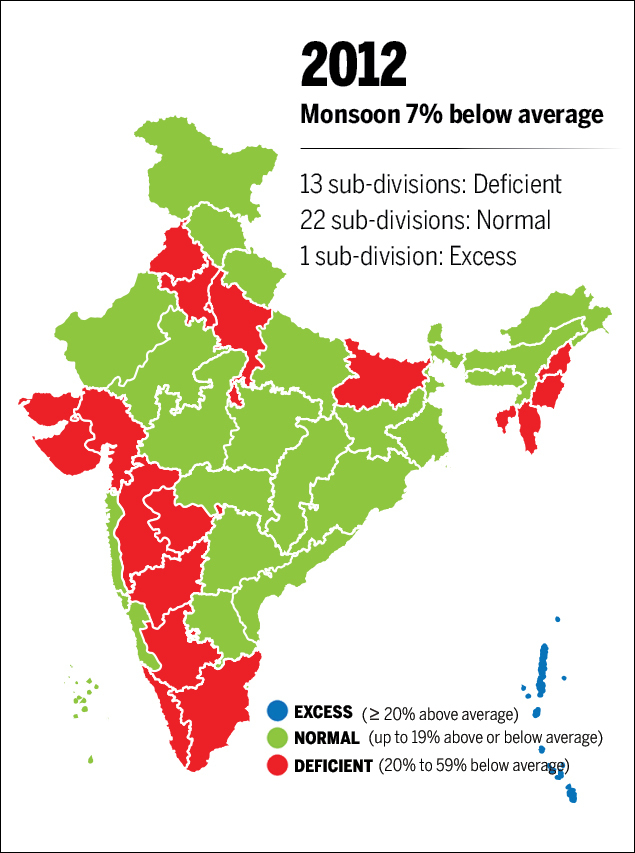

Monsoon came under the shadow of a warming Pacific although El Nino did not develop. Thirteen sub-divisions received deficient rains in 2012 and only Andaman & Nicobar Islands saw a surplus. 2013

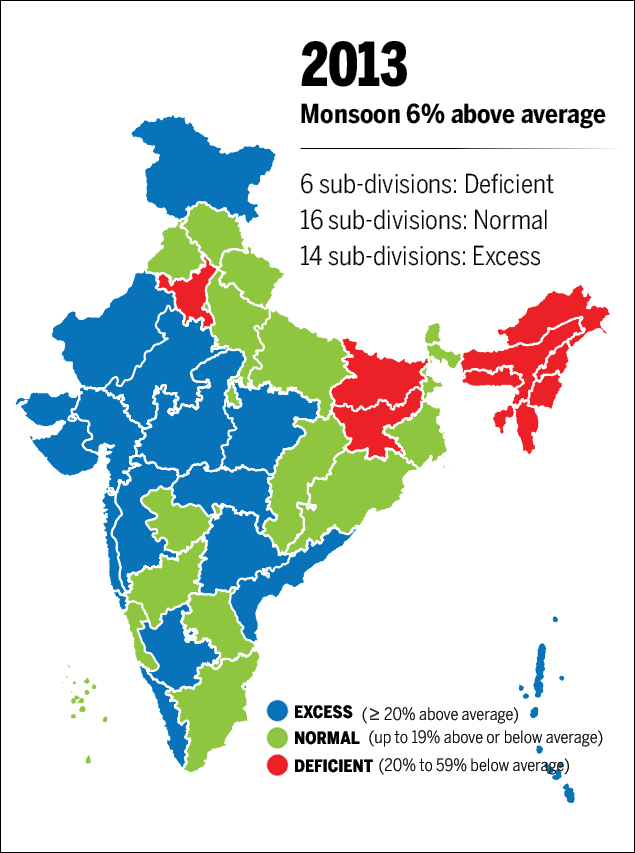

The strongest monsoon of the period, with the earliest onset in decades over north India. Cloudbursts caused the deluge in Kedarnath, Uttarakhand. Swathes of blue across the country meant 14 regions received more rain than initially expected.

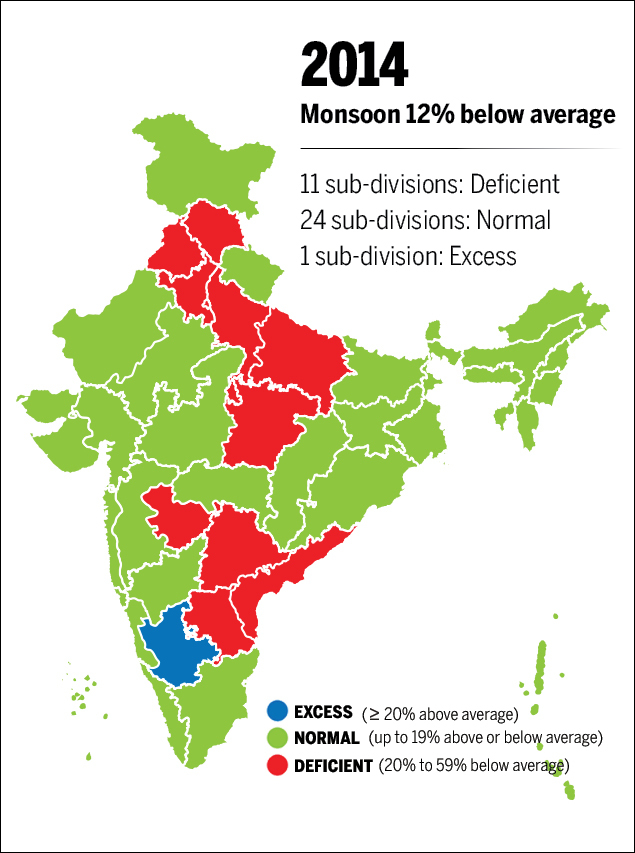

2014

A drought year with monsoon hit by evolving El Nino conditions that didn't eventually form. After several years of poor monsoon, the northeast received normal rains, but 11 regions saw a deficit.

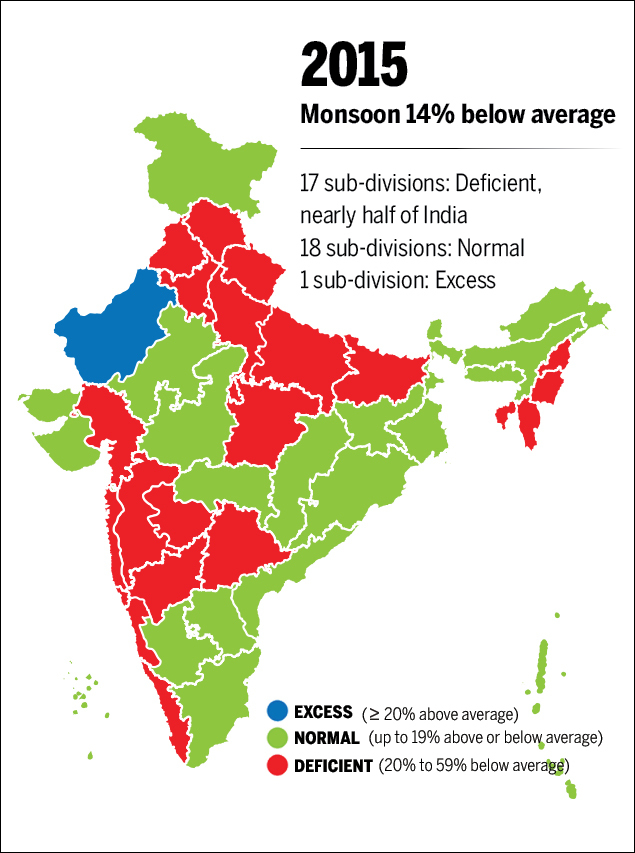

2015

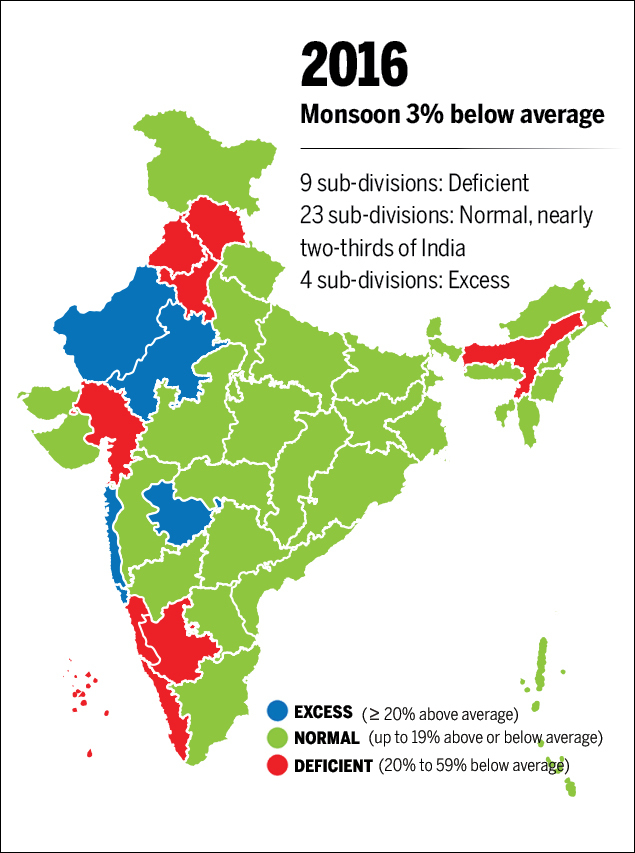

An El Nino year that lead to the second straight drought year. Agriculture output dipped and water shortages abounded. Poor rains struck 17 sub-divisions, this included the west coast. Rajasthan, in blue, was the only area that got excess rains. 2016 First normal monsoon in three years saw good rains in central India. Agriculture output grew after a two-year lows . Four regions saw excess rainfall. 2017

It was a below-normal monsoon year with most of the north and parts of central India in rain shadow. Five sub-divisions saw excess rains, while more than two-thirds of India, or 25 sub-divisions, had normal rains.

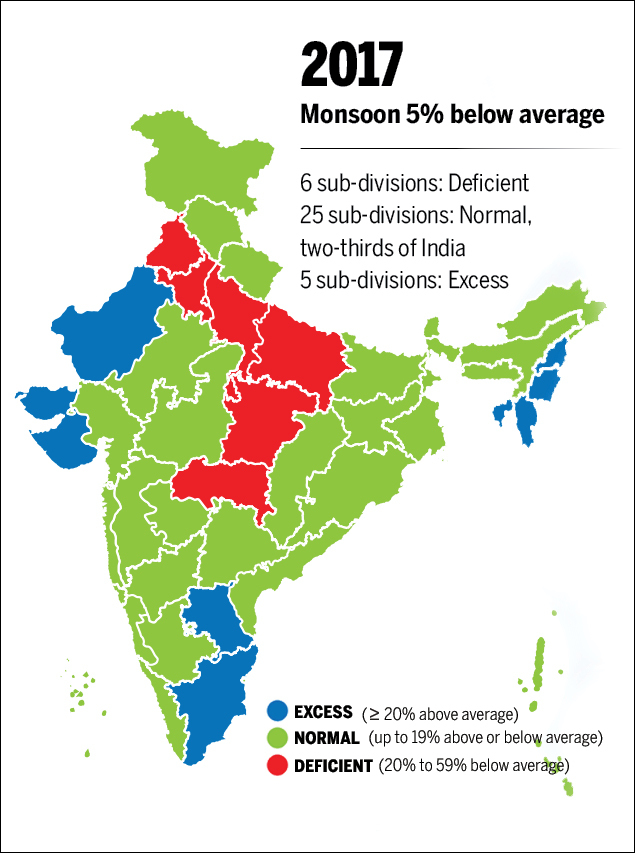

2018

2018 was the second below-normal monsoon year in a row. However, rains were better distributed than in 2017, with north India, for once, getting satisfactory rainfall. Twelve regions saw deficits. Kerala, however, saw excess rainfall which led to devastating floods.

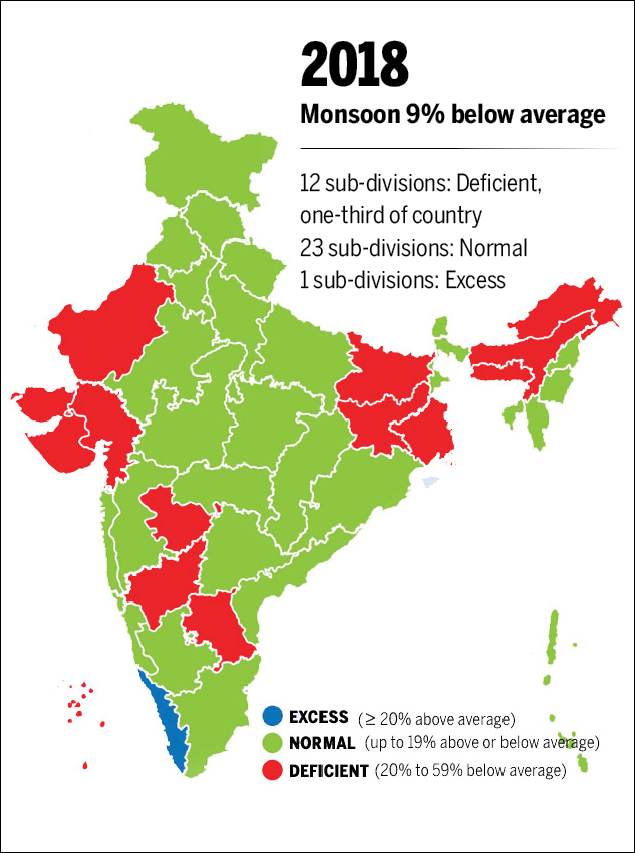

Haryana, Punjab among worst-hit regions

Vidarbha makes news for farmer suicides but rains have failed in the sub-division in just 2 years over the past decade. The story is much bleaker in neighbouring Marathwada.

Most subdivisions in the above list are invariably the hardest hit during weak monsoon years.

Regions that received excess rains

Konkan and Goa, India’s second wettest sub-division had excess rains in four of the past 10 years, increasing the threat of floods, particularly in Mumbai.

Surprisingly, two of India’s driest regions have clocked excess rainfall on most years since 2009. Average rainfall in West Rajasthan is just 263.2mm during June-Sept, making it the driest sub-division of India. Saurashtra and Kutch is at No. 4 (average rainfall 477.5mm).

How accurate are weather forecasters?

IMD's forecast for 2019 directly challenges the prediction of India's only private sector weather forecaster, Skymet, which is slightly more pessimistic with a forecast of 93%. Both the IMD and Skymet have hit the bull's eye an equal number of times in the last six years. IMD was off the mark in 2014, 2015 (which turned out to be drought years) and 2018, which narrowly escaped a drought.

Number of rainy days…

…in a typical June, July or August

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic, ' Average monsoon rainfall and number of rainy days in major Indian cities, and towns with the highest rainfall in India, in June, July, August '

…in June, July and August, 2015

The Times of India, May 30 2015

India receives most of the rainfall in four monsoonal months-June, July, August and September. The Met department defines normal monsoon to be 96 to 104% of the long period average, usually the average monsoon over 30 years. If the rainfall deficiency is more than 10%, it would typically be called a drought year. Last year's monsoon was deficient by 12%. This year's monsoon rainfall is predicted to be 93% of the average. If this year's monsoon deficiency crosses 10%, it will be one more year of drought, making it two successive years of drought, an event that has happened only three times in the past 113 years (1904-05, 1965-66 and 1986-87). In 1917, monsoon exceeded normal by the highest percentage (22.9) in 113 years. In 1918, monsoon was deficient by 24.9%, the highest deficiency for this period

‘Neutral’ years

1997-2017: vis-à-vis El Nino, La Nina years

From: Amit Bhattacharya, In ‘neutral’ years, monsoon isn’t always normal, April 17, 2018: The Times of India

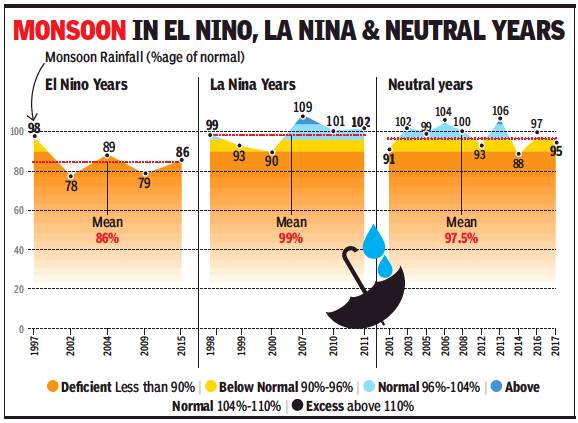

Neither El Nino nor La Nina is expected to impact the monsoon this year, the met department said on Monday. While such ‘neutral’ years are generally associated with normal rainfall, a look at the past 21-year record shows a wide variation in monsoon’s performance.

From 1997 to 2017, there were 10 neutral years during which the monsoon varied between 88% of average (drought) to 106% (above normal). On the whole, the mean monsoon performance during these neutral years was 97.5% of the long period average (LPA), which is in the lower end of the normal range (96%- 104%) — indicating that monsoons have been generally depressed in the current era.

The mean monsoon output in the neutral years, however, is way above that of El Nino years (86%) and below the mean for La Nina years (99%). These differences highlight the strong connection of the Indian monsoon with El Nino and La Nina, which are opposite conditions in the Pacific Ocean.

El Nino is an abnormal warming of surface waters in the east and central equatorial Pacific which negatively impacts the monsoon. La Nina is the opposite — an abnormal cooling of waters that aids the monsoon. As the 21-year data shows, there are years when this relationship doesn’t hold.

However, the monsoon’s performance varies significantly during the neutral years as well. These variations are a result of many other local and large-scale factors. Among the large scale factors is the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), which is expected to be weakly negative during the second half of this year’s monsoon. A positive Indian Ocean Dipole phase is seen to generally aid the monsoon while a negative phase could depress rains.

Another highly unpredictable condition with sharp, although short, impacts on rainfall is the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), a periodic eastward moving weather disturbance close to the equator. MJOs can depress or enhance rainfall for a week or two, depending on their position and strength. Slow-moving or stationary MJOs can have longer impacts. A well-positioned MJO can invigorate the monsoon while its absence tends to prolong breaks in monsoon rains. MJOs, however, are very hard to predict.

Finally, the distribution and intensity of monsoon rains comes down to the number of low-pressure systems and depressions coming inland from the Bay of Bengal. During active monsoon periods, the frequency of these systems are usually high. On some occasions, even winds from the northwest (western disturbances) affect rainfall.

The interplay of all these factors make monsoon forecasting a highly hazardous profession.

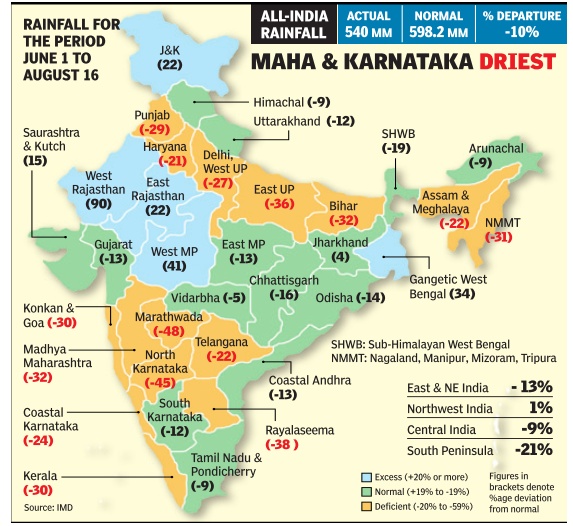

In 2015

See graphic:

Rainfall, June 1-August 16, 2015

Withdrawl of monsoons

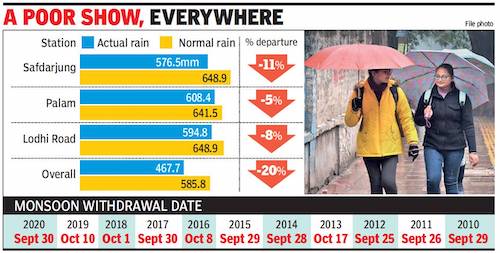

Delhi

2010- 2020

From: Priyangi Agarwal, October 1, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic:

The withdrawal date of Monsoons in India, 2010- 2020

2020: 13 days late

October 28, 2020: The Times of India

Southwest monsoon withdraws, 13 days after normal schedule

NEW DELHI: The southwest monsoon finally withdrew from the entire country on Wednesday, 13 days after its normal date of final withdrawal. With the final withdrawal, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) said the northeast monsoon, a phenomenon that brings rainfall in extreme south peninsular India, has commenced. Analysis of withdrawal dates of southwest monsoon from the entire country during 1975-2020 period shows that the 2010 had seen the most delayed withdrawal on October 29.

Like this year, the withdrawal date in 2016 was also October 28 while 2000 and 2017 had seen it on October 25. Predicting weather conditions during next few days, the IMD said, “Scattered rainfall with moderate thunderstorm and lightning is very likely over Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry during next five days with isolated heavy falls over south Tamil Nadu on October 29.”

YEAR-WISE DATA

1901-2013

1901-2013: There are two detailed, year-wise graphics elsewhere on this page.

Years of excessive rain and most deficient rain in monsoon season, 1901-1945

and

Years of excessive rain and most deficient rain in monsoon season, 1946-2013

2009-18

From: April 16, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Years of excessive rain and deficient rain during the monsoon season, 2009-18

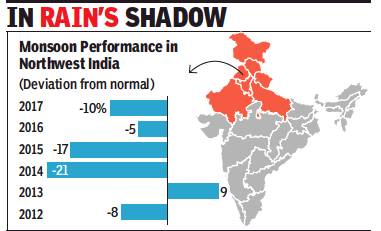

2012, 2014-17: deficit monsoons

From: Amit Bhattacharya, After 4 bad years, IMD says north India to get good rains, June 1, 2018: The Times of India

The India Meteorological Department’s forecast of a normal monsoon in northwest India will bring cheer to the crucial agricultural region, where rainfall has been below-par for four years in a row. If the forecast holds, northwest India is in for its first no-deficit monsoon since 2013.

In its region-wise monsoon forecast released on Wednesday, IMD predicted 100% seasonal rainfall in northwest India, a region comprising J&K, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. In meteorological terms, 100% corresponds to rains that are exactly normal.

Being farthest from the seas, northwest India is at the tail end of the monsoon system, which arrives here after traversing the rest of the sub-continent. That’s why the normal monsoon season rainfall here is 615mm, way lower than the country’s normal of 887mm for the June-September period.

In recent years, however, monsoon in the northwest has been mostly below normal. Since 2012, the region received an above-normal monsoon only in 2013, a year that brought disasters of a different kind — cloudbursts and flash-floods in parts of Uttarakhand.

It is said, when monsoon fails in India, it fails spectacularly in the northwest. The drought years of 2014 and 2015 saw gaping monsoon deficits of 21% and 17%, respectively, in the region. Even last year, when the country had a near-normal monsoon, northwest India ended up with a rain shortfall of 10%.

The failing rainfall in recent years has not seriously impacted agricultural output in the region. That’s because farmers still have access to water due to perennial rivers, a good irrigation network and groundwater. However, deficient rainfall takes a big toll on the region’s scarce groundwater resources, which have anyway been depleting at an alarming rate.

Large parts of northwest India fall in the zone that has among the highest rates of groundwater extraction in the world. A bad monsoon puts further stress on this resource while adding to the inputs costs of farmers.

Further, poor winter rainfall in the region this year, particularly in the western Himalayas, has led to reduced levels in north India’s perennial rivers and other water sources. Timely arrival of monsoon and good rains will thereafter will go a long way in alleviating water stress on all fronts.

2013

Monsoon going strong, hopes soar

Rains Set To Cross 100% Of Long-Period Average, Record Rice Output Likely

Neha Lalchandani TNN

The Times of India 2013/08/02

A bountiful monsoon normally benefit the kharif crop and augurs good rice production with the area under sowing touching 196 lakh hectares in 2013, a 16 lakh hectare increase over 2012.

2015

17% rain deficit in July 2015

The Times of India, Aug 02 2015

Amit Bhattacharya, Vishwa Mohan & Neha Madaan

Dry days: 17% rain deficit in July

After a wet June, when other systems had countered the adverse effects of El Nino, monsoon took a drier turn in July and the month ended with a countrywide rain deficit of 17%. However, kharif sowing remained robust, boost ed by good rain spells in sev eral parts of the country . With the dip in rains monsoon's performance in the first half of the season -June 1 to July 31 -was 5% below the long term average June had a monsoon surplus of 16%.

Heavy rains in Gujarat Rajasthan, West Bengal Jharkhand and parts of cen tral India masked the fact that July this year was the driest since 2002 in terms of average rainfall across the country . The month started on a weak note and rains re mained below par till July 19, except for a brief four day period from the 9th.

But there were several redeeming features. “The rainfall, although weak, has been fairly well distributed across most parts of the country ,“ said D Sivananda Pai, head of India Meteoro logical Department's long range forecasting section.

However, some distress zones of low rainfall have started emerging. Rains were consistently weak through July in south India as well as subdivisions such as Marath wada and Madhya Maharash tra. From July 1 till 29, the southern peninsula recorded the highest rainfall deficien cy in the country , at 46%.

“We had forecast an 8% rainfall deficit for July , but it has turned out to be more. A typical feature this year has been that most rain-causing disturbances have been com ing from the east. Indian Ocean's monsoon circulation has been weak, which means that the monsoon pulses are not progressing from the south, which has caused a significant rainfall deficiency in the southern parts,“ a Met department official said.

However, rains in the north, most parts of central India and many regions of the east were close to normal.This is reflected in the kharif crop sowing figures. The overall sown area has, so far, been far ahead of the corresponding figures last year, which was a bad monsoon year.

The area under kharif as on Friday (July 31) was still less than what was reported at this time in 2013, when rains were plentiful in the monsoon months. As compared to 819.99 lakh hectares as on August 2, 2013, the kharif sown area this year was 764.28 lakh hectares as on July 31.

The monsoon is predicted to be active through the first week of August, raising hopes that the net sown area would grow in the coming days.

Several agencies, howev er, have predicted a relatively dry period in the country after the first week of August when the monsoon could go into a break, increasing the overall rain deficit.

In its monsoon update in June, IMD had forecast a 10% rain deficit in August. The department will issue another update for the second half of the season in a day or two. It had in June predicted a drought year, with overall seasonal rains at 12% below normal. Meanwhile, private forecaster Skymet downgraded its prediction for the season from 102% to 98%, still staying within the normal range.

PM explores ways on sugar exports

M Modi called for renewed P efforts to raise ethanol blending of fuel and exploring all possibilities for sugar exports as he brainstormed with key ministers and officials to resolve the problems faced by the sector.He reviewed the progress with regard to the Rs 6000 crore incentive package approved by the Centre in June and emphasized that the farmers' interest be kept foremost at all times.

2016

June 2016: 11% Monsoon deficit

The Times of India, July 01, 2016 Amit Bhattacharya

11% monsoon deficit in June

Monsoon remained slightly below expectations in the first month of the rainy season as June ended with a countrywide deficit of 11%, mainly on account of a delayed onset. Despite the deficit, however, rains have been in the normal to excess range in around two-thirds of India's 36 meteorological subdivisions. “The deficit in June was mainly due to the eight-day delay in monsoon's onset. It progressed well after that but did not perform as expected in central India.But the shortfall should be made up in July ,“ said D Sivananda Pai, lead monsoon forecaster at the India Meteorological Department.

The Met department expects rains to pick up in July , the most crucial month of the season for kharif sowing.Monsoon's performance in July is also important for water recharge as it accounts for almost a third of the total seasonal rainfall. By contrast, June normally gets only around 18% of the total monsoon rains.

“The monsoon hit the country only on June 8. So, we have got just about three weeks of monsoon rains so far. By that measure, an 11% shortfall is well within range,“ said B P Yadav, director, IMD. Among the meteorological regions of the country , south India received the best rain bounty , with 22% excess rains in June.Although the monsoon is yet to arrive in many parts of northwest India, the region had just a2.4% rain shortfall because of fairly good pre-monsoon showers in states such as Punjab.

The highest shortfall was in east and northeast India, where June ended with a 27.3% deficit. The performance wasn't totally unexpected because the region is predicted to receive less rains this year.

The region where monsoon has been more or less disappointing is central India, which had an 18.2% deficit in June. Except for Konkan and Goa, Marathwada and west Madhya Pradesh, rainfall has been less than average in all subdivisions of the region.

While Odisha and east MP are expected to get rains in the next days, other subdivisions in the region where the deficit is high -Gujarat and Madhya Maharashtra -may have to wait a few more days for good rainfall, Met officials said.These areas too would get good monsoon showers in July , they added. “In the next few days, monsoon activity is likely to be concentrated in northwest India and adjoining parts of central India. We expect monsoon to hit Delhi, Haryana, Punjab and more parts of UP and Rajasthan in the next two-three days,“ said Yadav.

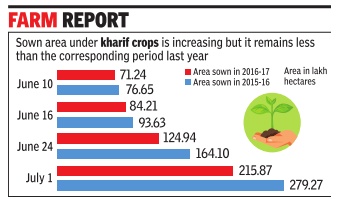

Deficit hampers kharif sowing

The Times of India, Jul 02 2016

Vishwa Mohan

Deficit rainfall hampers kharif sowing in June 2016

Deficit monsoon rains in June has affected the overall kharif sowing operation in the month, keeping the sown area low as compared to the corresponding period last year but the area under paddy has shown improvement for the first time this season as compared to 2015-16.

Kharif sown area data, released by the agriculture ministry on Friday , put the total area at 215.87 lakh hectare as on July 1 as compared to 279.27 lakh hectare at this time last year. However, the paddy recorded marginal increase by covering 47.77 lakh hectare so far this year as compared to 47.62 lakh hectare in 2015-16.

Sowing operations, which remained sluggish during the first three weeks after the onset of monsoon, picked up pace in the past one week due to good rains in south India -covering over 90 lakh hectare under various crops in the past seven days.

“Though the area under kharif crops, including pulses, oilseeds and cotton, is still less than the area during the corresponding period last year due to 11% of deficit rainfall in June, the sowing operation will further pick up in July and hopefully cross the last year's sown area by the end of this month“, said an official.

Areas under pulses and oilseeds will, however, continue to be a major concern.Sown area under oilseeds stands at merely 28.71 lakh hectare as on Friday as compared to 54.24 lakh hectare at this time last year. Similarly, cotton too recorded poor sowing as its sown area stands at 30.59 lakh hectare as compared to 60.16 lakh hectare in the 2015-16.

The availability of water in the country's 91 major reservoirs has marginally increased from 23.20 billion cubic meter (BCM) on June 23 to 23.94 BCM as on June 30 despite constant withdrawal of water from them.

According to the Central Water Commission, Rajasthan, Tripura and Andhra Pradesh have better storage in 2016 than the corresponding period in 2015.

2017

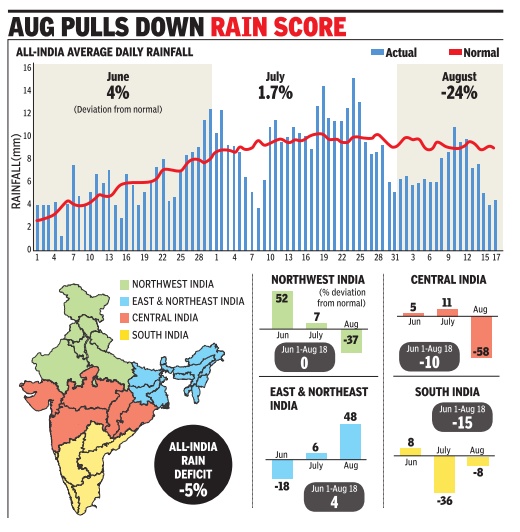

Despite floods, 5% rain deficit

Amit Bhattacharya, Despite floods, India faces 5% rain deficit, August 19, 2017: The Times of India

Large Parts Receive Poor Rain In August

The flood fury in Assam, Bihar, Bengal and Uttar Pradesh has taken attention away from poor monsoon rains in large parts of the country in August. The month has so far seen a 24% rain deficit (till August 18), with central India in particular reeling under a prolonged break in the monsoon.

The lull in rains has opened up a huge 58% shortfall in central India, and 37% in the northwest, for the month of August, pulling down monsoon's performance since June 1 to belownormal zone. The overall deficit now stands at 5% of the long period average.

However, the good news is that the monsoon is set to revive, the India Meteorological Department officials said. “By the weekend, the monsoon will become more active as a low pressure system is forming in the Bay of Bengal. We expect the situation in central India, west coast and the peninsula to improve,“ said D Sivananda Pai, head of IMD's longrange forecasting division.

The monsoon went into a break in the last week of July, when a weather disturbance, called Madden Julian Oscillation, appeared in the eastern Indian Ocean and depressed rains over the subcontinent.

“Since then, no low pressure systems formed in the Bay of Bengal. Neither did any storm system move west from the Pacific to aid the monsoon here. There were no impulses from the Indian Ocean either,“ Pai said.

“Now, there's some activity in the Indian Ocean which should progress northward towards India,“ he added.

While central and south are expected to get wet spells in the coming days, northwest India will have to wait to more conducive conditions.

“Northwest may not improve a lot unless there's an interaction of a western disturbance with the monsoon system,“ Pai said.

The three-week monsoon break has led to several meteorological subdivisions becoming rain “deficient“, showing a deficit of at least 20%. These include Haryana, west Uttar Pradesh, east and west Madhya Pradesh, Marathwada, Vidarbha, entire Karnataka and Kerala.In most other parts of India, comprising 26 of the 36 subdivision, rainfall has been normal or excess.

As is usually the case during a break in the monsoon, northeast India and the Himalayan regions continued to get rain in the first half of August, causing rivers to swell and flood the Gangetic plains. East and northeast India region has a 48% rain surplus so far in August, which IMD expects to decrease slightly in the second half. South India, which was the country's driest region in July with a 36% deficit, has had better rains in August. It still has an overall deficit of 16%.

Deficient rainfall brings down kharif sowing

Vishwa Mohan, Deficient rainfall brings down kharif sowing, August 19, 2017: The Times of India

Sending worry ing signals to the farm sector, deficient rains in central and peninsular India have taken toll on the ongoing Kharif (summer crop) sowing operation, bringing down the total acreage as on Friday, as compared to the sown area during the corresponding period last year.

Oilseeds and pulses are the worst hit. It will increase the country's import bill if sowing does not pick up in next two-three weeks. India, in any case, has to depend on imports to meet its domestic demand for these crops.

Latest crop-wise figures, released by the agriculture ministry on Friday , show that the total Kharif sown ar ea as on Friday stand at 976.34 lakh hectares as compared to 984.57 lakh hectares at this time last year -a clear indication that the current crop year (2017-18) may not be as good as 2016-17 in terms of production despite normal monsoon in many parts of the country .

Though the total sown area has dipped below last year's corresponding period level for the first time on Friday this monsoon season, sown area under oilseeds has consistently been declin ing for the past four weeks.

Similarly , pulses too has shown declining trend in past two weeks with sown area under pigeon pea (arhar), moong and soyabean declining by 18%, 6% and 9% respectively as compared to their acreage at this time last year. Sown area under oilseeds stand at 157.36 lakh hectares (LH) as compared to 175.10 LH at this time last year -the highest dip in terms of acreage so far this season.

Less rainfall means poor storage of water and lower acreage in the Kharif season and also during Rabi (winter crop) sowing operation, beginning October. Less moisture content in soil also affects Rabi crops. If low rainfall phase continues in these areas, its effect will be felt on overall production.

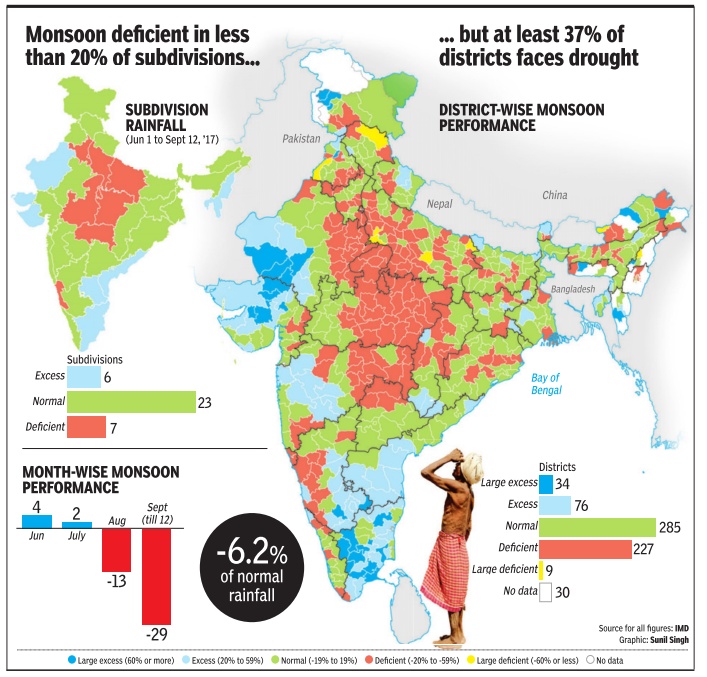

235 districts were deficit; after floods came drought

Around 235 districts across the country face the prospect of drought this year as the monsoon appears headed for a below-normal performance, with the season's deficit currently at 6.2% of normal.

These districts, accounting for 37% of the country's 630 districts for which rain data is available, have monsoon shortfall of at least 20%, with nine show acute deficits of 60% or more, data from the India Meteorological Department reveals.

A majority of the distress districts lie in the hinterland, in a swathe running through Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Vidarbha. Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and MP are the hardest hit states, showing rain deficits of 31%, 28% and 25%, respectively .

The deficits have grown gradually since the end of July, when the monsoon started failing in central and north India. The first two months of the season, June and July , ended with a countrywide rain surplus of 2.5%. Monsoon's performance since August 1 has been a dismal 17% below normal (till September 12), with good rainfall being mainly restricted to south and northeast India.

“A number of factors worked against the monsoon since July-end. There have hardly been low-pressure circulations since then and conditions in the Indian and Pacific oceans have been unfavourable,“ said D Sivananda Pai, head of IMD's long range monsoon forecasts.

IMD had forecast normal monsoon this year at 96% of long period average, which it updated to 98% in June.

Poor distribution of rainfall has added to the distress.As many as 110 districts have had excess or `large excess' (over 60% of normal) rainfall. In addition, heavy rain spells in Gujarat, Rajasthan and catchment areas in the Himalayas (particularly in Nepal) caused the worst floods in the country in 10 years.

Ironically , states such as UP have seen both flood fury as well as the prospect of drought. The monsoon deficit in west UP stands at 37%, highest for any subdivision in the country . Of the state's 72 districts, rainfall has been deficient in 48. Of these, five districts -Agra, Hamirpur, Mahamayanagar, Amethi and Kushinagar -face acute shortfall of 60% or more.

This combination of poor rains and floods is likely to hit kharif output, although data till September 8 reveals that the sowing area this year is only marginally less than last year's, with the biggest drops seen in oilseeds, pulses and jute. Several state governments have reported ly started drought exercises.

Poor rains have affected water storage levels, important for winter crops. According to the Central Water Commission data, live storage at 91 important reservoirs in the country was at 58% of capacity on September 8, lowest in five years for which data was available. It was lower than the corresponding period during drought years of 2014 (74%) and 2015 (59%), and significantly below the 10-year average of 69%.

IMD believes the second half of September could bring better rains in central India. “While the situation in northwest is not likely to change too much, there are indications that central India may get some rain in the next couple of weeks. Monsoon isn't likely to start withdrawing in the next few days,“ Pai said.

Monsoon ends 5% below normal

The southwest monsoon has begun to withdraw from the country , some two weeks later than normal.With just three days to go for the official end of India's rainy season, it is now fairly certain that this year's monsoon will end in the below-normal zone.

The India Meteorological Department announced on Wednesday that the monsoon had retreated from the western parts of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan, as well as the northwestern tip of Gujarat.

“We expect the monsoon to withdraw completely from northwest India and adjoining parts of central India in the next two-three days. Dry weather is forecast in the region and there's a substantial drop in moisture levels, making conditions favourable for the retreat,“ said M Mohapatra, head of services at IMD.

He said south India, eastern coast and the northeast will continue to get rain over the next few days. The monsoon's performance so far has been below normal, with the countrywide rain deficit currently at 5.5%. The figure is unlikely to change much in the next three days, when the monsoon season (June to September) ends. This means that the monsoon is most likely to finish in the below-normal range (90-96% of long period average).

That would be a rather disappointing end to the season that had begun with expectations of normal rains. In April, IMD had forecast monsoon to be 96% of normal. It had subsequently updated the prediction to 98% of normal in June. Both forecasts had 4% error margin.

One-third of districts under rain deficit

Amit Bhattacharya, September 30, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

The overall monsoon shortfall is also showing in water storage levels.

In 2016, too, the monsoon went into a longish break in August.

A normal monsoon in 2016 had led to record foodgrain production.

India received below-normal monsoon this year, with the season ending on a 5.2% deficit on Saturday. While 50% of the country's districts have had normal rains, more than a third — 215 districts — are left with deficient rainfall, which could impact the kharif crop to an extent.

A 'below-normal monsoon', according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), is when countrywide rains in the season are 90-96% of the long period average (LPA). It is a category above 'deficient monsoon', when rains are below 90% of LPA (as in the drought years of 2014 and 2015).

The majority of the districts in rain distress this year are in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Vidarbha and surrounding areas, which were the hardest hit by an unexpected dip in rainfall in the second half of the season.

While the first half (June-July) posted a 2.5% rain surplus, August and September had a combined deficit of 12.5%. The Met department attributes the monsoon's failure in these months to a combination of factors that came into play together.

"A number of storms originated in the northwest Pacific in August, which reduced rain activity over the Indian subcontinent. Conditions in the Indian Ocean too did not boost rainfall during this period," said D Sivananda Pai, head of long range forecasting at IMD. In terms of India's four regions, the northwest had the maximum rain deficit of 10%, followed by central with 6%, and east and northeast with 4%. Rains were normal in south India.

The government's first advance estimate of this year's kharif crop reflects the monsoon's below-par performance, with the estimated production pegged 2.8% below last year's. A normal monsoon in 2016 had led to record foodgrain production.

The comparison with last year, when overall rains were better by just over two percentage points, is interesting. While 10 out of the 36 subdivisions in the country had deficient rains in 2016 — as compared to six this year — there were fewer districts with large rain shortfall. The number of districts with deficient or very deficient rain stood at 199 last year, while this year the number is 215.

In 2016, too, the monsoon went into a longish break in August. However, crucially, the break came later and lasted for a shorter time. This year, the break in the monsoon — when rainfall dips sharply in central India — began around July 26 and continued till the third week of August, a period crucial for kharif sowing.

"There were too many lulls in the monsoon during the second half. Also, the distribution of rainfall was rather poor, with some areas getting too much rain, which led to floods," said Pai. On the brighter side, south India got good rains during August and September, which wiped out the deficits of the previous months.

Some of these subdivisions, such as south interior Karnataka, had seen drought last year. The northeast, too, got good spells of rain in the second half. The overall monsoon shortfall is also showing in water storage levels. According to the Central Water Commission, 91 major reservoirs in the country were at 66% of capacity on September 28. This is just about 89% of the levels in the corresponding period last year, and 87% of the 10-year average.

Monsoon to end below-par as rains begin to withdraw

The southwest monsoon has begun to withdraw from the country , some two weeks later than normal.With just three days to go for the official end of India's rainy season, it is now fairly certain that this year's monsoon will end in the below-normal zone.

The India Meteorological Department announced on Wednesday that the monsoon had retreated from the western parts of Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan, as well as the northwestern tip of Gujarat.

“We expect the monsoon to withdraw completely from northwest India and adjoining parts of central India in the next two-three days. Dry weather is forecast in the region and there's a substantial drop in moisture levels, making conditions favourable for the retreat,“ said M Mohapatra, head of services at IMD.

He said south India, eastern coast and the northeast will continue to get rain over the next few days. The monsoon's performance so far has been below normal, with the countrywide rain deficit currently at 5.5%. The figure is unlikely to change much in the next three days, when the monsoon season (June to September) ends. This means that the monsoon is most likely to finish in the below-normal range (90-96% of long period average).

That would be a rather disappointing end to the season that had begun with expectations of normal rains. In April, IMD had forecast monsoon to be 96% of normal. It had subsequently updated the prediction to 98% of normal in June. Both forecasts had 4% error margin.

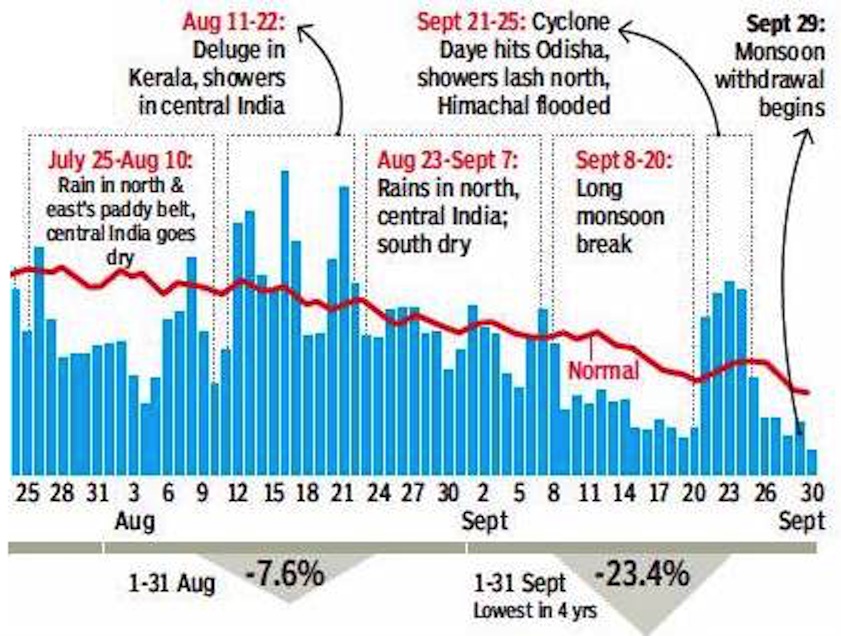

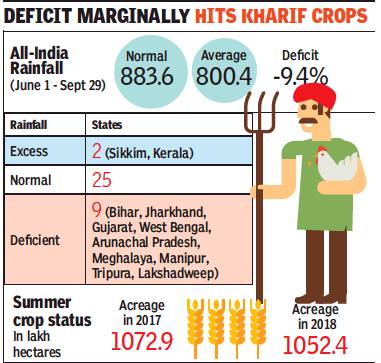

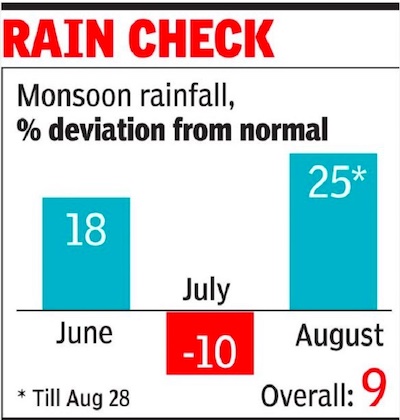

2018

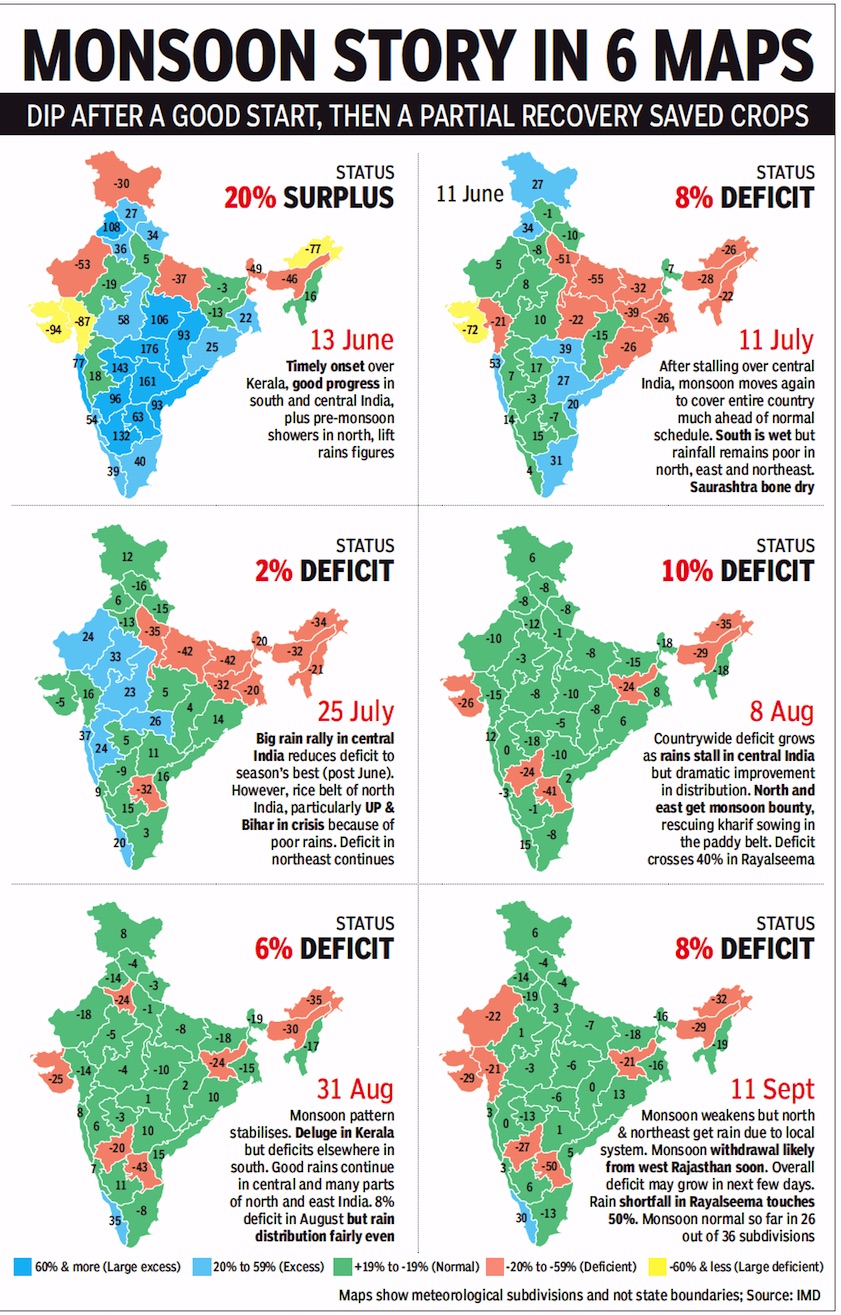

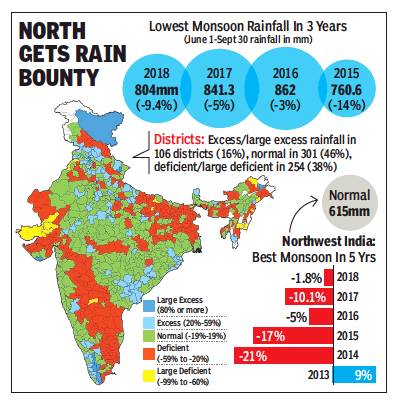

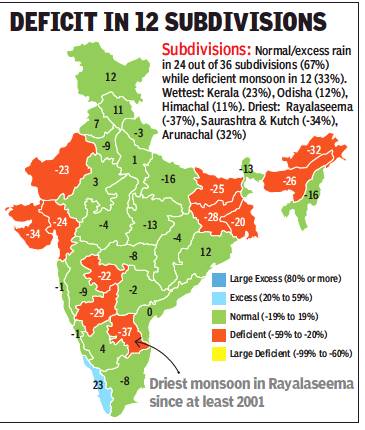

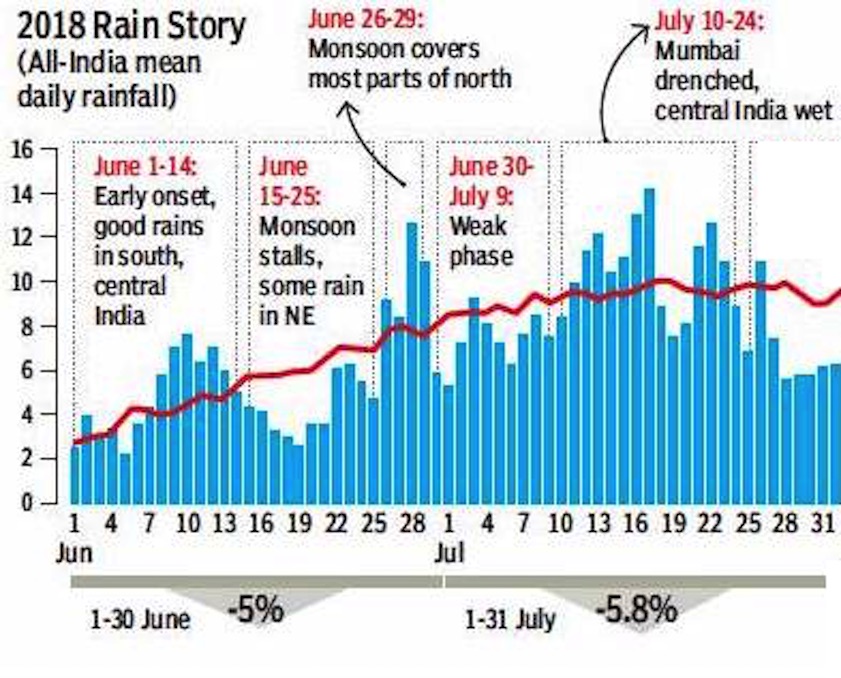

13 Jun- 11 Sept