Ram Leela, Ramleela, Ramlila

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Agra

Muslim actors

In Agra, Nizamuddin continues to rock the Ramlila stage. He's been doing key roles for the last five years and is this time essaying the role of Janak, the father of Sita no less.

It wasn't always that easy for Nizamuddin though. During his early years in the Ramlila theatre, he too faced protests and opposition. But he stood his ground.

In fact, another Muslim will play the part of Bharat alongside him [in 2016].

The 55-year-old, who is a trackman at Agra Cantonment station in the north central railway zone, never took any acting classes but has been bagging top-notch roles since 2010.

Speaking to TOI, Nizamuddin said, “Getting a role in the Ramlila has always been a matter of pride for me, but things haven't been easy... scores of people from my own community raised questions about my faith in Islam. I was almost thrown out. I believe that there is no sin in a Muslim man acting in a Hindu play. After all, Ramlila talks about peace and the triumph of good over evil.“

Aishbagh

See Aishbagh

Delhi

The Luv Kush Ramlila

The Times of India, October 18, 2015

Dharvi Vaid Months of effort go into the staging of a Ramlila. TOI takes a peek backstage

Gasps and cheers fill the ground when Ganesha appears in the night sky in a psychedelic burst of light. Dancers in shiny , colourful costumes keep step as a hydraulic crane lowers the idol to the accompaniment of a live bhajan. The crowd is on its feet humming Ganesh Vandana while tiny, piercing phone flashes go off all around. The night is off to a successful start at the Luv Kush Ramlila outside Red Fort. The legend cannot change, but every year the many Ramlila committees in the city vie to outdo each other in its treatment. Ramlilas get bigger and, arguably , better. And this year's Lav Kush Ramlila--now in its 37th year--is the biggest ever. Mounted with a budget of Rs 3 crore, it has 30 television and Bollywood actors in the cast, special effects and stunts never seen before.

But it's one thing to plan big and another to ensure that the show runs as planned. And that means starting work months in advance. It is impossible to tell from the effortless scenes how much work has gone into making them possible. TOI goes behind the scenes to give you a peek into the making of a mega Ramlila.

The Luv Kush Ramlila Committee, which organized its first Ramlila in 1979, starts planning the year's theme and new elements in January , followed by decisions about the design of sets and the look of the artistes. Then comes the shopping in Sadar Bazaar. “It takes months to shop because we have to buy everything from the dresses to the props,“ says Sanjay Sharma, who runs the show backstage.

The best actors have to be engaged early . This year, they have hired 70 actors and 15 dancers.“Most of them come from Filmistan in Karol Bagh and are seasoned Ramlila actors,“ says Lovekesh Dhaliwal, assistant director of the show and a 12year veteran.

Auditions follow and roles are assigned, but the actors don't go into dialogue boot camp until a month before Navratras.“It is not television. There are no breaks, cuts and edits. We perform live and so there is no room for er so there is no room for error,“ says Dhaliwal. Some dialogues run into pages and are peppered with Sanskrit slokas. Voice modulation is the key to keep them from becoming boring monologues.

“To play a rakshasa, you need a booming voice that strikes fear in the audience; for a positive role it has to be deep but mellifluous,“ says Sunny Verma, who is playing Lakshmana.

Most artistes are not pros. They have day jobs but are passionate about acting. Which explains why they put in weeks of labour for a pittance. “We get only about Rs 10,000 for the entire Ramlila, but do it as an act of devotion,“ says a woman artiste who has been in Ramlilas for the past 10 years. Verma is a supervisor in a private firm. “I try to finish my work early so that I can come here and practise,“ he says. It's tougher for actors who play multiple roles.

Dhaliwal stays backstage but as the prompter he keeps the show ticking over when artistes falter.The Ramlila actors still don't use in-ear devices.“Goof-ups happen all the time. The lights and the audience make actors nervous,“ he says.

Kumar Gowda, who worked with BR Films in the hit TV series Mahabharata, is the stunts and special effects whiz. “I have worked with Rajinikanth and Kamal Hassan but a live performance is a different kind of challenge. A Ramlila action sequence is about magic, and fire and aerial acts, not fistfights.“

Gowda has brought equipment and professional stuntmen from Mumbai and has several scenes t e a l e r s lined up. He will show Ahilya transform into a living person from a statue, Hanuman fly over the audience and Meghnad appear at different places in mid-air using spotlights. The audience has already seen a stuntman on fire. Dangerous acts have made strong harnesses, safety mats, sand, water and fire extinguishers musthaves on the stage.

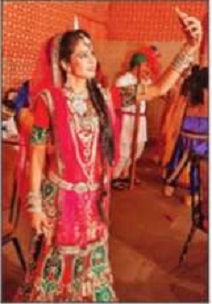

Costumes are as important as artistes and props in bringing alive a performance. The Luv Kush Ramlila has 18 trunks full of clothes and jewellery, and a resident tailor for last-minute fixes. “Each lehanga costs from Rs 5,000 to Rs 10,000 depending on how ornate it is,“ says Nandita Rani, one of the two women who look after costumes. The Ramlila has about 40 female artistes.

There are four makeup artists for the cast. One of them, Sumit Kumar, was to play Rama before TV actor Gagan Malik was roped in for the role. The Ramlila look requires thick coats of foundation and swatches of lipstick. “Makeup has to be bright enough for the expressions to be visible,“ says Kumar. And it has its nuances too. “The tilak has to be different for different characters. Lakshmana's eyebrows have to be defined and sleek while a rakshasa's have to be thick and drooping.“

Stunts and fine acts draw crowds but a Ramlila is also a night out for the audience, and it's incomplete without a `mela' atmosphere. There have to be rides and eats and knickknacks, and the grounds of the Luv Kush Ramlila have it all, from Ferris wheels to faluda. The curtain comes down late at night but when children return home armed with toy bows, arrows, swords and maces from the mela, the show resumes at home in the morning.

Shri Dharmic Lila, estd. 1924

As in 2018

From: Avijit Ghosh, Food showstopper at this Ramlila, but the pricey ‘piaos’ won’t quench thirst, October 13, 2018: The Times of India

Walking into Sri Dharmic Lila at Parade Ground opposite Red Fort — one of the many Ramlilas staged in the city — you immediately know it’s going to be a smorgasbord of the senses. The first banner that catches the eye announces Prabhu Dayal Sharma’s makhan samosa. Over the years, one has gorged on a variety of the all-time snack. Sometimes the stuffing is potato, occasionally cauliflower or keema, and even dodgy chowmein. What’s common is the outer layer made of maida or refined wheat. But Sharma, peddling this innovative version for the past 38 years, is a gamechanger. He has turned samosa into a dessert, altering both the inner filling and the outer coating. The casing consists of butter and the innards cashew, almonds and other nutty buddies, served after a sugar shower.

The makhan samosa is simply a teaser trailer. A few yards away inside the air-conditioned food shamiana, roughly the size of two tennis courts, lies a culinary wonderland of north Indian vegetarian fare. Entry is free but you need passes to get in.

Here you can watch roomali rotis being whirled in the air like frisbees. And you can gorge on fruit kuliya, an assortment of hollowed out fruits washed with lemon juice, stuffed with pomegranate seeds, sprinkled with chat masala and topped with grapes.

The foods stalls are a gourmand’s playground. Men in bush shirts and women in shimmery saris wolf down golgappas, the tangy water smelling subtly of pudina and heeng. Others gorge on exotic kulfi items like santre ke andar sharifa (custard apple tucked into oranges). For the less adventurous, there’s the usual too: pao bhaji, cheela, dal bati churma, mattar korma (you heard that right!) and more.

The treat isn’t cheap. The fruit kuliya costs Rs 300. But Sri Krishna Gupta, who owns the catering service, insists that the fruit assortment is a complete meal. “We are also providing the visitors good food in an air-conditioned, pollution-free environment. Compare our price with the cost of a family meal at any decent restaurant,” he says. And judging by the number of Rs 2,000 notes that effortlessly emerge from obese wallets, the price doesn’t seem to be a deterrent.

The food is the showstopper. The Ramlila area, with its dancing strobe lights, is the least crowded. Barely 20% of the seats are occupied. On stage, three armed and dangerous demons bully a group of orange-robed mendicants.

It’s a perfect October night, cool and friendly. Every year this part of Old Delhi turns into a playhouse of religio-cultural revelry that attracts lakhs during the Navratras. The origin of Shri Dharmic Lila goes back to 1924. Over the decades, it has hosted Delhi’s crème de la crème. The Viceroys came during the British Raj. At its office, you see photographs of the distinguished post-independence visitors: Nehru, Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, Shastri, Vajpayee, and others.

“We try to balance tradition with the modern,” says Dheeraj Dhar Gupta, general secretary, Shri Dharmik Lila. This is evident in the way the ‘piaos’ have evolved. Generally, ‘piaoos’ are known as places that serve drinking water. “At the ‘piaos’ in the Ramlilas, a particular group of families would set up a tent to watch the festival unfurl over 10 days. This was to ensure privacy of the family and the safety of kids,” explains businessman Narendra Kumar Gupta.

The modern ‘piaos’, about 30 in number, have morphed into self-contained air-conditioned units for the affluent with sofas, personal caterers for snacks and a private view of the Ramlila from the balcony. A small piaoos costs about Rs 1 lakh; the larger ones much more.

It is a festival and a fair rolled into one. Stalls hawk gaudy bows and arrows, plastic masks and maces. There are cheap toys, too. Also, the mandatory giant wheel, a dragon train and the swinging Columbus that scared and delighted a generation of Delhiites at Appu Ghar, now dead and buried.

The actors’ day jobs: politicians, film stars, housewives…

Like the characters they portray , the actors in the various Ramlilas across the city too are a colourful lot, each with his or her own little tale. Like Chandni, who becomes the demure Sita every evening at the Shri Nav Dharmik Leela Committee's show on the Red Fort lawns. In her sixth year as Lord Ram's wife, the English honours student of Swami Shraddhanand College is not alone here. Her mother Sapna is essaying the part of Kaikeyi, while her father daubs greasepaint on the cast members. While she loves her time on stage, Chandni is wary about telling friends about the alter ego she assumes on these 11days. “Some people don't consider the Ramlila to be a highclass affair,“ she said with a rueful grin. She said she initially found it tough to balance acting with academics, but after her multiple appearances, she no longer has to memorise her lines anew.

Also at the Ramlila gro unds is a troupe from Moradabad, from where actors have faithfully come for Shree Ramlila Committee's presentation every year for decades. “I was in the first team that arrived in 1966 and I have been coming here ever since,“ said Dr Pradeep Sharma, chief director of the mandali. Among his charges are Bharti Singh, 20, a political science student in Delhi University , who transforms into Sita, and Arpit Gupta, 24, an MBA graduate who handles cargo and international freight in a private company , in the role of Ram. Like the pair, the others too are well versed in Moradabad's distinctive form of acting called `Muradabadi shaili'.

For the fare at Indraprastha Ramlila Committee, the characters are mostly art and dance teachers from Delhi schools, all trained at the Bharatiya Kala Kendra. Rajni Shakya, the Sita in the version here, is Pandit Birju Maharaj's granddaughter and an accomplished Rajasthani folk dancer. “Kala (art) is a shared heritage in the family ,“ she said. “My sister Madhu is acting as Kaikeyi. There are the 10 days we dedicate every year to Lord Ram.“ While aspirants like Chandni and Bharti Singh hope to build on their Ramlila performances to step into professional acting, the Luv Kush Ramleela Committee has been bringing Bollywood and TV actors to portray the mythological characters. Ashok Agarwal, the committee chairman, said that it was less the need for glamour and rather efficiency and professionalism that made them decide on this route two years ago.

“This is the first time I have taken on the role of Sita in front of a live audience,“ said movie actress Gurleen Chopra. “I was initially nervous, but am enjoying it now.“ As for experiences on stage and camera, she said, “There are no retakes here. You have to practise hard to perfectly deliver your scene in one take.“

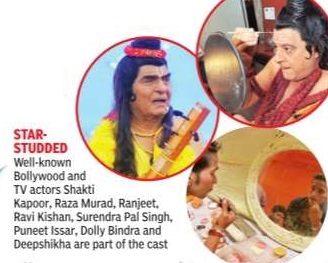

There are 55 movie and TV actors keeping Chopra company this year, including Film and Television Institute of India chairman Gajendra Chauhan, Manoj Tiwari, Ravi Kishan, Asrani, Shakti Kapoor, Raza Murad and Anoop Jalota. Why even former cricketer Manoj Prabhakar is striding the stage in the garb of Indra!

The Muslim contribution

Paras Singh, No Lakshman rekha for these Muslims. Oct 08 2016 : The Times of India

The first Ramlila group in the capital was set up [around A.D. 1850] by Mughal king Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Shri Navyuwak Ramleela

“I started at five by joining Ram's vanar sena,“ chuckles Sadiq Hussain, having graduated to bigger roles. For 15 years now he has been assigned the role of Lakshman in Shri Navyuwak Ramleela Committee's mythological.

Sporting a vermillion tilak, Hussain, 30, a resident of Kashmiri Gate, says, “I have never faced any problem here.The organisers as well as my family have always supported me.“ When he got married a month and a half ago, Hussain wondered whether he should be preoccupied with the Ramlila so soon after marriage, but his wife firmly put him in place by telling him, “You've been doing it for so long, why should you stop now?“ A couple of days ago, his wife and mother inaugurated the Sita swayamvar act by igniting a lamp. His brother Manzar Hussain used to act the role of Ravana.

Sri Nav Dharmik Ramleela

Mujib-ur-Rahman,27, Kumbhkaran at the Sri Nav Dharmik Ramleela, shared a similar experience. “I felt mummypapa would not let me act, but they did. I once lied and told them I was acting as Ram wondering if they'd let me play a Hindu god. But they had no problems.“

Luv Kush Ramlila

Jalaj Sharma, Hussain's director, says that Muslims participating in the Ramlila hasn't been a problem in Delhi.“And by Lord Ram's blessings, it will remain so in future,“ stresses Sharma. His optimism is founded on the ready acceptance of Muslim as artists, craftsmen and organisers of the capital's Ramlilas.Why , the star-studded Luv Kush Ramlila on Red Fort lawns has three prominent Muslims: Raza Murad as Janak, Farheen as Sunaina and Ali Khan as Meghnad. Ashok Agarwal, chairman of the committee there, points out that Muslim families of Old Delhi generously donate to these annual shows.

“Ramayan jodne ka kaam karti hai,“ says Hussain. [The Ramayan brings people together.]

Urdu Ramleela

Narendra Batra, 1976

Malini Nair, An epic story: Age-old Ramlila retold in Urdu, December 17, 2018: The Times of India

From: Malini Nair, An epic story: Age-old Ramlila retold in Urdu, December 17, 2018: The Times of India

Kisi ki rehti nahin hai yaksa misl-e-shams-o qamar samajh lo/Jivaal hota hai chand ka jab to roshniy-e-sahar samajh lo.

As the audience cheerfully chips in with wahwayi at the end of that couplet, you could be forgiven for thinking that you have walked into a mushaira. But laid out ahead, in its entire kitschy splendor, is Ravana’s court in Lanka, all red and brocade, dancing girls, the swaggering demon king himself and Hanuman, armed with a mace and tail that has a mind of its own.

Yes, this is Ramlila and Ramlila in Urdu. And Hanuman is ticking Ravan off in no uncertain terms for kidnapping Sita ( Janaki le aaye ho, jaan lekar jayegi). Remember that power doesn’t last forever, when the moon is at its lowest, it is time for luminescence, he tells Ravan.

Ramlila, just like Ramayana, is rich with multiple tellings. And even if BR Chopra set it in the matashree-pitashree variety of faux-Sanskrit context, it actually is told as a people’s epic — in local dialects, incorporating local cultures and even local geographies.

This Ramlila in Urdu, scripted by Narendra Batra in 1976, was presented in Delhi on Saturday at the annual Jashne-Rekhta festival, dedicated to Urdu and its abiding presence in our life. It has been staged by Shri Shraddha Ramlila annually in Faridabad’s Sector 15 for the last 11 years. Before that it was the staple at Palwal, Haryana for over 15 years.

“Batraji’s family, our family and that of many of our audiences were refugees from Pakistan and they brought with them the memory of the Ramlila that played there, replete with sher-o-shayari, but strictly faithful to the basic text,” says Anil Chawla, director of the play for the past 11 years. He started small in the play, graduating to Lakshman and still retains his character, forever humble and loyal on stage.

Almost every single character holds forth in Urdu in this Ramlila, nearly 70% of the lines, dialogues as well as poetry, are set in the language, estimates Chawla. But the biggest bulk of it, and the most thundering lines that bring on the applause and laughter, are set in Lanka as Ravana, his brothers and Hanuman face off in a mighty verbal joust of sher-oshayari. There is also liberal use of Urdu in sentences that are otherwise set in “chaste” Hindi. All this with a sprinkling of Tulsidas’s chaupais from Ramcharitmanas in Avadhi, the languages easily fitting into their own place.

“We all get to speak Urdu, even Lakshman. Sample this line he delivers to Bharat when he mistakenly berates him for eyeing Ram’s place on the throne: Kutil neeti teri tujhko yahan khench layi hai/ Mukkammal raj karne ki hawas dil mein samayi hai (your evil plans have brought you here, the thought of becoming a king deep in your heart). We are constantly switching languages,” says Chawla.

The play, he says, is hugely popular in Faridabad, drawing a daily crowd of 5,000 during Ramlila for its dialoguebaazi and unusual linguistic palate. It has also managed to travel to Prithvi Theatres in Mumbai as an eclectic theatrical work.

It is hard to pin the precise provenance of this script. Most Ramlilas in the Hindi belt claim their roots in the work of Radheshyam Kathavachak, composed in the first quarter of the 20th century. Scholars say this version underwent many revisions that ended up Sanskritising the text and scrubbing it of the Urdu/Arabic/Persian elements.

Chawla says it is originally the work of one “Yashwantji”, who could well be Sardar Yashwant Singh Verma Tohanvi born in late 19th century. His Ramlila is believed to have been popular in many parts of Haryana. But as is often the case, this Ramlila absorbed the influences of its script writer and the demands of its audiences even as it borrowed freely from modern Parsi and folk theatre styles.

For the Jashn-e-Rekhta audiences, just recovering from the subtly angsty sher-o-shayari of young poets, the theatrics of Ramlila in Urdu was a vast and very amusing jump. After all, how often do we get to hear Ravan standing arms akimbo ticking Hanuman off for his cheek in this wonderful mishmash of tongues: Ajab haivan mutallik hai, mera apman karta hai/Hamsari karta hai, talwar se khanjar ho kar (this is strange creature who insults me, thinks he equals me, as if a dagger could be what a sword is).

Kheriya (Firozabad)

In Firozabad district's Kheriya village, the annual Ramleela is funded and enacted with a great deal of enthusiasm by Muslims. The man playing Ram, Shamshad Ali, does the ritual Islamic wazu before he steps on to t h e ramshackle stage at the local Shiva temple. The props and costumes come from local Muslim homes as well, the curtains from a daadi, and the blouse from a naani.Jokes pepper the staging. An extra in a state of trance is beaten up with the question: “Tu Hindu bhoot hai ki Musalman? Bata...bata.“

The Times of India, Dec 06 2015

Malini Nair

Spicing up Ramlila with thumkas and qawwali

In Firozabad's Kheriya village, the Ramlila's primarily Muslim cast combines humour, dance, music & acrobatics Shamshad Ali does the wazu, the sacred ablution, and heads for prayers at the village masjid, and in the next instant he stands on a ramshackle green room in the courtyard of the Hanuman temple transformed into Ram. He is among the many Muslims of Kheriya, a village in the glass-making district of Firozabad, UP, who enthusiastically join the unique Ramlila performance every year, telling the epic over 17 long days. Ramlila everywhere is highly folksy in nature, with elements from nautanki and Bollywood thrown in for good measure. But nothing will prepare you for the total riot that is Kheriya Ramlila, recently performed at the IGNCA in Delhi. And the creative camaraderie that marks the production is unfettered by any communal sentiments.

“All the major characters are played by Muslim males. The village audiences don't really care about religion -they just found the talent they needed to play Ram or Hanuman or a dholakiya or acrobat. In fact, they are not even beyond lampooning the whole Hindu-Muslim debate,“ says Molly Kaushal, professor, performance studies, at the IGNCA.

Kheriya Ramlila is totally owned by the people of the village, written up as they want, played on the artistic whims of the cast, dotted with humour, satire and impromptu acts. There really is no script here to talk of, though the play is based loosely on Radheysham's Ramayan, the text used by Ramlilas across most of the Hindi speak ing belt. For the rest, expect the unexpected.

Midway through the play , Sunil Kumar, a cross-dresser, enters the stage and asks the rag-tag bunch of characters trying without much luck to summon the devi in their midst: Is this how you tempt her to earth? Let me show you how. And breaks into some wildly provocative thumkas that has the crowd in splits. There is even a passing comic sutradhar, who is allowed every liberty including bursting into a Kishore Kumar qawwali -Haal kya hai dilon ka na poochho sanam.

Nothing much is sacred on this dais where Ram, Sita and Laxman sit patiently suffering the goings-on. Even when they enter the picture there is no stopping the gags. Sunil Kumar, now Soorpanakha, is ogling at Ram who tells her: “Devi, main shaadi shuda hoon.“ “Mujhe devi mat bula, woh to mandir main baithti hai. Mujhse direct baat kar,“ she saucily retorts.

Most of the actors are farm hands, labourers, and those who do assorted jobs. For them the yearly show is a break from drudgery. Kheriya Ramlila is a creation of the 1970s. Up until then the village had to troop to neighbouring Ramlilas. What they had, however, was swang, a popular folk form that involves mimicry, a whole lot of clowning around, jokes, songs and dance. The swang troupe once tried its hand at doing Ramlila and the show went so well the village decided to put its spare resources to staging it every year at Dassera.

Humour still remains a big element of Kheriya Ramlila. An extra in a state of trance is being beaten up with the question: “Tu Hindu bhoot hai ki Musalman? Bata...bata..“

Soon an Aghori baba you are not likely to see at any Ramlila joins the action, straight from the shamshan bhoomi, painted in the grey of the ashes and red of the pyres. Exactly what is he doing in the middle of divine storytell ing? Nothing much, but it is scary and jolly good fun. Ram, Sita and Laxman seem to be having a good time too.

Malabar/ Mappila Ramayanam

Malini Nair, When Ramlila begins with a wazu, Oct 09 2016 : The Times of India

Among the most fascinating Muslim interpretations is the Mappila Ramayanam of Kerala's Malabar region. It is hard to trace its historicity or even authorship of these songs, but sometime in the early 1930s, a Brahmin teen had become an ardent fan of a Malabar Muslim minstrel, nicknamed `pranthan (lunatic) Hasankutty'. He memorized 148 lines of a lyrical mish mash that later came to be known as Mappila Ramayana paattu (songs). The teen became a leading Kerala folklorist TH Kunhiraman Nambiar. His collection of Malabar Ramayana ballads merrily dip into the local culture and even weave in contemporary ideas into the telling of the story. “The Mappila Ramayan am is replete with images and expressions alluding to the Muslim way of life such as kozhi (chicken) biriyani, beevi Shurpanakha etc,“ says scholar Azeez Tharuvana in his acclaimed work Wayanadan Ramayanam (the Ramayanas of Wayanad).

The Muslim references are often integrated into the Ramayana with humour. For instance, Shurpanakha exhorting Rama to accept her cites the Shariya on why he doesn't have to stay faithful to one wife.

Tharuvana believes that Ramayana in these cases becomes more of a cultural, rather than religious, text. “Just as the adivasis of Wayanad have turned the story of Rama into something set in their hills and villages, the Mappila Ramayanam sets itself in the context of Malabar Muslims. The Indonesian Muslims have done this with Hikayat Seri Rama so have the Malaysians and Filipino Muslims,“ he points out.

Mewat/ Meo jogis

Malini Nair, When Ramlila begins with a wazu, Oct 09 2016 : The Times of India

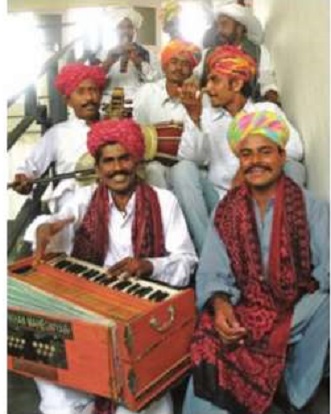

Ever since he can remember Umar Farooq Mewati has been singing Lanka Chadhai, a ballad in praise of Ram's triumph over Ravana. He belongs to a band of Muslim minstrels called Meo jogis who are often invited by Muslim jajmans (patrons) in and around Alwar in Rajasthan to perform on festive and family occasions.

But in recent years, Mewati and other Meo jogis have been finding it hard to hang on to their art. “We have been hit by the increasing kattarvad (fundamentalism) in the region among both communities -Hindus as well as Muslims. Hajis are now telling us that music is haram; some of them tell us to take the money but leave without singing. This is an oral tradition, if we don't practise it, it will die,“ says Mewati.

A nostalgic Siddiqui who was to play Marich in his village Ramleela in western UP, was forced off the stage by the shrill racket of the local Shiv Sena. Sena men claimed that no Muslim had played roles in the Budhana Ramleela for decades. But across UP -especially in Kanpur, Lucknow and Muradabad -there are several living and thriving examples of Muslim participation in amateur Ramleelas.

Moradabad: a unique tradition

Paras Singh, Why city Ramlilas like the Moradabadi twist, September 27, 2017: The Times of India

Amitosh Sharma was just nine years old when he left his home in Moradabad to travel to Delhi with a troupe of Ramlila actors. He didn't have much of a role, just a quiet part as a soldier in the Vanar Sena. But he was excited to be at the famed event organised every year on the grounds at Red Fort. After 50 years, that excitement of childhood abides, though Sharma is no sprightly simian soldier now, but a director of one of the most elaborate Ramlila shows in 2017.

Sharma has travelled re gularly to Delhi since then.Over 700 Ramlilas, big and small, are organised at Dussehra every year, and the actors of Moradabad are preferred. They bring their own professional rigour, observing strict vows of brahmacharya, sleeping on the ground and abstaining from anything considered ritually impure during the 10 days they stride the stage as characters from the Ramayana.

The annual enactment of the Ram legend is now categorised according to the stylistic approaches of the `mandalis' that perform it.But the Moradabadi shaili, or style, has trumped those attributed to Ayodhya, Brijbhoomi and Mathura. Sharma's troupe too depends on the distinctive playback method of the Moradabadi tradition. As Dr Pradeep Sharma, 65, who heads the Adarsh Kala Sangam, explained, “Moradabad mastered the style of having the actors' dialogues voiced by special voice artistes from behind the stage.“ Also, it was the Moradabadi associations that first allowed women to play the females roles.

This year too, actors from Moradabad will be in the limelight in most of the important Ramlilas in the city , such as those organised by Sri Dharmik Ramlila Committee at Madhavdas Park, ShreeRamlila Committee at Ramlila Ground and Nav Sri Dharmik Ramlila Committee at Red Fort. Many of the performers are professionals, who leave their corporate duties aside for 10 days to take on mythological personas. So Arpit Gupta, 24, an MBA graduate who handles international freight for a private company , is Ram at one show, while pharma company manager Anuj Saxena dons the Ayodhya scion's mantle in another.

Moradabad has hundreds of mandalis that churn out new talent every year. Organisers, who have brought around 45 such troupes to Delhi this year, say that the diction of the voice actors is soft and their tongue is well trained for the nuances of pure Hindi. “We had earlier tried out the groups from Mathura too, but found that Delhiites don't like the Brij accent,“ testified Vijay Sarathi, head of the Sri Ramlila Committee at Ramlila Ground.

Sarathi added, “Delhi's people appreciate the flow and coordination between the voice artistes and the actors on stage.“ The synchronisation actually requires many months of intense practice to perfect. Hundreds had been rehearsing tireless in Moradabad for so many weeks so that when thousands of Delhi's citizens lined up to see the gods striding the stage, they wouldn't return home feeling unblessed.

Mumtaznagar Ramlila

The Times of India, Oct 19 2015

Muslims holding Ramlila here since 1963

For 50-odd years Mumtaznagar Ramlila here has exemplified inter-com munity goodwill. Held in a Muslim neighbourhood, this Ramlila has been managed and largely enacted by Mus lims. For two years, however Muslims have been barred from playing main charac ters like Ram, Sita, Laksh man and Hanuman. The rea son: they eat meat. “Some local people object ed to Muslims performing lead roles in Ramlila,“ said Majid Ali, president of the Ramlila committee.

“Their objection was that since Muslims eat meat, they shouldn't enact the role of gods. When we came to know about the objections, we eased them out,“ Ali told TOI. Baldhari Yadav, a senior member of the Mum taznagar Ramlila committee, said women spectators worship the actors playing Lord Ram, Lakhsman, Sita and other gods by touching their feet and seeking their blessings.

Keeping in view their re ligiosity, Muslims who eat meat have been replaced by Hindus who, even if they are meat-eaters, turn vegetarians during Navratra. “But Muslims continue to play smaller parts,“ Yadav said.

The Ramlila here has sustained the same zeal since 1963. Tailor Naseem, with his limited income, starts taking extra orders before Navratra to fund the 10-day affair. He is supported by other Muslims.

Muslims and Ram Leela

Mughal-ruled Delhi and Ram Leela

R. V. SMITH, Sep 13, 2009: The Hindu

With Dussehra round the corner, here is the history of Ramleela celebrations in the city from the days of Shah Jahan

Ramleela began to be celebrated in old Delhi when Shah Jahan moved his capital here in the mid-17th Century. Shah-ka-talab once occupied the site now known as Ramleela Ground. The lake served as a perfect setting for the Kevat scene in the Ramayana when Ram, Sita and Lakshman were ferried across the Saryu river by the boatman in the initial stage of their 14-year exile. The main Ramleela celebrations from the 17th to 19th centuries used to be held behind the Red Fort on the Yamuna bank, with the Moghul Emperor watching from the balcony in front of the Shahi Hamams of the fort.

The effigies of Ravan and his kinsmen first began to be burnt during the reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar (1837-1857), but the Ramleela had its own charm in the days of Mohammad Shah (1719-1748).

Whether Mohammad Shah came to Shah-ka-talab is not known but Bahadur Shah Zafar did. The lake was filled up after the 1857 uprising, though some say it was done earlier to facilitate the burning of the effigies there. Had the lake survived, Ramleela in Delhi would have been even more colourful. Just think of Ramleela on the Yamuna bank! The only bridge over the river then was the one of boats. People sat on them to witness the spectacle in its final stages. On Dussehra day the begums in the Red Fort were eager onlookers, craning their neck from palace windows to catch a glimpse of the effigies which were certainly not as tall as they are now. But it seems they were made by the same craftsmen from what is now Uttar Pradesh and a few local Muslims living in the lanes and by-lanes – the same ones who made the Tazias at Moharram time. For the paper and cloth used was of the same type and so also the bamboo frame. The crackers fitted into the effigies were the work of the atishbaazs from behind the Jama Masjid, were a few shops still survive. They were helped by the atish (fireworks) department that came into being during Shah Jahan’s time. When the effigies were set alight, the explosions were such that they could be heard right up to the farthest corners of the Walled City. As Kumbhkaran, Meghnad and Ravan faced their doom from the arrows of Ram and Lakshman, eager eyes watched to see them fall. Many held their breath because the belief was that the direction in which Ravan fell would have a harrowing time in the coming year.

One remembers Zubeda Begum of Machliwalan, looking out from a top window of her house towards Ramleela Ground in 1964, shouting to her friends that Ravan had fallen towards the Red Fort and so no harm would befall those on this side of the city. But one year, when the effigies were set alight on a Tuesday, Ravan just refused to burst into flames and it took all the skill of the atishbaaz to ignite the demon king angry that he, a Brahman, should face his end on a Mangal day. Or so they said!

Muslims’ Ram Leelas

In India, Muslims across regions have been retelling, singing and performing stories from the Ramayana as well as participating in local performances of Ramleela. The Muslim Manganiyars of Rajasthan tell Ram Katha as do the Muslim patuas skilled in patachitra in West Bengal. Most of the crafts associated with Ramleela in north India --the making of the Ravana effigy, the zardozi, mukut, costumes, the toy replicas of `weapons' -are all considered the domain of Muslim artisans.

PrayagRaj: Katra/ focus on Ravan

Rajeev.Mani, Sep 25, 2022: The Times of India

Prayagraj: The villain as a hero isn’t just the stuff of novels and film noir. Ravan, the archetypal bad man of Hindu mythology, ironically hogs the limelight in Lord Ram’s celebration of victory over evil in Prayagraj’s Katra.

First-time visitors to Katra’s annual Ramlila are surprised, if not shocked, to see the event is a nod to Ravan’s origins rather than the greatness of Ram, who vanquishes the demon king of Lanka. Be it the procession taken out in his name or the Ramlila organised in the locality, Katra leans towards Ravan because legend has it the place was his nanihal (maternal home).

In the Ramayan, sage Bharadwaj marries off his daughter Ilavila to fellow hermit Vishrava. The couple’s son Kuber, the Hindu god of wealth, goes on to become the original ruler of Lanka. Later, Vishrava marries asura Sumali’s daughter Kaikesi, with whom he has four children, the eldest being Ravan.

Uttarakhand

Shortage of suitable male leads/ 2019

Ishita Mishra, Nov 11, 2019: The Times of India

Gaurav Gairola, 20, has played the character of Ram in the Ramlila staged in Pauri since the past two years. However, from next year, the law student will be moving to Dehradun to practise in the district courts after finishing his graduation from the Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal-University. That’s another ‘Ram’ gone. And organisers of the 119-year-old Ramlila have gone through this over and over again.

In the hills of Uttarakhand that have been hit by migration, Ramlila organisers have been finding it difficult to get suitable characters to play the role of Ram and other central characters of the epic like Lakshman, Hanuman, Sita and Ravan. “Every year, someone from the Ramlila moves out in search of a job or education, and we are left scratching our head for a suitable replacement,” says Gaurishankar Thapliyal, 69, president of the Pauri Ramlila committee, concern writ large on his face.

For organisers of the Pauri Ramlila— which has been documented by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA), New Delhi, under its project to document oldest and unique Ramlilas of India — the struggle to get a good artiste is even more pronounced. This is because the Ramlila here is based on the ‘Geya Paddathi’ (singing method) — and the actors are required to also sing a bit. “There are no dialogues in the Ramlila — only ‘chaupai’ (couplets) and songs. We hardly get actors who can sing as well as act. As a result, we sometimes have to use voice-over artistes. It is a compromise with the original style that we are famous for, but what do we do?” says Thapliyal, who, in the absence of actors, has himself played various roles in the Ramlila in the past 45 years and currently plays Raja Janak, father of Sita.

According to the Uttarakhand Rural Development & Migration Commission, a body constituted by the BJP government in the state two years ago to find out ways to check the pressing problem of migration from the hills, Pauri is one of the worst affected districts in the state in this regard. The area has the maximum number of ‘ghost villages’ — 186 — which have been completely abandoned since their inhabitants left for towns and cities in search of better opportunities.

Ironically, a number of prominent personalities hail from Pauri — like chief minister Trivendra Singh Rawat as well as Army chief General Bipin Rawat. Former chief ministers Major General B C Khanduri (retired), Ramesh PokhriyalNishank and Vijay Bahuguna also belong to Pauri as does Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adityanath.

In Almora, another hill district, Ramlila organisers face a similar problem. At the Hukka Club’s Ramlila in Almora which like the Pauri one has also been documented by IGNCA as a unique Ramlila, children under the age of 14 years perform the roles of the main characters. This Ramlila, too, has been forced to compromise with its original form and take on adult characters to essay key roles. Tribhuvan Giri, 75, president of Hukka Club, says that it is a big struggle to get children who can enact their role while being also able to speak good Hindi. “The craze for English education as well as constant migration of people from the hills has hit our traditional Ramlila badly,” laments Giri.

In Almora, over 16,000 people have moved out of the district in the past few years as per the migration commission’s report, which states that over 52 % people who migrated from Almora have moved out in search of work. Giri sums up the situation when he says, “The government may build a grand temple at Ayodhya but what will they do about the missing Rams?”