Water: Drinking water, rural water and its availability, India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Water crisis in major cities

22 of India's 32 big cities face water crisis

Dipak Kumar Dash, TNN | Sep 9, 2013

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. (TOI photo by Balish Ahuja)

NEW DELHI: Water scarcity is fast becoming urban India's number one woe, with government's own data revealing that residents in 22 out of 32 major cities have to deal with daily shortages.

The worst-hit city is Jamshedpur, where the gap between demand and supply is a yawning 70%. The crisis is acute in Kanpur, Asansol, Dhanbad, Meerut, Faridabad, Visakhapatnam, Madurai and Hyderabad — where supply fails to meet almost 30% of the demand — according to data provided by states which was placed in the Lok Sabha during the recently-concluded Parliament session by the urban development ministry.

The figures reveal that in Greater Mumbai and Delhi — which have the highest water demand among all cities — the gap between demand and supply is comparatively less. The shortfall is 24% for Delhi and 17% for Mumbai. However, the situation is worse than that.

For example, in Delhi, 3,156 million litres of water (MLD) is supplied against the requirement of 4,158. But around 40% of the supply is lost in distribution resulting in a much wider gap between demand and supply than what's recorded.

"In official records, many cities might be getting adequate water. But because of faulty engineering and poor maintenance, the actual availability is much less," said Dilip Fouzdar, a water resource management professional.

He added that though Mumbai gets good rains in comparison to many other big cities, very little of this is actually harvested. "A robust system to recharge ground water can make the city avoid any water shortage," Fouzdar said.

Experts say that population of cities such as Jamshedpur, Dhanbad and Kanpur have increased manifold, resulting in increased demand for water. But the deeper problem is one of short-sightedness, they said — governments wake up to water demand in a city after the situation has become acute. One such example is Gurgaon, where a major water channel was built almost 15-20 years after large-scale development happened.

The government records show 10 major cities in the country either meet daily water requirements or have surplus supply. Nagpur tops this list, reporting 52% extra supply while Punjab's industrial city, Ludhiana, has 26% surplus supply. Other cities managing to meet their water demand include Vadodara, Rajkot, Kolkata, Allahabad and Nasik.

What's also a cause for concern is that majority of the cities are depending on water sources from outside.

In Kochi, the daily water demand is 274 MLD while the supply is 250 MLD per day. Officially, daily water supply in the city is enough to meet almost 90% of the demand provided there is no loss or leakage in distribution.

Delhi

Drinking water

See graphic

in the rural areas

Funds decline after 2013-14

The Times of India, Apr 13 2016

Funds for rural water drying up

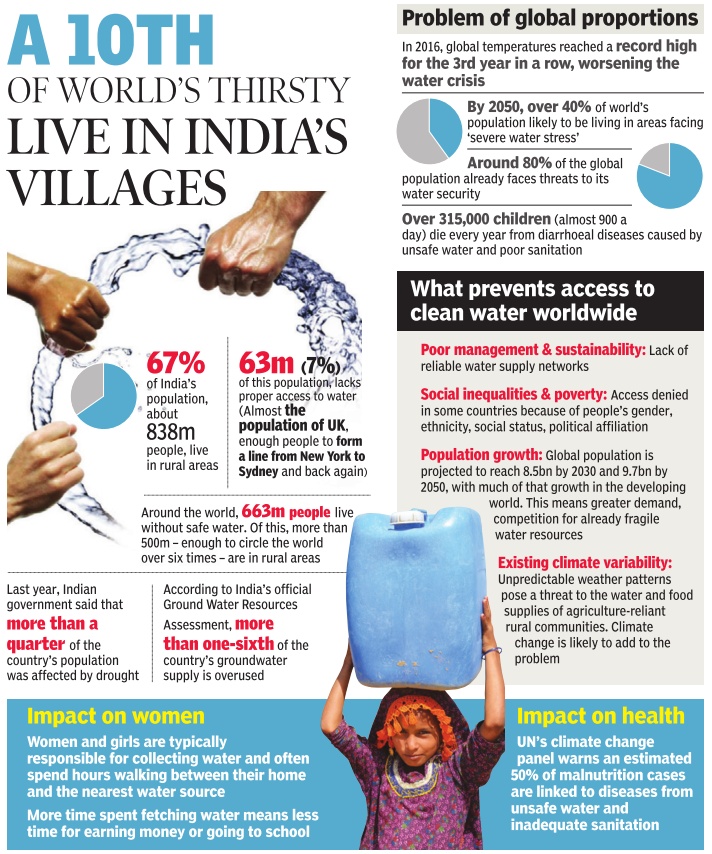

Dipak Dash The budgetary allocation for drinking water in rural areas has been decreasing since 2013-14 even as certain parts of the country reel under acute shortage of water for the second consecutive year.

The maximum reduction was registered in 201516 and 2016-17 owing to a greater devolution of funds to states under the 14th Finance Commission.

An analysis of the budgetary allocation for drinking water in rural areas over the past four financial years shows that the maximum amount earmarked was approximately Rs 10,500 crore in 2012-13.The allocation was the lowest in 2015-16 at Rs 4,260 crore.Though it has been hiked for this fiscal, the increase is negligible.

Sources said the issue was discussed at a review meeting on drought chaired by the cabinet secretary on Monday . A fact causing worry is that many projects already started may get impacted because of lower central support.

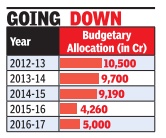

Rural population with no clean drinking water , March 2017

See graphic

Mark-II Handpump

India Today.in , Water,Water,Everywhere “India Today” 15/12/2016

1978

Mark-II Pumps

Water, water, everywhere

At a time when electricity had not quite reached the far-flung villages of India, the only way to access water-especially in times of drought-was to source it manually from wells. At first, wells were dug by hand; later, as powerful drill machines were developed, bore wells became the norm. To tap groundwater sources effectively, the Government of India joined hands with UNICEF to develop a more efficient manual handpump than the one in existence. After several rounds of trials, the government decided to adopt widespread installation of the 'Mark-II' pump. UNICEF agreed, spreading the technology to many other developing countries as well. The Mark II was based on the 'Sholapur pump', the most durable of its time, designed initially by a self-taught Indian mechanic. By the mid-1990s, five million pumps had been manufactured and installed. An improvement, the Mark III was also developed; these manual pumps are now exported to about 40 countries. Technological innovation has led to further upgrades as well, transforming the manual pump into a solar-powered thermal siphon pump in many places where piped water supply to homes is still a distant dream.

How Rajasthan’s desert tribes get clean water

Ramgarh (West Rajasthan) A traditional system of harvesting rainwater, beris have been lifesavers for both humans and animals in these parts for centuries. Shaped like a matka (pitcher), the shallow wells are dug up in areas with gypsum or bentonite beds that prevent rainwater from percolating downwards. Instead the water gets guided to the wells through capillary action.

“Last year, Ramgarh and neighbouring villages barely received any rain. But, even so, the beris were fully charged. One can draw 10,000 litres of clean water daily; it gets replenished overnight,“ says Chatar Singh (56), local eco warrior with masterly knowledge of water conservation in deserts.

His initiatives, with those of Sambhaav, an NGO that helps to restore aquifers, have led to the digging of dozens of new beris and revival of others that had fallen into disuse. The locals' trek for drinking water is not so long anymore.

The importance of beris gets underlined by what unfolds kilometres away . Water from the humongous Indira Gandhi canal gathers in a pond-like structure on its way to the filtering unit. The water, full of algae, looks unfit for consumption. Yet tractors line up to ferry it away in large cans. “Hum yahi pani peete hain (We all drink this water),“ says Suraj Singh Bhati, Class X, here to ferry water home.Near the Sagarmal Gopa branch of the canal a cow's rotting carcass lies.

On the outskirts of Netsi village, 23 beris are in use. The village has a huge cement tank that stores water released from the IG canal. But most women trek a kilometer to Viprasar, where the beris are.“Most of us drink the beris' water,“ says Mala Devi. Water from the IG canal has undeniably eased their woes but most villagers told TOI that taps often run dry .“We got water after a gap of five days,“ said Guddi of Ekalpar village. Traditional Netsi beris were made of wood. “They'd rot after a year. The new beris are built with long-lasting blocks of yellow stones that Jaisalmer is known for,“ says retired armyman Jitu Singh.

Success in these water harvesting projects resulted from partnering with locals. Netsi villagers offered the labour required to make the beris functional.Chatar says villagers were first motivated, while Sambhaav provided materials.

Chatar, who used to teach children of the tribal bhil community in Ekalpar and Dobalpar, once regarded the area's poorest villages, has over the last decade, worked on water conservation alongside Farhad, who routinely visits these villages. Part of their work is to help the bhils learn the traditional art of khadeen, a form of cultivation in arid regions where the ground's moisture is harnessed to grow wheat, mustard and black gram in the main. “We help them help themselves,“ says Farhad.

The bhils, largely a hunting community, would be asked to shift from one place to another by the local administration.“They did not know how to harness water. Sometimes they would lie down on the field to stop rainwater from escaping,“ recalls Chatar Singh, influenced by environmentalist Anupam Mishra's seminal book `Rajasthan Ki Rajat Boondein' (The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan).

The bhils were taught toba: a way to store rainwater for drinking, dhora: a technique to store rainwater for irrigation and chhapai: a method to use a `wall' of bushes to stop the spread of desertification. “We didn't know how to grow crops,“ says Padma Ram (60), a bhil who owns 75 bighas. In 2015, he earned Rs 3 lakh growing black gram.Such examples abound. The two bhil villages now boast 30 motorcycles and 15 tractors; unthinkable few years ago.

A distance from his village, Padma is building a mound three feet high, over 500 feet long. “The dhora will trap rain water,“ he says. Rain arrives late in Jaisalmer, plays hookey in Ramgarh at times. But the bhil is an optimist. “It will rain one day,“ he says. “When it does, I want to trap every drop.“

Karnataka, 2017: many areas depend on AP

Naveen Y, Karnataka's driest villages bank on Andhra for water, June 2, 2017: The Times of India

Villagers skip work, forego wages to make trips to the next state for both family & livestock's daily needs

Every morning, 42-year-old Lakshmi of Kondapura in Karnataka's Pavagada taluk crosses the inter-state border into Chikkanaduka village in Andhra's Ananthpur district and returns home with a pot of water. It's a 10km walk to and fro, and it means the daily wager has to forego her earnings. But the mother of two says: “We are lucky, because the neighbouring villages in Andhra Pradesh have sufficient borewells. The people there are supporting us.Otherwise, it is very difficult for us to live here. Thank God there's no border wall between the two states.“

The nearly 300 families living in Kondapura, 150km from Bengaluru, are facing acute water scarcity as drought ravages the entire region for the third year in a row. The weekly water tanker sent by the taluk administration is barely adequate.

The three government borewells in the village have dried up. Although there are two private borewells, the landlords refuse to share water. People save every drop for drinking and baths are a once-a-week luxury in Kondapura as well as neighbouring Vellur, Nagenahalli, Chikkanahalli and Siddapura villages in Pavagada taluk -the second-most arid region in the country after the Thar desert.

Water has become a perennial problem. “None of the officials bother about us,“ says Lakshmi bitterly .Parvathamma, her companion in the 10km water-walk, says: “Water is making us poor. We used to work as labourers and get daily wages, but we cannot work as we have to trek several hours for water.“ It's become a family occupation. “While I get two pots of water in the morning, my husband and two kids get six pots of water on our bicycle in the evenings,“ Parvathamma says. “Each family in the region owns a bicycle, basically used to transport water pots.“ Another village woman, 35-year-old Bhagya points out that villagers have to share the water with their cattle.

The water scarcity is also drying up the marriage prospects of local boys.Nagendra, a young college graduate from Chikkanahalli, says it's a struggle for families to find brides.“People are not ready to get their daughters married to boys in the village because there is no water. They prefer to seek bridegrooms on the other side of the border as water is not a problem there.“

Despite similar topography, how do Andhra villages have water while their Karnataka neighbours have none? The villagers attribute it to the Andhra government's resolve to solve the water problems of its tail-end areas. The HandriNeeva Sujala Sravanthi project sources Krishna wa ters through the Srisailam reservoir and supplies to Madakasira and adjoining areas on theder. The Andhra government has also built check dams and artificial water recharge structures.

Bhagya points out: “The borewells of Andhra villagers have water, and it's great that they are willing to share it with us. Hope our government wakes up soon.“

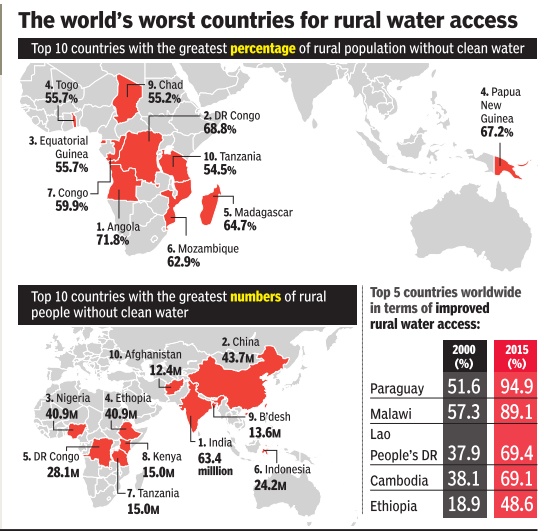

Charts explaining India’s water crisis

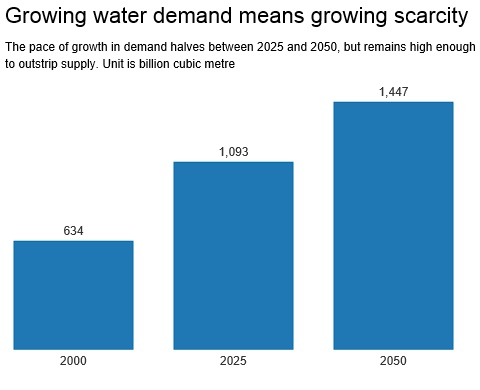

The demand for water is set to outpace supply by a wide margin

With demand for water expected to rise further, the future appears extremely uncertain. The forecast of a below normal monsoon for the second consecutive year has brought the focus on the perilous state of water resources in the country, but India’s water crisis has been in the making for a long time. The rapid growth of population and its growing needs has meant that per capita availability of fresh water has declined sharply from 3,000 cubic metres to 1,123 cubic metres over the past 50 years. The global average is 6,000 cubic metres. As water demand is expected to rise further, the future does not appear rosy.

Future projection

The demand supply mismatch is more severe in certain areas. In urban areas, where the demand of 135 litres per capita daily (lpcd) is more than three times the rural demand of 40 lpcd, the scarcity assumes menacing proportions. Already, Delhi and Chennai are fed with supply lines stretching hundreds of kilometres. According to projections by the UN, India’s urban population is expected to rise to 50% of the total population by 2050. This would mean 840 million people in the most water-starved parts of the country compared with 320 million today. The issue of inequity in water availability has already proved to be fertile ground for several inter-state and intra-state disputes, and unless mitigating steps are taken now, these conflicts would only escalate.

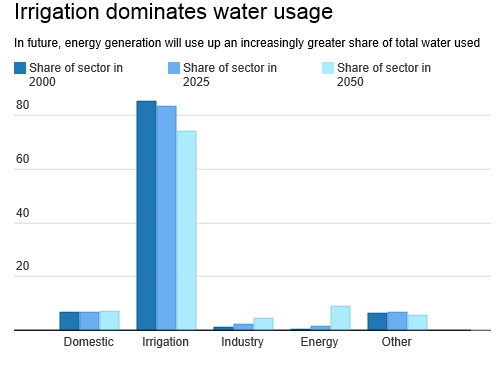

Future projection breakup

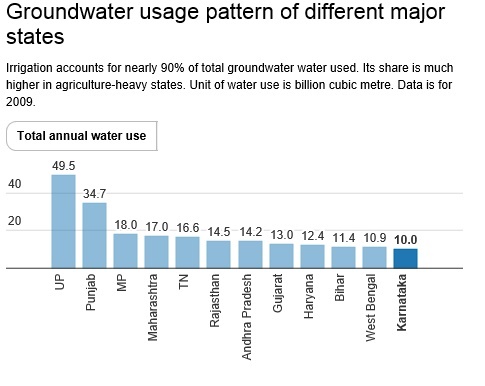

By 2050, energy generation is set to assume a much larger proportion of water usage. This should further nudge India towards renewable resources since thermal power plants are highly water-intensive and currently account for maximum water usage among all industrial applications. In order to match rapidly increasing demand, India needs to make judicious use of its two sources of fresh water — surface water and groundwater. Surface water — with rivers as its main source — is being relentlessly utilised through dams. These dams have robbed some rivers of their usual water flow, while diverting the course of others. As much as 55% of India’s total water supply comes from groundwater resources, which is also a cause of concern. Unbridled exploitation by farmers has led groundwater levels to plummet dangerously across large swathes of the countryside. Groundwater is critical to India’s water security. Irrigation, of which over 60% comes from groundwater, takes up over 80% of total water usage in India. Besides, nearly 30% of urban water supply and 70% of rural water supply comes from groundwater.

Pattern of ground water usage

The absence of rational water policies have led to the relentless exploitation of groundwater resources. Politicians looking to please the large farm vote-bank have provided massive subsidies on equipment and electricity required to mine groundwater. “By far the most powerful factor, which explains why groundwater irrigation grew faster in India than elsewhere, is the regime of flat rate tariff and power subsidies that India has introduced since the beginning of Green Revolution,” a 2012 study by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) said.

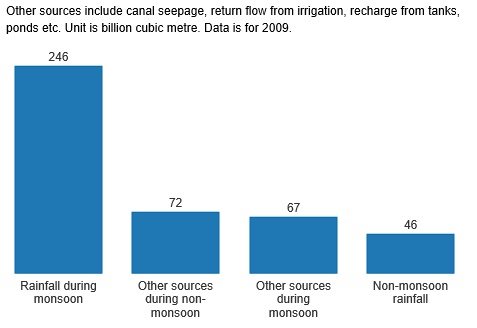

Groundwater recharge

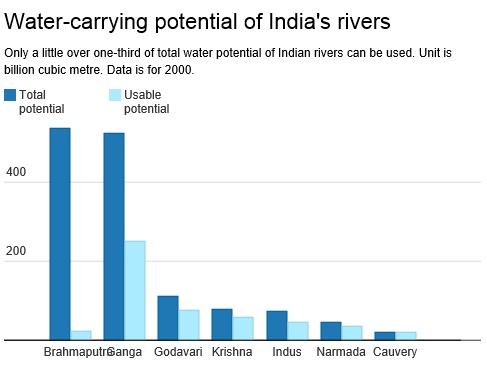

While India is blessed with some of the largest river systems in the world, a significant part of this water is rendered unavailable for use due to natural circumstances. For example, Brahmaputra has the highest total water potential of all rivers in India, but only about 4% of this can be successfully used because the mountainous terrain through which it flows makes further extraction impossible.

Rivers

Of the total potential of nearly 1,900 billion cubic metres (bcm) in India, only about 700 bcm can be utilized. The use of surface water is also affected by dams. With over 5,000 dams, India is behind only China and US on this count. While facilitating irrigation and electricity generation, the dams are adversely affecting water quality in the country.

Dams

“The irrigation benefits accruing from dams are largely illusory and far less than what is expected when they are planned,” said Tushar Shah, a water expert and senior fellow at IWMI. “Eventually, dams turn out very unattractive from a socio-economic perspective.”

Several scientific studies, including one by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2001, emphasize that dams have two main adverse effects on rivers. First, dams alter the chemical content and temperature of water. Water stored by dams has a temperature distinctly different from the rest of the river, and being stagnant, picks up unwanted things such as sand, besides encouraging algal bloom. Second, dams reduce the natural quantity of water flowing through downstream areas.