School education: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

‘Boards’ of school education

International ‘boards’

2011-17: CIE, IB, ISC

From: Manash Gohain, As foreign boards gain ground, UK’s CIE set to overtake ISC, July 9, 2018: The Times of India

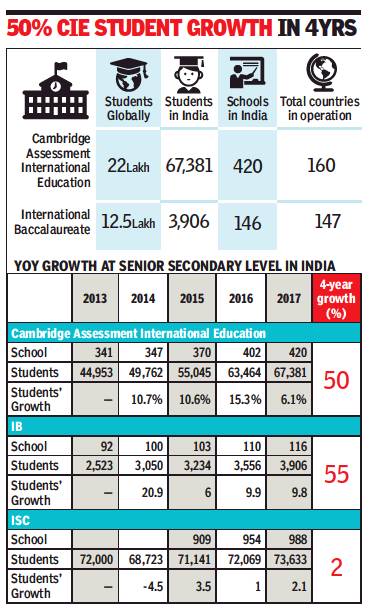

Indian students now aspire to a world-class education, as borne out by the remarkable growth of international boards in the country. In the last decade, especially the last five years, many more schools have been offering qualifications with global currency, like the International Baccalaureate (IB) and the Cambridge Assessment International Education (CIE).

With 10% year-on-year growth between 2014 and 2016, and another 6.1% in 2017, the UK-based CIE’s strength in India is now about 67,000, barely 6,000 students short of the number for the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (ISC). Meanwhile, Switzerland’s IB programme has also increased its presence from 92 schools in 2013 to 146 schools now.

Apart from offering international practices and academic standards, these curricula have also adjusted to the Indian academic calendar.

The Cambridge International Examinations (CIE), which has witnessed rapid growth in India, offers the option of a March examination exclusively for Indian students. These boards also offer a range of Indian subjects such as Sanskrit and Hindi.

With over 22 lakh students across 160 countries, CIE is one of the most popular international school curricula on offer. It now adds roughly 30 to 40 schools in India every year; from 340 schools in 2012-13, it has expanded to 420 schools in 2017.

But these international curricula come with a hefty price tag. Ruchira Ghosh, regional director for South Asia, CIE, said: “The cost is comparatively higher because of the investment it takes to create such a curriculum. It is really about value for money,” she said. Similarly, the IB programme has grown almost tenfold in the last decade. In 2003, a mere 11 schools offered the IB programme. By 2013, this number had gone up to 107.

This growth story also belies the general perception that that CIE or IB students go abroad for higher studies. The majority of these students, in fact, stay on in India for their undergraduate degree and do well.

“While top universities around the world accept the Cambridge qualification, our students are also going to the best of Indian universities. In fact, most of them study in India,” said Ghosh.

The buses of Schools

SC’s guidelines of 1997

Speed Limit Was Fixed At 40Kmph

The Supreme Court laid down elaborate guidelines in 1997 for school bus operations across the country to minimise risk to the lives of school children, months after a school bus plunged into the Yamuna at Wazirabad in Delhi and left 28 students dead.

Police and other authorities have blinked at schools operating buses without follo wing the guidelines. The SC had made it clear that only drivers with five years' heavy vehicle driving experience would be eligible to ferry schoolchildren, any driver booked twice for traffic-related offences was to be pulled out of duty.

Apart from that, the court had directed a series of preventive measures -first-aid box in buses, doors to be fitted with proper lock, fire extinguisher, horizontal parallel grills on windows, school bag tray under the seat and provision for water in school buses. Besides, it had made it mandatory for a supervisor, deputed by the school, to accompany the children.

In addition, the court on December 16, 1997 had ordered, “On or after April 30, 1998, no bus used or in the service of an educational institution shall be permitted to operate without a qualified conductor being present at all times.“

CBSE’s rules, guidelines

'Mandatory disclosures' for schools

CBSE extends deadline for 'mandatory disclosures' TNN | Nov 1, 2016, The Times of India

BHOPAL: Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) in its latest circular has strictly asked 991 CBSE affiliated schools in Madhya Pradesh including 95 from Bhopal [Indpaedia: this applies to all CBSE affiliated schools in India] to conform to its order to display all information regarding fees and expenditure on their websites latest by November 30 2016. Most schools have failed to adhere to the earlier order of the board.

Board had earlier issued an advisory to all its affiliated schools, asking them to share the fee structure along with details of all the facilities they provide by or before October 31. However, 90% schools as per sources in the state failed to abide.

The new order issued by the board, a copy of which is with TOI has asked the schools to upload all information on public domain latest by November 30, 2016, failing which action would be taken against defaulting schools.

Actions shall include cancellation of affiliation and barring such schools from getting affiliation in future. Under mandatory disclosure, the CBSE has asked for an expansive list which includes infrastructural details of the school including the plot size, the built up area, and the size of the playground.

Furthermore, schools are also asked about the number of buildings, details of the trust that owns them or their subsequent management. Besides, the most important revelations in the list include fee structure, salary of teachers with mode of payment, details of sexual harassment committee and personnel information including details of school management, teaching and non-teaching staff.

"All the schools need to comply with the latest orders and the deadline stands extended till November, 30 for mandatory disclosures," reads the official letter of CBSE issued to all schools in the state

No bus duty for teachers

Abhishek Choudhari, CBSE to schools: No bus duty for teachers, Nov 02 2016 : The Times of India

Nagpur:

The Central Board of Secondary Education has asked affiliated schools to limit teachers' duty within the classroom and employ “separate trained staff “ for activities like bus route supervision and canteen duty .

“For activities of ministerial nature, transport or canteen and other related tasks, separate trained staff may be deployed by school,“ an order by the central board ruled. According to the new rules, teachers can now reject such “administrative“ assignments.

In Nagpur, where teachers supervise bus routes to ensure students' safety, a private school principal told TOI that institutions appoint `route in-charge' keeping in view the safety of the school students throughout the journey . “Almost always the teacher's stop is either the last, or second last on the route. The bus contractor also puts a female attendant in most buses,“ the principal said.

Every bus has at least one and maximum four teachers aboard.“The regional transport office allows only up to four teachers in the bus as passengers, as the transport vehicle is primarily for stu dents and gets a heavy road tax subsidy . So basically these teachers are just travelling back home but we design the route in such a way that the supervisor teacher gets off at the last stop,“ another principal said.

A principal said supervising kids during break time is essential to avoid untoward incidents. “Kids can get into a fight and with no teacher watching over things can go out of hand fast. Lot of schools balance the workload by cutting down on the teaching hours for such teachers, so frankly no one can complain,“ a teacher said.

‘No sale of books, uniforms in schools’

Manash Gohain, No sale of books, uniforms in schools: CBSE, April 21, 2017: The Times of India

The Central Board of Secondary Education has asked affiliated schools across the country to shut down shops selling textbooks, stationery, schoolbags, uniforms, shoes and similar articles within their premises.

The board asked schools on Thursday to strictly comply with its affiliation byelaws and “not indulge in commercial activities“. This includes sales through “selected vendors“.

The directive comes on the heels of the board's effort to make schools follow NCERT textbooks and creation of an online link for scho ols to raise demand for these books in February this year.

The circular issued by CBSE on “commercial activities“ in schools said the board had received complaints from parents and other stakeholders on schools “indulging in commercial activities by way of selling of books and uniforms etc within the school premises or through selec ted vendors“ despite being asked not to do so.

“There is a nexus of profiteering. But our affiliation byelaws are clear that schools are a community service and not commercial entities. It is mandatory for schools to adhere to the provisions,“ said R K Chaturvedi, chairperson, CBSE. The circular asked school managements to strict ly comply with its directive.

The board cited “rule 19.1 (ii) of CBSE affiliation byelaws“ which mandates that managements shall ensure that the school is run as a community service and not as a business and that commercialisation will not take place in the school in any shape whatsoever.

CBSE said it had taken a “serious view“ of violations of this rule. “Schools are directed to desist from the unhealthy practice of coercing parents to buy textbooks... from within the premises or from selected vendors only .“

The board also reiterated that all affiliated schools are “required to follow direc tions given in its circular dated April 12, 2016, regarding use of NCERTCBSE textbooks. Often the board receives reports and com plaints regarding pressure exercised by schools on children and their parents to buy textbooks other than NCERTCBSE.“

Dropout level, year-wise

Out-of-school children: 2009-2014

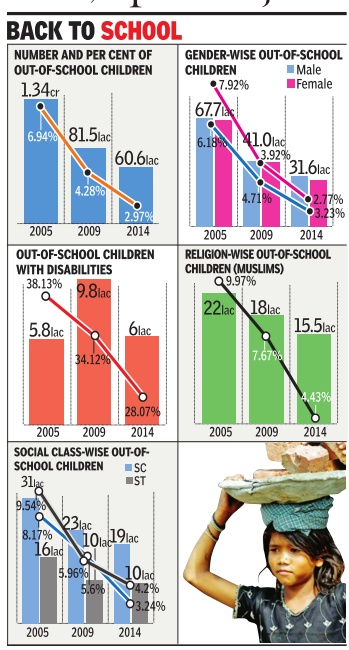

RTE effect: 26% drop in number of out-of-school kids since 2009

Akshaya Mukul

The Times of India Oct 14 2014

In a vindication of sorts for the Right to Education (RTE) Act, the latest HRD ministry-mandated survey shows a 26% drop in out-of-school children in the country since 2009.

According to the latest survey conducted by Indian Market Research Bureau for the ministry , out-of-school (OoS) children have declined to 60.6 lakh -2.97% of all children in the 6-14 age group -from 81.5 lakh in 2009. The first survey in 2005 found 1.34 crore out of school.

There were less girls (28.9 lakh) out of school than boys (31.7 lakh). In fact, girls have done better than boys in all three surveys.

A survey of OoS slum children was done for the first time and their number was found to be 4.73 lakh.

The survey found a continuing drop in the number of OoS children among Scheduled Castes and Muslims. Among tribal OoS children, the drop was marginal -from 10.69 lakh in 2009 to 10.07 lakh in 2014. In terms of social classes, the number of SC out-ofschool (OoS) children have come down to 19.66 lakh from 23.08 lakh in 2009 and 31.04 lakh in 2005.

In the latest survey found there were 15.57 lakh Muslim OoS children, down from 18.75 lakh in 2009 and 22.53 lakh in 2005.

While states such as Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Delhi, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal witnessed a decline in the OoS children, in 13 states and Union Territories percentage of such children has increased since 2009.

These include Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Chhattisgarh, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand.

What dampens the good work of RTE is that the decline in OoS disabled children has followed a different trajectory.

In 2005, 5.82 lakh disabled children were out of school which went up to 9.88 lakh in 2009 and in the latest round has come down to 6 lakh. Sources said it could be due to inclusion of more kinds of mental and physical disabilities in the list so that RTE becomes more inclusive. But there is a general acknowledgement that a lot needs to be done on this front.

January-July 2014: Dropout level

The Times of India, Jul 06 2015

Mahendra Singh

`11% of rural, 6% of urban people under 30 never went to schools'

Around 11% of those between 5-29 years of age in rural areas and 6% in urban areas never went to any educational institution, reveals an NSSO survey conducted between January and July , 2014. The students of the same age group who dropped out were around 33% in rural areas and 38% in urban areas. The survey has highlighted that the proportion of dropouts and `never enrolled' students depended on the living standards of households.The dropout rate was low in case of families with higher usually monthly per capita consumer expenditure (UMPCE). It was found that the proportion of the `never enrolled' category fell steeply from nearly 16% in the poorest households to only 6% among the richest in rural areas. In urban India, too, the percentage dropped from 12% to 1% from the bottom to the top class of households.

The survey found that the proportion of `never enrolled' persons in early 2014 had reduced by around 30% as compared to 2007-08.

However, it noted that the overall picture for proportion of dropouts, both in rural and urban areas, had not changed significantly over time as well as over UMPCE classes.

The survey revealed that the major reason for non-enrolment in rural areas was `not interested in education' (33% male and 27% female) while in urban areas, nearly 33% males and 30% females in the age group 5-29 years never enrolled because of `financial constraints'. The most common reason for dropping out for males was engagement in economic activities (30% in rural areas and 34% in urban areas), whereas for the females, the dominant reason was engagement in domestic activities (33% in rural areas and 23% in urban areas).

It noted marriage as second major reason for females (17%) to leave education in urban areas. The survey found that in rural areas, dropouts were mostly in the age-group of 5-15 years for both males and females. In contrast, in urban areas most dropout were in the age-group of 16-24 years.

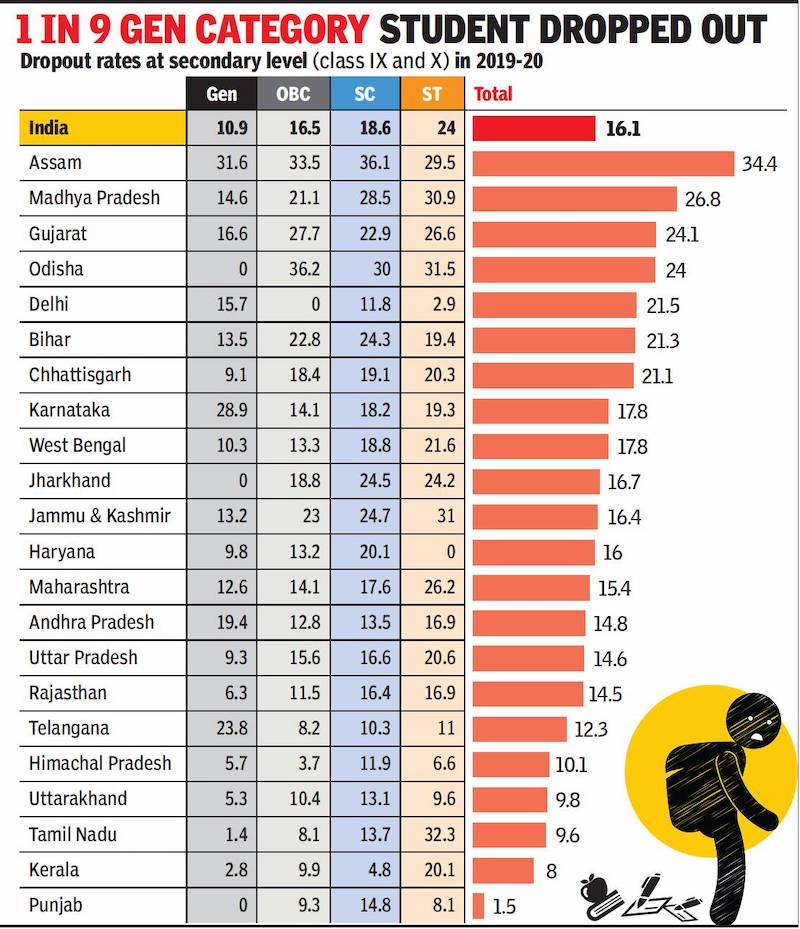

2019-20: dropout rate for SC, ST, OBC; class-wise

Rema Nagarajan, July 6, 2021: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 6, 2021: The Times of India

1/4th of tribals, 1/5th of Dalits quit Class IX & X in 2019-20

Nearly a quarter of tribals and a fifth of Dalits dropped out of school in classes IX and X in 2019-20 compared to just one in nine among ‘general’ category students. In Assam, over a third of all students dropped out at this stage, reveals data from the recently released Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE). Assam and Bihar were the only two states where more girls than boys dropped out at this level.

Class IX and X saw the highest proportion of students dropping out. At the primary level, the proportion that dropped out was very small, mostly below 5%, except among tribal students. At the upper primary level too, the proportion dropping out was less than 2% in most states barring a few like Bihar (9%), Jharkhand (8%) and Gujarat (5%) and among tribal and Dalit students.

States with the highest proportion of students dropping out in class IX and X were Assam (34.4%), MP (26.8%), Gujarat (24.1%) and Odisha (24%) in that order. Interestingly, Delhi had a higher proportion dropping out in classes IX and X (21.5%) than the all-India proportion (16.1%), and marginally higher than even Bihar or Chhattisgarh.

Two states with significant tribal populations, Odisha and MP, had the highest proportion of tribal students dropping out at the secondary level — 31.5% and 30.9% respectively. Gujarat and Maharashtra, which also have sizeable tribal populations, too had over 26% tribal students dropping out at class IX and X level.

Assam had the highest proportion of students dropping out at the secondary level but the dropout rate among tribal students was lower than in all other categories. This seems to be true in other northeastern states like Nagaland, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh. Punjab, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh had the lowest proportion of students dropping out at the secondary level. But one in five tribal students in Kerala and a third of them in Tamil Nadu dropped out at the secondary level, showing the school system’s inability to retain tribal students compared to those from other categories.

Among the larger states, Assam, Odisha and MP, followed by Jharkhand and Bihar in that order had the highest proportion of scheduled caste students dropping out at the secondary level. Odisha had the most stark difference between general category students and the rest. There was zero dropout at the secondary level in the general category, while it was almost a third for every other category. The gap was similarly huge in Jharkhand too.

In Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the dropout rate was higher for general category students at the secondary level than for other categories.

Electricity connections

2017

Over 37% of schools in India have no electricity, August 4, 2017: The Times of India

Govt: All Delhi Schools Have Power Supply

In an indicator of the state of infrastructure in the country's institutions, the Centre told the Rajya Sabha on Thursday that over 37% of schools did not have electricity connections till March 2017.

Only 62.81% schools in the country have electricity connections, the government's report said. Jharkhand is at the bottom of the list, with just 19% of schools in the state having access to electricity . The national capital, along with Chandigarh, Dadar and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep and Puducherry top the list with all schools having electricity connection. Some of the states with poor access to electricity are Assam (25%) and Meghalaya (28.54%).

Others in the list include Bihar (37.78%), Madhya Pradesh (28.80%), Manipur (39.27%), Odisha (33.03%) and Tripura (29.77%).

State minister for HRD Upendra Kushwaha, in written response to a question at the Rajya Sabha, stated that the National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA) annually collects the information on various educational indicators, including infrastructural facilities in schools through the Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE).

Kushwaha said that the Centre supported state governments and Union Territory administrations for creation and augmentation of infrastructure facilities, including electrification in government elementary and secondary schools under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan programmes.

Under Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, 1,87,248 elementary schools have been provided internal electrification up to 2016-17 and under RMSA, electricity have been provided in 12,930 secondary schools so far.

Elementary schools

2016: shortage of teachers

Saroj Kumar , Primary education “India Today” 11/12/2017

From: India Today

See graphic

Lack of elementary school teachers

Enrolment

2000-2018: major gains

Manash Gohain, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

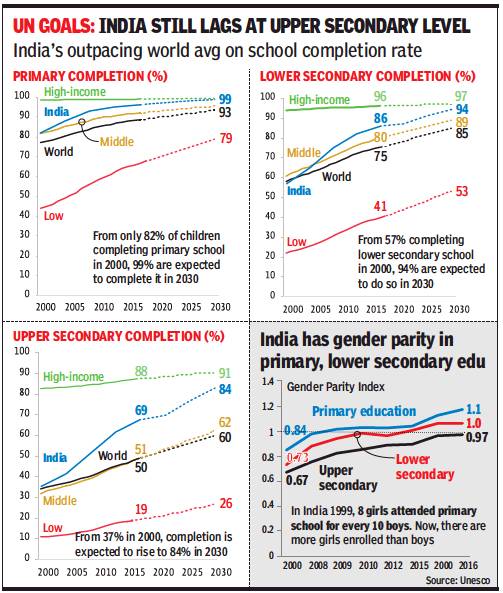

Gender parity in Indian schools.

From: Manash Gohain, July 13, 2019: The Times of India

India, defying the global trend, is likely to meet the 2030 deadline to reach the 100% child enrolment and school completion target set in the Sustainable Development Goals of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco). The new projection prepared for the UN High-level Political Forum stated that “the world will fail its education commitments without a rapid acceleration of progress” and by 2030 one in six aged 6-17 will still be excluded. However, for India, 99% of children are expected to complete primary school in 2030 and 84% projected to complete upper secondary school.

The India data, sourced exclusively by TOI, also revealed improvement in gender parity — since 2008 and 2012, there have been more girls enrolled in primary and lower secondary, respectively.

The projection highlighted that many children still drop out and by 2030, 40% will still not complete secondary education at current rates. While the global education goal, SDG 4, calls on countries to ensure children are not only going to school but also learning, the proportion of trained teachers in regions like sub-Saharan Africa has been falling since 2000. At current trends, by 2030, learning rates are expected to stagnate in middleincome countries and Latin America. Without rapid acceleration, globally, 20% of young people and 30% of adults will still be unable to read by the deadline.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development emphasises leaving no one behind yet only 4% of the poorest 20% complete upper secondary school in the poorest countries, compared to 36% in the richest. The gap is even wider in lower-middle-income countries.

However, for India the future looks promising with 99% expected to complete the primary school in 2030. From only 37% completing upper secondary education in 2000, 84% are expected to complete in 2030. In comparison, onefourth of all children are not explected to complete primary school in Pakistan and one in 10 in sub-Saharan Africa.

In terms of gender parity in school, in 2006, only 53% of Indian girls were completing lower secondary education, compared to 66% of boys. Now, the rates are fairly similar — at 79% and 82%. In 1999, just over eight girls attended primary school for every 10 boys. By 2012, enrollment numbers were even. Now, there are more girls enrolled than boys.

While globally, in terms of sex, 70 young women in low-income and 88 in lower-middle income countries complete upper secondary school for every 100 young men who do so. Gender disparities reverse in richer countries — 106 young women in upper-middle and 107 in highincome countries complete upper secondary school for every 100 young men.

In a complementary publication of the projection, it highlighted “In India, a programme in Bihar provided a bicycle to every girl entering grade 9 or 10 to reduce their dropout rates, and the national Mahila Shakti Kendra initiative supported village-level Women Empowerment Centres offering development of skills such as digital literacy.”

Manos Antoninis, director of the Global Education Monitoring Report, Unesco, said: “Countries have interpreted the meaning of the targets very differently. This seems correct given that countries set off from such different starting points. But they must not deviate too much from the promises made in 2015.”

The Global Education Monitoring Report calculated in 2015 that there was a $39 billion annual finance gap to achieve the global education goal and yet aid to education has stagnated since 2010.

“The onus shouldn’t all be on donors to fix the problem,” said Silvia Montoya, director of the Unesco Institute for Statistics. “Countries need to face up to their commitments too.”

Fees

Govt can regulate fee hike by pvt schools: HC

The Times of India, Jan 20 2016

Abhinav Garg

HC: Can't Engage In Profiteering Of Education

Govt can regulate fee hike by pvt schools

In a landmark verdict, the Delhi high court put an end to what it called “profiteering and commercialisation of education“ and empowered the state government to regulate fee hike by private schools. A day after it asked the AAP government to “set its house in order“ and improve its schools, the court ruled that fee hike by private unaided schools, who got DDA land at concessional rates, requires prior sanction from the Delhi government's education department. The order is expected to curb arbitrary fee hike.

“It is clear that schools cannot indulge in profiteering and commercialisation of school education... Quantum of fees to be charged by unaided schools is subject to regulation by DoE under Delhi Schools Education Act and it is competent to interfere if hike in fee by a particular school is found to be excessive and perceived as indulging in profiteering,“ a bench of Chief Justice G Rohini and Justice Jayant Nath held.

The court further ordered DoE to ensure compliance. It also directed DDA to take action against those private schools which violate the embargo on fee hike in the letter of allotment of land.

The judgement came on a PIL filed by advocate Khagesh Jha for an NGO, Justice For All, which urged the court to intervene and ensure that recognised private unaided schools situated on land allotted by DDA adhere to specified norms and take prior sanction of DoE before hiking their fees.

Action Committee for Unaided Recognised Private Schools, an umbrella body of school associations in Delhi, has decided to “immediately move the Supreme Court“ against the HC verdict.

“This is contrary to the earlier judgment of the Supreme Court in the TMA Pai case in which complete autonomy was granted to private schools with regard to fee structure.This cannot bypass the SC judgment. We have no alternative but to immediately move the matter to the SC,“ said SK Bhattacharya, president, Action Committee.

RC Jain of Delhi State Public School Management Association pointed out that school fees are decided by school management committees, which include nominees of DoE.

Sanskriti admission deadline extended

The Delhi government's deadline of January 22 for nursery admission forms was on Tuesday extended till this month end for Sanskriti School by the Supreme Court. It also decided to set up a three-judge bench to hear the matter.

The Centre and the school administration have assailed in the apex court the decision of the Delhi high court setting aside the 60% quota in the school for the children of group-A government officials who are in the highest class of government servants.

They have also sought an interim order allowing the institution to continue with the admission process under the old scheme till the matter is finally decided by the court.

‘Govts shouldn't mess with private school fees’

GURCHARAN DAS, Why govts shouldn't mess with private school fees, August 6, 2017: The Times of India

Imagine you are a young, idealistic person and you start a private school. You hire inspired teachers like yourself. The school does well and gets a nice a new law, the Right to Education reputation. Then a new law, the Right to Education Act (RTE) comes in 2010. It mandates parity with teacher salaries in government schools. You are forced to triple your teachers' salaries to Rs 25,000 per month. Even Doon School has to raise its salaries. The law also insists that 25% of your students must come from poor families. Although the government is expected to cover fees of the poor, it pays only a partial amount or none at all.Fees of the 75% students rise steeply to cover the costs of both factors. Soon, teacher salaries rise again to Rs 35,000 as mandated by the pay commission. Again, you have to raise fees.

Parents are angry now with constantly rising fees and `fee control' becomes a political issue. The government steps in with a new law to control student fees. Gujarat, for example, caps the fee at Rs 1,250 per month for primary and Rs 2,300 for high schools. Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Punjab also have fee caps and Uttar Pradesh and Delhi are considering one. Your school's survival is threatened because fees will not cover your costs. You have three choices. You can either bribe the school inspector, who is happy to show you how to fudge your accounts; or you can severely cut back on the quality of your school programmes; or you close down. Ironically , you had supported the RTE law, which raised teacher salaries and gave the poor a chance for a good education. Since you are an honest person and won't compromise on quality , you are forced to close down your school.

Parents are devastated. The widespread clamour for fee control results in the closure of good schools. As a parent, your choice now is to send your child to a government school or an inferior private school. Most parents won't opt for a government school -although it offers free tuition, textbooks, uniforms, school bags, meals -because teachers are frequently absent or are not teaching. This is why even children of the poor have been abandoning government schools. Between 2011-15, enrolment in government schools fell by 1.1 crore and rose in private schools by 1.6 crore, as per government's DISE (District Information System for Education) data.

Capping fees is a form of price control, which used to be a ubiquitous feature of our socialist days under Nehru and Indira Gandhi. It only created huge shortages and a black economy . The Soviet Union also collapsed partly because of price controls. But we have come a long way since then. Hence, it is curious that this damaging idea has become a political issue. Only 18% of private schools charge fees higher than Rs 1,000 per month and 3.6% charge more than Rs 2,500 a month. So, where are the votes? Narendra Modi knows this and has privately expressed his reservations against fee caps. He realises that there is vigorous competition between private schools, especially in cities, and this has kept private schools fees low -the national median fee today is only Rs 417 per month. You don't need fee control because competition keeps the prices low. Moreover, state governments spend two to three times per child in state schools than the fee cap.

What then is the answer? It lies in the SelfFinanced Independent Schools Act 2017 of Andhra Pradesh, which encourages private schools to open, gives them freedom of admission and fees, and removes corruption from board affiliation. To the Andhra model, we should add a requirement for extensive disclosure on each school's website -giving all fees, staff qualifications, details of infrastructure, strengths and weaknesses -everything that a parent wants to know before selecting a school. With competition, fee control becomes unnecessary .

Private schools have played a vital role in keeping India afloat in the past seventy years. Their alumni have filled the top ranks of professions, civil services and business. Their leadership has made India a world class software power. The government should focus on improving government schools rather than messing with the fees of private schools. As citizens, we should drop this sinister demand for fee control. Instead, let us sing along with Nat King Cole, who expresses nicely our attitude to private schools: `Sometimes I love you, sometimes I hate you. But when I hate you, it's because I love you'.

Fee hike: Govt. approval needed—SC

Unaided pvt schools need Upholds govt nod for fee hike: SC, Jan 24, 2017: The Times of India

Private unaided schools that were granted subsidised land by the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) in the national capital would not be able to hike fees without approval from the government, the Supreme Court said.

A bench of Chief Justice J S Khehar and Justices N V Ramana and D Y Chandrachud refused to interfere with the order of the Delhi high court which had in January last year held that the schools were bound to seek approval from the directora te of education (DoE) before increasing fees.

The high court had held that schools granted land at cheaper rates by DDA could not indulge in profiteering and commercialisation of education by increasing fees on their own and directed that approval from the directorate of education was a must before taking such a decision. “Quantum of fees to be charged by unaided schools is subject to regulation by DoE... under the Delhi School Education Act, 1973, and it is competent to interfere if the fee hike by a school is found to be excessive and perceived as indulging in profiteering,“ the court had said. The HC had passed the order on a petition filed by an NGO, Justice for All, which contended there were close to 400 private-unaided schools which had been allotted government land in the city. The list includes Modern School (Barakhambha), DPS (RK Puram), Air Force Bal Bharti School (Lodhi Road), Amity International School (Saket), Sanskriti School (Chanakyapuri), Mirambika Free Progress School (Sri Aurobindo Ashram), Convent of Jesus and Mary (Bangla Sahib Marg), Ryan International School (Mayur Vihar) and Ahlcon International School (Patparganj).

The fees of high end schools

2017

See graphic:

The fees of high end schools in India in 2017

Government (central) guidelines

Weight of school bags, homework for Class I, II

From: Manash Gohain, Centre fixes weight of school bags based on class, November 27, 2018: The Times of India

No Homework For Students In Class I & II

Children’s school bags are set to get lighter as several states and Union territories are acting on a recent communication from the Centre to formulate guidelines that set out the maximum weight in accordance to the class in which students are enrolled.

The HRD ministry, which had announced “rationalisation” of school syllabi by culling irrelevant or obsolete content, has said Class X school bags must not exceed 5kg while for Classes I and II, they should not be more than 1.5kg. The norm for Classes III to V would be between 2kg and 3kg, for VI and VII it should be 4kg, and for Classes VIII and IX 4.5kg.

The Centre’s letter to states, UTs and education boards also states that there will be no “homework” for Classes I and II and no subject other than language and mathematics will be prescribed for these classes. For Classes III to V, schools will teach only environmental science (EVS), mathematics and languages as prescribed by NCERT.

Government proposal

‘Ensure students don’t bring additional books to school’ '

The letter sent to the states asks them to “formulate guidelines to regulate the teaching of subjects and of schoolbags in accordance with government of India instructions”. Following the communication, some states issued circulars to education departments to comply with the directions with immediate effect. Some like Delhi said they have not yet received the MHRD’s letter, which was issued last month.

The Centre’s move is in keeping with the MHRD’s initiatives to reduce schoolbag weight and also rationalise teaching calendars to ensure more time for nonacademic activities like sports and other skills.

While setting class-wise weight limit on schoolbags, the Centre has asked states and UTs and education boards to ensure “students should not be asked to bring additional books, extra materials”. While Lakshadweep administration has implemented the guidelines with immediate effect, some other states like Karnataka will issue their norms based on the MHRD’s direction.

The ill-effects of heavy schoolbags may not be immediately evident but physicians say they can have an adverse impact on the nervous system besides being a physical burden for kids. Dr Ramneek Mahajan, director, orthopaedics and joint replacement, Max Smart Super Speciality Hospital, Delhi, said heavy schoolbags can cause lasting damage like spinal deformities as children’s skeletal frames are not fully formed.

“The excess weight puts undue stress on the muscles, ligaments and discs and damages them. Children develop a forward head posture as they are swinging forward at the hip to compensate for the heavy weight. In the long term, they are developing imbalances that can affect the nervous system,” he said.

Homework

Prevalence: as in 2017?

Despite efforts by the government and schools to lessen the burden of homework, 74.3% of Indian teachers still use home assignments as a top tool to assess students, says a National Achievement Survey report for Classes 3, 5, and 8.

Only 24.3% of teachers depend on project-based or experiential learning to assess students, the survey found. Rajasthan (93%), Himachal Pradesh (92%), Haryana (92%) and Uttarakhand (91%) led the list of states where teachers almost entirely assess students on homework.

In Karnataka, 83% of teachers used home assignment as a tool to assess students’ abilities while 39% gave importance to project work. Tamil Nadu (67%), Puducherry (53%), Andhra Pradesh (45%), Odisha (40%) and Tripura (42%) attached more importance to project work, says the survey.

“This is because there is no proper plan,” said Nirajan Aaradhya VP, fellow at Centre for Child and Law at the National Law School of India University. He said for project work, a 30-minute period is too short. “ We can’t blame it on teachers. A period of about 45 minutes is enough to make learning fun and interactive,” he added.

Laboratories

2013: 75% of schools lack decent labs

75% of schools lack decent science labs

Subodh.Varma@timesgroup.com

The Times of India Aug 19 2014

More than three quarters of schools in the country do not have fully equipped science laboratories for students in class 11 and 12, a survey of 2.4 lakh secondary and senior secondary schools has found. For classes 9 and 10, where an integrated science module is taught to students, over 58% schools don't have the requisite lab.

“This is an atrocious state of affairs,“ says a sad Professor Yashpal, scientist and former chairman of the UGC who has been one of India's most well-known science communicators. “Everybody knows the importance of labs in science teaching. But learning science has been reduced to mugging up things,“ he said.

The shocking state of science teaching at school level contrasts with the high profile science education and research institutions at the top like IITs, IISc and others. The survey was carried out under the Unified District Information System on Education and data analysed by Delhibased National University for Educational Administration and Planning. The report was released recently .

In several states the situation is much worse than what the national average indicates. In Karnataka, just 6% of schools have fully equipped labs for senior students while in Andhra, the share is a mere 13%. Kerala and Tamil Nadu have a better share -34% and 38%, respectively. In Assam, just 4% schools have labs while in Bengal the share of such schools is only 6%. In smaller states and union territories like Delhi, Puducherry, Chandigarh, Goa and even Manipur, the situation is relatively better.

Perhaps this dire situation is there because there are no science students? Although this in itself would be a matter of serious worry , data in the same report shows that over 5.4 million students study science. That's more than one-third of students covered in the survey . Note that these students are spread over all schools.In fact, 43% of schools offer science to senior students, as stated in the report.

Medium (language) of instruction

As in 2018-19

Manash Gohain, September 11, 2020: The Times of India

From: Manash Gohain, September 11, 2020: The Times of India

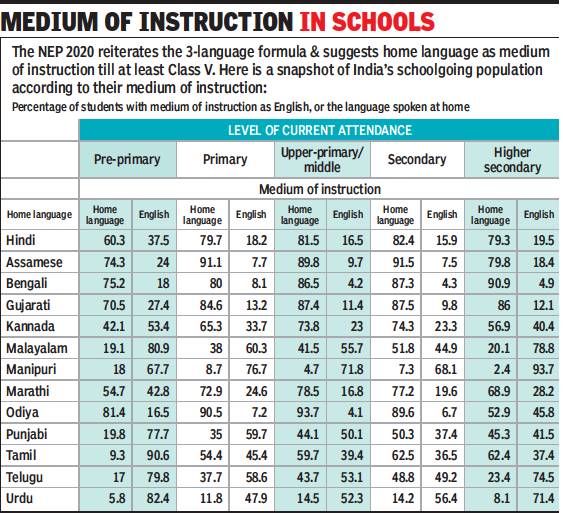

Amid a raging debate over “imposition of languages”, official data points to over 50% of students completing their secondary level of education with one of 12 Indian languages and senior secondary level with one of eight home languages, other than English, as the medium of instruction.

According to National Statistical Organisation’s (NSO) latest report on education, 70% or more students whose home language is Assamese, Bengali and Gujarati completed their school education in these vernacular languages. However, more students whose mother tongue is Malayalam, Telugu, Manipuri, Punjabi, Urdu, Sindhi, Konkani or Nepali opted for English as the medium at least till Class X.

In general, a significant shift towards English medium is seen at senior secondary level — Classes XI and XII.

The National Education Policy 2020 reiterates the three-language formula and suggests medium of instruction in home language at least till Class V. The RTE Act also suggests that the mother tongue should be considered as the medium of instruction wherever possible.

The NSO survey reveals that 91.1% of students whose mother tongue is Assamese are learning in their home language at the primary level, the highest for any mother tongue at this level, followed by Odiya at 90.5%. At upper-primary or middle school level, 93.7% of the students whose mother tongue is Odiya are learning in their home language, followed by Assamese (89.8%), Bengali (86.5%) and Hindi (81.5%).

On the other side of the spectrum are Sanskrit, Urdu, Manipuri, Bodo, Konkani, Nepali and Sindhi, where the percentage of students studying in their home language is significantly low. As per the survey, there are no students attending classes in Sanskrit medium. In the primary and middle-school level, just 8.7% and 4.7% of students have opted for Manipuri medium, while it is 11.4% and 28.6% for Nepali. The figures for Urdu as home language and medium of instruction are 11.8% (primary), 14.5% (middle-school) and 14.2% at secondary level.

The survey also showed that preference for English as a medium of instruction is more prevalent at the starting phase of schooling and at senior secondary level.

Policies, reforms

No-detention policy fails

The Times of India, Jun 19 2016

For those who grew up in In dia jumping hoop after hoop from kindergarten to Class XII, school seems unimaginable without the fearsome final exam which determined whether you went ahead or not. Now, a few years after the Right to Education (RTE) Act ended the passfail system until Class VIII, many states say that students are failing in large numbers and learning levels have plummeted. In Delhi, for instance, the proportion of students repeating Class IX rose from 2.8% in 2010 to 13.4% in 2014.

By eliminating the final exam, “the last modicum of accountability in government schools has been taken away ,“ says Atishi Marlena, adviser to Delhi education minister Manish Sisodia. Students can coast from class to class without being able to achieve basic levels of reading, writing and comprehension, say those who oppose no-detention.

Now, policymakers seem to think that the no-detention policy of the RTE Act is failing students, weakening teachers and misguiding parents. “We heard out people from across the spectrum, and all the secretaries were unanimous in their view that the child and the teacher both lose out,“ says former civil servant Shailaja Chandra, a member of the TSR Subramanian committee set up by the HRD ministry to examine an education overhaul. The committee has recommended scrapping the no-detention policy after Class V.

In 2012, a Central Advisory Board of Education sub-committee, headed by Geeta Bhukkal, then education minister of Haryana, had said that the policy might work if schools had greater resources and all-round motivation, but that for now, no-detention was difficult to implement.

The no-detention policy , though, is not the woolly-headed and kind-hearted intervention it is now being made out to be. No detention emphatically does not mean the end of regular testing.It is meant to go along with a system of continuing and comprehensive evaluation (CCE), which lets a teacher evaluate a child's learning levels, and regroup those who need remedial help in certain subjects.

Exams, after all, are not elim ination exercises meant to demoralise a child they are meant to gauge and improve learning.“No other place, the US, Europe or any other place that India aspires to be, wastes public money by making a child waste a year because she needs help in a certain area,“ says Krishna Kumar, educationist and one of the architects of the RTE Act.

The colonial idea of a strictly controlled classroom, and a final exam that passes or fails a student, may be considered obsolete around the world but it still shapes the common Indian view of schooling. But while many believe that failure is a goad to learning, there is zero empirical evidence that detention improves academic performance. It does, however, extract psychological costs from a student. Even the Bhukkal committee found that the pass percentage in the Class X exams improved after the system, and dropouts, especially among children from disadvantaged backgrounds, had considerably decreased. The Subramanian committee report also admits that the no-detention policy has been “empirically validated“, keeping children in school for those eight years and also raising pass percentages across boards.

“The problem is not the policy , it is the way it has been communicated,“ says Vimala Ramachandran, former NUEPA professor. “In our surveys, we found it had become a licence not to do any assessment at all. Teachers mechanically filled out forms as though it was another administrative task, without doing the activities required to evaluate the child's capabilities,“ she says. While upper-end private schools can easily incorporate this, many government schools are challenged, she says. Both teachers and administrators are bewildered by these new demands, and the system tends towards laxity , rather than creativity . “In large classrooms, where the teachers are themselves preoccupied, it has been difficult for them to pursue the child's development, or for there to be outside monitoring of each child's progress,“ says Chandra.

But scrapping no-detention is the equivalent of wilfully breaking the RTE-conceived schooling system, and then declaring it broken, say others. “The no-detention policy cannot be seen in isolation, but in the context of the neglect of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and RTE goals,“ says Kumar.

Playgrounds

Schools with playgrounds

See graphic 'Schools with playgrounds'

STATOISTICS - State of Play

The Times of India Jul 29 2014]

The fact that today's urban children have little playing space where they live is well known. That makes adequate playgrounds in schools even more important. This is not just to improve India's performance in sports, but because studies have shown that school-level games play an important role in a child's personality development by teaching them to cooperate, plan, negotiate and so on. But data analysed by TOI shows that there are many states, including Bihar and Orissa, where seven out of ten primary schools don't have playgrounds. Data from the Unified District Information System on Education (U-DISE) suggests that access to playgrounds improves somewhat in secondary schools.

Private Schools

1978> 2017

From: Manash Gohain, Pvt schools grooming about 50% of students in country, July 23, 2020: The Times of India

Now World’s Third Largest School System

New Delhi:

Nearly 50% (12 crore) students in India today are enrolled in private schools, making it the third largest system in the world behind China’s education system and India’s public school system. While the growth of enrolment in government schools dropped from a little over 74% in 1978 to 52% in 2017, in private schools it grew from just above 3% to nearly 35% in the same period. Even as it contributes nearly Rs 2 lakh crore to the economy, the private school growth story is also inhibited by low learning levels, lack of transparency and regulatory issues.

“The State of the Sector Report: Private Schools in India”, a comprehensive study by Central Square Foundation based on government data calls for transparency from private schools to improve their quality and for the government to play a role in regulating their fees. Contrary to the perception of being elite, the report highlighted that 45% of students in private schools pay less than Rs 500 a month as fees and 70% pay less than Rs 1,000 a month as fees. According to the report, enrolment grew by nine percentage points between 1998 and 2007, and ever more rapidly, by 16.6 percentage points, in the next decade between 2007 and 2017.

However, the issue of low learning outcomes plague private schools as well with 60% of rural private school students in class V unable to do a three-digit division, 35% failing to read a basic class II level paragraph, and average score for class X students in private schools dipping below 50% in four out of five subjects.

Releasing the report, Amitabh Kant, CEO, Niti Aayog said: “There is an information asymmetry that exists. Though enrolment has increased exponentially in private schools, the learning outcomes have stagnated for a decade now. They have to really focus on learning outcomes as that is critical. Various state governments also need to rethink on a regulatory framework for private schools and focus on learning outcomes rather than on any other inputs.”

As per the report, factors driving low learning levels are lack of information around school quality with the only independent markers being the board examinations. And with 60% of the private unaided schools ending before the grade board exam testing, it becomes difficult for parents to judge the quality of their schooling options. Also a far greater number (42%) of private unaided schools offer English as a language of instruction as opposed to 10% of government schools. But, schools which are English medium on paper may not be so in practice.

Private schools, unaided

Terminating services of teachers

The Times of India, April 17, 2016

A driver who was sacked by a private school in 2003 has secured a judgment from the Supreme Court forbidding recognised schools in Delhi from dismissing any employee, including teachers, without "prior approval" of the director of education.

In its judgment on April 13, SC upheld a provision in the Delhi School Education Act 1973 that requires all recognised schools to obtain the government's approval before sacking an employee. The section — 8(2) of the DSEA 1973 — had been struck down by the Delhi high court in July 2005. Terming the 2005 decision "bad in law", the apex court observed, "The intent of the legislature while enacting the same (Section 8(2)) was to provide security of tenure to employees of schools and to regulate the terms and conditions of their employment." Activists said the judgment will check "victimisation" of teachers who dare to raise their voice against arbitrary and illegal decisions of private school managements.

The SC ruling is a shot in the arm for teachers such as Asha Rani, Payal Singh (name changed on request), Dinesh Chand Sharma and their colleagues. According to Asha Rani, 43, she was suspended from a school in Sector 15, Rohini, and two of her colleagues were fired for demanding full salary and benefits.

"Our salaries were being transferred to our accounts but the management took signed, blank cheques from us and withdrew the money. Our actual salaries were being paid in cash," alleges Asha Rani. About 60 teachers had filed a cheating case in 2010. Now, most have inquiries against them. "Other Rohini schools sacked teachers too or they quit under pressure. With this judgment, schools will have to first take permission from the government."

Right to Education (RTE)

Per-child expenditure by states/ 2019

From: January 11, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Per-child expenditure by states on Right to Education (RTE), 2018

Under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, if the Center's reimbursement of per-child expenditure by states is an indication, the Hindi heartland (excluding the national capital) has a long way to go.

School bags

2020: weight not to exceed 10% of child’s weight

Manash Gohain, December 9, 2020: The Times of India

School bags should not be more than 10% of the body weight of students across classes I to X and there should be no homework till class II. The new ‘Policy on School Bag 2020’ of the Union ministry of education also recommends that the weight of the bag needs to be monitored on a regular basis in schools. They should be light-weight with two padded and adjustable straps that can squarely fit on both shoulders and no wheeled carriers should be allowed. The policy even recommends that the weight of each textbook may come printed on them by the publishers.

The recommendations have been arrived based on various surveys and studies conducted by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). The policy stated that data collected from 3,624 students and 2,992 parents from 352 schools, which include Kendriya Vidyalayas and state government schools were analysed.

The ‘Policy on School Bag 2020’ made 11 recommendations on the weight of the bags, including adequate good quality mid-day meal and potable water to all the students so that they need not carry lunch boxes or water bottles.

The policy also recommended that children with special needs be provided a double set of textbooks, through book banks in schools and lockers in classes for storing and retrieving books and other items.

The policy said there should be no bags in pre-primary. For classes I and II the bag weight range should be between 1.6 kg to 2.2 kg. Like-wise it should be 1.7 kg to 2.5 kg, 2 kg to 3 kg, 2.5 to 4 kg, 2.5 kg to 4.5 kg and 3.5 kg to 5 kg for classes III to V, classes VI and VII, class VIII, classes IX and X and classes XI and XII respectively.

Recommending that total study time should be accounted for while planning the syllabus, the policy said while there should be no homework upto class II and a maximum of two hours per week for classes III to V, homework duration for classes VI to VIII should not exceed one hour a day and two hours a day for classes IX and above.

The standard of school education in India

2016-17

From: Oct 11, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Statewise scores on education indicators, 2016-17

2017: National Achievement Survey

Learning levels

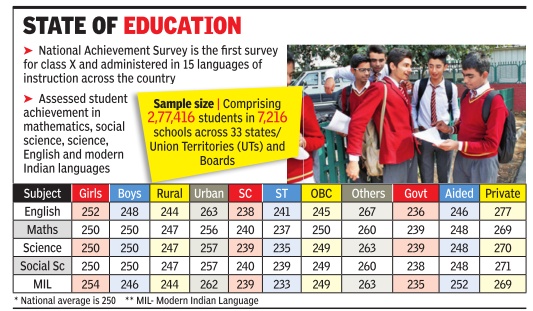

Manash Gohain And Atul Thakur , February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Students are learning less as they move to higher classes, a survey of over 1 lakh students in government schools in over 700 districts shows. On average, a class VIII student could barely answer 40% of the questions in maths, science and social studies. The national average score for language was a little better at about 56%.

The findings raise doubts about the demographic dividend India hopes to reap because of a young population. Educationists, experts and rights’ activists are not surprised. They say this is a result of insufficient investment in public education and the government’s inability to implement the Right to Education Act (RTE) in letter and spirit.

The district-wise National Achievement Survey 2017 by National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) tested students in all major subjects in classes III, V and VIII. It used multiple-choice test booklets in maths, language, environmental science, science and social studies. While NCERT is yet to release the national and state-wise data, TOI compiled the district-wise results released so far.

In class III, students averaged between 63% and 67% marks in environmental science, language and maths. In class V, average scores fell by about 10 percentage points to 53-58%, and in class VIII, the fall was even sharper, although language scores dipped only a little. No other subject was common between these classes.

Among regions, the south did better in the early years of schooling. For example, in class III, students in the south scored more than those in the north and the east, and were behind those in the west only in language. In class V, too, they had higher average scores than the rest, but in class VIII, students from the west outperformed all other zones. The south remained ahead of the north, but scored less than the east in science and social studies.

Rural students scored higher than those in cities. Also, in classes V and VIII, OBC students outscored the general category. At all levels, average scores were lowest for ST students while SC students scored a tad higher.

Educationists say such generic surveys are futile if the results are not used to improve teaching. Prof R Govinda, former vice-chancellor of National University of Educational Planning and Administration, said, “The results don’t surprise since basic skills are not being inculcated and cumulatively, the deficit will increase. The results for the last 10 years have been the same, which means we have not done anything. The question is, how can we utilise the study results to improve the teaching-learning process. How are we going to improve teaching in the classroom?”

Ambarish Rai, national convener of RTE Forum, said government has failed to provide adequate funds for school education and implementation of the RTE Act. “RTE is a package for school development. We cannot look at any part of it in isolation.” He said the RTE Act prescribes one teacher for every 30 students at the primary level, and for 35 students in higher classes, but these have not been implemented. The country is short of 10 lakh qualified teachers, he said.

Rai disagrees with those who say that the results are fallout of the no-detention policy, and the Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) process, both of which the Centre removed last year. “The no-detention policy has no role, as it was linked to CCE, which the government failed to implement. CCE is a scientific methodology to assess a child’s performance and explore the possibility of improvement. No detention helped reduce the dropout rate. No research or study in any country shows any relation between detention and learning levels.”

Rai said learning levels will improve when teachers are as per RTE norms. “The teacher training institutes are run by the private sector and government has no mechanism to train teachers. Improving government schools is only possible after complete implementation of RTE and the promised 6% GDP to education.”

Girls outshine boys, rural beats urban

February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Girls outshone boys

Rural stuents beat urban ones

Western India was the best region, and

OBC students did better than ‘general’ students.

From: February 24, 2018: The Times of India

One of the more surprising revelations of the district-wise National Achievement Survey 2017, is that rural students do better than their urban peers.

In class III, urban students outscore their rural counterparts in EVS but score lower in language and mathematics. At higher levels — both classes V and VIII — rural students score better in all subjects except language. Data shows the gap between rural and urban students keeps increasing in higher classes.

It may be because government schools in urban areas are so neglected that parents prefer to send their children to private schools, said Ambarish Rai, national convener, RTE Forum, an NGO. “With crowded classrooms, insufficient number of teachers, and students not getting books and uniforms on time, the government schools are in a pathetic condition.” Rai noted that the results are much better wherever the government invests in its schools. “Kendriya Vidyalayas, where the allocation is eight times higher than in other government schools, are performing better than their private counterparts.”

Girls outperform boys at all levels, but the gap narrows with age. This is probably because in both rural and urban set-ups, girls are additionally burdened with household chores such as helping in the kitchen and taking care of younger siblings.

“Social challenges for girls increase as they grow. This is a major reason why there is also an increase in the dropout rate of girls in higher classes. The Beti Bachao Beti Padhao scheme cannot run on a Rs 200-crore allocation,” Rai added. Girls, however, appear to have a definite advantage over boys in understanding of language. At all levels, the difference in average scores of boys and girls is the highest in language.

7/ 9 worst districts are in UP

Why scoring even 30% is so tough in seven UP districts, February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Of the 700-odd districts in the country, nine have such low standards of school education that students struggle to score 30% marks, and seven of these districts are located in the most populous state, Uttar Pradesh.

The ‘best districts’ in terms of learning outcomes are those where the average score is 80% in class III, 75% in class V, and 70% in class VIII. These are spread across all states, but with a higher concentration in Rajasthan, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra.

The ‘worst’, though, are in UP — Shamli, Ghazipur, Kheri, Varanasi, Maharajganj, Mirzapur and Sambhal, and in Arunachal Pradesh (Changlang) and J&K (Pulwama).

Students here couldn’t score over 30% in at least five of the 10 tests in the NAS (three each for classes III and V, and four for class VIII).

Educationist Ashok Ganguly said UP’s poor showing is mainly due to the prolonged shortage of teachers and lack of activity-based learning in government schools. “There are more than 50,000 schools under the government with a huge shortage of teachers, especially in science and mathematics,” he said. Ganguly was also chairman of Central Board of Secondary Education and director SCERT in UP. “UP students shy away from taking mathematics and science class IX onwards as they have not been taught properly in the lower classes. Wherever we have science teachers, there is no hands-on activity as there are no laboratories. How can you comprehend subjects like science without learning by doing?” he added.

Terming this a systemic failure, Anita Rampal, professor and former dean at the faculty of education, Delhi University, said, “The system thinks anyone can teach. PT teachers are teaching mathematics. In Rajasthan, we have seen how girls have protested to demand teachers for their schools. We need dedicated teachers for subjects from class VI onwards and we need good teachers at the primary level.”

OBCs shine in govt schools

OBCs shine in govt schools, ST students bring up rear, February 24, 2018: The Times of India

The NAS 2017 data shows OBC students — not the general category — perform the best in government and government-aided schools. At the all-India level, OBC students outscored the general category in classes V and VIII, while being slightly behind in class III. SCs were behind both while STs had the lowest average scores.

Significantly, while the gaps are narrow to begin with and narrow further by class VIII, in language the gap widens between social groups as students move to higher classes.

The western region has a different pattern, though. SC students are the best performers in class III, followed by OBC, general and ST students, in that order.

In class V, the gap between the average scores of SC and OBC students gets narrower. In class VIII, OBC students are the highest scorers, followed by SC, ST and general students, respectively.

South is the only region where general students outperform everyone else through all levels and by larger margins in higher classes. Here, too, language remains the subject in which general students have the biggest edge.

In the eastern and northern regions general students score highest in classes III and V, but are overtaken by OBC students in class VIII.

Experts, however, warn against reading too much into these numbers. “Government schools have become the schools of OBC, dalits and minorities. They have fewer students from the general category, whereas schools should have been a place of socialisation of children,” said Ambarish Rai, national convener, RTE Forum.

“OBC and other marginalised children belong mostly to labour class and have different talents. But they don’t have equal opportunity to grow through quality learning. It is the state’s duty to provide them equal opportunity. That is why education was made a fundamental right,” added Rai.

Maths, language skills worsen from class III to class VIII

February 24, 2018: The Times of India

Across the 36 states and UTs, students’ performance in maths and language worsens as they move up from class III to class VIII. Maths is the biggest hurdle of all.

In class III, six states and UTs had average maths scores above 70%; another 17 averaged above 60%, while the remaining 13 scored 40-60%.

In class V, no state had an average score above 70% and just six averaged 60-70%, while Arunachal Pradesh alone finished below 40%. By class VIII, no state or UT averaged even 60% in maths, and 23 averaged below 40%. The minimum drop from class III was 13 percentage points, while in Nagaland, Puducherry, West Bengal and Telangana, the average maths scores fell by more than 30 percentage points.

Language shows a similar pattern. Average scores in class III were above 70% in 12 states and UTs, and between 60% and 70% in another 16. In class V, only Karnataka had an average of over 70% while nine states or UTs averaged between 60% and 70%.

By class VIII, no state averaged 70% or more, and just seven could average over 60%. In Nagaland, Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana and Mizoram, average language scores fell by over 20 percentage points between classes III and VIII.

However, experts questioned the nature of the survey. “This is purely a text-based writing assessment. Sometimes the questions are not comprehensible for students. No other methods were applied to understand their observation and lots of other things children would be doing while learning,” said Anita Rampal, professor and former dean at the faculty of education, Delhi University, who has written several chapters of NCERT’s elementary school textbooks.

“This is such a limited test. We have to first look at the nature of the question, which itself is a challenge,” she said, adding that “children understand things differently. Perhaps they are not familiar with the questions we give them.”

Terming it a ‘limited’ test, educationists said children understand things differently and were perhaps not familiar with the questions set for them

Poor infrastructure

Manash Gohain, Creaking school infra hitting kids’ learning, March 22, 2018: The Times of India

Poor school infrastructure has emerged as a key factor why children are “not learning” in government and government-aided schools across the country.

A state-wise analysis of the National Achievement Survey 2017 for classes III, V and VIII has highlighted that not only do school buildings need significant repair, the learning environment also doesn’t seem to be too conducive for teachers burdened by work overload, lack of drinking water and toilet facilities.

TOI had in one of the most comprehensive analysis of the NAS 2017 on February 24, 2018, highlighted how staff crunch, crowded classrooms and inadequate funds are to blame for poor learning outcomes in government schools as captured in the survey.

The state-wise analysis was finalised by NCERT and submitted to the ministry of human resource development recently, a copy of which is with TOI.

While across states, over 95% students like coming to school — a large number of students find the travel difficult. Lack of electricity at many schools is also one of the major factors highlighted by teachers in the survey.

2018: National Achievement Survey

From: Manash Pratim Gohain, Exams in classes V, VIII to return as no-detention policy ‘fails’ national test, May 28, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Government is considering passing requirements for Classes V and VIII from March 2019

NAS found that Class X students were performing worse than Classes III, V and VIII students

The National Achievement Survey (NAS) has delivered a sharp indictment of the ‘no-detention policy’ with learning outcomes deteriorating as students progress to higher classes, prompting the government to consider passing requirements for Classes V and VIII from March 2019. The fresh thinking follows the NAS revealing that Class X students of state boards were struggling to get even 40% of answers right in maths, social science, science and English, doing better only in Indian languages.

Conducted in all states and Union Territories with a sample of 15 lakh students, the NAS, which was carried out on February 5, 2018, found that Class X students were performing worse than Classes III, V and VIII students — evidence of the problem of poor learning being simply moved up the chain to higher classes. If 64% of Class III students of state, CBSE and ICSE boards answered a maths question right, the score was down to less than 40% for all state boards barring Andhra Pradesh for Class X. The NAS for junior classes saw the percentage dipping to 54% in Class V and 42% in Class VIII.

Outcomes for English reflected a similar declining graph. The average of students giving correct answers dipped from 67% in Class III to 58% in Class V and 56% in Class VIII to no state barring Manipur crossing 42% in Class X. “The no-detention policy has not worked. It was conceived in haste and poorly implemented. The government does not want to put students under more stress by compulsory grading in junior classes, but a passing requirement might be needed in Classes V and VIII,” awell-placed source said.

The problem, sources associated with the survey said, was one where the no-detention policy under Right to Education Act saw exams being devalued. “Teachers lost leverage over students and also interest in bothering about outcomes. Students lacked motivation to prepare for exams as there was neither reward nor failure attached to results,” said the source.

The result, as starkly brought out by the NAS, was a growing percentage of underperforming students as they moved to senior classes. The reintroduction of boards at Class Xis likely to deliver a shock in terms of poor pass percentages. Officials pointed to the high number of “failures” in Class XI in recent years as schools’ screen for the Class XII board exams, resulting in protests by students and parents.

Without meaningful evaluations, teachers and school managements are tempted to “kick the can down the road”, even as attempts to enforce exam discipline were met with resistance from students and parents. The no-detention policy, without adequate attention to ensuring learning outcomes, meant that exams were treated in a cavalier manner. It was only in modern Indian languages that state board students in as many as 19 states and UTs crossed the 50% correct-answer mark. This might indicate a higher proficiency in mother tongues. Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan came across as better performing state boards. Delhi had the highest overall score of 45.6%.

States: the best and the worst

2019-20

Swati Shinde Gole, June 7, 2021: The Times of India

From: Swati Shinde Gole, June 7, 2021: The Times of India

PUNE: From level IV to level III, Maharashtra has progressed in the performance grading index for 2019-20 academic year as against the previous year, riding on improvements in the governance processes and equality in education.

The state's progress in three other parameters such as learning outcome and quality, access to education and infrastructure remained unchanged when compared with 2018-19. The report was released by the Union ministry of education.

The assessment of the states was conducted based on five indicators - learning outcomes and quality, access, infrastructure and facilities, equity and governance processes.

The aim of the performance grading index was to pinpoint the gaps, and accordingly prioritize areas for intervention to ensure that the school education system is robust at every level. At the same time, it is expected to act as a good source of information for best practices followed by states and UTs which can be shared.

Former director of education, Vasant Kalpande, said, "Marginal changes in parameters in the sectors like health, achievements always happen when reviewed periodically. This is a natural phenomenon and such statistically insignificant differences don't need to have any specific reason or explanation."

The survey said the governance process parameters had many states score fewer points. This parameter was an important indicator as it would lead to critical structural reforms in areas ranging from monitoring the attendance of teachers to ensuring a transparent recruitment of teachers and principals.

Headmistress of a civic school in the city, Hema Mane, said, "It is common knowledge that shortage of teachers and principals and administrative staff, lack of regular supervision and inspection, inadequate training of the teachers, timely availability of finances are some of the factors plaguing the education system. Through the PGI, the shortfalls can be measured objectively and regularly. This is crucial for taking necessary steps to eliminate the gaps."

The survey report said in the case of learning outcomes, it has been observed that, in general, the scores obtained in the higher standards are less than those in the lower standards. It is therefore imperative to ensure better interventions at the lower standards as it will have a positive cascading effect at the higher levels.

Indicators like availability of ICT facilities and timely availability of textbooks and uniforms, which are critical inputs for better performance of students and mentioned in the RTE Act, are measured in the infrastructure & facilities domain. Significant shortfalls in these areas have also been captured by the infrastructure Index.

The status of school education in India

Rural schools: 2009-14

Jan 14 2015

Rural schools high on enrolment, but low on learning levels: Report

Akshaya Mukul

Pratham's 10th Annual Status of Education Report -the country's biggest private audit of elementary education in rural India -released Tuesday has a similar story as in previous years: rising enrolment, poor learning levels in reading, mathematics and English and growth in number of private schools. ASER also says improvement in school facilities -pupil teacher ratios, playgrounds, kitchen sheds, drinking water facilities, toilets -continues. HRD ministry is going to strongly dispute ASER's claims on falling learning outcomes since government's own report gives a different picture.

With Pratham gaining worldwide presence -from Pakistan to Africa -the ceremony , again like in the past, was a glittering event attended by industrialists, entrepreneurs and even chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian. Report for 2014 done after survey of 16,497 villages, 5.7 lakh children in over 3.4 lakh households across 577 districts says that for the sixth year in a row enrolment levels are 96% or higher for the age group of 6 to 14.

Rural schools, 2014-16

Pratham audit paints mixed pic of rural education, Jan 19, 2017: The Times of India

A private audit of school education in rural India paints a mixed picture of hits and misses increase in enrolment, no increase in private school enrolment, improvement in reading ability and arithmetic, but not so much in reading English.

After a gap of a year, Pratham's 11th Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) was unveiled on Wednesday in the presence of Delhi education minister Manish Sisodia and chief economic adviser Arvind Subramaniam. The survey was carried out in 17,473 villages, covering 3,50,232 households. Children's attendance shows no major change since 2014. Also, the proportion of small schools in the government primary school sector continues to grow.

The report that largely looks at enrolment pattern and learning abilities highlights that at the all India level, enrolment in the age group of 614 has marginally increased from 96.7% in 2014 to 96.9% in 2016. Similar increase can be noticed in the enrolment for the age-group of 15-16 from 83.4% in 2014 to 84.7% in 2016.

In states like Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and UP, the fraction of out-of-school children has increased between 2014 and 2016. In MP, it has been the highest from 3.4% to 4.4%. In three states, the proportion of out-of-school girls is higher than 8%. This includes Rajasthan (9.7%), UP (9.9%) and MP (8.5%).

There has been no increase in enrolment in private schools in the last two years.Enrolment is almost unchanged at 30.8% in 2014 to 30.5% in 2016. Gender gap in private schools has decreased slightly from 7.6 percentage points to 6.9 percentage points.

As for learning ability , na tionally the proportion of children in Class III who could read at least Class I text has gone up slightly from 40.2% in 2014 to 42.5% in 2016. Overall, reading levels in Class V are almost the same year on year from 2011 to 2016. However, the proportion of children in Class V who could read a Class II-level text improved by more than five percentage points from 2014 to 2016 in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tripura, Nagaland and Rajasthan.

However, in Class VIII, reading level has shown slight decline since 2014, from 74.1% to 73.1%. Except for Manipur, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, reading level does not show much improvement.

In 2014, nationally 25.4% of Class III children could do a two-digit subtraction which has risen slightly to 27.7% in 2016, mainly in government schools. However, in Class V , the arithmetic levels of children measured by their ability to do simple division remained almost the same at 26%.But among Class VIII students, the ability to do division has continued to drop, a trend that began in 2010.

Ability to read English has slightly improved in Class III but relatively unchanged in Class V . In 2016, 32% children in Class III could read simple words as compared to 28.5% in 2009. Worrisome is the gradual decline in upper primary. In 2009, 60.2% in Class VIII could read simple sentences in English; in 2014, this was 46.7% and in 2016, it has declined to 45.2%.

2017, 2018

From: Ishita Bhatia & Ardhra Nair, Why parents prefer these govt schools to pvt ones, January 23, 2019: The Times of India

From: Ishita Bhatia & Ardhra Nair, Why parents prefer these govt schools to pvt ones, January 23, 2019: The Times of India

In The Absence Of Adequate Infrastructure, Some Rural Schools Are Making The Most Of What They Have, And Getting Results

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) paints a grim picture of senior school students who can’t do basic math and juniors who don’t recognise alphabets. But there are schools that have set a blazing example despite all the odds — inadequate infrastructure, shortage of teachers, poor mid-day meals. Innovative, courageous and inspiring teachers have at times made such a difference that parents are shifting their wards from private schools into these nononsense classrooms.