Nagpur district: Archaean Rocks

This section has been archived from a govt document for the excellence of its content. the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be acknowledged in your name. |

Contents |

Archaean Rocks

The Archaeans of Nagpur district are comprised of two distinct lithological units; the older unit comprising gneisses and schists resulting from repeated metamorphism of ancient sediments (similar to Dharwar formation of Southern India) and a younger group of gneisses representing perhaps a granitic intrusion into above metasediments. As both these rock units have suffered intense deformation and metamorphism it is difficult to distinguish them from each other and consequently are generally grouped together as unclassified metamorphic and crystalline series.

Sausar and Sakoli Series

Racks of the older metasedimentary group have been mapped in great detail and named Sausar series (occurring in the Northern ‘Nagpur-Chhindwada' region) and Sakoli series (occurring in the Southern' Nagpur-Bhandara' region); the latter, viz., Sakoli series are assumed to be an upward continuation of the farmer, viz., Sausar series. The Sausar series is further subdivided into stages mostly on their litholoagy; the Lohangi, Mansar and Chorbaoli being important in view of their containing manganese ore zones. The rock types comprising these series include biotite-gneiss, quartz-pyroxene-gneiss, calcyphyre, crystalline limestone, quartzite, mica-schist, hematite-schist, pegmatite and various manganiferous rocks known as Gondite.Gondite (named after the aboriginal tribe ‘Gonds’ found in these areas) is a rock composed of quartz and manganese Garnet ‘spessar-tite’.

Many other rock types carrying rare species of manganese minerals such as Blanfordite-a manganese pyroxene (from Kachurwahi and Ramdongri), Vrendenburgite-a strongly magnetic manganese ore (from Beldongri), Hollandite-crystalline form of psilomelane (from Junawani) and Beldongrite-black pitch like mineral regarded as an alteration product of spessartite, have been grouped under the Gondite series. Of the other minerals found in the manganiferous rocks of the region, Sitaparite Chiklite, Winchite, Juddite, Rhodonite and Piedmontite deserve mention. An excellent exposure of crystalline limestone containing piedmontite nodules occurs in the Pench river at Ghogra (Gokula) about 3 km. north-east of Parseoni.

Streaky-Granitiegneisses

Rocks of the younger group comprise coarse grained graniticgneisses, prevalent amongst which, is a streaky biotite gneiss which at places covers large areas. These are, however, distinguished from schists and gneisses of sedimentary origin (Sausar series) in view of their not being confined to any particular horizon, and occurring adjacent to any of the stages of the Sausar series. Another feature of these rocks is the occurrence in them of coarse pegmatite intrusive. Based on these and other lines of field evidence, it is thought that these rocks are intrusive into the Sausar series.

Structure of Archaean Rocks

The Archaean rocks of this district have a very complex structural pattern. The Sausar series (northern belt) generally dips towards south-south-east or south and the Sakoli series to the north-north-west while the middle or axial region may be al zone of faulting or overthrust. In the Sausar series the southern part is composed of isoclinal folds with steep (50º-80º) dips to south; in the middle strip the folds are recumbent, with 30° to 60° dip to the south, while the northern strip shows thrust sheets.

There are many steep dipping strike faults which are generally thrust faults. Three ‘Nappe’ units have been recognised in the Nagpur-Chhindwada region at Sapghota, Ambajhari and Deola-par from west to east all of them having a low southernly dip. ‘Nappe’ is a structure wherein a sheet of rocks has been tectonically transported far from its original site. Earlier folds in Sausar series have been refolded by late stage deformation and the resulting ‘cross-fold’ structure is seen at Ramtek, Junawani and Deolapar. Lineations of various kinds are well developed in the Archaean rocks of the district, all of which plunge 20° to 30° towards east.

Gondwana group

Rocks referable to the Talchir, Barakar and Kamthi stages of the Gondwana system of fluviatile and lacustrine origin were deposited in troughs, generally produced by faults, which in many cases form he boundary of Gondwanas with older rocks and therefore known as ‘Boundary fault’. The Kelod-Kamptee line which marks the north-east boundary of Kamthi beds with Archaeans is a boundary fault.

The Gondwana formations have been affected by other minor faults as revealed in several drill holes put down to prove the existence of coal seams around the towns of Kanhan and Kamptee. There is a marked unconformity between the Barakars and Kamthis; during the time interval indicated by this unconformity, Barakars were partially or completely eroded away in some areas and the Kamthis rest directly over the Talchirs. At other places absence of Barakar outcrops is due to overlap (extension of a strata in a conformable sequence beyond the boundaries of those lying beneath) by Kamthis.

Talchirs

Talchir beds are exposed at Kodadongri (north of Patansaongi) and 9 km. north of Nagpur near Suradevi hills, while to 8 km. north of these hills minor exposures are seen. Talchirs comprise green shales and sandstones with minor intercalations of clay and rest unconformably with a basal conglomerate over the Archaean rocks.

Barakars

Coal-hearing Barakar beds consisting of white and grey sandstones and grits, fireclays and carbonaceous shales are exposed in Tekadi-Silewada-Patansaongi and Bhokara-Chakki-Khapa tract. They are also reported from below the Lameta beds near Umrer. Barakar outcrops are generally lacking in the district, being either overlapped by Kamthis or concealed under the alluvium. About 200 metres north of Kanhan Railway Station a drill hole has revealed Barakars beneath the alluvium.

Kamthis

These rocks occupy an area which is bounded by Kelod-Kamptee line towards north-east along which Kamthis have been faulted against Archaeans. Southwards they stretch upto Bhokara, 6 km. north of Nagpur. The western boundary is the irregular edge of the Deccan basalts. At Silewada, about 8 km. northwest of Kamptee, a low range of hills is composed of Kamthis. Detached from above, two inliers are seen in the trap area to the west. One of these (about 14 kill. long by 6 wide) lies to the north-east of Bazargaon and the other roughly 54 km. north-west of Nagpur at Ghorkheri (6 km. long by 4 wide).

Kamthis trend in west-north-west-east-south-east direction with 5° to 30° dip towards south-south-west and their estimated thickness is about 1,500 km. Predominantly composed of soft and coarse grained sandstones, Kamthis also contain fine grained mica-ceous sandstones, hard and gritty sandstones and homogeneous and compact shales. Bazargaon inlier contains considerable thickness of conglomerates composed of white quartz pebbles set in a matrix of grit. Interstratified with this conglomerate is a fine red argillaceous sandstone.

Fossil flora include species of Phyllotheca, Vertebraria, Pecopteris, Gangamopteris, Angiopteridium, Macrotaeniopteris, Noeggera- thiopsis and Glossopteris. The best known localities for fossils in Kamthis are the stone quarries at Silewada and Kamptee.

Lametas

Lametas, also known as Infratrappeans for their subjacent position to traps (Deccan basalts), are fresh water deposits which rest horizontally over the older Gondwana and Archaean rocks with an unconformity. Lametas which rarely attain a thickness up to 8 metres grade from calcareous sandstones to sandy limestones with intercalations of chert and clay. These occur at the foot of Kelod and Sitabuldi (Nagpur) hills, west of Adyal and at Ketapur. A large spread of these rocks is situated immediately to the west of Umrer. Lametas have also been found fringing the trap outliers in the north-west corner of the district. Fossil Mollusca found in the beds at Nagpur are Melania, Paludina and Corbicula and Physa.

Deccan basalts (Traps) and Intertrappeans

The western part of the district is covered by layers or doleritic and basaltic lavas, commonly known as ‘traps’ because of steplike appearance of their outcrops, the term being of Scandinavian origin. Apart from the main area to the west, several outliers are found north-west of Bhivagad, whilst the southern end of the tongue of trap separating the Pench Valley in Chhindwada district just crosses the border into Nagpur.

These traps are of fissure-eruption type, i.e., they welled up through long narrow fissures in the earth's crust and flowed out as horizontal layers one over the other. Individual flows (layers) have been traced for distances of 100 km. in this district. Some layers are hard and compact while others are soft, vesicular or amygdaloidal having cavities filled with secondary calcite,, zeolite and quartz. Columnar joints, sheeting and spheroidal weathering are characteristic of these rocks.

The Deccan traps belong to ‘Plateau basalt’ type, essentially composed of plagioclase (mostly labradorite) and augite with some magnetite. Palagonite is abundant in the basalts near Nagpur. These rocks are generally dark grey in colour having a specific gravity of 2.9.

Intertrappeans

Layers of fresh water sedimentary rocks, are interbedded with the Deccan basalt flows to the west of Nagpur. Such intertrappean beds occur near Dhapewada, between Bhokara and Mahu-jhari, Takli, Telankhedi and Sitabuldi. They range in thickness from a few centimetres up to two metres and are composed of cherts, impure limestones and pyroclastic material including trap detritus.

Numerous fossils have been collected from these rocks, the most famous locality being Takli. The collection includes Replitian bones, remains of a fresh water Tortoise, Fish-scales, Coleoptera, Entomostracans. Dinosaurian tooth similar to Mega-losaurs and following fresh water mollusca-Ballinus. Melania, Limnaea, Succinea, Paludina, Phvsa and Vilvala. Fossil flora includes over 50 species of fruits and seeds, 50 species of exogenous and endogenous leaves and stems, some of the latter being six feet in girth, roots and Chara.

Soil

In the Archaean area the rocks are hidden beneath a considerable thickness of alluvial soil, deposited by the tributaries of the Kanhan and the Wainganga rivers. In the trappean area the soil is usually the black cotton soil known as regur with Kankar, which is also found in the soils on the Archaean areas.

Useful Rocks and Minerals

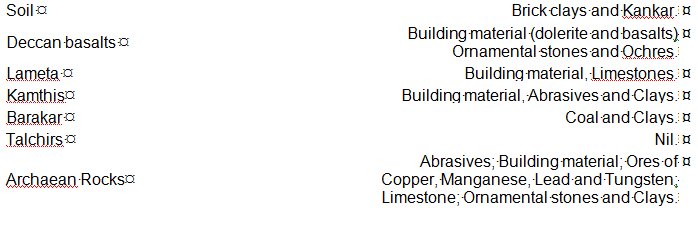

Industrial minerals and rocks found in various geological formations of the district are tabulated below:

Brief description of the useful minerals and rocks of the district is as follows:

Abrasives

Various types of quartzite in the Archaean formations and some of the sandstones of the Kamthi stage are quarried for making millstones. Garnets found in abundance in the Archaean garnetiferous mica schists may be utilised as an abrasive.

Building Material

The alluvial tracts of the Kanhan and the Wainganga rivers and their tributaries yield excellent brick-making clay, while the Deccan basalts provide excellent building stone and are quarried at several places. The Lameta limestones have been extensively used for making railway bridges in the district. Sandstones, suitable for fine carving is obtained from quarries in Kamthi beds at Silewada and Kamptee. The bridge over Kanhan at Kamptee is of this rock.

The crystalline limestones occurring near Chor-baoli and Baregaon would make fine marbles, while beautifully marked serpentine marbles are found near Khorari. Slightly micaceous quartzites forming the Ramtek range of hills may be used as building stones. Kankar occurring extensively on the soil mantle is locally burnt for making lime used in mortar for construction purposes.

Clays

Pottery clays are worked around Shemda. Chorkhairi, Khairi and Bazargaon. They all have medium to good plasticity, little shrinkage and give light cream colour when burned. The quarries at Chorkhairi and Shemda are 6 to 14 metres deep.

Coal

Exploratory drilling near Kanhan Railway Station and just west of Kandri has proved the existence of several coal seams up to a thickness of 10 metres. These seams were found in Barakar beds (concealed beneath Kamthi beds) at various levels down to 100 metres from the surface. A shaft sunk near Tekadi passed a four-metre seam of workable coal containing 21% ash, having a calorific value of 9408 B.T.U.

This seam is estimated to yield about 17.5 million tons of coal of which perhaps 13 million tons can be exploited; however, so far it has been proved that only about a million tons of this can be taken. Coal seams have also been met with in the bore-holes put down at Sonegaon (1.6 kill. west of Umrer) where Gondwana rocks are concealed below Lameta beds.

Nearly 300 million tons of coal of which more than 150 million tons is of first grade and the rest of third grade has been proved in an area of 10.36 km.2 in the Kamptee Saoner belt. The indicated reserves in this belt alone are of the order of 1,000 million tons. Several other coal fields in Nagpur district are likely to be proved and the expected reserves may be more than double the above quantity. ‘It will be interesting to note that the coal output in the Nagpur district increased from 70,539 metric tons in 1959 to 89A21 metric tons in 1961.’ (Administration Report, Directorate of Geology and Mining, Maharashtra State, for the year 1960-61, p. 19)

Limestone

The Lameta beds at Kelod and Chicholi contain workable limestones and several bands of crystalline limestones are found in the Archaean rocks near Koradi, Baregaon and in the north-east corner of the district. Much of these limestones are, how-ever, too impure to be used as a source of lime. Detailed prospecting may, however, bring to light deposits pure enough for burning into lime.

Manganese

It was in 1900 that the extraction of manganese ore started in the district. Some of the most famous mines are located in the district. The ore bodies occur in rocks of the Gondite series (forming a portion of Sausar series), regarded as metamorphosed manganiferous sediments of Pre-Cambrian age.

Much of the workable ore bodies occur as lenticular masses and bands intercalated in quartzites, schists and gneisses and appear to have been formed at least in part, by chemical alteration of the rocks of Gondite series. The ore bodies are often well bedded parallel to the strike of the enclosing rock and several of them are often disposed along the same line of strike.

An example is the line of deposits stretching from Dumri Kala to Khandala for about 20 km. and includes the valuable deposits of Beldongri, Lohdongri, Kachurwahi and Waregaon. Along with the enclosing rocks, the ore bodies have suffered repeated foldings. The deposits attain great dimensions as at Manegaon where it is about 2 km. long, the thickness, however, never exceeds 16 metres. The depth to which these ore bodies may persist is unknown but it is certain that in many cases they persist from 40 to 140 metres below the outcrop.

The ore consists essentially of braunite, psilomelane and cryptomelane occasionally with hollandite and vrendenburgite. Frequently the ore bodies pass both along and across the strike into partly altered or fresh members of Gondite series. Manganese deposits of above types are mainly being worked at Kodegaon, Gumgaon, Ramdongri, Risala, Nandgondi, Kandri, Mansar, Parsoda, Borda, Parseoni, Bansinghi, Satak, Beldongri, Nagardhan, Nandapuri, Lohdongri, Kachurwahi, Ware-gaon, Khandala, Mandri, Panchala, Manegaon, Guguldoh and Bhandarbori. At Sitagondi and Dumri pebbles and fragments of ore not ‘in situ’ have been found.

A second type of ore associated with piedmontite and occurring as bands and nodules in crystalline limestones is found at Moh-gaon Pali, Gokula, Mandvi Bir, Junewani and Junapani. These deposits are not large enough for profitable working, except the one at Junewani where ore bed is of much greater thickness.

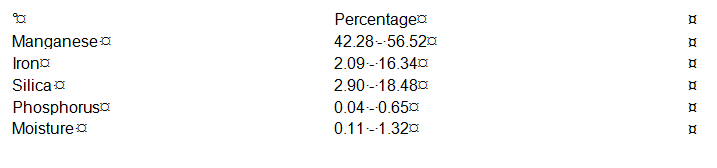

The quality of the ore in the district may be judged from an average of 30 samples, analysis of which is given below:

The ore from Pali is particularly suitable for the glass industry. Much of the ore produced in the district is exported, while a part is employed in the indigenous Ferro-manganese industry. The reserves of manganese ores of all grades in the district are of the order of 3,048,000 metric tons (3 million tons).

Ochres

Yellow Ochre is associated with the Deccan lava flows at Kalmeshwar, and is locally used as a cheap distemper.

Ornamental Stones

The large variety of marbles that occur in the Archaean rocks of north-eastern portions of the district and the Gondites with Rhodonite and Spessartite in the manganese belt provide excellent ornamental stones. The Rhodonite has a beautiful rose pink colour, often marked with black veins and spots due to alteration and is often spotted with orange due to the inclusion of Spessartite. Agates and Chalcedony found in the trappean portion of the district, may be cut and polished into ornamental objects of considerable beauty.

Minor occurrences of other ores

Tungsten Ore

Wolfram, associated with traces of Scheelite is found 1.2 km. west of Agargaon (51 km. south-east of Nagpur) on a low ridge on the right bank or the Kanhan river. The ore occurs in quartz veins intruding the phyllitic tornaline schists belonging to Sakoli series and can be traced for about 1,300 metres. Maximum width of a cluster of ore is about a metre.

Copper and Local Ores

Chalcopyrite occurs in a basic dyke at Mahali about 6 km. north-east of Parseoni while specks of the same mineral occur in quartzose matrix in a cutting near Mandri. Fragments of Galena (Lead ore) are reported to have been found at Nimbha (27 km. north of Nagpur).

Ground water

On the basis of the mode of occurrence of ground water, which is controlled by the type of geological formation present, the district can be classified into three distinct areas as detailed below :

Archaean area

The ground water may be capped in the weathered and jointed zones in these rocks, generally within 80 metres of the surface. The granite-gneisses and schists are commonly weathered to depths of 30 metres and this weathered mantle though constituting a large reservoir is not a specially permeable zone. The wells dug in this zone tap water at depths varying from 8 to 30 metres from the surface. A well of about 3 metres in diameter may afford a sustained daily yield. The quartzites and marbles are the poorest water-bearing rocks. Being massive they are devoid of permeable zones for circulation of water.

Gondwana (including Lameta) area

Although the Talchir shales and Lameta beds are compact and impermeable, they carry some water along the joint and bedding planes and in the weathered mantle. The Barakars and Kamthis generally consisting of medium to coarse-grained friable sand-stones constitute the most important aquifer in the district. In fact, the water-bearing Kamthis are dreaded by coal miners in the adjacent district who take special precautions not to puncture Kamthis so that they may not flood the mine. In these formations dug wells are capable of yielding up to 4,550,000 litres (one million gallons) a day and tube wells should be a success.

Trappean area

Deccan basalts are poor water-bearing rocks. The weathered basalt ‘Mooram’ joint planes and flow contacts widened by weathering collectively constitute the ground water reservoir. Generally basalts hold very little or no water below 50 metres from the surface.