Rajasthani folk music

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Langas and Manganiyars

Song of the desert

India Harmony Volume - 1 : Issue - 3 April, 2012

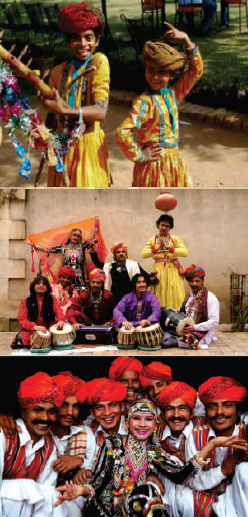

Songs like 'Nimbooda nimbooda 'and 'Damadam mast qalander' have become household tunes across the Indian sub-continent, thanks to Bollywood adapting and transforming these folk numbers. But, listen to Rajasthani musicians – these wandering minstrels sing these folk numbers in an earthy voice and that too in the midst of the Thar desert. Their musical resonance is electric and eclectic - an unforgettable experience.

Of the immensely beautiful states of India, each unique in its ethnicity and traditions, Rajasthan is probably the most mystically intriguing of all. The dullness of the desert, in contrast to its rich and colourful heritage, is a major enigma of this ancient land of great kings and fierce warriors. This exotic and vibrant land is also internationally renowned for its indigenous music and dance. Among its various music groups of this desert land, the most prominent groups of musicians are the Langas and the Manganiyars. Music is undoubtedly the most important aspect of their everyday life. The traditional folk music of the Langas and Manganiyars is the unique identity that it offers to these gifted desert musicians.

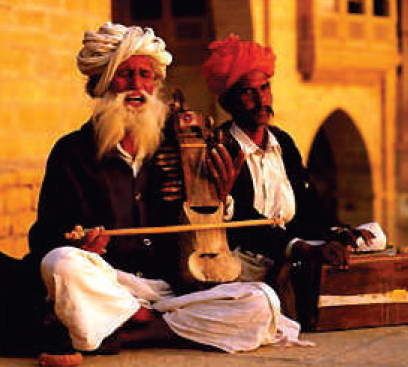

The Langas and Managniyars are Muslim folk musicians of Rajasthan, particularly Barmer and Jaisalmer along the indo-Pak border. Their music is indeed extraordinary and played with unique indigenous instruments. Listen to the marvellous notes emanating from the “kamaicha”, a stringed instrument that the Manganiyars play. It is virtuoso rhythm playing along with the “karthaal”, which comprises two wooden blocks held between fingers and deftly manipulated with hand movements, to create a staccato rhythm. The “karthaals” resemble castanets and the musicians create through them a distinctive melody as well as rhythm. Their 'dholak' is a hollow drum tapering at both ends which are covered with leather (animal skin). They use loops of rope to tighten the skin at the two ends.

Langas

The Langas are divided into two groups - one playing the “sarangi” as an accompaniment, besides, the “”dholak and ” karthaa”l. Langas who play the “sarangi” are known as Sarangiya Langas and those who play the aerophonic instruments like the “surnayi”, “satara” and the “Murali” are known as the Surnaiya langas. They also use the “morchang”, a kind of mouth harp. The music that emanates from their compositions is a series of wondrous songs chronicling life in the desert, complex compositions with inbuilt improvisatory rules, all honed over several centuries through oral tradition. This repertoire ranges from ballads about kings to sufi music and Meera bhajans. The music is full bodied , haunting , plaintive and sprightly by turns.

Patronised by aristocrats and wealthy landlords, the Langas and Mangniyars can be seen rendering songs at various stages of life, rituals and festive occasions - from child birth to weddings, to songs of bidding farewell to the daughter as she leaves her home after marriage. The traditional “jajman” (patrons) of the Manganiar are the locally dominant Rajput community, while the Langas have a similar relationship with the Sindhi-Sipahi, a community of Muslim Rajputs. Although the musicians are Muslims, their patrons are Hindus and many of their songs are in praise of Hindu deities and celebrate Hindu festivals such as Diwali and Holi. The musicians despite being devout Muslims, were never rigid. Their music is is eclectic, free, transcending barriers of language and religion, reflecting the same reverence for Allah and Krishna, using the “dholak”, the “khartal”, the “morchang” and the “kamaicha” with a unique vibrancy.

Besides praising God and the spirit of man in their music, these musicians also sing of nature and love; of the love of nature, and the nature of love. Their music captures the vibrancy of the Rajasthani landscape and is a standing affirmation to the syncretic culture of the Indian sub-continent. The result is a blend of two religions that is obvious from the names of the desert musicians, such as Shankar Khan.

Originally patronised by the Rajputs, it is the villagers in the countryside who are the new patrons of the folk music of Rajasthan,, actively participating in the shows put up by the travelling entertainers. Increasingly, domestic and international tourists are forming the larger audience for the Rajasthani folk singers.

The soulful, full throated voices of singers from these two music communities have filled the cool air of the desert night for centuries, in a tradition that reflects all aspects of Rajasthani life. Songs for every occasion, mood and moment; stories of legendary battles, heroes and lovers engender a spirit of identity, expressed through music that provides relief from the inhospitable land of heat and dust storms.

Says Prof Komal Kothari, who, has dedicated a lifetime to the revival of Rajasthani folk art: "I am amazed at how these simple folks have mastered their instruments, codified their craft and marketed themselves over the centuries. "And now, despite their initial reluctance, they have quite rapidly adapted to the new potential. They seek markets, travel the world, deliver professional performances and handle success with great suavity. I laugh when I hear of backwardness of India's unlettered masses”, he says.

Manganiyars

Seduced by the Manganiyars

by Priyanka Sacheti

Speaking over a crackling phone line from his native village Keraliya (near Pokhran, 80 km from Jaisalmer) Daevo Khan, Manganiyar musician and conductor of the acclaimed show 'The Manganiyar Seduction', explains the universe of Manganiyar musical traditions.

“The Manganiyar community has been singing songs since the time of Lord Krishna,” Daevo Khan begins, speaking in a mixture of Marwari, Hindi, and English. “Originally”, he explains, “they were known as Gandharvas, they were then referred to as Mir during the reign of Akbar, the Mughal emperor. They finally acquired their present moniker, Manganiyar, when princely states began to rule what is now Rajasthan; their name denotes the term 'to beg'.

That is because, although the Manganiyars are now a known folk musical community spread out in Rajasthan's Jaisalmer and Barmer areas performing a rich repertoire of ballads for their Rajput patrons, they once “played to appease the goddesses, and it is said that when we performed, even [the goddesses] stopped in their celestial chariots above to listen” says Khan. He adds that if goddesses themselves are happy with the music that the Manganiyars create, it is their hope that ordinary mortals down on earth too will be satisfied. Such statements reflect their syncretic religious identity; the Manganiyars are Sufi Muslims and yet sing songs in praise of Hindu deities with much fervor.

Daevo Khan wields the responsibility of being the conductor of The Manganiyar Seduction, a show by the acclaimed Indian director, Royston Abel, who has directed an award-winning production Othello in Black and White. Daevo initially met Abel in Delhi while working on Jiyo, a play dealing with out of work street performers. Then, when travelling with the production in Segovia in 2006, Abel once again met Daevo, who along with another Manganiyar artiste performed a new folk song every day for two weeks. “It was an absolutely intense encounter,” says Abel, “their music took me to a different place altogether, it was one of the most amazing experiences that I ever had.”

Abel was so inspired by their music that upon his return to India he came up with a new project. He went on to Jaisalmer where he selected 43 artistes from the three hundred odd who had auditioned and, in two weeks, created an initial version of what was going to become “The Manganiyar Seduction”. He presented it in Delhi as the opening act of Osian's Cine Festival 2006, which showcased a range of Asian cinema: the show was very well received, enabling him to garner more funding; he then spent a year and half structuring the full version of the show.

Combining the startling visual pyrotechnics inspired by the Amsterdam red-light area and the Hawa Mahal of Jaipur along with the Manganiyar performers' haunting music, the show has been described as a sensory feast. “We haven't done a show till date where we have not received a standing ovation,” says Abel who has presented “ The Maganiyar Seduction” all over the world. “I describe the show as a virtual whirlwind of sorts, working in spirals and completely immersing the audience into the Maganiyars' music. In other words, they experience what I did in those two weeks [in Spain],” he says, referring to his introduction to Maganiyar music. Abel is now working on a future project, The Maganiyar Longing, which will open in 2012. “The success of 'The Maganiyar Seduction' has become a parameter for me,” he says.

Describing his métier as that of working with traditional performers in a contemporary style, creating theatre in their music, Abel says that collaborating with the Maganiyars has been a memorable journey and that Daevo was the essential bridge between himself and them. “Apart from being the one who introduced me to the Maganiyars in the first place and being the best “khartal” player in the country, he also possessed a hunger in him to challenge himself,” says Abel to explain his decision to make Daevo the conductor of the show. “Also”, he says, “Daevo was in alignment with my vision and was able to communicate it to his fellow Maganiyars, thus, facilitating the execution of the project”..

Such innovative representation of folk and classical music performances is essential to attract audiences towards them, otherwise they may not have gravitated towards such music. “Folk maa hai, classical beta hain; folk se hi classical niklega [folk is the mother, classical is the son; classical ultimately originated from folk] says Daevo Khan, who has performed with many Indian classical musicians. “I performed alongside artistes such as Anindo Chatterjee on tabla and Ustad Shujat Khan on sitar,” says Daevo, who has also played along with Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Zakir Hussain. “I enjoy such moments a lot, I get inner peace while doing so.”

Daevo describes the Manganiyars' musical legacies as a gift of God which the community has nurtured and sustained over the centuries. “When we visited America, scholars asked us how is it that even a small child is so easily able to pick up the musical traditions. I said that when a pregnant woman sings, the child absorbs it through the womb and thus [the child] arrives in the world, virtually, crying in tune,” he says. His eleven year old son is already an accomplished artiste and performed abroad twice. Manganiyar women also sing, and two of them participate in 'The Manganiyar Seduction'

“I am dedicated towards ensuring that our music remains traditional and uncorrupted; I have heard ten generations worth of music and would like to preserve it,” he says in an oblique reference to many folk singers and musicians, who have migrated to Bollywood.

Daevo is presently absorbed in creating a new show, Folk Rajasthan, which will use traditional folk percussion instruments as its basis. Another project that he is working on has to do with Virah or the pathos of separation. In it, there is an attempt to convey the intensity of that emotion through music. Apart from time devoted to conceptualizing shows and performances, Daevo Khan has also established Swaroop Musical Institute in the premises of his own home in Keraliya where he teaches orphaned children showing inclination for learning music from his and surrounding village.