Sufi poetry (Sufiyana Kalaam)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Sufism in the Punjab

Ranjha ranjha kardi hun main aape Ranjha hoyi

India Harmony Volume - 1 : Issue - 2, 2013

Sufiyana Kalaam captures popular imagination

Sufism, the inner, mystical, or psychospiritual dimension of Islam with its emphasis on equity, humanism and universal brotherhood has become uber cool in current times.

Bulleh in 21st century popular music

In 2004, popular Punjabi singer Rabbi Shergill's rendition of the abstract metaphysical composition of Bulleh Shah, Bullah ki Jaana became a raging hit in India and Pakistan

Bulleh Shah's composition again appeared in the song Bandeya Ho in the 2007 Pakistani film Khuda ke liye. The 2008 Indian movie A Wednesday, written and directed by Neeraj Pandey, had a song, Bulleh Shah, O yaar mere in its soundtrack. Bulleh Shah's composition was rewritten in this film by Irshad Kamil In the movie Raavan (2010), Gulzar used Bulleh Shah's 'Ranjha Ranjha' in one of the songs. In 2009, Episode One of Pakistan's Coke Studio Season 2 featured collaboration between Sain Zahoor and Noori, and as a result, Bulleh Shah's Aik Alif became immensely popular.

A R Rehman's Khwaja mere Khwaja and Kailash Kher's Allah ke Bandhe too have made an impact.

Sufi pop

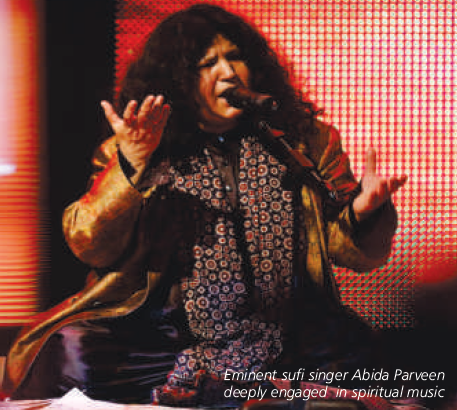

Several singers of the subcontinent including the legendary Nusrat Fateh Ali khan, Abida Parveen and youngsters like Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Zila Khan, Wadali Brothers and sufi rock bands like Junoon and Mekaal Hasan have brought the rich spirituality of sufi poetry to contemporary audiences.

Seeking through poetry

The Sufi tradition of seeking spiritual salvation, searching for the meaning of life and for God, are beautifully expressed through their poetry. Who is the Creator? What is the truth? What is the meaning of life? How can one find God? Who am I? These are some of the universal truths that the Sufis have tried to answer by disassociating themselves from worldly knowledge and deeds, and moving onto a spiritual sphere, where they are no longer bound by traditionally interpreted religious or material restrictions.

Syed Bulleh Shah (1680-1758)

It is just such a search that has been exquisitely portrayed by Syed Bulleh Shah (1680-1758) in the song 'Bullah ki jaana mein kaun'.

He, later shifted to another village- Pando kee Bhattiyyan in Qasur district. On his death, the Maulvis did not allow him to be buried in the community graveyard because of his unorthodox beliefs. Bulleh Shah is today known globally as the greatest Sufi poet of Punjab; the rich and the influential, the very class which had rejected him once, today compete with each other to be buried near his grave at Qasur (near Lahore).

This poem by Bulleh Shah typifies a spirituality that speaks of intense fervour towards God while at the same time advocating a deep human brotherhood.

If God was found by bathing and cleansing He would have been found by frogs and fish If God was found by wandering in the jungles Stray animals would have found him O Bulleh, the Lord can only be found By loving hearts – true and pure…

The Way of the Sufis in India

The Sufis came from Central Asia and the Middle East around the time the first Muslim conquerors came to India. They brought with them an unorthodox and iconoclastic form of spirituality that approached universal faith with liberal teachings and immense tolerance. The core teaching was of secularism and a simple message of the oneness of God. In the era of globalisation, the Sufis' ersatz poetry has a universal appeal.

Sufism, provides rich resources for developing theologies of inter-faith dialogue and solidarity, an urgent necessity in today's world where talk of a global 'clash of civilisations' threatens to become a frightening reality. In this regard, the works of numerous Indian Sufis is particularly significant because they lived and wrote in a multi-religious context, addressing and attracting people of different faiths—Muslims, Hindus and others. Some of them developed understanding of different faiths, besides islam, that went beyond narrowly constructed communal boundaries, defying the empty and soulless ritualism that served to divide communities from each other.

The sufis' God madness and the intense desire to be one with God often had them singing and dancing themselves into a trance. Singers like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan are able to take the audiences to the rapturous heights of spirituality through their qawwal and sufi singing. Abida Parveen too is able to combine masti (frenzy) with meditative intimacy.

The spirit of Sufism found a ready congruence in Vedanta and in the Indian "Sant tradition." The intense passion for union with God and the pangs of separation of the sufis was akin to the Vaishnavism and surrender to the Divine. At the same time, the concept of oneness of the soul and the Divine was in accordance with the Hindu Advaita philosophy. The most successful blending of the Indo-Aryan Sanatana-Dharma and the Arabic-Persian Islamic mysticism is a peculiarly Indian product that germinated and flowered in undivided Punjab. Also, there is a satisfying congruence between Sikh and Sufi perspectives.

Sheikh Farid-ud-Din Ganj-i-Shakr [1173-1265]

A pre-eminent exponent of Sufism in India was Sheikh Farid [1173-1265]. It is said that Baba Farid, as a young boy, was taught prayers by his mother. When the young lad asked her what would be gained from prayers, she replied that he would get sugar cubes every time he said his prayers. The sugar cubes were hidden under the prayer carpet and given to the lad every times he finished his prayers. One day, when Bibi Miriam forgot to put the sugar cubes in place, much to her surprise, there were cubes beneath the carpet after prayers. Bibi Mariam started calling her son Shakar Ganj, or, the treasury of sugar.

Shaikh Farid-ud-Din Ganj-i-Shakr, popularly known as Baba Farid played an important role in transforming the religious, linguistic and cultural ethos of the land.

Guru Nanak

Two centuries later Guru Nanak was born when a new composite culture and vitally transformed language had evolved in the soil.

In Sikh religious history, Sufism had an important role to play. The compilation of the Guru Granth Sahib is the core event of Punjabi literary and religious history. The best compilation of Nirguna Bhagats like Baba Farid and Namdev are contained in it. Guru Nanak, who was born in April, 1469( i.e. 204 years after the death of Baba Farid), had gone to Ajodhan to meet Shaikh Brahm or Shaikh Farid Sani, who was in the line of succession of the Faridi order of Chishti Silsilah to collect hymns of Baba Farid, which were later on incorporated in the Guru Granth Sahib by Guru Arjan Dev in 1604. Baba Farid laid emphasis on human values and tolerance.

During Baba Farid's time and thereafter there were cordial relations between Hindus and Muslims. Guru Nanak's message was like that of the Sufis in as far as it was meant both for Hindus and Muslims.

The oneness of God

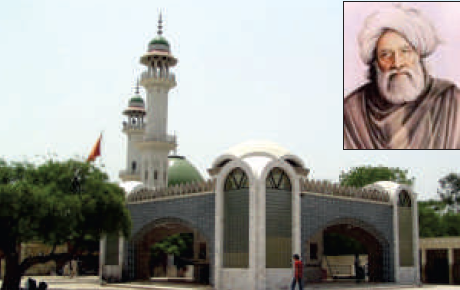

Mystic prose propagating the oneness of God and love of humanity has flowed from the Baani of the Sikh Gurus and the Qalaams of the Sufi saints like Mian Mir, Baba Fareed Ganjshakar, Baba Bulleh Shah, Hazrat Shah Hussein and Sultan Bahu. The mystical songs of these seers, in particular, are the pride of the whole of Punjab and form a common and invaluable heritage for humanity.

Their Sufi kalaams and poetry are a pleasure to read and to relish the beauty of the Punjabi language. Punjabi Sufi poets have used characters and situations from the love legends 'Heer -Ranjha, Mirza -Sahiban, Sohni-Mahiwal, Sassi-Pannu etc to make, amongst others, two of their central points: The love of humankind (and god) and rebellion against the established social and religious norms.

Qissa poetry

(Qissa== story or anecdote)

'Qissa poetry', the ballad poems of Islamic- Punjabi, became popular among both Sufi storytellers and the Gurmukhi musicians, who believed in “ishq” (love) both in life and in commune with God. Thus Heer's longing for Dhido Ranjha becomes an allegory for the sufi's yearning to be united with 'God'. In this verse that has become immensely popular, Bulleh Shah expresses his yearning for the union with the Almighty.

Ranjha Ranjha

Ranjha ranjha kardi hun main aape Ranjha hoyi

Saddo mainoon Dheedo Ranjha, Heer naa akho koyi

Ranjha main wich, main Ranjhe wich, ghair khayyal na koyi

Main naheen au aap hai, apni aap kare diljoyi

Jo kuch saade andar wasse, zaat assadi soyi

Jis de naal main neoonh lagaya oho jaisi hoyi

Chitti chaadar laa sut kuriye, pehan faqeeran loyi

Chitti chaadar daag lagesi, loyii daag na koyi

Taqt hazaare lai chal Bulleah, siyaaleen mile na dhoyi

Ranjha ranjha kardi hun main aape Ranjha hoyi

Remembering Ranjha day and night,

I've become Ranjha myself.

Call me Dhido Ranjha,

No more I be addressed as Heer,

I abuse Ranjha but adore him in my heart.

Ranjha and Heer are a single soul,

No one could ever set them apart

Sheikh Farid-ud-din, was the first Sufi poet who "sang of his insatiable hunger for the love of the Lord in works of immortal beauty". In an age marked by great brutality, he brought the touch of humanity and fellow feeling to all. Farid was also the first poet of Punjab and Punjabi who used the symbol of human relationship between wife and husband to express his longings for union with the Divine. The kafis (lyrics) of Shah Husain (1538- 1599), the popular romantic Sufi saint of Lahore added to Sufi poetry its peculiar element of masti (rapture) and introduced enraptured dancing and passionate signing. Hussain was also the first Sufi poet of Punjabi who adopted the popular measure of Kafi to express his mystic ideas. The credit for introducing the element of the popular lovelegends of Punjab (Heer Ranjha and Sohni Mahiwal) to Sufi Verse and utilizing their persons, places, motifs and incidents as images, metaphors and allegories etc. also goes to him.

Although there are several qissakars who have retold the love legends, it is Waris Shah's Hir, Pilu's Mirza versified in the seventeenth century, Hashim Shah's Sassi and Fazal Shah's Soni that are the most popular.

Waris Shah

Waris Shah's version of Heer Ranjha is the most celebrated of the qissas or legends of Punjab. The qissas are in chaste Punjabi and are open-ended. The lover rebels are characterised as the archetypal patterns of Punjabi behaviour' as they reveal most vividly, the ideals of honesty, loyalty, steadfastness and courage. They signify the synthesis of love and suffering for the highest ideals, both spiritual and societal. Such is the popularity of Heer that she finds mention in the poetry of Bhai Gurudas and Guru Gobind Singh. Also, Udham Singh, who killed General O Dwyer in the run up to India's independence from British rule, declared his name as Ram Mohammad Singh to show the unity of all three religions and also took oath on a book of Heer Ranjha written by Waris Shah.

Waris Shah's creativity and his penning his version of Heer came out of intense frustration over the bitter realities of life, the cruelty of the ruling class and the hypocrisy of the clergy. He was derisive of the clergy and presented Ranjha as an embodiment of universal loneliness that resides in every lover's soul. Major poets of Punjab have, been deeply influenced by Sufism.

Non-Muslim mystic poets

Its influence on the non-Muslim mystic poets of the first half of the twentieth century viz. Sant Rein, Sadhu Daya Singh, Paul Singh Arif, Man Singh Kalidas and Kishan Singh Arif is quite evident. Even the poets of the modern period, including Bhai Vir Singh (1872-1957), the father of modern Punjabi literature, have also imbibed its impact.

Sufism in India

Sufism and tolerance

By Kazi Javed

It is commonly believed that sufism could never have flourished without having accepted the philosophy of Wahdatal Wajood as its ideological foundation

There are two types of sufism: i)one is based on the metaphysics of Wahdatul Wajood; ii)while the other is derived from the philosophy of Wahdatul Shahood. These two types are diametrically opposed to each other so far as their socio and cultural implications are concerned.

The first type, which is usually referred to as wajoodi Sufism, teaches tolerance, moderation, peaceful coexistence and humanistic values. This is because its metaphysics implies that there is a unity and oneness in all that exists. The differences, disagreements and divisions among human beings, ideas and all that exists are illusory. They come into being only when we look at things and matters in a limited and biased perspective and fail to see their true reality.

If all differences are illusory, then it clearly means that mutual differences of human beings, creeds and cultures are also superficial,. They are absurd in the ultimate sense. We should sympathise with those who take these differences seriously and not detest them.

The metaphysics of Wahdatul Shahood, on the other hand, insists on differences and accords primacy to them. This metaphysics developed as a reaction to the sociopolitical, cultural and intellectual trends that flowered out as a consequence of mass popularity of Wahdatul Wajood in the 16th century India. Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi, who first presented it as a thought system, was a contemporary of Emperor Jahangir.

The philosophy of Wahdatul Wajood is Indian in its essence and its origin can be traced to Vedanta. This philosophy was adopted in the early stages of Islamic mysticism. It is commonly believed that sufism could never have flourished without having accepted this philosophy as its ideological foundation.

History has preserved the name of a Sindhi scholar, Abu Ali Sindhi, who is considered to be the first one who introduced the sufi intellectuals of the central Muslim world to Wajoodi doctrine. Bayazid Bastami of the 9th century was the first great sufi who took lessons from him in it. Jami quotes him as saying in his Nafahatal, "I learnt the science of annihilation and unitarianism from Abu Ali of Sindh.

A majority of the Indian sufis adopted this philosophy during the Middle Ages. But we must keep in mind that sufis were attracted to this philosophy mostly because it was in line with their own ideas and attitudes.

The first eminent Indian sufi, Syed Ali Hajveri, for example, belonged to a period when the features of Wajoodi philosophy had not become popular and prominent. He settled in Lahore in the early years of the 11th century. His book Kashful Mahjoob still survives and is considered one of the most important books on sufism. The teachings carried therein are notably humanistic and tolerant.

Syed Ali Hajveri preferred a direct and personal relationship between man and God over religion's ritualistic and abstract forms. This preference provided the metaphysical basis of accepting dissent and treating others with tolerance. Here, for example, we can quote Hajveri's opinion about Hajj. In his famous book, Kashful Mhajoob, he supports the idea: "I am surprised at the one who looks for the house of God in the world, but does not experience and witness it in his own heart."

He also had a liking for music and poetry and did not agree with the religious scholars who believed that Islam had no patience for them. His point of view in this regard is very clear: "The one who says that he does not relish a beautiful voice or music and melody is either a liar or a hypocrite or does not have slightest aesthetic sense. Lack of taste makes such a person even worse than animals and cattle."

Syed Ali Hajveri laid the foundation of Muslim tolerance in the medieval India through his flexible system of thought. Sufis and saints promoted these values in the subsequent centuries. Some of the rulers also adopted this policy of tolerance and tried to create harmony among diverse religious communities in India. In this way, they managed to counter the oppression of what we now term as fundamentalism. They not only provided the people with an opportunity to live in a peaceful and congenial environment, but also contributed towards their genuine spiritual and moral grooming. This state of a affairs made Thomas Arnold to observe: "During the Muslim rule, on the whole, the level of tolerance exhibited towards nonMuslims was missing in Europe till modern times."

It were the sufis of the Chishtia Silsila, or school of thought, who appeared on the Indian scene after Syed Ali Hajveri. This silsila was introduced in our region by Khawaja Moeenud Din who came here from his native town of Seistan during the reign of Prithvi Raj. The sufis of this silsila further promoted religious liberalism, tolerance, interaction and humanistic values that were upheld by Syed Ali Hajveri. Khawaja Moeenud Din used to say: "God has created the humans and the universe for the sake of love, and loving God implies loving human beings regardless of their religion, class, colour or race. The ultimate goal of religion is selfless love for human beings and their service. The observance of religious law and rituals is not essential as the service of fellow humans."

Khawaja Moeenud Din died in 1235 in Ajmer. It was the time when the town of Nagore was emerging as an important centre of sufi humanism and the culture nourished by the Chishtia intellectuals. This transformation took place because of Hameedud Din Nagori who was a pupil of Khawaja Moeenud Din. He was a poet and a spiritual leader. He made the invaluable contribution of combining the finest elements of Hindu and Muslim civilisations to introduce a harmonised culture based on humanism.

The process of adoption was carried on by Baba Faridud Din Ganj Shakar who became the chief of the Chishtia Silsila after the death of Qutbud Din Bahaktiar Kaki in the fourth decade of the 13th century. He was bitterly criticised by conservative religious scholars for adopting nonMuslim practices. We can take him as the finest personification of tolerant culture created by the sufis who was to greatly influence the great founder of Sikh religion, Baba Nanak. He presented his teaching in the form of mellow and captivating Punjabilanguage poetry the major portion of which has been preserved forever by Baba Nanak in Aad Granth.

The ideas, values and culture promoted by the sufis of the prehal period greatly contributed to the development of the Bhakti movement despite the narrowand harsh polices of many Muslim rulers and aristocracy. The origin, nature and aims of the Bhakti movement have been made very controversial. Anyway, in my humble opinion, we can accept the view that Shankar Achariya and Ramanj of the 10th and 11th centuries revived the ancient Bhakti sensibility in South India. It was a pure Hindu affair. But the need to revive Bhakti and its general popularity in North India of the 14th and 15th centuries was a direct result of the cultural and intellectual influence of sufis. Political influence of Islam also played a role.

In northern parts of India, the Bhakti movement produced a number of such Bhagats who had not only unconsciously but consciously absorbed the Muslim influence. Their concept of Bhakti envisaged uniform love for all humans without discrimination on the basis of colour, caste or creed.

Ramananda was the man who initiated the form of Bhakti we are interested in and which strived for the Hindum unity. The liberal elements of his system of thought later embodied themselves in the form of Bhagat Kabir who was born in 1440. Tulsi Das, Bhagat Kabir and Baba Nanak are by many accounts the most refined personalities created by the Indian civilisation of the Middle Ages. They all are representatives of the Bhakti movement.

It may sound strange but it is a fact of history that the founder of the Mughal dynasty, Zaheerud Din Babar, too had absorbed many teachings of the sufis and bhagats that were in the air at the time when he laid the foundation of the Mughal rule in 1526. He did not get a chance to rule for a long time, but during his rule he rejected the narrowand intolerance of the Lodhis and adopted the policy of religious harmony.The kind of moderate enlightenment emphasized by Babar became the basis of his grandson Akbar's policies.

If now we remember him as Akbar the Great, it is mostly because of his policy of religious tolerance and his respect for all religions. I have no intention here to go into details of his policies or his Din. However, I would only say that his policies and Din would never have come into being without the teachings of sufis and bhagats. In fact, it were their teachings that created a new culture and circumstances that were reflected in the policies and ideas of the great Mughal. The polices of Akbar were unacceptable not only to the orthodox religious scholars but also many other sections of Muslim society. They were offensive to them from the religious point of view. They also feared that the distinction of Muslim and nonMuslim would disappear as a result of these policies, and the Muslim dominance in India would be endangered.

The lords and upper class particularly opposed Akbar. They rightly feared that his policies will ultimately deprive them of their supremacy in society. A large number of those lords and other members of the privileged classes had come from the central Asian region. Their vital interests were at variance with those of the Indian people. So winds of change started to blow.

The most vociferous reaction came from Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi who belonged to the then newly introduced sufi school of Naqshbandia. Sheikh Sirhindi can be labelled the ideologue who laid the foundation of Muslim fundamentalism in the subcontinent. Allama Muhammad Iqbal believed him to be `the greatest reformist of Islamic mysticism'. It is interesting to note that many of the orthodox clerics of his day did not like many of his ideas and came down heavily on him.

The basic claim of Sheikh Ahmed Sirhindi was that the highest spiritual experience is that of Wahdatul Shahood and not that of Wahdatul Wajood. One experiences Wahdatul Shahood al the level of consciousness and its highest form is revelation. Therefore, the mystical experience and its proclamation must be within the limits of religious law. This principle enabled the sheikh to defeat the forces of harmony, tolerance and liberalism on three fronts: first the philosophy of Wahdatul Wajood, on which the foundation of Muslim tolerance and enlightenment in India rested, was declared imperfect; second, no room was left for the fraternal Sufism; and third, Ijtehad, which was defined by Allama Iqbal as the principle of movement in Islam, was rendered impracticable. In this way, the future course of the socio-cultural and political life of the Muslims of this region was determined. It ultimately led to the events that took place in our corner of the globe in 1947.

Sufism in India II

Sufis then, Terror now

Reviewed by Shafqat Tanvir Mirza

Dr Fatima Hussain is a teacher of history at the Delhi University and is married to Pakistani writer and chief of the World Punjabi Congres, Fakhar Zaman. The book ‘is an outcome of the proceedings of a seminar’ at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

The contemporary relevance of the Sufis and Bhakti movements is linked with the popularity of Maulana Rumi’s Masnavi in the West and the UNESCO had declared 2007 as the year of Rumi.

The opening paper in the book, ‘Sufism and Bhakti Movements as part of great Indian culture — with special reference to Kashmir’, has been contributed by the Maharaja of Kashmir and member of the Indian parliament, Dr Karan Singh. He says: ‘In Kashmir there have been great religious movements. In medieval times, the interaction between Shaiva Movement of which Yogani Laleshweari, perhaps, was the most glowing figure and Sufi movement at the hands of Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani (Rishi) whose mazaar is at Chrar Sharif and the others was the most extraordinary story of the era.’

The people of Kashmir and followers of Yogani and Nooruddin Rishi are still suffering and demanding their fundamental rights. In fact the current times are similar to the ones that had inspired another Sufi poet of Jammu Kashmir, Mian Muhammad Bukhsh, to address a letter in verse to the then Maharaja, the great-grandfather of Dr Karan Singh:

Raja! Be not proud of your rule. You will not rule forever. You’ll extract gains of tyranny for a few days. Soon you will flee away. Listen! Heed the pleas of the poor! And show no arrogance

Such lines are a common refrain of the genuine Sufis and Bhagats of the Bhakti movement — from Moeenuddin Ajmeri and Baba Farid to Bhagat Kabeer, Baba Nanak, and Nizamuddin Aulia.

The Sufis and the Bhagats stood for the fundamental rights of the people and against the usurpers of such rights. Rights cannot be classified into religious terms. This is why Sufis like Moeenuddin Ajmeri and Baba Farid refused to approve the repression let loose by Muslim rulers. Some Sufis like Shah Inayat (Sindh) and Baba Wajeed of Jullundher took up arms against the tyranny of Muslim rulers.

The Sufis and the Bhagats stood for the fundamental rights of the people and against the usurpers of such rights. This is why Sufis like Moeenuddin Ajmeri and Baba Farid refused to approve the repression let loose by Muslim rulers.

Sufis all over the subcontinent won the hearts of people belonging to the lower classes. Those who embraced the faith of the Sufis in most of the cases were considered Ijlaf (astraps in Bengali) including the peasants, labourers and artisans. Muslim and Hindu aristocrats who were called the Ashraf, had by their side religious leaders known as maulanas and pandits who were forever ready to extend support to the rulers for their anti-people acts. The best example is that of Maulana Abdullah Sultanpuri who served Humayun, Sher Shah Suri, his four successors, and finally Akbar who decided to get rid of him — by sending him for Haj. It was Abdullah Sultanpuri who had decided to get Shah Husain, a prominent poet of Lahore, declared as an infidel.

Abdullah Sultanpuri was also responsible for the persecution of many prominent Sufis of the subcontinent because they all stood for the preservation of the rights of the people at large irrespective of their faith, colour and race.

Sufis and Bhagats preached the universal human values, lived with the common people, spoke in their languages and almost disowned the official or court languages of those periods. So much so that a Bengali Sufi poet of 16th century, Muttalib, was forced to disown his translation of a Muslim religious book in Bengali. In his book titled Language and Politics in Pakistan Dr Tariq Rahman, quotes this Bengali verse:

Muchalmani sastra kstha Bangala Karilum Bahu paap haila niscae janilum.

(I translated Muslim religious books in Bengali. I am sure I committed a great sin)

Sufis and Bhagats stood for the fundamental rights of the people and the nations much before the Charter of Fundamental Rights was approved by the United Nations, to be frequently violated by the super powers. What relevance does Sufism and Bhakti movements have to the current turmoil? This is not discussed in this book which could have done with a better job by the proof-reader to enhance the impact of some very scholarly articles.

The major contributors of this book are Dr Madhu Trivedi, Dr Chander Shekhar, Dr Fehmida Hussain, Prof Harbans Mukhia, Prof Jigar Muhammad, Prof Khwaja Masud, Dr M.D Thomas, Dr Paul Jackson and Zaman Azurda from Kashmir University.

They have dealt with issues mainly in the historical perspective and none of them offer an explanation as to how the lands of Sufis and Bhagats — Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and the South Asia — are not following the concept of live and let live according to the philosophy of the Sufis and the Bhagats. Or why has terrorism been let loose in the land of the Sufis.

Sufism and Bhakti Movement: Contemporary relevance

Edited by Dr Fatima Hussain

Publishers Classic, Lahore

352pp. Rs600