Water: Drinking water, rural water and its availability, India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Water crisis in major cities

22 of India's 32 big cities face water crisis

Dipak Kumar Dash, TNN | Sep 9, 2013

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. (TOI photo by Balish Ahuja)

NEW DELHI: Water scarcity is fast becoming urban India's number one woe, with government's own data revealing that residents in 22 out of 32 major cities have to deal with daily shortages.

The worst-hit city is Jamshedpur, where the gap between demand and supply is a yawning 70%. The crisis is acute in Kanpur, Asansol, Dhanbad, Meerut, Faridabad, Visakhapatnam, Madurai and Hyderabad — where supply fails to meet almost 30% of the demand — according to data provided by states which was placed in the Lok Sabha during the recently-concluded Parliament session by the urban development ministry.

The figures reveal that in Greater Mumbai and Delhi — which have the highest water demand among all cities — the gap between demand and supply is comparatively less. The shortfall is 24% for Delhi and 17% for Mumbai. However, the situation is worse than that.

For example, in Delhi, 3,156 million litres of water (MLD) is supplied against the requirement of 4,158. But around 40% of the supply is lost in distribution resulting in a much wider gap between demand and supply than what's recorded.

"In official records, many cities might be getting adequate water. But because of faulty engineering and poor maintenance, the actual availability is much less," said Dilip Fouzdar, a water resource management professional.

He added that though Mumbai gets good rains in comparison to many other big cities, very little of this is actually harvested. "A robust system to recharge ground water can make the city avoid any water shortage," Fouzdar said.

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. But the deeper problem is one of short-sightedness, they said — governments wake up to water demand in a city after the situation has become acute. One such example is Gurgaon, where a major water channel was built almost 15-20 years after large-scale development happened.

The government records show 10 major cities in the country either meet daily water requirements or have surplus supply. Nagpur tops this list, reporting 52% extra supply while Punjab's industrial city, Ludhiana, has 26% surplus supply. Other cities managing to meet their water demand include Vadodara, Rajkot, Kolkata, Allahabad and Nasik.

What's also a cause for concern is that majority of the cities are depending on water sources from outside.

In Kochi, the daily water demand is 274 MLD while the supply is 250 MLD per day. Officially, daily water supply in the city is enough to meet almost 90% of the demand provided there is no loss or leakage in distribution.

6 charts that explain India’s water crisis

The demand for water is set to outpace supply by a wide margin

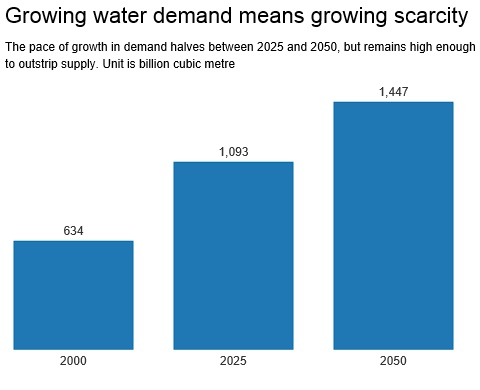

With demand for water expected to rise further, the future appears extremely uncertain. The forecast of a below normal monsoon for the second consecutive year has brought the focus on the perilous state of water resources in the country, but India’s water crisis has been in the making for a long time. The rapid growth of population and its growing needs has meant that per capita availability of fresh water has declined sharply from 3,000 cubic metres to 1,123 cubic metres over the past 50 years. The global average is 6,000 cubic metres. As water demand is expected to rise further, the future does not appear rosy.

Future projection

The demand supply mismatch is more severe in certain areas. In urban areas, where the demand of 135 litres per capita daily (lpcd) is more than three times the rural demand of 40 lpcd, the scarcity assumes menacing proportions. Already, Delhi and Chennai are fed with supply lines stretching hundreds of kilometres. According to projections by the UN, India’s urban population is expected to rise to 50% of the total population by 2050. This would mean 840 million people in the most water-starved parts of the country compared with 320 million today. The issue of inequity in water availability has already proved to be fertile ground for several inter-state and intra-state disputes, and unless mitigating steps are taken now, these conflicts would only escalate.

Future projection breakup

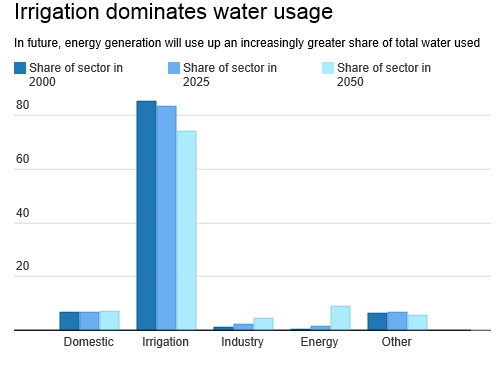

By 2050, energy generation is set to assume a much larger proportion of water usage. This should further nudge India towards renewable resources since thermal power plants are highly water-intensive and currently account for maximum water usage among all industrial applications. In order to match rapidly increasing demand, India needs to make judicious use of its two sources of fresh water — surface water and groundwater. Surface water — with rivers as its main source — is being relentlessly utilised through dams. These dams have robbed some rivers of their usual water flow, while diverting the course of others. As much as 55% of India’s total water supply comes from groundwater resources, which is also a cause of concern. Unbridled exploitation by farmers has led groundwater levels to plummet dangerously across large swathes of the countryside. Groundwater is critical to India’s water security. Irrigation, of which over 60% comes from groundwater, takes up over 80% of total water usage in India. Besides, nearly 30% of urban water supply and 70% of rural water supply comes from groundwater.

Pattern of ground water usage

The absence of rational water policies have led to the relentless exploitation of groundwater resources. Politicians looking to please the large farm vote-bank have provided massive subsidies on equipment and electricity required to mine groundwater. “By far the most powerful factor, which explains why groundwater irrigation grew faster in India than elsewhere, is the regime of flat rate tariff and power subsidies that India has introduced since the beginning of Green Revolution,” a 2012 study by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) said.

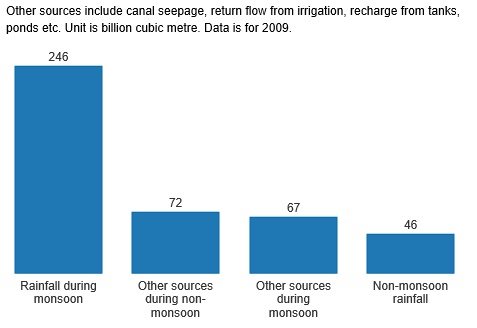

Groundwater recharge

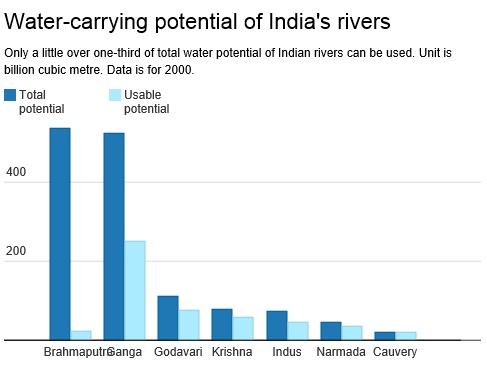

While India is blessed with some of the largest river systems in the world, a significant part of this water is rendered unavailable for use due to natural circumstances. For example, Brahmaputra has the highest total water potential of all rivers in India, but only about 4% of this can be successfully used because the mountainous terrain through which it flows makes further extraction impossible.

Rivers

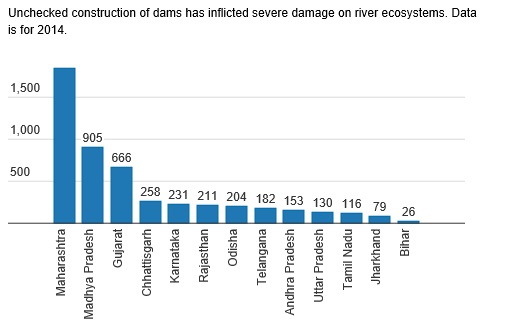

Of the total potential of nearly 1,900 billion cubic metres (bcm) in India, only about 700 bcm can be utilized. The use of surface water is also affected by dams. With over 5,000 dams, India is behind only China and US on this count. While facilitating irrigation and electricity generation, the dams are adversely affecting water quality in the country.

Dams

“The irrigation benefits accruing from dams are largely illusory and far less than what is expected when they are planned,” said Tushar Shah, a water expert and senior fellow at IWMI. “Eventually, dams turn out very unattractive from a socio-economic perspective.”

Several scientific studies, including one by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2001, emphasize that dams have two main adverse effects on rivers. First, dams alter the chemical content and temperature of water. Water stored by dams has a temperature distinctly different from the rest of the river, and being stagnant, picks up unwanted things such as sand, besides encouraging algal bloom. Second, dams reduce the natural quantity of water flowing through downstream areas.