Dara Shukoh

(→Briefly) |

(→His cenotaph) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

Singh also referred to Sir Jadunath Sarkar’s monumental work, A History of Aurangzib, to say Emperor Aurangzeb had, on September 5, 1669, ordered repairs to Dara’s tomb, placing of a chaddar over it and appointment of caretakers. Gandhi said, “News reports from Alamgir's court suggest that Dara's grave had a visible tombstone covered with a shroud. Even so, it is difficult to use the ornate, literary text of chronicles to identify the exact location of the grave. There is a history of misreading rhetorical statements in chronicles such as Amal-i Salih as literal descriptions of Dara Shukoh’s burial place.” | Singh also referred to Sir Jadunath Sarkar’s monumental work, A History of Aurangzib, to say Emperor Aurangzeb had, on September 5, 1669, ordered repairs to Dara’s tomb, placing of a chaddar over it and appointment of caretakers. Gandhi said, “News reports from Alamgir's court suggest that Dara's grave had a visible tombstone covered with a shroud. Even so, it is difficult to use the ornate, literary text of chronicles to identify the exact location of the grave. There is a history of misreading rhetorical statements in chronicles such as Amal-i Salih as literal descriptions of Dara Shukoh’s burial place.” | ||

| + | |||

While adding that 20th century local tradition held Dara's tombstone to be on the terrace of Humayun’s tomb, she asserted, “It’s not, however, the one with the cleft stone that is today popularly associated with the prince.” | While adding that 20th century local tradition held Dara's tombstone to be on the terrace of Humayun’s tomb, she asserted, “It’s not, however, the one with the cleft stone that is today popularly associated with the prince.” | ||

Rezavi said historical sources had to be read with caution. “It is for a reason that historians have maintained it’s not possible to identify the grave on the basis of literary evidence. This latest research is conjecture. That’s fine, but as a historian I am sceptical.” | Rezavi said historical sources had to be read with caution. “It is for a reason that historians have maintained it’s not possible to identify the grave on the basis of literary evidence. This latest research is conjecture. That’s fine, but as a historian I am sceptical.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Supriya Gandhi’s revisionist view= | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL/2019/09/25&entity=Ar01810&sk=F2E5505E&mode=text Manimugdha S Sharma, Sep 25, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Dara Shukoh was neither liberal nor secular: Historian ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mughal prince Dara Shukoh is forever romanticised as a liberal icon who could have altered the fortunes of the Mughal Empire, but who had a tragic end at the hands of his bigoted brother Aurangzeb. There is now renewed interest in him with Aligarh Muslim University proposing to institute a Dara Shukoh Chair, and the R S S extolling him as the ideal Muslim for Indian Muslims to emulate. Yale historian Supriya Gandhi, who has authored a biography titled The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India, speaks to Manimugdha S Sharma about the man and the myth | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Today in India, Dara Shukoh is being held up as a model Muslim while Aurangzeb is denounced as a ‘bad Muslim’. What is your reading of this? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is no point in holding up historical figures as models to be glorified, while vilifying others to be hated and not seeking to understand their contexts. Whether or not Dara Shukoh should have been emperor, whether or not Aurangzeb was a bigot, ought to have absolutely no bearing on how the state treats Indian Muslims today. But we should critically examine these figures and many others. What we need instead is more intellectual freedom — the freedom to read and think critically, in our families, schools, colleges, and public sphere. We need many more public libraries and bookshops. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Dara has this stereotypical image of being a ‘liberal’, ‘secular’ prince who was supposedly better suited to be emperor. What is your assessment? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dara Shukoh was neither liberal nor secular. Those concepts didn’t exist during his time. He lived in an age where it was impossible to even imagine a world without a powerful emperor. A kingdom’s wellbeing was thought to depend on having a strong and just ruler. For Dara, this meant that he modelled himself on past philosopher kings like his own great-grandfather Akbar, though he had his own take on how to do so and didn’t acknowledge their influence. Like other Mughals, such as Akbar and Jahangir, Dara chose to explore the monotheistic currents of Hindu religious thought, for example Vedanta. He was curious and intellectually generous. But his intellectual exercises were aimed at promoting his own spiritual awakening through which he could be the ultimate philosopher-king. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Why do you call Dara Shukoh “the emperor who never was” in your book? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | My book title plays on the counterfactual that people often like to pose — what if Dara Shukoh had actually managed to rule Hindustan? Would the Mughal empire have declined so precipitously, setting off the chain of events that culminated in the subcontinent’s fractured present? But the title also features an important strand of my argument in the book. In modern times, Dara is often viewed as a naive mystic with his head in the clouds, unfit to rule. However, as my book shows, though Dara was passionately committed to his spiritual development, this was always with an eye to his future position as the ruler of Hindustan. We can get a glimpse of how he might have acted as an emperor through the years when he was based in Shahjahanabad from 1654 until his father’s illness in 1657. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Is it true that Dara thought the Upanishads were the hidden books that Islamic traditions refer to? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Quran has a series of verses that refer to a ‘hidden book’ or kitab maknun. Now, traditional interpreters of the Quran do not identify kitab maknun as a literal, tangible book. In contrast, Dara Shukoh declares in the Sirr-i-akbar that the Upanishads are indeed this kitab maknun. Part of his justification rests on the connotation of ‘Upanishad’ as ‘secret’ wisdom. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Biography|S DARA SHUKOHDARA SHUKOH | ||

| + | DARA SHUKOH]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|S DARA SHUKOHDARA SHUKOH | ||

| + | DARA SHUKOH]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|S DARA SHUKOHDARA SHUKOH | ||

| + | DARA SHUKOH]] | ||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

Latest revision as of 18:31, 19 May 2021

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Briefly

Born on March 11, 1615, in Ajmer, the first son of Emperor Shah Jahan, he was known for his translation of the Bhagwad Gita and for books such as Majma-ul-Bahrain, or The Confluence of the Two Seas. He would have ascended the throne, but a battle for succession broke out, pitting him against his younger brothers, Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh.

After Dara Shikoh, the Vali-ahad or heir apparent to the Mughal throne, was defeated by his brother, Aurangzeb, in the battle of Deorai in 1659, he was on the run for several months before being captured and executed in Delhi in September that year. The scholarprince was buried in an unmarked grave in the Humayun’s Tomb complex. That significant spot in Mughal history may at long last have been identified.

After his loss, according to accounts by Francois Bernier, the prince’s personal physician, Shikoh was paraded through the streets of Shahjahanabad atop a filthy elephant before being executed.

Given the circumstances, it isn’t surprising that Shikoh wasn’t given a ceremonial funeral. In fact, he was interred in an unknown spot in the Humayun’s Tomb complex. Supriya Gandhi, in her book The Emperor Who Never Was, writes, “The sources are unanimous in saying that Shikoh was buried in Humayun's magnificent red sandstone tomb. But he was neither conferred the dignity of a ceremonial washing and burial rites nor granted a marked grave. No inscription identifies his gravestone.” She and most historians agree there is no consensus on the precise location of his burial. (See more below)

[edit] Role in history

Ziya us Salam, May 31, 2016: The Hindu

Who is Dara Shukoh?

HIs famous work "Majma-ul-Bahrain" which translates into "The Mingling of Two Oceans" explain his commitment to religious tolerance and hence, Hindu-Muslim unity.

He used to write under the name "Sirr-e-Akbar".

Gopal Gandhi’s Dara Shukoh: A Play raises the relevance of Dara Shikoh in contemporary India

Few men who read history in school remember Dara Shikoh, the philosopher-prince of Mughal India. He is but a fleeting figure even if an enlightened one. The spotlight is well and truly on Aurangzeb, terse, taciturn, untamed. In a world looking for convenient, even if inaccurate, summations, Dara is reduced by our historians to being a favourite son of Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb, a fratricidal ruler who did not hesitate to put to the sword his own. That almost all kings in the years of yore did the same matters little. That Dara had a life before the fatal battle of Samugarh with Aurangzeb, that he had a life quite removed from that of any of his brothers is never pointed out. For most, Aurangzeb is a convenient villain, Dara the easy but fallible hero.

However, today as our nation faces the prospect of being ruled by revisionist politicians — ironically, they seem to be getting mixed up with their history lessons too — it is important to take some time out, and realise what we lost when Dara lost, and what we can gain if we imbibe his spirit. With such a thought, I picked up Gopal Gandhi’s Dara Shukoh: A Play. It was released some time ago and I had all but left it on the shelf with the likes of Dilip Hiro’s Baburnamah for company.

However, the events unfolding in the run-up to the general elections made me go back to it. Dara is relevant, even necessary today. The book instantly set in motion a series of conjectures: what if the heterodox Dara and not the more orthodox Aurangzeb had won the battle of brothers? If mid-17th Century India had thrown up a different victor, would the nation have been partitioned? Didn’t medieval India throw up a man who was wedded to pluralism of thought and faith much before the founding fathers of our Constitution made it a benchmark for future generations? And would Hindus and Muslims have lived here, as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan said, like the two eyes of the nation? Imagine if a Sufi had outlasted a warrior! Imagine.

The questions shall never be answered. But revisit Dara we must. Understand what he stood for, preach many of his things, and we might just end up with a nation that takes pride in its pluralist culture, a society where Hindus read both the Vedas and the Quran, the Muslims appreciate that the concept of one universal God precedes their arrival here; appreciation rather than mere tolerance of each other’s culture being the hallmark. Follow this, and the need to combat the challenge thrown up by communal elements disappears. Who can argue with a man who drinks from the common nectar of Sufis and bhakti saints?

And Gopal Gandhi, with an enviable and apt lineage for such a project, goes about demolishing many prejudices, exposing many lies. He chooses to spell him Shukoh, explaining beautifully that ‘Shikoh’ in Persian means ‘terror’ while ‘Shukoh’ stands for ‘glory’. Gandhi’s Dara is not a tragic figure; rather he is a man whose time is now. Gandhi chooses not to dwell much on a failed general — a poet is doomed to be a failure on a battlefield anyway. He stays focussed on the undercurrents of the thoughts of the man who translated the Upanishads into Persian — ideas that did not endear him to the radical elements on both sides of the religious divide. A play may not necessarily be an ideal substitute for a history textbook.

The best help often comes from the source least expected. A play, a film, a book, a philosopher may yet show us the way. After all, amidst all the political mudslinging and a society being rapidly polarised, we could do worse than heed Dara’s words. Remember what he said when his followers screamed, “Shuja — his brother and fellow claimant to the throne — murdabad”? Dara replied, “Let us not wish death to any one/That is base;/All of us have God’s breath in us,/In any case./We live and have our being/ With his grace.”

[edit] Defeat at Samugarh, 1658

The Times of India, May 28 2016

Murad Ali Baig

Not Plassey 1757 but Samugarh 1658: Fateful tipping point that fixed the subcontinent's future course

On May 29, 1658, India's history changed forever. Aurangzeb's victory over his brother Dara Shikoh marked the beginning of Islamic bigotry in India that not only alienated Hindus but the much more moderate Sufis and Shias as well. Aurangzeb's narrow Sunni beliefs were to make India the hotbed of Muslim fundamentalists, long before the Wahhabis of Saudi Arabia sponsored the fanatics of Taliban and Islamic State. Two great Mughal armies, led by Shah Jahan's eldest son Dara Shikoh and his third son Aurangzeb, clashed on a dusty plain 20 km southeast of Agra.It was not only a battle for the Mughal throne, but a battle for the very soul of India.

It pitted Dara, an eclectic scholar who respected all religions, against Aurangzeb who was an orthodox Sunni Muslim. Dara had translated the Bhagwad Gita and Upanishads from Sanskrit into Persian, to make them known to the public for the first time. The fact that he had been a Sanskrit scholar shows that there had been considerable Hindu-Muslim amity in the time of Shahjahan.

But Dara had been a pampered prince who faced a smaller battle-hardened army that Aurangzeb had marched up from the Deccan, after defeating an Imperial army at Dharmat near Indore. Blocked at the Chambal River, Aurangzeb quietly slipped behind Dara's lines to reach a secret ford across the Chambal by non-stop double marches over two days.

Dara now realised that Aurangzeb's armies had outflanked his army and come very close to Agra, so he had to rush east without most of his cannons.The two armies met on a flat dusty plain east of a village called Samugarh, on an unbelievably hot day with the sun like a furnace in a cloudless sky . There was not enough water so many soldiers and horses collapsed of heat and sun stroke.

The battle was more than just a contest between Dara and his rebel brother. It was becoming a religious war with the Hindus supporting Dara and many Muslim nobles supporting Aurangzeb.

Dara was on the brink of victory when he was betrayed by one of his commanders, Khalilullah Khan. He then retreated to Lahore and then down the Indus. Eventually , he was brought to Delhi and put on trial.

He had written a book called the `Mingling of the Oceans' showing the many similarities between the Quran and the Brahma Shastras. At the trial the imperial Qazi asked Dara to hand him the jade thumb ring that was still on his left hand. He is reported to have turned it over and asked why the green stone was inscribed with the words `Allah' on one side and `Prabhu' on the other.

Dara evidently replied that the creator was known by many names and called God, Allah, Prabhu, Jehova, Ahura Mazda and many more names by devout people in many different lands.He added that it is written in the Quran that Allah had sent down 1,24,000 messengers to show all the people of the world the way of righteousness and he believed that these messengers had been sent not only to Muslims but to all the people of the world in every age. Aurangzeb casually signed the order of execution after the Qazis found Dara guilty of heresy .

Aurangzeb's inflexible religious bigotry made him lose the support of his influential Shia subjects as well as his many Hindu and Rajput followers. By persecuting his own Rajput followers he cut off his arms and weakened his military power.

If Dara had won at Samugarh his rule might have promoted harmony between India's turbulent peoples. A united Mughal empire may have prevented India from becoming so easily colonised by European powers.Samugarh marked the beginning of Islamic bigotry that led over the centuries to the Partition of India, the creation of Pakistan and the backlash of radical Hinduism. Samugarh was a tipping point in India's history.

[edit] His cenotaph

[edit] In Humayun’s Tomb?

From: Manimugdha Sharma, Dara Shukoh’s cenotaph found? Official claims ‘101% certainty’, May 24, 2020: The Times of India

A South Delhi Municipal Corporation official claims to have identified Mughal prince Dara Shukoh’s cenotaph. He has done it independent of the expert committee set up by the central government for precisely this objective. Experts aren’t too sure about Sanjeev Kumar Singh’s “101% certainty” about the find, and all eyes are now on the expert panel.

Singh, an assistant engineer with the municipal corporation, said he was intrigued by the mystery around the final resting place of Dara Shukoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jahan. Historians have maintained that the mortal remains of the prince were interred in an unknown crypt at Humayun’s Tomb, and so his grave is unidentifiable and could be any among the many graves in the lower level of the mausoleum. Some of these graves have open-air cenotaphs on the first-floor terrace.

But after two-and-a-half years of research, Singh thinks otherwise. “I compared the available evidence, but two specifics caught my attention,” he told TOI. “One, a reference in Alamgirnamah saying Prince Dara was buried next to the graves of Prince Daniyal and Prince Murad, Emperor Akbar’s sons, and the second, Emperor Aurangzeb ordering repairs to Dara’s grave, putting a chaddar over it, and appointing caretakers.”

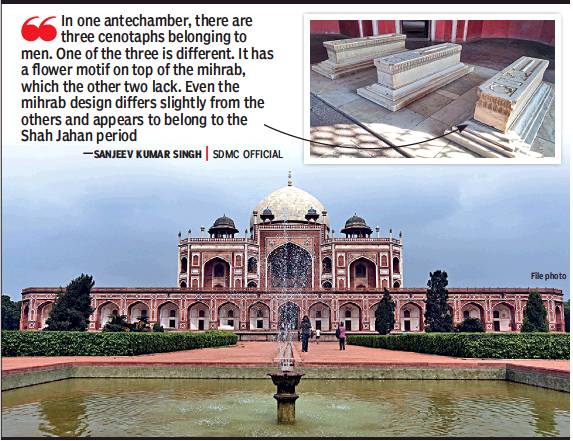

Singh studied the cenotaphs in the antechambers of the Humayun mausoleum. “In one antechamber, there are three cenotaphs belonging to men. One of the three is different. It has a flower motif on top of the mihrab, which the other two lack. Even the mihrab design differs slightly from the others and appears to belong to the Shah Jahan period,” Singh said.

Dr Syed Jamal Hasan, retired Archaeological Survey of India director and member of the central government’s committee to identify Dara’s grave, told TOI that the design might be different but it was difficult to say for certain that the cenotaph belonged to the prince in the absence of any writing on the cenotaph indicating as such. “Because of the Covid lockdown, our committee is yet to visit the tomb crypt to analyse the graves there. Until we go and see it and match it with what the texts say, we cannot say anything,” Dr Hasan said.

And what about the Alamgirnamah? TOI shared the reference cited from it with historians Supriya Gandhi of Yale University and Ali Nadeem Rezavi, former head of history department at Aligarh Muslim University and president of Aligarh Society of History and Archaeology. Both said the passage only said Dara “was buried in the tahkhanaunder the domed structure of the tomb, where Murad and Daniyal are also buried”. Gandhi, who recently wrote Dara Shukoh: The Emperor Who Never Was, relying on Persian sources, said, “Murad and Daniyal are certainly mentioned, but no exact location is identified. Moreover, the reference is to where he is interred, not where his tombstone is.”

Prof Rezavi concurred. “The records only say he was buried in Humayun’s Tomb complex, not exactly where. For Aurangzeb to have a known grave for his brother would have been suicidal because Dara was a Sufi and public knowledge of his tomb would have turned it into a Sufi shrine,” he said.

Singh also referred to Sir Jadunath Sarkar’s monumental work, A History of Aurangzib, to say Emperor Aurangzeb had, on September 5, 1669, ordered repairs to Dara’s tomb, placing of a chaddar over it and appointment of caretakers. Gandhi said, “News reports from Alamgir's court suggest that Dara's grave had a visible tombstone covered with a shroud. Even so, it is difficult to use the ornate, literary text of chronicles to identify the exact location of the grave. There is a history of misreading rhetorical statements in chronicles such as Amal-i Salih as literal descriptions of Dara Shukoh’s burial place.”

While adding that 20th century local tradition held Dara's tombstone to be on the terrace of Humayun’s tomb, she asserted, “It’s not, however, the one with the cleft stone that is today popularly associated with the prince.”

Rezavi said historical sources had to be read with caution. “It is for a reason that historians have maintained it’s not possible to identify the grave on the basis of literary evidence. This latest research is conjecture. That’s fine, but as a historian I am sceptical.”

[edit] Supriya Gandhi’s revisionist view

Manimugdha S Sharma, Sep 25, 2019: The Times of India

Dara Shukoh was neither liberal nor secular: Historian

Mughal prince Dara Shukoh is forever romanticised as a liberal icon who could have altered the fortunes of the Mughal Empire, but who had a tragic end at the hands of his bigoted brother Aurangzeb. There is now renewed interest in him with Aligarh Muslim University proposing to institute a Dara Shukoh Chair, and the R S S extolling him as the ideal Muslim for Indian Muslims to emulate. Yale historian Supriya Gandhi, who has authored a biography titled The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India, speaks to Manimugdha S Sharma about the man and the myth

Today in India, Dara Shukoh is being held up as a model Muslim while Aurangzeb is denounced as a ‘bad Muslim’. What is your reading of this?

There is no point in holding up historical figures as models to be glorified, while vilifying others to be hated and not seeking to understand their contexts. Whether or not Dara Shukoh should have been emperor, whether or not Aurangzeb was a bigot, ought to have absolutely no bearing on how the state treats Indian Muslims today. But we should critically examine these figures and many others. What we need instead is more intellectual freedom — the freedom to read and think critically, in our families, schools, colleges, and public sphere. We need many more public libraries and bookshops.

Dara has this stereotypical image of being a ‘liberal’, ‘secular’ prince who was supposedly better suited to be emperor. What is your assessment?

Dara Shukoh was neither liberal nor secular. Those concepts didn’t exist during his time. He lived in an age where it was impossible to even imagine a world without a powerful emperor. A kingdom’s wellbeing was thought to depend on having a strong and just ruler. For Dara, this meant that he modelled himself on past philosopher kings like his own great-grandfather Akbar, though he had his own take on how to do so and didn’t acknowledge their influence. Like other Mughals, such as Akbar and Jahangir, Dara chose to explore the monotheistic currents of Hindu religious thought, for example Vedanta. He was curious and intellectually generous. But his intellectual exercises were aimed at promoting his own spiritual awakening through which he could be the ultimate philosopher-king.

Why do you call Dara Shukoh “the emperor who never was” in your book?

My book title plays on the counterfactual that people often like to pose — what if Dara Shukoh had actually managed to rule Hindustan? Would the Mughal empire have declined so precipitously, setting off the chain of events that culminated in the subcontinent’s fractured present? But the title also features an important strand of my argument in the book. In modern times, Dara is often viewed as a naive mystic with his head in the clouds, unfit to rule. However, as my book shows, though Dara was passionately committed to his spiritual development, this was always with an eye to his future position as the ruler of Hindustan. We can get a glimpse of how he might have acted as an emperor through the years when he was based in Shahjahanabad from 1654 until his father’s illness in 1657.

Is it true that Dara thought the Upanishads were the hidden books that Islamic traditions refer to?

The Quran has a series of verses that refer to a ‘hidden book’ or kitab maknun. Now, traditional interpreters of the Quran do not identify kitab maknun as a literal, tangible book. In contrast, Dara Shukoh declares in the Sirr-i-akbar that the Upanishads are indeed this kitab maknun. Part of his justification rests on the connotation of ‘Upanishad’ as ‘secret’ wisdom.